samedi, 30 mars 2013

Stalin’s Fight Against International Communism

Stalin’s Fight Against International Communism

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Editor’s Note:

This is the first chapter of Kerry Bolton’s new book Stalin: The Enduring Legacy [2] (London: Black House Publishing, 2012). The chapter is being reprinted as formatted in the book. Counter-Currents will also run a review of the book, which I highly recommend.

The notion that Stalin ‘fought communism’ at a glance seems bizarre. However, the contention is neither unique nor new. Early last century the seminal German conservative philosopher-historian Oswald Spengler stated that Communism in Russia would metamorphose into something distinctly Russian which would be quite different from the alien Marxist dogma that had been imposed upon it from outside. Spengler saw Russia as both a danger to Western Civilisation as the leader of a ‘coloured world-revolution’, and conversely as a potential ally of a revived Germany against the plutocracies. Spengler stated of Russia’s potential rejection of Marxism as an alien imposition from the decaying West that,

Race, language, popular customs, religion, in their present form… all or any of them can and will be fundamentally transformed. What we see today then is simply the new kind of life which a vast land has conceived and will presently bring forth. It is not definable in words, nor is its bearer aware of it. Those who attempt to define, establish, lay down a program, are confusing life with a phrase, as does the ruling Bolshevism, which is not sufficiently conscious of its own West-European, Rationalistic and cosmopolitan origin.[1]

Even as he wrote, Bolshevism in the USSR was being fundamentally transformed in the ways Spengler foresaw. The ‘rationalistic’ and ‘cosmopolitan’ origins of Bolshevism were soon being openly repudiated, and a new course was defined by Zhdanov and other Soviet eminences.

Contemporary with Spengler in Weimer Germany, there arose among the ‘Right’ the ‘National Bolshevik’ faction one of whose primary demands was that Germany align with the Soviet Union against the Western plutocracies. From the Soviet side, possibilities of an alliance with the ‘Right’ were far from discounted and high level Soviet sources cultivated contacts with the pro-Russian factions of the German Right including the National Bolsheviks.[2]

German-Soviet friendship societies included many conservatives. In Arbeitsgemeinschaft zum Studium der Sowjetrussichen Planwirtschaft (Arplan)[3] Conservative-Revolutionaries and National Bolsheviks comprised a third of the membership. Bund Geistige Berufe (BGB)[4] was founded in 1931 and was of particular interest to Soviet Russia, according to Soviet documents, which aimed ‘to attract into the orbit of our influence a range of highly placed intellectuals of rightist orientation’.[5]

The profound changes caused Konstantin Rodzaevsky, leader of the Russian Fascist Union among the White Russian émigrés at Harbin, to soberly reassess the USSR and in 1945 he wrote to Stalin:

Not all at once, but step by step we came to this conclusion. We decided that: Stalinism is exactly what we mistakenly called ‘Russian Fascism’. It is our Russian Fascism cleansed of extremes, illusions, and errors.[6]

In the aftermath of World War II many German war veterans, despite the devastating conflagration between Germany and the USSR, and the rampage of the Red Army across Germany with Allied contrivance, were vociferous opponents of any German alliance with the USA against the USSR. Major General Otto E Remer and the Socialist Reich Party were in the forefront of advocating a ‘neutralist’ line for Germany during the ‘Cold War’, while one of their political advisers, the American Spenglerian philosopher Francis Parker Yockey, saw Russian occupation as less culturally debilitating than the ‘spiritual syphilis’ of Hollywood and New York, and recommended the collaboration of European rightists and neo-Fascists with the USSR against the USA.[7] Others of the American Right, such as the Yockeyan and Spenglerian influenced newspaper Common Sense, saw the USSR from the time of Stalin as the primary power in confronting Marxism, and they regarded New York as the real ‘capitol’ of Marxism.[8]

What might be regarded by many as an ‘eccentric’ element from the Right were not alone in seeing that the USSR had undergone a revolutionary transformation. Many of the Left regarded Stalin’s Russia as a travesty of Marxism. The most well-known and vehement was of course Leon Trotsky who condemned Stalin for having ‘betrayed the revolution’ and for reversing doctrinaire Marxism. On the other hand, the USA for decades supported Marxists, and especially Trotskyites, in trying to subvert the USSR during the Cold War. The USA, as the columnists at Common Sense continually insisted, was promoting Marxism, while Stalin was fighting it. This dichotomy between Russian National Bolshevism and US sponsored international Marxism was to having lasting consequences for the post-war world up to the present.

Stalin Purges Marxism

The Moscow Trials purging Trotskyites and other veteran Bolsheviks were merely the most obvious manifestations of Stalin’s struggle against alien Marxism. While much has been written condemning the trials as a modern day version of the Salem witch trials, and while the Soviet methods were often less than judicious the basic allegations against the Trotskyites et al were justified. The trials moreover, were open to the public, including western press, diplomats and jurists. There can be no serious doubt that Trotskyites in alliance with other old Bolsheviks such as Zinoviev and Kameneff were complicit in attempting to overthrow the Soviet state under Stalin. That was after all, the raison d’etre of Trotsky et al, and Trotsky’s hubris could not conceal his aims.[9]

The purging of these anti-Stalinist co-conspirators was only a part of the Stalinist fight against the Old Bolsheviks. Stalin’s relations with Lenin had not been cordial, Lenin accusing him of acting like a ‘Great Russian chauvinist’.[10] Indeed, the ‘Great Russians’ were heralded as the well-spring of Stalin’s Russia, and were elevated to master-race like status during and after the ‘Great Patriotic War’ against Germany. Lenin, near death, regarded Stalin’s demeanour as ‘offensive’, and as not showing automatic obedience. Lenin wished for Stalin to be removed as Bolshevik Party General Secretary.[11]

Dissolving the Comintern

The most symbolic acts of Stalin against International Communism were the elimination of the Association of Old Bolsheviks, and the destruction of the Communist International (Comintern). The Comintern, or Third International, was to be the basis of the world revolution, having been founded in 1919 in Moscow with 52 delegates from 25 countries.[12] Zinoviev headed the Comintern’s Executive Committee.[13] He was replaced by Bukharin in 1926.[14] Both Zinonviev and Bukharin were among the many ‘Old Bolsheviks’ eliminated by Stalin.

Stalin regarded the Comintern with animosity. It seemed to function more as an enemy agency than as a tool of Stalin, or at least that is how Stalin perceived the organisation. Robert Service states that Dimitrov, the head of the Comintern at the time of its dissolution, was accustomed to Stalin’s accusations against it. In 1937 Stalin had barked at him that ‘all of you in Comintern are hand in glove with the enemy’.[15] Dimitrov must have wondered how long he had to live.[16]

Instead of the Communist parties serving as agents of the world revolution, in typically Marxist manner, and the purpose for founding the Comintern, the Communist parties outside Russia were expected to be nationally oriented. In 1941 Stalin stated of this:

The International was created in Marx’s time in the expectation of an approaching international revolution. Comintern was created in Lenin’s time at an analogous moment. Today, national tasks emerge for each country as a supreme priority. Do not hold on tight to what was yesterday.[17]

This was a flagrant repudiation of Marxist orthodoxy, and places Stalinism within the context of National Bolshevism.

