Following the publication of my review of Yukio Mishima’s guide to Hagakure, Andrew Joyce, a fellow contributor to The Occidental Observer, has published a thorough and highly critical account of the Japanese writer’s life. I was going to draw attention to Joyce’s piece, which has already been republished by The Unz Review.

Here is a partial summary of Joyce’s points:

- Despite being married, Mishima had a completely degenerate gay sex life and neglected his children.

- Mishima’s right-wing politics were adopted late and were vague, insincere, and ultimately a kind of posing.

- Mishima’s spectacular last day, far from being a serious traditionalist/militarist political statement, was merely the ultimate enactment of his perverse and self-destructive psycho-sexual fantasies.

Joyce concludes:

Members of the Dissident Right with an interest in Japanese culture are encouraged to take up one or more of the martial arts, to look into aspects of Zen, or to review the works of some of the other twentieth-century Japanese authors mentioned here. Such endeavors will bear better fruit. Above all, however, there is no comparison with spending time researching the lives of one’s own co-ethnic heroes and one’s own culture. As Europeans, we are so spoiled for choice we needn’t waste time with the rejected, outcast, and badly damaged members of other groups.

I invite you to read Joyce’s piece in full.

All this having been said, I still encourage people to watch Paul Schrader’s film on Mishima and to read Mishima’s guide to Hagakure (or better yet, Hagakure itself). I will myself, when time permits, try to read Mishima’s later more political fiction (e.g. Runaway Horses) and other nonfiction. A work of art is no less compelling, a logical argument no less persuasive, whatever the author’s personal deficiencies or proclivities.

All this having been said, I still encourage people to watch Paul Schrader’s film on Mishima and to read Mishima’s guide to Hagakure (or better yet, Hagakure itself). I will myself, when time permits, try to read Mishima’s later more political fiction (e.g. Runaway Horses) and other nonfiction. A work of art is no less compelling, a logical argument no less persuasive, whatever the author’s personal deficiencies or proclivities.

On TOO, Joyce’s piece has received an informative, nuanced, and detailed comment from a certain Ryuji Tsukazaki, who seems to be fluent in Japanese. I reproduce Tsukazaki’s comment in full:

This essay probably needed to be written. But to any readers who think it seems a little unfair aggressively negative – it is.

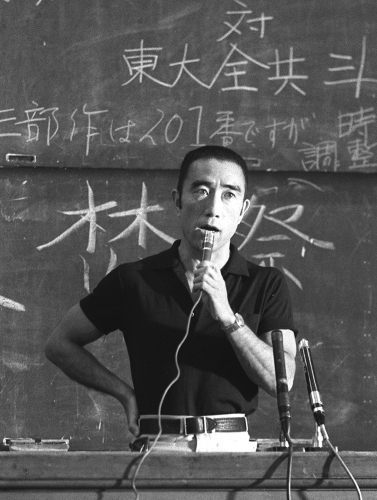

The assertion that Mishima “seems hardly political at all” is just silly. It’s true that rightists who read his fiction often find it disappointing. Taken as a whole, his literary oeuvre certainly contains more weird homoeroticism than it does right-wing nationalism. But Mishima also wrote a lot of non-fiction, which was mostly explicitly political. Some titles that come to mind right away are “In Defense of Culture”, “For Young Samurai”, and “Lectures on Immorality”. (These are all my unofficial titles. I don’t think any of them are officially translated.) They are treatments of Japanese political culture, identity, and morality in the post-war era. It’s impossible to tie them to gayness or sadomasochism; they’re obviously sincere. Mishima also took part in debates on campuses during the late 60s student riots (he wrote essays about them too).

Despite the assertion that he became political “in the 60s”, perhaps because he was afraid of growing old – his most explicitly political work of fiction, Patriotism, came out in 1961, halfway through his career, when he was 35. “The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea”, another major midcareer work of fiction, isn’t explicitly political, but very clearly touches on themes of authentic masculinity, loyalty, and patrimony.

“he argued that Japanese right-wingers “did not have to have a systematised worldview,”” I don’t know the context of this quote, or what he said in the original, but it’s actually hard to argue with – especially because Japanese right-wingers have never HAD a systematised worldview. The desire for metaphysical, moral, and/or ideological formal systemization is very European. Prewar Japanese historical figures will often be described as fighting for democracy and human rights in one context and as fierce right-wing militarists in others (Kita Ikki and Toyama Mitsuru come to mind). If Mishima’s assertion bothers you, don’t sweat it – it’s not about you, it’s about the Japanese.

“Mishima is a pale shadow of ultra-nationalist literary contemporaries like Shūmei Ōkawa…” I have to niggle about this. Shumei Okawa is neither literary nor contemporary. He was active in the prewar era only, and I’m unaware of any fiction he wrote. The others you mentioned may be superior to Mishima as ultranationalists but not as men of letters.

As I said, this essay did need to be written – it’s hard to look deeply into Mishima and feel comfortable with Western rightist idolization of him. He was nothing so simple and appealing as le based Japanese samurai man. And it’s true that his life and work was driven greatly by his sexuality. It’s untrue that he was politically insincere or shallow. He was nothing like a European fascist, and he couldn’t be called a traditionalist. Nonetheless, he prioritized the authentically Japanese over the modern or Western; he prioritized the healthy over the sick, and the strong over the weak; and the masculine over the feminine or androgynous. He brought up these themes repeatedly in his writings, fiction and nonfiction.

“Mishima was a profoundly unhealthy and inorganic individual” – this sentence stuck out to me as undeniably true. And I think it’s also true of many other important writers and thinkers. When Nietzsche wrote that wisdom appears on earth as a raven attracted by the scent of carrion, he was doing nothing so simple as attacking wisdom. Blond Beasts rarely write groundbreaking philosophy or provocative fiction; conflicted people who hate themselves and/or the world they were born into do that more. (Nietzsche himself could be described as an unhealthy and inorganic individual, though not to Mishima’s level.) Mishima’s disturbed sexuality and weak, sick childhood were catalysts that forced him to really grapple with masculinity and identity on a personal and intellectual level. When we read about him we should be aware that he was not an ubermensch and that he was a pervert. I don’t see that as reason to dismiss him.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les commentaires sont fermés.