mardi, 26 mars 2013

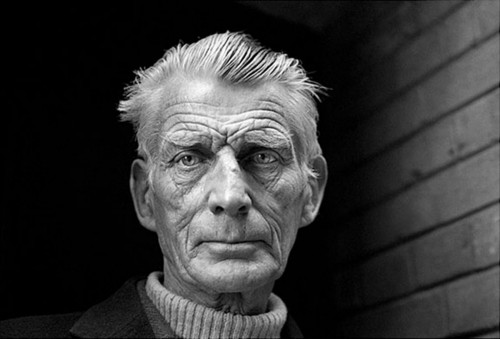

Thoughts on Samuel Beckett

Thoughts on Samuel Beckett

By Jonathan Bowden

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Edited by Alex Kurtagić

Editor’s Note:

The following is excerpted from Jonathan Bowden’s Skin, a book he wrote in the early 1990s. The text has been lightly edited, mainly for punctuation, spelling, and capitalization.

In Samuel Beckett’s work . . . , which has become emblematic of the modern condition, particularly in the arts, there is a struggle with inarticulacy, where inarticulacy stands for silence—the absence at the heart of existence. As a result, Beckett’s work was the outcome of a profound struggle between form and the absence of form. This was the attempt to incorporate the mess of chaos or existence into a work of art—something that orders experience. As a consequence, artistic expression has a strongly authoritarian bias, although postmodernism tends to refute this. Beckett’s work, in other words, was an attempt to shape fundamental sounds from the chaos of identity. It was an attempt to retrieve the semblance of form from the absence of form. His work was an attempt to capture the process, the nature of entropy, the transition between different states. Indeed, it is no surprise to use that one of the journals that published Beckett was called Transition (edited by individuals like Eugene Jolas, in Paris, on either side of the war). Once, when Becket was irritated by Pinter’s insistence on form in his work, he said ‘I was once in a hospital and in the next ward a man was dying from cancer of the throat. I could hear his screams constantly throughout the night. If you are looking for form in my work then that is the form it takes!’ All of which is illustrated by the fact that when Beckett was asked to stage a play at the Gate Theatre in Dublin (the seat of Irish experimentation in the manner of the European avant garde, he intervened in the script to ask a basic question: ‘what does the world resemble?’ And a character, propping up the bar, answered: ‘A large human head, distended in space, covered in pus, exuding scabs, horrible to behold—revolting, disgusting.’ The rest of the cast and the scriptwriting committee agreed, and refused to include Beckett’s anecdote.

Nevertheless, Beckett’s work (like the work of Francis Bacon, which it resembles), is an attempt at a realistic form of nihilism at the end of the 20th century. We can also see that there is a strongly materialistic element in Beckett’s theatre, hence his desire for total control of the actors on the stage. In summation, Beckett wants to reduce the actors to automata or robots. In a way, therefore, he is a cyberneticist as much as a playwright. He once confessed to Roger Blin that all he wanted on stage was a pair of ‘blubbering lips’, something which he attempted to achieve with Billie Whitelaw in a play like Not I, which was performed at the Royal Court during the 1970s. As a result, Beckett’s desire for total control, his artistic psychosis, if you will, has increasingly led towards minimalism in literature and in drama.

Minimalism has often been misunderstood: it is less a desire for purity of form than a need for control. There is something manic and peculiarly modern in minimalism, the attempt to gain complete control over a work and its audience. It can be said, therefore, that minimalism has to do with the absence of form, due to the desire to rid artistic processes of any clutter. In short, the spare, clean outlines of the minimalist are an attempt to gain control of the subject matter of a piece. Thus, minimalism is a strategy, a rear-guard action on behalf of the artist. It is, in essence, an attempt to impose new forms on the breakdown of all possible forms.

Minimalism has often been misunderstood: it is less a desire for purity of form than a need for control. There is something manic and peculiarly modern in minimalism, the attempt to gain complete control over a work and its audience. It can be said, therefore, that minimalism has to do with the absence of form, due to the desire to rid artistic processes of any clutter. In short, the spare, clean outlines of the minimalist are an attempt to gain control of the subject matter of a piece. Thus, minimalism is a strategy, a rear-guard action on behalf of the artist. It is, in essence, an attempt to impose new forms on the breakdown of all possible forms.

Beckett, for his part, was strongly influenced by Schopenhauer, Descartes, and Descartes’ pupil, the Belgian philosopher Geulincx. Descartes developed an extreme form of abstraction, where mind and body come to be separated, at least in the mind. Of course, this is a form of stupidity, since mind and matter are different versions of the same thing—something that does not privilege the emotions over the intellect, as Wyndham Lewis once supposed in The Art of Being Ruled. To suggest an integrative vision of body and psyche is to avoid the trap of seeing the two as separate entities. It is certainly not an attempt to level the intellect or champion the vulva, the uterus, and the spleen against it. Such things only become a cultural afflatus, a torrent of unreason, when they deny reason to instinct and emotion to rationality. The throbbing, insensate nature of ‘black culture’—ludicrously overrated by academics like Dick Hebdidge—is merely the downside of White indifference.

Nevertheless, Beckett always needed Descartes’ philosophy, his Cartesian romanticism, because it covered an essential weakness: a psychic imbalance. Beckett was a neurotic who only felt secure when he could control and compartmentalise his life, his friends, and acquaintances. It a sense he had never grown up; he had not reached beyond the adolescent stage of maturation, and as Jung remarked in a lecture at the Tavistock clinic, which had a remarkable effect on becket, ‘he had never been born entirely’.

Moreover, Beckett was strongly influenced by Schopenhauer’s idea—this thinker’s pessimistic speculation—that in a world dominated by will—what Nietzsche would call ‘the will to power’— the sole purpose of an intellectual man’s life was to safeguard the nature of his own will. In other words, in a world ruled by will, a man had to retreat from the world in order to achieve the nature of his own will. Such ideas involved a retreat from the world into the domain of private speculation—what we might call a ‘scholarly retreat’, while this ideology also involved a conscious apoliticism, a refusal to act politically, and the avoidance of social questions. In fact, it involved the attempt to cut oneself off from one’s own world. Hence, we see the introverted and solipsistic nature of this philosophy—what we might call its artificial attempt to erect barriers between similar things; its attempt to float out of the world in order to realise oneself in the world of one’s own mind.

Beckett was also strongly influenced by Geulincx’s idea that a man could control nothing but his own mind. As a result, he believed that men should retreat into their own minds in order to achieve their own will. He realised that the world showed an abundance of Will that had to be outfaced by retreating into the nature of one’s own will. Geulincx, for his part, believed that a man should want nothing he could not control, and he should be prepared to let the rest go. According to Geulincx, everything outside the mind was beyond the provenance of the mind, and, as such, it was unobtainable. Indeed, it was best left alone, primarily because it could not be contemplated in the fastness of the mind. In these circumstances, everything outside a man’s mind, including his own body, was of no account because he could not control it. For the intellectual or mental gymnast, there was no other option but to retreat from the world into the security of his own mind.

Hence, we see the increasing spareness of Beckett’s writing: the short passages that were farted out towards the end of his life. Beckett’s later writings resemble a farrago, a diminuendo, a restraint on reason. They grow shorter and shorter, and sparer and sparer. Indeed, towards the end they almost cease to exist. They come to resemble a body that is in the last stages of dissolution. Towards the end of his life Beckett’s editions were slight, flippery things, and they were often printed in extra large letters, eighteen or nineteen points, like print in books for octogenarians, with a large white margin around the text in order to illustrate its brevity.

Beckett’s strategy, however, is flawed and uncertain, and it is somewhat cruel and psychotic. In particular, his avoidance of political issues is a grave weakness that ultimately defeats the whole thing.

Source: http://www.wermodandwermod.com/newsitems/news130320131319.html [2]

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2013/03/thoughts-on-samuel-beckett/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: http://www.counter-currents.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/beckett.jpg

[2] http://www.wermodandwermod.com/newsitems/news130320131319.html: http://www.wermodandwermod.com/newsitems/news130320131319.html

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Nouvelle Droite | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | Tags : littérature, littérature française, lettres, lettres françaises, samuel beckett, en attendant godot, nouvelle droite, jonathan bowden |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Commentaires

Thoughts on Samuel Beckett : Euro-Synergies, ¿Puedes explicarnos màs?, me resulta didactico esta informacion. Saludos.

Écrit par : sillas y mesas hosteleria | jeudi, 01 août 2013

Les commentaires sont fermés.