In every time period, and all across the world, men have been very interested in the question of what it means to be a man. Some of their answers were learned intuitively by watching their peers and mentors, while other aspects of manliness were taught to them and imparted intentionally and explicitly.

In primitive times, the “secret knowledge” of manhood was passed down from elders to boys in elaborate coming-of-age ceremonies.

In ancient times, philosophers contemplated the virtues and qualities that constituted the attainment of arete — a word meaning “excellence” that was sometimes used interchangeably with andreia or “manliness.”

In our own times, men experience few knowledge-imparting rites of passage, and the meaning of manliness is not often discussed by present-day philosophers. Most unfortunately, the chains of intuitive manhood — the mentor relationships which offer a chance to learn manhood by example — are all too often severed or nonexistent.

As a result, many men are unsure of what it means to be a man — how they’re different from women, why they sometimes act the way they do, and what kinds of virtues and behaviors they need to cultivate in their lives in order to understand who they are, fulfill their potential, and live a satisfying life.

I know when I started the Art of Manliness back in 2008, I had only the foggiest idea of what exactly manliness meant. My ideas had mostly been picked up unconsciously from various streams of popular culture and absorbed without much examination.

In the last 8 years, I’ve dived headfirst into getting an education in the meaning and nature of manhood. I’ve read dozens of books on the biology, psychology, anthropology, and philosophy of masculinity, all in search of developing a multi-faceted answer to the big questions surrounding the male experience: What is manliness and where does it come from? Why is it that we associate aggression, risk-taking, and bravado with manhood? How did past cultures harness the traits of masculinity for good rather than evil?

Most of the books that I’ve read on the subject were okay, but a select few have done a masterful job of explaining the answers to these questions. Below you’ll find the ones I think are the best of the best. They’ve influenced how I approach the topic of manliness on the site immensely and have given me insights into my own life and place in the world. My series on honor, the 3 P’s of manhood, and male status relied heavily on research from these books, and they’re ones I have found myself returning to year after year — often re-reading them only to find new insights.

Some of the books focus on one aspect of manliness, like the evolutionary origins of male physical and psychological traits or how men behave in groups, while others take a big picture approach to looking at manliness as a cultural imperative or a set of virtues. I don’t agree with all the conclusions that most of the authors draw. And that’s okay. It’s good to have your ideas challenged and it’s still possible to get something out of a book even if you don’t end up agreeing with the author’s final thesis.

In a time where ideas about manliness are often fuzzy or contradictory, if they’re even discussed at all, these books give you insights into history, culture, and understanding more about who you are; they’ll help you discover a “secret knowledge” that’s largely been lost in the past several decades. If you’d like to further your understanding of what it means to be a man, give these books a read.

The Way of Men

Arguably the modern classic on masculinity. Jack Donovan works to strip away all the culturally/religiously relative definitions of manhood that exist in order to arrive at the very essentials of what makes men, men. He calls these essentials the “tactical virtues” and they include: strength, courage, mastery, and honor.

While the amoral nature of Donovan’s idea of masculinity may make some uncomfortable, that is in many ways its greatest strength. Whenever my thinking on manhood gets muddled by all the competing definitions and claims out there, I return to The Way of Men to get reacquainted with the very core of masculinity. It’s a short, accessible book, with pithy, muscular prose — there’s really no reason every man shouldn’t read it and consider its forceful and challenging ideas. Once you do, you can take Donovan’s vision of the foundation of masculinity and stop there, or you can add a moral/philosophical layer onto it. For that task, I’d recommend the next book.

Listen to my podcast interview with Jack Donovan.

The Code of Man: Love, Courage, Pride, Family, Country

If the The Way of Men is the book on the biological/anthropological nature of manhood, The Code of Man is the book on the philosophical vision of manhood.

In The Code of Man, Dr. Waller R. Newell argues that modern men have lost touch with the values and virtues that have defined manliness for thousands of years. Consequently, many men (particularly young men) are lost, confused, and angry. Newell believes that the road to recovery is taken along the five paths to manliness: love, courage, pride, family, and country. Using Western writers and thinkers like Aristotle and Plato, Newell attempts to guide men down the path to achieving a “manly heart.”

Newell’s idea of honorable and virtuous manliness is aligned almost perfectly with the conception of manliness that we espouse on AoM. I’ve actually read this book again several times since my initial reading a few years ago and I still find it as stirring and as relevant as the first time I read it.

Listen to my podcast interview with Dr. Waller Newell.

Manhood in the Making: Cultural Concepts of Masculinity

If you enjoyed our 3 P’s of Manhood series, then you’ll want to read the book that inspired it. Manhood in the Making is by far the most enlightening book on manhood I’ve ever read. In it, anthropologist David Gilmore shares the results of his cross-cultural study of manliness around the globe. Gilmore found that the concern for being manly and the idea of being a “real man,” is hardly a culturally-relative, social norm-based phenomenon, but instead has been shared by nearly every culture in the world, both past and present.

While every society’s idea of what constitutes a “real man” has been molded by their unique histories, environments, and dominant religious beliefs, Gilmore found that almost all them share three common imperatives or moral injunctions — what I call the 3 P’s of Manhood: a male who aspires to be a man must protect, procreate, and provide.

Despite being an academic book, Manhood in the Making is a fairly easy and enjoyable read. I couldn’t put it down after I started it and several times could sense a veritable light bulb going off above my head.

Is There Anything Good About Men? How Cultures Flourish by Exploiting Men

In Is There Anything Good About Men?, eminent professor of psychology Roy F. Baumeister flips the feminist argument that it’s only women who have been oppressed and exploited from the beginning of time. Baumeister argues that, in many ways, men are the ones that society “exploits” (even if they accept their responsibilities willingly). He explores the fact that throughout history men have been seen as far more expendable than women; they’re the ones who went to war, took the dirty jobs, and sacrificed their lives to advance civilization.

That might seem like a controversial thesis to some, but Baumeister lays it out in a very sensible, straightforward, non-inflammatory, and ultimately hard-to-argue-with way. He uses studies from the growing fields of evolutionary psychology and sociobiology to explain why cultures have exploited men the way they have. And he explains how and why certain aspects of male and female behavior are hardwired and that these differences should be used to complement each other rather than as fodder in the gender wars.

The book is a really interesting read, but honestly, the article he wrote that became the book sums up his main points much more succinctly and for free!

Listen to my podcast interview with Dr. Roy R. Baumeister.

Men In Groups

You’ve probably heard the phrase “male bonding.” Well, this is the book where it originated from. In Men in Groups, anthropologist Lionel Tiger takes a look at the ingrained male propensity to form and act in gangs. Looking at primatology, sociobiology, and anthropology, Tiger highlights the fact that human males are very adept at forming male-only coalitions in order to dominate something — be it a competing tribe, a competing business, or even nature itself. He argues that this tendency for human males to organize in male-only coalitions is an evolved trait; similar male grouping patterns are seen in our closest primate relative, the chimpanzee. He goes on to describe how across cultures, males often bond with one another through competition amongst themselves and that this intra-group competition may be a way to prepare for inter-group competition with other teams/gangs.

Men in Groups was written in 1969 so a lot of the research in it is old and outdated. Even so, the main thesis of the book is still relevant today, and many modern sociologists and anthropologists have built on the initial work done by Tiger.

Also be sure to check out Tiger’s The Decline of Males for an interesting treatise on how the advent of birth control has impacted modern masculinity.

Listen to my podcast interview with Dr. Lionel Tiger.

Plato and the Hero: Courage, Manliness, and the Impersonal Good

The Professor in the Cage: Why Men Fight and Why We Like to Watch

Research shows that men are drawn to violence, be it the criminal or sporting kind. Why is that? In The Professor in the Cage, english professor Jonathan Gottschall takes us on a personal as well as interdisciplinary tour to answer that question.

Using his experience training to be an MMA fighter, as well as looking to research from biology, anthropology, and sociology, Gottschall argues that men are both made and conditioned to fight. We’ve got a fighting spirit inside of us that can be used for good or evil — simply depending on how this energy is directed. Gottschall does a great job tying together all the research about manhood and the male fighting instinct in an accessible, enlightening, and entertaining read. If you enjoyed our honor and manhood series, then you’ll certainly get a lot out of this book.

Listen to my podcast interview with Jonathan Gottschall.

The Poetics of Manhood: Contest and Identity in a Cretan Mountain Village

While many of the books on this list concentrate on broad, general examinations of masculinity, The Poetics of Manhood brings the discussion down to earth and into the specifics. During the 1960s, anthropologist Michael Herzfeld lived among the people inhabiting a small, mountainous village on the island of Crete, observing their culture of masculinity. The resulting field study Herzfeld wrote up isn’t always the clearest or easiest read, but the book is chockfull of interesting tidbits on the nature of lived manhood, with insights on why men are drawn to meat, risk, competition, and improvisation. This is the book where the idea of “being a good man vs. being good at being a man” originates, though the Cretans used it in a slightly different way than it’s come to be understood in the modern manosphere.

The Hunting Hypothesis

In The Hunting Hypothesis, playwright and paleoanthropologist Robert Ardrey eloquently lays out the case that hunting is what made humans, humans. Not only did the meat from hunting increase the brain size of our early human ancestors, but hunting acted as a selection method for traits that we consider uniquely human. Ardrey argues that speech, large group co-operation, abstract thinking, and tool making can all trace their roots back to hunting. What’s more, he argues that men in particular were selected for hunting due to their larger stature, strength, and propensity for risk taking. While Ardrey’s theory was originally controversial when first published in 1976, it’s now accepted by many anthropologists, evolutionary biologists, and psychologists.

What I love most about this book is how absolutely fun it is to read. Ardrey’s talent as a playwright and screenwriter shine through in his work and he’s able to take complex ideas like paleoanthropology and make them accessible to the layman.

Another Ardrey book to check out that’s tangentially related to The Hunting Hypothesis is The Territorial Imperative. In that book he takes a look at the human drive toward territoriality and the implications it has on property ownership and nation building. It doesn’t really get into the topic of gender differences or why men are the way they are like The Hunting Hypothesis does, but it’s still a fascinating and worthwhile read.

Heroes, Rogues, & Lovers: Testosterone and Behavior

We all know that testosterone is what makes men (generally) stronger and more aggressive than women, but how does this hormone affect other areas of a man’s life? In Heroes, Rogues, & Lovers: Testosterone and Behavior, cognitive psychologist James M. Dabbs (along with his wife Mary) highlight research showing testosterone’s effect on behavior in the workplace, in school, in the bedroom, and even in utero. This is one of the most fascinating and engaging books I’ve read. No other book out there tackles the topic of testosterone’s effect on human behavior like this one. If you want a more complete understanding of why men behave the way they do, pick up a copy.

Fighting for Life: Contest, Sexuality, and Consciousness

Walter J. Ong was a Jesuit priest who spent his career as an academic studying and writing about how humanity’s transition from an oral to written culture changed human consciousness. In Fighting for Life Ong takes a look at how competition — particularly male competition — has shaped human consciousness. He focuses on how the male drive for competition influenced philosophers and academics from ancient Greece through the Enlightenment to create a learning environment that was agonistic and competitive. Ong argues that after the Romantic Era, education became much more “feminized” and an emphasis on co-operation rather than competition began to pervade classrooms. Fighting for Life was originally published in 1981, but the insights Ong had have later been confirmed by researchers exploring how boys and girls learn differently. For example, check out Boys Adrift by Dr. Leonard Sax which highlights research showing that boys thrive academically when there’s an element of competition in the classroom.

Roman Honor: The Fire in the Bones

Back in 2012, we published a series on the history and decline of traditional manly honor in the West. I thought I had turned over every rock when researching those posts, but a few months after we wrapped up the series, I came across Roman Honor: The Fire in the Bones by Carlin Barton, a professor of ancient history at the University of Massachusetts. I wish I had known about this book when I was researching and writing my series on honor. Roman Honor is the best book I’ve read on honor — bar none. Barton masterfully explores how honor shaped the lives of ancient Rome from the early days of the Republic and all the way through the fall of the empire. She shows how small, intimate groups are vital for honor to survive and how imperialism kills it. This book is a hard read, but it’s well worth the effort. The insights are so brilliant they’re almost startling, and even the footnotes are packed with fascinating asides.

Listen to my podcast interview with Dr. Carlin Barton.

Manvotionals: Timeless Wisdom and Advice on Living the 7 Manly Virtues

I promise this isn’t a shameless plug (at least not entirely!); Manvotionals is an anthology of letters, speeches, quotes, etc., from history’s eminent men, so I can’t at all take credit for the wisdom contained therein! I can only say that putting together this collection really helped refine my vision and understanding of what I consider the 7 manly virtues: manliness (it’s a distinct virtue in and of itself), courage, industry, resolution, self-reliance, discipline, and honor (integrity). This is my favorite book we’ve ever put out, and I still return to it personally in order to revitalize my vision and aim for becoming the kind of man I want to be: one who maximizes his full potential in body, mind, and soul, effectively uses his abilities to fulfill his life’s purposes, and overcomes setbacks and challenges to make a difference and leave a real and lasting legacy.

Tags: book lists

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

De islam is daar een extreme exponent van, zie Boko Haram, maar ook het ‘blanke’, Europese vooruitgangsdenken van de pionier-ontdekkingsreiziger is mannelijk-imperialistisch. Neen, we huwen geen kindbruidjes (meer) uit, maar de onderliggende macho-cultuur is ook de onze. Poetin, Assad, maar ook Juncker of Verhofstadt of Michel, kampioenen van de democratie, zijn in hetzelfde bedje ziek: voluntaristische ego’s die’ willen ‘scoren’ en van erectie tot erectie evolueren. Altijd is er een doel, een schietschijf, een trofee.

De islam is daar een extreme exponent van, zie Boko Haram, maar ook het ‘blanke’, Europese vooruitgangsdenken van de pionier-ontdekkingsreiziger is mannelijk-imperialistisch. Neen, we huwen geen kindbruidjes (meer) uit, maar de onderliggende macho-cultuur is ook de onze. Poetin, Assad, maar ook Juncker of Verhofstadt of Michel, kampioenen van de democratie, zijn in hetzelfde bedje ziek: voluntaristische ego’s die’ willen ‘scoren’ en van erectie tot erectie evolueren. Altijd is er een doel, een schietschijf, een trofee.

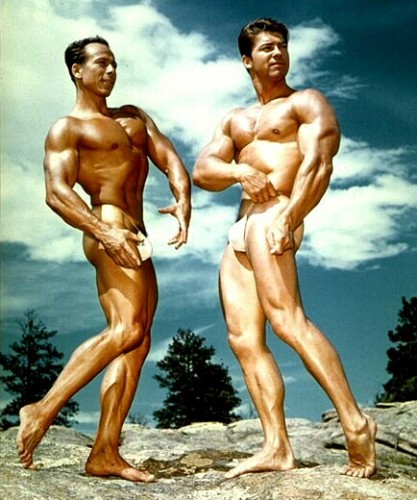

Men of the 19th and early 20th centuries also saw manliness not simply as a collection of different virtues, but as a virtue in and of itself – a distinct quality. They encouraged men to embrace manliness as the crown of character – as a kind of ineffable bonus power that was produced when all the other virtues were combined (the Captain Planet of the virtues, if you will). Manliness was often noted as a separate, preeminent trait in men worthy of admiration:

Men of the 19th and early 20th centuries also saw manliness not simply as a collection of different virtues, but as a virtue in and of itself – a distinct quality. They encouraged men to embrace manliness as the crown of character – as a kind of ineffable bonus power that was produced when all the other virtues were combined (the Captain Planet of the virtues, if you will). Manliness was often noted as a separate, preeminent trait in men worthy of admiration:

One of the most poignant tales of a famous man admitting to being unmanned comes from Abraham Lincoln. One of the first deaths in the Civil War – Elmer Ellsworth — was a close friend of the president. Right after receiving news of Ellsworth’s death, a reporter and Senator came into the White House library to speak with Lincoln. Upon entering, they saw him gazing mournfully out the window at the Potomac. He abruptly turned around, stuck out his arm, and said, “Excuse me, but I cannot talk.” He then burst into tears and began walking around the room, holding a handkerchief to his face as he cried. The two visitors were unsure of what to do; as the reporter later remembered, they were “moved at such an unusual spectacle, in such a man, in such a place.” After several minutes, the president turned to them and said, “I make no apology gentlemen, for my weakness, but I knew poor Ellsworth well, and held him in high regard. Just as you entered the room, Captain Fox left me, after giving me the painful details of his unfortunate death. The event was so unexpected, and the recital so touching, that it quite unmanned me.” Lincoln then “made a violent attempt to restrain his emotion” before sharing the details of his friend’s death.

One of the most poignant tales of a famous man admitting to being unmanned comes from Abraham Lincoln. One of the first deaths in the Civil War – Elmer Ellsworth — was a close friend of the president. Right after receiving news of Ellsworth’s death, a reporter and Senator came into the White House library to speak with Lincoln. Upon entering, they saw him gazing mournfully out the window at the Potomac. He abruptly turned around, stuck out his arm, and said, “Excuse me, but I cannot talk.” He then burst into tears and began walking around the room, holding a handkerchief to his face as he cried. The two visitors were unsure of what to do; as the reporter later remembered, they were “moved at such an unusual spectacle, in such a man, in such a place.” After several minutes, the president turned to them and said, “I make no apology gentlemen, for my weakness, but I knew poor Ellsworth well, and held him in high regard. Just as you entered the room, Captain Fox left me, after giving me the painful details of his unfortunate death. The event was so unexpected, and the recital so touching, that it quite unmanned me.” Lincoln then “made a violent attempt to restrain his emotion” before sharing the details of his friend’s death.

Die verhängnisvolle Entwicklung der Männerverachtung findet für den Vertreter des männlichen Geschlechts ihren frühen Anfang heutzutage schon in Kindergarten und Schule: Ein Blick auf das derzeitige Schulsystem allein genügt, um festzustellen: Hier werden haufenweise Verlierer produziert, die Mehrheit ist männlich.

Die verhängnisvolle Entwicklung der Männerverachtung findet für den Vertreter des männlichen Geschlechts ihren frühen Anfang heutzutage schon in Kindergarten und Schule: Ein Blick auf das derzeitige Schulsystem allein genügt, um festzustellen: Hier werden haufenweise Verlierer produziert, die Mehrheit ist männlich. Ein Jahrhundert danach kann man sich nur wundern, dass die Zensur Thomas Manns zweiten Roman, "Königliche Hoheit", nicht sofort verboten hat. Der Erbprinz des kleinen Großherzogtums, wo der Roman aus dem Jahr 1909 spielt, kommt mit einer verkümmerten linken Hand zur Welt. Es ist genau dieselbe Behinderung, mit der auch Kaiser Wilhelm II. geboren war, der Berliner Hof gab sich seit Jahrzehnten alle erdenkliche Mühe, diese Schwäche zu kaschieren, auf offiziellen Bildern ist die linke Seite in Halbdunkel belassen.

Ein Jahrhundert danach kann man sich nur wundern, dass die Zensur Thomas Manns zweiten Roman, "Königliche Hoheit", nicht sofort verboten hat. Der Erbprinz des kleinen Großherzogtums, wo der Roman aus dem Jahr 1909 spielt, kommt mit einer verkümmerten linken Hand zur Welt. Es ist genau dieselbe Behinderung, mit der auch Kaiser Wilhelm II. geboren war, der Berliner Hof gab sich seit Jahrzehnten alle erdenkliche Mühe, diese Schwäche zu kaschieren, auf offiziellen Bildern ist die linke Seite in Halbdunkel belassen.

Brett and Kate McKay

The Art of Manliness: Classic Skills and Manners for the Modern Man

Cincinnati: How Books, 2009

It’s hard not to like this book. However, it’s really the idea of the book that I like, rather than the book itself. In fact, I almost hesitate to write this review (which will not be wholly positive) because I think the authors have their hearts in the right place, and because I like their website http://artofmanliness.com/

When I showed this book to a young friend of mine he was incredulous: “Do we really need a manual on being a man?” he asked. Well, yes it appears we do. As the authors say in their introduction “something happened in the last fifty years to cause . . . positive manly virtues and skills to disappear from the current generations of men.” They don’t really tell us what they think that something is, but two paragraphs later they remark: “Many people have argued that we need to reinvent what manliness means in the twenty-first century. Usually this means stripping manliness of its masculinity and replacing it with more sensitive feminine qualities. We argue that masculinity doesn’t need to be reinvented.”

I wanted to let out a cheer at this point, but I was sitting in the American Film Academy Café in Greenwich Village, surrounded by young white male geldings and their Asian girlfriends. So I kept my mouth shut and noted to myself that the McKays are clearly not PC, though there are minor nods to political correctness here are there. One gets the feeling that they know more than they are letting on in this book. And one gets the feeling they are employing a simple and sound strategy: to seduce male readers with the natural appeal of traditional manliness – while revealing just-so-much of their political incorrectness so as not to completely alienate their over-socialized readers.

Still, the McKays are pretty socialized themselves, and one sees this immediately on opening the book and finding that it is dedicated to two members of “the greatest generation.” Ugh. Yes, I do think there’s much to admire about my grandfather’s generation, but I long ago came to detest the conventional-minded romanticism about America’s great crusade in WWII. And the very use of the phrase “greatest generation” has become a cliché.

However, the real trouble begins after the introduction, when one finds that the first section of the book is devoted to how to get fitted for a suit. Then we are instructed in how to tie a tie. For some unaccountable reason the tying of the Windsor knot is included here. (Like Ian Fleming, I have always regarded the Windsor knot as a mark of a vain and unserious man.) This is followed by sections on how to select a hat, how to iron a shirt, how to shave, and how not to be a slob at the dinner table. So far so good: I know all this stuff, so I guess I’m pretty manly. Of course, the problem here is that this is all in the realm of appearance. To be fair, the McKays do go on to include much in their book about character, but one must wade through a lot of inessential stuff to get there.

At one point we are instructed in how to deliver a baby. The McKays’ core piece of advice here is “get professional help!” Curiously, this is also the central tenet of their brief lectures on dealing with a snakebite and landing a plane. The baby having been delivered, the reader will find further instructions on how to change a diaper and how to braid your daughter’s hair. (This is what happens when you co-author a book with your wife.) The McKays’ advice on raising children is sound. They advise us not to try and be our child’s best friend.

Once you have tended to your daughter’s snakebite and braided her hair (in that order, please), you can turn to manlier things like how to win a fight, how to break down a door, how to change a flat tire, how to jump start a car, how to go camping, how to navigate by the stars, and how to tie knots. Then it will be Miller time, and you will want some manly friends to hang out with.

The section on male friendship, in fact, is one of the best parts of the book. The McKays remind us that in ancient times “men viewed male friendship as the most fulfilling relationship a person [i.e., a man] could have.” They attribute this, however, to the fact that men saw women as inferior. This is at best a half-truth. The real reason men saw male friendship as more fulfilling than relations with women is because it is. There are vast differences between men and women, and while they may be able to have close, loving relationships they never really understand each other, and their values clash.

Women are primarily concerned with the perpetuation of the species. They are the peacemakers, who just want us all to get along, because their main concern is what Bill Clinton called “the children.” By contrast, men find their greatest fulfillment in achieving something outside the home: they are only fully alive when they are fighting for some kind of value. A man can only be truly understood by another man.

Thus was born what the McKays refer to as “the heroic friendship”: “The heroic friendship was a friendship between two men that was intense on an emotional and intellectual level. Heroic friends felt bound to protect one another from danger.” The McKays devote some discussion to the decline of close male friendships, and they have a lot to say about the disappearance of affection among male friends.

A while back I found myself in a bookstore flipping through a book of photographs from WWII. Many of them depicted soldiers, sailors, and marines relaxing or goofing around. What was remarkable about many of these pictures was the affection the men displayed for one another. There was one photo, for example, of a sailor asleep with his head in another sailor’s lap. This is the sort of thing that would be impossible today, because of fear of being thought “gay.” The McKays mention this problem. As George Will once said, the love that dare not speak its name just can’t seem to shut up lately. And it has ruined male bonding. Thus was born the “man hug” with the three slaps on the back that say I’M (THUMP) NOT (THUMP) GAY (THUMP). (Yes, the McKays instruct us on how to perform the man hug in both its American and international versions.)

Another thing that has ruined male friendships is women, but in a number of different ways. First of all, as every man knows, women have now invaded countless previously all-male areas in life. This usually results in ruining them for men. Second, many women resent it when their husbands or partners want to spend time with their male friends. In earlier times, men would spend a significant amount of time away from their wives working or playing with male peers. But no longer. Now women expect to be their husband’s “best friend,” and men today passively go along with this. The result is that they often become completely isolated from their male friends. It is quite common today, in fact, for men to expect that marriage means the end of their friendship with another man. Please note that all of the above problems have only been made possible by the cooperation of men – by their not being manly enough to say “no” to women.

Eventually, one finds the McKays dealing with matters having to do with manly character, such as their discussion of the characteristics of good leadership. A lot of what they have to say is sound advice, but it is not without its problems. At one point they invoke old Ben Franklin and his homey list of virtues. Anyone interested in this topic should read D. H. Lawrence’s hilarious demolition of Franklin in Studies in Classic American Literature. Franklin is the archetypal American, extolling (among other things) temperance, frugality, industry, and cleanliness. This is setting our sights very low, and it’s not the least bit manly. If I’m going to take lessons in manliness from an American I’d much rather get them from Charles Manson.

There are other problems I could go on about, such as the McKays advising us to give up porn because it “objectifies women” (“But that’s the whole point!” a friend of mine responded when I told him this). However, as I said earlier, their heart is in the right place. Whatever its flaws, this book is a celebration of traditional manhood and an honest, well-intentioned attempt to improve men.

Still, there is something undeniably creepy and postmodern about this book. If you follow all of its instructions you won’t be a traditional manly man, you’ll be an incredible, life-like simulation of one. The reason is that everything they talk about came naturally to our forebears. It flowed from their characters, and their characters flowed from their life experience. But their life experience was quite different from ours. They were not constantly shielded from danger and from risk taking. They had myriad ways open to them to express and refine their manly spirit. They had manly rites of passage. Their spirits were not crushed by decades of PC propagandizing. They had been tested by wars, famines, depressions. They were tough sons of bitches, and nobody needed to tell them how to win a fight. And if you tried to tell them how to braid their daughters’ hair you’d better be ready for a fight.

True manliness is not the result of acquiring the sort of “how to” knowledge the McKays try to provide us with. Manliness is not an art, not a techne – but it’s inevitable that we moderns, even good moderns like the McKays, would think that it is. Manliness is a way of being forged through trials and tribulations. In a world without trials and tribulations, in the “safe” and “nice” modern, industrial, liberal, democratic world it’s not at all clear that true manliness is possible anymore. Except, perhaps, through rejecting that world. The subtext to The Art of Manliness is anti-modern. But the achievement (or resurrection) of manliness has to raise that anti-modernism out from between the lines and make it the central point.

At its root, modernity is the suppression of manly virtues and manly values. This is the key to understanding the nature of the modern world and our dissatisfaction with it. Manliness today can only be truly asserted through revolt against all the forces arrayed against manliness – through revolt against the modern world .

.