The German offensive postponed Stalin’s plans for the elimination of the Comintern, and those operatives who had survived the ‘Great Purge’ were ordered to Ufa, South of the Urals. Dimitrov was sent to Kuibyshev on the Volga. After the Battle of Stalingrad, Stalin returned to the issue of the Comintern, and told Dimitrov on 8 May 1943 to wind up the organisation. Dimitrov was transferred to the International Department of the Bolshevik Party Central Committee.[18] Robert Service suggests that this could have allayed fears among the Allies that Stalin would pursue world revolution in the post-war world. However, Stalin’s suspicion of the Comintern and the liquidation of many of its important operatives indicate fundamental belligerence between the two. In place of proletarian international solidarity, Stalin established an All-Slavic Committee[19] to promote Slavic folkish solidarity, although the inclusion of the Magyars[20] was problematic.

Stalin throughout his reign undertook a vigorous elimination of World Communist leaders. Stalin decimated communist refugees from fascism living in the USSR. While only 5 members of the Politburo of the German Communist Party had been killed under Hitler, in the USSR 7 were liquidated, and 41 out of 68 party leaders. The entire Central Committee of the Polish Communist Party in exile were liquidated, and an estimated 5000 party members were killed. The Polish Communist Party was formally dissolved in 1938. 700 Comintern headquarters staff were purged.[21]

Among the foreign Communist luminaries who were liquidated was Bela Kun, whose psychotic Communist regime in Hungary in 1919 lasted 133 days. Kun fled to the Soviet Union where he oversaw the killing of 50,000 soldiers and civilians attached to the White Army under Wrangle, who had surrendered after being promised amnesty. Kun was a member of the Executive Committee of the Comintern. A favourite of Lenin’s, this bloody lunatic served as a Comintern agent in Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia during the 1920s. In 1938 he was brought before a tribunal and after a brief trial was executed the same day.[22]

Another action of great symbolism was Stalin’s moves against the ‘Old Bolsheviks’, the veterans of the 1917 Revolution. Leon Sedov, Leon Trotsky’s son, in his pamphlet on the Great Purge of the late 1930s, waxed indignant that Stalin ‘coldly orders the shooting of Bolsheviks, former leaders of the Party and the Comintern, and heroes of the Civil War’.[23] ‘The Association of Old Bolsheviks and that of the former political prisoners has been dissolved. They were too strong a reminder of the “cursed” revolutionary past’.[24]

In place of the Comintern the Cominform was established in 1947, for the purpose of instructing Communist parties to campaign against the Marshall Aid programme that was designed to bring war-ravished Europe under US hegemony. ‘European communism was to be redirected’ towards maintaining the gains of the Red Army during World War II. ‘Communist parties in Western Europe could stir up trouble’, against the USA. The Cominform was far removed from being a resurrection of the old Comintern. As to who was invited to the inaugural meeting held at a secluded village in Poland, ‘Stalin… refused a request from Mao Zedong, who obviously thought that the plan was to re-establish the Communist International’. The Spanish and Portuguese parties were not invited, nor were the British, or the Greek Communist Party, which was fighting a civil war against the royalists.[25]

The extent of the ‘fraternity’ between the USSR and the foreign Communists can be gauged from the delegates having not been given prior knowledge of the agenda, and being ‘treated like detainees on arrival’. While Soviet delegates Malenkov and Zhdanov kept in regular communication with Stalin, none of the other delegates were permitted communication with the outside world.[26]

Repudiation of Marxist Doctrine

The implementation of Marxism as a policy upon which to construct a State was of course worthless, and Stalin reversed the doctrinaire Marxism that he had inherited from the Lenin regime. Leon Sedov indignantly stated of this:

In the most diverse areas, the heritage of the October revolution is being liquidated. Revolutionary internationalism gives way to the cult of the fatherland in the strictest sense. And the fatherland means, above all, the authorities. Ranks, decorations and titles have been reintroduced. The officer caste headed by the marshals has been reestablished. The old communist workers are pushed into the background; the working class is divided into different layers; the bureaucracy bases itself on the ‘non-party Bolshevik’, the Stakhanovist, that is, the workers’ aristocracy, on the foreman and, above all, on the specialist and the administrator. The old petit-bourgeois family is being reestablished and idealized in the most middle-class way; despite the general protestations, abortions are prohibited, which, given the difficult material conditions and the primitive state of culture and hygiene, means the enslavement of women, that is, the return to pre-October times. The decree of the October revolution concerning new schools has been annulled. School has been reformed on the model of tsarist Russia: uniforms have been reintroduced for the students, not only to shackle their independence, but also to facilitate their surveillance outside of school. Students are evaluated according to their marks for behaviour, and these favour the docile, servile student, not the lively and independent schoolboy. The fundamental virtue of youth today is the ‘respect for one’s elders’, along with the ‘respect for the uniform’. A whole institute of inspectors has been created to look after the behaviour and morality of the youth.[27]

This is what Leon Sedov, and his father, Leon Trotsky, called the ‘Bonapartist character of Stalinism’.[28] And that is precisely what Stalin represents in history: the Napoleon of the Bolshevik Revolution who reversed the Marxian doctrinal excrescences in a manner analogous to that of Napoleon’s reversal of Jacobin fanaticism after the 1789 French Revolution. Underneath the hypocritical moral outrage about Stalinist ‘repression’, etc.,[29] a number of salient factors emerge regarding Stalin’s repudiation of Marxist-Leninist dogma:

- The ‘fatherland’ or what was called again especially during World War II, ‘Holy Mother Russia’, replaced international class war and world revolution.

- Hierarchy in the military and elsewhere was re-established openly rather than under a hypocritical façade of soviet democracy and equality.

- A new technocratic elite was established, analogous to the principles of German ‘National Bolshevism’.

- The traditional family, the destruction of which is one of the primary aims of Marxism generally[30] and Trotskyism specifically,[31] was re-established.

- Abortion, the liberalisation of which was heralded as a great achievement in woman’s emancipation in the early days of Bolshevik Russia, was reversed.

- A Czarist type discipline was reintroduced to the schools; Leon Sedov condemned this as shackling the free spirit of youth, as if there were any such freedom under the Leninist regime.

- ‘Respect for elders’ was re-established, again anathema to the Marxists who seek the destruction of family life through the alienation of children from parents.[32]

What the Trotskyites and other Marxists object to was Stalin’s establishment the USSR as a powerful ‘nation-state’, and later as an imperial power, rather than as a citadel for world revolution. However, the Trotskyites, more than any other Marxist faction, allied themselves to American imperialism in their hatred of Stalinist Russia, and served as the most enthusiastic partisans of the Cold War.[33] Sedov continued:

Stalin not only bloodily breaks with Bolshevism, with all its traditions and its past, he is also trying to drag Bolshevism and the October revolution through the mud. And he is doing it in the interests of world and domestic reaction. The corpses of Zinoviev and Kamenev must show to the world bourgeoisie that Stalin has broken with the revolution, and must testify to his loyalty and ability to lead a nation-state. The corpses of the old Bolsheviks must prove to the world bourgeoisie that Stalin has in reality radically changed his politics, that the men who entered history as the leaders of revolutionary Bolshevism, the enemies of the bourgeoisie, – are his enemies also. Trotsky, whose name is inseparably linked with that of Lenin as the leader of the October revolution, Trotsky, the founder and leader of the Red Army; Zinoviev and Kamenev, the closest disciples of Lenin, one, president of the Comintern, the other, Lenin’s deputy and member of the Politburo; Smirnov, one of the oldest Bolsheviks, conqueror of Kolchak—today they are being shot and the bourgeoisie of the world must see in this the symbol of a new period. This is the end of the revolution, says Stalin. The world bourgeoisie can and must reckon with Stalin as a serious ally, as the head of a nation-state…. Stalin has abandoned long ago the course toward world revolution.[34]

As history shows, it was not Stalin to whom the ‘world bourgeoisie’ or more aptly, the world plutocracy, looked on as an ally, but leading Trotskyites whose hatred of Stalin and the USSR made them vociferous advocates of American foreign policy.

Family Life Restored

Leon Trotsky is particularly interesting in regard to what he saw as the ‘revolution betrayed’ in his condemnation of Stalinist policies on ‘youth, family, and culture’. Using the term ‘Thermidor’, taken from the French revolutionary era, in his description of Stalinism vis-à-vis the Bolshevik revolution, Trotsky began his critique on family, generational and gender relations. Chapter 7 of The Revolution Betrayed is worth reading in its entirety as an over-view of how Stalin reversed Marxism-Leninism. Whether that is ‘good’ or ‘bad’ is, of course, left to the subjectivity of the reader.[35]

The primary raison d’etre of Marxism for Trotsky personally seems to have been the destruction of religion and of family (as it was for Marx).[36] Hence, the amount of attention Trotsky gives to lamenting the return to traditional family relations under Stalin:

The revolution made a heroic effort to destroy the so-called ‘family hearth’ – that archaic, stuffy and stagnant institution in which the woman of the toiling classes performs galley labor from childhood to death. The place of the family as a shut-in petty enterprise was to be occupied, according to the plans, by a finished system of social care and accommodation: maternity houses, creches, kindergartens, schools, social dining rooms, social laundries, first-aid stations, hospitals, sanatoria, athletic organizations, moving-picture theaters, etc. The complete absorption of the housekeeping functions of the family by institutions of the socialist society, uniting all generations in solidarity and mutual aid, was to bring to woman, and thereby to the loving couple, a real liberation from the thousand-year-old fetters. Up to now this problem of problems has not been solved. The forty million Soviet families remain in their overwhelming majority nests of medievalism, female slavery and hysteria, daily humiliation of children, feminine and childish superstition. We must permit ourselves no illusions on this account. For that very reason, the consecutive changes in the approach to the problem of the family in the Soviet Union best of all characterize the actual nature of Soviet society and the evolution of its ruling stratum.[37]

Marxism, behind the façade of women’s emancipation, ridicules the traditional female role in the family as ‘galley labour’, but does so for the purpose of delivering women to the ‘galley labour’ of the Marxist state. The Marxist solution is to take the child from the parents and substitute parental authority for the State via childcare. As is apparent today, the Marxist ideal regarding the family and children is the same as that of big capitalism. It is typical of the manner by which Marxism, including Communism, converges with plutocracy, as Spengler pointed out soon after the 1917 Revolution in Russia.[38]

Trotsky states, ‘you cannot “abolish” the family; you have to replace it’. The aim was to replace the family with the state apparatus: ‘During the lean years, the workers wherever possible, and in part their families, ate in the factory and other social dining rooms, and this fact was officially regarded as a transition to a socialist form of life’. Trotsky decries the reversal by Stalin of this subversion of the family hearth: ‘The fact is that from the moment of the abolition of the food-card system in 1935, all the better placed workers began to return to the home dining table’. Women as mothers and wives were retuning to the home rather than being dragooned into factories, Trotsky getting increasingly vehement at these reversals of Marxism:

Back to the family hearth! But home cooking and the home washtub, which are now half shamefacedly celebrated by orators and journalists, mean the return of the workers’ wives to their pots and pans that is, to the old slavery.[39]

The original Bolshevik plan was for a new slavery where all would be bound to the factory floor regardless of gender, a now familiar aim of global capitalism, behind the façade of ‘equality’. Trotsky lamented that the rural family was even stronger: ‘The rural family, bound up not only with home industry but with agriculture, is infinitely more stable and conservative than that of the town’. There had been major reversals in the collectivisation of the peasant families: they were again obtaining most of their food from private lots rather than collectivised farms, and ‘there can no longer be any talk of social dining rooms’. ‘Thus the midget farms, [were] creating a new basis for the domestic hearthstone…’[40]

The pioneering of abortion rights by the Leninist regime was celebrated as a great achievement of Bolshevism, which was, however, reversed by Stalin with the celebration instead of motherhood. In terms that are today conventional throughout the Western world, Trotsky stated that due to the economic burden of children upon women,

…It is just for this reason that the revolutionary power gave women the right to abortion, which in conditions of want and family distress, whatever may be said upon this subject by the eunuchs and old maids of both sexes, is one of her most important civil, political and cultural rights. However, this right of women too, gloomy enough in itself, is under the existing social inequality being converted into a privilege.[41]

The Old Bolsheviks demanded abortion as a means of ‘emancipating women’ from children and family. One can hardly account for the Bolshevik attitude by an appeal to anyone’s ‘rights’ (sic). The answer to the economic hardship of childbearing was surely to eliminate the causes of the hardship. In fact, this was the aim of the Stalinists, Trotsky citing this in condemnation:

One of the members of the highest Soviet court, Soltz, a specialist on matrimonial questions, bases the forthcoming prohibition of abortion on the fact that in a socialist society where there are no unemployed, etc., etc., a woman has no right to decline ‘the joys of motherhood’.[42]

On June 27 1936 a law was passed prohibiting abortion, which Trotsky called the natural and logical fruit of a ‘Thermidorian reaction’.[43] The redemption of the family and motherhood was damned perhaps more vehemently by Trotsky than any other aspect of Stalinism as a repudiation of the ‘ABCs of Communism’, which he stated includes ‘getting women out of the clutches of the family’.

Everybody and everything is dragged into the new course: lawgiver and litterateur, court and militia, newspaper and schoolroom. When a naive and honest communist youth makes bold to write in his paper: ‘You would do better to occupy yourself with solving the problem how woman can get out of the clutches of the family’, he receives in answer a couple of good smacks and – is silent. The ABCs of Communism are declared a ‘leftist excess’. The stupid and stale prejudices of uncultured philistines are resurrected in the name of a new morale. And what is happening in daily life in all the nooks and corners of this measureless country? The press reflects only in a faint degree the depth of the Thermidorian reaction in the sphere of the family.[44]

A ‘new’ or what we might better call traditional ‘morale’ had returned. Marriage and family were being revived in contrast to the laws of early Bolshevik rule:

The lyric, academical and other ‘friends of the Soviet Union’ have eyes in order to see nothing. The marriage and family laws established by the October revolution, once the object of its legitimate pride, are being made over and mutilated by vast borrowings from the law treasuries of the bourgeois countries. And as though on purpose to stamp treachery with ridicule, the same arguments which were earlier advanced in favor of unconditional freedom of divorce and abortion – ‘the liberation of women’, ‘defense of the rights of personality’, ‘protection of motherhood’ – are repeated now in favor of their limitation and complete prohibition.[45]

Trotsky proudly stated that the Bolsheviks had sought to alienate children from their parents, but under Stalin parents resumed their responsibilities as the guardians of their children’s welfare, rather than the role being allotted to factory crèches. It seems, that in this respect at least, Stalinist Russia was less a Marxian-Bolshevik state than the present day capitalist states which insist that mothers should leave their children to the upbringing of crèches while they are forced to work; and ironically those most vocal in demanding such polices are often regarded as ‘right-wing’.

Trotsky lauded the policy of the early Bolshevik state, to the point where the state withdrew support from parents

While the hope still lived of concentrating the education of the new generations in the hands of the state, the government was not only unconcerned about supporting the authority of the ‘elders’, and, in particular of the mother and father, but on the contrary tried its best to separate the children from the family, in order thus to protect them from the traditions of a stagnant mode of life.[46]

Trotsky portrayed the early Bolshevik experiments as the saving of children from ‘drunken fathers or religious mothers’; ‘a shaking of parental authority to its very foundations’.[47]

Stalinist Russia also reversed the original Bolshevik education policy that had been based on ‘progressive’ American concepts and returned authority to the schools. In speaking of the campaign against decadence in music,[48] Andrei Zhdanov, Stalin’s cultural adviser, recalled the original Bolshevik education policy, and disparaged it as ‘very leftish’:

At one time, you remember, elementary and secondary schools went in for the ‘laboratory brigade’ method and the ‘Dalton plan’,[49] which reduced the role of the teacher in the schools to a minimum and gave each pupil the right to set the theme of classwork at the beginning of each lesson. On arriving in the classroom, the teacher would ask the pupils ‘What shall we study today?’ The pupils would reply: ‘Tell us about the Arctic’, ‘Tell us about the Antarctic’, ‘Tell us about Chapayev’, ‘Tell us about Dneprostroi’. The teacher had to follow the lead of these demands. This was called the ‘laboratory brigade method’, but actually it amounted to turning the organisation of schooling completely topsy-turvy. The pupils became the directing force, and the teacher followed their lead. Once we had ‘loose-leaf textbooks’, and the five point system of marks was abandoned. All these things were novelties, but I ask you, did these novelties stand for progress?

The Party cancelled all these ‘novelties’, as you know. Why? Because these ‘novelties’, in form very ‘leftish’, were in actual fact extremely reactionary and made for the nullification of the school.[50]

One observer visiting the USSR explained:

Theories of education were numerous. Every kind of educational system and experiment was tried—the Dalton Plan, the Project Method, the Brigade Laboratory and the like. Examinations were abolished and then reinstated; though with a vital difference. Examinations in the Soviet Union serve as a test for scholarship, not as a door to educational privilege.[51]

In particular the amorality inherent in Marxism was reversed under Stalinism. Richard Overy sates of this process:

Changing attitudes to behaviour and social environment under Stalin went hand-in-hand with a changing attitude towards the family… Unlike family policy in the 1920s, which assumed the gradual breakdown of the conventional family unit as the state supplied education and social support of the young, and men and women sought more collective modes of daily life, social policy under Stalin reinstated the family as the central social unit, and proper parental care as the model environment for the new Soviet generation. Family policy was driven by two primary motives: to expand the birth rate and to provide a more stable social context in a period of rapid social change. Mothers were respected as heroic socialist models in their own right and motherhood was defined as a socialist duty. In 1944 medals were introduced for women who had answered the call: Motherhood medal, Second Class for five children, First Class for six; medals of Motherhood Glory in three classes for seven, eight or nine offspring, for ten or more, mothers were justly nominated Heroine Mother of the Soviet Union, and an average of 5,000 a year won this highest accolade, and a diploma from the Soviet President himself.[52]

No longer were husband and wife disparaged as the ‘drunken father’ and the ‘religious mother’, from whom the child must be ‘emancipated’ and placed under state jurisdiction, as Trotsky and the other Old Bolshevik reprobates attempted. Professor Overy states, rather, that ‘the ideal family was defined in socialist-realist terms as large, harmonious and hardworking’. ‘Free love and sexual licence’, the moral nihilism encouraged by Bolshevism during its early phase, was being described in Pravda in 1936 as ‘altogether bourgeois’.[53]

In 1934 traditional marriage was reintroduced, and wedding rings, banned since the 1920s, were again produced. The austere and depressing atmosphere of the old Bolshevik marriage ceremony was replaced with more festive and prolonged celebration. Divorce, which the Bolsheviks had made easy, causing thousands of men to leave their families, was discouraged by raising fees. Absentee fathers were obliged to pay half their earnings for the upkeep of their families. Homosexuality, decriminalised in 1922, was recriminalised in 1934. Abortion, legalised in 1920, was outlawed in 1936, with abortionists liable to imprisonment from one to three years, while women seeking termination could be fined up to 300 roubles.[54] The exception was that those with hereditary illnesses could apply for abortion.[55]

Kulturkampf

The antithesis between Marxist orthodoxy and Stalinism is nowhere better seen than in the attitudes towards the family, as related above, and culture.

Andrei Zhdanov, the primary theoretician on culture in Stalinist Russia, was an inveterate opponent of ‘formalism’ and modernism in the arts. ‘Socialist-realism’, as Soviet culture was termed from 1932,[56] was formulated that year by Maxim Gorky, head of the Union of Soviet Writers.[57] It was heroic, folkish and organic. The individual artist was the conveyor of the folk-soul, in contrast to the art of Western decline, dismissively described in the USSR as ‘bourgeoisie formalism’.[58]

The original Bolshevik vision of a mass democratic art, organised as ‘Proletkult’, which recruited thousands of workers to be trained as artists and writers, as one would train workers to operate a factory conveyor built, was replaced by the genius of the individual expressing the soul of the people. While in The West the extreme Left and its wealthy patrons championed various forms of modernism,[59] in the USSR they were marginalized at best, resulting in the suicide for example of the Russian ‘Constructivist’ Mayakovsky. The revitalisation of Russian-Soviet art received its primary impetus in 1946 with the launching of Zhdanovschina.[60]

The classical composers from the Czarist era, such as Tchaikovsky, Glinka sand Borodin, were revived, after being sidelined in the early years of Bolshevism in favour of modernism, as were great non-Russian composers such as Beethoven, Brahms and Schubert.[61] Maxim Gorky continued to be celebrated as ‘the founder of Soviet literature and he continued to visit the USSR, despite his having moved to Fascist Italy. He returned to Russia in 1933.[62] Modernists who had been fêted in the early days of Bolshevism, such as the playwright, Nikolai Erdman, were relegated to irrelevance by the 1930s.[63]

Jazz and the associated types of dancing were condemned as bourgeoisie degeneracy.[64]

Zhdanov’s speech to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolshevik) intended primarily to lay the foundations of Soviet music, represents one of the most cogent recent attempts to define culture. Other than some sparse references to Marx, Lenin and internationalism, the Zhdanov speech should rank alongside T S Eliot’s Notes Towards A Definition of Culture[65] as a seminal conservative statement on culture. The Zhandov speech also helped set the foundation for the campaign against ‘rootless cosmopolitanism’ that was launched several years later. Zhdandov’s premises for a Soviet music were based on the classical and the organic connexion with the folk, striving for excellence, and expressing lofty values, rejecting modernism as detached from folk and tradition.

And, indeed, we are faced with a very acute, although outwardly concealed struggle between two trends in Soviet music. One trend represents the healthy, progressive principle in Soviet music, based upon recognition of the tremendous role of the classical heritage, and, in particular, the traditions of the Russian musical school, on the combination of lofty idea content in music, its truthfulness and realism, with profound, organic ties with the people and their music and songs – all this combined with a high degree of professional mastery. The other trend is that of formalism, which is alien to Soviet art, and is marked by rejection of the classical heritage under the guise of seeming novelty, by rejection of popular music, by rejection of service to the people in preference for catering to the highly individualistic emotions of a small group of select aesthetes.[66]

While some in the Proletkult, founded in 1917 were of Futurist orientation, declaring like the poet Vladimir Kirillov, for example, that ‘In the name of our tomorrow, we will burn Raphael, we will destroy museums, we will trample the flowers of art’, the Proletkult organisation was abolished in 1932,[67] and Soviet culture was re-established on classical foundations. Khdanov was to stress the classical heritage combined with the Russian folk traditions, as the basis for Soviet culture in his address:

Let us examine the question of attitude towards the classical heritage, for instance. Swear as the above-mentioned composers may that they stand with both feet on the soil of the classical heritage, there is nothing to prove that the adherents of the formalistic school are perpetuating and developing the traditions of classical music. Any listener will tell you that the work of the Soviet composers of the formalistic trend is totally unlike classical music. Classical music is characterised by its truthfulness and realism, by the ability to attain to unity of brilliant artistic form with profound content, to combine great mastery with simplicity and comprehensibility. Classical music in general, and Russian classical music in particular, are strangers to formalism and crude naturalism. They are marked by lofty idea content, based upon recognition of the musical art of the peoples as the wellspring of classical music, by profound respect and love for the people, their music and songs.[68]

Zhdanov’s analysis of modernism in music and his definition of classic culture is eminently relevant for the present state of Western cultural degeneracy:

What a step back from the highroad of musical development our formalists make when, undermining the bulwarks of real music, they compose false and ugly music, permeated with idealistic emotions, alien to the wide masses of people, and catering not to the millions of Soviet people, but to the few, to a score or more of chosen ones, to the ‘elite’! How this differs from Glinka, Chaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Dargomyjsky and Mussorgsky, who regarded the ability to express the spirit and character of the people in their works as the foundation of their artistic growth. Neglect of the demands of the people, their spirit and art means that the formalistic trend in music is definitely anti-popular in character.[69]

Zhdanov addressed a tendency in Russia that has thrived in The West: that of the ever new and the ‘theoretical’ that is supposedly so profound as to be beyond the understanding of all but depraved, pretentious or commodity-driven artistic coteries in claiming that only future generations will widely understand these artistic vanguards. However, Stalinist Russia repudiated the nonsense; and exposed the emperor as having no clothes:

It is simply a terrible thing if the ‘theory’ that ‘we will be understood fifty or a hundred years hence’, that ‘our contemporaries may not understand us, but posterity will’ is current among a certain section of Soviet composers. If this altitude has become habitual, it is a very dangerous habit.[70]

For Zhdanov, and consequently for the USSR, the classics were a folkish manifestation arising from the soul of the Russian people, rather than being dismissed in Marxian manner as merely products of bourgeoisie culture. In fact, as indicated previously, it was modernism that was regarded as a manifestation of ‘bourgeois decadence’. Zhandov castigated the modernists as elitist, aloof, or better said, alienated from the folk. On the other hand the great Russian classicists, despite their class origins, were upheld as paragons of the Russian folk culture:

Remember how the classics felt about the needs of the people. We have begun to forget in what striking language the composers of the Big Five,[71] and the great music critic Stasov, who was affiliated with them, spoke of the popular element in music. We have begun to forget Glinka’s wonderful words about the ties between the people and artists: “Music is created by the people and we artists only arrange it.” We are forgetting that the great master did not stand aloof from any genres if these genres helped to bring music closer to the wide masses of people. You, on the other hand, hold aloof even from such a genre as the opera; you regard the opera as secondary, opposing it to instrumental symphony music, to say nothing of the fact that you look down on song, choral and concert music, considering it a disgrace to stoop to it and satisfy the demands of the people. Yet Mussorgsky adapted the music of the Hopak, while Glinka used the Komarinsky for one of his finest compositions. Evidently, we shall have to admit that the landlord Glinka, the official Serov and the aristocrat Stasov were more democratic than you. This is paradoxical, but it is a fact. Solemn vows that you are all for popular music are not enough. If you are, why do you make so little use of folk melodies in your musical works? Why are the defects, which were criticised long ago by Serov, when he said that ‘learned’, that is, professional, music was developing parallel with and independently of folk music, repeating themselves? Can we really say that our instrumental symphony music is developing in close interaction with folk music – be it song, concert or choral music? No, we cannot say that. On the contrary, a gulf has unquestionably arisen here as the result of the underestimation of folk music by our symphony composers. Let me remind you of how Serov defined his attitude to folk music. I am referring to his article The Music of South Russian Songs in which he said: ‘Folk songs, as musical organisms, are by no means the work of individual musical talents, but the productions of a whole nation; their entire structure distinguishes them from the artificial music written in conscious imitation of previous examples, written as the products of definite schools, science, routine and reflexes. They are flowers that grow naturally in a given locale, that have appeared in the world of themselves and sprung to full beauty without the least thought of authorship or composition, and consequently, with little resemblance to the hothouse products of learned compositional activity’. That is why the naivete of creation, and that (as Gogol aptly expressed it in Dead Souls) lofty wisdom of simplicity which is the main charm and main secret of every artistic work are most strikingly manifest in them.[72]

It is notable that Zhdanov emphasised the basis of culture as an organic flowering from the nation. Of painting Zhandov again attacked the psychotic ‘leftist’ influences:

Or take this example. An Academy of Fine Arts was organised not so long ago. Painting is your sister, one of the muses. At one time, as you know, bourgeois influences were very strong in painting. They cropped up time and again under the most ‘leftist’ flags, giving themselves such tags as futurism, cubism, modernism; ‘stagnant academism’ was ‘overthrown’, and novelty proclaimed. This novelty expressed itself in insane carryings on, as for instance, when a girl was depicted with one head on forty legs, with one eye turned towards us, and the other towards Arzamas. How did all this end? In the complete crash of the ‘new trend’. The Party fully restored the significance of the classical heritage of Repin, Briullov, Vereshchagin, Vasnetsov and Surikov. Did we do right in reinstating the treasures of classical painting, and routing the liquidators of painting?[73]

The extended discussion here on Russian culture under Stalin is due to the importance that the culture-war between the USSR and the USA took, having repercussions that were not only world-wide but lasting.

Notes

[1] Oswald Spengler, The Hour of Decision (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1963), 61.

[2] K R Bolton, ‘Jünger and National-Bolshevism’ in Jünger: Thoughts & Perspectives Vol. XI (London: Black Front Press, 2012).

[3] Association for the Study of the Planned Economy of Soviet Russia.

[4] League of Professional Intellectuals.

[5] K R Bolton, ‘Jünger and National-Bolshevism’, op. cit.

[6] Cited by John J Stephan, The Russian Fascists (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1978), 338.

[7] K R Bolton, ‘Francis Parker Yockey: Stalin’s Fascist Advocate’, International Journal of Russian Studies, Issue No. 6, 2010, http://www.radtr.net/dergi/sayi6/bolton6.htm [3]

[8] K R Bolton, ‘Cold War Axis: Soviet Anti-Zionism and the American Right’’ see Appendix II below.

[9] See Chapter III: ‘The Moscow Trials in Historical Context’.

[10] R Service, Comrades: Communism: A World History (London: Pan MacMillan, 2008), 97.

[11] Ibid., 98.

[12] Ibid., 107.

[13] Ibid., 109.

[14] Ibid., 116.

[15] G Dimitrov, Dimitrov and Stalin 1934-1943: Letters from the Soviet Archives, 32, cited by R Service, ibid., 220.

[16] R Service, ibid., 220.

[17] G Dimitrov, op. cit., cited by Service, ibid., 221.

[18] R Service, ibid., 222.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Hungarians.

[21] Richard Overy, The Dictators: Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Russia (London: Allen Lane, 2004), 201.

[22] L I Shvetsova, et al. (eds.), Rasstrel’nye spiski: Moskva, 1937-1941: … Kniga pamiati zhertv politicheskii repressii. (‘The Execution List: Moscow, 1937-1941: … Book of Remembrances of the victims of Political Repression’), (Moscow: Memorial Society, Zven’ia Publishing House, 2000), 229.

[23] L Sedov, ‘Why did Stalin Need this Trial?’, The Red Book on the Moscow Trials, http://www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/sedov/works/red/ch01.htm [4]

[24] . Ibid., ‘Domestic Political Reasons’.

[25] R Service, op. cit., 240-241.

[26] Ibid., 242.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Given that when Trotsky was empowered under Lenin he established or condoned the methods of jurisprudence, concentration camps, forced labour, and the ‘Red Terror’, that were later to be placed entirely at the feet of Stalin.

[30] Karl Marx, ‘Proletarians and Communists’, The Communist Manifesto, (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1975), 68.

[31] K R Bolton, ‘The State versus Parental Authority’, Journal of Social, Political & Economic Studies, Vol. 36, No. 2, Summer 2011, 197-217.

[32] K Marx, Communist Manifesto, op. cit.

[33] See Chapter V.

[34] L Sedov, op. cit., ‘Reasons of Foreign Policy’.

[35] L Trotsky, The Revolution Betrayed, Chapter 7, ‘Family, Youth and Culture’, http://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1936/revbet/ch07.htm

[36] K R Bolton, ‘The Psychopathology of the Left’, Ab Aeterno, No. 10, Jan,-March 2012, Academy of Social and Political Research (Athens), Paraparaumu, New Zealand. The discussion on Marx and on Trotsky show their pathological hatred of family.

[37] L Trotsky, The Revolution Betrayed, op. cit., ‘The Thermidor in the Family’.

[38] ‘There is no proletarian, not even a communist, movement that has not operated in the interests of money, in the directions indicated by money, and for the time permitted by money — and that without the idealist amongst its leaders having the slightest suspicion of the fact’. Oswald Spengler, The Decline of The West (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1971),Vol. II, 402.

[39] L Trotsky, op.cit.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Ibid.

[48] See below.

[49] A laudatory article on the ‘Dalton Plan’ states that the Dalton School was founded in New York in 1919 and was one of the most important progressive schools of the time, the Dalton Plan being adopted across the world, including in the USSR. It is described as ‘often chaotic and disorganized, but also intimate, caring, nurturing, and familial’. Interestingly it is described as a synthesis of the theories of John Dewey and Carleton Washburne. ‘Dalton School’, http://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/1902/Dalton-School.html [5]

Dewey along with the Trotsky apologist Sidney Hook (later avid Cold Warrior and winner of the American Medal of Freedom from President Ronald Reagan) organised the campaign to defend Trotsky at the time of the Moscow Purges of the late 1930s. See Chapter II below.

[50] A Zhandov, Speech at the discussion on music to the Central Committee of the Communist Party SU (Bolshevik), February 1948.

[51] Hewlett Johnson, The Socialist Sixth of the World (London: Victor Gollanncz, 1939), Book IV, ‘New Horizons’, http://www.marxists.org/archive/johnson-hewlett/socialistsixth/ch04.htm [6]

[52] R Overy, op. cit., 255-256.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Ibid., 257.

[55] Ibid., p. 258.

[56] Ibid., 352.

[57] Ibid., 353.

[58] Ibid.

[59] K R Bolton, Revolution from Above, op. cit., 134-143.

[60] Overy, op.cit., 361.

[61] Ibid., 366-367.

[62] Ibid., 366.

[63] Ibid., 371.

[64] Ibid., 376.

[65] T S Eliot, Notes Towards the Definition of Culture (London: Faber and Faber, 1967).

[66] Zhdanov, op. cit., 6.

[67] Encyclopaedia of Soviet Writers, http://www.sovlit.net/bios/proletkult.html [7]

[68] Zhdanov, op. cit., 6-7.

[69] Ibid., 7

[70] Ibid.

[71] The Big Five – a group of Russian composers during the 1860’s: Balakirev, Mussorgsky, Borodin, Rimsky-Korsakov, Cui.

[72] Zhdanov, op. cit., 7-8.

[73] Ibid., 12.

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2013/03/stalins-fight-against-international-communism/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: http://www.counter-currents.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/stalin-the-enduring-legacy.jpg

[2] Stalin: The Enduring Legacy: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1908476443/ref=as_li_ss_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=1908476443&linkCode=as2&tag=countercurren-20

[3] http://www.radtr.net/dergi/sayi6/bolton6.htm: http://www.radtr.net/dergi/sayi6/bolton6.htm

[4] http://www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/sedov/works/red/ch01.htm: http://www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/sedov/works/red/ch01.htm

[5] http://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/1902/Dalton-School.html: http://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/1902/Dalton-School.html

[6] http://www.marxists.org/archive/johnson-hewlett/socialistsixth/ch04.htm: http://www.marxists.org/archive/johnson-hewlett/socialistsixth/ch04.htm

[7] http://www.sovlit.net/bios/proletkult.html: http://www.sovlit.net/bios/proletkult.html

00:05 Publié dans Histoire, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : histoire, livre, staline, stalinisme, communisme, russie, urss, union soviétique, histoire, marxisme, années 20, années 30, idéologie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 07 novembre 2010

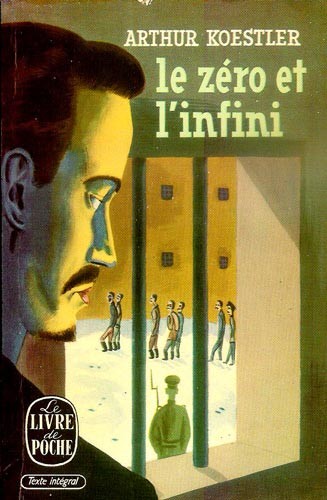

Réflexions sur "Le Zéro et l'Infini" d'Arthur Koestler

Michael WIESBERG :

Réflexions sur Le Zéro et l’Infini d’Arthur Koestler

La vie d’Arthur Koestler fut loin d’être paisible et monotone. Après avoir abandonné ses études d’ingénieur à la « Haute Ecole Technique » de Vienne, il a émigré vers la Palestine où il a vécu de petits boulots occasionnels. Après ses mésaventures palestiniennes, les éditions Ullstein de Berlin lui offrent un poste de correspondant au Proche Orient, à Paris, puis un poste de journaliste scientifique à Berlin même. Cela durera de 1926 à 1931. Cette période est caractérisée par l’engagement passionné de Koestler pour la cause sioniste. En 1931, il change d’option : il s’engage dans le parti communiste allemand. Pendant la guerre civile espagnole, il écope d’une condamnation à mort et échappe de peu à l’exécution. Pendant la seconde guerre mondiale, il sert brièvement dans les armées française et britannique. Il finit par s’établir à Londres, où il écrira des ouvrages de vulgarisation scientifique. Le 3 mars 1983, il se suicide.

La vie d’Arthur Koestler fut loin d’être paisible et monotone. Après avoir abandonné ses études d’ingénieur à la « Haute Ecole Technique » de Vienne, il a émigré vers la Palestine où il a vécu de petits boulots occasionnels. Après ses mésaventures palestiniennes, les éditions Ullstein de Berlin lui offrent un poste de correspondant au Proche Orient, à Paris, puis un poste de journaliste scientifique à Berlin même. Cela durera de 1926 à 1931. Cette période est caractérisée par l’engagement passionné de Koestler pour la cause sioniste. En 1931, il change d’option : il s’engage dans le parti communiste allemand. Pendant la guerre civile espagnole, il écope d’une condamnation à mort et échappe de peu à l’exécution. Pendant la seconde guerre mondiale, il sert brièvement dans les armées française et britannique. Il finit par s’établir à Londres, où il écrira des ouvrages de vulgarisation scientifique. Le 3 mars 1983, il se suicide.

Le roman Le Zéro et l’Infini de Koestler paraît d’abord à Londres en 1940. La figure centrale et fictive de ce roman est un bolchevique de la vieille garde, ancien commissaire du peuple : Roubachov. Il est accusé de « menées contre-révolutionnaires », après que les services secrets soviétiques, les sbires du NKVD, l’aient arrêté et placé en détention. D’après Koestler lui-même, cette figure de fiction est inspirée par les dirigeants bolcheviques réels, et de premier plan, que furent Karl Radek, Nicolas Boukharine et Léon Trotski, qui, tous, en ultime instance, devinrent des victimes des purges staliniennes de la seconde moitié des années 30. En créant le personnage de Roubachov, Koestler a essayé de montrer, de manière exemplative, ce qui se passait dans les prisons du NKVD et d’expliquer comment ce noyau dur des anciens révolutionnaires d’octobre 1917 a pu être liquidé. Roubachov est confronté à deux autres personnages, ses adversaires tout au long de l’intrigue : Ivanov et Gletkine. Ils représentent deux générations de bolcheviques. Ivanov, le plus âgé, reçoit l’ordre de convaincre Roubachov de la nécessité de faire des aveux. Bien sûr, Ivanov sait que les crimes imputés à Roubachov sont purement fictifs. Et, malgré cela, il tente de convaincre celui-ci qu’il serait insensé de jouer les martyrs. On ne doit pas transformer le monde en un « bordel sentimental et métaphysique ». La pitié, la conscience, le remord et le doute doivent demeurer des « dérapages répréhensibles ». On ne doit pas abjurer la violence tant qu’il y a du chaos dans le monde. Tout compromis avec sa propre conscience, explique Ivanov au prisonnier, équivaut à de la désertion. Comme l’histoire est a priori immorale, toute attitude qui reposerait sur des décisions morales dictées par la conscience d’un individu, équivaudrait à faire de la politique en s’inspirant des bonnes paroles d’un prêche dominical. Pour cette raison, explique Ivanov, les blessures que ressent Roubachov dans sa propre conscience, au vu des hommes sacrifiés au nom de la « raison de parti », ne sont jamais que des « fictions grammaticales ».

Pour Koestler, cette notion de « fiction grammaticale » doit nous expliquer cette part du moi que l’on ne définit pas comme « logique » mais comme « personnelle ». Or comme ce moi est inexistant pour le parti, mais que la grammaire réclame un substantif pour cette chose, Ivanov nomme cet aspect du « moi » celui de la « fiction grammaticale ». Roubachov, dans cette phase-là de sa détention, est tourmenté par des scrupules moraux, à cause de ses propres manières d’agir d’antan : celles-ci étaient déterminées exclusivement par un schéma de pensée rationnelle et acceptaient en toute conscience les pertes humaines qu’imposait cette rationalité. Ivanov réussit finalement à convaincre Roubachov que les idées, que celui-ci cultive et rumine, relèvent d’une « sentimentalité bourgeoise ». « On n’entendra aucun coq chanter », dit Ivanov, « si, objectivement parlant, des individus nuisibles sont liquidés ».

Pour Koestler, cette notion de « fiction grammaticale » doit nous expliquer cette part du moi que l’on ne définit pas comme « logique » mais comme « personnelle ». Or comme ce moi est inexistant pour le parti, mais que la grammaire réclame un substantif pour cette chose, Ivanov nomme cet aspect du « moi » celui de la « fiction grammaticale ». Roubachov, dans cette phase-là de sa détention, est tourmenté par des scrupules moraux, à cause de ses propres manières d’agir d’antan : celles-ci étaient déterminées exclusivement par un schéma de pensée rationnelle et acceptaient en toute conscience les pertes humaines qu’imposait cette rationalité. Ivanov réussit finalement à convaincre Roubachov que les idées, que celui-ci cultive et rumine, relèvent d’une « sentimentalité bourgeoise ». « On n’entendra aucun coq chanter », dit Ivanov, « si, objectivement parlant, des individus nuisibles sont liquidés ».

Ivanov conjure alors Roubachov de tirer les « conséquences logiques » de leurs conversations, et obtient du prisonnier que celui-ci se déclare prêt à signer un aveu qui va dans le sens de l’accusation. A partir de ce moment-là du récit, le roman prend une tournure dramatique. Ivanov, qui, lui aussi, est une figure controversée, est accusé d’avoir mené l’enquête sur Roubachov de manière trop négligente : il est alors remplacé par un représentant de la jeune génération de bolcheviques, qui ne connaît pas les compromis. Ivanov est ensuite liquidé.

Gletkine, qui prend la place d’Ivanov, représente, dans Le Zéro et l’Infini, une génération qui agit toujours sans réticence aucune selon la ligne fixée par le parti et qui ne connaît plus personnellement les circonstances vécues par les premiers bolcheviques dans la Russie des Tsars. La liste des crimes supposés que Gletkine présente à Roubachov, est en fait un ramassis d’accusations fantaisistes, dont, en tête, celle d’avoir fomenté un attentat contre le « numéro un », Staline. La volonté de résister, chez Roubachov, est ensuite annihilée par l’application d’une procédure d’audition véritablement éreintante. Au cours de cette longue audition, on apprend pour quels motifs Roubachov doit être sacrifié. « L’expérience nous apprend », explique Gletkine, « que l’on doit donner aux masses des explications simples et compréhensibles pour les processus difficiles et compliqués ». Si l’on disait aux paysans que malgré « les acquis de la révolution », ils sont restés fainéants et arriérés, on n’obtiendra rien. Mais si on leur explique qu’ils sont des « héros du travail » et que l’on attribue les maux qui les frappent encore à des saboteurs, alors on obtiendra quelque chose. Gletkine explique alors de manière fort plausible que le parti est régi par le principe que « la fin justifie les moyens ». Le parti attend donc des « vieux bolcheviques » qu’ils se sacrifient. La raison de cette exigence réside dans le fait que la guerre menace l’Union Soviétique. En cas de guerre, s’il y a des mouvements d’opposition, cela peut conduire à la catastrophe. Gletkine déclare alors à Roubachov qu’on lui reproche d’avoir, en liaison avec d’autres opposants, tenté de provoquer une scission au sein du parti. Si son repentir est « vrai », alors Roubachov doit aider le parti à éliminer cette scission. Il s’agit de montrer aux masses que tout opposant est un « criminel ». Après la victoire finale du socialisme, explique Gletkine, la vérité reviendra sans doute à la surface. A ce moment-là, Roubachov et les autres recevront la gratitude qui leur revient. Complètement brisé, Roubachov accepte pour finir de signer des aveux de culpabilité. Deux balles dans la nuque mettent fin à son existence.

Si l’on cherche à évaluer les conséquences des « grandes purges » pour l’Union Soviétique, l’attention se focalise immanquablement sur les successeurs des « vieux bolcheviques ». La nouvelle génération fut celle qui se soumit de manière inconditionnelle au parti. A la fin de la « tchistka » (de la « purge »), se dresse la pâle figure de l’apparatchik, caractérisée par une « non-identité ». Staline a créé les conditions préalables d’un système de parasites et de pleutres qui n’ânonnaient rien d’autre que les slogans doctrinaires du parti. Sous Staline, le matérialisme cru du marxisme-léninisme est entré dans un processus de perversion, dont l’apogée la plus emblématique fut l’émergence d’une pensée purement immanentiste, érigée au rang de dogme. C’est ainsi, in fine, que Staline a introduit les conditions initiales de l’effondrement final des systèmes sociaux du « socialisme réel » ou, plutôt, de l’égalitarisme radical. L’idée d’un ordre socialiste juste est resté une chimère en Europe orientale, pour laquelle des millions d’hommes ont dû sacrifier leur vie.

L’histoire ne se répète pas. Une tyrannie à la Hitler ou à la Staline ne se présentera plus. Mais il est certainement une chose que le livre de Koestler nous enseigne, et qui reste valable aujourd’hui : il nous montre où nous mène un monde régi par la pleutrerie et la pensée conformiste. Une république qui se vante d’incarner la liberté et la démocratie n’est pas pour autant immunisée contre les tumeurs totalitaires. Il faut donc toujours, dans tous les cas de figure, apprendre à se défendre contre la pleutrerie et le conformisme dès qu’ils se pointent à l’horizon.

Michael WIESBERG.

(article paru dans « Junge Freiheit », Berlin, n°11/1996, dans la série « Mein Lieblingsbuch / Folge 6 : « Sonnenfinsternis » von Arthur Koestler – Chronik der stalinistischen Säuberung » / « Mon livre favori / 6°partie : « Le Zéro et l’Infini » d’Arthur Koestler – Chronique des purges staliniennes » - Trad. franç. : octobre 2010).

00:10 Publié dans Littérature, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (2) | Tags : littérature, lettres, lettres anglaises, littérature anglaise, communisme, arthur koestler, anticommunisme, années 30, purges staliniennes, stalinisme, épuration |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook