We live in an age of decolonisation, in which big empires have broken up and more and more independent states are coming on to the map. It might therefore seem surprising that Scotland has just voted against independence. In fact, it might just have done the opposite.

Unlike Wales and Ireland, Scotland was never actually conquered by the English. It was a fully independent state for many centuries, and usually allied with France against England. It had its own king and a variety of English it regarded as a separate language. Scots Gaelic, which is incomprehensible to English or Scots speakers, also flourished.

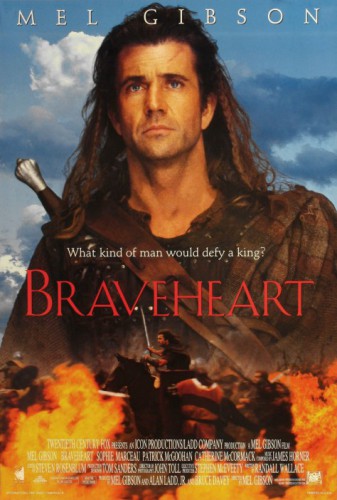

The English king often regarded himself as the feudal overlord of the Scottish king, but Scotland retained its independence even in conflict. Despite the great contributions made by many famous Scots to the United Kingdom, it is Robert the Bruce and William Wallace, who fought for Scottish independence from English domination, who remain its national heroes.

This situation changed in 1603, when King James I of Scotland also became King James I of England as he was next in line to the English throne. Logistics dictated that he and his successors were usually in London. A century later the Scottish Parliament abolished itself and the Act of Union created a common country called Great Britain. This became the United Kingdom in 1801, when the Irish Parliament also voted to abolish itself, Ireland having been effectively ruled by England since Norman times.

The United Kingdom went on to become the world’s greatest superpower. In consequence, many of the usual drivers of separatist sentiment weren’t there. There were no such things as national minorities amongst the British, just different sorts of British people. Everyone was entitled to some piece of the attractive pie, however small, provided they knew their place.

The Scots always played a big part in spreading British power across the globe, through making things and being part of government. Not until the 1970s did the Scottish National Party have a consistent presence in the UK parliament, and even then it held a small minority of Scottish seats, the same parties they have in England claiming all the others, on broader UK-wide platforms, as they do today.

So the referendum on Scotland was not about correcting historic injustices, as these do not engage most electors. It was about whether the Scots need to have an independent country to feel Scottish. It was also about how Scottish their own leaders are, and ultimately this has proved the downfall of the independence advocates.

Yes to Scotland but no to you

The Yes campaign was predictably led by the SNP, the Scottish Nationalist Party, and its longtime de facto leader Alex Salmond. Though a popular figure, Salmond is also controversial, and the one depends upon the other.

Although many political leaders have been expelled from their original party and founded a new one Salmond is one of the few who has been expelled from the one he now leads. When consistent SNP gains came to a shuddering halt in 1979, the party then split between the radical faction to the left of Labour and the romantically nationalist “Tartan Tories”, which succeeded in expelling Salmond and friends for being too leftist. Eventually he won his argument, but at a price.

The SNP is a moderate, mainstream political force but has one thing in common with the extreme and excluded nationalists found in every country. It takes it upon itself to define who is and who is not Scottish, what Scottish should and should not do and what Scottish people should and should not think. It isn’t said in as many words, but if you don’t agree with the SNP you are not a real Scot, in SNP thinking.

There are plenty of Scots around who don’t need the SNP to tell them what to do. They don’t think disagreeing with the SNP makes them any less Scottish, particularly when the person telling them they are has got to where he is by sidelining another faction within the same party. People who may like independence in principle don’t want an SNP independence, and this has affected the result of the referendum.

The devil we don’t want to know

One of the historic grievances which might compel Scots to demand independence is that the country has long been taken for granted by the English. Like Wales, it has been treated as a source of raw materials and labour, and somewhere people can go for their holidays. Local cultures and traditions are seen as something out of history, even though the Scots are much more cultured and better educated than the English, appreciating the importance of literature, for example.

However the Scots mourn the departure of the predominantly working-class culture created by English rule. It is a nation of engineers and skilled workers, whose shipbuilding industry once ruled the world and whose major settlements were largely built around mineral exploitation. That world has largely gone now, but the English, and particularly Mrs. Thatcher, are blamed for this.

The Scotland most electors relate to is the one of their forefathers, the one where everyone worked for the English. It wasn’t ideal, but it still gives them a distinct identity – more than anything the SNP were offering. Scottish politics remains dominated by how to return to the glory days of full employment, and these came under the United Kingdom, like it or not. Being independent for its own sake did not prove attractive enough for people who know they are different anyway, and aren’t any less different as part of the UK.

Scotland traditionally votes Labour, even when there are big Conservative majorities in the UK as a whole. A big reason for this is that the “establishment”, which might be considered Conservative, is England, and Scots are defining themselves in relation to the rest of the UK. If Scotland were independent, it would no longer be necessary for the voters to define themselves in terms of the English, and the SNP itself would also be affected by this. Vested interests were not going to let that happen, and the Yes campaign failed to address the consequences of the sea change in perceptions independence would have brought.

Too good to care

Of course Scotland now has its own parliament again, with significant powers and the right to set different tax levels to the rest of the UK, within certain limits. It has also done rather well out of this arrangement. It is widely acknowledged that public services are better in Scotland than in England, and some English people have moved there for this reason. Complaints about corruption in Holyrood, home of the Scottish parliament, are nothing like the expenses and child abuse scandals which have rocked the UK parliament, even though Scots sitting in Westminster have also been involved in these.

All this implies that the Scots are just as capable as the English of governing themselves, but that very comparison hurt the Yes campaign. It adds to the Scottish identity to be better than the English when they are supposed to be the same, or worse. If Scotland becomes independent it will no longer be relevant whether it does things better than in England, there will be no reason for comparison. Scots will have their own virtues but also their own problems, and only they will be responsible for them.

The Scots are not going to give up their bragging rights. Though presented as a “sense versus sentiment” argument, the No campaign was more appealing precisely to those who have a sentimental attachment to what they see as Scotland and Scottishness. Scots always want to score points over their big bad brother. There wouldn’t be the same point in being Scots if they had to treat the English as foreign friends instead of unhealthy domestic rivals, in their estimation.

Who owns what

If Scotland had voted yes, there would have been considerable debates over who owns what. Everything Scottish actually belongs to the United Kingdom, just as everything in England does. But Scots have always maintained that the British facilities they like, such as the oil deposits situated off the Scottish coast, are rightfully theirs, while those they don’t like, like the nuclear submarine bases and power plants, are English impositions, alien to Scottish culture.

British Prime Minister Cameron, whose name is Scottish and means “twisted nose”, has promised much more devolved power to Scotland and other parts of the UK in return for the No vote. It is highly likely that, if Westminster delivers on its promises, Scots will have far greater control over their resources than they would have done in an independent state. The view of a partner government or local authority, whose powers were granted it by the English, will have to be taken into account. The views of a national government imposed after the relevant agreements were made, which people in the rest of the UK had no say in creating, are not likely to be respected if things like defence establishments are being discussed.

The No vote might ironically deliver more of what the Yes supporters actually wanted, even though the legal framework being offered remains unacceptable to them. It might also deliver more power to communities and national groups throughout the UK, thus giving the Scots more bragging rights, and confirming their identity, more than actual independence, and having to pay for it, would have done. If so, the Yes campaign will claim victory too, in true British fashion, but with considerable justification.

Conclusion

Independence is about identity. The Scots know who they are in relation to the English, so they’ve chosen to remain who they know they are. What they would be without the English to blame was less clear, as the actual idea of independence and separateness is understood and accepted anyway, without the need for any vote on the subject.

The Scots have demonstrated their independence by flying in the face of world opinion. They have stated, for the first time in a generation, that being independent doesn’t have to mean actually running your own country. They haven’t done so by much, but they have, and all Scots will respect this result, thus again confirming that they don’t need to be told what Scots should do.

Less secure nations are continually demanding independence because that is the only way they feel they can be part of the family of nations. The Scots don’t have that feeling. Maybe this is the beginning of new models being worked out which suit more people. The only problem is that nobody outside Scotland will think of asking Scottish Yes campaigners to be part of that process, but that is the sort of price Scotland is prepared to pay.

Seth Ferris, investigative journalist and political scientist, expert on Middle Eastern affairs, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.

First appeared: http://journal-neo.org/2014/09/25/why-the-scots-chose-to-wear-their-chains-with-pride/

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg