dimanche, 21 août 2011

Out of Africa? Races are more different than previously thought

Out of Africa?

Races are more different than previously thought.

Researchers led by Prof. Svante Pääbo at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig have placed a very large question mark over the currently fashionable “out-of-Africa” theory of the origins of modern man. They have done this by producing a partial genome from three fossil bones belonging to female Neanderthals from Vindija Cave in Croatia, and comparing it with the genomes of modern humans.

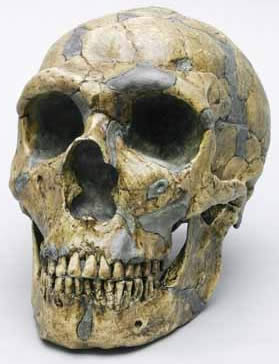

|

| Neanderthal Man: Our ancestor after all. |

|---|

Their initial results show that Neanderthals interbred with anatomically modern humans, mainly with the ancestors of peoples now found in Europe and Asia. This discovery both underlines the genetic differences between African and non-African populations and contradicts the pure, “out-of-Africa” version of human evolution, according to which all non-Africans living today are descended exclusively from migrants that left Africa less than 100,000 years ago. These migrants are said to have out-competed and eventually driven to extinction all other forms of homo and to have done so without interbreeding.

The authors of the Max Planck study note that Neanderthals, who lived in Europe and western Asia, were the closest evolutionary relatives of current humans, but went extinct about 30,000 years ago. They go on to note:

“Comparisons of the Neanderthal genome to the genomes of five present-day humans from different parts of the world identify a number of genomic regions that may have been affected by positive selection in ancestral modern humans, including genes involved in metabolism and in cognitive and skeletal development. We show that Neanderthals shared more genetic variants with present-day humans in Eurasia than with present-day humans in sub-Saharan Africa, suggesting that gene flow from Neanderthals into the ancestors of non-Africans occurred before the divergence of Eurasian groups from each other.” (Richard E. Green, Johannes Krause, et. al., A Draft Sequence of the Neanderthal Genome, Science, May 7, 2010).

In other words, Neanderthal genes remained in the human genome because they were beneficial, and are mainly found in non-African groups.

The traditional alternative to the “out-of-Africa” theory has been that different races evolved from earlier forms of homo in different parts of the world. That theory allows for a far longer period for the evolution of races. The great obstacle to this multi-regional theory has been genetic evidence taken from modern humans that points to a common ancestor who left Africa about 100,000 years ago. However, this judgment is based on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) — the DNA outside the nucleus — which shows no evidence of interbreeding. The Max Planck team, however, was the first to do a large-scale comparative study of nuclear DNA which, as they point out, “is composed of tens of thousands of recombining, and hence independently evolving, DNA segments that provide an opportunity to obtain a clearer picture of the relationship between Neanderthals and present-day humans.”

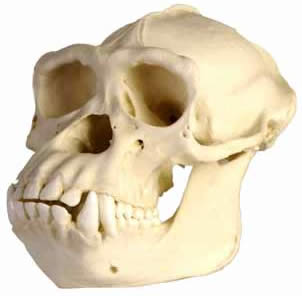

|

| Chimpanzee: Our closest living relative. |

|---|

The researchers note that their conclusions are tentative because they were able to reconstruct only about 60 percent of the Neanderthal genome. Much of this had to be carefully sifted because of contamination, especially by bacterial DNA. Nonetheless, where the Neanderthal genome could be compared to that of modern humans, the researchers found an estimated 99.7 percent match. They also found that the Neanderthal and modern genomes shared exactly the same degree of genetic similarity — 98.8 percent — with chimpanzees.

Of particular significance, however, is the result of comparing the Neanderthal genome with representatives of different modern races: “one San from Southern Africa, one Yoruba from West Africa, one Papua New Guinean, one Han Chinese, and one French from Western Europe.”

Non-Africans got a far larger genetic contribution from Neanderthals than Africans did:

“[I]ndividuals in Eurasia today carry regions in their genome that are closely related to those in Neanderthals and distant from other present-day humans. The data suggest that between 1 and 4 percent of the genomes of people in Eurasia are derived from Neanderthals. Thus, while the Neanderthal genome presents a challenge to the simplest version of an ‘out-of-Africa’ model for modern human origins, it continues to support the view that the vast majority of genetic variants that exist at appreciable frequencies outside Africa came from Africa with the spread of anatomically modern humans.”

Although the Neanderthal contribution is small, the fact that it survived at all suggests that it conferred an evolutionary advantage. The Max Planck team notes that those contributions were “involved in cognitive abilities and cranial morphology.” Neanderthals passed on to non-Africans whatever genetic advantages they had in these important areas.

It is possible that Neanderthals contributed more than the 1 to 4 percent calculated by the Max Planck researchers. Their Neanderthal genome was incomplete and the missing 40 percent may contain more genes present in modern humans. Even if Neanderthal genes form only a very small part of the modern non-African genome, small genetic differences can have important consequences. We share almost all of our DNA with chimps, yet are very different from them. It has become clear since the mapping of the human genome that the central importance of genes lies not in their quantity but in the way they interact. Many scientists expected that sequencing or decoding the human genome would lead to an understanding of how it works, but that has not been the case. Many mysteries remain, but it is clear that small differences can have profound effects.

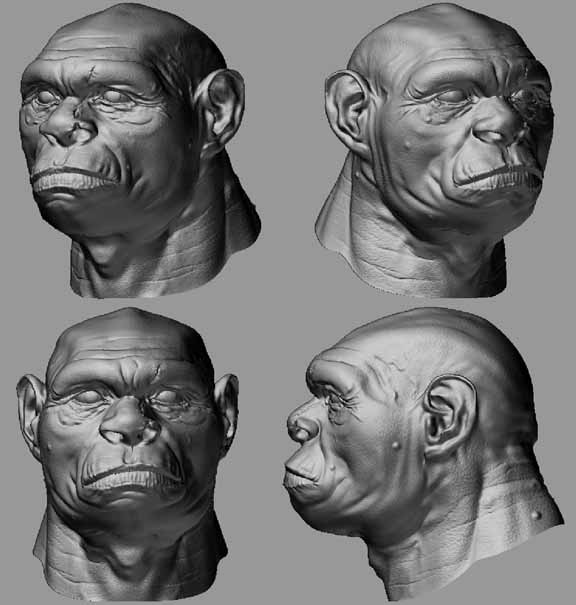

|

| Homo erectus: bred with modern humans? |

|---|

If modern humans bred with Neanderthals could there have been other mixtures of the varieties of homo throughout evolution? There was ample opportunity. Homo habilis is estimated to have existed from 2.3 to 1.4 million years ago, homo erectus to have lived between 1.9 million and 300,000 years ago (and possibly much later in isolated areas), Neanderthals from 400,000 years until 30,000 years ago, and homo sapiens from 250,000-150,000 years ago to the present. One promising candidate for interbreeding with modern humans is homo erectus. As the online encyclopedia science.jrank.org explains:

“Fossils of the species have been collected from South Africa, Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia, Algeria, Morocco, Italy, Germany, Georgia, India, China, and Indonesia. The oldest specimens come from Africa, the Caucasus, and Java and are dated at about 1.8 million years. These very early dates outside of Africa indicate that H. erectus dispersed across the Old World almost instantaneously, as soon as the species arose in Africa ... Homo erectus persisted very late in the Pleistocene epoch in Indonesia to possibly as late as 30,000 years ago, which suggests that the species survived in isolation while modern humans spread everywhere in the Old World.”

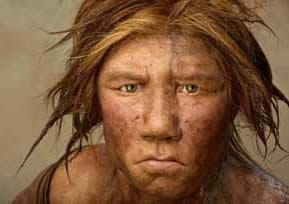

|

| National Geographic's Neanderthal woman. |

|---|

Just as this article was going to press, there were reports on the analysis of 30,000-year-old bones found by the Russians in a cave in Denisova in Siberia in 2008. The DNA, whose state of preservation has been called “miraculous,” proved to be distinct from both Neanderthals and modern humans, and researchers called the newly discovered hominids Denisovans. Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute studied this DNA as well, and determined that Denisovans also bred with modern humans — though not with those that remained in Africa.

The Denisovans were related to Neanderthals, and their common ancestors are thought to have left Africa some 400,000 or more years ago. One branch became Neanderthal in Western Eurasia and another became Denisovan in the East. Modern man appears to have encountered and bred with both groups, but only after leaving Africa. Specialists greeted the news about Denisovans with the expectation that yet more missing members of the human family tree could be rediscovered.

Indeed, the complexity and variety of the fossil record hints at what could have been considerable interbreeding. There has been a huge number of discoveries during the last century, but hominid remains are still very scarce and are often only a small fragment of a skeleton. Complete skeletons are like hens’ teeth. Moreover, when new fossils turn up, rather than clarify the record by filling in missing branches on the evolutionary tree, they tend to complicate matters. For example, they may show that a variety of homo was much older than previously thought or appeared in an unexpected place. Variability of fossils can also suggest intermediate forms that had not been anticipated, such as a specimen with traits characteristic of both homo erectus and Neanderthals. The difficulty in classifying human fossils and especially the existence of intermediate forms suggest interbreeding.

We are only now beginning to learn of some variants of homo that could have contributed genes to modern humans. In 2004, fossils of a dwarf species of homo — “Flores man,” who has been nicknamed “hobbit” — were found on the Indonesian island of Flores. Flores man is thought to have gone extinct about 12,000 years ago, so he certainly coexisted with modern humans.

Interbreeding between related varieties of homo would be more likely than that between related animals because even primitive homo had a large brain, which suggests self-consciousness, and, most probably, language. Animals mate in a largely automatic process prompted by various triggers: aural, chemical, condition of feathers and so on. Man, although not entirely without such triggers, adds conscious thought to mate selection. This allows humans to overcome the barriers of behavior and biology, and mate outside their subspecies or even species.

|

| The Vindija cave in Croatia. The bones that yielded the Max Planck Institute’s first Neanderthal genome were found here. |

|---|

Even today, tribal peoples may take women by force from other groups, often by organized raiding. Prehistoric man may have done the same, raising the possibility that interbreeding took place without the willing participation of the females.

At some point, of course, separate evolution would have produced separate species that were not mutually fertile. However, the social nature of homo and his probable ability to speak would tend to counteract the tendency to remain isolated from others for so long that breeding became impossible. It is worth adding that judging from the rapid spread of homo throughout Eurasia, man has been a very mobile animal. Such mobility would also make isolation difficult because even in a very sparsely populated world, the likelihood of encountering other bands of homo would be reasonably high.

How would different varieties of archaic humans have appeared to one another? Probably not so strange. There are certainly combinations of current-day racial types that appear more alien to each other than that would have Neanderthals and modern men.

In 2008, National Geographic released a likeness of a Neanderthal woman based on DNA from 43,000-year-old bones. The findings suggested that at least some Neanderthals had red hair, pale skin, and possibly freckles. These are particularly interesting traits because these were commonly noted by Romans who wrote about the inhabitants of Northern Europe. Today, many scientists would argue that if a Neanderthal were dressed in modern clothes he could walk down a busy street without attracting much attention.

If interbreeding did occur within the homo genus over several million years or even over hundreds of thousands of years, it would help explain the evolution of the group differences that now distinguish the different races. The purest “out-of-Africa” theory has always been implausible to those who think it does not allow enough time for races to emerge. There are differences of opinion among experts about time scales but the consensus is that modern man emerged from Africa at most 200,000 years ago. At 20 years per generation, this allows for only 10,000 generations to produce the enormous human variety that includes everything from Pygmies to Danes. Is that enough? Whites are supposed to have begun evolving independently for only 2,000 generations. Again, is that enough?

Realistic depictions of human beings go back to at least 3000 BC, and mummies, created deliberately or naturally, are often preserved well enough to determine racial type. The oldest North American mummy, for example, is of a 45-year-old male found in Churchill County, Nevada, and estimated to date from 7420 BC. These artifacts show that racial types have been stable for 5,000 to 10,000 years. If they have not changed in this time, it is reasonable to doubt that evolution could have changed migrants from Africa rapidly enough to produce today’s races.

Conclusion

The Max Planck Institute’s findings clearly show that the “out of Africa with no interbreeding” theory is incorrect. However, that does not necessarily mean that the ultimate origins of man do not lie in Africa or that the modern humans whose origins lie outside of Africa do not have a predominantly African heritage. What the Neanderthal and Denisovan genome research does confirm is that the human story is complicated.

The distribution of hominid fossil finds to date, the paleontological evidence, and the growing knowledge acquired through DNA analysis suggest that a plausible scenario for evolution is this: The story probably began in Africa, because this is the continent with the largest number of the most ancient fossils. Africans also show the greatest genetic variety, which suggests human evolution has been taking place there longer than anywhere else. However, early versions of homo moved out of Africa, perhaps as much as several million years ago. Some of these early versions evolved into creatures that approximated modern man, while at the same time evolution among African populations also brought them closer to modern man. At various points, African migrants emerged into Eurasia and interbred with forms of homo already there. There was no equivalent migration of Eurasians into Africa, or at least none that resulted in known interbreeding. The fossil record of mixtures of features from different hominids also suggests interbreeding.

|

| Neanderthal bones. |

|---|

Why was the rigid “out-of-Africa” theory so widely believed? Probably because it gave rise to the claim that “we are all Africans,” and because it suggested there were few biological differences between races. At the same time, the emphasis until recently on mtDNA rather than nuclear DNA, gave rise to dogmatic statements about distinct lineages and leant scientific backing to the idea.

“Out of Africa” supported the modern liberal view that race is a social construct and that the physical differences between races are trivial. In fact, racial differences are more dramatic than the differences between many closely related species of animals. There are objective racial differences in physiology, such as testosterone level, as well as differences in behavior and in average IQ. When we add to these differences the mix of genetic contributions from extinct or absorbed forms of homo, the liberal argument becomes even weaker. If homo sapiens were viewed as any other organism is viewed, it would no doubt be classified as several species rather than as a single species.

The group at the Max Planck Institute hopes to have decoded the entire Neanderthal and Denisovan genomes soon, and similar work is being done on other forms of ancient homo such as the “hobbits” from Flores. Decoding ancient DNA is difficult, but it is probable that the genomes of other early hominids, particularly that of homo erectus — the longest surviving and most widely dispersed ancient form of homo — will be decoded in the foreseeable future.

If such research shows that interbreeding was present throughout hominid evolution, or at least for substantial periods, then the multiregional theory is true to the extent that different races received genetic contributions from populations that developed outside of Africa for immense periods of time. If the genotypes of such ancient varieties such as homo erectus and homo heidelbergensis are mapped successfully, it may be found that Eurasians have a substantial selection of genes that are distant from those of Africans.

Even if that is not the case, a better understanding of genetics increasingly shows that small genetic differences cause significant physical differences. Whatever the case, the claim that “we are all Africans” has been significantly weakened, and a potent propaganda tool has been taken from the hands of the politically correct. ![]()

00:05 Publié dans anthropologie, Sciences | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | Tags : anthropologie, ethnologie, humanitépréhistorique, préhistoire, races, raciologie, groupes humains, polygénisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook