Editor’s Note:

This is the transcript by V. S. of Richard Spencer’s Vanguard podcast interview of Jonathan Bowden about eugenics, environmentalism, Madison Grant, and Lothrop Stoddard. You can listen to the podcast here [2]. The subtitle is editorial.

Richard Spencer: Hello, everyone, and welcome back to Vanguard! And welcome back as well, Jonathan Bowden!

Jonathan Bowden: Yes, hello! Nice to be here.

RS: Very good. Jonathan, today we’re going to talk about eugenics, Madison Grant, Lothrop Stoddard, and the whole constellation of ideas and thinkers surrounding that subject. Before we jump into the conversation, I think it’s worth mentioning this: we certainly live in an age of partisan vitriol and Left-Right battles, but some of the things that really interest me are not those places where the mainstream Left and Right disagree with one another but where they are in total agreement, where they walk lock-step, and one of those things is the denunciation of eugenics as the most evil movement or at least one of them of the past 200 years. It’s certainly also quite often associated with that other most evil movement of Fascism or National Socialism. I think all of them are in agreement that it is both a pseudo-science, but then it’s also in some ways all too effective and something we need to resist. So, it didn’t work, but then it was all too effective at the same time usually in some of these irrational critiques they have of it.

This is a fascinating opinion, because this is something that has changed dramatically over the past century. It’s hard to find another opinion where you have a 180 degree shift in such a fairly short amount of time. It’s almost as if the Western world converted to Islam and began denouncing Christianity and secularism overnight. Perhaps not that dramatic, but you see my point.

Certainly, something like the National Socialist regime in Germany did have eugenics programs. They were not actually as pronounced as some might believe. They actually modeled a lot of those programs on the eugenics programs found in Sweden and in the state of California. California was probably the ultimate model. You had eugenics being endorsed by university presidents. That is, it was very much endorsed by the elite. They thought this was a good thing and it was also a part of the progressive elite. Eugenics was not a reactionary opinion. It was something that was opposed by the old time religion folks or whom you might call reactionaries. It was something that might even be on the Left in certain contexts. Certainly, with somebody like Lothrop Stoddard, who we’re going to speak about a little bit later, it was a position held by someone who openly thought of himself as a progressive and a modernist. And it also had some popular appeal. Actually, in a talk I gave not too long ago at the H. L. Mencken Club, I showed some pictures that were actually taken by a very good book, a biography of Lothrop Stoddard which was written by a Left-liberal who doesn’t like Stoddard very much but recognizes his importance, but these pictures were of eugenic buildings at the state fair. I believe a famous one was from the Kansas State Fair. They would have a competition for the fittest family, and what they wanted to see was a good genotype. That was a healthy family with all boys and girls looking strong and smart and good-looking parents and things like this. So, eugenics really had a positive value in peoples’ lives. It was something that meant that they were healthy and good and normal and people of quality. Obviously, this has gone through a total reversal.

Certainly, something like the National Socialist regime in Germany did have eugenics programs. They were not actually as pronounced as some might believe. They actually modeled a lot of those programs on the eugenics programs found in Sweden and in the state of California. California was probably the ultimate model. You had eugenics being endorsed by university presidents. That is, it was very much endorsed by the elite. They thought this was a good thing and it was also a part of the progressive elite. Eugenics was not a reactionary opinion. It was something that was opposed by the old time religion folks or whom you might call reactionaries. It was something that might even be on the Left in certain contexts. Certainly, with somebody like Lothrop Stoddard, who we’re going to speak about a little bit later, it was a position held by someone who openly thought of himself as a progressive and a modernist. And it also had some popular appeal. Actually, in a talk I gave not too long ago at the H. L. Mencken Club, I showed some pictures that were actually taken by a very good book, a biography of Lothrop Stoddard which was written by a Left-liberal who doesn’t like Stoddard very much but recognizes his importance, but these pictures were of eugenic buildings at the state fair. I believe a famous one was from the Kansas State Fair. They would have a competition for the fittest family, and what they wanted to see was a good genotype. That was a healthy family with all boys and girls looking strong and smart and good-looking parents and things like this. So, eugenics really had a positive value in peoples’ lives. It was something that meant that they were healthy and good and normal and people of quality. Obviously, this has gone through a total reversal.

Well, Jonathan, I think we should talk about all of these things in detail, but maybe you could pick up on that basic history of eugenics that I’ve just outlined that something that was hegemonic has become unspeakable just over the course of 100 years. Something that was endorsed by presidents and now is associated with crazed lunatics. Maybe just talk a little about that and talk a little bit about why that happened. Do you think it was just the legacy of the Second World War or was there something more involved? So, why don’t you just pick up on that, say, our consciousness of eugenics in the 20th century?

JB: Yes, I think what we have here is the acceptance of and then the rejection of, one then the other, the notion that biology impinges upon social matters to a very considerable degree. From about 1860/1870 through to the 1940s, you had a very pronounced view in all sorts of countries, particularly countries like Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, Denmark, Sweden, Switzerland, and elsewhere — countries you don’t often associate with these sorts of ideas. But eugenic ideas were very pronounced in the policies in these societies and amongst academic and clinical elites.

In some ways, it was progressive biologism. It was the belief that you could act upon that and upon circumstances of lived anthropology as contemporaneously understood, and you could improve the human lot. Just as you could act upon the social and economic sphere from a center-Left perspective to improve mankind’s lot, and from the interventionist conservative’s perspective as well, you could also improve man’s lot biologically.

How this was to be done was a subject of maximal debate, but the idea was that if you bred the strongest children and the tallest children and the fairest children and the most intellectually precocious children who also have pronounced athletic abilities that you would actually begin to create more wholesome human beings, better families, and better communities, and better societies. That sort of viewpoint would have been regarded as axiomatic in the mid-1930s, and it would have been shared by Left-wing liberals, some socialists, many sort of active and laissez-faire libertarians and old liberals, many new liberals, and many conservatives of all sorts.

The only people who really opposed it were people who were very much linked to certain forms of Biblical Christianity, because of course these ideas are inevitably linked to notions of biological health and reproduction what would later be cast by feminism late in the century, second wave feminism, as reproductive rights but then was looked at as reproduction for health and for eugenic health at that. This meant that contraception and abortion, abortion as a form of contraception, particularly in relation to life which was considered in some respects unworthy or inferior in one category or another, would definitely come into play, and Christians’ moral concerns about that fact of eugenics was very pronounced. However, probably a large number of evangelicals shared semi-eugenic ideas, because racial and national ideas were such much more conservative during this epoch and were so much more hegemonic that it meant that the amount of opposition that eugenics got was relatively small in comparison to the almost universal odium in which its held at the present time.

RS: Let me jump in on that, actually. One of the groups that loathes eugenics at the moment is the evangelical Christians, but it’s worth mentioning that there were eugenic laws in the state of North Carolina, for instance, up until the 1970s and the state sterilized a tremendous amount of people, most of them Blacks who were considered unfit for bearing children. So, there was a kind of old time religious repulsion from eugenics as modernist, and that kind of makes sense. But just to back up your point, it was something that was accepted by a large majority of Protestants in the South.

JB: Yes, the sterilization of the unfit was carried out right across the Western world until a particular generation of natural scientists died out in terms of the social application of biological ideas in the 1970s. Really what you have is a generation that accepts new ideas in the ’30s and ’40s when they are young and carries them out in orphanages and halfway houses and children’s homes and clinics for the elderly and infirm and mental hospitals and waystations for the mentally subnormal and so on and so forth and they carry these functions out right across the ’50s, ’60s, and into the ’70s. That generation then dies out, and the scientists who follow them don’t have the same ideas, because they’ve been exposed to a different and a contrary mindset from 1945/46 onwards.

So, you have a reversal of what went on and at times an unstated reversal whereby the policies just change. The sterilization of people with grossly deformed and inadequate IQs, for example, to prevent them from breeding people who might be described as “idiots” in future, sort of percussive generations. That came to an end in most Western countries around the same time in the mid-1970s, and I think it came to an end because generationally the scientists who’d imbibed eugenic ideas had essentially passed through the system and were retiring and being replaced by a cohort who didn’t share the same notions.

So, you have a reversal of what went on and at times an unstated reversal whereby the policies just change. The sterilization of people with grossly deformed and inadequate IQs, for example, to prevent them from breeding people who might be described as “idiots” in future, sort of percussive generations. That came to an end in most Western countries around the same time in the mid-1970s, and I think it came to an end because generationally the scientists who’d imbibed eugenic ideas had essentially passed through the system and were retiring and being replaced by a cohort who didn’t share the same notions.

I also think it’s important to realize that essentially what’s happened is that two concepts have been conflated into one another in order to summarily dispatch both. This is the idea of eugenics as against dysgenics. Dysgenics, which is, if you like, the negative side of eugenics whereby you act though as to prevent harm but you also act as to, in some senses, prevent life through abortion or through selective contraceptive use or through sterilization. The proactive and yet sort of snip-oriented and negative side of eugenics is its really controversial feature. The wholesome side, the building people up, the tonics for the brave sort of side, is one which only the most niggardly and nihilistic and sordid Left-winger would be opposed to, because they find nauseous the idea of happy, athletic, intellectually precocious families beaming for the camera in an Osmonds-like way, you know. It fills them with nausea and disgust, but a number of people who are filled with nausea and disgust for such sort of pungent healthy normality are relatively few and far between, and many of them are neurotic and sort of outsider-in in their orientation.

That sort of eugenics has been deconstructed so that the term eugenics is no longer used, and it’s just a symbol of healthiness. Although, there are radical Christians of a certain specialization who dislike even that. I remember a Christian woman of my acquaintance a long time ago, a theorist in Christianity, Catholics variants of same, expectorated to me at great length about how she was appalled by pictures of athletes in hospital wards for the sick. She said it’s monstrously eugenic having these pictures of these healthy goddess/god type individuals reminding everyone that’s palsied and lame and sick and broken down what they’re not. And it’s essentially conceptually a form of beating them over the head with a truncheon as they’re trying to get a little bit better in their own terms. And these were just pictures of health. So, it shows you how far the sort of negative reaction to even the idea of healthiness as a perceived good has worked in this society. Illness is dealt with as something to be alleviated, but the corollary that you actually obtain health when you’re not ill is something that has been rather left out of the equation. Doctors who too radically value health fall under a certain cloud and under a certain moral suspicion these days that their viewpoint tends in a semi-eugenic direction.

So, certainly there’s been an incredible reversal, but when most people say “eugenics” the thing that they’re really talking about is the negative side of eugenics. The sort of parsimonious “getting rid of the inferior” dimension to it is what people really get riled against. The more positive agenda would probably get a more sullen acquiescence on behalf of most people who are not sold on the idea that healthiness is not necessarily just next to godliness, but two steps away from Fascism.

RS: Right. And actually it’s worth pointing out that many of the elite are pursuing eugenics. They call it genetic therapy or genetic counseling. I don’t want to dwell on these things, but they are in some ways pursuing negative eugenics in the sense that they are certainly much more willing to abort a child with Down syndrome or so on, and that, of course, can be discovered in the womb. In some ways, one could also suggest that eugenics is still living on. It’s just that you simply can’t use that name, because when you use that a swastika flag begins waving in someone’s mind. It just seems like that is what it is, but the actual practice seems to go on.

I want to return to your mentioning of the academic side of this, but before that, and I think I mentioned this at the beginning of the program, but Nazi Germany did have certain eugenics programs. They were not as unusual as many people would have you believe and they weren’t actually as pronounced as some people would have you believe. In some ways, they were rather hum-drum eugenics programs when compared to what was going on internationally and Hitler’s attacks on the Jewish people and what’s come to be known as the Holocaust was obviously not a eugenic program. Hitler obviously had very strong negative feelings against the Jews and he thought that they were a very dangerous enemy, but he did not think that they were stupid morons or something. Again, when you conflate eugenics and the Holocaust or all of the use of concentration camps and so forth in the Second World War you’re really mixing apples and oranges. They’re just not the same thing. But again, that’s the perception and that is the central reason why eugenics is a kind of non-starter in our contemporary world or it kind of has a sub rosa existence or something like that.

Let me ask you a real quick question, because you were talking about the academic side of this issue and the fact that so many of these researchers who were quite predisposed to Galton, Darwinism, eugenics that switched. Is that part of the so-called Boasian revolution in anthropology? What I mean by that is, of course, Franz Boas, who was a sworn enemy Madison Grant. This is actually one of the things that some of us have forgotten. When Boas was talking about things like there’s no correlation or connection between head size and brain size in intelligence and would even say things that were obviously false and literally fabricated his data claiming that an immigrant’s head would change shape when it came to America. The melting pot would change physics. It’s totally a nonsensical notion. But all those papers he wrote were all directed against Grant and eugenics. That was the target, and sometimes that’s forgotten because Boas’ revolution in anthropology and genetics has been so profound and broad that you forget that he was actually reacting against another force and that was Grant and eugenics, who again were hegemonic.

But, Jonathan, was that what you were getting to when you were talking before about the academic shift among researchers? When you had baby boomers and our generation you were essentially having people who were influenced by Boasian anthropology. They did not think in terms of Galton and let’s call it classical Darwinism. Really those people lost the battle, and this is the reason why eugenics kind of vanished after the Second World War.

JB: Yes, I do think it happened in a certain context though. I think that people who supported eugenics found that unless they found a different vocabulary for it their support couldn’t be sustained in polite society. Therefore, they either found arcane and differentiated terminology or they gave up on it completely, and when you have an idea whose time has come a vanguard will push for a contrary system, and if there’s nothing to push back against them they will take the high ground, and they will take over the theoretical discourse of a society, and you need a very small number of people to be singing from the same hymn sheet, in order to effect that. So, you just need the anthropology societies and the anthropological journals and the anthropology academic departments of the United States to tack one way or to lopsidedly tack one way decisively for there to be a complete re-routing and for one set of theories to be replaced by another one.

But it only happened because the soil was so fertile, because the other discourse had drained away to nothingness, and even those who were in favor of it they found themselves unable to articulate it given the moral climate post-1945.

So, Boas and his friends seized the hour, basically, and introduced forms of social discourse, because that’s what it was, that explained everything in terms of the social ramifications of man, and this very much, of course, fed indirectly into the New Left of the 1960s and ’70s, which is quite a break from the old Left in many ways which would accept quite a lot of prior and inheritable characteristics, even biological ones. Marx and so on never thought that man could be changed biologically in his primary nature. The only change that could be brought about was socio-economic, which could be decisive, but was rudimentary in relation to man’s fundamental being. Lenin, as well, never thought that man was capable of change at the biological level. Some people would always be born stupid; others would be born brilliant; some could approximate to one or the other by dint of some application or its absence. People would be born sick or rattled with disease. People would be born healthy. People would be born with mental diseases and disabilities. And with the exception of socialized medical concern, there’s not too much that could be done about that.

Whereas the New Left believed that everyone is a tabula rasa and that everyone can make it up as they go along and that there are certain things that, of course, impinge, such as extreme illness and that sort of thing, from the biological realm, that’s restricted very much just to the narrow issue of personal health. Other than that, every issue is explicable in terms of social engineering and purely social engineering but not sociobiological engineering. That was rendered out of account. So, progressivism snips off that element of it that was biological in the past, and that’s why eugenics was gotten rid of.

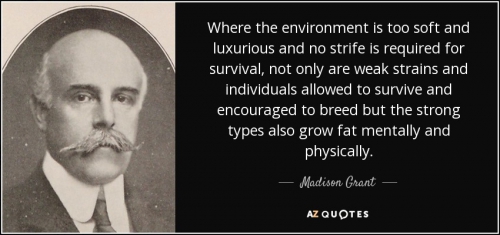

RS: Yes. I want to return to this theme that I was talking about before in terms of Grant and this former hegemonic discourse. I think it’s worth pointing out a little bit about Madison Grant the man, because I think if you really look at his story you really see in a nutshell, as it were, the story of the dispossession of the WASP elite over the course of the 20th century.

Grant was actually a lawyer by training, but he never really practiced. He was very similar to Lothrop Stoddard to that degree, who also had a law degree and also had a PhD, but he was immediately fascinated by naturalism. He was actually involved with people like Theodore Roosevelt and the big game hunter, Boone and Crockett club. He was really pioneering the whole concept of wildlife management and conservation. He was co-founder of the Bronx Zoo in 1899 in his native New York. They would actually bring bison into New York City and things like this.

He was involved in the American Bison Society. There were some statistics that before the society got going and the bison were being conserved — I can’t remember the exact statistic –but it was something like less than 20 bison were remaining. Essentially, the bison is obviously a majestic creature, but when it entered the world of rifles and horse-riding men with guns it was a big slab of meat as a target, and it was being slaughtered. We very well might not have the bison, the American buffalo without someone like Madison Grant.

He was one of the co-founders of Glacier National Park, which I am quite lucky to live about a 45-minute drive away from. It might be second only to Yellowstone National Park. Maybe some might even rank it higher. But it’s a truly gorgeous part of the world that includes all sorts of things from mountain peaks to rivers and lakes. It’s truly a miraculous place.

He was part of the Save the Redwoods League. Redwoods, of course, these massive trees, mostly in California. Again, we shouldn’t forget what still exists today for us to appreciate and what probably wouldn’t exist without the work of Madison Grant and his colleagues.

He was part of the Save the Redwoods League. Redwoods, of course, these massive trees, mostly in California. Again, we shouldn’t forget what still exists today for us to appreciate and what probably wouldn’t exist without the work of Madison Grant and his colleagues.

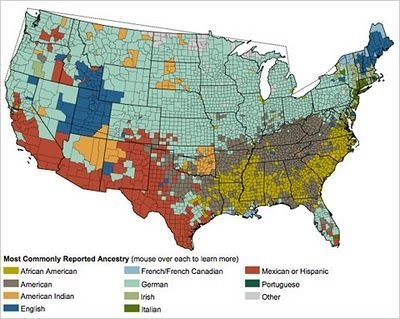

This is someone involved directly with the 1924 Immigration Restriction Act. He was part of the American Defense Society and the American Restriction League, so he was certainly not a politician or a political operative but he was the intellectual force behind these major initiatives which more or less cut off immigration to the United States. I think it did even more than that, because it made sure that America was going to return to what Grant thought of as the Nordic America, the America even before some of the massive Eastern European and Southern European immigration in the second half of the 19th century.

So, this is a man who was part of the elite, he was actually a kind of Brahmin though he was from New York City not Boston, but when you look at these people now you realize that there was this entire elite WASP class that was part of an even deeper tradition that might have included the Adamses and all of these people. Just a totally different version of the American Right than what we have today. In many ways, if you think about it, the kind of Buckleyite-influenced Right is a replacement or a perversion of what we had.

If you think about the history of the life of Madison Grant you really see this other world, a kind of alternative reality for what American conservatism could be.

Do you have any thoughts on that, Jonathan? Maybe America before the Second World War had a chance to have a different path in the world. If people like Madison Grant had been the intellectual leaders and they had been able to influence political leaders. And they were influencing political leaders. Calvin Coolidge was writing articles on how America shouldn’t become a waste dump for the degenerate. He was using extremely strong language that would probably shock some White Nationalists or something. I guess my question is, do you think that there was this other path that America could have taken if people like Madison Grant had prevailed instead of the types of people we have today?

JB: Yes, very much so. I think that the different parts of America could have followed probably proportionate to the issue of isolationism. If America could have remained isolated from not the rest of the world because that’s an impossibility, but isolated from policy involvement with the rest of the world and military intervention in the way it occurred in the First World War, after which there was an isolationist phase, of course, when President Wilson’s dictates were overthrown and there was a return to an isolationist posture. Then the build up to the Second World War, which changed everything and which led to the ascent of globalism as Stephen E. Ambrose calls it in his famous book about the emergence of an American empire as it were, and then the Korean War and then the wars with the Communist blocs and then the war in the modern world that we have today.

I think the influence of such figures would have had is entirely proportionate to the degree to which America remained a republic and not an empire, to use Buchanan’s phrase, and the more imperial America became, the more it became enamored of other models and the less it became enamored of a nativist American model. It’s almost inevitable that nativism would go together with the desire to keep America isolate and keep America out of other conflicts and to keep America from drifting towards global policeman-type roles that it’s been keen to adopt since the mid-1940s, since the attack on Pearl Harbor essentially.

So, I think the general point about men like Grant is that they were from an era where America should have decided its own destiny on its own terms, where the notion of American uniqueness and sort of preferentialism and providentialism, which irritates the hell out of the rest of the world of course, this notion of exceptionalism has been turned around to indicate an imperial or post-imperial vision. But in Grant’s day it was a plea for American uniqueness in American terms, which meant America was to be a society that did not involve itself with the other world particularly but was a New World sufficient unto itself. I think that once America opened up to the forces that wanted it to go global and play a global role, the influence of this old patterned, cross-grained WASP elite was bound to falter and die in the way that it has.

RS: Yes. Well, speaking of the ascent to globalism, I think it’s worth talking about the issue of Haiti, which was quite an important topic for Lothrop Stoddard, who was one of Grant’s protégés and certainly modeled his theories on Grant’s and so on and so forth. He actually wrote his doctoral dissertation on the revolution in San Domingo and that is the race war, for lack of a better term, that occurred on that island after the French Revolution, which was certainly inspired by the French Revolution.

I think it’s worth pointing out a couple of things, to go back to American globalism. In 1915, U.S. Marines were actually sent to Haiti by Woodrow Wilson, and he said that he was going to bring democracy, and they actually remained there for some 20-25 years. They built all sorts of things. That didn’t really work, and then actually in the latter half of Dwight Eisenhower’s administration Marines were sent back to Haiti to keep it from going Communist, and that didn’t do too much. Then in 1994, Bill Clinton actually sought to restore democracy this time around 75 to 100 years later after it was brought to the island.

So, it seems like Haiti has almost been a platform for all of these ideas to play out; that is American globalism, the continual failure of American globalism, and also something which Stoddard talked about which was those revolutionary ideas that would inflame the minds of men.

Maybe, Jonathan, you could just talk a little bit about Stoddard’s rather fascinating book on Haiti and a lot of the ideas he brings up and also just the contemporary relevance of Haiti, how it’s still in the news, we’re still fascinated by ideas of democratizing it or “developing it,” and how this fetish almost won’t ever go away.

JB: Yes, it’s thrown into stark relief by the recent Haitian earthquake and the enormous expenditure of dollars and time and muscle and energy in trying to rebuild Haiti after the earthquake. I remember Alex Kurtagić, I think, wrote a piece on Alternative Right or certainly a similar website that Haiti should not be rebuilt, which of course is an argument for dysgenics in many respects.

The French Revolution in San Domingo by Stoddard dealt with the immediate aftermath of the French Revolution’s impact on Haiti and the tripartite war that developed between the British crown and the Spanish and French authorities there and the emergence of a racially-conscious Black army under Toussaint Louverture and its aftermath in Haiti when Louverture was outmaneuvered by Napoleon, who as history records of course was a racialist which rather shocks people today. When Toussaint was invited to France he was promptly arrested and put in a tower and Napoleon turned to his marshals and said, “You see how I deal with them?”

The French Revolution in San Domingo by Stoddard dealt with the immediate aftermath of the French Revolution’s impact on Haiti and the tripartite war that developed between the British crown and the Spanish and French authorities there and the emergence of a racially-conscious Black army under Toussaint Louverture and its aftermath in Haiti when Louverture was outmaneuvered by Napoleon, who as history records of course was a racialist which rather shocks people today. When Toussaint was invited to France he was promptly arrested and put in a tower and Napoleon turned to his marshals and said, “You see how I deal with them?”

Napoleon’s views on many of these matters are now quite notorious and have led to a de-escalation of the Napoleonic cult that was part and parcel of French intellectual life for the better part of the last 200 years.

So, this racial warfare, which is not too extreme to call it, which subsumed Haiti led to many bloody massacres and internecine strife to the massacre of the residual White, largely French, population and the emergence of a Black republican dictatorship in Haiti for most of the 19th century.

Haiti is essentially an African society in the Western world and closely resembles a society America set up in extreme West Africa called Liberia. The Liberian flag, of course, is the American flag with just one star. Liberia, which America has also intervened in for the best part of a century and a half in order to try to make things right, was to be the resettlement zone for the Black slaves. Lincoln’s policy in relation to Black emancipation had two strands, one of which of course was never realized and that was the second one whereby after the Civil War he wished at least in theory to deport the African population of the United States back to Liberia, which is why this colony was established on the extreme West African coast, but that of course was never carried forward.

But in relation to Haiti, Stoddard sees it is a clear example of White folly in relation to dealing with essentially another race that has different standards of behavior, different characteristics of identity, and will run a society in a completely different manner to that which Europeans would or even semi-Europeans would. The elites in Haiti since the massacring of the Whites in the early 19th century have always been mulatto, of course, have always been of mixed race, including the notorious Haitian dictatorship of the mid-20th century, Papa Doc Duvalier’s regime and the militia called Tonton Macoute through whom he exercised supreme authority. The Americans supported him despite all of the penchants for bloodthirstiness, putting cabinet members to death during cabinet meetings, personal support for voodooism, dispensing money in the streets surrounded by men with weapons: traditional African ways of behaving. The United States of America supported all of this for fear of getting something worse in Haiti. Indeed, America is always intervening to either prevent authoritarianism in Haiti, but also reluctant to endorse certain people who are thrown up by democracy or pseudo-democratic reform. The controversy around President Aristide when Clinton was in power is a testament to this.

The IQ level in Haiti is pathetically low. Their standard of living is extraordinarily low. An enormous proportion of the population still live in shanty towns, still live in wooden huts, still live in cardboard boxes. A significant portion of the people eke out a purely subsistence form of life. One of the reasons the earthquake had such devastating effects was because all of the houses were jerry-built and didn’t have the internal architectural armor that’s necessary to prevent them from falling about people’s ears. Similar earthquakes occur in Japan all the time and hardly anyone is injured at all, and this is because the quality of the building is so much better.

Haiti is essentially a basket-case society. Stoddard’s first of the type in recognition of this. Usually, it’s dealt with anecdotally. There’s a book by St. John at the end of the 19th century called Haiti: The Black Republic, but his analysis of Haiti is anecdotal, really, and sort of spectatorish, whereas Stoddard’s is scientific and eugenic and sociobiological and anthropological and biophysical and racially historical. So, it’s an attempt to systematize what might otherwise appear to be whimsy and a collection of anecdotes about an Africanized society in the Caribbean and the perils and misadventures of it. Stoddard’s view is a systematization of what otherwise could be ethnic and political clichés. But it’s a pretty devastating analysis of Haiti which can’t really be refuted given its current parlous state as a semi-civilized polity.

RS: Yes, one thing that I found quite interesting about his book, which I actually read recently because Alex put out a new edition, was the combination between let’s say Leftist ideology, on one hand, and then genetics and biology on the other. One thing you got from the book is that this pot was simmering for a long time. There was always going to be this racial clash. It was never going to ultimately work. It was going to end in tears and blood. But what really set off the revolution, the catalyst, was this new way of talking that was brought to the island immediately after the French Revolution. That you could soon start talking about the “rights of man” and so on and so forth and that this was like pouring gasoline on the fire, and it almost immediately set off a revolution and a race war on the island.

RS: Yes, one thing that I found quite interesting about his book, which I actually read recently because Alex put out a new edition, was the combination between let’s say Leftist ideology, on one hand, and then genetics and biology on the other. One thing you got from the book is that this pot was simmering for a long time. There was always going to be this racial clash. It was never going to ultimately work. It was going to end in tears and blood. But what really set off the revolution, the catalyst, was this new way of talking that was brought to the island immediately after the French Revolution. That you could soon start talking about the “rights of man” and so on and so forth and that this was like pouring gasoline on the fire, and it almost immediately set off a revolution and a race war on the island.

JB: Yes, and yet the irony is that most of those French revolutionary ideas were never to be applied in that way, because most of the extreme revolutionaries in France, such as the Club des Cordeliers or Club des Jacobins, the two major revolutionary clubs, only ever thought those ideas would be applicable to Europeans, to Frenchmen in particular and White men in general. They never thought that those ideas would be applicable to other groups and, although there were always those who wished to go further, there was no tendency in France apart from on the fringes of the fringes — and this was among a revolutionary class, don’t forget — to emancipate the slaves. Nor was there any move to, particularly. And Napoleon certainly put the kibosh on that, because he had no intention of doing so, just as there was no intention to extend these ideas in relation to women. This was regarded as absurd even by the Jacobins themselves, and the most radical people on the Jacobin side, people like Robespierre and Saint-Just, deprecated the idea that these were always for export and always to be reinterpreted in different contexts, although there were people who saw a correlation and believed that the universalism of the Declaration of the Rights of Man.

RS: Well, there was the group, the Amis des noirs, the Friends of the Blacks, that I remember were kind of taking Leftism to its ultimate conclusion. In some ways, what we’re talking about is the history of the Left in general, which has moved from advocating for working people or the proletariat towards advocating for the wretched of the Earth and the Third World. In some ways, that is the movement of the Left in a nutshell over the past 100 years or so.

In closing, Jonathan, let me bring up another movement which is associated with the Left, but it’s also one that’s associated with Madison Grant, and it’s one that I truly hope that our side, our little fringe contingent, might reclaim at some point and I think we should be working to reclaim it right now and that is environmentalism, so-called. I actually don’t even like the word “environmentalism.” I like saying the word “naturalist” or that we want to “conserve nature” is a better term. “Nature” evokes all sorts of things, has all sorts of connotations which I think are much more positive than “environment,” which seems kind of sterile.

Obviously, Madison Grant was a scientist, but he also wanted to preserve, say, the bison, because they were a majestic animal. He thought they were beautiful. He obviously wanted to preserve Glacier National Park, or the area therein, because it was some of the most spectacular grounds on the Earth. I think one way that we could bring to environmentalism and which I think is the most healthy and positive aspect of environmentalism and which actually attracts people as opposed to the other environmentalist movements of global government and things like this that are not very attractive, but what attracts people is the idea of nature, the beauty of nature and experiencing nature.

So, maybe we could just close on that thought, Jonathan. What do you think about our unique ability to reclaim conservationism or naturalism and how, much like Grant, that should be a major cause for us, which is to keep the world green and beautiful and to fight things like the terrible overpopulation that you see in some kind of horrifying city like Mexico City or São Paulo? We want quality over quantity and we want to live on a beautiful Earth. So, what are some of your thoughts on that idea?

JB: Yes, I think that’s mirrored in green ideas itself, because green ideas are not really part of the Left-Right spectrum but they cut across it in various respects. Green ideas are also circular, because there’s a sort of light green outer circle and a dark or deep green, as it’s called, inner circle. And the deep green ideas are very interesting, even misanthropic to a point with doctrines like Gaia and so on that see mankind as a sort of excrescence upon the Earth and the Earth only has value. This is part of the tendency all ideas have to maximize their own extremism and adopt at the margin a fundamentalism of their own coinage.

Nevertheless, certain more moderate deep green ideas are deeply susceptible to a Right-wing coinage. The conservation of all forms of natural beauty, extreme forms of localism, forms of animal husbandry that are linked to preservation of animal species and biodiversity but are not linked to doctrines of rights and animal rights or animal liberation but draw on a similar metaphysic but end in a different place because it begins in one. You see this very much, say, with the split in Britain between a sort of anarchist group like the Animal Liberation Front and a conservationist group like the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. The two sort of overlap in terms of some of their coteries, but ideologically they’re very much at variance because the one is conservative, small c, and ameliorative and piece-by-piece and localist, whereas the other wishes to extend the universal doctrine of human rights to animal species and has developed a concept of animal racism, of course, namely speciesism. All of which is an outgrowth of the politics of human rights. But if one eschews the politics of human rights in a grandstanding and universalist way and sees human identity and glory in very much an individual or localized manner then deep green and ecological ideas have a lot to say to all forms of conservativism that wish to preserve and restore as against that which is transitory and that which is to our end and which is purely and only concerned with human life to the detriment of the ecology without which mankind couldn’t subsist.

Nevertheless, certain more moderate deep green ideas are deeply susceptible to a Right-wing coinage. The conservation of all forms of natural beauty, extreme forms of localism, forms of animal husbandry that are linked to preservation of animal species and biodiversity but are not linked to doctrines of rights and animal rights or animal liberation but draw on a similar metaphysic but end in a different place because it begins in one. You see this very much, say, with the split in Britain between a sort of anarchist group like the Animal Liberation Front and a conservationist group like the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. The two sort of overlap in terms of some of their coteries, but ideologically they’re very much at variance because the one is conservative, small c, and ameliorative and piece-by-piece and localist, whereas the other wishes to extend the universal doctrine of human rights to animal species and has developed a concept of animal racism, of course, namely speciesism. All of which is an outgrowth of the politics of human rights. But if one eschews the politics of human rights in a grandstanding and universalist way and sees human identity and glory in very much an individual or localized manner then deep green and ecological ideas have a lot to say to all forms of conservativism that wish to preserve and restore as against that which is transitory and that which is to our end and which is purely and only concerned with human life to the detriment of the ecology without which mankind couldn’t subsist.

RS: Absolutely. I mentioned this before. There’s a very useful biography of Madison Grant and it’s by a man named Spiro. Although he seems to be a Left-liberal of some kind, he clearly wants to get it right and that’s certainly admirable. He offers a very useful and rich biography of Grant, which has really influenced my interest in Grant, and one of his major themes is that if you tell someone that Grant is an early environmentalist that’ll usually bring a smile to their face, but if you tell someone he’s also an early eugenicist that will usually inspire shock and horror. But as Spiro points out, there was no contradiction in Grant’s mind between saving the redwoods and saving the White race. Those were part of the same movement, so as I mentioned before, I think we are uniquely suited to generate a sort of renaissance of green or naturalist or environmentalist politics.

Jonathan, let’s just put a bookmark in the conversation right there, and I would love to return to these ideas in the near future and I look forward to speaking to you soon.

JB: Yes, thanks very much! All the best. Bye for now!

Related

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Certainly, something like the National Socialist regime in Germany did have eugenics programs. They were not actually as pronounced as some might believe. They actually modeled a lot of those programs on the eugenics programs found in Sweden and in the state of California. California was probably the ultimate model. You had eugenics being endorsed by university presidents. That is, it was very much endorsed by the elite. They thought this was a good thing and it was also a part of the progressive elite. Eugenics was not a reactionary opinion. It was something that was opposed by the old time religion folks or whom you might call reactionaries. It was something that might even be on the Left in certain contexts. Certainly, with somebody like Lothrop Stoddard, who we’re going to speak about a little bit later, it was a position held by someone who openly thought of himself as a progressive and a modernist. And it also had some popular appeal. Actually, in a talk I gave not too long ago at the H. L. Mencken Club, I showed some pictures that were actually taken by a very good book, a biography of Lothrop Stoddard which was written by a Left-liberal who doesn’t like Stoddard very much but recognizes his importance, but these pictures were of eugenic buildings at the state fair. I believe a famous one was from the Kansas State Fair. They would have a competition for the fittest family, and what they wanted to see was a good genotype. That was a healthy family with all boys and girls looking strong and smart and good-looking parents and things like this. So, eugenics really had a positive value in peoples’ lives. It was something that meant that they were healthy and good and normal and people of quality. Obviously, this has gone through a total reversal.

Certainly, something like the National Socialist regime in Germany did have eugenics programs. They were not actually as pronounced as some might believe. They actually modeled a lot of those programs on the eugenics programs found in Sweden and in the state of California. California was probably the ultimate model. You had eugenics being endorsed by university presidents. That is, it was very much endorsed by the elite. They thought this was a good thing and it was also a part of the progressive elite. Eugenics was not a reactionary opinion. It was something that was opposed by the old time religion folks or whom you might call reactionaries. It was something that might even be on the Left in certain contexts. Certainly, with somebody like Lothrop Stoddard, who we’re going to speak about a little bit later, it was a position held by someone who openly thought of himself as a progressive and a modernist. And it also had some popular appeal. Actually, in a talk I gave not too long ago at the H. L. Mencken Club, I showed some pictures that were actually taken by a very good book, a biography of Lothrop Stoddard which was written by a Left-liberal who doesn’t like Stoddard very much but recognizes his importance, but these pictures were of eugenic buildings at the state fair. I believe a famous one was from the Kansas State Fair. They would have a competition for the fittest family, and what they wanted to see was a good genotype. That was a healthy family with all boys and girls looking strong and smart and good-looking parents and things like this. So, eugenics really had a positive value in peoples’ lives. It was something that meant that they were healthy and good and normal and people of quality. Obviously, this has gone through a total reversal. So, you have a reversal of what went on and at times an unstated reversal whereby the policies just change. The sterilization of people with grossly deformed and inadequate IQs, for example, to prevent them from breeding people who might be described as “idiots” in future, sort of percussive generations. That came to an end in most Western countries around the same time in the mid-1970s, and I think it came to an end because generationally the scientists who’d imbibed eugenic ideas had essentially passed through the system and were retiring and being replaced by a cohort who didn’t share the same notions.

So, you have a reversal of what went on and at times an unstated reversal whereby the policies just change. The sterilization of people with grossly deformed and inadequate IQs, for example, to prevent them from breeding people who might be described as “idiots” in future, sort of percussive generations. That came to an end in most Western countries around the same time in the mid-1970s, and I think it came to an end because generationally the scientists who’d imbibed eugenic ideas had essentially passed through the system and were retiring and being replaced by a cohort who didn’t share the same notions. He was part of the Save the Redwoods League. Redwoods, of course, these massive trees, mostly in California. Again, we shouldn’t forget what still exists today for us to appreciate and what probably wouldn’t exist without the work of Madison Grant and his colleagues.

He was part of the Save the Redwoods League. Redwoods, of course, these massive trees, mostly in California. Again, we shouldn’t forget what still exists today for us to appreciate and what probably wouldn’t exist without the work of Madison Grant and his colleagues. The French Revolution in San Domingo by Stoddard dealt with the immediate aftermath of the French Revolution’s impact on Haiti and the tripartite war that developed between the British crown and the Spanish and French authorities there and the emergence of a racially-conscious Black army under Toussaint Louverture and its aftermath in Haiti when Louverture was outmaneuvered by Napoleon, who as history records of course was a racialist which rather shocks people today. When Toussaint was invited to France he was promptly arrested and put in a tower and Napoleon turned to his marshals and said, “You see how I deal with them?”

The French Revolution in San Domingo by Stoddard dealt with the immediate aftermath of the French Revolution’s impact on Haiti and the tripartite war that developed between the British crown and the Spanish and French authorities there and the emergence of a racially-conscious Black army under Toussaint Louverture and its aftermath in Haiti when Louverture was outmaneuvered by Napoleon, who as history records of course was a racialist which rather shocks people today. When Toussaint was invited to France he was promptly arrested and put in a tower and Napoleon turned to his marshals and said, “You see how I deal with them?” RS: Yes, one thing that I found quite interesting about his book, which I actually read recently because Alex put out a new edition, was the combination between let’s say Leftist ideology, on one hand, and then genetics and biology on the other. One thing you got from the book is that this pot was simmering for a long time. There was always going to be this racial clash. It was never going to ultimately work. It was going to end in tears and blood. But what really set off the revolution, the catalyst, was this new way of talking that was brought to the island immediately after the French Revolution. That you could soon start talking about the “rights of man” and so on and so forth and that this was like pouring gasoline on the fire, and it almost immediately set off a revolution and a race war on the island.

RS: Yes, one thing that I found quite interesting about his book, which I actually read recently because Alex put out a new edition, was the combination between let’s say Leftist ideology, on one hand, and then genetics and biology on the other. One thing you got from the book is that this pot was simmering for a long time. There was always going to be this racial clash. It was never going to ultimately work. It was going to end in tears and blood. But what really set off the revolution, the catalyst, was this new way of talking that was brought to the island immediately after the French Revolution. That you could soon start talking about the “rights of man” and so on and so forth and that this was like pouring gasoline on the fire, and it almost immediately set off a revolution and a race war on the island. Nevertheless, certain more moderate deep green ideas are deeply susceptible to a Right-wing coinage. The conservation of all forms of natural beauty, extreme forms of localism, forms of animal husbandry that are linked to preservation of animal species and biodiversity but are not linked to doctrines of rights and animal rights or animal liberation but draw on a similar metaphysic but end in a different place because it begins in one. You see this very much, say, with the split in Britain between a sort of anarchist group like the Animal Liberation Front and a conservationist group like the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. The two sort of overlap in terms of some of their coteries, but ideologically they’re very much at variance because the one is conservative, small c, and ameliorative and piece-by-piece and localist, whereas the other wishes to extend the universal doctrine of human rights to animal species and has developed a concept of animal racism, of course, namely speciesism. All of which is an outgrowth of the politics of human rights. But if one eschews the politics of human rights in a grandstanding and universalist way and sees human identity and glory in very much an individual or localized manner then deep green and ecological ideas have a lot to say to all forms of conservativism that wish to preserve and restore as against that which is transitory and that which is to our end and which is purely and only concerned with human life to the detriment of the ecology without which mankind couldn’t subsist.

Nevertheless, certain more moderate deep green ideas are deeply susceptible to a Right-wing coinage. The conservation of all forms of natural beauty, extreme forms of localism, forms of animal husbandry that are linked to preservation of animal species and biodiversity but are not linked to doctrines of rights and animal rights or animal liberation but draw on a similar metaphysic but end in a different place because it begins in one. You see this very much, say, with the split in Britain between a sort of anarchist group like the Animal Liberation Front and a conservationist group like the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. The two sort of overlap in terms of some of their coteries, but ideologically they’re very much at variance because the one is conservative, small c, and ameliorative and piece-by-piece and localist, whereas the other wishes to extend the universal doctrine of human rights to animal species and has developed a concept of animal racism, of course, namely speciesism. All of which is an outgrowth of the politics of human rights. But if one eschews the politics of human rights in a grandstanding and universalist way and sees human identity and glory in very much an individual or localized manner then deep green and ecological ideas have a lot to say to all forms of conservativism that wish to preserve and restore as against that which is transitory and that which is to our end and which is purely and only concerned with human life to the detriment of the ecology without which mankind couldn’t subsist.