The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914, By Christopher Clark, HarperCollins, New York 2013, 697pp.

The question of the causes of the outbreak of the First World War—known for many years during and afterwards as the Great War—is probably the most hotly contested in the whole history of historical writing.

At the Paris Peace Conference, the victors compelled the vanquished to accede to the Versailles Treaty. Article 231 of that treaty laid sole responsibility for the war’s outbreak on Germany and its allies, thus supposedly settling the issue once and for all.

The happy Entente fantasy was brutally challenged when the triumphant Bolsheviks, with evident Schadenfreude, began publishing the Tsarist archives revealing the secret machinations of the imperialist “capitalist” powers leading to 1914. This action led the other major nations to publish selective parts of their own archives in self-defense, and the game was afoot.

Though there were holdouts, after a few years a general consensus emerged that all of the powers shared responsibility, in varying proportions according to the various historians.

In the 1960s, this consensus was temporarily broken by Fritz Fischer and his school, who reaffirmed the Versailles judgment. But that attempt collapsed when critics pointed out that Fischer and his fellow Germans focused only on German and Austrian policies, largely omitting parallel policies among the Entente powers.

And so the debate continues to this day. A meritorious and most welcome addition is The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914, by the Cambridge University historian Christopher Clark.

Clark explains his title: the men who brought Europe to war were “haunted by dreams, yet blind to the reality of the horror they were about to bring into the world.” The origins of the Great War is, as he states, “the most complex event of modern history,” and his book is an appropriately long one, 697 pages, with notes and index.

The crisis began on June 28, 1914 with the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, and his wife Sophie in Sarajevo, the capital of the Austrian-annexed province of Bosnia. It had its roots, however, in the small neighboring kingdom of Serbia and its strange history. As Serbia gradually won its independence from the Ottoman Turks, two competing “dynasties”—in reality, gangs of murdering thugs—came to power, first the Obrenovic then the Karadjordjevic clan (diacritical marks are omitted throughout). A peculiar mid-nineteenth-century document, drawn up and published by one Iliya Garasanin, preached the eternal martyrdom of the Serbian people at the hands of outsiders as well as the burning need to restore a mythical Serbian empire at the expense both of the Ottomans and of Austria. According to Clark, “until 1918 Garasanin’s memorandum remained the key policy blueprint for Serbia’s rulers,” and an inspiration to the whole nation. “Assassination, martyrdom, victimhood, the thirst for revenge were central themes.”

When Austria annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908 after an occupation of forty years, all of Serbia was outraged. The prime minister, Nicola Pasic, and other leaders spoke of the “inevitable” life-and-death struggle against Austria in the sacred cause of “Serbdom.” Yet the country was economically backwards, the population largely illiterate. What was required was a great-power sponsor. This they found in Russia.

The new Russian ambassador to Belgrade was Nikolai Hartwig, a fanatical pan-Slavist. A huge loan from France (for decades Russia’s close ally) was arranged, to improve and modernize the Serbian army.

Hartwig came in contact with a co-conspirator, Dragutin Dimitrijevic, known as Apis, who was chief of Serbian Military Intelligence. At the same time he headed a secret society, “Union or Death,” or the Black Hand. It infiltrated the army, the border guard, and other groups of officials. The Black Hand’s modus operandi was “systematic terrorism against the political elite of the Habsburg Empire.” Apis was the architect of the July plot. He recruited a group of Bosnian Serb teenagers steeped in the mythology of eternal Serbian martyrdom.

The Archduke was not targeted because he was an enemy of the Serbs. Quite the contrary. As Gavrilo Princip, the actual assassin, testified when the Austrians put him on trial, the reason was that Franz Ferdinand “would have prevented our union by carrying out certain reforms.” These included possibly raising the Slavs of the empire to the third ethnic component, along with the Germans and Magyars or at least ameliorating their political and social position.

The young assassins were outfitted with guns and bombs from the Serbian State Arsenal and passed on into Bosnia through the Black Hand network. The conspiracy proved successful, as the imperial couple died on the way to the hospital. The Serbian nation was jubilant and hailed Princip as another of its many martyrs. Others were of a different opinion. One was Winston Churchill, who wrote of Princip in his history of the Great War, “he died in prison, and a monument erected in recent years by his fellow-countrymen records his infamy, and their own.”

All the evidence points to Pasic knowing of the plot in some detail. But the message passed to the Austrians alluded only to unspecified dangers to the Archduke should he visit Bosnia. The fact is, as Clark states, Pasic and the others well understood that “only a major European conflict involving the great powers ‘would suffice to dislodge the formidable obstacles that stood in the way of Serbian ‘reunification.”’

In a major contribution the author refutes the notion, common among historians, that Austria-Hungary was on its last legs, the next “sick man of Europe,” after the Ottomans. The record shows that in the decades before 1914, it experienced something of aWirtschaftswunder, an economic miracle. In addition, in the Austrian half at least, the demands of the many national minorities were being met: “most inhabitants of the empire associated the Habsburg state with benefits of orderly government.” The nationalists seeking separation were a small minority. Ironically, most of them feared domination by either Germany or Russia, if Austria disappeared.

Following the Bosnian crisis of 1908, “the Russians launched a program of military investment so substantial that it triggered a European arms race.” The continent was turned into an armed camp.

France was as warm a supporter of Serbia as Russia. When the Serbian king visited Paris in 1911, the French president referred to him at a state dinner as the “King of all the Serbs.” King Petar replied that the Serb people “would count on France in their fight for freedom.”

The two Balkan wars of 1912-1913 intensified the Serbian danger to Austria. The terrorist network expanded dramatically, and Serbia nearly doubled in size and saw its population increase by forty per cent. For the first time Austria had to take it seriously as a military threat.

The head of the Austrian General Staff, Franz Conrad, on a number of occasions pressed for a preventive war. However, he was curbed by the emperor and the archduke. The latter had also opposed the annexation of Bosnia and Clark calls him “the most formidable obstacle to an [Austrian] war policy.” The foreign minister, Leopold von Berchtold, was a part of the heir-apparent’s pro-peace camp.

Clark develops in detail the evolution of the two combinations that faced each other in 1914, the Triple Entente and the Central Powers (what remained of the Triple Alliance, before the defection of Italy, which ultimately became a wartime ally of the Entente).

Back in the 1880s, the German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck had fashioned a series of treaties with Russia and Austria designed to keep a revanchist France isolated. With Bismarck’s dismissal in 1890, the Reinsurance Treaty with Russia was allowed to lapse. Clark breaks with older views in holding that this wasn’t the result of recklessness on the part of the new kaiser, Wilhelm II, but rather the studied decision of inexperienced officials at the Foreign Ministry.

Hitherto friendless, France eagerly embraced a powerful new friend. In 1894 the Franco-Russian Alliance was formed (it was in effect in 1914). One of the treaty’s provisions stated that in the event of mobilization by any member of the Triple Alliance, France and Russia would mobilize all their forces and deploy them against Germany.

French diplomacy, directed by Theophile Delcasse, continued to be brilliant. After settling colonial differences with England, an Entente Cordiale (Cordial Understanding) was concluded between the two western powers.

Edward Grey was foreign secretary and the leader of the anti-German faction in the cabinet. Germany he viewed as an “implacable foe.” He was seconded by Eyre Crowe, a key figure in the Foreign Office, whose influential memorandum of 1907 lamented the titanic growth of German industrial power.

Delcasse joined his two allies together: England and Russia settled their own colonial differences, and combined in a treaty in 1907. The Triple Entente was complete.

The Germans, face to face with three world empires and with only Austria as an ally, complained bitterly of their Einkreisung (encirclement). Perhaps they had a point.

Clark also deviates from the mainstream in demoting the naval race as a critical factor in British antagonism. London never took Wilhelm’s grandstanding about his ocean-going navy seriously. The British always knew they could outbuild the Germans, which they did.

Russia’s disastrous defeat in the war with Japan, 1904-05, served to divert Russian expansion westwards, to the Balkans.

During the approach to war, in the western democracies public opinion was a negligible factor. The people simply did not know. When in 1906 British and French military leaders agreed that in the event of a Franco-German conflict British forces would be sent to the continent, this was not revealed to the people. “The French commitment to a coordinated Franco-Russian military strategy” was also hidden from the French public. So much for democracy.

It was the Italian attack on the Turks in Libya, encouraged by the Entente powers, that sent the dominoes falling. The small Christian nations formed the Balkan League, promoted by Russia, aimed against both the Ottomans and Austria, with Serbia in the lead. Serbian advances electrified aristocratic and bourgeois Russia but angered Austria. With the threat to Serbia, “Russia’s salient in the Balkans,” the Russians mobilized on the Austrian frontier. It was the first mobilization by a great power in the years before the war.

That crisis was defused, but the lines of French policy were stiffened. Poincare, foreign minister and premier, “reassured the Russians that they could count on French support in event of a war arising from an Austro-Serb quarrel.” Similarly, Alexandre Millerand, war minister, told the Russian military attaché that France was “ready” for any further Austrian interference with Serbian rights. Further French loans helped build strategic Russian railroads, heading west. Even the Belgian ambassador to Paris saw Poincare’s policies as “the greatest peril for peace in today’s Europe.”

As 1914 opened, the chances of avoiding war seemed dim. The peacetime strength of the Russian army was 300,000 more than the German and Austrian armies combined, not to count the French. What could Germany do in the event of a two-front war?

All the powers had contingency plans if war came. The German plan, concocted in 1905, was the Schlieffen plan, named for the chief of the Prussian General Staff. It mandated a strong thrust into France, considered the more vulnerable partner, and, after neutralizing French forces, a shuttling of the army to the east to meet the expected Russian incursion into eastern Prussia. Since everything in the plan depended on speed, it was deemed necessary to attack through Belgium.

Back in central Europe, it was clear that Austria had to do something about the murder of the imperial couple. An ultimatum to Serbia was prepared and sent on July 23, more than four weeks after the murders. The delay, partly due to Austria-Hungary’s cumbersome constitutional machinery when it came to foreign policy, partly to the Dual Monarchy’s traditional Schlamperei (slovenliness), served to cool the widespread European indignation over the assassinations.

The provisions that most irked the Serbians were points 5 and 6: that a mixed committee of Austrians and Serbians investigate the crime and that the Austrians participate in apprehending and prosecuting the suspects.

It was a farce on both sides. Austria was looking for a pretext for war. This was the sixth atrocity in four years, and amid unrelenting irredentist agitation Vienna was determined on the final solution of the Serb question.

For their part, the Serbian government knew that any investigation would lead to the critical complicity of its own officials and swing European opinion in the enemy’s direction. It was imperative that Austria be seen to be the aggressor. So after all that had happened, Clark maintains, the Serbian response “offered the Austrians amazingly little.”

Edward Grey, however, held that Austria had no reason for complaint. He bought the Serbian argument that the government was not responsible for the actions of “private individuals,” and that the ultimatum represented a violation of the rights of a sovereign state.

On July 28 Franz Josef signed the declaration of war against Serbia. Foreign Minister Sazonov refused even to listen to the Austrian ambassador’s evidence of Serbian complicity. He had denied from the start “Austria’s right to take action of any kind” (emphasis in Clark). The Tsar expressed his view that the impending war provided a good chance of partitioning Austria, and that if Germany chose to intervene, Russia would “execute the French military plans” to defeat Germany as well.

The Imperial Council issued orders for “Period Preparatory to War” all across European Russia, including against Germany. Even the Baltic Fleet was to be mobilized. At first the Tsar got cold feet, signed on only to partial mobilization, against Austria. Importuned by his ministers hungry for the war that would make Russia hegemonic in central and eastern Europe, he reversed himself again, and finally. As Clark notes, “full [Russian] mobilization must of necessity trigger a continental war.”

On August 1, the German ambassador, Portales, called on Sazonov. After asking him four times whether he would cancel general mobilization and receiving a negative reply each time, Portales presented him with Germany’s declaration of war. The German ultimatum to France was a formality. On August 3, Germany declared war on France as well.

In England, on August 1, Churchill as first lord of the admiralty mobilized the British Home Fleet. Still the cabinet was divided. When Germany presented its ultimatum to Belgium on the next day, Grey had his case complete. Though Belgian neutrality had only been guaranteed by the powers collectively and Italy refused to join in, Grey argued that England nevertheless had a binding moral commitment to Brussels. As for France, he explained that the detailed conversations between their two military leaderships over the years had created understandable French expectations that could not be ignored.

This persuaded the waverers, who were also fearful of the possible resignations of Grey and Asquith. Such a move might well bring to power the Conservatives, even more desirous of war. Seeing the writing on the wall, the few remaining anti-interventionists, led by John Morley, resigned. It was the last act of authentic English liberalism. Lord Morley, the biographer of Cobden and Gladstone, was the author of the tract On Compromise, on the need for principle in politics. On August 4, Britain declared war on Germany.

Warmongers in Paris, St. Petersburg, and London were ecstatic. Churchill beamed, “I am geared up and happy.” But Clark demolishes another myth, that of the delirious throngs. “In most places and for most people” the news of general mobilization came as “a profound shock.” Especially in the countryside, where many of the soldiers would perforce be drawn from. Peasants and peasants’ sons would furnish the cannon fodder, much of it in France and Germany, the vast bulk of it in Austria-Hungary and Russia. In tens of villages there reigned “a stunned silence,” broken only by the sound of “men, women, and children” weeping.

It was into this Witches’ Sabbath that, from 1914 on, Woodrow Wilson slowly but steadily led the unknowing American people.

The Best of Ralph Raico

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

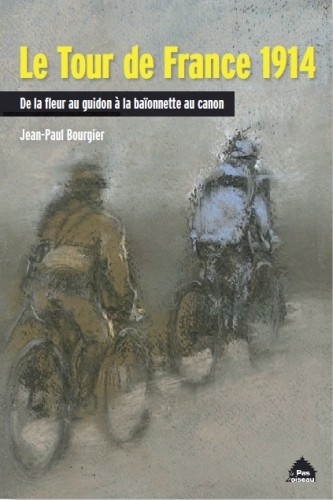

La Coupe du monde de football vient de se terminer; les amateurs de sports tournent leur regard, comme chaque mois de juillet, vers le Tour de France cycliste. La plus célèbre course de vélos du monde se déroule aujourd'hui à l'ombre de celle de 1914, cent ans après que la première guerre mondiale ait éclaté. Le départ d'une étape à Ypres, le passage du peloton le long du champ de bataille de Verdun, les longues étapes en Alsace et en Lorraine en sont la preuve. L'étape qui s'est déroulée sur les pavés du Nord a été, elle aussi, un hommage aux morts de la première guerre mondiale, parce que l'expression "l'enfer du Nord" est née en 1919, quand le parcours de la course Paris-Roubaix était particulièrement sinistre et difficile. Les voies "carrossables" avaient été labourées par les artilleries française, britannique et allemande.

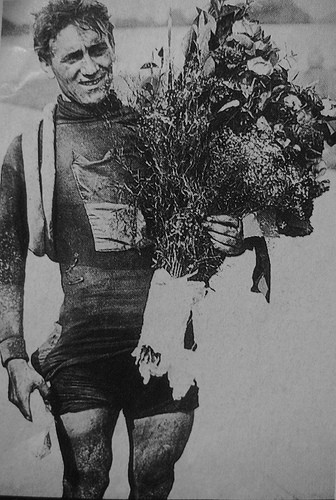

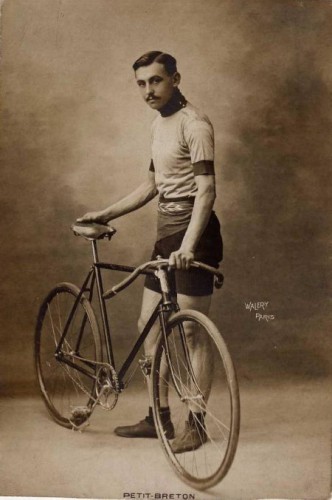

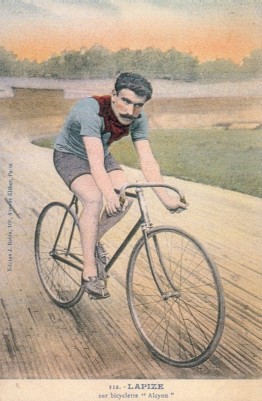

La Coupe du monde de football vient de se terminer; les amateurs de sports tournent leur regard, comme chaque mois de juillet, vers le Tour de France cycliste. La plus célèbre course de vélos du monde se déroule aujourd'hui à l'ombre de celle de 1914, cent ans après que la première guerre mondiale ait éclaté. Le départ d'une étape à Ypres, le passage du peloton le long du champ de bataille de Verdun, les longues étapes en Alsace et en Lorraine en sont la preuve. L'étape qui s'est déroulée sur les pavés du Nord a été, elle aussi, un hommage aux morts de la première guerre mondiale, parce que l'expression "l'enfer du Nord" est née en 1919, quand le parcours de la course Paris-Roubaix était particulièrement sinistre et difficile. Les voies "carrossables" avaient été labourées par les artilleries française, britannique et allemande.  Les médias ont consacré quelques minutes d'attention aux vainqueurs du Tour avant 1914 (le premier Tour a eu lieu en 1903), qui n'ont pas survécu à la première guerre mondiale. Ainsi, Lucien Petit-Breton, vainqueur en 1907 et en 1908, le Luxembourgeois François Faber, vainqueur en 1909, et Octave Lapize, vainqueur en 1910. Petit-Breton a eu une fin misérable: courrier dans l'armée française, il a été renversé par une calèche menée par un cocher ivre. On n'a jamais retrouvé de traces du Luxembourgeois Faber, engagé dans la Légion Etrangère. Il combattait dans la région de la Somme et a disparu le 9 mai 1915 lors d'un combat à proximité d'Arras. Lapize, peut-on dire, a eu la mort du héros: pilote d'un avion de reconnaissance de la toute jeune aviation française, il a été abattu le 14 juillet 1917 en Lorraine.

Les médias ont consacré quelques minutes d'attention aux vainqueurs du Tour avant 1914 (le premier Tour a eu lieu en 1903), qui n'ont pas survécu à la première guerre mondiale. Ainsi, Lucien Petit-Breton, vainqueur en 1907 et en 1908, le Luxembourgeois François Faber, vainqueur en 1909, et Octave Lapize, vainqueur en 1910. Petit-Breton a eu une fin misérable: courrier dans l'armée française, il a été renversé par une calèche menée par un cocher ivre. On n'a jamais retrouvé de traces du Luxembourgeois Faber, engagé dans la Légion Etrangère. Il combattait dans la région de la Somme et a disparu le 9 mai 1915 lors d'un combat à proximité d'Arras. Lapize, peut-on dire, a eu la mort du héros: pilote d'un avion de reconnaissance de la toute jeune aviation française, il a été abattu le 14 juillet 1917 en Lorraine. Le hasard a voulu que le Tour de 1914 ait commencé le 28 juin, le jour même où l'héritier du trône impérial austro-hongrois et son épouse la Comtesse Sophie Chotek ont été assassinés à Sarajevo par l'activiste Gavrilo Princip. Cet assassinat a été le coup d'envoi de la première grande conflagration mondiale mais on ne l'imaginait pas encore quand le départ du Tour a été donné. Pendant la première étape, d'Abbeville au Tréport, personne n'a songé aux événements qui venaient de marquer l'Empire austro-hongrois.

Le hasard a voulu que le Tour de 1914 ait commencé le 28 juin, le jour même où l'héritier du trône impérial austro-hongrois et son épouse la Comtesse Sophie Chotek ont été assassinés à Sarajevo par l'activiste Gavrilo Princip. Cet assassinat a été le coup d'envoi de la première grande conflagration mondiale mais on ne l'imaginait pas encore quand le départ du Tour a été donné. Pendant la première étape, d'Abbeville au Tréport, personne n'a songé aux événements qui venaient de marquer l'Empire austro-hongrois.  Le Tour de France de 1914 s'est déroulé sans le moindre souci. A Cherbourg, les coureurs se trouvaient dans le même hôtel que la figure de proue du socialisme français, Jean Jaurès, avec qui ils ont plaisanté. Juste avant que n'éclate la guerre, cet homme politique a été assassiné. On pouvait déceler bien des indices prouvant la tension croissante entre puissances européennes mais les coureurs en riaient, en disant que des événements plus graves avaient ponctué la politique internationale au cours des quinze dernières années.

Le Tour de France de 1914 s'est déroulé sans le moindre souci. A Cherbourg, les coureurs se trouvaient dans le même hôtel que la figure de proue du socialisme français, Jean Jaurès, avec qui ils ont plaisanté. Juste avant que n'éclate la guerre, cet homme politique a été assassiné. On pouvait déceler bien des indices prouvant la tension croissante entre puissances européennes mais les coureurs en riaient, en disant que des événements plus graves avaient ponctué la politique internationale au cours des quinze dernières années.

En ce début 2014, la France s’apprête à célébrer le centenaire du plus grand attentat-suicide de son histoire, de l’immense, de la monstrueuse, de l’imbécile tuerie de masse qui marqua le début de son déclin et la fin de l’hégémonie européenne sur le monde. De pieux discours, des cérémonies devant les monuments aux morts, des défilés, des reconstitutions, des livres et des films commémoreront le sacrifice de notre jeunesse, l’héroïsme de nos poilus, la gloire de nos grands-pères, et l’on rendra l’hommage rituel, sinon aux « grands chefs » de nos armées qui n’ont plus tellement la cote, du moins aux deux principaux fauteurs français de l’hécatombe : Poincaré, qui présida à la déclaration de guerre, Clemenceau qui, avec une obstination sénile, la fit jusqu’au bout avec le sang des autres et concourut, avec le traité de Versailles, à mettre au point le détonateur de l’explosion à venir.

En ce début 2014, la France s’apprête à célébrer le centenaire du plus grand attentat-suicide de son histoire, de l’immense, de la monstrueuse, de l’imbécile tuerie de masse qui marqua le début de son déclin et la fin de l’hégémonie européenne sur le monde. De pieux discours, des cérémonies devant les monuments aux morts, des défilés, des reconstitutions, des livres et des films commémoreront le sacrifice de notre jeunesse, l’héroïsme de nos poilus, la gloire de nos grands-pères, et l’on rendra l’hommage rituel, sinon aux « grands chefs » de nos armées qui n’ont plus tellement la cote, du moins aux deux principaux fauteurs français de l’hécatombe : Poincaré, qui présida à la déclaration de guerre, Clemenceau qui, avec une obstination sénile, la fit jusqu’au bout avec le sang des autres et concourut, avec le traité de Versailles, à mettre au point le détonateur de l’explosion à venir.