mardi, 30 septembre 2025

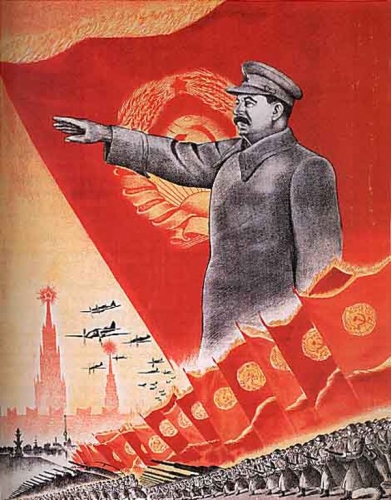

La question de Staline en Russie aujourd'hui - Empire, mythe et héritage du pouvoir soviétique

La question de Staline en Russie aujourd'hui

Empire, mythe et héritage du pouvoir soviétique

Alexander Douguine

Alexander Douguine retrace comment une figure, celle de Staline, est devenue, dans l’imaginaire russe, à la fois empereur, bourreau et légende.

L’immense popularité de Staline dans la Russie contemporaine est un phénomène complexe.

L’évaluation positive de Staline par la majorité du peuple est liée à plusieurs facteurs :

- Les succès évidents de l’URSS sous sa direction: essor économique, égalité matérielle, victoire dans la guerre, acquisitions territoriales et attitude ferme et impitoyable envers les élites dirigeantes (que le peuple a toujours détestées).

- La comparaison avec d’autres dirigeants de l’URSS — le chaos et la violence de la Révolution et de la guerre civile, où le romantisme héroïque s’était grandement estompé, rendant Lénine bien moins univoque; la propension à susciter des querelles et la bêtise chez Khrouchtchev; la stagnation et la sénile dégradation progressive de Brejnev. Sur ce fond, Staline apparaît éclatant. Un véritable Empereur.

- Le fait que Staline a été attaqué avec le plus de virulence par les libéraux de la perestroïka et des années 1990, libéraux qui étaient absolument répugnants aux yeux du peuple — ils étaient mesquins, russophobes et corrompus. Comparé à ces petits homoncules nuisibles qui n’ont fait que détruire, trahir, vendre et ridiculiser, Staline apparaissait comme divin. La bassesse de ces critiques libérales a contribué à élever la figure de Staline dans l'imaginaire du peuple.

Dans ce contexte, d’autres aspects de Staline ont été presque totalement oubliés: l’inhumaine cruauté de ses méthodes de prise et de conservation du pouvoir, un machiavélisme hypertrophié, la destruction effective de la paysannerie lors de l’industrialisation et de l’urbanisation, l’imposition d’une idéologie antichrétienne grossière et artificielle, les répressions contre les coupables comme contre les innocents, y compris les enfants, et bien d’autres choses encore.

La position des patriotes russes et de l’Église à l’égard de Staline a été divisée. Sous l’influence des points 1 à 3, et surtout à cause de la haine générale envers les libéraux, non seulement la gauche, mais aussi la droite et même les orthodoxes en sont venus à voir Staline d'un oeil favorable. Ce Staline impérial et mythique a complètement évincé la réalité.

Une minorité de patriotes et de membres de l’Église, cependant, a vu en Staline le bourreau du peuple russe et le persécuteur de l’orthodoxie. Mais précisément à cause de l’anti-stalinisme des libéraux, qui suscitent une répulsion insurmontable chez le peuple, cette position est devenue non seulement impopulaire, mais aussi dangereuse. Quiconque l’exprimait pouvait être accusé de libéralisme, ce qui est la pire des disqualifications pour un Russe — et à juste titre.

Aujourd’hui, le temps d’une évaluation plus équilibrée de Staline n’est toujours pas venu; des mythes idéologiques opposés restent à l’œuvre. Mais ce temps viendra nécessairement. De façon générale, l’histoire russe et notre peuple doivent évaluer sobrement et de façon responsable, dialectique et spirituelle, la période soviétique — ses significations, ses paradoxes, sa place dans la structure russe globale, ainsi que ses chefs et ses personnalités les plus marquantes.

L’obstacle évident à cela est la simple existence des libéraux. Tant qu’ils existent, toute perspective est biaisée et déformée, et aucune analyse sérieuse n’est possible. Ce n’est que lorsqu’ils auront entièrement disparu de notre société que les Russes, libérés de cette infection, pourront se demander: qu’était-ce donc tout cela? Un obscurcissement de la conscience, un effondrement ou une ascension?

Peut-être est-il temps de commencer à discuter de ce sujet non pas en public (en évitant la rhétorique et la polémique à tout prix), mais dans des cercles russes fermés ? Aujourd’hui, tout finit immédiatement sur les réseaux, dans un flux continu, dans le monde extérieur. Pourtant, les questions subtiles et non évidentes exigent une toute autre atmosphère.

Nous avons besoin de cercles russes fermés, de communautés organiques de gens de notre terre et de notre histoire. C’est en leur sein que les significations profondes peuvent être clarifiées. Les Russes doivent apprendre à écouter les Russes et à parler sur un tout autre ton. Trop longtemps, d’autres ont parlé en notre nom, déformant, consciemment ou non, les structures de notre pensée. Cela est devenu une habitude.

La cristallisation de la pensée requiert des conditions particulières. Viktor Kolesov montre que le mot russe dumat’ (« penser ») est formé de la racine um (« esprit ») et d’un préfixe généralisant très ancien d, qui s’est depuis longtemps fondu avec la racine. Ainsi, « penser » (dumat’) veut toujours dire penser ensemble, en cercle. On peut réfléchir (myslit’) seul, mais on ne peut penser (dumat’) qu’avec tous. D’où le nom même de Douma des boyards. Les boyards [l'aristocratie terrienne] se réunissent et pensent ensemble. C’est un cercle russe institutionnalisé.

15:36 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : alexandre douguine, staline, russie, actualité, histoire |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 30 octobre 2015

Diplomaţia lui Stalin

Diplomaţia lui Stalin

Ex: http://www.estica.eu

Istoria secolului nostru este învăţată din punctul de vedere american. La fel este şi în cazul celui de-al doilea Război Mondial, al Războiului Rece şi al Războiului din Golf. În optica americană, secolul XXI este “secolul american”, în care trebuie să se instaleze şi să se menţină o ordine mondială conform cu interesele americane, secol care este simultan “sfârşitul istoriei”, sfârşitul aventurii umane, sinteza definitivă a dialecticii istoriei. Francis Fukuyama, chiar înainte de războiul din Golf, afirma că odată cu căderea Cortinei de Fier şi sfârşitul “hegelianismului de stânga” pe care îl reprezenta URSS-ul, un singur model, cel al liberalismului american, va subzista secole de-a rândul. Cu condiţia ca niciun competitor să nu se zărească la orizont. De unde misiunea americană era aceea de a reacţiona rapid, mobilizând maximum de mijloace, contra oricărei veleităţi de a construi o ordine politică alternativă.

Cu câţiva ani înainte de Fukuyama, un autor germano-american, Theodore H. von Laue, pretindea că singura revoluţie veritabilă în lume şi în istorie era aceea a occidentalizării şi că toate revoluţiile politice non-occidentaliste, toate regimurile bazate pe alte principii decât cele în vogă în America, erau relicve ale trecutului, pe care numai nişte reacţionari perverşi le puteau adula, reacţionari pe care puterea americană, economică şi militară, urma să le măture rapid pentru a face loc unui hiper-liberalism de factură anglo-saxonă, debarasat de orice concurenţă.

Dacă hitlerismul este în mod general considerat ca o forţă reacţionară perversă faţă de care America a contribuit la eliminarea din Europa, se ştiu mai puţin motivele care l-au împins pe Truman şi pe protagoniştii atlantişti ai Războiului Rece să lupte contra stalinismului şi să facă din el un căpcăun ideologic, considerat explicit de către von Laue drept „reacţionar” în ciuda etichetei sale proprii de „progresist”. Această ambiguitate faţă de Stalin se explică prin alianţa americano-sovietică în timpul celui de-al Doilea Război mondial, când Stalin era supranumit în mod prietenos “Uncle Joe”. Cu toate acestea, de câţiva ani, numeroşi istorici revăd în mod inteligent poncifele pe care patruzeci şi cinci de ani de atlantism furibund le-au vehiculat în mass-media şi în cărţile noastre de istorie. Germanul Dirk Bavendamm a demonstrat în două lucrări meticuloase şi precise care au fost responsabilităţile lui Roosevelt în declanşarea conflictelor americano-japonez şi americano-german şi de asemenea care era duplicitatea preşedintelui american faţă de aliaţii săi ruşi. Valentin Falin, fostul ambasador al URSS-ului la Bonn, a publicat în Germania o lucrare de amintiri istorice şi de reflecţii istoriografice, în care acest briliant diplomat rus afirmă că Războiul Rece a început imediat după debarcarea anglo-americană din iunie 1944 pe plajele din Normandia: desfăşurându-şi armada lor navală şi aeriană, puterile occidentale duceau deja un război mai ales contra Uniunii Sovietice şi nu contra Germaniei muribunde.

O lectură atentă a mai multor lucrări recente consacrate multiplelor aspecte ale rezistenţei germane contra regimului hitlerist ne obligă să renunţăm definitiv la interpretarea istoriei celui de-al Doilea Război mondial şi a alianţei anglo-americano-sovietice după modelul convenţional. Ostilitatea faţă de Stalin după 1945 provine mai ales din faptul că Stalin înţelegea să practice o diplomaţie generală bazată pe relaţiile bilaterale între naţiuni, fără ca acestea să fie supervizate de o instanţă universală cum ar fi ONU. Apoi, după ce şi-a dat seama că cele două puteri anglo-saxone deciseseră singure la Casablanca să facă războiul excesiv cu Reich-ul, să declanşeze războiul total şi să ceară capitularea fără condiţii a Germaniei naţional-socialiste, Stalin s-a simţit exclus de aliaţii săi. Furios, el şi-a concentrat mânia în această frază bine ticluită, în aparenţă anodină, dar foarte semnificativă: „Hitlerii vin şi se duc, poporul şi statul german rămân”. Stalin nu considera naţional-socialismul hitlerist ca pe răul absolut sau chiar ca pe o esenţă netrecătoare, ci ca pe un accident al istoriei, o vicisitudine potrivnică Rusiei eterne, pe care armatele sovietice urmau pur şi simplu să caute s-o elimine. Dar, în logica diplomatică tradiţională, care îi aparţinea lui Stalin, în ciuda ideologiei mesianice marxiste, naţiunile nu pier: nu trebuie prin urmare să ceri o capitulare necondiţionată şi trebuie mereu să laşi poarta deschisă unor negocieri. În plin război, alianţele se pot schimba cu totul, aşa cum o arată clar istoria europeană. Stalin se mulţumeşte să ceară deschiderea unui al doilea front pentru a uşura misiunea armatelor sovietice şi a diminua pierderile de vieţi omeneşti în rândul ruşilor, dar acest front nu vine decât foarte târziu, ceea ce-i permite lui Valentin Falin să explice această întârziere ca pe primul act al Războiului Rece între puterile maritime anglo-saxone şi puterea continentală sovietică.

Această reticenţă a lui Stalin se explică şi prin contextul care a precedat imediat epilogul lungii bătălii de la Stalingrad şi debarcarea anglo-saxonă în Normandia. Când armatele lui Hitler şi ale aliaţilor săi slovaci, finlandezi, români şi unguri au intrat în URSS în 22 iunie 1941, sovieticii, oficial, au estimat că clauzele Pactului Molotov/Ribbentrop au fost trădate şi, în toamna lui 1942, după gigantica ofensivă victorioasă a armatelor germane în direcţia Caucazului, Moscova a fost constrânsă să sondeze adversarul său în vederea unei eventuale păci separate: Stalin dorea să se revină la termenii Pactului şi conta pe ajutorul japonezilor pentru a reconstitui, în masa continentală eurasiatică, acel „car cu patru cai” pe care i-l propusese Ribbentrop în septembrie 1940 (sau „Pactul Cvadripartit” între Reich, Italia, URSS şi Japonia). Stalin dorea o pace nulă: Wehrmacht-ul să se retragă dincolo de frontiera fixată de comun acord în 1939 şi URSS-ul să-şi panseze rănile. Mai mulţi agenţi au participat la aceste negocieri, ce au rămas în general secrete. Printre ei, Peter Kleist, ataşat în acelaşi timp de Cabinetul lui Ribbentrop şi de „Biroul Rosenberg”. Kleist, naţionalist german de tradiţie rusofilă în amintirea prieteniei dintre Prusia şi Ţari, va negocia la Stockholm, unde jocul diplomatic va fi strâns şi complex. În capitala suedeză, ruşii sunt deschişi la toate sugestiile; printre ei, ambasadoarea Kollontaï şi diplomatul Semionov. Kleist acţionează în numele Cabinetului Ribbentrop şi al Abwehr-ului lui Canaris (şi nu al „Biroului Rosenberg” care avea în vedere o balcanizare a URSS-ului şi crearea unui puternic stat ucrainean pentru a contrabalansa „Moscovia”). Al doilea protagonist al părţii germane a fost Edgar Klaus, un evreu din Riga care făcea legătura între sovietici şi Abwehr (el nu avea relaţii directe cu instanţele propriu-zis naţional socialiste).

În acest joc mai mult sau mai puţin triangular, sovieticii doreau revenirea la status-quo-ul de dinainte de 1939. Hitler a refuzat toate sugestiile lui Kleist şi a crezut că poate câştiga definitiv bătălia prin cucerirea Stalingradului, cheie a fluviului Volga, a Caucazului şi a Caspicii. Kleist, care ştia că o încetare a ostilităţilor cu Rusia ar fi permis Germaniei să rămână dominantă în Europa şi să-şi îndrepte toate forţele contra britanicilor şi americanilor, trece atunci de partea elementelor active ale rezistenţei anti-hitleriene, chiar dacă este personal dator instanţelor naţional-socialiste! Kleist îi contactează deci pe Adam von Trott zu Solz şi pe fostul ambasador al Reich-ului la Moscova, von der Schulenburg. El nu se adresează comuniştilor şi estimează, fără îndoială odată cu Canaris, că negocierile cu Stalin vor permite realizarea Europei lui Coudenhove-Kalergi (fără Anglia şi fără Rusia), pe care o visau de asemenea şi catolicii. Dar sovieticii nu se adresează nici ei aliaţilor lor teoretici şi privilegiaţi, comuniştii germani: ei pariază pe vechea gardă aristocratică, unde exista încă amintirea alianţei prusacilor şi ruşilor contra lui Napoleon, ca şi cea a neutralităţii tacite a germanilor în timpul Războiului Crimeii. Cum Hitler refuză orice negociere, Stalin, rezistenţa aristocratică, Abwehr-ul şi chiar o parte a gărzii sale pretoriene, SS-ul, decid că el trebuie să dispară. Aici trebuie văzută originea complotului care va duce la atentatul din 20 iulie 1944.

Dar după iarna lui 42-43, sovieticii au revenit la Stalingrad şi au distrus vârful de lance al Wehrmacht-ului, armata a şasea, care încercuia metropola de pe Volga. Partida germană a sovieticilor va fi atunci constituită de „Comitetul Germania Liberă”, cu mareşalul von Paulus şi cu ofiţeri ca von Seydlitz-Kurzbach, toţi prizonieri de război. Stalin nu avea în continuare încredere în comuniştii germani, din rândul cărora a eliminat ideologii nerealişti şi revoluţionarii maximalişti troţkişti, care au ignorat mereu deliberat, din orbire ideologică, noţiunea de „patrie” şi continuităţile istorice multiseculare; finalmente, dictatorul georgian nu l-a păstrat în rezervă, ca bun la toate, decât pe Pieck, un militant care nu şi-a pus niciodată prea multe întrebări. Pieck va face carieră în viitoarea RDG. Stalin nu visa nici un regim comunist pentru Germania post-hitleriană: el dorea o „ordine democratică forte”, cu o putere executivă mai marcată decât sub Republica de la Weimar. Această dorinţă politică a lui Stalin corespunde perfect alegerii sale iniţiale: pariul pe elitele militare, diplomatice şi politice conservatoare, provenind în majoritate din aristocraţie şi din Obrigkeitsstaat-ul[1] prusac. Democraţia germană, care trebuia să vină după Hitler, în opinia lui Stalin, urma să fie de ideologie conservatoare, cu o fluiditate democratică controlată, canalizată şi încadrată de un sistem de educaţie politică strictă.

Britanicii şi americanii au fost surprinşi: ei crezuseră că „Unchiul Joe” va înghiţi fără probleme politica lor maximalistă, ruptă total de uzanţele democratice în vigoare în Europa. Dar Stalin, ca şi Papa şi Bell, episcopul de Chichester, se opuneau principiului revoluţionar al predării necondiţionate pe care Churchill şi Roosevelt au vrut s-o impună Reich-ului (care va rămâne, cum gândea Stalin, în calitate de principiu politic în ciuda prezenţei efemere a unui Hitler). Dacă Roosevelt, făcând apel la dictatura mediatică pe care o controla bine în Statele Unite, a reuşit să-şi reducă adversarii la tăcere, indiferent de ideologie, Churchill a avut mai mari dificultăţi în Anglia. Principalul său adversar era acest Bell, episcop de Chichester. Pentru acesta din urmă, nu se punea problema de a reduce Germania la neant, căci Germania era patria lui Luther şi a protestantismului. Filosofiei predării necondiţionate a lui Churchill, Bell îi opunea noţiunea unei solidarităţi protestante şi-i punea în gardă pe omologii săi olandezi, danezi, norvegieni şi suedezi, ca şi pe interlocutorii săi din rezistenţa germană (Bonhoeffer, Schönfeld, von Moltke), pentru a face faţă belicismului exagerat al lui Churchill, care se exprima prin bombardarea masivă a obiectivelor civile, chiar şi în oraşe mici fără infrastructură industrială importantă. Pentru Bell, viitorul Germaniei nu era nici nazismul nici comunismul, ci o „ordine liberală şi democratică”. Această soluţie, preconizată de episcopul de Chichester, nu era evident acceptabilă de către naţionalismul german tradiţional: ea constituia o întoarcere subtilă la Kleinstaaterei, la mozaicul de state, principate şi ducate, pe care viziunile lui List, Wagner etc. şi pumnul lui Bismarck le şterseseră din centrul continentului nostru. „Ordinea democratică forte” sugerată de Stalin era mai acceptabilă pentru naţionaliştii germani, al căror obiectiv a fost mereu crearea unor instituţii şi a unei paidei puternice pentru a proteja poporul german, substanţa etnică germană, de propriile sale slăbiciuni politice, de lipsa simţului său de decizie, de particularismul său atavic şi de durerile sale morale incapacitante. Astăzi, evident, mulţi observatori naţionalişti constată că federalismul constituţiei din 1949 se înscrie poate destul de bine în tradiţia juridică constituţională germană, dar forma pe care a luat-o, în cursul istoriei RFG-ului, îi relevă natura sa de „concesie”. O concesie a puterilor anglo-saxone…

În faţa adversarilor capitulării necondiţionate din sânul coaliţiei antihitleriste, rezistenţa germană a rămas în ambiguitate: Beck şi von Hassel sunt pro-occidentali şi vor să urmeze cruciada anti-bolşevică, dar într-un sens creştin; Goerdeler şi von der Schulenburg sunt în favoarea unei păci separate cu Stalin. Claus von Stauffenberg, autorul atentatului din 20 iulie 1944 contra lui Hitler, provenea din cercurile poetico-ezoterice din München, unde poetul Stefan George juca un rol preponderent. Stauffenberg este un idealist, un „cavaler al Germaniei secrete”: el refuză să dialogheze cu „Comitetul Germania Liberă” al lui von Paulus şi von Seydlitz-Kurzbach: „nu putem avea încredere în proclamaţiile făcute din spatele sârmei ghimpate”.

Adepţii unei păci separate cu Stalin, adversari ai deschiderii unui front spre Est, au fost imediat atenţi la propunerile de pace sovietice emise de agenţii la post în Stockholm. Partizanii unei „partide nule” la Est sunt ideologic „anti-occidentali”, aparţinând cercurilor conservatoare rusofile (cum ar fi Juni-Klub sau acei Jungkonservativen din siajul lui Moeller van den Bruck), ligilor naţional-revoluţionare derivate din Wandervogel sau „naţionalismului soldăţesc”. Speranţa lor era de a vedea Wehrmacht-ul retrăgându-se în ordine din teritoriile cucerite în URSS şi de a se replia dincolo de linia de demarcaţie din octombrie 1939 în Polonia. În acest sens interpretează exegeţii contemporani ai operei lui Ernst Jünger faimosul său text de război intitulat „Note caucaziene”. Ernst Jünger percepe aici dificultăţile de a stabiliza un front în imensele stepe de dincolo de Don, unde gigantismul teritoriului interzice o reţea militară ermetică ca într-un peisaj central-european sau de tip picard-champenoise, muncit şi răsmuncit de generaţii şi generaţii de mici ţărani încăpăţânaţi care au ţesut teritoriul cu îngrădituri, proprietăţi, garduri şi construcţii de o rară densitate, permiţând armatelor să se prindă de teren, să se disimuleze sau să întindă ambuscade. Este foarte probabil ca Jünger să fi pledat pentru retragerea Wehrmacht-ului, sperând, în logica naţional-revoluţionară, care îi era proprie în anii 20 sau 30, şi unde rusofilia politico-diplomatică era foarte prezentă, ca forţele ruseşti şi germane, reconciliate, să interzică pentru totdeauna accesul în „Fortăreaţa Europa”, chiar în „Fortăreaţa Eurasia” puterilor talasocratice, care practică sistematic ceea ce Haushofer numea „politica anacondei”, pentru a sufoca orice veleitate de independenţă pe marginile litorale ale „Marelui Continent” (Europa, India, ţările arabe etc.).

Ernst Jünger redactează notele sale caucaziene în momentul în care Stalingradul cade şi armata a şasea este înecată în sânge, oroare şi zăpadă. Dar în ciuda victoriei de la Stalingrad, care le permite sovieticilor să bareze calea spre Caucaz şi Marea Caspică germanilor şi să impiedice orice manevră în amontele fluviului, Stalin urmează mai departe negocierile sale sperând în continuare să joace o „partidă nulă”. Sovieticii nu pun un termen demersurilor lor decât după întrevederile de la Teheran (28 noimebrie – 1 decembrie 1943). În acel moment, Jünger pare a se fi retras din rezistenţă. În celebrul său interviu din Spiegel din 1982, imediat după ce primise premiul Goethe la Frankfurt, el declara: „Atentatele întăresc regimurile pe care vor să le dărâme, mai ales dacă sunt ratate”. Jünger, fără îndoială ca şi Rommel, refuza logica atentatului. Ceea ce nu a fost cazul cu Claus von Stauffenberg. Deciziile luate de către aliaţii occidentali şi de către sovietici la Teheran au făcut imposibilă revenirea la punctul de pornire, adică la linia de demarcaţie din octombrie 1939 în Polonia. Sovieticii şi anglo-saxonii s-au pus de acord să „transporte dulapul polonez” spre Vest prin cedarea unei zone de ocupaţie permanentă în Silezia şi în Pomerania. În atari condiţii, naţionaliştii germani nu mai puteau negocia iar Stalin era din oficiu prins în logica maximalistă a lui Roosevelt, în vreme ce la început o refuzase. Poporul rus urma să plătească foarte scump această schimbare de politică, favorabilă americanilor.

După 1945, constatând că logica Războiului Rece vizează încercuirea şi izolarea Uniunii Sovietice pentru a o împiedica să ajungă la mările calde, Stalin a reiterat oferta sa Germaniei epuizate şi divizate: unificarea şi neutralitatea, adică libertatea de a-şi alege regimul politic după placul său, mai ales o „ordine democratică forte”. Acesta va fi obiectul „notelor lui Stalin” din 1952. Decesul prematur al Vojd-ului sovietic în 1953 nu a mai permis URSS-ului să continue să joace această carte germană. Hruşciov a denunţat stalinismul, a apăsat pe logica blocurilor pe care Stalin o refuzase şi nu a revenit la antiamericanism decât în momentul afacerii Berlinului (1961) şi a crizei din Cuba (1962). Nu se va mai vorbi despre „notele lui Stalin” decât înainte de perestroika, în timpul manifestaţiilor pacifiste din 1980-1983, când mai multe voci germane au reclamat afirmarea unei neutralităţi în afara oricărei logici de tip bloc. Unii emisari ai lui Gorbaciov vor mai vorbi despre acele note şi după 1985, mai ales germanistul Viatcheslav Dachitchev, care a luat cuvântul peste tot în Germania, chiar şi în câteva cercuri ultra-naţionaliste.

În lumina acestei noi istorii a rezistenţei germane şi a belicismului american, putem să înţelegem într-un mod diferit stalinismul şi anti-stalinismul. Acesta din urmă, de exemplu, serveşte la răspândirea unei mitologii politice false şi artificiale, al cărei obiectiv ultim este să respingă orice formă de concert internaţional bazat pe relaţiile bilaterale, să impună o logică a blocurilor sau o logică mondialistă prin intermediul acestui instrument rooseveltian care este ONU (Coreea, Congo, Irak: mereu fără Rusia!), să stigmatizeze din start orice raport bilateral între o putere medie europeană şi Rusia sovietică (Germania în 1952 şi Franţa lui De Gaulle după evenimentele din Algeria). Antistalinismul este o variantă a discursului mondialist. Diplomaţia stalinistă era, în felul ei şi într-un context foarte particular, păstrătoare a tradiţiilor diplomatice europene.

Bibliografie:

– Dirk BAVENDAMM, Roosevelts Weg zum Krieg. Amerikanische Politik 1914-1939, Herbig, München, 1983.

– Dirk BAVENDAMM, Roosevelts Krieg 1937-45 und das Rätsel von Pearl Harbour, Herbig, München, 1993.

– Valentin FALIN, Zweite Front. Die Interessenkonflikte in der Anti-Hitler-Koalition, Droemer-Knaur, München, 1995.

– Francis FUKUYAMA, La fin de l’histoire et le dernier homme, Flammarion, 1992.

– Klemens von KLEMPERER, German Resistance Against Hitler. The Search for Allies Abroad. 1938-1945, Oxford University Press/Clarendon Press, 1992-94.

– Theodore H. von LAUE, The World Revolution of Westernization. The Twentieth Century in Global Perspective, Oxford University Press, 1987.

– Jürgen SCHMÄDEKE/Peter STEINBACH (Hrsg.), Der Widerstand gegen den National-Sozialismus. Die deutsche Gesellschaft und der Widerstand gegen Hitler, Piper (SP n°1923), München, 1994.

Traducere: Vladimir Muscalu

Sursa: http://robertsteuckers.blogspot.ro/2011/12/normal-0-21-false-false-false_29.html

[1] Statul autoritar (n. tr.)

00:05 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : histoire, russie, urss, staline, diplomatie, politique internationale, allemagne, géopolitique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 30 mars 2013

Stalin’s Fight Against International Communism

Stalin’s Fight Against International Communism

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Editor’s Note:

This is the first chapter of Kerry Bolton’s new book Stalin: The Enduring Legacy [2] (London: Black House Publishing, 2012). The chapter is being reprinted as formatted in the book. Counter-Currents will also run a review of the book, which I highly recommend.

The notion that Stalin ‘fought communism’ at a glance seems bizarre. However, the contention is neither unique nor new. Early last century the seminal German conservative philosopher-historian Oswald Spengler stated that Communism in Russia would metamorphose into something distinctly Russian which would be quite different from the alien Marxist dogma that had been imposed upon it from outside. Spengler saw Russia as both a danger to Western Civilisation as the leader of a ‘coloured world-revolution’, and conversely as a potential ally of a revived Germany against the plutocracies. Spengler stated of Russia’s potential rejection of Marxism as an alien imposition from the decaying West that,

Race, language, popular customs, religion, in their present form… all or any of them can and will be fundamentally transformed. What we see today then is simply the new kind of life which a vast land has conceived and will presently bring forth. It is not definable in words, nor is its bearer aware of it. Those who attempt to define, establish, lay down a program, are confusing life with a phrase, as does the ruling Bolshevism, which is not sufficiently conscious of its own West-European, Rationalistic and cosmopolitan origin.[1]

Even as he wrote, Bolshevism in the USSR was being fundamentally transformed in the ways Spengler foresaw. The ‘rationalistic’ and ‘cosmopolitan’ origins of Bolshevism were soon being openly repudiated, and a new course was defined by Zhdanov and other Soviet eminences.

Contemporary with Spengler in Weimer Germany, there arose among the ‘Right’ the ‘National Bolshevik’ faction one of whose primary demands was that Germany align with the Soviet Union against the Western plutocracies. From the Soviet side, possibilities of an alliance with the ‘Right’ were far from discounted and high level Soviet sources cultivated contacts with the pro-Russian factions of the German Right including the National Bolsheviks.[2]

German-Soviet friendship societies included many conservatives. In Arbeitsgemeinschaft zum Studium der Sowjetrussichen Planwirtschaft (Arplan)[3] Conservative-Revolutionaries and National Bolsheviks comprised a third of the membership. Bund Geistige Berufe (BGB)[4] was founded in 1931 and was of particular interest to Soviet Russia, according to Soviet documents, which aimed ‘to attract into the orbit of our influence a range of highly placed intellectuals of rightist orientation’.[5]

The profound changes caused Konstantin Rodzaevsky, leader of the Russian Fascist Union among the White Russian émigrés at Harbin, to soberly reassess the USSR and in 1945 he wrote to Stalin:

Not all at once, but step by step we came to this conclusion. We decided that: Stalinism is exactly what we mistakenly called ‘Russian Fascism’. It is our Russian Fascism cleansed of extremes, illusions, and errors.[6]

In the aftermath of World War II many German war veterans, despite the devastating conflagration between Germany and the USSR, and the rampage of the Red Army across Germany with Allied contrivance, were vociferous opponents of any German alliance with the USA against the USSR. Major General Otto E Remer and the Socialist Reich Party were in the forefront of advocating a ‘neutralist’ line for Germany during the ‘Cold War’, while one of their political advisers, the American Spenglerian philosopher Francis Parker Yockey, saw Russian occupation as less culturally debilitating than the ‘spiritual syphilis’ of Hollywood and New York, and recommended the collaboration of European rightists and neo-Fascists with the USSR against the USA.[7] Others of the American Right, such as the Yockeyan and Spenglerian influenced newspaper Common Sense, saw the USSR from the time of Stalin as the primary power in confronting Marxism, and they regarded New York as the real ‘capitol’ of Marxism.[8]

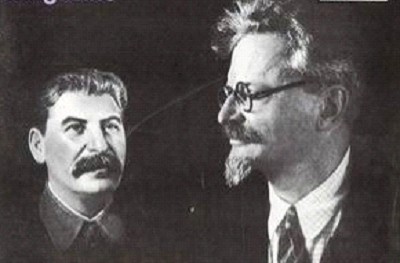

What might be regarded by many as an ‘eccentric’ element from the Right were not alone in seeing that the USSR had undergone a revolutionary transformation. Many of the Left regarded Stalin’s Russia as a travesty of Marxism. The most well-known and vehement was of course Leon Trotsky who condemned Stalin for having ‘betrayed the revolution’ and for reversing doctrinaire Marxism. On the other hand, the USA for decades supported Marxists, and especially Trotskyites, in trying to subvert the USSR during the Cold War. The USA, as the columnists at Common Sense continually insisted, was promoting Marxism, while Stalin was fighting it. This dichotomy between Russian National Bolshevism and US sponsored international Marxism was to having lasting consequences for the post-war world up to the present.

Stalin Purges Marxism

The Moscow Trials purging Trotskyites and other veteran Bolsheviks were merely the most obvious manifestations of Stalin’s struggle against alien Marxism. While much has been written condemning the trials as a modern day version of the Salem witch trials, and while the Soviet methods were often less than judicious the basic allegations against the Trotskyites et al were justified. The trials moreover, were open to the public, including western press, diplomats and jurists. There can be no serious doubt that Trotskyites in alliance with other old Bolsheviks such as Zinoviev and Kameneff were complicit in attempting to overthrow the Soviet state under Stalin. That was after all, the raison d’etre of Trotsky et al, and Trotsky’s hubris could not conceal his aims.[9]

The purging of these anti-Stalinist co-conspirators was only a part of the Stalinist fight against the Old Bolsheviks. Stalin’s relations with Lenin had not been cordial, Lenin accusing him of acting like a ‘Great Russian chauvinist’.[10] Indeed, the ‘Great Russians’ were heralded as the well-spring of Stalin’s Russia, and were elevated to master-race like status during and after the ‘Great Patriotic War’ against Germany. Lenin, near death, regarded Stalin’s demeanour as ‘offensive’, and as not showing automatic obedience. Lenin wished for Stalin to be removed as Bolshevik Party General Secretary.[11]

Dissolving the Comintern

The most symbolic acts of Stalin against International Communism were the elimination of the Association of Old Bolsheviks, and the destruction of the Communist International (Comintern). The Comintern, or Third International, was to be the basis of the world revolution, having been founded in 1919 in Moscow with 52 delegates from 25 countries.[12] Zinoviev headed the Comintern’s Executive Committee.[13] He was replaced by Bukharin in 1926.[14] Both Zinonviev and Bukharin were among the many ‘Old Bolsheviks’ eliminated by Stalin.

Stalin regarded the Comintern with animosity. It seemed to function more as an enemy agency than as a tool of Stalin, or at least that is how Stalin perceived the organisation. Robert Service states that Dimitrov, the head of the Comintern at the time of its dissolution, was accustomed to Stalin’s accusations against it. In 1937 Stalin had barked at him that ‘all of you in Comintern are hand in glove with the enemy’.[15] Dimitrov must have wondered how long he had to live.[16]

Instead of the Communist parties serving as agents of the world revolution, in typically Marxist manner, and the purpose for founding the Comintern, the Communist parties outside Russia were expected to be nationally oriented. In 1941 Stalin stated of this:

The International was created in Marx’s time in the expectation of an approaching international revolution. Comintern was created in Lenin’s time at an analogous moment. Today, national tasks emerge for each country as a supreme priority. Do not hold on tight to what was yesterday.[17]

This was a flagrant repudiation of Marxist orthodoxy, and places Stalinism within the context of National Bolshevism.

The German offensive postponed Stalin’s plans for the elimination of the Comintern, and those operatives who had survived the ‘Great Purge’ were ordered to Ufa, South of the Urals. Dimitrov was sent to Kuibyshev on the Volga. After the Battle of Stalingrad, Stalin returned to the issue of the Comintern, and told Dimitrov on 8 May 1943 to wind up the organisation. Dimitrov was transferred to the International Department of the Bolshevik Party Central Committee.[18] Robert Service suggests that this could have allayed fears among the Allies that Stalin would pursue world revolution in the post-war world. However, Stalin’s suspicion of the Comintern and the liquidation of many of its important operatives indicate fundamental belligerence between the two. In place of proletarian international solidarity, Stalin established an All-Slavic Committee[19] to promote Slavic folkish solidarity, although the inclusion of the Magyars[20] was problematic.

Stalin throughout his reign undertook a vigorous elimination of World Communist leaders. Stalin decimated communist refugees from fascism living in the USSR. While only 5 members of the Politburo of the German Communist Party had been killed under Hitler, in the USSR 7 were liquidated, and 41 out of 68 party leaders. The entire Central Committee of the Polish Communist Party in exile were liquidated, and an estimated 5000 party members were killed. The Polish Communist Party was formally dissolved in 1938. 700 Comintern headquarters staff were purged.[21]

Among the foreign Communist luminaries who were liquidated was Bela Kun, whose psychotic Communist regime in Hungary in 1919 lasted 133 days. Kun fled to the Soviet Union where he oversaw the killing of 50,000 soldiers and civilians attached to the White Army under Wrangle, who had surrendered after being promised amnesty. Kun was a member of the Executive Committee of the Comintern. A favourite of Lenin’s, this bloody lunatic served as a Comintern agent in Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia during the 1920s. In 1938 he was brought before a tribunal and after a brief trial was executed the same day.[22]

Another action of great symbolism was Stalin’s moves against the ‘Old Bolsheviks’, the veterans of the 1917 Revolution. Leon Sedov, Leon Trotsky’s son, in his pamphlet on the Great Purge of the late 1930s, waxed indignant that Stalin ‘coldly orders the shooting of Bolsheviks, former leaders of the Party and the Comintern, and heroes of the Civil War’.[23] ‘The Association of Old Bolsheviks and that of the former political prisoners has been dissolved. They were too strong a reminder of the “cursed” revolutionary past’.[24]

In place of the Comintern the Cominform was established in 1947, for the purpose of instructing Communist parties to campaign against the Marshall Aid programme that was designed to bring war-ravished Europe under US hegemony. ‘European communism was to be redirected’ towards maintaining the gains of the Red Army during World War II. ‘Communist parties in Western Europe could stir up trouble’, against the USA. The Cominform was far removed from being a resurrection of the old Comintern. As to who was invited to the inaugural meeting held at a secluded village in Poland, ‘Stalin… refused a request from Mao Zedong, who obviously thought that the plan was to re-establish the Communist International’. The Spanish and Portuguese parties were not invited, nor were the British, or the Greek Communist Party, which was fighting a civil war against the royalists.[25]

The extent of the ‘fraternity’ between the USSR and the foreign Communists can be gauged from the delegates having not been given prior knowledge of the agenda, and being ‘treated like detainees on arrival’. While Soviet delegates Malenkov and Zhdanov kept in regular communication with Stalin, none of the other delegates were permitted communication with the outside world.[26]

Repudiation of Marxist Doctrine

The implementation of Marxism as a policy upon which to construct a State was of course worthless, and Stalin reversed the doctrinaire Marxism that he had inherited from the Lenin regime. Leon Sedov indignantly stated of this:

In the most diverse areas, the heritage of the October revolution is being liquidated. Revolutionary internationalism gives way to the cult of the fatherland in the strictest sense. And the fatherland means, above all, the authorities. Ranks, decorations and titles have been reintroduced. The officer caste headed by the marshals has been reestablished. The old communist workers are pushed into the background; the working class is divided into different layers; the bureaucracy bases itself on the ‘non-party Bolshevik’, the Stakhanovist, that is, the workers’ aristocracy, on the foreman and, above all, on the specialist and the administrator. The old petit-bourgeois family is being reestablished and idealized in the most middle-class way; despite the general protestations, abortions are prohibited, which, given the difficult material conditions and the primitive state of culture and hygiene, means the enslavement of women, that is, the return to pre-October times. The decree of the October revolution concerning new schools has been annulled. School has been reformed on the model of tsarist Russia: uniforms have been reintroduced for the students, not only to shackle their independence, but also to facilitate their surveillance outside of school. Students are evaluated according to their marks for behaviour, and these favour the docile, servile student, not the lively and independent schoolboy. The fundamental virtue of youth today is the ‘respect for one’s elders’, along with the ‘respect for the uniform’. A whole institute of inspectors has been created to look after the behaviour and morality of the youth.[27]

This is what Leon Sedov, and his father, Leon Trotsky, called the ‘Bonapartist character of Stalinism’.[28] And that is precisely what Stalin represents in history: the Napoleon of the Bolshevik Revolution who reversed the Marxian doctrinal excrescences in a manner analogous to that of Napoleon’s reversal of Jacobin fanaticism after the 1789 French Revolution. Underneath the hypocritical moral outrage about Stalinist ‘repression’, etc.,[29] a number of salient factors emerge regarding Stalin’s repudiation of Marxist-Leninist dogma:

- The ‘fatherland’ or what was called again especially during World War II, ‘Holy Mother Russia’, replaced international class war and world revolution.

- Hierarchy in the military and elsewhere was re-established openly rather than under a hypocritical façade of soviet democracy and equality.

- A new technocratic elite was established, analogous to the principles of German ‘National Bolshevism’.

- The traditional family, the destruction of which is one of the primary aims of Marxism generally[30] and Trotskyism specifically,[31] was re-established.

- Abortion, the liberalisation of which was heralded as a great achievement in woman’s emancipation in the early days of Bolshevik Russia, was reversed.

- A Czarist type discipline was reintroduced to the schools; Leon Sedov condemned this as shackling the free spirit of youth, as if there were any such freedom under the Leninist regime.

- ‘Respect for elders’ was re-established, again anathema to the Marxists who seek the destruction of family life through the alienation of children from parents.[32]

What the Trotskyites and other Marxists object to was Stalin’s establishment the USSR as a powerful ‘nation-state’, and later as an imperial power, rather than as a citadel for world revolution. However, the Trotskyites, more than any other Marxist faction, allied themselves to American imperialism in their hatred of Stalinist Russia, and served as the most enthusiastic partisans of the Cold War.[33] Sedov continued:

Stalin not only bloodily breaks with Bolshevism, with all its traditions and its past, he is also trying to drag Bolshevism and the October revolution through the mud. And he is doing it in the interests of world and domestic reaction. The corpses of Zinoviev and Kamenev must show to the world bourgeoisie that Stalin has broken with the revolution, and must testify to his loyalty and ability to lead a nation-state. The corpses of the old Bolsheviks must prove to the world bourgeoisie that Stalin has in reality radically changed his politics, that the men who entered history as the leaders of revolutionary Bolshevism, the enemies of the bourgeoisie, – are his enemies also. Trotsky, whose name is inseparably linked with that of Lenin as the leader of the October revolution, Trotsky, the founder and leader of the Red Army; Zinoviev and Kamenev, the closest disciples of Lenin, one, president of the Comintern, the other, Lenin’s deputy and member of the Politburo; Smirnov, one of the oldest Bolsheviks, conqueror of Kolchak—today they are being shot and the bourgeoisie of the world must see in this the symbol of a new period. This is the end of the revolution, says Stalin. The world bourgeoisie can and must reckon with Stalin as a serious ally, as the head of a nation-state…. Stalin has abandoned long ago the course toward world revolution.[34]

As history shows, it was not Stalin to whom the ‘world bourgeoisie’ or more aptly, the world plutocracy, looked on as an ally, but leading Trotskyites whose hatred of Stalin and the USSR made them vociferous advocates of American foreign policy.

Family Life Restored

Leon Trotsky is particularly interesting in regard to what he saw as the ‘revolution betrayed’ in his condemnation of Stalinist policies on ‘youth, family, and culture’. Using the term ‘Thermidor’, taken from the French revolutionary era, in his description of Stalinism vis-à-vis the Bolshevik revolution, Trotsky began his critique on family, generational and gender relations. Chapter 7 of The Revolution Betrayed is worth reading in its entirety as an over-view of how Stalin reversed Marxism-Leninism. Whether that is ‘good’ or ‘bad’ is, of course, left to the subjectivity of the reader.[35]

The primary raison d’etre of Marxism for Trotsky personally seems to have been the destruction of religion and of family (as it was for Marx).[36] Hence, the amount of attention Trotsky gives to lamenting the return to traditional family relations under Stalin:

The revolution made a heroic effort to destroy the so-called ‘family hearth’ – that archaic, stuffy and stagnant institution in which the woman of the toiling classes performs galley labor from childhood to death. The place of the family as a shut-in petty enterprise was to be occupied, according to the plans, by a finished system of social care and accommodation: maternity houses, creches, kindergartens, schools, social dining rooms, social laundries, first-aid stations, hospitals, sanatoria, athletic organizations, moving-picture theaters, etc. The complete absorption of the housekeeping functions of the family by institutions of the socialist society, uniting all generations in solidarity and mutual aid, was to bring to woman, and thereby to the loving couple, a real liberation from the thousand-year-old fetters. Up to now this problem of problems has not been solved. The forty million Soviet families remain in their overwhelming majority nests of medievalism, female slavery and hysteria, daily humiliation of children, feminine and childish superstition. We must permit ourselves no illusions on this account. For that very reason, the consecutive changes in the approach to the problem of the family in the Soviet Union best of all characterize the actual nature of Soviet society and the evolution of its ruling stratum.[37]

Marxism, behind the façade of women’s emancipation, ridicules the traditional female role in the family as ‘galley labour’, but does so for the purpose of delivering women to the ‘galley labour’ of the Marxist state. The Marxist solution is to take the child from the parents and substitute parental authority for the State via childcare. As is apparent today, the Marxist ideal regarding the family and children is the same as that of big capitalism. It is typical of the manner by which Marxism, including Communism, converges with plutocracy, as Spengler pointed out soon after the 1917 Revolution in Russia.[38]

Trotsky states, ‘you cannot “abolish” the family; you have to replace it’. The aim was to replace the family with the state apparatus: ‘During the lean years, the workers wherever possible, and in part their families, ate in the factory and other social dining rooms, and this fact was officially regarded as a transition to a socialist form of life’. Trotsky decries the reversal by Stalin of this subversion of the family hearth: ‘The fact is that from the moment of the abolition of the food-card system in 1935, all the better placed workers began to return to the home dining table’. Women as mothers and wives were retuning to the home rather than being dragooned into factories, Trotsky getting increasingly vehement at these reversals of Marxism:

Back to the family hearth! But home cooking and the home washtub, which are now half shamefacedly celebrated by orators and journalists, mean the return of the workers’ wives to their pots and pans that is, to the old slavery.[39]

The original Bolshevik plan was for a new slavery where all would be bound to the factory floor regardless of gender, a now familiar aim of global capitalism, behind the façade of ‘equality’. Trotsky lamented that the rural family was even stronger: ‘The rural family, bound up not only with home industry but with agriculture, is infinitely more stable and conservative than that of the town’. There had been major reversals in the collectivisation of the peasant families: they were again obtaining most of their food from private lots rather than collectivised farms, and ‘there can no longer be any talk of social dining rooms’. ‘Thus the midget farms, [were] creating a new basis for the domestic hearthstone…’[40]

The pioneering of abortion rights by the Leninist regime was celebrated as a great achievement of Bolshevism, which was, however, reversed by Stalin with the celebration instead of motherhood. In terms that are today conventional throughout the Western world, Trotsky stated that due to the economic burden of children upon women,

…It is just for this reason that the revolutionary power gave women the right to abortion, which in conditions of want and family distress, whatever may be said upon this subject by the eunuchs and old maids of both sexes, is one of her most important civil, political and cultural rights. However, this right of women too, gloomy enough in itself, is under the existing social inequality being converted into a privilege.[41]

The Old Bolsheviks demanded abortion as a means of ‘emancipating women’ from children and family. One can hardly account for the Bolshevik attitude by an appeal to anyone’s ‘rights’ (sic). The answer to the economic hardship of childbearing was surely to eliminate the causes of the hardship. In fact, this was the aim of the Stalinists, Trotsky citing this in condemnation:

One of the members of the highest Soviet court, Soltz, a specialist on matrimonial questions, bases the forthcoming prohibition of abortion on the fact that in a socialist society where there are no unemployed, etc., etc., a woman has no right to decline ‘the joys of motherhood’.[42]

On June 27 1936 a law was passed prohibiting abortion, which Trotsky called the natural and logical fruit of a ‘Thermidorian reaction’.[43] The redemption of the family and motherhood was damned perhaps more vehemently by Trotsky than any other aspect of Stalinism as a repudiation of the ‘ABCs of Communism’, which he stated includes ‘getting women out of the clutches of the family’.

Everybody and everything is dragged into the new course: lawgiver and litterateur, court and militia, newspaper and schoolroom. When a naive and honest communist youth makes bold to write in his paper: ‘You would do better to occupy yourself with solving the problem how woman can get out of the clutches of the family’, he receives in answer a couple of good smacks and – is silent. The ABCs of Communism are declared a ‘leftist excess’. The stupid and stale prejudices of uncultured philistines are resurrected in the name of a new morale. And what is happening in daily life in all the nooks and corners of this measureless country? The press reflects only in a faint degree the depth of the Thermidorian reaction in the sphere of the family.[44]

A ‘new’ or what we might better call traditional ‘morale’ had returned. Marriage and family were being revived in contrast to the laws of early Bolshevik rule:

The lyric, academical and other ‘friends of the Soviet Union’ have eyes in order to see nothing. The marriage and family laws established by the October revolution, once the object of its legitimate pride, are being made over and mutilated by vast borrowings from the law treasuries of the bourgeois countries. And as though on purpose to stamp treachery with ridicule, the same arguments which were earlier advanced in favor of unconditional freedom of divorce and abortion – ‘the liberation of women’, ‘defense of the rights of personality’, ‘protection of motherhood’ – are repeated now in favor of their limitation and complete prohibition.[45]

Trotsky proudly stated that the Bolsheviks had sought to alienate children from their parents, but under Stalin parents resumed their responsibilities as the guardians of their children’s welfare, rather than the role being allotted to factory crèches. It seems, that in this respect at least, Stalinist Russia was less a Marxian-Bolshevik state than the present day capitalist states which insist that mothers should leave their children to the upbringing of crèches while they are forced to work; and ironically those most vocal in demanding such polices are often regarded as ‘right-wing’.

Trotsky lauded the policy of the early Bolshevik state, to the point where the state withdrew support from parents

While the hope still lived of concentrating the education of the new generations in the hands of the state, the government was not only unconcerned about supporting the authority of the ‘elders’, and, in particular of the mother and father, but on the contrary tried its best to separate the children from the family, in order thus to protect them from the traditions of a stagnant mode of life.[46]

Trotsky portrayed the early Bolshevik experiments as the saving of children from ‘drunken fathers or religious mothers’; ‘a shaking of parental authority to its very foundations’.[47]

Stalinist Russia also reversed the original Bolshevik education policy that had been based on ‘progressive’ American concepts and returned authority to the schools. In speaking of the campaign against decadence in music,[48] Andrei Zhdanov, Stalin’s cultural adviser, recalled the original Bolshevik education policy, and disparaged it as ‘very leftish’:

At one time, you remember, elementary and secondary schools went in for the ‘laboratory brigade’ method and the ‘Dalton plan’,[49] which reduced the role of the teacher in the schools to a minimum and gave each pupil the right to set the theme of classwork at the beginning of each lesson. On arriving in the classroom, the teacher would ask the pupils ‘What shall we study today?’ The pupils would reply: ‘Tell us about the Arctic’, ‘Tell us about the Antarctic’, ‘Tell us about Chapayev’, ‘Tell us about Dneprostroi’. The teacher had to follow the lead of these demands. This was called the ‘laboratory brigade method’, but actually it amounted to turning the organisation of schooling completely topsy-turvy. The pupils became the directing force, and the teacher followed their lead. Once we had ‘loose-leaf textbooks’, and the five point system of marks was abandoned. All these things were novelties, but I ask you, did these novelties stand for progress?

The Party cancelled all these ‘novelties’, as you know. Why? Because these ‘novelties’, in form very ‘leftish’, were in actual fact extremely reactionary and made for the nullification of the school.[50]

One observer visiting the USSR explained:

Theories of education were numerous. Every kind of educational system and experiment was tried—the Dalton Plan, the Project Method, the Brigade Laboratory and the like. Examinations were abolished and then reinstated; though with a vital difference. Examinations in the Soviet Union serve as a test for scholarship, not as a door to educational privilege.[51]

In particular the amorality inherent in Marxism was reversed under Stalinism. Richard Overy sates of this process:

Changing attitudes to behaviour and social environment under Stalin went hand-in-hand with a changing attitude towards the family… Unlike family policy in the 1920s, which assumed the gradual breakdown of the conventional family unit as the state supplied education and social support of the young, and men and women sought more collective modes of daily life, social policy under Stalin reinstated the family as the central social unit, and proper parental care as the model environment for the new Soviet generation. Family policy was driven by two primary motives: to expand the birth rate and to provide a more stable social context in a period of rapid social change. Mothers were respected as heroic socialist models in their own right and motherhood was defined as a socialist duty. In 1944 medals were introduced for women who had answered the call: Motherhood medal, Second Class for five children, First Class for six; medals of Motherhood Glory in three classes for seven, eight or nine offspring, for ten or more, mothers were justly nominated Heroine Mother of the Soviet Union, and an average of 5,000 a year won this highest accolade, and a diploma from the Soviet President himself.[52]

No longer were husband and wife disparaged as the ‘drunken father’ and the ‘religious mother’, from whom the child must be ‘emancipated’ and placed under state jurisdiction, as Trotsky and the other Old Bolshevik reprobates attempted. Professor Overy states, rather, that ‘the ideal family was defined in socialist-realist terms as large, harmonious and hardworking’. ‘Free love and sexual licence’, the moral nihilism encouraged by Bolshevism during its early phase, was being described in Pravda in 1936 as ‘altogether bourgeois’.[53]

In 1934 traditional marriage was reintroduced, and wedding rings, banned since the 1920s, were again produced. The austere and depressing atmosphere of the old Bolshevik marriage ceremony was replaced with more festive and prolonged celebration. Divorce, which the Bolsheviks had made easy, causing thousands of men to leave their families, was discouraged by raising fees. Absentee fathers were obliged to pay half their earnings for the upkeep of their families. Homosexuality, decriminalised in 1922, was recriminalised in 1934. Abortion, legalised in 1920, was outlawed in 1936, with abortionists liable to imprisonment from one to three years, while women seeking termination could be fined up to 300 roubles.[54] The exception was that those with hereditary illnesses could apply for abortion.[55]

Kulturkampf

The antithesis between Marxist orthodoxy and Stalinism is nowhere better seen than in the attitudes towards the family, as related above, and culture.

Andrei Zhdanov, the primary theoretician on culture in Stalinist Russia, was an inveterate opponent of ‘formalism’ and modernism in the arts. ‘Socialist-realism’, as Soviet culture was termed from 1932,[56] was formulated that year by Maxim Gorky, head of the Union of Soviet Writers.[57] It was heroic, folkish and organic. The individual artist was the conveyor of the folk-soul, in contrast to the art of Western decline, dismissively described in the USSR as ‘bourgeoisie formalism’.[58]

The original Bolshevik vision of a mass democratic art, organised as ‘Proletkult’, which recruited thousands of workers to be trained as artists and writers, as one would train workers to operate a factory conveyor built, was replaced by the genius of the individual expressing the soul of the people. While in The West the extreme Left and its wealthy patrons championed various forms of modernism,[59] in the USSR they were marginalized at best, resulting in the suicide for example of the Russian ‘Constructivist’ Mayakovsky. The revitalisation of Russian-Soviet art received its primary impetus in 1946 with the launching of Zhdanovschina.[60]

The classical composers from the Czarist era, such as Tchaikovsky, Glinka sand Borodin, were revived, after being sidelined in the early years of Bolshevism in favour of modernism, as were great non-Russian composers such as Beethoven, Brahms and Schubert.[61] Maxim Gorky continued to be celebrated as ‘the founder of Soviet literature and he continued to visit the USSR, despite his having moved to Fascist Italy. He returned to Russia in 1933.[62] Modernists who had been fêted in the early days of Bolshevism, such as the playwright, Nikolai Erdman, were relegated to irrelevance by the 1930s.[63]

Jazz and the associated types of dancing were condemned as bourgeoisie degeneracy.[64]

Zhdanov’s speech to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolshevik) intended primarily to lay the foundations of Soviet music, represents one of the most cogent recent attempts to define culture. Other than some sparse references to Marx, Lenin and internationalism, the Zhdanov speech should rank alongside T S Eliot’s Notes Towards A Definition of Culture[65] as a seminal conservative statement on culture. The Zhandov speech also helped set the foundation for the campaign against ‘rootless cosmopolitanism’ that was launched several years later. Zhdandov’s premises for a Soviet music were based on the classical and the organic connexion with the folk, striving for excellence, and expressing lofty values, rejecting modernism as detached from folk and tradition.

And, indeed, we are faced with a very acute, although outwardly concealed struggle between two trends in Soviet music. One trend represents the healthy, progressive principle in Soviet music, based upon recognition of the tremendous role of the classical heritage, and, in particular, the traditions of the Russian musical school, on the combination of lofty idea content in music, its truthfulness and realism, with profound, organic ties with the people and their music and songs – all this combined with a high degree of professional mastery. The other trend is that of formalism, which is alien to Soviet art, and is marked by rejection of the classical heritage under the guise of seeming novelty, by rejection of popular music, by rejection of service to the people in preference for catering to the highly individualistic emotions of a small group of select aesthetes.[66]

While some in the Proletkult, founded in 1917 were of Futurist orientation, declaring like the poet Vladimir Kirillov, for example, that ‘In the name of our tomorrow, we will burn Raphael, we will destroy museums, we will trample the flowers of art’, the Proletkult organisation was abolished in 1932,[67] and Soviet culture was re-established on classical foundations. Khdanov was to stress the classical heritage combined with the Russian folk traditions, as the basis for Soviet culture in his address:

Let us examine the question of attitude towards the classical heritage, for instance. Swear as the above-mentioned composers may that they stand with both feet on the soil of the classical heritage, there is nothing to prove that the adherents of the formalistic school are perpetuating and developing the traditions of classical music. Any listener will tell you that the work of the Soviet composers of the formalistic trend is totally unlike classical music. Classical music is characterised by its truthfulness and realism, by the ability to attain to unity of brilliant artistic form with profound content, to combine great mastery with simplicity and comprehensibility. Classical music in general, and Russian classical music in particular, are strangers to formalism and crude naturalism. They are marked by lofty idea content, based upon recognition of the musical art of the peoples as the wellspring of classical music, by profound respect and love for the people, their music and songs.[68]

Zhdanov’s analysis of modernism in music and his definition of classic culture is eminently relevant for the present state of Western cultural degeneracy:

What a step back from the highroad of musical development our formalists make when, undermining the bulwarks of real music, they compose false and ugly music, permeated with idealistic emotions, alien to the wide masses of people, and catering not to the millions of Soviet people, but to the few, to a score or more of chosen ones, to the ‘elite’! How this differs from Glinka, Chaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Dargomyjsky and Mussorgsky, who regarded the ability to express the spirit and character of the people in their works as the foundation of their artistic growth. Neglect of the demands of the people, their spirit and art means that the formalistic trend in music is definitely anti-popular in character.[69]

Zhdanov addressed a tendency in Russia that has thrived in The West: that of the ever new and the ‘theoretical’ that is supposedly so profound as to be beyond the understanding of all but depraved, pretentious or commodity-driven artistic coteries in claiming that only future generations will widely understand these artistic vanguards. However, Stalinist Russia repudiated the nonsense; and exposed the emperor as having no clothes:

It is simply a terrible thing if the ‘theory’ that ‘we will be understood fifty or a hundred years hence’, that ‘our contemporaries may not understand us, but posterity will’ is current among a certain section of Soviet composers. If this altitude has become habitual, it is a very dangerous habit.[70]

For Zhdanov, and consequently for the USSR, the classics were a folkish manifestation arising from the soul of the Russian people, rather than being dismissed in Marxian manner as merely products of bourgeoisie culture. In fact, as indicated previously, it was modernism that was regarded as a manifestation of ‘bourgeois decadence’. Zhandov castigated the modernists as elitist, aloof, or better said, alienated from the folk. On the other hand the great Russian classicists, despite their class origins, were upheld as paragons of the Russian folk culture:

Remember how the classics felt about the needs of the people. We have begun to forget in what striking language the composers of the Big Five,[71] and the great music critic Stasov, who was affiliated with them, spoke of the popular element in music. We have begun to forget Glinka’s wonderful words about the ties between the people and artists: “Music is created by the people and we artists only arrange it.” We are forgetting that the great master did not stand aloof from any genres if these genres helped to bring music closer to the wide masses of people. You, on the other hand, hold aloof even from such a genre as the opera; you regard the opera as secondary, opposing it to instrumental symphony music, to say nothing of the fact that you look down on song, choral and concert music, considering it a disgrace to stoop to it and satisfy the demands of the people. Yet Mussorgsky adapted the music of the Hopak, while Glinka used the Komarinsky for one of his finest compositions. Evidently, we shall have to admit that the landlord Glinka, the official Serov and the aristocrat Stasov were more democratic than you. This is paradoxical, but it is a fact. Solemn vows that you are all for popular music are not enough. If you are, why do you make so little use of folk melodies in your musical works? Why are the defects, which were criticised long ago by Serov, when he said that ‘learned’, that is, professional, music was developing parallel with and independently of folk music, repeating themselves? Can we really say that our instrumental symphony music is developing in close interaction with folk music – be it song, concert or choral music? No, we cannot say that. On the contrary, a gulf has unquestionably arisen here as the result of the underestimation of folk music by our symphony composers. Let me remind you of how Serov defined his attitude to folk music. I am referring to his article The Music of South Russian Songs in which he said: ‘Folk songs, as musical organisms, are by no means the work of individual musical talents, but the productions of a whole nation; their entire structure distinguishes them from the artificial music written in conscious imitation of previous examples, written as the products of definite schools, science, routine and reflexes. They are flowers that grow naturally in a given locale, that have appeared in the world of themselves and sprung to full beauty without the least thought of authorship or composition, and consequently, with little resemblance to the hothouse products of learned compositional activity’. That is why the naivete of creation, and that (as Gogol aptly expressed it in Dead Souls) lofty wisdom of simplicity which is the main charm and main secret of every artistic work are most strikingly manifest in them.[72]

It is notable that Zhdanov emphasised the basis of culture as an organic flowering from the nation. Of painting Zhandov again attacked the psychotic ‘leftist’ influences:

Or take this example. An Academy of Fine Arts was organised not so long ago. Painting is your sister, one of the muses. At one time, as you know, bourgeois influences were very strong in painting. They cropped up time and again under the most ‘leftist’ flags, giving themselves such tags as futurism, cubism, modernism; ‘stagnant academism’ was ‘overthrown’, and novelty proclaimed. This novelty expressed itself in insane carryings on, as for instance, when a girl was depicted with one head on forty legs, with one eye turned towards us, and the other towards Arzamas. How did all this end? In the complete crash of the ‘new trend’. The Party fully restored the significance of the classical heritage of Repin, Briullov, Vereshchagin, Vasnetsov and Surikov. Did we do right in reinstating the treasures of classical painting, and routing the liquidators of painting?[73]

The extended discussion here on Russian culture under Stalin is due to the importance that the culture-war between the USSR and the USA took, having repercussions that were not only world-wide but lasting.

Notes

[1] Oswald Spengler, The Hour of Decision (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1963), 61.

[2] K R Bolton, ‘Jünger and National-Bolshevism’ in Jünger: Thoughts & Perspectives Vol. XI (London: Black Front Press, 2012).

[3] Association for the Study of the Planned Economy of Soviet Russia.

[4] League of Professional Intellectuals.

[5] K R Bolton, ‘Jünger and National-Bolshevism’, op. cit.

[6] Cited by John J Stephan, The Russian Fascists (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1978), 338.

[7] K R Bolton, ‘Francis Parker Yockey: Stalin’s Fascist Advocate’, International Journal of Russian Studies, Issue No. 6, 2010, http://www.radtr.net/dergi/sayi6/bolton6.htm [3]

[8] K R Bolton, ‘Cold War Axis: Soviet Anti-Zionism and the American Right’’ see Appendix II below.

[9] See Chapter III: ‘The Moscow Trials in Historical Context’.

[10] R Service, Comrades: Communism: A World History (London: Pan MacMillan, 2008), 97.

[11] Ibid., 98.

[12] Ibid., 107.

[13] Ibid., 109.

[14] Ibid., 116.

[15] G Dimitrov, Dimitrov and Stalin 1934-1943: Letters from the Soviet Archives, 32, cited by R Service, ibid., 220.

[16] R Service, ibid., 220.

[17] G Dimitrov, op. cit., cited by Service, ibid., 221.

[18] R Service, ibid., 222.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Hungarians.

[21] Richard Overy, The Dictators: Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Russia (London: Allen Lane, 2004), 201.

[22] L I Shvetsova, et al. (eds.), Rasstrel’nye spiski: Moskva, 1937-1941: … Kniga pamiati zhertv politicheskii repressii. (‘The Execution List: Moscow, 1937-1941: … Book of Remembrances of the victims of Political Repression’), (Moscow: Memorial Society, Zven’ia Publishing House, 2000), 229.

[23] L Sedov, ‘Why did Stalin Need this Trial?’, The Red Book on the Moscow Trials, http://www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/sedov/works/red/ch01.htm [4]

[24] . Ibid., ‘Domestic Political Reasons’.

[25] R Service, op. cit., 240-241.

[26] Ibid., 242.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Given that when Trotsky was empowered under Lenin he established or condoned the methods of jurisprudence, concentration camps, forced labour, and the ‘Red Terror’, that were later to be placed entirely at the feet of Stalin.

[30] Karl Marx, ‘Proletarians and Communists’, The Communist Manifesto, (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1975), 68.

[31] K R Bolton, ‘The State versus Parental Authority’, Journal of Social, Political & Economic Studies, Vol. 36, No. 2, Summer 2011, 197-217.

[32] K Marx, Communist Manifesto, op. cit.

[33] See Chapter V.

[34] L Sedov, op. cit., ‘Reasons of Foreign Policy’.

[35] L Trotsky, The Revolution Betrayed, Chapter 7, ‘Family, Youth and Culture’, http://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1936/revbet/ch07.htm

[36] K R Bolton, ‘The Psychopathology of the Left’, Ab Aeterno, No. 10, Jan,-March 2012, Academy of Social and Political Research (Athens), Paraparaumu, New Zealand. The discussion on Marx and on Trotsky show their pathological hatred of family.

[37] L Trotsky, The Revolution Betrayed, op. cit., ‘The Thermidor in the Family’.

[38] ‘There is no proletarian, not even a communist, movement that has not operated in the interests of money, in the directions indicated by money, and for the time permitted by money — and that without the idealist amongst its leaders having the slightest suspicion of the fact’. Oswald Spengler, The Decline of The West (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1971),Vol. II, 402.

[39] L Trotsky, op.cit.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Ibid.

[48] See below.

[49] A laudatory article on the ‘Dalton Plan’ states that the Dalton School was founded in New York in 1919 and was one of the most important progressive schools of the time, the Dalton Plan being adopted across the world, including in the USSR. It is described as ‘often chaotic and disorganized, but also intimate, caring, nurturing, and familial’. Interestingly it is described as a synthesis of the theories of John Dewey and Carleton Washburne. ‘Dalton School’, http://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/1902/Dalton-School.html [5]

Dewey along with the Trotsky apologist Sidney Hook (later avid Cold Warrior and winner of the American Medal of Freedom from President Ronald Reagan) organised the campaign to defend Trotsky at the time of the Moscow Purges of the late 1930s. See Chapter II below.

[50] A Zhandov, Speech at the discussion on music to the Central Committee of the Communist Party SU (Bolshevik), February 1948.

[51] Hewlett Johnson, The Socialist Sixth of the World (London: Victor Gollanncz, 1939), Book IV, ‘New Horizons’, http://www.marxists.org/archive/johnson-hewlett/socialistsixth/ch04.htm [6]

[52] R Overy, op. cit., 255-256.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Ibid., 257.

[55] Ibid., p. 258.

[56] Ibid., 352.

[57] Ibid., 353.

[58] Ibid.

[59] K R Bolton, Revolution from Above, op. cit., 134-143.

[60] Overy, op.cit., 361.

[61] Ibid., 366-367.

[62] Ibid., 366.

[63] Ibid., 371.

[64] Ibid., 376.

[65] T S Eliot, Notes Towards the Definition of Culture (London: Faber and Faber, 1967).

[66] Zhdanov, op. cit., 6.

[67] Encyclopaedia of Soviet Writers, http://www.sovlit.net/bios/proletkult.html [7]

[68] Zhdanov, op. cit., 6-7.

[69] Ibid., 7

[70] Ibid.

[71] The Big Five – a group of Russian composers during the 1860’s: Balakirev, Mussorgsky, Borodin, Rimsky-Korsakov, Cui.

[72] Zhdanov, op. cit., 7-8.

[73] Ibid., 12.

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2013/03/stalins-fight-against-international-communism/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: http://www.counter-currents.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/stalin-the-enduring-legacy.jpg

[2] Stalin: The Enduring Legacy: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1908476443/ref=as_li_ss_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=1908476443&linkCode=as2&tag=countercurren-20

[3] http://www.radtr.net/dergi/sayi6/bolton6.htm: http://www.radtr.net/dergi/sayi6/bolton6.htm

[4] http://www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/sedov/works/red/ch01.htm: http://www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/sedov/works/red/ch01.htm

[5] http://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/1902/Dalton-School.html: http://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/1902/Dalton-School.html

[6] http://www.marxists.org/archive/johnson-hewlett/socialistsixth/ch04.htm: http://www.marxists.org/archive/johnson-hewlett/socialistsixth/ch04.htm

[7] http://www.sovlit.net/bios/proletkult.html: http://www.sovlit.net/bios/proletkult.html

00:05 Publié dans Histoire, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : histoire, livre, staline, stalinisme, communisme, russie, urss, union soviétique, histoire, marxisme, années 20, années 30, idéologie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 25 février 2013

The Historic Implications and Continuing Ramifications of the Trotsky-Stalin Conflict

Trotsky, Stalin, & the Cold War:

The Historic Implications & Continuing Ramifications of the Trotsky-Stalin Conflict

By Kerry Bolton

Ex; http://www.counter-currents.com/

Editor’s Note:

This is the second of two chapters on the Moscow Trials that we are reprinting from Kerry Bolton’s new book Stalin: The Enduring Legacy [2] (London: Black House Publishing, 2012). The chapters are reprinted as formatted in the book. Counter-Currents will also run a review of the book, which I highly recommend.

The Moscow Trials were symptomatic of a great divide that had occurred in Bolshevism. The alliance with Stalin during World War II had formed an assumption among US internationalists that after the Axis defeat a ‘new world order’ would emerge via the United Nations Organisation. This assumption was ill-founded, and the result was the Cold War. Trotskyists emerged as avid Cold Warriors dialectically concluding that the USSR represented the primary obstacle to world socialism. This essay examines the dialectical process by which major factions of Trotskyism became, in Stalinist parlance, a ‘tool of foreign powers and of world capitalism.’

One of the major accusations against Trotsky and alleged Trotskyists during the Moscow Trials of 1936-1938 was that they were agents of foreign capital and foreign powers, including intelligence agencies, and were engaged in sabotage against the Soviet State. In particular, with the advent of Nazi Germany in 1933, Stalin sought to show that in the event of war, which he regarded as inevitable, the Trotskyist network in the USSR would serve as a fifth column for Germany.

The background of these trials has been examined in Chapter III.

Stalin Correct in Fundamental Accusations Against Trotskyites What is significant is that Khrushchev did concede that Stalin was correct in his fundamental allegation that the Trotskyists, Bukharinites et al represented a faction that sought the ‘restoration of capitalism and capitulation to the world bourgeoisie’. However Khrushchev and even Stalin could not go far enough in their denunciation of Trotskyists et al as seeking to ‘restore capitalism’ and as being agents of foreign powers. To expose the full facts in regard to such accusations would also mean to expose some unpalatable, hidden factors of the Bolshevik Revolution itself, and of Lenin; which would undermine the whole edifice upon which Soviet authority rested – the October 1917 Revolution. Lenin, and Trotsky in particular, had intricate associations with many un-proletarian individuals and interests.

What is significant is that Khrushchev did concede that Stalin was correct in his fundamental allegation that the Trotskyists, Bukharinites et al represented a faction that sought the ‘restoration of capitalism and capitulation to the world bourgeoisie’. However Khrushchev and even Stalin could not go far enough in their denunciation of Trotskyists et al as seeking to ‘restore capitalism’ and as being agents of foreign powers. To expose the full facts in regard to such accusations would also mean to expose some unpalatable, hidden factors of the Bolshevik Revolution itself, and of Lenin; which would undermine the whole edifice upon which Soviet authority rested – the October 1917 Revolution. Lenin, and Trotsky in particular, had intricate associations with many un-proletarian individuals and interests.

The fact of behind the scenes machinations between the Bolsheviks and international finance was commented upon publicly by two very well-positioned but quite different sources: Henry Wickham Steed, conservative editor of The London Times, and Samuel Gompers, head of the American Federation of Labour.