Editor’s Note: This is the second of two articles on this topic, the first of which was published last week. There has been some controversy over my decision to allow this author to write under a pen name. I know the author’s identity and while his arguments are surely controversial, I am confident in his sourcing and subject matter expertise. I carefully considered his request to use a pen name. I decided that this case reasonably meets the standards for such protection published on our site. The author, in my view, can reasonably and seriously fear for his professional employment and safety publishing under his real name. -RE / Update: The author’s pen name has been changed to protect someone with the same name who has nothing to do with the article.

I was not surprised to see my first article greeted with so much outrage by those who adhere to the conventional Western narrative of the civil wars in Iraq and Syria as well as the larger tumult of the Middle East. In truth, these conflicts are not so easily defined by the easy sectarian narrative offered in the Western press. I argued that Western elites were surrendering to and even embracing the Saudi definition of what Sunni identity should mean. And I provided accounts of the conflicts in Syria and Iraq that do not comport with what you likely have been reading in the newspapers.

But there is far more to the story. It is worth recounting how we got to this point. In the aftermath of the toppling of Saddam and his regime, Iraq’s Sunnis were betrayed by many of their own religious, political, and tribal leaders who demanded that they boycott the post-2003 political order by waging an insurgency against the world’s most powerful military and the government it sought to stand up and support. Of course, it did not help that the U.S.-led occupation and the security forces it empowered victimized Sunni Iraqis disproportionately. The American military’s posture was more aggressive in Sunni-majority areas, and Iraqi security forces collaborated with Shia death squads in pursuit of a vicious counterinsurgency strategy that saw bodies piled up and neighborhoods cleansed. Iraqis en masse suffered from a collective trauma that will take decades to recover from. But hardline Sunni rejectionists and their Western backers have claimed that if Sunnis are not “empowered” then there is no alternative available to them but the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). When adopted by Westerners, this argument seems to support Sunnis but actually represents a very low opinion of them because it holds that Sunnis require disproportionate political power to avoid becoming terrorists. Since 2003, Sunni rejectionists have pushed this narrative to hold Iraq hostage, blackmailing Baghdad and its allies like gangsters in a protection racket.

If Sunni leaders did not receive the government position or the business contract they wanted, they would then claim persecution on account of their Sunni identity, switch sides, gather their relatives, and use violence. Examples of this phenomenon from early 2013 include:

Still, the West has pressured the Iraqi government to allow into its ranks Sunni representatives like the above, who oppose the very legitimacy of the government and the notion of a Shia ruler. There were no Shias in the Anbar or Ninawa provinces to threaten Sunnis. At best, they were politically disgruntled, which is an insufficient reason to embrace the world’s most vicious terrorist organization.

The Jihad Returns to Haunt Syria

The interplay between the conflict in Iraq and the Syrian civil war created a perfect storm. The U.S.-led occupation of Iraq and the sectarian war it ignited influenced how Syrian Sunnis thought of themselves. The Syrian government was warned that it was next in line for regime change, and it took preemptive measures to scuttle the American project in Iraq. By supporting or tolerating insurgents (including al-Qaeda) for the first three years of the occupation, Damascus sought to bog the Americans down. But by then, the Syrian government had lost control of its eastern border. After 2006, at least one million mostly Sunni Iraqis fled into Syria, including some with ties to the insurgency who either came to Syria to facilitate insurgent operations in Iraq, to find a safe place for them and their families, or both. Many former al-Qaeda in Iraq members had fled to Damascus and were living normal lives as family men and laborers before the Syrian crisis erupted in 2011. In my own interviews with detained members of Jabhat al-Nusra, I learned that when the Syrian insurgency started, these men were contacted by old friends who told them, in effect, “We’re putting the band back together.” Many of these Iraqis formed the early core of al-Nusra, which until recently was al-Qaeda’s Syrian affiliate.

By 2010 or 2011, Iraq appeared to be stable. When the uprising started in Syria and the country became unstable, many of the Iraqi Sunni rejectionists returned to Iraq from their Syrian exile. Insurgents in Syria had created failed state zones, power vacuums full of militias, and a conservative Islamist Sunni population mobilized on sectarian slogans. The Turks were letting anyone cross into Syria, which was exploited most successfully by jihadists. By the summer of 2012, many local Syrians saw the arrival of foreign fighters in a positive light, as if they were members of the Lincoln Battalion of foreign volunteers in the Spanish Civil War. As I myself witnessed, they were welcomed and housed by Syrians, who facilitated their presence and cooperated with them.

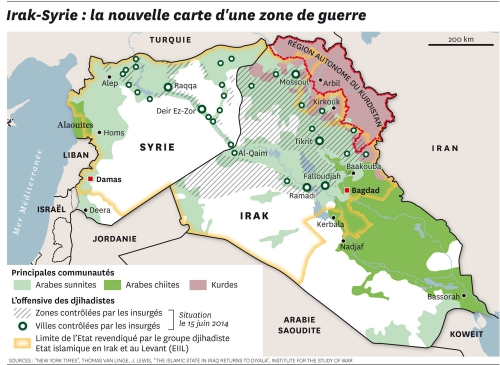

These thousands of foreign fighters in Syria eventually sided in large numbers with ISIL, seizing parts of Syria. From there, the group was able to launch its offensive into Iraq in the summer of 2014 (although the ground in Mosul had been prepared by the jihadists for quite some time). The prospect of a Sunni sectarian movement seizing Damascus evoked their dreams of expelling the Shia from Baghdad (although the difference, of course, is that Baghdad is a Shia-majority city, unlike Damascus). The Syrian uprising mobilized public and private Gulf money for a larger Sunni cause in Syria, Iraq, and elsewhere in the region. A lot of this support went to the Sunni rejectionists of Iraq, who staged sit-ins and demonstrations in majority-Sunni cities in Iraq. Meanwhile, Al Jazeera had transformed from the voice of Arab nationalism into the voice of sectarian Sunnis, virtually promoting al-Qaeda in Syria and celebrating the initial ISIL “revolutionaries” in Iraq.

From Syria, Back to Iraq

In 2012, as jihadists gathered in centers of rebellion around Syria, Sunni rejectionists in Iraq allowed jihadists to re-infiltrate their ranks as they launched this campaign of demonstrations, thinking they could use the presence of these men as leverage against the government. At the time, al-Qaeda and ISIL forerunner Islamic State of Iraq were still united. They had systematically assassinated key leaders of the “Awakening” movement, neutralizing those that could have blocked the jihadist rapprochement with Sunni leaders in Iraq. From 2006 to 2009, they also assassinated many rival insurgent commanders to weaken alternative armed movements. Former insurgents described to me how just before the Americans withdrew from Iraq in 2011, insurgent leaders from factions as politically diverse as the Naqshbandis, the Islamic Army, the Army of the Mujahedin, and the 1920 Revolutions Brigades all met in Syria to plan to take the Green Zone in Baghdad (an ambition that was, ironically, accomplished this year by Shia rather than Sunni masses). While these groups initially lacked the ability to take the Green Zone, they made their move when the demonstrations started with the help of the Islamic State, which saw utility in cooperating with these groups, for the time being.

When Sunni protestors in 2012 and 2013 filled squares in Ramadi, Mosul, Hawija, Falluja, and elsewhere chanting “qadimun ya Baghdad (“we are coming, Baghdad”), it was hard for the government and average citizens in Baghdad not to interpret this as a threat from various Sunni-majority cities. These were not pro-democracy demonstrations. They were rejecting the new order — an elected government — and calling for overthrow of the Shia.

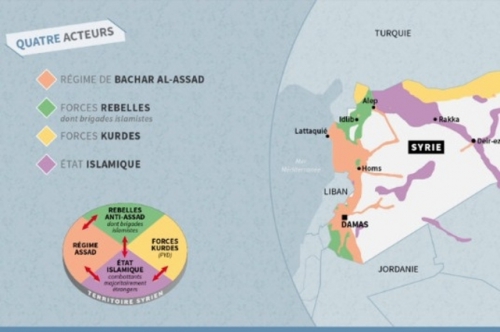

Sunni rejectionist leaders rode this wave of support and became a key factor in how easily ISIL later seized much of the country. According to Iraqi insurgents I spoke to, ISIL’s leaders initially thought that they would have to depend on former insurgents, including Baathists, as a cover to gain support. While ISIL’s jihadists did initially cooperate with some of these groups, it was not long until ISIL discovered it did not need them and purged them from its newly seized territories. Many Sunni rejectionist leaders, now understanding the horror of what they helped to unleash, then fled, leaving their populations displaced, destroyed, and divided. Likewise in Syria, Sunni rejectionists and their Western supporters argued that the only way to defeat ISIL is to topple Assad, and thus placate their sectarian demands. And the West somehow believes that they are representative of Syria’s Sunnis writ large. The secular or progressive opposition activists amenable to pluralism unfortunately have no influence because they have no militias of their own.

