By Srdja TRIFKOVIC (USA)

Ex: http://orientalreview.org

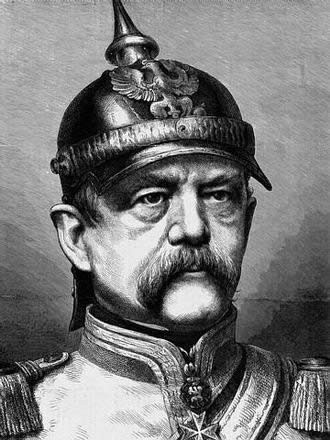

In an interview for the German news magazine Zuerst! (April 2015) Srdja Trifkovic considers the significance of Otto von Bismarck’s legacy, 200 years after his birth.

Dr. Trifkovic, how would Bismarck react if he could see today’s map of Europe?

Trifkovic: He would be initially shocked that the German eastern border now runs along the Oder and Neisse rivers. Otto von Bismarck was a true Prussian. In his view, cities such as Königsberg, Danzig or Breslau were more properly “German” than those in the Rhineland. His first impression therefore would be that Germany has “shifted” to the West, and that an important social and cultural aspect of his Germany has been lost. Once he’d overcome this initial shock, he would look at the map of Europe again in more detail. The considerable distance between Germany and Russia would probably amaze him. What in Bismarck’s time was the border between Germany and Russia is now a “Greater Poland” which did not exist at his time. And former provinces of the Russian Empire are now independent states: the three Baltic republics, Belarus and Ukraine. Bismarck would probably see this as an unwelcome “buffer zone” between Germany and Russia. He had always placed a great emphasis on a strong German-Russian alliance and would no doubt wonder how all this could happen. He would probably consider how to bring back to life such a continental partnership today. That would be a diplomatic challenge worthy of him: how to forge an alliance between Berlin and Moscow without the agitated smaller states in-between throwing their spanners into the works.

What would he advise Angela Merkel?

Trifkovic: He would probably tell her that even if you cannot have a close alliance with Russia, at least you should seek a better balance, i.e. more equidistant relations with Washington on the one hand and Moscow on the other. The concept of the Three Emperors’ League of 1881 is hardly possible today, but there are other options.

Security and the war in Ukraine would focus Bismarck’s attention…

Trifkovic: Merkel has adopted a very biased position on Ukraine, which Bismarck would have never done. He was always trying to cover his country from all flanks. In Ukraine we can clearly observe a crisis scenario made in Washington. Bismarck’s policy in the case of modern Ukraine would be for Berlin to act as a trusted and neutral arbiter of European politics, and not just as a trans-Atlantic outpost.

You said earlier that Germany since the time of Bismarck has shifted to the west. Do you mean this not only geographically?

Trifkovic: Even as a young man, as the Prussian envoy to the Bundestag in Frankfurt, Bismarck detested the predominantly western German liberals. At the same time, he later endeavored to ensure that Catholic Austria would be kept away from the nascent German Empire. Even at an early age we could discern Bismarck’s idea of Germany: a continental central power without strong Catholic elements and liberal ideas. He also knew that such a central European power must always be wary of the possibility of encirclement. Bismarck knew that he had to prevent France and Russia becoming partners.

At all times the rapport with Russia appeared more important than that with France…

Trifkovic: Here is an oddity in Bismarck’s policy. After the 1870-71 war against France, the newly created German Empire annexed Alsace and Lorraine and thus ensured that there would be permanent tensions with a revanchist France. In real-political terms it should have been clear that any benefits of Alsace-Lorraine’s annexation would be outweighed by the disadvantages. French irredentism made her permanently inimical to Germany. No political overture to Paris was possible. The entire policy of the Third French Republic (1870-1940) was subsequently characterized by deep anti-German resentment.

As an American with Serb roots, you know East and West alike. Are there some differences in their approach to Otto von Bismarck?

Trifkovic: Apart from a few individuals in the scientific community, I am sorry to say that Otto von Bismarck is not adequately evaluated either in the West or in the East. On both sides, you will often encounter a flawed caricature of Bismarck as a bloodthirsty warmonger and nationalist who was ruthlessly pursuing Germany’s unification and whose path was paved with corpses. Nothing is further from the truth. The three wars that preceded unification were limited armed conflicts with clear and limited aims. Bismarck ended two of those wars without unnecessarily humiliating the defeated foe; France was an exception. The war against Austria in 1866 in particular showed that Bismarck’s only concern was to secure Prussia’s supremacy in German affairs. Only a few years later he concluded an alliance with Austria-Hungary. Let me repeat: Bismarck was not a brutal warmonger; he was a brilliant political realist who quickly grasped his advantages and his opponents’ weaknesses. Therein lies an irony that today’s moralists find difficult to explain: Bismarck was a cold calculator and his decisions were rarely subjected to ethical criteria – but the result of his Realpolitik was a relatively stable German state which under Bismarck’s chancellorship managed Europe’s adjustment to its rise without armed conflicts. Between 1871 and 1890, the German Empire was on the whole a stabilizing factor in Europe. During the Berlin Congress to end the Balkan crisis in 1878, Bismarck effectively presented himself as an honest broker, respected by all of Europe. However, with Bismarck’s departure in 1890, this period of the relaxation of European tensions and Germany’s stabilizing influence was over.

What changed after 1890 for Europe?

Trifkovic: After Bismarck there was no longer a steadfastly reliable Chancellor and the German policy lost its sureness of touch. Suddenly the neurotic spirit of the young Emperor, Wilhelm II, started prevailing, a feverish “we have-to-do-something” atmosphere. The massive naval program was initiated, while the Reinsurance Treaty with Russia was not renewed – and it was the cornerstone of Bismarck’s scenario to prevent a war in Europe. Initially the Czarist Empire urged the renewal of the bilateral agreement with Berlin. The Kaiser took the view that the Reich could be better protected by its own military buildup than through alliances. And suddenly, Bismarck’s nightmare came true. Since Russia abruptly found herself with no international allies, and the German-Russian relations cooled more and more, it approached France and arranged the military convention of 1892. In 1894 a firm alliance was signed. It was not ideological. The liberal, Masonic, secular and republican France was allied with the Orthodox Christian, deeply conservative, autocratic Russian Empire. And Germany was in the middle. Bismarck always dreaded this sort of two-front alliance, which laid the foundations of the blocs of belligerent powers in World War I. You can see some current parallels in the policy shift of 1890.

In what way?

Trifkovic: The often neurotic policy of Berlin after Bismarck’s dismissal reminds one of the aggressive style of the likes of Victoria Nuland and John McCain today. Looking at Germany from 1890 to 1914, one sees striking parallels with today’s U.S. neoconservatives. The obsession with Russia as the enemy is one similarity. After Bismarck’s dismissal, Russia was depicted in the media of the German Empire in darkest colors, as backward, aggressive and dangerous. If we take today’s Western mainstream media – including those in Germany – this image has just been reinforced: the dangerous, backward, and aggressive Putin Empire.

Bismarck was not a German Neocon?

Trifkovic: (laughs) No, he was the exact opposite! He was not a dreamer, nor an ideologue. He did not want to go out into the world to bring Germanic blessings to others, if necessary by the force of arms. Bismarck was always a down-to-earth Prussian landowner. While Britain as a naval power opened up trading posts and founded colonies all over the world, and British garrisons were stationed all over in India or Africa, Bismarck’s Germany was created as a classic land-based continental power. I would even suggest that Bismarck himself had an aversion to the sea. Very reluctantly he was persuaded in the 1880’s to agree to the acquisition of the first protectorates for the German Reich. On the whole, Germany’s colonial program was economically questionable. What Germany was left with in the 1880’s was what the other major colonial powers had left behind, especially the United Kingdom. Bismarck knew that, and he saw that all the important straits and strategic points, such as the Cape of Good Hope, were under British control. In Germany the colonial question was mostly about “prestige” and “credibility” – and Bismarck the master politician had no time at all for such reasoning.

Bismarck also had a clear position on the Balkans. In 1876, he said in a speech that the German Empire in the Balkans had no interest “which would be worth the healthy bones of a single Pomeranian grenadier.” This seems to have changed, however: Today German soldiers are in Kosovo, the Federal Republic of Germany was the first country to recognize the independence of Slovenia and Croatia from Yugoslavia in 1991…

Trifkovic: Otto von Bismarck was always weary of tying Germany’s fate to that of Austria-Hungary. His decision to steer clear of the conflicts in the Balkans was sound. After Bismarck’s dismissal Germany saw the rise of anti-Russian and anti-Serbian propagandistic discourse which emulated that in Vienna. Incidentally, there is another quote by Bismarck which was truly prophetic. “Europe today is a powder keg and the leaders are like men smoking in an arsenal,” he warned. “A single spark will set off an explosion that will consume us all. I cannot tell you when that explosion will occur, but I can tell you where. Some damned foolish thing in the Balkans will set it off.” In relation to Serbia there are parallels to the current situation in Europe. In 1903 a dynastic change in Belgrade ended Austria-Hungary’s previous decisive influence in the small neighboring country. The house of Karadjordjevic oriented Serbia to the great Slav brother, to Russia. Vienna tried to stop that by subjecting Serbia to economic and political pressure. But out of this so-called “tariff war” Serbia actually emerged strengthened. We recognize the parallels to Russia today: one can compare the Vienna tariff war against Belgrade with the sanctions against Russia. Sanctions force a country to diversify its economy, thus making it more resistant. In Serbia it worked well a hundred years ago, in Russia it may work now. When Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908, there was a serious emergency and only Germany taking sides with Vienna ended the Bosnian crisis. In the end Germany picked up the tab: After the outbreak of World War I Austrian-Hungarian troops failed to defeat Serbia. They needed military assistance from Germany. Prussian Field Marshal August von Mackensen finally defeated Serbia, and proved to be a truly chivalrous opponent: “In the Serbs I have encountered the bravest soldiers of the Balkans,” he wrote in his diary. Later, in 1916, Mackensen erected a monument to the fallen Serbs in Belgrade with the inscription “Here lie the Serbian heroes.”

When we in Germany think of Bismarck today, we come back time and over again to the relationship with Russia … [Trifkovic: Indeed!] … Is it possible to summarize the relations as follows: If Germany and Russia get along, it is a blessing for Europe; if we go to war, the whole continent lies in ruins?

Trifkovic: The only ones who are chronically terrified of a German-Russian understanding are invariably the maritime powers. In the 19th century the British tried to prevent the rise of an emerging superpower on the continent, such as a German-Russian alliance. Looking at the British Empire and its naval bases, one is struck by how the Eurasian heartland was effectively surrounded. Halford Mackinder formulated it memorably: “Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland; who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island; who rules the World-Island commands the world.” Dutch-American geo-strategist Nicholas J. Spykman developed Mackinder’s theory further. It is the “Rimland” – which surrounds the heartland – that is the key to controlling the land mass. Spykman is considered as a forerunner of the U.S. containment policy after the war.

Spykman was focused especially on the communist Soviet Union, not so much on Germany…

Trifkovic: He was concerned with controlling the “Heartland” quite independently of the dominant land power’s ideology. Spykman wrote in early 1943 that the Soviet Union from the Urals to the North Sea, from an American perspective, was no less unpleasant than Germany from the North Sea to the Urals. A continental power in Eurasia had to be curtailed or at least fragmented – that is exactly the continuity of the global maritime power’s strategy to this day.

On sanctions against Russia, and U.S.-EU disputes, Germany is in the middle. What would Chancellor Bismarck do today?

Trifkovic: He would swiftly end the sanctions regime against Russia because he’d see that Germany was paying a steep price for no tangible benefit. He would also seek to reduce the excessive U.S. influence on German policymaking. But Europe does not necessarily need a new Bismarck: as recently as 50 years ago we had several European politicians of stature and integrity. People like Charles de Gaulle or Konrad Adenauer had more character and substance than any of the current EU politicians. Europe in its current situation is in great need of them.

Source: Chronicles

Was de geschiedenis van Rome een voorafspiegeling van die van het Duitsland waarin Theodor Mommsen leefde en stierf? Toen hij in 1817 in het Noord-Duitse Garding het levenslicht zag, vormde Duitsland nog een confederatie van 38 kleine en middelgrote staten. Maar toen hij in 1903 overleed, was Duitsland al een Keizerrijk en een geduchte Europese grootmacht met grootste ambities op het wereldtoneel. Als journalist, professor en later lid van het Pruisische parlement zou de jonge Mommsen ijveren voor een vrij en verenigd Duitsland. In 1849 had hij in Dresden zelfs de barricades van de (mislukte) revolutie beklommen, wat tot zijn ontslag als professor aan de universiteit van Leipzig leidde.

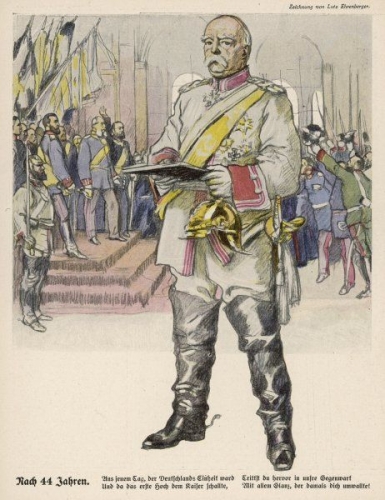

Was de geschiedenis van Rome een voorafspiegeling van die van het Duitsland waarin Theodor Mommsen leefde en stierf? Toen hij in 1817 in het Noord-Duitse Garding het levenslicht zag, vormde Duitsland nog een confederatie van 38 kleine en middelgrote staten. Maar toen hij in 1903 overleed, was Duitsland al een Keizerrijk en een geduchte Europese grootmacht met grootste ambities op het wereldtoneel. Als journalist, professor en later lid van het Pruisische parlement zou de jonge Mommsen ijveren voor een vrij en verenigd Duitsland. In 1849 had hij in Dresden zelfs de barricades van de (mislukte) revolutie beklommen, wat tot zijn ontslag als professor aan de universiteit van Leipzig leidde. Zijn die harde woorden, die harde oordelen van Mommsen over Bismarck en het door hem verenigde Duitsland wel gerechtvaardigd? Het Duitse keizerrijk (1871-1918) was beter dan zijn reputatie. Wetenschappen en kunsten bloeiden, de ene na de andere universiteit werd opgericht, duizenden kranten- en tijdschriftentitels verschenen, iedere (weliswaar mannelijke) burger genoot stemrecht en waar in Groot-Brittannië 70% van de gronden in handen van de adel was, gold dat in Duitsland voor ‘slechts’ 30%. Had Bismarck niet ook met zijn ‘Sozialgesetze’ de kiemen gelegd voor de sociale zekerheid? En was de ‘Schutzzoll’ (de ‘beschermende tol’) niet revolutionair, zoals Paul Lensch (1873-1926), journalist en sociaaldemocratisch lid van de Reichstag, stelde in zijn boek ‘Drei Jahre Weltrevolution’ (Leipzig 1917)? Deze tol zou immers de opkomende Duitse industrie tegen de Britse concurrentie beschermd en uiteindelijk naar haar dominantie op de wereldmarkt geleid hebben.

Zijn die harde woorden, die harde oordelen van Mommsen over Bismarck en het door hem verenigde Duitsland wel gerechtvaardigd? Het Duitse keizerrijk (1871-1918) was beter dan zijn reputatie. Wetenschappen en kunsten bloeiden, de ene na de andere universiteit werd opgericht, duizenden kranten- en tijdschriftentitels verschenen, iedere (weliswaar mannelijke) burger genoot stemrecht en waar in Groot-Brittannië 70% van de gronden in handen van de adel was, gold dat in Duitsland voor ‘slechts’ 30%. Had Bismarck niet ook met zijn ‘Sozialgesetze’ de kiemen gelegd voor de sociale zekerheid? En was de ‘Schutzzoll’ (de ‘beschermende tol’) niet revolutionair, zoals Paul Lensch (1873-1926), journalist en sociaaldemocratisch lid van de Reichstag, stelde in zijn boek ‘Drei Jahre Weltrevolution’ (Leipzig 1917)? Deze tol zou immers de opkomende Duitse industrie tegen de Britse concurrentie beschermd en uiteindelijk naar haar dominantie op de wereldmarkt geleid hebben.

Dans les cercles piétistes, il a rencontré sa femme et quelques futurs collaborateurs. Parmi eux se trouvait von Roon, qui l'a introduit dans le cercle du futur Wilhelm I. Son éducation politique et culturelle a eu un impact sur sa vie. Son éducation politique et culturelle culmine dans sa fréquentation du cercle conservateur animé par les frères von Gerlach. Il acquiert une expérience administrative au niveau municipal et provincial jusqu'à ce que, après l'accession de Wilhelm Ier au trône en 1862, il soit appelé à la Diète de Francfort en tant que représentant du souverain. Ses discours étaient caractérisés par un esprit anti-révolutionnaire et démontraient ses qualités oratoires incontestables, comme le montre le livre que nous présentons ici. L'art oratoire de Bismarck, tout en montrant en maints endroits la vaste culture du chancelier, avec des références à Goethe, Lessing, Schiller, Heine, son auteur préféré plus que tout autre, était direct: " il était fondé sur la franchise et l'attaque [...] au-delà de toute pratique rhétorique" (p. III). Il a toujours été conscient du lien entre les choix de politique intérieure et étrangère, en raison de son long séjour en tant qu'ambassadeur à Saint-Pétersbourg et, pour une période plus courte, à Paris. Il se trouvait dans la capitale française lorsqu'il a été rappelé par le nouveau monarque, qui lui a confié la chancellerie.

Dans les cercles piétistes, il a rencontré sa femme et quelques futurs collaborateurs. Parmi eux se trouvait von Roon, qui l'a introduit dans le cercle du futur Wilhelm I. Son éducation politique et culturelle a eu un impact sur sa vie. Son éducation politique et culturelle culmine dans sa fréquentation du cercle conservateur animé par les frères von Gerlach. Il acquiert une expérience administrative au niveau municipal et provincial jusqu'à ce que, après l'accession de Wilhelm Ier au trône en 1862, il soit appelé à la Diète de Francfort en tant que représentant du souverain. Ses discours étaient caractérisés par un esprit anti-révolutionnaire et démontraient ses qualités oratoires incontestables, comme le montre le livre que nous présentons ici. L'art oratoire de Bismarck, tout en montrant en maints endroits la vaste culture du chancelier, avec des références à Goethe, Lessing, Schiller, Heine, son auteur préféré plus que tout autre, était direct: " il était fondé sur la franchise et l'attaque [...] au-delà de toute pratique rhétorique" (p. III). Il a toujours été conscient du lien entre les choix de politique intérieure et étrangère, en raison de son long séjour en tant qu'ambassadeur à Saint-Pétersbourg et, pour une période plus courte, à Paris. Il se trouvait dans la capitale française lorsqu'il a été rappelé par le nouveau monarque, qui lui a confié la chancellerie.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Am 6. August 1862 begegnet Otto von Bismarck in Biarritz dem russischen Fürsten Nikolai Orloff und dessen Gattin Katharina, geborene Trubezkaja. Der künftige „Eiserne Kanzler“ verknallt sich auf der Stelle in die 22-jährige Blondine. Er selbst ist bereits 47.

Am 6. August 1862 begegnet Otto von Bismarck in Biarritz dem russischen Fürsten Nikolai Orloff und dessen Gattin Katharina, geborene Trubezkaja. Der künftige „Eiserne Kanzler“ verknallt sich auf der Stelle in die 22-jährige Blondine. Er selbst ist bereits 47. Der heute 74-jährige Topol (Bild), der in den 70er-Jahren nach Europa und anschließend in die USA ausgewandert war, sich später aber auch in seiner postsowjetischen Heimat einen Namen machte, hat nämlich für Erotik einiges übrig. Mit seinen Büchern „Russland im Bett“, „Neues Russland im Bett“, „Die unschuldige Nastja, oder: Die ersten 100 Männer“, „Ich will dein Mädchen“ etc. sorgte er dafür, dass seine Leserschaft in jedem neuen Werk von ihm auf Prickelndes wartet. In „Bismarck“ kommt sie – wenn auch nicht mehr so ausgiebig wie früher – auf ihre Kosten. „Ich kann mich noch erinnern, wie das funktioniert“, gesteht der Autor schmunzelnd.

Der heute 74-jährige Topol (Bild), der in den 70er-Jahren nach Europa und anschließend in die USA ausgewandert war, sich später aber auch in seiner postsowjetischen Heimat einen Namen machte, hat nämlich für Erotik einiges übrig. Mit seinen Büchern „Russland im Bett“, „Neues Russland im Bett“, „Die unschuldige Nastja, oder: Die ersten 100 Männer“, „Ich will dein Mädchen“ etc. sorgte er dafür, dass seine Leserschaft in jedem neuen Werk von ihm auf Prickelndes wartet. In „Bismarck“ kommt sie – wenn auch nicht mehr so ausgiebig wie früher – auf ihre Kosten. „Ich kann mich noch erinnern, wie das funktioniert“, gesteht der Autor schmunzelnd.  Katharina stirbt aber noch viel früher als er mit 35. Als Bismarck das erfährt, verfällt er für sieben Jahre in Depression. Inzwischen hat er als Politiker ziemlich alles erreicht, die Liebe seines Lebens ist aber nicht mehr auf dieser Welt. Wozu dann das Ganze?

Katharina stirbt aber noch viel früher als er mit 35. Als Bismarck das erfährt, verfällt er für sieben Jahre in Depression. Inzwischen hat er als Politiker ziemlich alles erreicht, die Liebe seines Lebens ist aber nicht mehr auf dieser Welt. Wozu dann das Ganze?