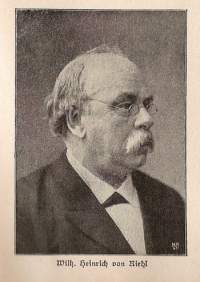

Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl (6 May 1823 – 16 November 1897) was a German journalist, novelist and folklorist.

Riehl was born in Biebrich in the Duchy of Nassau and died in Munich.

Riehl’s writings became normative for a large body of Volkish thought. He constructed a more completely integrated Volkish view of man and society as they related to nature, history, and landscape. He was the writer of the famous ‘Land und Leute’ (Places and People), written in 1857-63, which discussed the organic nature of a Volk which he claimed could only be attained if it fused with the native landscape.

“Personally Riehl applied the bulk of his labors to the two contiguous fields of Folklore and Art History. Folklore (Volkskunde) is here taken in his own definition, namely, as the science which uncovers the recondite causal relations between all perceptible manifestations of a nation’s life and its physical and historical environment. Riehl never lost sight, in any of his distinctions, of that inalienable affinity between land and people; the solidarity of a nation, its very right of existing as a political entity, he derived from homogeneity as to origin, language, custom, habitat.”

Otto Heller – The German Classics of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

“Riehl’s writings became normative for a large body of Volkish thought…he constructed a more completely integrated Volkish view of man and society as they related to nature, history, and landscape….in his famous Land und Leute (Land and People), written in 1857-63,” which “discussed the organic nature of a Volk which he claimed could only be attained if it fused with the native landscape….Riehl rejected all artificiality and defined modernity as a nature contrived by man and thus devoid of that genuineness to which living nature alone gives meaning…Riehl pointed to the newly developing urban centers as the cause of social unrest and the democratic upsurge of 1848 in Hessia”….for many “subsequent Volkish thinkers, only nature was genuine.”

“Riehl desired a hierarchical society that patterned after the medieval estates. In Die bürgerliche Gesellschaft(Bourgeois Society) he accused those of Capitalist interest of “disturbing ancient customs and thus destroying the historicity of the Volk.”

George Mosse

“We must save the sacred forest, not only so that our ovens do not become cold in winter, but also so that the pulse of life of the people continues to beat warm and joyfully, so that Germany remains German.”

“In the contrast between the forest and the field is manifest the most simple and natural preparatory stage of the multiformity and variety of German social life, that richness of peculiar national characteristics in which lies concealed the tenacious rejuvenating power of our nation.”

“In our woodland villages—and whoever has wandered through the German mountains knows that there are still many genuine woodland villages in the German Fatherland—the remains of primitive civilization are still preserved to our national life, not only in their shadiness but also in their fresh and natural splendor. Not only the woodland, but likewise the sand dunes, the moors, the heath, the tracts of rock and glacier, all wildernesses and desert wastes, are a necessary supplement to the cultivated field lands. Let us rejoice that there is still so much wilderness left in Germany. In order for a nation to develop its power it must embrace at the same time the most varied phases of evolution. A nation over-refined by culture and satiated with prosperity is a dead nation, for whom nothing remains but, like Sardanapalus, to burn itself up together with all its magnificence. The blasé city man, the fat farmer of the rich corn-land, may be the men of the present; but the poverty-stricken peasant of the moors, the rough, hardy peasant of the forests, the lonely, self-reliant Alpine shepherd, full of legends and songs—these are the men of the future. Civil society is founded on the doctrine of the natural inequality of mankind. Indeed, in this inequality of talents and of callings is rooted the highest glory of society, for it is the source of its inexhaustible vital energy.”

Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl – Field and Forest

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les commentaires sont fermés.