Ancient philosophy, as Pierre Hadot has argued, was not merely a set of ideas but meant to include something far more practical: the leading of a good life in the pursuit of truth. In the case of Stoicism, as with Cynicism, the notion of leading a philosophical way of life is particularly explicit and central.[1] [2]

The philosopher is interested in living a life according to purpose and principle, as opposed to the frivolous or the popular. This necessarily can make him seem a bit of a kill-joy and can make interacting with what we call “normies” problematic. This is not a new problem. Here is Epictetus’ advice on avoiding gossip, chit-chat about the ball-game, and other small talk:

Lay down from this moment a certain character and pattern of behavior for yourself, which you are to preserve both when you’re alone and when you’re with others.

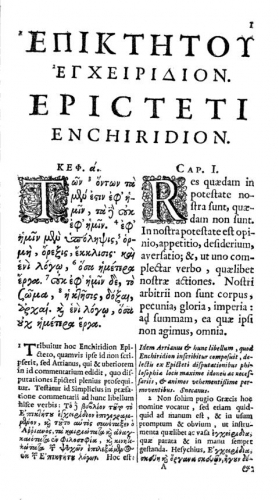

Remain silent for the most part, or say only what is essential, and in few words. Very infrequently, however, when the occasion demands, do speak, but not about any of the usual topics, not about gladiators, not about horse-races, not about athletes, not about food and drink, the subjects of everyday talk; but above all, don’t talk abut people, either to praise or criticize them, or to compare them. If you’re able to so, then, through the manner of your own conversation bring that of your companions round to what is fit and proper. But if you happen to find yourself alone among strangers, keep silent. (Handbook, 33)

“Show, don’t tell,” besides being good writing advice, is then an important Stoic principle concerning philosophy. One will always be tempted to make a philosophical and political point in order to show off or best another in argument, which of course defeats the whole purpose. Epictetus reiterates the point:

“Show, don’t tell,” besides being good writing advice, is then an important Stoic principle concerning philosophy. One will always be tempted to make a philosophical and political point in order to show off or best another in argument, which of course defeats the whole purpose. Epictetus reiterates the point:

Never call yourself a philosopher, and don’t talk among laymen for the most part about philosophical principles, but act in accordance with those principles. At a banquet, for example, don’t talk about how one ought to eat, but eat as one ought. . . . And accordingly, if any talk should arise among laymen about some philosophical principle, keep silent for the most part, for there is great danger that you’ll simply vomit up what you haven’t properly digested. (Handbook, 46)

Epictetus is quite explicit that adoption of the Stoic way of life means a radical change, perhaps analogous to religious conversion. The change is so radical that one must be careful who one associates with. Obviously, one’s own spiritual practice will be all the greater insofar as one associates with like-minded people. Conversely, this also means one may have to abandon boorish old friends:

This is a point to which you should attend before all others, that you should never become so intimately associated with any of your former friends and acquaintances that you sink down to the same level as them; for otherwise, you’ll destroy yourself. But if this thought worms its way into your mind, that “I’ll seem churlish to him, and he won’t be as friendly to me as before,” remember that nothing is gained without cost, and that it is impossible for someone to remain the same as he was if he is no longer acting the same way. Choose, then, which you prefer: to be held in the same affection as before by your former friends by remaining as you used to be, or else become better than you were and no longer meet with the same affect . . . if you’re caught between two paths, you’ll incur a double penalty, since you’ll neither make progress as you ought nor acquire the things that you used to enjoy. (Discourses, 4.2.1-5).

The message is clear: the low spiritual and intellectual condition of “normies” is highly contagious, one must exercise the utmost caution. No doubt this bad condition has been severely aggravated and magnified by television and pop culture.

The message is clear: the low spiritual and intellectual condition of “normies” is highly contagious, one must exercise the utmost caution. No doubt this bad condition has been severely aggravated and magnified by television and pop culture.

By these metrics, I observe that the modern university experience is something of an anti-education: the stupidities of youth are exaggerated and made fashionable, rather than curtailed. The soul grows obese with pleasure and pride, rather than being moderated and cultivated. (I note in passing that Plato would no doubt be surprised, to not say worse, to learn that “academia” would grant degrees to 40 percent of the population.)

The Stoic will manage his social relations with moderation. He will economically support himself, honor his parents, and find a wife and raise of family of his own. Nonetheless, to the extent possible within the web of relations implied by his social role, he will live a philosophical life, and raise his peers by his example. In this, I should think, a shared spiritual practice with the wife and other immediate family is a great aid, to not say fundamental: by prayer, meditation, readings, song, and other rituals in common, one can lift up souls away from the sensuous and the frivolous, and towards principle.

References

Epictetus, Discourses, Fragments, Handbook, trans. Robin Hard (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

[1] [3] Epictetus scolds those who adopt the name Stoic but prefer to talk about philosophical principles than live them:

What difference does it make, in fact, whether you expound these teachings or those of another school? Sit down and give a technical account of the teachings of Epicurus, and perhaps you’ll give a better account than Epicurus himself! Why call yourself a Stoic, then; why mislead the crowd; why act the part of a Jew when you’re Greek? Don’t you know why it is that a person is called a Jew, Syrian, or Egyptian? And when we see someone hesitating between two creeds, we’re accustomed to say, “He is no Jew, but is merely acting the part.” But when he assumes the frame of mind of one who has been baptized and has made his choice, then he really is a Jew, and is called by that name. And so we too are baptized in name alone, while in fact being someone quite different, since we’re not in sympathy with our own doctrines, and are far from making any practical application of the principles we express, even though we take pride in knowing them. (Discourses, 2.9.19-22)

Epictetus repeatedly contrasts Middle-Eastern “Jews, Syrians, and Egyptians” with “Romans,” as culturally and perhaps ethnically others.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg