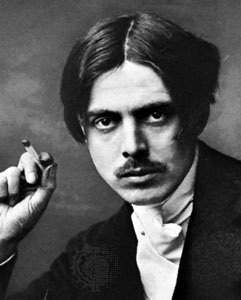

It may be a source of some pride to those of us fated to live out our lives as Americans that the three men who probably had the greatest influence on English literature in our century were all born on this side of the Atlantic. One of them, Wyndham Lewis, to be sure, was born on a yacht anchored in a harbor in Nova Scotia, but his father was an American, served as an officer in the Union Army in the Civil War, and came from a family that has been established here for many generations. The other two were as American in background and education as it is possible to be. Our pride at having produced men of such high achievement should be considered against the fact that all three spent their creative lives in Europe. For Wyndham Lewis the decision was made for him by his mother, who hustled him off to Europe at the age of ten, but he chose to remain in Europe, and to study in Paris rather than to accept the invitation of his father to go to Cornell, and except for an enforced stay in Canada during World War II, spent his life in Europe. The other two, Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot, went to Europe as young men out of college, and it was a part of European, not American, cultural life that they made their contribution to literature. Lewis was a European in training, attitude and point of view, but Pound and Eliot were Americans, and Pound, particularly, remained aggressively American; whether living in London or Italy his interest in American affairs never waned.

The lives and achievements of these three men were closely connected. They met as young men, each was influenced and helped by the other two, and they remained friends, in spite of occasional differences, for the rest of their lives. Many will remember the picture in Time of Pound as a very old man attending the memorial service in Westminster Abbey in 1965 for T.S. Eliot. When Lewis, who had gone blind, was unable to read the proofs of his latest book, it was his old friend, T.S. Eliot who did it for him, and when Pound was confined in St. Elizabeth’s in Washington, Eliot and Lewis always kept in close touch with him, and it was at least partly through Eliot’s influence that he was finally released. The lives and association of these three men, whose careers started almost at the same time shortly before World War I are an integral part of the literary and cultural history of this century.

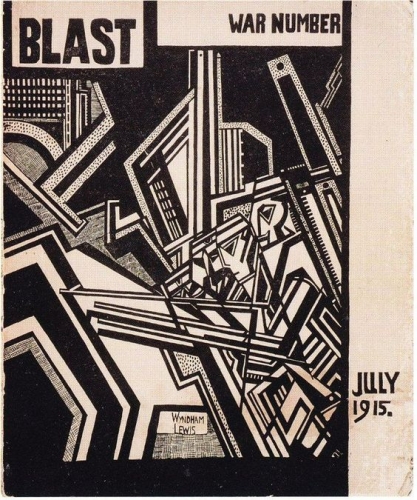

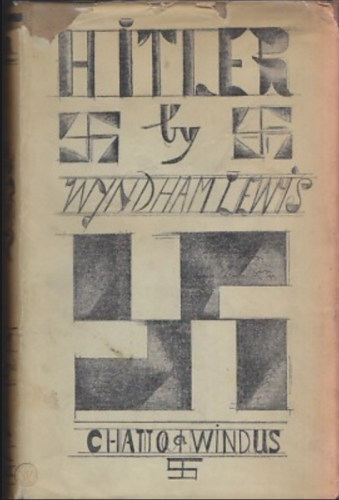

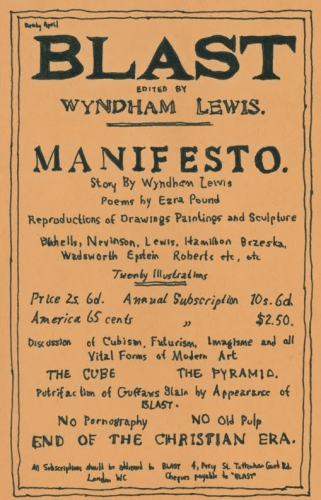

The careers of all three may be said, in a certain way, to have been launched by the publication of Lewis’ magazine Blast. Both Lewis and Pound had been published before and had made something of a name for themselves in artistic and literary circles in London, but it was the publication in June, 1914, of the first issue of Blast that put them, so to speak, in the center of the stage. The first Blast contained 160 pages of text, was well printed on heavy paper, its format large, the typography extravagant, and its cover purple. It contained illustrations, many by Lewis, stories by Rebecca West and Ford Maddox Ford, poetry by Pound and others, but it is chiefly remembered for its “Blasts” and “Blesses” and its manifestos. It was in this first issue of Blast that “vorticism,” the new art form, was announced, the name having been invented by Pound. Vorticism was supposed to express the idea that art should represent the present, at rest, and at the greatest concentration of energy, between past and future. “There is no Present – there is Past and Future, and there is Art,” was a vorticist slogan. English humour and its “first cousin and accomplice, sport” were blasted, as were “sentimental hygienics,” Victorian liberalism, the Royal Academy, the Britannic aesthete; Blesses were reserved for the seafarer, the great ports, for Shakespeare “for his bitter Northern rhetoric of humour” and Swift “for his solemn, bleak wisdom of laughter”; a special bless, as if in anticipation of our hairy age, was granted the hairdresser. Its purpose, Lewis wrote many years later, was to exalt “formality and order, at the expense of the disorderly and the unkempt. It is merely a humorous way,” he went on to say, “of stating the classic standpoint as against the romantic.”

The second, and last, issue of Blast appeared in July, 1915, by which time Lewis was serving in the British army. This issue again contained essays, notes and editorial comments by Lewis and poetry by Pound, but displayed little of the youthful exuberance of the first – the editors and contributors were too much aware of the suicidal bloodletting taking place in the trenches of Flanders and France for that. The second issue, for example, contained, as did the first, a contribution by the gifted young sculptor Gaudier-Brzeska, together with the announcement that he had been killed while serving in the French army.

Between the two issues of Blast, Eliot had arrived in London via Marburg and Oxford, where he had been studying for a degree in philosophy. He met Pound soon after his arrival, and through Pound, Wyndham Lewis. Eliot’s meeting of Pound, who promptly took him under his wing, had two immediate consequences – the publication in Chicago of Prufrock in Harriet Monroe’s Poetry magazine, and the appearance of two other poems a month or two later in Blast. The two issues of Blast established Lewis as a major figure: as a brilliant polemicist and a critic of the basic assumptions and intellectual position of his time, two roles he was never to surrender. Pound had played an important role in Blast, but Lewis was the moving force. Eliot’s role as a contributor of two poems to the second issue was relatively minor, but the enterprise brought them together, and established an association and identified them with a position in the intellectual life of their time which was undoubtedly an important factor in the development and achievement of all three.

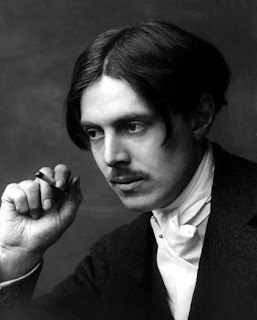

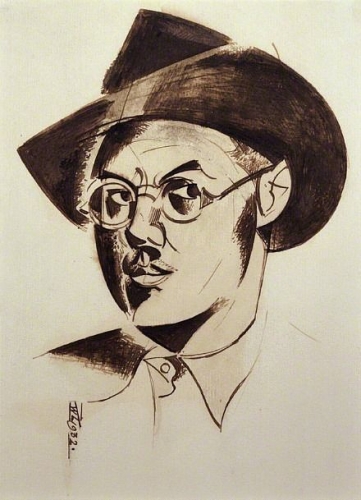

Lewis was born in 1882 on a yacht, as was mentioned before, off the coast of Nova Scotia. Pound was born in 1885 in Hailey, Idaho, and Eliot in 1888 in St. Louis. Lewis was brought up in England by his mother, who had separated from his father, was sent to various schools, the last one Rugby, from which he was dropped, spent several years at an art school in London, the Slade, and then went to the continent, spending most of the time in Paris where he studied art, philosophy under Bergson and others, talked, painted and wrote. He returned to England to stay in 1909. It was in the following year that he first met Ezra Pound, in the Vienna Cafe in London. Pound, he wrote many years later, didn’t greatly appeal to him at first – he seemed overly sure of himself and not a little presumptuous. His first impression, he said, was of “a bombastic galleon, palpably bound to or from, the Spanish Main,” but, he discovered, “beneath its skull and cross-bones, intertwined with fleur de lis and spattered with star-spangled oddities, a heart of gold.” As Lewis became better acquainted with Pound he found, as he wrote many years later, that “this theatrical fellow was one of the best.” And he went on to say, “I still regard him as one of the best, even one of the best poets.”

By the time of this meeting, Lewis was making a name for himself, not only as a writer, but also an artist. He had exhibited in London with some success, and shortly before his meeting with Pound, Ford Maddox Ford had accepted a group of stories for publication in the English Review, stories he had written while still in France in which some of the ideas appeared which he was to develop in the more than forty books that were to follow.

But how did Ezra Pound, this young American poet who was born in Hailey, Idaho, and looked, according to Lewis, like an “acclimatized Buffalo Bill,” happen to be in the Vienna Cafe in London in 1910, and what was he doing there? The influence of Idaho, it must be said at once, was slight, since Pound’s family had taken him at an early age to Philadelphia, where his father was employed as an assayer in the U.S. mint. The family lived first in West Philadelphia, then in Jenkintown, and when Ezra was about six bought a comfortable house in Wyncote, where he grew up. He received good training in private schools, and a considerable proficiency in Latin, which enabled him to enter the University of Pennsylvania shortly before reaching the age of sixteen. It was at this time, he was to write some twenty years later, that he made up his mind to become a poet. He decided at that early age that by the time he was thirty he would know more about poetry than any man living. The poetic “impulse”, he said, came from the gods, but technique was man’s responsibility, and he was determined to master it. After two years at Pennsylvania, he transferred to Hamilton, from which he graduated with a Ph.B. two years later. His college years, in spite of his assertions to the contrary, must have been stimulating and developing – he received excellent training in languages, read widely and well, made some friends, including William Carlos Williams, and wrote poetry. After Hamilton he went back to Pennsylvania to do graduate work, where he studied Spanish literature, Old French, Provencal, and Italian. He was granted an M.A. by Pennsylvania in 1906 and a Fellowship in Romantics, which gave him enough money for a summer in Europe, part of which he spent studying in the British museum and part in Spain. The Prado made an especially strong impression on him – thirty years later he could still describe the pictures in the main gallery and recall the exact order in which they were hung. He left the University of Pennsylvania in 1907, gave up the idea of a doctorate, and after one semester teaching at Wabash College in Crawfordsville, Indiana, went to Europe, to return to his native land only for longer or shorter visits, except for the thirteen years he was confined in St. Elizabeth’s in Washington.

Pound’s short stay at Wabash College was something of a disaster – he found Crawfordsville, Indiana, confining and dull, and Crawfordsville, in 1907, found it difficult to adjust itself to a Professor of Romance Languages who wore a black velvet jacket, a soft-collared shirt, flowing bow tie, patent leather pumps, carried a malacca cane, and drank rum in his tea. The crisis came when he allowed a stranded chorus girl he had found in a snow storm to sleep in his room. It was all quite innocent, he insisted, but Wabash didn’t care for his “bohemian ways,” as the President put it, and was glad for the excuse to be rid of him. He wrote some good poetry while at Wabash and made some friends, but was not sorry to leave, and was soon on his way to Europe, arriving in Venice, which he had visited before, with just eighty dollars.

While in Venice he arranged to have a group of his poems printed under the title A Lume Spento. This was in his preparation for his assault on London, since he believed, quite correctly, that a poet would make more of an impression with a printed book of his poetry under his arm than some pages of an unpublished manuscript. He stayed long enough in Venice to recover from the disaster of Wabash and to gather strength and inspiration for the next step, London, where he arrived with nothing more than confidence in himself, three pounds, and the copies of his book of poems. He soon arranged to give a series of lectures at the Polytechnic on the Literature of Southern Europe, which gave him a little money, and to have the Evening Standard review his book of poetry, the review ending with the sentence, “The unseizable magic of poetry is in this queer paper volume, and words are no good in describing it.” He managed to induce Elkin Mathews to publish another small collection, the first printing of which was one hundred copies and soon sold out, then a larger collection, Personae, the Polytechnic engaged him for a more ambitious series of lectures, and he began to meet people in literary circles, including T.E. Hulme, John Butler Yeats, and Ford Maddox Ford, who published his “Ballad of the Goodley Fere” in the English Review. His book on medieval Latin poetry, The Spirit of Romance, which is still in print, was published by Dent in 1910. The Introduction to this book contains the characteristic line, “The history of an art is the history of masterworks, not of failures or of mediocrity.” By the time the first meeting with Wyndham Lewis took place in the Vienna Cafe, then, which was only two years after Pound’s rather inauspicious arrival in London, he was, at the age of 26, known to some as a poet and had become a man of some standing.

It was Pound, the discoverer of talent, the literary impresario, as I have said, who brought Eliot and Lewis together. Eliot’s path to London was as circuitous as Pound’s, but, as one might expect, less dramatic. Instead of Crawfordsville, Indiana, Eliot had spent a year at the Sorbonne after a year of graduate work at Harvard, and was studying philosophy at the University of Marburg with the intention of obtaining a Harvard Ph.D. and becoming a professor, as one of his teachers at Harvard, Josiah Royce, had encouraged him to do, but the war intervened, and he went to Oxford. Conrad Aiken, one of his closest friends at Harvard, had tried earlier, unsuccessfully, to place several of Eliot’s poems with an English publisher, had met Pound, and had given Eliot a latter of introduction to him. The result of that first meeting with Pound are well known – Pound wrote instantly to Harriet Monroe in Chicago, for whose new magazine, Poetry, he had more or less been made European editor, as follows: “An American called Eliot called this P.M. I think he has some sense tho’ he has not yet sent me any verse.” A few weeks later Eliot, while still at Oxford, sent him the manuscript of The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. Pound was ecstatic, and immediately transmitted his enthusiasm to Miss Monroe. It was he said, “the best poem I have yet had or seen from an American. Pray God it be not a single and unique success.” Eliot, Pound went on to say, was “the only American I know of who has made an adequate preparation for writing. He has actually trained himself and modernized himself on his own.” Pound sent Prufrock to Miss Monroe in October, 1914, with the words, “The most interesting contribution I’ve had from an American. P.S. Hope you’ll get it in soon.” Miss Monroe had her own ideas – Prufrock was not the sort of poetry she thought young Americans should be writing; she much preferred Vachel Lindsey, whose The Firemen’s Ball she had published in the June issue. Pound, however, was not to be put off; letter followed importuning letter, until she finally surrendered and in the June, 1915, issue of Poetry, now a collector’s item of considerable value, the poem appeared which begins:

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherized upon a table …

It was not, needless to say, to be the “single and unique success” Pound had feared, but the beginning of one of the great literary careers of this century. The following month the two poems appeared in Blast. Eliot had written little or nothing for almost three years. The warm approval and stimulation of Pound plus, no doubt, the prospect of publication, encouraged him to go on. In October Poetry published three more new poems, and later in the year Pound arranged to have Elkin Matthews, who had published his two books of poetry to bring out a collection which he edited and called The Catholic Anthology which contained the poems that had appeared in Poetry and one of the two from Blast. The principal reason for the whole anthology, Pound remarked, “was to get sixteen pages of Eliot printed in England.”

If all had gone according to plan and his family’s wishes, Eliot would have returned to Harvard, obtained his Ph.D., and become a professor. He did finish his thesis – “To please his parents,” according to his second wife, Valerie Eliot, but dreaded the prospect of a return to Harvard. It didn’t require much encouragement from Pound, therefore, to induce him to stay in England – it was Pound, according to his biographer Noel Stock “who saved Eliot for poetry.” Eliot left Oxford at the end of the term in June, 1915, having in the meantime married Vivien Haigh-Wood. That Fall he took a job as a teacher in a boy’s school at a salary of £140 a year, with dinner. He supplemented his salary by book reviewing and occasional lectures, but it was an unproductive, difficult period for him, his financial problems increased by the illness of his wife. After two years of teaching he took a position in a branch of Lloyd’s bank in London, hoping that this would give him sufficient income to live on, some leisure for poetry, and a pension for his wife should she outlive him. Pound at this period fared better than Eliot – he wrote music criticism for a magazine, had some income from other writing and editorial projects, which was supplemented by the small income of his wife, Dorothy Shakespear and occasional checks from his father. He also enjoyed a more robust constitution that Eliot, who eventually broke down under the strain and was forced, in 1921, to take a rest cure in Switzerland. It was during this three-month stay in Switzerland that he finished the first draft of The Waste Land, which he immediately brought to Pound. Two years before, Pound had taken Eliot on a walking tour in France to restore his health, and besides getting Eliot published, was trying to raise a fund to give him a regular source of income, a project he called “Bel Esprit.” In a latter to John Quinn, the New York lawyer who used his money, perceptive critical judgment and influence to help writers and artists, Pound, referring to Eliot, wrote, “It is a crime against literature to let him waste eight hours vitality per diem in that bank.” Quinn agreed to subscribe to the fund, but it became a source of embarrassment to Eliot who put a stop to it.

The Waste Land marked the high point of Eliot’s literary collaboration with Pound. By the time Eliot had brought him the first draft of the poem, Pound was living in Paris, having left London, he said, because “the decay of the British Empire was too depressing a spectacle to witness at close range.” Pound made numerous suggestions for changes, consisting largely of cuts and rearrangements. In a latter to Eliot explaining one deletion he wrote, “That is 19 pages, and let us say the longest poem in the English langwidge. Don’t try to bust all records by prolonging it three pages further.” A recent critic described the processes as one of pulling “a masterpiece out of a grabbag of brilliant material”; Pound himself described his participation as a “Caesarian operation.” However described, Eliot was profoundly grateful, and made no secret of Pound’s help. In his characteristically generous way, Eliot gave the original manuscript to Quinn, both as a token for the encouragement Quinn had given to him, and for the further reason, as he put it in a letter to Quinn, “that this manuscript is worth preserving in its present form solely for the reason that it is the only evidence of the difference which his [Pound’s] criticism has made to the poem.” For years the manuscript was thought to have been lost, but it was recently found among Quinn’s papers which the New York Public Library acquired some years after his death, and now available in a facsimile edition.

The first publication of The Waste Land was in the first issue of Eliot’s magazine Criterion, October, 1922. The following month it appeared in New York in The Dial. Quinn arranged for its publication in book form by Boni and Liveright, who brought it out in November. The first printing of one thousand was soon sold out, and Eliot was given the Dial award of the two thousand dollars. Many were puzzled by The Waste Land, one reviewer even thought that Mr. Eliot might be putting over a hoax, but Pound was not alone in recognizing that in his ability to capture the essence of the human condition in the circumstances of the time, Eliot had shown himself, in The Waste Land, to be a poet. To say that the poem is merely a reflection of Eliot’s unhappy first marriage, his financial worries and nervous breakdown is far too superficial. The poem is a reflection, not of Eliot, but of the aimlessness, disjointedness, sordidness of contemporary life. In itself, it is in no way sick or decadent; it is a wonderfully evocative picture of the situation of man in the world as it is. Another poet, Kathleen Raine, writing many years after the first publication of The Waste Land on the meaning of Eliot’s early poetry to her generation, said it

…enabled us to know our generation imaginatively. All those who have lived in the Waste Land of London can, I suppose, remember the particular occasion on which, reading T.S. Eliot’s poems for the first time, an experience of the contemporary world that had been nameless and formless received its apotheosis.

Eliot sent one of the first copies he received of the Boni and Liveright edition to Ezra Pound with the inscription “for E.P. miglior fabbro from T.S.E. Jan. 1923.” His first volume of collected poetry was dedicated to Pound with the same inscription, which came from Dante and means, “the better marker.” Explaining this dedication Eliot wrote in 1938:

I wished at that moment to honour the technical mastery and critical ability manifest in [Pound’s] . . . work, which had also done so much to turn The Waste Land from a jumble of good and bad passages into a poem.

Pound and Eliot remained in touch with each other – Pound contributed frequently to the Criterion, and Eliot, through his position at Faber and Faber, saw many of Pounds’ books through publication and himself selected and edited a collection of Pound’s poetry, but there was never again that close collaboration which had characterized their association from their first meeting in London in 1914 to the publication of The Waste Land in the form given it by Pound in 1922.

As has already been mentioned, Pound left London in 1920 to go to Paris, where he stayed on until about 1924 – long enough for him to meet many people and for the force of his personality to make itself felt. He and his wife were frequent visitors to the famous bookshop, Shakespeare and Co. run by the young American Sylvia Beach, where Pound, among other things, made shelves, mended chairs, etc.; he also was active gathering subscriptions for James Joyces’ Ulysses when Miss Beach took over its publication. The following description by Wyndham Lewis of an encounter with Pound during the latter’s Paris days is worth repeating. Getting no answer after ringing the bell of Pound’s flat, Lewis walked in and discovered the following scene:

A splendidly built young man, stripped to the waist, and with a torso of dazzling white, was standing not far from me. He was tall, handsome and serene, and was repelling with his boxing gloves – I thought without undue exertion – a hectic assault of Ezra’s. After a final swing at the dazzling solar plexus (parried effortlessly by the trousered statue) Pound fell back upon the settee. The young man was Hemingway.

Pound, as is well known, took Hemingway in hand, went over his manuscripts, cut out superfluous words as was custom, and helped him find a publisher, a service he had performed while still in London for another young American, Robert Frost. In a letter to Pound, written in 1933, Hemingway acknowledged the help Pound had given him by saying that he had learned more about “how to write and how not to write” from him “than from any son of a bitch alive, and he always said so.”

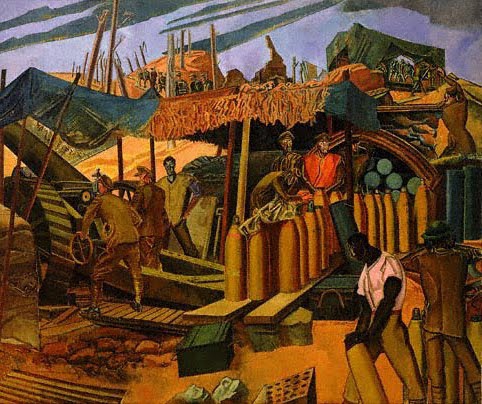

When we last saw Lewis, except for his brief encounter with Pound and Hemingway wearing boxing gloves, he had just brought out the second issues of Blast and gone off to the war to end all war. He served for a time at the front in an artillery unit, and was then transferred to a group of artists who were supposed to devote their time to painting and drawing “the scene of war,” as Lewis put it, a scheme which had been devised by Lord Beaverbrook, through whose intervention Lewis received the assignment. He hurriedly finished a novel, Tarr, which was published during the war, largely as a result of Pound’s intervention, in Harriet Shaw Weaver’s magazine The Egoist, and in book form after the war had ended. It attracted wide attention; Rebecca West, for example, called it “A beautiful and serious work of art that reminds one of Dostoevsky.” By the early twenties, Lewis, as the editor of Blast, the author of Tarr and a recognized artist was an established personality, but he was not then, and never became a part of the literary and artistic establishment, nor did he wish to be.

For the first four years following his return from the war and recovery from a serious illness that followed it little was heard from Lewis. He did bring out two issues of a new magazine, The Tyro, which contained contributions from T.S. Eliot, Herbert Read and himself, and contributed occasionally to the Criterion, but it was a period, for him, of semi-retirement from the scene of battle, which he devoted to perfecting his style as a painter and to study. It was followed by a torrent of creative activity – two important books on politics, The Art of Being Ruled (1926) and The Lion and the Fox (1927), a major philosophical work, Time and Western Man (1927), followed by a collection of stories, The Wild Body (1927) and the first part of a long novel, Childermass (1928). In 1928, he brought out a completely revised edition of his wartime novel Tarr, and if all this were not enough, he contributed occasionally to the Criterion, engaged in numerous controversies, painted and drew. In 1927 he founded another magazine, The Enemy, of which only three issues appeared, the last in 1929. Lewis, of course, was “the Enemy.” He wrote in the first issue:

The names we remember in European literature are those of men who satirised and attacked, rather than petted and fawned upon, their contemporaries. Only this time exacts an uncritical hypnotic sleep of all within it.

One of Lewis’ best and most characteristic books is Time and Western Man; it is in this book that he declared war, so to speak, on what he considered the dominant intellectual position of the twentieth century – the philosophy of time, the school of philosophy, as he described it, for which “time and change are the ultimate realities.” It is the position which regards everything as relative, all reality a function of time. “The Darwinian theory and all the background of nineteenth century thought was already behind it,” Lewis wrote, and further “scientific” confirmation was provided by Einstein’s theory of relativity. It is a position, in Lewis’ opinion, which is essentially romantic, “with all that word conveys in its most florid, unreal, inflated, self-deceiving connotation.”

The ultimate consequence of the time philosophy, Lewis argued, is the degradation of man. With its emphasis on change, man, the man of the present, living man for the philosophy of time ends up as little more than a minute link in the endless process of progressive evolution –lies not in what he is, but in what he as a species, not an individual, may become. As Lewis put it:

You, in imagination, are already cancelled by those who will perfect you in the mechanical time-scale that stretches out, always ascending, before us. What do you do and how you live has no worth in itself. You are an inferior, fatally, to all the future.

Against this rather depressing point of view, which deprives man of all individual worth, Lewis offers the sense of personality, “the most vivid and fundamental sense we possess,” as he describes it. It is this sense that makes man unique; it alone makes creative achievement possible. But the sense of personality, Lewis points out, is essentially one of separation, and to maintain such separation from others requires, he believes, a personal God. As he expressed it: “In our approaches to God, in consequence, we do not need to “magnify” a human body, but only to intensify that consciousness of a separated and transcendent life. So God becomes the supreme symbol of our separation and our limited transcendence….It is, then, because the sense of personality is posited as our greatest “real”, that we require a “God”, a something that is nothing but a person, secure in its absolute egoism, to be the rationale of this sense.”

It is exactly “our separation and our limited transcendence” that the time philosophy denies us; its God is not, in Lewis’ words “a perfection already existing, eternally there, of which we are humble shadows,” but a constantly emerging God, the perfection toward which man is thought to be constantly striving. Appealing as such a conception may on its surface appear to be, this God we supposedly attain by our strenuous efforts turns out to be a mocking God; “brought out into the daylight,” Lewis said, “it would no longer be anything more than a somewhat less idiotic you.”

In Time and Western Man Lewis publicly disassociated himself from Pound, Lewis having gained the erroneous impression, apparently, that Pound had become involved in a literary project of some kind with Gertrude Stein, whom Lewis hated with all the considerable passion of which he was capable. To Lewis, Gertrude Stein, with her “stuttering style” as he called it, was the epitomy of “time philosophy” in action. The following is quoted by Lewis is in another of his books, The Diabolical Principle, and comes from a magazine published in Paris in 1925 by the group around Gertrude Stein; it is quoted here to give the reader some idea of the reasons for Lewis’ strong feelings on the subject of Miss Stein:

If we have a warm feeling for both (the Superrealists) and the Communists, it is because the movements which they represent are aimed at the destruction of a thoroughly rotten structure … We are entertained intellectually, if not physically, with the idea of (the) destruction (of contemporary society). But … our interests are confined to literature and life … It is our purpose purely and simply to amuse ourselves.

The thought that Pound would have associated himself with a group expounding ideas on this level of irresponsibility would be enough to cause Lewis to write him off forever, but it wasn’t true; Pound had met Gertrude Stein once or twice during his stay in Paris, but didn’t get on with her, which isn’t at all surprising. Pound also didn’t particularly like Paris, and in 1924 moved to Rapallo, a small town on the Mediterranean a few miles south of Genoa, where he lived until his arrest by the American authorities at the end of World War II.

In an essay written for Eliot’s sixtieth birthday, Lewis had the following to say about the relationship between Pound and Eliot:

It is not secret that Ezra Pound exercised a very powerful influence upon Mr. Eliot. I do not have to define the nature of this influence, of course. Mr. Eliot was lifted out of his lunar alley-ways and fin de siecle nocturnes, into a massive region of verbal creation in contact with that astonishing didactic intelligence, that is all.

Lewis’ own relationship with Pound was of quite a different sort, but during the period from about 1910 to 1920, when Pound left London, was close, friendly, and doubtless stimulating to both. During Lewis’ service in the army, Pound looked after Lewis’ interests, arranged for the publication of his articles, tried to sell his drawings, they even collaborated in a series of essays, written in the form of letters, but Lewis, who in any case was inordinately suspicious, was quick to resent Pound’s propensity to literary management. After Pound settled in Rapallo they corresponded only occasionally, but in 1938, when Pound was in London, Lewis made a fine portrait of him, which hangs in the Tate Gallery. In spite of their occasional differences and the rather sharp attack on Pound in Time and Western Man, they remained friends, and Lewis’ essay for Eliot’s sixtieth birthday, which was written while Pound was still confined in St. Elizabeth’s, is devoted largely to Pound, to whom Lewis pays the following tribute:

So, for all his queerness at times–ham publicity of self, misreading of part of poet in society–in spite of anything that may be said Ezra is not only himself a great poet, but has been of the most amazing use to other people. Let it not be forgotten for instance that it was he who was responsible for the all-important contact for James Joyce–namely Miss Weaver. It was his critical understanding, his generosity, involved in the detection and appreciation of the literary genius of James Joyce. It was through him that a very considerable sum of money was put at Joyce’s disposal at the critical moment.

Lewis concludes his comments on Pound with the following:

He was a man of letters, in the marrow of his bones and down to the red rooted follicles of his hair. He breathed Letters, ate Letters, dreamt Letters. A very rare kind of man.

Two other encounters during his London period had a lasting influence on Pound’s thought and career–the Oriental scholar Ernest Fenollosa and Major Douglas, the founder of Social Credit. Pound met Douglas in 1918 in the office of The New Age, a magazine edited by Alfred H. Orage, and became an almost instant convert. From that point on usury became an obsession with him, and the word “usurocracy,” which he used to denote a social system based on money and credit, an indispensable part of his vocabulary. Social Credit was doubtless not the panacea Pound considered it to be, but that Major Douglas was entirely a fool seems doubtful too, if the following quotation from him is indicative of the quality of his thought:

I would .. make the suggestion … that the first requisite of a satisfactory governmental system is that it shall divest itself of the idea that it has a mission to improve the morals or direct the philosophy of any of its constituent citizens.

Ernest Fenollosa was a distinguished Oriental scholar of American origin who had spent many years in Japan, studying both Japanese and Chinese literature, and had died in 1908. Pound met his widow in London in 1913, with the result that she entrusted her husband’s papers to him, with her authorization to edit and publish them as he thought best. Pound threw himself into the study of the Fenollosa material with his usual energy, becoming, as a result, an authority on the Japanese Noh drama and a lifelong student of Chinese. He came to feel that the Chinese ideogram, because it was never entirely removed from its origin in the concrete, had certain advantages over the Western alphabet. Two years after receiving the Fenollosa manuscripts, Pound published a translation of Chinese poetry under the title Cathay. The Times Literary Supplement spoke of the language of Pound’s translation as “simple, sharp, precise.” Ford Maddox Ford, in a moment of enthusiasm, called Cathay “the most beautiful book in the language.”

Pound made other translations, from Provencal, Italian, Greek, and besides the book of Chinese poetry, translated Confucius, from which the following is a striking example, and represents a conception of the relationship between the individual and society to which Pound attached great importance, and frequently referred to in his other writing:

The men of old wanting to clarify and diffuse throughout the empire that light which comes from looking straight into the heart and then acting, first set up good government in their own states; wanting good government in their states, they first established order in their own families; wanting order in the home, they first disciplined themselves; desiring self-discipline, they rectified their own hearts; and wanting to rectify their hearts; they sought precise verbal definitions of their inarticulate thoughts; wishing to attain precise verbal definitions, they sought to extend their knowledge to the utmost. This completion of knowledge is rooted in sorting things into organic categories.

When things had been classified in organic categories, knowledge moved toward fulfillment; given the extreme knowable points, the inarticulate thoughts were defined with precision. Having attained this precise verbal definition, they then stabilized their hearts, they disciplined themselves; having attained self-discipline, they set their own houses in order; having order in their own homes, they brought good government to their own states; and when their states were well governed, the empire was brought into equilibrium.

Pound’s major poetic work is, of course, The Cantos, which he worked on over a period of more than thirty years. One section, The Pisan Cantos, comprising 120 pages and eleven cantos, was written while Pound was confined in a U.S. Army detention camp near Pisa, for part of the time in a cage. Pound’s biographer, Noel Stock, himself a poet and a competent critic, speaks of the Pisan Cantos as follows:

They are confused and often fragmentary; and they bear no relation structurally to the seventy earlier cantos; but shot through by a rare sad light they tell of things gone which somehow seem to live on, and are probably his best poetry. In those few desperate months he was forced to return to that point within himself where the human person meets the outside world of real things, and to speak of what he found there. If at times the verse is silly, it is because in himself Pound was often silly; if at times it is firm, dignified and intelligent, it is because in himself Pound was often firm, dignified and intelligent; if it is fragmentary and confused, it is because Pound was never able to think out his position and did not know how the matters with which he dealt were related; and if often lines and passages have a beauty seldom equaled in the poetry of the twentieth century it is because Pound had a true lyric gift.

As for the Cantos as a whole, I am not competent to make even a comment, much less to pass judgment. Instead I will quote the distinguished English critic Sir Herbert Read on the subject:

I am not going to deny that for the most part the Cantos present insuperable difficulties for the impatient reader, but, as Pound says somewhere, “You can’t get through hell in a hurry.” They are of varying length, but they already amount to more than five hundred pages of verse and constitute the longest, and without hesitation I would say the greatest, poetic achievement of our time.

When The Waste Land was published in 1922 Eliot was still working as a clerk in a London bank and had just launched his magazine, The Criterion. He left the bank in 1925 to join the newly organized publishing firm of Faber and Gwyer, later to become Faber and Faber, which gave him the income he needed, leisure for his literary pursuits and work that was congenial and appropriate. One of his tasks at Fabers, it used to be said, was writing jacket blurbs. His patience and helpfulness to young authors was well known–from personal experience I can bear witness to his kindness to inexperienced publishers; his friends, in fact, thought that the time he devoted to young authors he felt had promise might have been better spent on his own work. In spite of the demands on his time and energy, he continued to edit the Criterion, the publication of which was eventually taken over by Faber. He attached the greatest importance to the Criterion, as is evidenced by the following from a letter to Lewis dated January 31, 1925 which is devoted entirely to the Criterion and his wish for Lewis to continue to write regularly for it, “Furthermore I am not an individual but an instrument, and anything I do is in the interest of art and literature and civilization, and is not a matter for personal compensation.” As it worked out, Lewis wrote only occasionally for the Criterion, not at all for every issue as Eliot had proposed in the letter referred to above. The closeness of their association, however, in spite of occasional differences, may be judged not only from Eliot’s wish to have something from Lewis in every issue, but from the following from a letter to Eliot from Lewis:

As I understand with your paper that you are almost in the position I was in with Tyro and Blast I will give you anything I have for nothing, as you did me, and am anxious to be of use to you: for I know that every failure of an exceptional attempt like yours with the Criterion means that the chance of establishing some sort of critical standard here is diminished.

Pound also contributed frequently to the Criterion, but at least pretended not to think much of it–“… a magnificent piece of editing, i.e. for the purpose of getting in to the Athenaeum Club, and becoming permanent,” he remarked on one occasion. He, by the way, accepted some of the blame for what he considered to be Eliot’s unduly cautious approach to criticism. In a letter to the Secretary of the Guggenheim Foundation, written in 1925 to urge them to extend financial assistance to Eliot and Lewis, he made the following comment:

I may in some measure be to blame for the extreme caution of his [Eliot’s] criticism. I pointed out to him in the beginning that there was no use of two of us butting a stone wall; that he’d never be as hefty a battering ram as I was, nor as explosive as Lewis, and that he’d better try a more oceanic and fluid method of sapping the foundations. He is now respected by the Times Lit. Sup. But his criticism no longer arouses my interest.

What Pound, of course, wished to “sap” was not the “foundations”of an ordered society, but of established stupidity and mediocrity. The primary aim of all three, Pound, Eliot and Lewis, each in his own way, was to defend civilized values. For Eliot, the means to restore the health of Western civilization was Christianity. In his essay The Idea of A Christian Society he pointed out the dangers of the dominant liberalism of the time, which he thought “must either proceed into a gradual decline of which we can see no end, or reform itself into a positive shape which is likely to be effectively secular.” To attain, or recover, the Christian society which he thought was the only alternative to a purely secular society, he recommended, among other things, a Christian education. The purpose of such an education would not be merely to make people pious Christians, but primarily, as he put it, “to train people to be able to think in Christian categories.” The great mass of any population, Eliot thought, necessarily occupied in the everyday cares and demands of life, could not be expected to devote much time or effort to “thinking about the objects of faith,” their Christianity must be almost wholly realized in behavior. For Christian values, and the faith which supports them to survive there must be, he thought, a “Community of Christians,” of people who would lead a “Christian life on its highest social level.”

Eliot thought of “the Community of Christians” not as “an organization, but a body of indefinite outline, composed of both clergy and laity, of the more conscious, more spiritually and intellectually developed of both.” It will be their “identity of belief and aspiration, their background of a common culture, which will enable them to influence and be influenced by each other, and collectively to form the conscious mind and the conscience of the nation.” Like William Penn, Eliot didn’t think that the actual form of government was as important as the moral level of the people, for it is the general ethos of the people they have to govern, not their own piety, that determines the behaviour of politicians.” For this reason, he thought, “A nation’s system of education is much more important than its system of government.”

When we consider the very different personalities of these three men, all enormously gifted, but quite different in their individual characteristics–Pound, flamboyant, extravagant; Eliot, restrained, cautious; Lewis, suspicious, belligerent–we can’t help but wonder how it was possible for three such men to remain close friends from the time they met as young men until the ends of their lives. Their common American background no doubt played some part in bringing Pound and Eliot together, and they both shared certain characteristics we like to think of as American: generosity, openness to others, a fresher, more unencumbered attitude toward the past than is usual for a European, who, as Goethe remarked, carries the burden of the quarrels of a long history. But their close association, mutual respect and friendship were based on more than their common origin on this side of the Atlantic. In their basic attitude toward the spirit of their time, all three were outsiders; it was a time dominated by a facile, shallow liberalism, which, as Eliot once remarked, had “re- placed belief in Divine Grace” with “the myth of human goodness.” Above all they were serious men, they were far more interested in finding and expressing the truth than in success as the world understands it. The English critic E. W. F. Tomlin remarked that a characteristic of these three “was that they had mastered their subjects, and were aware of what lay beyond them. The reading that went into Time and Western Man alone exceeded the life-time capacity of many so-called ‘scholars.’” The royalties Lewis earned from this book, one of the most important of our time, which represented an immense amount of work and thought of the highest order, didn’t amount to a pittance, but Lewis’ concern, as he put it toward the end of his life, was for “the threat of extinction to the cultural tradition of the West.” It was this mutual concern, on a very high level, and an utterly serious attitude toward creative work that brought them and held them together.

Why did Pound and Eliot stay in Europe, and what might have happened to them if they had come back to this country, as both were many times urged to do, or to Lewis if he had gone to Cornell and stayed over here? In Pound’s case, the answer is rather simple, and was given in essence by his experience in Crawfordsville, Indiana, as a young man, and the treatment he received following the war. There is no doubt that in making broadcasts on the Italian radio during wartime he was technically guilty of treason; against this, it seems to me, must be weighed the effect of the broadcasts, which was zero, and his achievement as a poet and critic, which is immense. One can’t expect magnanimity from any government, and especially not in the intoxication of victory in a great war and overwhelming world power, but one might have expected the academic and literary community to have protested the brutal treatment meted out to Pound. It didn’t, nor was there any protest of his long confinement in a mental institution except on the part of a few individuals; his release was brought about largely as a result of protests from Europe, in which Eliot played a substantial part. When, however, during his confinement in St. Elizabeth’s, the Bollingen prize for poetry was given him for the Pisan Cantos, the liberal establishment reacted with the sort of roar one might have expected had the Nobel Peace Prize been awarded to Adolf Hitler.

Lewis spent some five years in Toronto during World War II, which, incidentally, provided him with the background for one of his greatest novels, Self Condemned. He was desperately hard up, and tried to get lecture engagements from a number of universities, including the University of Chicago. A small Canadian Catholic college was the only representative of the academic institutions of North America to offer this really great, creative intelligence something more substantial than an occasional lecture. Since his death, Cornell and the University of Buffalo have spent large sums accumulating Lewis material-manuscripts, letters, first editions, drawings, etc. When they could have done something for Lewis himself, to their own glory and profit, they ignored him.

The American intellectual establishment, on the other hand, did not ignore the Communist-apologist Harold Laski, who was afforded all the honors and respect at its command, the Harold Laski who, in 1934, at the height of Stalinism–mass arrests, millions in slave labor camps and all the rest–had lectured at the Soviet Institute of Law.

Following his return to England the Labour government gave Lewis, “the Enemy” of socialism, as he called himself, a civil pension, and the BBC invited him to lecture regularly on modern art and to write for its publication, The Listener. He was even awarded an honorary degree by the University of Leeds. Can anyone imagine CBS, for example, offering a position of any kind to a man with Lewis’ unorthodox views, uncompromising intelligence, and ability to see the world for what it is, the Ford Foundation offering him a grant, or Harvard or Yale granting him an honorary degree? Harold Laski indeed yes, but Wyndham Lewis? It is inconceivable.

The following taken from letters from Ezra Pound, the first written in 1926 to Harriet Monroe, and the second in 1934 to his old professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Felix Schelling, puts the problem of the poet in America as he saw it very graphically:

Poverty here is decent and honourable. In America it lays one open to continuous insult on all sides. . . Re your question is it any better abroad for authors: England gives small pensions; France provides jobs. . . Italy is full of ancient libraries; the jobs are quite comfortable, not very highly paid, but are respectable, and can’t much interfere with the librarians’ time.

As for “expatriated”? You know damn well the country wouldn’t feed me. The simple economic fact that if I had returned to America I shd. have starved, and that to maintain anything like the standard of living, or indeed to live, in America from 1918 onwards I shd. have had to quadruple my earnings, i.e. it wd. have been impossible for me to devote any time to my REAL work.

Eliot, of course, fared much better than Pound at the hands of the academy. As early as 1932 he was invited to give the Charles Eliot Norton lectures at Harvard, many universities honored themselves by awarding him honorary degrees, he was given the Nobel Prize, etc. One can’t help but wonder, however, if his achievement would have been possible if he had completed his Ph.D. and become a Harvard professor. He wrote some of his greatest poetry and founded the Criterion while still a bank clerk in London. One can say with considerable justification that as a clerk in Lloyd’s Bank in London Eliot had more opportunity for creative work and got more done than would have been possible had he been a Harvard professor. It was done, of course, at the cost of intensely hard work–in a letter to Quinn in the early twenties he remarks that he was working such long hours that he didn’t have time either for the barber or the dentist. But he had something to show for it.

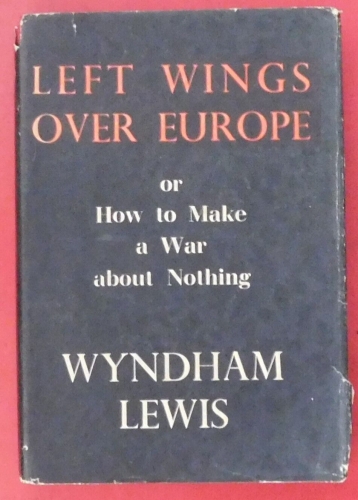

It is impossible, of course, to sum up the achievement of these three men. They were very much a part of the time in which they lived, however much they rejected its basic assumptions and point of view. Both Lewis and Eliot described themselves as classicists, among other reasons, no doubt, because of the importance they attached to order; Lewis at one time called Pound a “revolutionary simpleton,” which in certain ways was probably justified, but in his emphasis on “precise verbal definitions,” on the proper use of language, Pound was a classicist too. All three, each in his own way, were concerned with the health of society; Eliot founded the Criterion to restore values; in such books as Time and Western Man, Paleface, The Art of Being Ruled, Lewis was fighting for an intelligent understanding of the nature of our civilization and of the forces he thought were undermining it. The political books Lewis wrote in the thirties, for which he was violently and unfairly condemned, were written not to promote fascism, as some simple-minded critics have contended, but to point out that a repetition of World War I would be even more catastrophic for civilization than the first. In many of his political judgments Pound was undoubtedly completely mistaken and irresponsible, but he would deserve an honored place in literature only for his unerring critical judgment, for his ability to discern quality, and for his encouragement at a critical point in the career of each of such men as Joyce, Hemingway, Eliot, Frost, and then there are his letters–letters of encouragement and criticism to aspiring poets, to students, letters opening doors or asking for help for a promising writer, the dozens of letters to Harriet Monroe. “Keep on remindin’ ’em that we ain’t bolsheviks, but only the terrifyin’ voice of civilization, kultchuh, refinement, aesthetic perception,” he wrote in one to Miss Monroe, and when she wanted to retire, he wrote to her, “The intelligence of the nation [is] more important than the comfort of any one individual or the bodily life of a whole generation.” In a letter to H. L. Mencken thanking him for a copy of the latter’s In Defense of Women, Pound remarked, almost as an afterthought, “What is wrong with it, and with your work in general is that you have drifted into writing for your inferiors.” Could anyone have put it more precisely? Whoever wants to know what went on in the period from about 1910 to 1940, whatever he may think of his politics or economics, or even his poetry, will have to consult the letters of Ezra Pound–the proper function of the artist in society, he thought, was to be “not only its intelligence, but its ‘nostrils and antennae.’” And this, as his letters clearly show, Pound made a strenuous and, more often than not, successful effort to be.

How much of Lewis’ qualities were a result of his American heritage it would be hard to say, but there can be no doubt that much in both Pound and Eliot came from their American background. We may not have been able to give them what they needed to realize their talents and special qualities, they may even have been more resented than appreciated by many Americans, but that they did have qualities and characteristics which were distinctly American there can be no doubt. To this extent, at least, we can consider them an American gift to the Old World. In one of Eliot’s most beautiful works, The Rock, a “Pageant Play written on behalf of the forty-five churches Fund of the Diocese of London,” as it says on the title page, there are the lines, “I have said, take no thought of the harvest, but only of perfect sowing.” In taking upon themselves the difficult, thankless task of being the “terrifying voices of civilization” Eliot and his two friends, I am sure, didn’t give much thought of the possible consequences to themselves, of what there “might be in it for them,” but what better can one say of anyone’s life than “He sowed better than he reaped?’’

Originally published in Modern Age, June 1972. Reprinted with the permission of the Intercollegiate Studies Institute.

Henry Regnery (1912-1996) was an American publisher.

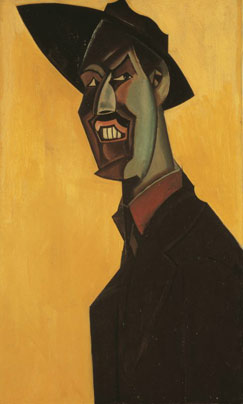

Firstly, his enormous breadth of talent overwhelms today’s overly-specialised critics in their imposed pigeon-holes: some still call him England’s greatest Twentieth Century portraitist and draughtsman, his substantial shelf of novels could keep another league of critics busy, and his volumes of social criticism a third. Next, nobody could be so marvellously abrasive without lots of practice, so whomever you adore from the first half of the Twentieth Century, Lewis said something snarky about him at least twice. Lastly, he had an almost magnetic attraction to being politically-incorrect, giving any sniffy modern who has not read Lewis a good excuse to dismiss him out of hand. So he is largely ignored: a big mistake.

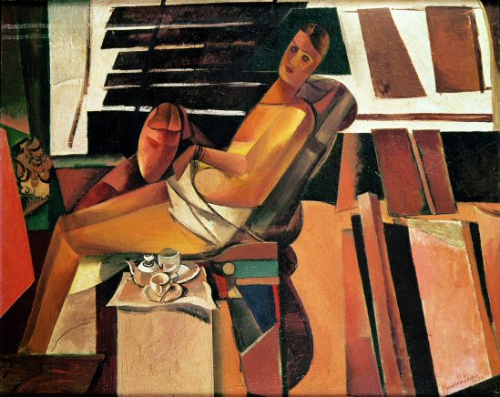

Firstly, his enormous breadth of talent overwhelms today’s overly-specialised critics in their imposed pigeon-holes: some still call him England’s greatest Twentieth Century portraitist and draughtsman, his substantial shelf of novels could keep another league of critics busy, and his volumes of social criticism a third. Next, nobody could be so marvellously abrasive without lots of practice, so whomever you adore from the first half of the Twentieth Century, Lewis said something snarky about him at least twice. Lastly, he had an almost magnetic attraction to being politically-incorrect, giving any sniffy modern who has not read Lewis a good excuse to dismiss him out of hand. So he is largely ignored: a big mistake. Its flat, mechanistic images were fine teething-material for Lewis’s draughtsman’s eye and unerring hand, and Vorticism proved a good marketing platform for the ambitious young artist at a time when various Modernist movements seemed to run a dime a dozen: Cubism, Futurism, Tubism, Suprematism, Expressionism, Verismus (may I stop now?) all trying to cram art into an ideological suitcase that was, of course, fully branded, wholly marketable and potentially lucrative. Ultimately, after a stint as an artilleryman, Lewis returned home and moved on, while Vorticism became what veteran art-critic Brian Sewell calls “in the history of western art, no more than a hapless rowing-boat between Cubism and Futurism, the Scylla and Charybdis of the day.”

Its flat, mechanistic images were fine teething-material for Lewis’s draughtsman’s eye and unerring hand, and Vorticism proved a good marketing platform for the ambitious young artist at a time when various Modernist movements seemed to run a dime a dozen: Cubism, Futurism, Tubism, Suprematism, Expressionism, Verismus (may I stop now?) all trying to cram art into an ideological suitcase that was, of course, fully branded, wholly marketable and potentially lucrative. Ultimately, after a stint as an artilleryman, Lewis returned home and moved on, while Vorticism became what veteran art-critic Brian Sewell calls “in the history of western art, no more than a hapless rowing-boat between Cubism and Futurism, the Scylla and Charybdis of the day.” In his 1928 “The Doom of Youth,” he described a cult that plagues us yet. A society that destroys faith in the hereafter can live only for earthly life, taking refuge from death in an unnatural fixation with youth and protracted adolescence; hence maintaining the appearance of youth until it becomes ludicrous. Since real youths lack experience, achievements and contacts, “official” public youths will be older and older. Politicians, he predicted, will jump onboard with bogus youth-wings, nevertheless controlled by middle-aged party-apparatchiks; presupposing the Hitler Youth Movement and even the fat, balding and comically-inept, 50-year-old, KGB “youth representatives” sent to international youth conferences to mingle with real Western and Third World teenagers into the 1980s. On to then-trendy monkey-gland treatments, more complicated cosmetics and foundation-garments, real and fake exercise regimens and the rest, until nowadays where in any Florida geriatric home (“God’s waiting-room,” my dad calls it) are toothless, pathetic wrecks hobbling around dressed as toddlers.

In his 1928 “The Doom of Youth,” he described a cult that plagues us yet. A society that destroys faith in the hereafter can live only for earthly life, taking refuge from death in an unnatural fixation with youth and protracted adolescence; hence maintaining the appearance of youth until it becomes ludicrous. Since real youths lack experience, achievements and contacts, “official” public youths will be older and older. Politicians, he predicted, will jump onboard with bogus youth-wings, nevertheless controlled by middle-aged party-apparatchiks; presupposing the Hitler Youth Movement and even the fat, balding and comically-inept, 50-year-old, KGB “youth representatives” sent to international youth conferences to mingle with real Western and Third World teenagers into the 1980s. On to then-trendy monkey-gland treatments, more complicated cosmetics and foundation-garments, real and fake exercise regimens and the rest, until nowadays where in any Florida geriatric home (“God’s waiting-room,” my dad calls it) are toothless, pathetic wrecks hobbling around dressed as toddlers.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Percy Wyndham Lewis (1882-1957), est considéré comme le fondateur du seul mouvement culturel moderniste indigène en Grande-Bretagne. Cependant, on le met rarement sur le même plan que Ezra Pound, James Joyce, T. S. Eliot, et d’autres de sa génération [1]. Lewis était l’une de ces nombreuses figures culturelles qui rejetaient l’héritage du XIXe siècle – celui du libéralisme bourgeois et de la démocratie, qui pesait sur le XXe.

Percy Wyndham Lewis (1882-1957), est considéré comme le fondateur du seul mouvement culturel moderniste indigène en Grande-Bretagne. Cependant, on le met rarement sur le même plan que Ezra Pound, James Joyce, T. S. Eliot, et d’autres de sa génération [1]. Lewis était l’une de ces nombreuses figures culturelles qui rejetaient l’héritage du XIXe siècle – celui du libéralisme bourgeois et de la démocratie, qui pesait sur le XXe.

Un environnement artistique sain requiert l’ordre et la discipline, pas le chaos et la fluctuation continuelle. C’est le grand conflit entre le « romantique » et le « classique » dans les arts. Cette dichotomie entre « classique » et « romantique » est représentée en politique par la différence entre la philosophie du « Temps » et celle de l’« Espace », cette dernière étant illustrée par la philosophie de Spengler. A la différence de beaucoup d’autres représentants de la « Droite », Lewis était fermement opposé à l’approche historique de Spengler, critiquant son Déclin de l’Occident dans Time and Western Man. Pour Lewis, Spengler et d’autres « philosophes du Temps » reléguaient la culture dans la sphère politique. Les interprétations cycliques et organiques de l’histoire sont vues comme « fatalistes » et démoralisantes pour la survie de la race européenne. Lewis résumait la thèse de Spengler comme suit : « Vous les Blancs, êtes sur le point de vous éteindre. Tout est fini pour vous ; et je peux vous le prouver par le résultat de mes recherches, et par ma nouvelle science de l’histoire, qui est bâtie sur le grand système du temps… » [36].

Un environnement artistique sain requiert l’ordre et la discipline, pas le chaos et la fluctuation continuelle. C’est le grand conflit entre le « romantique » et le « classique » dans les arts. Cette dichotomie entre « classique » et « romantique » est représentée en politique par la différence entre la philosophie du « Temps » et celle de l’« Espace », cette dernière étant illustrée par la philosophie de Spengler. A la différence de beaucoup d’autres représentants de la « Droite », Lewis était fermement opposé à l’approche historique de Spengler, critiquant son Déclin de l’Occident dans Time and Western Man. Pour Lewis, Spengler et d’autres « philosophes du Temps » reléguaient la culture dans la sphère politique. Les interprétations cycliques et organiques de l’histoire sont vues comme « fatalistes » et démoralisantes pour la survie de la race européenne. Lewis résumait la thèse de Spengler comme suit : « Vous les Blancs, êtes sur le point de vous éteindre. Tout est fini pour vous ; et je peux vous le prouver par le résultat de mes recherches, et par ma nouvelle science de l’histoire, qui est bâtie sur le grand système du temps… » [36].

Comme nous l’avons vu, Lewis se moquait paradoxalement de la croyance de Pound au crédit social, mais il était très conscient du pouvoir de l’usure et des « Empereurs de la Dette ». Il examina cela une nouvelle fois en 1948 en écrivant :

Comme nous l’avons vu, Lewis se moquait paradoxalement de la croyance de Pound au crédit social, mais il était très conscient du pouvoir de l’usure et des « Empereurs de la Dette ». Il examina cela une nouvelle fois en 1948 en écrivant :

The Apes of God happens to be one of the most devastating satires to be published in the English language since the days of Dryden and Pope. It appeared in a

The Apes of God happens to be one of the most devastating satires to be published in the English language since the days of Dryden and Pope. It appeared in a