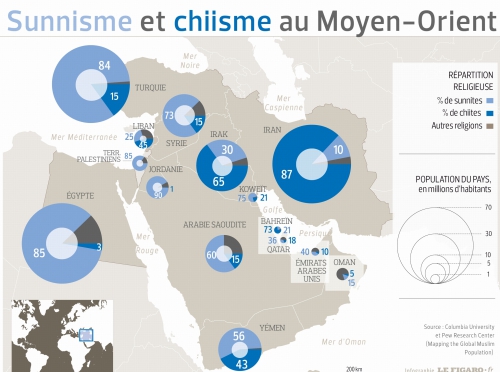

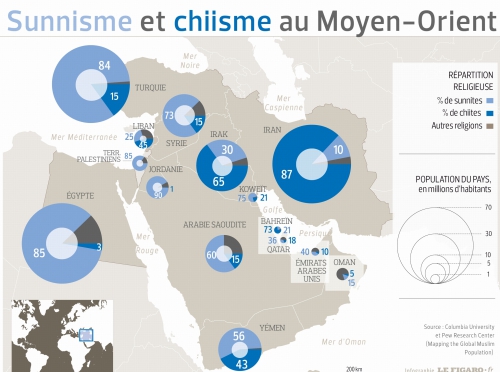

The Evolution of Sectarian Identity in the Modern Middle East

There is a major crisis within Sunni identity. Sunni and Shia are not stable, easily separable categories. Twenty years ago, these terms meant something else. The 2003 invasion of Iraq was the geopolitical equivalent of the asteroid that caused the extinction of the dinosaurs. Just as species were killed off or arose thanks to that cataclysm, so too in the Muslim world, old identities were destroyed while new ones were created, as discussed by Fanar Haddad at the Hudson Institute. One of these new identities was the post-Saddam “Sunni Arab,” treated by their Western taxonomists as if they were an ethnic group rather than a fluid, fuzzy, and diverse religious sect. For centuries, Sunni identity was conflated with “Muslim” and the identity of “Muslim” was distinct from members of heterodox or heretical sects. Generally speaking, Shias living in areas dominated by Sunnis were subordinate to them juridically and by custom. The war in Iraq helped create a sense of “Sunni-ness” among otherwise un-self-conscious Sunni Muslims, and it also overturned an order many took for granted. To make matters worse, not only were Shia Islamist parties (such as Dawa and the Supreme Council) brought to power (as well as Sunni Islamist parties such as the Islamic Party), but Sunnis bore the brunt of the occupation’s brutality (while Shias bore the brunt of the insurgency’s brutality).

The result is that we now see Sunni identity in the way that the Saudis have been trying to define it since they began throwing around their oil wealth in the 1960s to reshape Islam globally in the image of Wahhabism. Haddad explains:

[T]he anti-Shia vocabulary of Salafism has clearly made some headway in Iraq and indeed beyond. This is only to be expected given that Salafism offers one of the few explicitly Sunni and unabashedly anti-Shia options for Sunnis resentful of Shia power or of Sunni marginalization.

In other words, we now see a Sunni identity in Iraq that dovetails with Saudi Wahhabism. And the response in the West is to reinforce this!

Ironically, we do something similar with Shia identity. Westerners (and sectarian Sunnis) believe Shia are all the same and all an extension of Iranian (Persian) theocratic power — but they are not, and assuming this is the case has negative effects in the region. It is true that there is far more political coherence to Shia religious identity in the Middle East compared to the Sunni, but placing the center of Shia identity in Iran dramatically misconceives the center of power in the Shia Arab world. To be a sect, you need to have a sense of coherence with centers of power through which someone speaks on your behalf. Shias know what they are and who their leaders are. In Iraq and even beyond its borders, Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani looms larger than others for Shia, especially but not exclusively in the Arab world. The Sunnis have no equivalent leader.

We tend to view Hizballah or the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps solely as threats to the West or Israel, but they are also mature local actors with influence on other Shias. Before 2011, the Shia axis was merely an idea. Compared to the Shia of Lebanon, Syria, and Iran, Iraqi Shias were relatively isolated from neighboring countries and struggles. They were insular, and their aspirations were more mundane, as they were discovering middle-class life. Just as Sunni rejectionists playing ISIL’s game in radicalizing their populations, this process also radicalized many Iraqi Shia, mobilizing them in self-defense and even launching some of them into Syria to support Assad. Now Shias from Iraq, Lebanon, Iran, Syria, Afghanistan, and elsewhere are cooperating on the battlefield. From 2003 until the present day, Shia civilians have been targeted in Iraq nearly every day, not to mention in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen.

Despite this virtual war on Shias supported and condoned by major Sunni religious leaders, Shias have remained much more restrained than their Sunni counterparts. What is keeping Lebanese, Iraqi, and Syrian Shias from committing massacres and displacing all Sunnis in their path? By and large, it is a more responsible religious leadership guiding them from Qom or Najaf, organizing Shias and offering structure and discipline. According to interviews I have conducted in the region, Hizballah leaders privately complain to Iraqi Shia leaders about their behavior, condemning them for alienating and failing to absorb Sunnis. They scold these leaders for their violations, reminding them that when Hizballah expelled the Israeli occupation, it did not blow up the houses of the many Christian and Shia collaborators or violently punish them.

When we say Sunni, what do we mean? There are many kinds in too many countries: Sunni Kurds, Uighurs, Senegalese, tribal Arabs, urbanites in Cairo, Damascus, Baghdad, Bedouins, and villagers. You cannot make Sunnism into a politically coherent notion unless you are willing to concede to the narrative of al-Qaeda, ISIL, or the Muslim Brotherhood. The latter has historically avoided the explicit, toxic sectarianism of the jihadi groups, but it is also a broken and spent force as its projects in the Arab world having largely failed.

Before the rise of the modern Arab nation-state, cities possessed a state-sponsored moderate Islam that was involved in the law. Urban Sunnis were largely part of the moderate Hanafi school of Sunni jurisprudence. This school, one of four mainstream Sunni schools, is the most tolerant and flexible. The countryside historically practiced folk Islam or considered itself Shia, Sufi, or Alawi. Hanafization took place because it was the religion of elites, the religion of empire, the religion of Ottomans. Today, there is no state Hanafi Islam and other moderate institutions. traditional Sunni Islam of the state has crumbled.

It is therefore impossible to find a genuine center of Sunni power. It is not yet Saudi Arabia, but unless the West changes the way it sees the Middle East, that will become a self-fulfilling prophecy with cataclysmic results.

Saudi Arabia is the dominant state supporting Sunni Islam today via mosques, foundations, and Islamic education. As a result, Salafism — a movement that holds Islam should be practiced as it was by the Prophet Mohammad and his companions — is the new religion of empire and its rejectionist tendencies are a danger to all countries with a Sunni population, from Mali to Indonesia. One reason why Syrian Sunnis became so radicalized is that many of them spent years working in the Gulf, returning with different customs and beliefs. When a Gulf state supports the opening of a mosque or Islamic center in France or Tanzania, it sends its Salafi missionaries and their literature along with it. Competing traditions, such as Sufism, are politically weak by comparison. Muslim communities from Africa to Europe to Asia that lived alongside for centuries alongside Christians, Buddhists, and Hindus are now threatened as Sufis and syncretic forms of Islam are pushed out by the Salafi trend.

I have come to understand that in its subconscious, the institutional culture of the Syrian regime views this transnational Sunni identity as a threat and it is one reason why Alawites are overrepresented in the Syrian security forces. This is partly for socioeconomic reasons, but it is also seen by the regime as key to preserving the secular and independent nature of the state. Their rationale is that Alawites as a sect have no relations or connections or loyalties outside of Syria. As a result, they cannot betray the country by allying with the Saudis, Qataris, or the Muslim Brotherhood, nor can they suddenly decide to undo the safeguards of secularism or pluralism inherent in the system.

The vision propagated by the Islamic State is consistent with the Salafi interpretation of Islamic law, which is why Egypt’s al-Azhar or other institutions of “moderate Islam” cannot be counted upon to stem the tide of Salafism. Al-Azhar, traditionally the preeminent center of Sunni Islamic learning, failed to reject ISIL as un-Islamic. Leading Sunni theologians in the Arab world have condemned ISIL on the grounds that the group is excessive, applying the rules wrong, or pretending to have an authority it does not legally possess, but they do not cast the movement as un-Islamic and contrary to Sharia. Only technical differences separate the ideology of Jabhat al-Nusra from that of ISIL or Ahrar al-Sham or even Saudi Arabia. The leadership of al-Nusra also holds takfiri views, and their separation from al-Qaeda did not involve a renunciation of any aspect of its toxic ideology. Ahrar al-Sham likewise appeals to the same tendencies.

Curiously, U.S. political leaders seem more dedicated than anyone in the world to explaining that ISIL is not true to the tenets of Sunni Islam. The problem is that Muslims do not look to non-Muslim Western political leaders as authoritative sources on Islam.

The irony, of course, is that the main victims of Salafization are Sunnis themselves. Sunni elites are being killed, and the potential to create Sunni civil society or a liberal political class is being made impossible. ISIL seized majority-Sunni areas. Main Sunni cities in Iraq and Syria are in ruins and their populations scattered, and, obviously, the Syrian Arab Army’s brutal campaign has also contributed to this. Millions of Sunnis from Syria and Iraq are displaced, which will likely lead to a generation of aggrieved Sunni children who will receive education that is extreme, sectarian, and revolutionary or militant in its outlook — if they get any education at all. Already, many live in exile communities that resemble the Palestinian refugee camps, where a separate “revolutionary” identity is preserved.

The Sunni public has been left with no framework. Sunnis represent the majority of the Middle East population, and yet having in the past embraced the state and been the state, they now have nothing to cohere around to form any robust and coherent movement or intellectual discourse. A movement built around the idea of Sunnism, such as the foreign-backed Syrian opposition and some Iraqi Sunni leaders, will create an inherently radical region that will eventually be taken over by the real representatives of such a notion — al-Qaeda, ISIL, or Saudi Arabia.

State Collapse and Militias Fighting for Assad

Five years of bleeding has weakened the Syrian army and forced it to rely upon an assortment of paramilitary allies, nowhere more so than in Aleppo. On July 28, the Russians and Syrians offered insurgents in east Aleppo amnesty if they left, and they invited all civilians to come to the government-held west Aleppo. This offer was explicitly modeled on the 2004 evacuation of Falluja’s residents, which came at a high price, in order to retake the city from al Qaeda in Iraq. In response, Sunni extremists called for an “epic” battle in Aleppo. The jihadist offensive was named after Ibrahim al Yusuf, a jihadist who killed dozens of Alawite officer candidates at the Aleppo military academy in 1979 while sparing Sunni cadets. It is led by Abdullah Muheisni, a shrill Saudi cleric who called upon all Sunnis to join the battle and who marched into the city triumphantly. Up to two million people in west Aleppo are threatened by the jihadist advance, protected by an army hollowed out after five years of attrition.

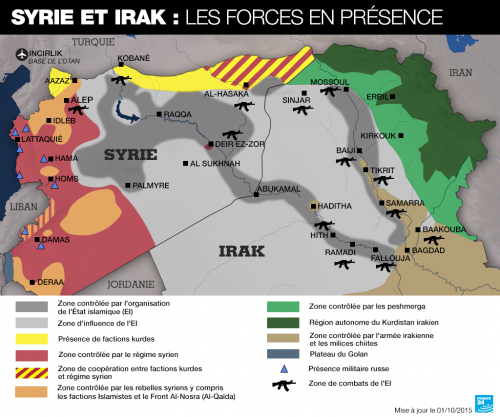

This has forced the Syrian regime to rely on Shia reinforcements from Iraq, Lebanon, Afghanistan, and Iran. There is a big difference between these Shia reinforcements and their jihadist opponents. The Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) and others have come to Syria to help the Syrian army prevent further state collapse. They would not be there had a foreign-backed insurgency not weakened the army. The foreign Shia militias do not interact with Syrian civilians and are only on the frontlines. They are not attempting to impose control. Even the worst of the Iraqi Shia militias avoid overt sectarianism and work hard to stress that the enemy is not all Sunnis but rather those who advocate for a violent Wahhabi ideology. Moreover, I learned in interviews that the regime has arrested and even executed unruly Shia militiamen.

Meanwhile, Muheisni and his hordes represent an explicitly totalitarian and genocidal ideology that endangers all people of the region who are not Salafi men. The Shia PMF units in Aleppo such as Kataeb Hizballah and Nujaba have plenty of Sunnis in Baghdad that they could massacre if they had an anti-Sunni agenda, and yet they leave them alone just as they do the Sunni civilians of government-held portions of Aleppo.

Finally, Iran and its non-Syrian Shia partners cannot establish roots in Syria or change its society as easily as some seem to think. As much as the Alawite sect is called Shia, this is not entirely accurate and they do not think of themselves as Shia. They are a heterodox and socially liberal sect that bears little resemblance in terms of religious practice or culture to the “Twelver Shias,” such as those of Iran, Iraq, or Lebanon. There is only a very tiny Twelver Shia population in Syria.

Many of the soldiers fighting in the Syrian army to protect Aleppo are Sunnis from that city, and most of the militiamen fighting alongside the army in various paramilitary units are Sunni, such as the mixed Syrian and Palestinian Liwa Quds and the local Sunni clan-based units. In Aleppo, it is very much Sunni versus Sunni. The difference is that the Sunnis on the government side are not fighting for Sunnism. Their Sunni identity is incidental. By contrast, the insurgents are fighting for a Sunni cause and embrace that as their primary identity, precluding coexistence. This does not, of course, mean the government should drop barrel bombs on their children, however.

The presence of Iraqi Shia militiamen is no doubt provocative and helps confirm the worst fears of some Sunnis, but the fact that these foreign Shia are supporting their Syrian allies does not negate the fact that there are many more thousands of Sunnis on the side of the government. Those foreign Shia militias believe, according to my interviews, that if they do not stop the genocidal takfiri threat in Syria, then Iraq and Lebanon will be threatened. Alawites and other minorities believe this too of course. But in Syria there is still a state and it is doing most of the killing, though not for sectarian reasons but for the normal reasons states use brutality against perceived threats to their hegemony. There have been exceptions such as the 2012 Hula or 2013 Baniyas massacres in which ill-disciplined local Alawite militiamen exacted revenge on Sunni communities housing insurgents, targeting civilians as well.

What is Washington to Do?

U.S. policy in the Middle East, especially in conflict zones and conflict-affected states, should be focused on (1) doing no harm and (2) making every effort to stop Saudi Arabia from becoming the accepted center of the Sunni Arab world or the Sunni world writ large, while (3) building and reinforcing non-sectarian national institutions and national forces.

America’s Troublesome Saudi Partners

As regards Saudi Arabia, many American thought leaders and policymakers have long understood the fundamental problems presented by this longstanding U.S. partner but the policy never changes. Indeed, U.S. policy has in many ways accepted and even reinforced the longstanding Saudi aim to define Sunni identity in the Arab world and beyond. It is dangerous to accept the Saudi narrative that they are the natural leaders of the Sunni world given the dangerous culture they propagate. Promoting a sectarian fundamentalist state as the leader of Arab Sunnis is hardly a cure for ISIL, which only takes those ideas a bit further to their logical conclusions.

Washington may not have the stomach to take a public position against the form of Islam aggressively propagated by its Saudi “partners,” but there must be an understanding that Wahhabism is a dangerous ideology and that its associated clerical institutions represent a threat to stability in Islamic countries around the world. The United States could seek to sanction media outlets, including satellite channels and websites, that promote this form of Islam. Think this is unprecedented? Washington has targeted Lebanese Hizballah’s al-Manar station with some success.

Syrian and Iraqi Sunnis are not holding their breath waiting to hear what Gulf monarchs will say. They wait only to see how much money might be in the envelopes they receive for collaboration. For leadership, Iraqi and especially Syrian Sunnis should be encouraged to look closer to home — to their own local communities and the state. The state should be strengthened as a non-sectarian body.

The Need for Non-Sectarian Institutions in the Middle East

In Washington’s policy circles, we often hear calls for Sunni armies and militias to “solve” Iraq and Syria. Yet Sunni armies already exist in these countries in the form of ISIL, al-Qaeda, and Ahrar al-Sham. The answer is not more Sunni armed groups.

If the goal is to excise jihadism, do not try to coexist with Sunni rejectionists advancing Saudi notions of Sunni identity. If Assad were fed to the jihadists as a sacrifice, then the next Alawite, Christian, Shia, secular, or “apostate” leader would become the new rallying cry for jihadists. Their goal is not merely the removal of one leader, but the extermination of all secularists, Shias, Alawites, Christians, and Jews, and others who are different — including fellow Sunnis. The Syrian government is often criticized for making little distinction between ISIL, Jabhat al-Nusra, Ahrar al-Sham, and the “moderates” who cooperate with them, but this misconceives how the Syrian state forces see the conflict. To them, any insurgent force with Islamist slogans is a slippery slope leading to the same result. Critics may complain that at various points in the war Syrian state forces spent more resources fighting the American-backed insurgents than ISIL, but this is because ISIL emerged largely in areas where the Syrian government had already been driven out. Meanwhile, the so-called moderates were the main day-to-day threat to government-held population centers such as Aleppo, Hama, Homs, Damascus, and Daraa.

It is irrational for the West to expect the Syrian government to focus on the enemies the West wants to see defeated while Western powers, along with Gulf countries and Turkey, are supporting insurgents that attack government forces which secure cities. The Syrian security forces have a finite amount of men, ammunition, fuel, and other resources, and they need to protect a great deal of military infrastructure, terrain, population centers, and supply lines. This naturally forces the regime to make choices. When foreign-backed insurgents attack state-held areas, the state’s security forces are less able to conduct operations elsewhere. For example, when American-backed insurgents cooperated with al-Qaeda and foreign fighters to seize cities in Idlib province last year, the Syrian Arab Army sent reinforcements from the east to Idlib. This left Palmyra wide open for ISIL to attack, which they did, seizing the ancient city. In February of this year, with the Cessation of Hostilities in place, the Syrian state was able to focus more resources on ISIL and retake Palmyra with Russian backing. ISIL and al-Qaeda thrive in stateless zones throughout the Muslim world. Supporting insurgents to create more such zones will only give such groups more space to occupy.

Every proposal to further weaken regime security forces leads to a greater role for Shia militias and the ill-disciplined militias the regime relies upon for support. Escalation by supporting proxies does not pressure the regime to negotiate. It only pressures the regime to use even more repressive and abhorrent tactics. The only compromises it makes are about which actors it will rely upon to defeat its enemies. As law and order breaks down, even Alawite militias have lost respect for the security forces. What is left of the Syrian state is failing, and the West bears some responsibility for that.

As jarring as this may sound to many Western readers, the Syrian government offered a model of secular coexistence based on the idea of a nation-state rather than a sect. This is a model wherein Sunnis, Alawis, Christians, Druze, Kurds, Shias, and atheists are all citizens in a deeply flawed, corrupt, and — yes — repressive system in need of improvement but not in need of destruction. The Syrian state has clearly become progressively more brutal as the civil war has dragged on. Still, the regime is not sectarian in the way most in the West seem to think. It is also not purely secular in that it encourages religion (a bit too much) and allows religion to influence the personal status laws of its various sects.

The regime has always felt insecure vis-à-vis its conservative Sunni population, and it has gone out of its way to placate this group over the years by building mosques and Quranic memorization institutes across the country. But denying that the regime is sectarian is not a defense of the regime’s moral choices. Rather, it just shows that it commits mass murder and torture for other reasons, such as the protection and holding together of what is left of the state. This is not an apology for the massive and well-documented human rights violations committed by the Syrian government throughout the course of this war. But until 2011, it offered a society where different religious groups and ethnicities lived together, not in perfect harmony, but at peace. If you do not believe me, look at the millions who have fled from insurgent-held areas to government-held areas and have been received and treated just like any other citizens.

This is far preferable to the sectarian model advanced by much of the Syrian armed opposition, which seeks to create something that will lead ultimately to, at worst, a jihadist caliphate and, at best, a toxic and repressive state in the mold of Saudi Arabia. As I noted in my previous article, the Syrian government has unleashed desperate levels of brutality, using collective punishment, indiscriminate attacks on insurgent-held areas, and harsh siege tactics. Many thousands have died in the regime’s prisons, including the innocent. Likewise, the insurgency has slaughtered many thousands of innocents and participated in the destruction of Syria. This legacy of crimes committed by all will hopefully be dealt with, but all responsible parties should view ending this conflict as the first priority.

In Iraq, there exists a state that should be supported over the claims of Sunni rejectionists who still think they can reestablish Sunni dominance in Iraq. The West should have learned from Iraq, Libya, Egypt, and now Yemen how disastrous regime change is. Better instead to promote a gradual evolution into something better by abandoning the disastrous (and failed) regime change policy and supporting decentralization, as called for by Phil Gordon.

What Drives Disorder?

It is wrong to listen to those who say that insurgents will not stop fighting as long as Assad is in power. Many have stopped already, many cooperate tacitly or overtly, and there are many discussions about ceasefires taking place inside and outside Syria.

It is often claimed that Assad “is a greater magnet for global jihad than U.S. forces were in Iraq at the height of the insurgency.” Assad inherited the same enemy the United States faced in Iraq. The primary recruiter for extremists is the war, the power vacuum created by war, the chaos and despair resulting from it, and the opportunity jihadists see to kill Shias, Alawites, secular apostate Sunnis, Christians, and Western armies gathering for what they view as the final battle before judgment day. Assad is barely mentioned in ISIL propaganda. He is too small for them. They want something much larger, as do the other Salafi jihadi groups operating in the region. It is naive to think that if Assad is simply replaced with somebody else the West finds suitable that the jihadis will be satisfied. Moreover, Assad (just like Maliki) is not in Yemen, Libya, the Sinai, or Afghanistan, and, yet, the Islamic State is growing in all those places.

Many Sunni majority countries in the Middle East and elsewhere are also skeptical of regime change in Syria. Even Turkey, which has allowed jihadists to freely use its territory for much of the war, is slowly changing its policy on regime change in Syria. So those who worry about alienating the so-called Sunni world are really only talking about alienating the Saudis — they just won’t admit it. Saudi Arabia is a more mature version of ISIL, so why should they be placated to defeat anyone?

Regime change or further weakening the Syrian army creates more space for ISIL and similar groups. It grants a victory to the Sunni sectarian forces in the region and leads to state collapse in the remaining stable areas of Syria where most people live.

By pitting moderate Sunnis against extremist Sunnis, the United States merely encourages the sectarian approach. The answer to sectarianism is non-sectarianism, not better sectarianism. If you are looking for a Sunni narrative, you are always playing into the hands of the Sunni hardliners. This does not mean the answer is the Syrian regime in its past or current forms. Opposing sectarian movements does not necessarily mean supporting authoritarian secular states. But functioning states, even imperfect and repressive ones, are preferable to collapsed states or jihadist proto-states.

Westerners are outsiders to this civil war, even if they helped sustain it. For the West, this is not an existential threat, but it is for many of those who live in the Middle East. Those in the region who are threatened by ISIL feel as though beyond the walls of their safe havens there is a horde of zombies waiting to eat their women and children. They might feel that if there is not a cost, in a social sense, paid by those communities who embraced ISIL, then those communities will not have been defeated or learned their lesson. Then, they worry another generation of Sunni extremists will just wait for another chance to take the knives out again. There is an anthropological logic to violence. This is a civil war, inherently between and within communities. It is not merely two armies confronting each other on a battlefield and adhering to the Laws of War. In the eyes of the Syrian and Iraqi states, it is a war on those who welcomed al-Qaeda and then ISIL into their midst.

There is no mechanical link between showing benevolence to formerly pro-ISIL communities and to their not radicalizing in the future. Islamic culture today is globalized, courtesy Saudi funding and modern communications. Many Iraqi Sunnis previously embraced al-Qaeda, only to then embrace the even more virulent ISIL. Future generations should remember that this choice garnered consequences for atrocities, such as the Bunafer tribesmen engaging in the Speicher massacre of Shia soldiers in Iraq. There is a symbolism in a Shia PMF fighter marching into Tikrit, making it clear to Sunni chauvinists that they cannot be the masters over Shia serfs. Yet too severe a punishment, or an unjust one, can indeed leave people with nothing to resort to but violence.

There is little good Washington can do, but it can still inflict a great deal of harm, even if it is motivated by the best of intentions. In The Great Partition, the British historian Yasmin Khan asserted that the partition of India and Pakistan, which killed over one million and displaced many millions, “stands testament to the follies of empire, which ruptures community evolution, distorts historical trajectories and forces violent state formation from societies that would otherwise have taken different—and unknowable—paths.” The same lessons can be learned in Iraq, Libya, and the clumsy international intervention in Syria. It is time that the West started to mind its own business rather than address the failure of the last intervention with the same tools that caused the disaster in the first place. At most, the West can try to help manage or channel the evolution of the region or contain some of its worst side effects.

The order in modern Europe is a result of bloody processes that saw winners and losers emerging and the losers accepting the new order. ISIL’s arrival has expedited this historic process in the Middle East. It has helped organize and mobilize Iraq Shias and connect them to the rest of the world, while the disastrous decision of many Sunnis to embrace movements such as ISIL has caused many of their communities to suffer irreparable damage and dislocation.

Perhaps the Middle East is going through a similar process that will lead to a new more stable order after these terrible wars are over. This period of great flux offers creative opportunities. While some analysts have called for breaking up Syria and Iraq into smaller ethnic and sectarian entities, this would lead to more displacement and fighting, as it did in the Balkans over the course of over a century. Instead of promoting the worst fissiparous tendencies in the region, the solution might be creating greater unity

The American asteroid that hit the Middle East in 2003 shattered the old order. Those tectonic plates are still shifting. The result will not be an end to the old borders, as many have predicted or even suggested as policy. It will also not be the total collapse of states. The evolving new order will retain the formal borders, but central states will not have full control or sovereignty over all their territory. They will rely on loose and shifting alliances with local power brokers, and they will govern in a less centralized way. Accepting this and supporting looser federal arrangements may be the best path forward to reduce fears, heal wounds, and bring about stability.

Cyrus Malik is a pen name for a security consultant to the humanitarian community in the Levant and Iraq.

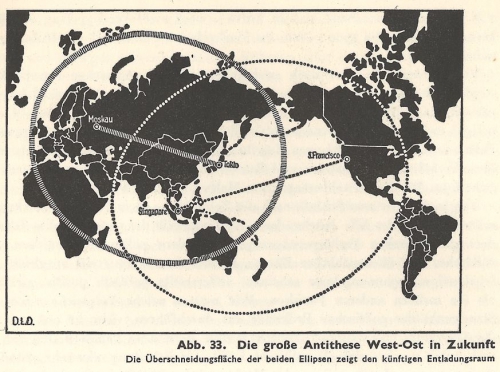

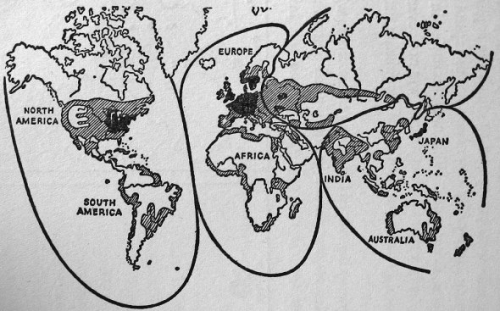

Alla ripresa dell’insegnamento la gioventù tedesca del dopoguerra sembrava priva soprattutto della capacità di visioni grandiose (di dimensioni continentali!) e della conoscenza delle condizioni di vita di altri popoli, in particolare di quelli oceanici. Tagliata fuori dal vivificante respiro del mare e privata dei suoi rapporti ultramarini, era portatrice di una visione del mondo di ristrettezza continentale, era divenuta meschina e si perdeva in una quantità di tensioni di poco conto, come dimostrava anche la frammentazione in 36 partiti e in numerose leghe. La sua conoscenza di ampie realtà condizionate dal mare, come quelle dell’impero britannico, degli Stati Uniti d’America, del Giappone e dell’Impero olandese delle Indie Orientali, era ancora più esigua di quella che aveva del Medio e Vicino Oriente, dell’Eurasia e dell’Unione Sovietica.

Alla ripresa dell’insegnamento la gioventù tedesca del dopoguerra sembrava priva soprattutto della capacità di visioni grandiose (di dimensioni continentali!) e della conoscenza delle condizioni di vita di altri popoli, in particolare di quelli oceanici. Tagliata fuori dal vivificante respiro del mare e privata dei suoi rapporti ultramarini, era portatrice di una visione del mondo di ristrettezza continentale, era divenuta meschina e si perdeva in una quantità di tensioni di poco conto, come dimostrava anche la frammentazione in 36 partiti e in numerose leghe. La sua conoscenza di ampie realtà condizionate dal mare, come quelle dell’impero britannico, degli Stati Uniti d’America, del Giappone e dell’Impero olandese delle Indie Orientali, era ancora più esigua di quella che aveva del Medio e Vicino Oriente, dell’Eurasia e dell’Unione Sovietica.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg