Jonathan BOWDEN

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

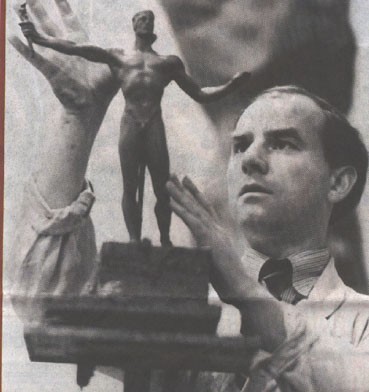

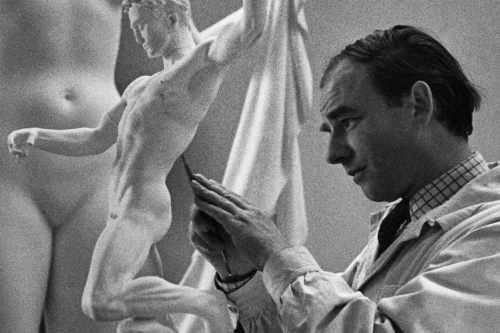

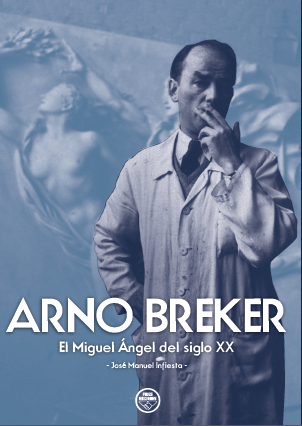

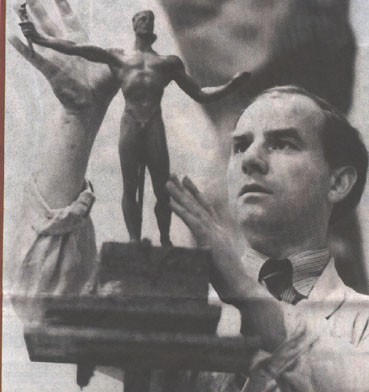

Arno Breker (1900–1991) was the leading proponent of the neo-classical school in the twentieth century, but he was not alone by any stretch of the imagination. If we gaze upon a great retinue of his figurines, which can be seen assembled in the Studio at Jackesbruch (1941), then we can observe images such as Torso with Raised Arms (1929), the Judgment of Paris, St. Mathew (1927), and La Force (1939). All of these are taken from the on-line museum and linkage which is available at:

http://ilovefiguresculpture.com/masters/german/breker/bre...

The real point to make is that these are dynamic pieces which accord with over three thousand years of Western effort. They are not old-fashioned, Reactionary, bombastic, “facsimiles of previous glories,” mere copies or the pseudo-classicism of authoritarian governments in the twentieth century (as is usually declared to be the case). Joseph Stalin approached Breker after the Second European Civil War (1939–1945) in order to explore the possibility for commissions, but insisted that they involved castings which were fully clothed. At first sight, this was an odd piece of Soviet prudery — but, in fact, politicians as diverse as John Ashcroft (Bush’s top legal officer) and Tony Blair refused to be photographed anywhere near classical statuary for fear that any proximity to nudity (without Naturism) might lead to their tabloid down-fall.

All of Breker’s pieces have precedents in the ancient world, but this has to be understood in an active rather than a passive or re-directed way. If we think of the Hellenism which Alexander’s all-conquering armies inspired deep into Asia Minor (and beyond), then pieces like the Laocoön at the Vatican or the full-nude portrait of Demetrius the First of Syria, whose modelling recalls Lysippus’ handling, are definite precursors. (This latter piece is in the National Museum in Rome.) Yet Breker’s work is quite varied, in that it contains archaic, semi-brutalist, unshorn, martial relief and post-Cycladic material. There is also the resolution of an inner tension leading to a Stoic calm, or a heroic and semi-religious rest, that recalls the Mannerist art of the sixteenth century. Certain commentators, desperate for some sort of affiliation to modernism in order to “save” Breker, speak loosely of Expressionist sub-plots. This is quite clearly going too far — but it does draw attention to one thing . . . namely, that many of these sculptures indicate an achievement of power, a rest or beatitude after turmoil. They are indicative of Hemingway’s definition of athletic beauty — that is to say, grace under pressure or a form of same.

All of Breker’s pieces have precedents in the ancient world, but this has to be understood in an active rather than a passive or re-directed way. If we think of the Hellenism which Alexander’s all-conquering armies inspired deep into Asia Minor (and beyond), then pieces like the Laocoön at the Vatican or the full-nude portrait of Demetrius the First of Syria, whose modelling recalls Lysippus’ handling, are definite precursors. (This latter piece is in the National Museum in Rome.) Yet Breker’s work is quite varied, in that it contains archaic, semi-brutalist, unshorn, martial relief and post-Cycladic material. There is also the resolution of an inner tension leading to a Stoic calm, or a heroic and semi-religious rest, that recalls the Mannerist art of the sixteenth century. Certain commentators, desperate for some sort of affiliation to modernism in order to “save” Breker, speak loosely of Expressionist sub-plots. This is quite clearly going too far — but it does draw attention to one thing . . . namely, that many of these sculptures indicate an achievement of power, a rest or beatitude after turmoil. They are indicative of Hemingway’s definition of athletic beauty — that is to say, grace under pressure or a form of same.

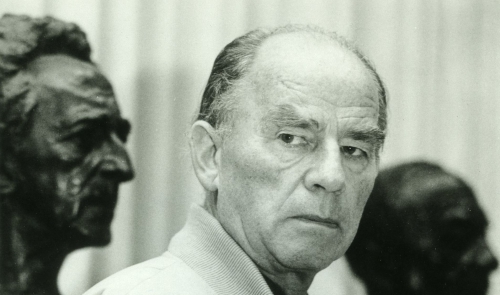

This is quite clearly missed by the well-known interview between Breker and Andre Muller in 1979 in which a Rottweiler of the German press (of his era) attempts to spear Breker with post-war guilt. Indeed, at one dramatic moment in the dialogue between them, Muller almost breaks down and accuses Breker of producing necrophile masterpieces or anti-art (sic). What he means by this is that Breker is artistically glorifying in war, slaughter, and death. As a Roman Catholic teacher of acting once remarked to me, concerning the poetry of Gottfried Benn, it begins with poetry and ends in slaughter. Yet the answer to this ethical ‘plaint is that it was ever so. Artistic works have always celebrated the soldierly virtues, the martial side of the state and its prowess, and all of the triumphalist sculpture on the Allied side (American, Soviet, Resistance-oriented in France, etc. . . .) does just that. As Wyndham Lewis once remarked in The Art of Being Ruled, the price of civility in a cultivated dictatorship (he was thinking of Mussolini’s Italy) might well be the provision of an occasional Gladiator in pastel . . . so that one could be free from communist turmoil, on the one hand, and able to continue one’s work in serenity, on the other. Doesn’t Hermann Broch’s great post-modern work, The Death of Virgil, which dips in and out of Virgil’s consciousness as he dies, rather like music, not speculate on his subservience to the Caesars and his pained confusion about whether the Aeneid should be destroyed? It survived intact.

Nonetheless, the interview provides a fascinating crucible for the clash of twentieth century ideas in more ways than one. At one point Muller’s diction resembles a piece of dialogue from a play by Samuel Beckett (say End-Game or Fin de Partie); maybe the stream-of-consciousness of the two tramps in Waiting for Godot. For, whether it’s Vladimir or Estragon, they might well sound like Muller in this following exchange. Muller indicates that his view of Man is broken, crepuscular, defeated, incomplete and misapplied — he congenitally distrusts all idealism, in other words. Mankind is dung — according to Muller — and coprophagy the only viable option. Breker, however, is of a fundamentally optimistic bent. He avers that the future is still before us, his Idealism in relation to Man remains unbroken and that a stratospheric take-off into the future remains a possibility (albeit a distant one at the present juncture).

Another interesting exchange between Muller and Breker in this interview concerns the Shoah. (It is important to realise that this highly-charged chat is not an exercise in reminiscence. It concerns the morality of revolutionary events in Europe and their aftermath.) By any stretch, Breker declares himself to be a believer and that the criminal death through a priori malice of anyone, particularly due to their ethnicity, is wrong. At first sight this appears to be an unremarkable statement. A bland summation would infer that the neo-classicist was a believer in Christian ethics, et cetera. . . . Yet, viewed again through a different premise, something much more revolutionary emerges. Breker declares himself to be a “believer” (that is to say, an “exterminationist” to use the vocabulary of Alexander Baron); yet even to affirm this is to admit the possibility of negation or revision (itself a criminal offense in the new Germany). For the most part contemporary opinion mongers don’t declare that they believe in Global warming, the moon shot, or the link between HIV and AIDS — they merely affirm that no “sane” person doubts it.

Another interesting exchange between Muller and Breker in this interview concerns the Shoah. (It is important to realise that this highly-charged chat is not an exercise in reminiscence. It concerns the morality of revolutionary events in Europe and their aftermath.) By any stretch, Breker declares himself to be a believer and that the criminal death through a priori malice of anyone, particularly due to their ethnicity, is wrong. At first sight this appears to be an unremarkable statement. A bland summation would infer that the neo-classicist was a believer in Christian ethics, et cetera. . . . Yet, viewed again through a different premise, something much more revolutionary emerges. Breker declares himself to be a “believer” (that is to say, an “exterminationist” to use the vocabulary of Alexander Baron); yet even to affirm this is to admit the possibility of negation or revision (itself a criminal offense in the new Germany). For the most part contemporary opinion mongers don’t declare that they believe in Global warming, the moon shot, or the link between HIV and AIDS — they merely affirm that no “sane” person doubts it.

Similarly, even Muller raises the differentiation in Breker’s work over time. This is particularly so after the twin crises of 1945 and 1918 and the fact that these were the twin Golgothas in the European sensibility — both of them taking place, almost as threnodies, after the end of European Civil Wars. Germany and its allies taking the role of the Confederacy on both occasions, as it were. Immediately after the War — and amid the kaos of defeat and “Peace” — Breker produced St. Sebastien in 1948, St. George (as a partial relief) in 1952, and the more reconstituted St. Christopher in 1957. (One takes on board — for all sculptors — the fact that the Church is a valuable source of commissions in stone during troubled times.) All of this led to a celebration of re-birth and the German economic miracle of recovery in his unrealized Resurrection (1969) which was a sketch or maquette to the post-war Chancellor Adenauer. Saint Sebastien is interesting in its semi-relief quality which is the nearest that Breker ever comes to a defeated hero or — quite possibly — the mortality which lurks in victory’s strife. Interestingly enough, a large number of aesthetic crucifixions were produced around the middle of the twentieth century. One thinks (in particular) of Buffet’s post-Christian and existential Pieta, Minton’s painting in the ‘fifties about the Roman soldiery, post-Golgotha, playing dice for Christ’s robes, or Bacon’s screaming triptych in 1947; never mind Graham Sutherland’s reconstitution of Coventry Cathedral (completely gutted by German bombing); and an interesting example of an East German crucifixion.

This is a fascinating addendum to Breker’s career — the continuation of neo-classicism, albeit filtered through socialist realism, in East Germany from 1946–1987. An interesting range of statuary was produced in a lower key — a significant amount of it not just keyed to Party or bureaucratic purposes. In the main, it strikes one as a slightly crabbed, cramped, more restricted, mildly cruder and more “proletarianized” version of Breker and Kolbe. But some decisive and significant work (completely devalued by contemporary critics) was done by Gustav Seitz, Walter Arnold, Heinrich Apel, Bernd Gobel, Werner Stotzer, Siegfried Schreiber, and Fritz Cremer. His crucifixion in the late ‘forties has a kinship (to my mind) with some of Elisabeth Frink’s pieces — it remains a neo-classic form whilst edging close to elements of modernist sculpture in its chthonian power and deliberate primitivism. A part of the post-maquette or stages of building up the Form remains in the final physiology, just like Frink’s Christian Martyrs for public display. Perhaps this was the nearest a three-dimensional artist could get to the realization of religious sacrifice (tragedy) in a communist state.

Anyway, and to bring this essay to a close, one of the greatest mistakes made today is the belief that the Modern and the Classic are counterposed, alienated from one another, counter-propositional and antagonistic. The Art of the last century and a half is an enormous subject (it’s true) yet Arno Breker is one of the great Modern artists. One can — as the anti-humanist art collector Bill Hopkins once remarked — be steeped both in the Classic and the Modern. Living neo-classicism is a genuine contemporary tradition (post Malliol and Rodin) because photography can never replace three-dimensionality in form or focus. Above all, perhaps it’s important to make clear that Breker’s work represents extreme heroic Idealism . . . it is the fantastication of Man as he begins to transcend the Human state. In some respects, his work is a way-station towards the Superman or Ultra-humanite. This remains one of the many reasons why it sticks in the gullet of so many liberal critics!

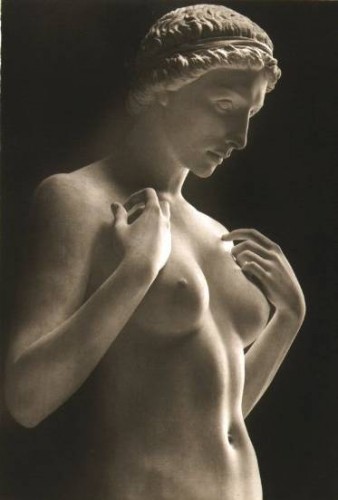

One will not necessarily reassure them by stating that Breker’s monumental sculptures during his phase of Nazi Art were modeled (amongst other things) on the Athena Parthenos. The original was over forty feet high, came constructed in ivory and gold, and was made during the years 447–439 approximately. (The years relate to Before the Common Era, of course.) The Goddess is fully armoured — having been born whole as a warrior-woman from Zeus’ head. There may be Justice but no pity. A winged figure of Victory alights on her right-hand; while the left grasps a shield around which a serpent (knowledge) writhes aplenty. A re-working can be seen in John Barron’s Greek Sculpture (1965), but perhaps the best thing to say is that the heroic sculptor of Man’s form, Steven Mallory, in Ayn Rand’s Romance The Fountainhead is clearly based on Thorak: Breker’s great rival. Yet the “gold in the furnace” producer of a Young Woman with Cloth (1977) remains to be discovered by those tens of thousands of Western art students who have never heard of him . . . or are discouraged from finding out.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Op dat moment toekomstig Minister van Propaganda Joseph Goebbels, die Breker in Rome had leren kennen, drong er bij hem op aan om terug te keren naar Duitsland, omdat “er hem een grote toekomst te wachten stond”. De jonge en ambitieuze Breker aarzelde niet, zeker niet toen schilder en goede vriend Max Lieberman hem daar ook nog eens toe aanzette. In 1934 keerde Breker terug naar zijn vaderland, waar hij alle voordelen genoot van een protegé van het regime.

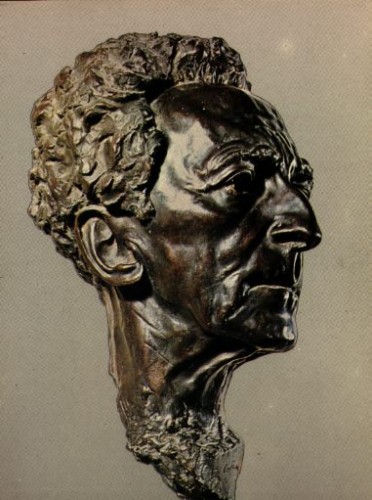

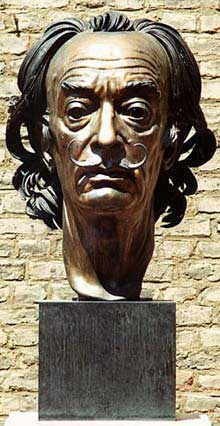

Op dat moment toekomstig Minister van Propaganda Joseph Goebbels, die Breker in Rome had leren kennen, drong er bij hem op aan om terug te keren naar Duitsland, omdat “er hem een grote toekomst te wachten stond”. De jonge en ambitieuze Breker aarzelde niet, zeker niet toen schilder en goede vriend Max Lieberman hem daar ook nog eens toe aanzette. In 1934 keerde Breker terug naar zijn vaderland, waar hij alle voordelen genoot van een protegé van het regime. De eerste jaren na het einde van Wereldoorlog II leefde Breker nogal teruggetrokken. Hij maakte van de tijd, die hij afgezonderd was, wel gebruik om na te denken over zijn leven, de keuzes die hij gemaakt had enz. en om opnieuw contact te zoeken met zijn oude (Franse) vrienden, collega’s. Pas sinds de jaren 1950 liepen de opdrachten terug binnen. Deze opdrachten waren vooral inzake schilderijen, bustes (bijvoorbeeld van de Italiaanse dichter Ezra Pound en de Spaanse kunstenaar Salvador Dali) en zelfs enkele architecturale opdrachten (bijvoorbeeld het Gerling-gebouw in Keulen).

De eerste jaren na het einde van Wereldoorlog II leefde Breker nogal teruggetrokken. Hij maakte van de tijd, die hij afgezonderd was, wel gebruik om na te denken over zijn leven, de keuzes die hij gemaakt had enz. en om opnieuw contact te zoeken met zijn oude (Franse) vrienden, collega’s. Pas sinds de jaren 1950 liepen de opdrachten terug binnen. Deze opdrachten waren vooral inzake schilderijen, bustes (bijvoorbeeld van de Italiaanse dichter Ezra Pound en de Spaanse kunstenaar Salvador Dali) en zelfs enkele architecturale opdrachten (bijvoorbeeld het Gerling-gebouw in Keulen).