mardi, 03 décembre 2013

The Language of Manliness

Unless you regularly read this blog, you may never have heard someone use the word manliness in writing or conversation. Ditto for manly, unless it was said a bit in jest and with the requisite eye roll. And you almost assuredly have never complimented another dude on his manful effort.

These days man is generally only used to designate a person’s gender. There was a time, however, where man – and its many grammatical derivatives – represented a distinct trait and quality, and was employed as a descriptive adjective and adverb.

In our research on manliness over the years, it has been interesting to see the different words that were used to call out a true man and the behaviors befitting a man, and how those words have changed and in some cases disappeared over time. Today we’ll take a look at some of those words and what they used to mean.

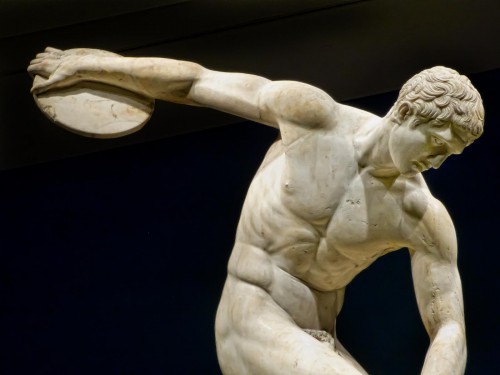

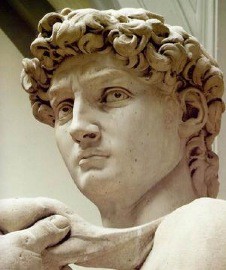

The Title of Man in the Ancient World

Mention the word manliness these days and you’ll probably be greeted with snorts and giggles; people have told me that the first time they visited this site, they thought it was a joke. Many people today associate manliness with cartoonish images of men sitting in their man caves, drinking beer and watching the big game. Or, just as likely, they don’t think much about manliness at all, chalking it up to the mere possession of a certain set of genitalia. Whatever image they have in mind when you mention manliness, it isn’t usually positive, and it probably has nothing to do with virtue.

Yet for over two thousand years, many of the world’s great thinkers explored and celebrated the subject of manliness, imagining it not as something silly or biologically inherent, but as the culmination of certain virtues as expressed in the life of a man.

The ancient Greek word for courage – andreia – literally meant manliness. Courage was considered the sin qua non of being a man; the two qualities were inextricably linked. The Greeks primarily thought of andreia in terms of valor and excellence on the battlefield. A man with courage was strong and bold, with a white hot thumos. They believed that to attain full arête – or excellence – a man should join courage with other cardinal virtues like wisdom, justice, and temperance. But, they also acknowledged that men who were unjust and unwise could still be fiercely courageous – and manly. At the same time, many philosophers argued that courage was really a form of self-control and was just as essential for success in peacetime as it was in war. Aristotle for example broadly described courage as a man’s ability to “hold fast to the orders of reason about what he ought or ought not to fear in spite of pleasure and pain.”

The Roman word for man – vir – was very similar in definition to the Greek andreia. Vir was strongly associated with courage, particularly of the martial variety. In the latter part of the Roman era, as excellence became just as necessary in governance as on the battlefield, the traits associated with being a man worthy of the title vir expanded to include not just courage, but other qualities such as fortitude, industry, and dutifulness. Thus it is from the Latin vir that we get the English word virtue.

Manliness

The next great era of man-centric language was the 19th century. Like the ancient Greeks and Romans, English and American thinkers of that time believed manliness was not an automatic trait of biology but something that had to be earned. Writers and speakers of this period continued the Roman tradition of defining manliness as the possession of a certain set of virtues, adding to the requisite list other qualities befitting a Victorian gentleman:

“Manliness means perfect manhood, as womanliness implies perfect womanhood. Manliness is the character of a man as he ought to be, as he was meant to be. It expresses the qualities which go to make a perfect man, — truth, courage, conscience, freedom, energy, self-possession, self-control. But it does not exclude gentleness, tenderness, compassion, modesty. A man is not less manly, but more so, because he is gentle.”

“For anything worthy of the name of Manliness there must be first…the development of all that is in man—the physical, the mental, the moral, and the spiritual…virtue is the highest quality in a man; and so that manliness is most fully realized where the virtues are most fully developed—the virtues, shall we say, of Bravery, Honesty, Activity, and Piety.”

Men of the 19th and early 20th centuries also saw manliness not simply as a collection of different virtues, but as a virtue in and of itself – a distinct quality. They encouraged men to embrace manliness as the crown of character – as a kind of ineffable bonus power that was produced when all the other virtues were combined (the Captain Planet of the virtues, if you will). Manliness was often noted as a separate, preeminent trait in men worthy of admiration:

Men of the 19th and early 20th centuries also saw manliness not simply as a collection of different virtues, but as a virtue in and of itself – a distinct quality. They encouraged men to embrace manliness as the crown of character – as a kind of ineffable bonus power that was produced when all the other virtues were combined (the Captain Planet of the virtues, if you will). Manliness was often noted as a separate, preeminent trait in men worthy of admiration:

“He is going to be known as a boys’ hero. He is going to be known preeminently for his manliness. There is going to be a Roosevelt legend.”

“I have grieved most deeply at the death of your noble son. I have watched his conduct from the commencement of the war, and have pointed with pride to the patriotism, self-denial, and manliness of character he has exhibited.”

Manliness was often used in a way that seemed to imply that while the quality encompassed all the other virtues, it also acted as a balance to them — ensuring that the softer, gentlemanly virtues didn’t sap a man of a virile toughness:

“After all, the greatest of Washington’s qualities was a rugged manliness which gave him the respect and confidence even of his enemies.”

“We have met to commemorate a mighty pioneer feat, a feat of the old days, when men needed to call upon every ounce of courage and hardihood and manliness they possessed in order to make good our claim to this continent. Let us in our turn with equal courage, equal hardihood and manliness, carry on the task that our forefathers have entrusted to our hands.”

As it was in antiquity, the measure of manliness amongst its citizenry was often linked to the health of the republic:

“Government, as recognized by Democracy, pre-supposes manliness, knowledge, wisdom.”

“We are a vigorous, masterful people, and the man who is to do good work in our country must not only be a good man, but also emphatically a man. We must have the qualities of courage, of hardihood, of power to hold one’s own in the hurly-burly of actual life. We must have the manhood that shows on fought fields and that shows in the work of the business world and in the struggles of civic life. We must have manliness, courage, strength, resolution, joined to decency and morality, or we shall make but poor work of it.”

Manly

The perfect definition for manly can be found in an 1844 Greek and English lexicon, showing as it does a common thread in the understanding of manliness that runs from antiquity, through the 19th century, and up to how we employ the descriptor on AoM in the present day:

“Pertaining to a man, masculine; manly; suiting, fit for, becoming a man, or made use of by, as manners, dress, mode of life; suiting, or worthy of a man, as to action, conduct or sentiments, and thus, manly, vigorous, brave, resolute, firm.”

Our forbearers used manly to modify a whole host of behaviors, traits, and objects. An admirable man might be said to possess “manly courage,” which was shown by exhibiting “manly conduct,” making a “manly stand,” and holding on to his “manly independence.” Jefferson believed it was the “manly spirit” of his countrymen that led to revolution. If others did not respect your desire for “manly liberty,” you had to resort to wielding a “manly sword.” Correspondence that was frank in its contents was held up as a “manly letter.” Dress that made a young man seem more mature was advertised as a “manly suit.” Keeping things “simple and on point” might get you complimented for your “manly speech,” while being “candid,” “unaffected,” and “forcible” would earn you praise for a “manly delivery.” How you carried yourself mattered too; George Washington, for one, was described as having “a fine, manly bearing” and men talked about the elements of a “manly handshake” long before we did. And a boy who precociously sought to embody the traits of manliness was considered a “manly boy.”

Manful

Manful (or manfully) was sometimes used in a similar way as manly. But there were some shades of difference between the two descriptors, even if people weren’t always sure exactly what those differences were. 1871’s Synonyms Discriminated, argued that:

“MANFUL is commonly applied to conduct; MANLY, to character. Manful opposition; manly bravery. Manful is in accordance with the strength of a man; manly, with the moral excellence of a man. Manful is what a man would, as such, be likely to do; manly, what he ought to do, and to feel as well.”

Another lexicographer put it this way:

“Manful points to the energy and vigor of a man; manly, to the generous and noble qualities of a man. The first is opposed to weakness or cowardice, the latter to that which is puerile or mean. We speak of manful exertion without so much reference to the character of the thing for which exertion is made, but manly conduct is that which has reference to a thing worthy of a man.”

English Synonyms Explained saw the difference from another angle:

“MANLY, or like a man, is opposed to juvenile, and of course applied properly to youths; but MANFUL, or full of manhood, is opposed to effeminate, and is applicable more properly to grown persons.”

In practice, authors seemed not to have followed either of these usage rules – and manly and manful were employed fairly interchangeably. Manfully came in handy for when an adverb was needed to note the manful-ness of an action. But as manful appears in old texts much less frequently than manly, and is far less familiar to the modern reader, one can likely assume that the confusion of when to use which led to the latter supplanting the former as the catch-all for behaviors and actions befitting a man.

Unmanned

The code of honor for a man of the 19th century included many qualities, principal among which was self-control. A man of this time strived to have a stiff upper lip and be calm and cool even under the most trying of circumstances.

To lose one’s self-control was to lose one’s claim to manhood, and thus men of this time described such a slip as being unmanned. One dictionary of the time defined unmanned as “deprived of the powers and qualities of a man. Softened.” The term was frequently used in reference to a man’s giving in to a strong emotional reaction:

“When told that his recovery was hopeless, he was perfectly unmanned, and wept like a child. It is here introduced as showing that while his own misfortunes never for a single moment disturbed his equanimity, the finer feelings of his nature were sensitively alive to the distresses of others.”

“Richard turned to stay the torrent of invectives, in which such words as “renegades,” “traitors,” “mud-sills,” were heard, but the colonel, completely unmanned by the rage he was in, and seemingly unconscious of the presence of the ladies, waved him aside with his hand, and faced the row of frightened, expectant faces.”

A man whose courage failed him could be said to have been “unmanned by terror.” Or if he drank to the point of losing self-control, he might say the liquor had unmanned him.

One of the most poignant tales of a famous man admitting to being unmanned comes from Abraham Lincoln. One of the first deaths in the Civil War – Elmer Ellsworth — was a close friend of the president. Right after receiving news of Ellsworth’s death, a reporter and Senator came into the White House library to speak with Lincoln. Upon entering, they saw him gazing mournfully out the window at the Potomac. He abruptly turned around, stuck out his arm, and said, “Excuse me, but I cannot talk.” He then burst into tears and began walking around the room, holding a handkerchief to his face as he cried. The two visitors were unsure of what to do; as the reporter later remembered, they were “moved at such an unusual spectacle, in such a man, in such a place.” After several minutes, the president turned to them and said, “I make no apology gentlemen, for my weakness, but I knew poor Ellsworth well, and held him in high regard. Just as you entered the room, Captain Fox left me, after giving me the painful details of his unfortunate death. The event was so unexpected, and the recital so touching, that it quite unmanned me.” Lincoln then “made a violent attempt to restrain his emotion” before sharing the details of his friend’s death.

One of the most poignant tales of a famous man admitting to being unmanned comes from Abraham Lincoln. One of the first deaths in the Civil War – Elmer Ellsworth — was a close friend of the president. Right after receiving news of Ellsworth’s death, a reporter and Senator came into the White House library to speak with Lincoln. Upon entering, they saw him gazing mournfully out the window at the Potomac. He abruptly turned around, stuck out his arm, and said, “Excuse me, but I cannot talk.” He then burst into tears and began walking around the room, holding a handkerchief to his face as he cried. The two visitors were unsure of what to do; as the reporter later remembered, they were “moved at such an unusual spectacle, in such a man, in such a place.” After several minutes, the president turned to them and said, “I make no apology gentlemen, for my weakness, but I knew poor Ellsworth well, and held him in high regard. Just as you entered the room, Captain Fox left me, after giving me the painful details of his unfortunate death. The event was so unexpected, and the recital so touching, that it quite unmanned me.” Lincoln then “made a violent attempt to restrain his emotion” before sharing the details of his friend’s death.

Modern Day: Man Up!

While words like manliness and manful have fallen out of favor in our modern age, our current culture does have its own usages of man-related language.

Man is sometimes tacked on to words to show that they are made for men or have a particularly manly slant, e.g., man purse. Or man is merged into the word itself, such as mancation. Some of these uses are faintly ridiculous, but I’m not above using them myself when I feel it’s appropriate or makes a worthy new word. I quite like the word manvotional for a piece of text that will inspire a man’s spirit, and using a phrase like man room avoids the man-as-Neanderthal connotations of man cave while more succinctly describing a room in which many different manly activities might take place, without having to list out “study, garage, workshop, library…”

But perhaps the dominant man-related term of our modern times is man up. I had always sort of assumed that this now-ubiquitous exhortation was of a somewhat older vintage – that maybe it was coined mid-twentieth century, and had simply been widely discovered and popularized in the last decade or so. But a search for the phrase in Google Books, limited to the 19th and 20th centuries, turned up no results, except for an archaic use of manning up as a term for staffing positions at a business. A search of the archives from the twenty-first century, however, turned up hundreds of books that included the phrase, among which were at least two dozen that used the imperative in the title itself.

Ben Zimmer, author of the “On Language” column at The New York Times, traces the origin of man up back to the 1980s and American football. It was first used in reference to the man-to-man pass defense. For example, in 1985, New York Jets head coach Joe Walton lauded his D-line and their coach for “playing the kind of defense that I wanted and that Bud Carson teaches — aggressive, man up, getting after it, hustling all over the field.” From there the phrase began to take on a more metaphorical cast – as an exhortation to get tough and go hard. The earliest example Zimmer found of this kind of usage is a quote from San Diego Chargers defensive tackle Mike Charles, who told The Union Tribune in 1987: “Right now, by the grace of God, we’re hanging by the skin of our teeth. Now we’ve got to man up and take care of ourselves.”

Man up soon became part of the lingo in another all-male organization that put a premium on grit and strength: the military. Soldiers used it to exhort their brothers-in-arms to pull their weight – as an admonishment to give their best and not become the weak link in the unit.

Thus man up began as an imperative used in male honor groups; born of the reality that each man had a role to play in contributing to the overall strength of the team or unit, it was a man-to-man call to live up to the standards of the group and not let each other down. But as man up gained in usage in the popular culture, it started being used in a variety of contexts – often by women or feminist organizations seeking to tap into the traditional mechanics of honor and shame in an attempt to motivate men to adopt certain behaviors. For example the “Man Up Campaign” is a “global movement” which aims to “end gender-based violence and advance gender equality.” There was also a bit of brouhaha during the most recent Nevada senatorial race when female Republican candidate Sharron Angle told Senator Harry Reid to “Man up!” during a debate. The implication was that Harry Reid was less than a man because he lacked a backbone. The problem when women tell men to “man up!” is that there isn’t really an equally shame-inducing phrase that men can level at women that implies the same thing but won’t get the man criticized for being sexist or patronizing. “Woman up!” just doesn’t sound right (there’s a reason for that). I’ve heard the phrase “put on your big girl panties” said by other women, but if that were to come from a man, it would not likely be received very well!

The road to manliness is paved with…hair gel?

Man up has also been distanced from its origins by being used as a chastisement for those who run afoul of the superficial violations of the “Bro Code.” Advertisers, which have always used shame to sell products, have recently taken to using man up to market their wares as the manly choice. For example, Miller Lite ran a recent campaign that revolved around hot female bartenders shaming men for their ambivalence as to which light beer brand was best, as well as the man’s unforgivably effeminate fashion accessories.

There was even an ABC sitcom called Man Up in 2011 which revolved around the “hilarious” antics of a group of man-children. With super cool and relevant episode titles like “Finessing the Bromance,” it was surprisingly canceled after only 8 episodes.

Man up has become so cliché and meaningless, I’ve stopped using it myself and on AoM altogether.

Conclusion

Describing positive virtues and actions displayed by men as manly or manful has gone out of vogue because of our society’s increasing emphasis on gender neutrality. While I agree that both men and women can strive to be courageous, resolute, and disciplined, I think there’s something to be said about qualifying a virtue or action as manly or manful that inspires men to live up to that ideal. Unlike women, men are (generally) more sensitive to status — particularly to their status in regards to whether they’re a man or not. Most young men want those around them to see them as men and they’ll go to great lengths to conform to the norms their culture and society sets for earning that title.

Many of you might think it’s stupidly archaic that men care about whether they’re manly or not, and they just shouldn’t give a rip. But I’m a pragmatist. Men have always cared about their status as men and probably always will. Even when men say they don’t care about manliness, they usually couch it in a way that shows that they’re actually more manly because they don’t care about being manly! They try to defeat gender normativity with… gender normativity. Hubba-wha?

I’d argue that instead of trying to convince men not to care (which is a losing battle), we’d be better served reviving the classical meaning of these manly descriptors to help inspire men to strive for virtue and excellence. If we want men to be morally courageous and honorable and compassionate, talk about these virtues as being manly courage, manly honor, and manly compassion. You get the idea.

And as we’ve discussed countless times on the site and in our books, I think it’s possible to describe an action or virtue as manly while recognizing that men don’t have a monopoly on these virtues and actions. As ancient literature and writings have shown, both men and women can strive for the same virtues, we just often attain them and express them in different ways.

So here’s to bringing back manly language!

Just don’t get too carried away with it. You don’t have to put manly in front of every damn thing you think is good. That will just ruin it for the rest of us. Use some manly discretion.

Oh yeah, and stay manly.

_______

Editor’s note: All the quotes above, unless otherwise cited, come from various books from the 19th and early 20th centuries. If you’re interested in further reading, they can all be found for free on Google Books.

00:05 Publié dans Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, virilité, virilisme, machisme, macho |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook