Standardbearers: British Roots of the New Right [2]

Standardbearers: British Roots of the New Right [2]

Edited by Jonathan Bowden, Eddy Butler, and Adrian Davies.

With a Foreword by Professor Anthony Flew

Beckenham, Kent: The Bloomsbury Forum, 1999

Somewhere between the “hug-a-hoodie” Toryism of David Cameron’s Conservatives, and those far-right parties considered beyond the pale, is believed to lie a broad “respectable” middle ground of British nationalist politics. Whether or not it really exists, contenders keep trying to fill it.

The most recent is Nigel Farage’s UKIP, which officially backs a program of ultra-Tory economic nationalism (anti-EU) but now finds that its main appeal is really to regional anti-immigration Labour voters.[1] Sir Oswald Mosley tried to strike a middle way with his Union Movement in the 1950s and ’60s, but that venture was doomed (of course) because Mosley means not-mainstream.

The Monday Club in the Conservative Party seemed to fill the gap well for a good long while in the 1960s-’80s: it opposed Kenyan independence, supported Rhodesia, opposed nonwhite immigration, and generally took a staunchly nationalist, anti-Left stance on the things that mattered. However, the experience of Thatcherism and Political Correctness in the ’80s and ’90s pushed the Monday faction into a kind of dotty irrelevance (“I really cannot bear the Monday Club. They are all mad . . .” wrote Alan Clark in his diary)[2], until the Party finally cut ties to the Monday Club in a “purge of rightwing extremists.”[3][4]

The volume at hand, Standardbearers, seems to have been assembled in the late 1990s to help forge a new middle-way Rightism. It was the early Tony Blair years. The Conservatives were in the wilderness, in thrall to Political Correctness, and the respectable Right had lost its way. Tony Blair had a way of dismissing his opponents’ arguments by describing them as “the past.” As Antony Flew describes in the Foreword:

The volume at hand, Standardbearers, seems to have been assembled in the late 1990s to help forge a new middle-way Rightism. It was the early Tony Blair years. The Conservatives were in the wilderness, in thrall to Political Correctness, and the respectable Right had lost its way. Tony Blair had a way of dismissing his opponents’ arguments by describing them as “the past.” As Antony Flew describes in the Foreword:

[A]t the Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting in Edinburgh in 1997 everything traditionally Scottish was out. No Scottish regiment marched up the Royal Mile with its band playing. Instead the visiting ministers were shown a video announcing: “There is a new British identity,” and displaying pop stars and fashion designers.[5]

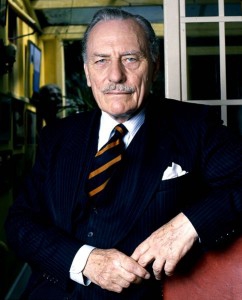

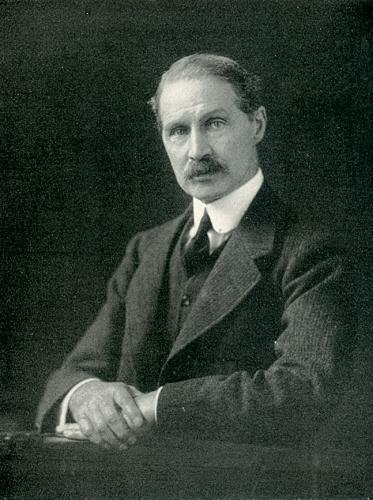

Picture: Enoch Powell

This corrective to national amnesia and Cool Britannia is not a collection of political tracts. It doesn’t assail broad issues of race and culture, or ride obscurantist hobbyhorses about IQ standard-deviations or Austrian Economics, or explain how Free Markets are the backbone of a Free Society. It has no specific axe to grind. It is merely an old-fashioned collection of profiles of eminent men, in the manner of Plutarch or Strachey or JFK. If it has any overarching objective, it that of moral rearmament by finding a usable past. The writers look at discarded national aspirations, and take a keen look at half-forgotten or misremembered Englishmen from the 18th century onward.

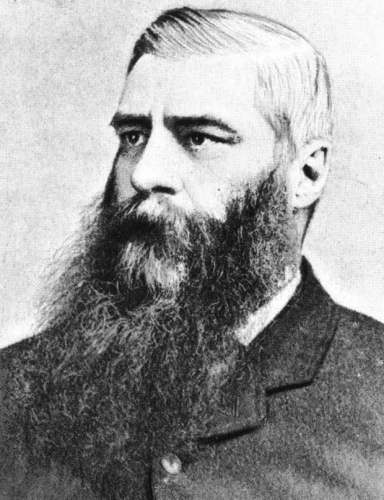

G. A. Henty

We begin by rehabilitating the spirit of national and imperial greatness, and this is done with studies on G. A. Henty and John Buchan (by Eddy Butler and William King, respectively). The first was the originator of the “ripping yarns” genre of derring-do and imperial adventure that filled Boys’ Own type of magazines in the latter 19th century and had enormous influence on popular and serious literature. Kipling’s fiction, and Buchan’s, and even some of Hemingway’s and Orwell’s, derive in part from Henty.

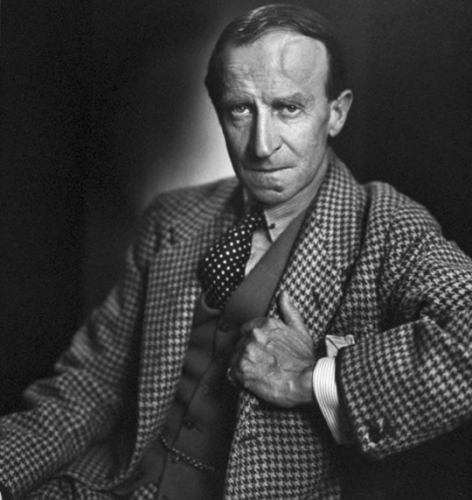

John Buchan

John Buchan’s influence in turn is even more marked today because Buchan (journalist, speechwriter, and at one point Governor-General of Canada) wrote The Thirty-Nine Steps, which was the ur-espionage thriller, giving rise both to the novels of both John LeCarré and Ian Fleming. Thus, George Smiley and James Bond both have their roots in the high noon of the late 19th century British Empire. Though the memory of that Empire has been derided as something embarrassing for the past 60 or 70 years, its ultimate product, Mr. Bond, still stands, exciting and new.

The book’s authors find nationalism flowering in odd places. There is a short, fascinating essay called “Bax” by Peter Gibbs, and while it initially appears to be a tribute to the 20th century orchestral composer Sir Arnold Bax, it quickly moves on to a kind of rhapsody to exemplars of English (or “British”) national culture. Two whom Gibbs prizes the most are the composer Ralph Vaughn Williams, whose “folk-song settings and arrangements certainly reveal a nationalist outlook”; and the wildly romantic and mystical cinema of filmmaker Michael Powell (The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, A Canterbury Tale).

Some of the book’s portraits are very predictable for a rightist anthology (Samuel Johnson, Edmund Burke, Hilaire Belloc, G. K. Chesterton), while others are unexpected and appear to reflect an author’s expertise or passion (Benjamin Disraeli, John Maynard Keynes). One curious cultural figure well known to Counter-Currents readers but otherwise obscure, is the final portrait in the book, Bill Hopkins, here profiled and interviewed by the late Jonathan Bowden. Bill Hopkins was perhaps the most obscure of the Angry Young Men of 1955-59. As he recounts here, he was a working journalist who was given a contact for a novel, The Divine and the Decay, which was eventually withdrawn and pulped, because someone at the publishing house bad-mouthed him as a subversive of the fascistic tendency. Thereafter Hopkins lay low, wrote under pseudonyms, edited the very first issue of Penthouse in the mid-1960s, and slowly amassed a fortune. The one true rebel and bohemian in the book, he is also the only character who was alive in the 1990s and able to tell his story in his own querulous voice.

On the political side, I was glad to see the almost entirely neglected Bonar Law here (in a brief biography by Adrian Davies). Law was perhaps the last Conservative PM to be truly conservative. The main reason we hardly ever hear of him today is that there were so many sparkly and opportunistic Liberal politicians on the scene (Winston Churchill, Lloyd George, H. H. Asquith) when he was in opposition; and when Law finally succeeded to the premiership in 1922, he served only a short time before succumbing to throat cancer. Here and in his treatment of Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, Adrian Davies spends a good deal of space describing the Home Rule crisis on the eve of the Great War: how Army officers were threatening to mutiny if asked to put down rebellions in Ulster, and how Asquith and the Liberals exploited the whole Home Rule issue for political gain. (A portrait of Sir Edward Carson, by Ralph Harrison, covers parallel ground.)

Bonar Law

As this is partisan history, these retellings are sometimes tendentious. Bonar Law, Edward Carson, and the Unionists/Conservatives were at least as pragmatic and opportunistic as the Liberals. After all, their opposition to enactment of Irish Home Rule 1912-1914 rested upon the odd position that the little patch of Ireland around Belfast was a sanctuary, a special spot, which must never be ruled by a Dublin parliament, unless and until Belfasters give their collective permission. (Presumably Ulstermen had not made such special pleading back in 1800, when the Act of Union was passed and the Dublin parliament abolished.) The writers’ reference to the northeast corner of Ireland as “North” and the remainder of the island as “South,” is a quaint example of political cant, but a useful and enduring one.

Another Englishman whose career got snagged on the Irish problem was the classics scholar Enoch Powell, here profiled by Sam Swerling. For most of his long tenure as MP, 1950-1987—first for the Conservatives, then for the Ulster Unionists—Powell was a steady, unswerving champion of national integrity and self-reliance. “He regarded the Commonwealth as a farcical institution and the United Nations as a vehicle for American aggrandisement and sabre rattling.”[6] Powell was perennially suspicious of America and even more so of the EEC, Britain’s membership in which he considered to be a political question, not an economic one.

Today he is largely remembered for his April 1968 “Rivers of Blood” speech, decrying nonwhite immigration. Although this made screaming headlines and caused Edward Heath to dismiss Powell from his shadow cabinet, the speech was not the watershed it is usually made out to be. Powell was not the first Conservative to speak out on the Caribbean black problem, and his concern was not race per se but rather preservation of national integrity. Nevertheless, with his oratorical verve and his mustache, Enoch Powell excited some nationalist hearts longing for a new Mosley.

But that role was quite inapposite to this poet/classicist’s tastes and abilities. “Powell never quite saw himself as a latter-day Mussolini marching on London with nationalist legions in his wake.”[7] Moreover, any racial-nationalist movement that might have been aborning in 1968, was effectively smothered in its crib. As though on cue, civil-rights marchers began agitating in Belfast, and by accident or design, these new developments so distracted Powell and the Conservatives that nothing more was heard from them on the New Immigration issue.

One useful figure I wish had been in here and is not, is Alan Clark MP, the arch-Tory historian, diarist, animal-lover, and cabinet secretary who never let political expediency get in the way of his wit, and died the same year this was published.[8]

I highly recommend this book [2] to all who search for foundations for a New Right.

Notes

1. Financial Times, 30 August 2015 [7].

2. Alan Clark, Diaries: Into Politics. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. 2000. p. 337.

3. Conservative leader Iain Duncan Smith broke ties with the Monday Club in October 2001 because of its “inflammatory views on race, such as the voluntary repatriation of ethnic minorities.” http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2001/oct/19/uk.race [8]

4. A few months later, in May 2002, IDS publicly sacked a minor shadow minister, Ann Winterton, for telling attendees at a rugby dinner a mild joke about a Cuban, a Japanese, and a Pakistani. http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2002/may/06/race.conservatives [9]

5. Standardbearers, p. V.

6. ibid., p. 128

7. ibid., p. 126.

8. When someone called Clark a fascist in the Guardian, he is supposed to have written the editor: “I am not a fascist. Fascists are shopkeepers. I am a Nazi.” (Alas, I have been unable to locate the letter.)

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les commentaires sont fermés.