Kay S. Hymowitz

Manning Up: How the Rise of Women Has Turned Men into Boys

New York: Basic Books, 2011

I expected this book to be a diatribe against the often-discussed “loser” men—those who, not having any marketable skill, are still living off their parents into mid-life. Manning Up actually is about a new demographic, the SYM (single young male), its female counterpart, and what factors led to the decline in marriage and number of children in the Western world. Simply having a job is not enough to be a man in the author’s view; true adulthood means being married and having children. Most young men and women are what she calls “preadults.”

Kay S. Hymowitz, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, has written extensively on issues of marriage, the sexes, class, and race, and she appears to be genuinely concerned about the declining rates in marriage childbirth. Her stance is slanted in favor of women, but she is sympathetic to the plight of men today. She mentions that boys are often discriminated against and ignored in favor of women. While funds pour in to increase girls’ math and science scores, boys are not given special treatment to improve their reading scores. She cites a BusinessWeek story that explains today’s young men as a “payback generation” intended to “compensate for the advantages given to males in the past.”

The Shift to the Feminine, Knowledge Economy

Scholars attribute women’s entry into the workforce largely to innovations in science and technology in the twentieth century. With no need to can food, make bread, weave, or sew, women were not “needed” at home the way they were in every generation past. They were having fewer children, too, due to birth control: In the early 1800s, white women had an average of seven children. By 1900, it was 3.56. When the birth control pill was introduced in the 1960s, state laws “kept the drug away from unmarried women.” Economist Martha Baily showed that when a state changed its law, there was a decline in the percentage of young women who gave birth by age 22, and an increase in the number of young women in the labor force and the hours they worked.

The number of working women (ages 33 to 45) went from 25 percent in 1950, to 46 percent in 1970, to about 60 percent since 1995. But in the 1950s to ’70s, women tended to work to help pay the bills, often as secretaries, waitresses, nurses, teachers, and librarians. Today’s young women set out in the world to find their “passion” not in a husband, but in a career.

The shift from secretary to major player in corporate America, Hymowitz explains, was largely due to a shift from an industrial economy to a knowledge economy. By the 1980s, the economy was booming as manufacturing jobs decreased and millions of positions opened in fields like public relations, health, and law. Women, too weak physically to participate much in the industrial economy, could do almost any job in the knowledge economy.

One example given is design. As technology advanced, designers transitioned from working with their hands (and making lasting work as is found in Bauhaus and Art Nouveau) to being hands-off fashion designers, who no longer needed to learn drafting, typesetting, drawing, or how to use heavy equipment. Using cheap labor overseas meant many more products, and thus a greater need for marketing and advertising. Women now make up 60 percent of design students, once a male-dominated field.

New industries sprouted up, too, as increased wealth and leisure time demanded workers at yoga centers, spas, travel companies, and more marketing and ad agencies for these specialty industries—all areas in which women participate as easily as men. Working women had new needs and money to spend, so more industries sprouted up to create feminine business suits, trendy lunch spots, meal “helpers,” stylish computer bags, $400 work pumps, $5 lattes, spa treatments and scented candles to help women unwind, houses with bathrooms the size of our grandparents’ bedrooms, a variety of products in the color pink, and right-hand rings for women who want to buy themselves a diamond. Other women entered the design arena through boutique companies: making jewelry, crafts, or custom stationary.

Nation-building and culture-building thus fell out of the workforce, replaced by sales, marketing, and fashion.

Today, men outnumber women in fields like construction (88 percent), while women make up 51 percent of management and professionals, particularly in fields like Human Resources, Public Relations, and finance. Women make up 77 percent of workers in education and health services. Women are more likely to work at the numerous new nonprofits, and make up 78 percent of psychology majors, 61 percent of humanities majors, and 60 percent of social and behavioral science doctorates. Publishing has long had high numbers of women workers, but now women have moved from what Hymowitz calls the “ladies’ magazines ghettos” to political commentary.

While women moved into the knowledge economy, men remained in behind-the-scenes fields that required more technical skill: jobs like writing code and IT. Some men flocked to jobs at ESPN, Cartoon Network, microbreweries, and video game design firms. Other men knew that even in the midst of feminism, their wives would still want the option to stay home and raise children (so long as men didn’t tell them they had to), and concentrated on high-paying jobs rather than following their bliss.

In the early nineteenth century, most men worked for themselves, as farmers, small merchants, or tradesmen. But by the end of the nineteenth century, two-thirds were working for “the man.” Some experts believe that it’s women who will soon be “running the place,” since the knowledge economy workplace “requires a more feminine style of leadership.” Employers will increasingly placate women, who are not solely concerned with the bottom line as a measure of their career success, but also want a job where they “help others,” enjoy relationships with colleagues, get recognition, have flexibility, and are in an environment of “collaboration and teamwork.” More women in the workplace means that it is more genteel and less of a man’s club: Swearing and spitting are forbidden, and men are now in a domesticated atmosphere both at home and at work. The popularity of psychoanalysis means that men and women alike are trained to listen sympathetically, be sensitive to emotions, and control their anger.

To explain the dynamics of the knowledge economy, Hymowitz references a 2002 paper by Harvard economist Brian Jacob called “Where the Boys Aren’t.” He found that girls are better at noncognitive tasks, such as keeping track of homework, working well with others, and organization, and suggests that such skills may explain the gender gap in high school grades and college admissions (women have higher GPAs and are 58 percent of college graduates, but they lag behind men in math SAT scores). These cognitive skills also are important for success in today’s feminized workplace.

Though not mentioned in Manning Up, these skills are also ones for which men have traditionally relied on women: organizing the home, keeping track of appointments, and being the family PR rep and social coordinator. Today’s women benefit in the career-world, as more jobs require good communication skills and “EQ” (emotional intelligence), while men are left with lower paying jobs and the added disadvantage of no wife at home.

SYMs: The New Demographic

In 1970, 80 percent of men aged 25–29 were married, compared to 40 percent in 2007. In 1970, 85 percent of men aged 30–34 were married, compared to 60 percent in 2007.

This new single-young-male demographic used to be called “elusive,” since it was a difficult advertising target. Then Maxim arrived in America in 1997, and seemed to have the answers to what SYMs wanted. Its readership reached 2.5 million in 2009, more than the combined circulation of GQ, Men’s Journal, and Esquire. Hymowitz says other magazines, like Playboy and Esquire, tried to project the “image of an intelligent, cultured, and au courant sort of man.” Even though Playboy promoted the image of the eternal bachelor, he was at least an intelligent and sophisticated bachelor. (Hugh Hefner wrote that his readers enjoyed “inviting a female acquaintance in for a quiet discussion of Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, sex.”) Maxim, however, catered to the man who didn’t want to grow up.

Hymowitz doesn’t buy into the idea that the masses of men are moved by the media (or an inner party seeking to destroy them, let alone any subversive forces dominant in the Kali Yuga). She instead posits that products like Maxim were developed for an existing market.

Regardless of the reason, a number of TV shows were created with the SYM in mind, starting with The Simpsons. Comedy Central brought out South Park and The Man Show, while the Cartoon Network promoted cartoons for grown men. More films featured SYM stars like Will Ferrell, Ben Stiller, Jim Carrey, and Jack Black, and movies like 2003’s Old School (30-somethings who start a fraternity) were popular. American men ages 18–34 are now the biggest users of video games, with 48.2 percent owning a console and playing an average of 2 hours and 43 minutes per day. That doesn’t include online games like World of Warcraft.

Hymowitz recounts the numerous silly Adam Sandler movies, in which he plays a stereotypical young adult, male loser. Meanwhile, the media’s counter-image for women is the well-heeled, single young female:

If she is ambitious, he is a slacker. If she is hyper-organized and self-directed, he tends toward passivity and vagueness. If she is preternaturally mature, he is happily not. Their opposition is stylistic as well: she drinks sophisticated cocktails in mirrored bars, he burps up beer on ratty sofas. She spends her hard-earned money on mani-pedi outings, his goes toward World of Warcraft and gadgets.

It’s in this chapter that Hymowitz’s double-standard for men and women is most apparent, and annoying. She seems to think that when single women spend money for clothes and pedicures, it’s women’s empowerment, but single men who spend money on guy-flicks and video games are childish. Both cases seem to me examples of adults who, instead of having children, make themselves into the child: men by continuing all the games and comic books of their youth, and women by playing Barbie doll with themselves.

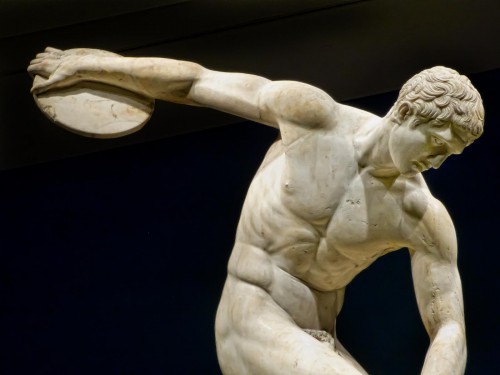

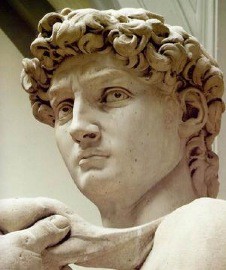

So if simply cutting the financial apron strings doesn’t make one a man, what does? Hymowitz answers by looking to masculine virtues throughout all cultures: “strength, courage, resolve, and sexual potency,” but that one line is about the extent of the analysis. She is careful to distinguish between having sex (which single men do a lot these days) and “manning up” by being married and becoming the head of a family.

But even when men do settle down, the roles they play as fathers have changed. Rather than being a strong father figure, today’s father often relates to his children by “accentuating his own immaturity,” according to Gary Cross, author of Men to Boys: The Making of Modern Immaturity. Whether they want to or not, middle-class men are often “expected to bring home a spirit of playfulness that would have scandalized their own patriarchal fathers.” The middle-class home has became more child-centric, even with fewer children in it, and both sexes are expected to project “warmth, nurturing, and gentleness.”

With high divorce rates, many young men today were raised in matriarchal family environments, which may be one contributing factor to the “unmanliness” of some of today’s men. Instead of having their own families, some men instead play the role of the “fun uncle,” like men in matriarchal, non-white societies.

A Different Dating World

After college, all of these single young people embark on a journey more confusing than if they started a family: modern dating, now with websites that describe the etiquette for one-night stands (it’s “leave quickly”).

Men and women are both confused by the new rituals, and the lack thereof. A man who inadvertently insults a girl by not opening her car door may have been chastised by his last girlfriend for doing just that. Women sometimes “pick up” guys (whether at bars, or actually driving to pick them up for dates), and there is ambiguity about who pays for dates when SYFs outearn SYMs in the majority of large cities. Men experience the nice-guy conundrum when they see girls dating jerks. Meanwhile, women practice a Zen-like nonattachment when dating, since bringing up marriage before a year of sex seems to turn men off.

Hymowitz recounts a number of events from the childhood of young women that play into their behavior as adults: Today’s SYFs were often told by their mothers that they shouldn’t need a man to be happy. They were likely raised in the 1990s, in the midst of a tween-based advertising frenzy that marketed make-up, thong underwear, and high-heeled clogs to preteens, while at the same time trying to “save the self-esteem” of young girls. Popular TV shows for girls were based on the female warrior type: The Powerpuff Girls, Xena: Warrior Princess, and Buffy the Vampire Slayer. These women try to convince themselves for years that they shouldn’t “need” a child or husband, then end up debating whether to become a “choice mother” (the new term for a woman who uses sperm bank).

* * *

Manning Up might be a good “beach book” for women readers of Counter-Currents, but I have trouble imagining men enjoying it, though they would find some insights into the mind of the typical woman. I found it interesting for its wealth of statistics about marriage rates and ages, men and women in the workplace and universities, and summaries of various causes that contributed to the (mostly white) single and childless young men and women today.

There have been numerous debates on Counter-Currents and other websites about what exactly has caused the decline in marriage and childbirth. Manning Up does a good job of touching on some of the contributing forces, but never addresses any of the larger forces.

The good news from Manning Up is that the majority of young men and women still want to get married and have children. In addition, while women in their early 20s are “hot commodities,” by the time they reach 30, they are beginning to get desperate and may “settle for Mr. Good Enough” as the subtitle of the book Marry Him advises. More good news lies in the fact that young people today are scrambling for any advice whatsoever about how to successfully date and marry, revealing a large market for New Righters and Traditionalists to step into to help young people successfully navigate through the increasingly unsatisfying modern world.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Men of the 19th and early 20th centuries also saw manliness not simply as a collection of different virtues, but as a virtue in and of itself – a distinct quality. They encouraged men to embrace manliness as the crown of character – as a kind of ineffable bonus power that was produced when all the other virtues were combined (the Captain Planet of the virtues, if you will). Manliness was often noted as a separate, preeminent trait in men worthy of admiration:

Men of the 19th and early 20th centuries also saw manliness not simply as a collection of different virtues, but as a virtue in and of itself – a distinct quality. They encouraged men to embrace manliness as the crown of character – as a kind of ineffable bonus power that was produced when all the other virtues were combined (the Captain Planet of the virtues, if you will). Manliness was often noted as a separate, preeminent trait in men worthy of admiration:

One of the most poignant tales of a famous man admitting to being unmanned comes from Abraham Lincoln. One of the first deaths in the Civil War – Elmer Ellsworth — was a close friend of the president. Right after receiving news of Ellsworth’s death, a reporter and Senator came into the White House library to speak with Lincoln. Upon entering, they saw him gazing mournfully out the window at the Potomac. He abruptly turned around, stuck out his arm, and said, “Excuse me, but I cannot talk.” He then burst into tears and began walking around the room, holding a handkerchief to his face as he cried. The two visitors were unsure of what to do; as the reporter later remembered, they were “moved at such an unusual spectacle, in such a man, in such a place.” After several minutes, the president turned to them and said, “I make no apology gentlemen, for my weakness, but I knew poor Ellsworth well, and held him in high regard. Just as you entered the room, Captain Fox left me, after giving me the painful details of his unfortunate death. The event was so unexpected, and the recital so touching, that it quite unmanned me.” Lincoln then “made a violent attempt to restrain his emotion” before sharing the details of his friend’s death.

One of the most poignant tales of a famous man admitting to being unmanned comes from Abraham Lincoln. One of the first deaths in the Civil War – Elmer Ellsworth — was a close friend of the president. Right after receiving news of Ellsworth’s death, a reporter and Senator came into the White House library to speak with Lincoln. Upon entering, they saw him gazing mournfully out the window at the Potomac. He abruptly turned around, stuck out his arm, and said, “Excuse me, but I cannot talk.” He then burst into tears and began walking around the room, holding a handkerchief to his face as he cried. The two visitors were unsure of what to do; as the reporter later remembered, they were “moved at such an unusual spectacle, in such a man, in such a place.” After several minutes, the president turned to them and said, “I make no apology gentlemen, for my weakness, but I knew poor Ellsworth well, and held him in high regard. Just as you entered the room, Captain Fox left me, after giving me the painful details of his unfortunate death. The event was so unexpected, and the recital so touching, that it quite unmanned me.” Lincoln then “made a violent attempt to restrain his emotion” before sharing the details of his friend’s death.

Die verhängnisvolle Entwicklung der Männerverachtung findet für den Vertreter des männlichen Geschlechts ihren frühen Anfang heutzutage schon in Kindergarten und Schule: Ein Blick auf das derzeitige Schulsystem allein genügt, um festzustellen: Hier werden haufenweise Verlierer produziert, die Mehrheit ist männlich.

Die verhängnisvolle Entwicklung der Männerverachtung findet für den Vertreter des männlichen Geschlechts ihren frühen Anfang heutzutage schon in Kindergarten und Schule: Ein Blick auf das derzeitige Schulsystem allein genügt, um festzustellen: Hier werden haufenweise Verlierer produziert, die Mehrheit ist männlich.

Brett and Kate McKay

The Art of Manliness: Classic Skills and Manners for the Modern Man

Cincinnati: How Books, 2009

It’s hard not to like this book. However, it’s really the idea of the book that I like, rather than the book itself. In fact, I almost hesitate to write this review (which will not be wholly positive) because I think the authors have their hearts in the right place, and because I like their website http://artofmanliness.com/

When I showed this book to a young friend of mine he was incredulous: “Do we really need a manual on being a man?” he asked. Well, yes it appears we do. As the authors say in their introduction “something happened in the last fifty years to cause . . . positive manly virtues and skills to disappear from the current generations of men.” They don’t really tell us what they think that something is, but two paragraphs later they remark: “Many people have argued that we need to reinvent what manliness means in the twenty-first century. Usually this means stripping manliness of its masculinity and replacing it with more sensitive feminine qualities. We argue that masculinity doesn’t need to be reinvented.”

I wanted to let out a cheer at this point, but I was sitting in the American Film Academy Café in Greenwich Village, surrounded by young white male geldings and their Asian girlfriends. So I kept my mouth shut and noted to myself that the McKays are clearly not PC, though there are minor nods to political correctness here are there. One gets the feeling that they know more than they are letting on in this book. And one gets the feeling they are employing a simple and sound strategy: to seduce male readers with the natural appeal of traditional manliness – while revealing just-so-much of their political incorrectness so as not to completely alienate their over-socialized readers.

Still, the McKays are pretty socialized themselves, and one sees this immediately on opening the book and finding that it is dedicated to two members of “the greatest generation.” Ugh. Yes, I do think there’s much to admire about my grandfather’s generation, but I long ago came to detest the conventional-minded romanticism about America’s great crusade in WWII. And the very use of the phrase “greatest generation” has become a cliché.

However, the real trouble begins after the introduction, when one finds that the first section of the book is devoted to how to get fitted for a suit. Then we are instructed in how to tie a tie. For some unaccountable reason the tying of the Windsor knot is included here. (Like Ian Fleming, I have always regarded the Windsor knot as a mark of a vain and unserious man.) This is followed by sections on how to select a hat, how to iron a shirt, how to shave, and how not to be a slob at the dinner table. So far so good: I know all this stuff, so I guess I’m pretty manly. Of course, the problem here is that this is all in the realm of appearance. To be fair, the McKays do go on to include much in their book about character, but one must wade through a lot of inessential stuff to get there.

At one point we are instructed in how to deliver a baby. The McKays’ core piece of advice here is “get professional help!” Curiously, this is also the central tenet of their brief lectures on dealing with a snakebite and landing a plane. The baby having been delivered, the reader will find further instructions on how to change a diaper and how to braid your daughter’s hair. (This is what happens when you co-author a book with your wife.) The McKays’ advice on raising children is sound. They advise us not to try and be our child’s best friend.

Once you have tended to your daughter’s snakebite and braided her hair (in that order, please), you can turn to manlier things like how to win a fight, how to break down a door, how to change a flat tire, how to jump start a car, how to go camping, how to navigate by the stars, and how to tie knots. Then it will be Miller time, and you will want some manly friends to hang out with.

The section on male friendship, in fact, is one of the best parts of the book. The McKays remind us that in ancient times “men viewed male friendship as the most fulfilling relationship a person [i.e., a man] could have.” They attribute this, however, to the fact that men saw women as inferior. This is at best a half-truth. The real reason men saw male friendship as more fulfilling than relations with women is because it is. There are vast differences between men and women, and while they may be able to have close, loving relationships they never really understand each other, and their values clash.

Women are primarily concerned with the perpetuation of the species. They are the peacemakers, who just want us all to get along, because their main concern is what Bill Clinton called “the children.” By contrast, men find their greatest fulfillment in achieving something outside the home: they are only fully alive when they are fighting for some kind of value. A man can only be truly understood by another man.

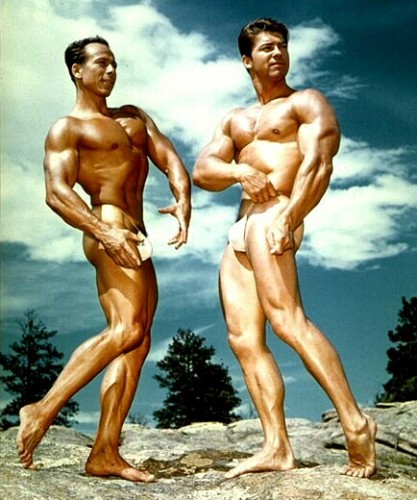

Thus was born what the McKays refer to as “the heroic friendship”: “The heroic friendship was a friendship between two men that was intense on an emotional and intellectual level. Heroic friends felt bound to protect one another from danger.” The McKays devote some discussion to the decline of close male friendships, and they have a lot to say about the disappearance of affection among male friends.

A while back I found myself in a bookstore flipping through a book of photographs from WWII. Many of them depicted soldiers, sailors, and marines relaxing or goofing around. What was remarkable about many of these pictures was the affection the men displayed for one another. There was one photo, for example, of a sailor asleep with his head in another sailor’s lap. This is the sort of thing that would be impossible today, because of fear of being thought “gay.” The McKays mention this problem. As George Will once said, the love that dare not speak its name just can’t seem to shut up lately. And it has ruined male bonding. Thus was born the “man hug” with the three slaps on the back that say I’M (THUMP) NOT (THUMP) GAY (THUMP). (Yes, the McKays instruct us on how to perform the man hug in both its American and international versions.)

Another thing that has ruined male friendships is women, but in a number of different ways. First of all, as every man knows, women have now invaded countless previously all-male areas in life. This usually results in ruining them for men. Second, many women resent it when their husbands or partners want to spend time with their male friends. In earlier times, men would spend a significant amount of time away from their wives working or playing with male peers. But no longer. Now women expect to be their husband’s “best friend,” and men today passively go along with this. The result is that they often become completely isolated from their male friends. It is quite common today, in fact, for men to expect that marriage means the end of their friendship with another man. Please note that all of the above problems have only been made possible by the cooperation of men – by their not being manly enough to say “no” to women.

Eventually, one finds the McKays dealing with matters having to do with manly character, such as their discussion of the characteristics of good leadership. A lot of what they have to say is sound advice, but it is not without its problems. At one point they invoke old Ben Franklin and his homey list of virtues. Anyone interested in this topic should read D. H. Lawrence’s hilarious demolition of Franklin in Studies in Classic American Literature. Franklin is the archetypal American, extolling (among other things) temperance, frugality, industry, and cleanliness. This is setting our sights very low, and it’s not the least bit manly. If I’m going to take lessons in manliness from an American I’d much rather get them from Charles Manson.

There are other problems I could go on about, such as the McKays advising us to give up porn because it “objectifies women” (“But that’s the whole point!” a friend of mine responded when I told him this). However, as I said earlier, their heart is in the right place. Whatever its flaws, this book is a celebration of traditional manhood and an honest, well-intentioned attempt to improve men.

Still, there is something undeniably creepy and postmodern about this book. If you follow all of its instructions you won’t be a traditional manly man, you’ll be an incredible, life-like simulation of one. The reason is that everything they talk about came naturally to our forebears. It flowed from their characters, and their characters flowed from their life experience. But their life experience was quite different from ours. They were not constantly shielded from danger and from risk taking. They had myriad ways open to them to express and refine their manly spirit. They had manly rites of passage. Their spirits were not crushed by decades of PC propagandizing. They had been tested by wars, famines, depressions. They were tough sons of bitches, and nobody needed to tell them how to win a fight. And if you tried to tell them how to braid their daughters’ hair you’d better be ready for a fight.

True manliness is not the result of acquiring the sort of “how to” knowledge the McKays try to provide us with. Manliness is not an art, not a techne – but it’s inevitable that we moderns, even good moderns like the McKays, would think that it is. Manliness is a way of being forged through trials and tribulations. In a world without trials and tribulations, in the “safe” and “nice” modern, industrial, liberal, democratic world it’s not at all clear that true manliness is possible anymore. Except, perhaps, through rejecting that world. The subtext to The Art of Manliness is anti-modern. But the achievement (or resurrection) of manliness has to raise that anti-modernism out from between the lines and make it the central point.

At its root, modernity is the suppression of manly virtues and manly values. This is the key to understanding the nature of the modern world and our dissatisfaction with it. Manliness today can only be truly asserted through revolt against all the forces arrayed against manliness – through revolt against the modern world .

.