Alexis de Tocqueville dut sa célébrité à son séjour aux États-Unis en 1831 – 1832 où il devait à l’origine étudier le système pénitentiaire local. À son corps défendant, Frédéric Pierucci s’est retrouvé pendant plus de deux ans au cœur du milieu carcéral étatsunien en ce début de XXIe siècle.

Ce patron monde de la division chaudière d’Alstom basé à Singapour est arrêté par le FBI dès l’arrivée de son avion de ligne à New York, le 14 avril 2013. Accusé de corruption d’élus indonésiens afin d’obtenir la construction d’une centrale électrique à Tarahan sur l’île de Sumatra, il pâtit du Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), une loi qui permet depuis 1977 aux autorités étatsuniennes et en particulier au ministère fédéral de la Justice – ou DOJ (Department of Justice) – de poursuivre n’importe qui n’importe où pour n’importe quoi. En 1998, le Congrès lui a conféré une valeur d’extraterritorialité. Cette loi dispose en outre des effets pernicieux du Patriot Act, de l’espionnage numérique généralisé orchestré par la NSA et encourage le FBI à placer au sein même des compagnies étrangères suspectées, souvent en concurrence féroce avec des firmes yankees, un mouchard infiltré prêt à tout balancer, puis une fois les entreprises condamnées, un « monitor », c’est-à-dire « un contrôleur qui rapporte au DOJ durant une période de trois ans (p. 80) ». Cette inacceptable ingérence résulte d’une conception hégémonique des activités économiques étatsuniennes. « Les autorités américaines considèrent que le moindre lien avec les États-Unis, cotation en bourse, échanges commerciaux en dollars, utilisation d’une boîte mail américaine, les autorise à agir (p. 77). » Le FCPA constitue donc une arme redoutable de la guerre économique et juridique que mène Washington au reste du monde. Par exemple, si le DOJ s’attaque aux sociétés pharmaceutiques, c’est parce qu’il considère les médecins étrangers comme des agents publics exerçant une délégation de service public !

Ce patron monde de la division chaudière d’Alstom basé à Singapour est arrêté par le FBI dès l’arrivée de son avion de ligne à New York, le 14 avril 2013. Accusé de corruption d’élus indonésiens afin d’obtenir la construction d’une centrale électrique à Tarahan sur l’île de Sumatra, il pâtit du Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), une loi qui permet depuis 1977 aux autorités étatsuniennes et en particulier au ministère fédéral de la Justice – ou DOJ (Department of Justice) – de poursuivre n’importe qui n’importe où pour n’importe quoi. En 1998, le Congrès lui a conféré une valeur d’extraterritorialité. Cette loi dispose en outre des effets pernicieux du Patriot Act, de l’espionnage numérique généralisé orchestré par la NSA et encourage le FBI à placer au sein même des compagnies étrangères suspectées, souvent en concurrence féroce avec des firmes yankees, un mouchard infiltré prêt à tout balancer, puis une fois les entreprises condamnées, un « monitor », c’est-à-dire « un contrôleur qui rapporte au DOJ durant une période de trois ans (p. 80) ». Cette inacceptable ingérence résulte d’une conception hégémonique des activités économiques étatsuniennes. « Les autorités américaines considèrent que le moindre lien avec les États-Unis, cotation en bourse, échanges commerciaux en dollars, utilisation d’une boîte mail américaine, les autorise à agir (p. 77). » Le FCPA constitue donc une arme redoutable de la guerre économique et juridique que mène Washington au reste du monde. Par exemple, si le DOJ s’attaque aux sociétés pharmaceutiques, c’est parce qu’il considère les médecins étrangers comme des agents publics exerçant une délégation de service public !

Ubu chez Kafka

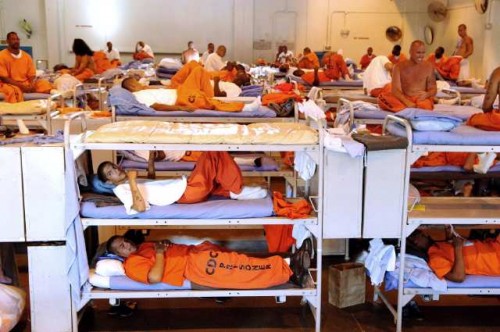

Le témoignage poignant de Frédéric Pierucci mériterait d’être lu par tous les auditeurs de l’École de guerre économique de Christian Harbulot tant il est passionnant et effrayant. Ce cadre supérieur presque quinquagénaire est conduit en détention provisoire dans la prison de Wyatt dans le Rhode Island classé niveau 4, soit de haute sécurité. Or il n’est « ni un récidiviste, ni un détenu dangereux. Ce choix est contraire à toute logique carcérale. Mais personne ne me fournira jamais la moindre explication (p. 40) ».

Ce qu’il découvre au cours de sa longue détention ne correspond jamais aux films, feuilletons et autres téléfilms réalisés par Hollywood pour décérébrer le monde entier. Prévues pour deux personnes, les cellules en accueillent quatre tant le taux d’emprisonnement aux États-Unis demeure le plus élevé au monde. Frédéric Pierucci nous aide à en comprendre les raisons profondes. On plonge ainsi dans les méandres ubuesques et kafkaïens de la justice étatsunienne au Connecticut. Pourquoi au fait cet État et non pas la Californie ou l’Indiana ? Peut-être parce que Frédéric Pierucci y vécut plusieurs années avant de s’installer en Asie… Les juges locaux y agissent en dociles caniches des procureurs fédéraux, d’exceptionnels salopards ceux-là ! Dès sa première confrontation avec l’un d’eux, David Novick, l’auteur trouve qu’il « ne fait aucun effort pour dissimuler son arrogance et me donne le sentiment d’être un bel arriviste (p. 21) ». Finalement jugé le 25 septembre 2017 en trente-huit minutes avec un seul bref échange avec le tribunal et condamné à trente mois de prison, une peine d’une sévérité exceptionnelle qui ne peut faire l’objet du moindre appel, Frédéric Pierucci dépeint bien la juge Janet Bond Arterton. « Cette magistrate incarne l’hypocrisie américaine dans toute sa splendeur (p. 332). »

Quant à ses avocats, ils respirent l’incompétence et la médiocrité. Le cabinet Day Pitney devrait les virer. La première, Liz, de trente-cinq – quarante ans, détonne immédiatement « par son manque d’expérience en matière pénale et son détachement qui fleurent l’amateurisme (p. 33) ». Le second, Stan, est un ancien procureur. D’abord rassuré, Frédéric Pierucci déchante bientôt; on a la franche impression que Stan aurait été brillant en avocat de la défense lors des procès de Moscou en 1938 ! La plupart des avocats « commencent leur carrière au sein des parquets, en tant que procureur adjoint, ou assistant, avant de rejoindre un grand cabinet. Dans leur immense majorité, ils ne plaideront jamais lors d’un procès pénal. Ce ne sont pas réellement des défenseurs, comme on l’entend en France, ce sont avant tout des négociateurs. Leur principal mission consiste à convaincre leur client d’accepter de plaider coupable. Et, ensuite, ils dealent la meilleure peine possible avec l’accusation (p. 116) ». Otage avéré du gouvernement étatsunien pour que General Electric acquiert à vil prix Alstom, un magnifique fleuron industriel français et européen et complètement ignoré par le gouvernement Hollande – Valls (deux tristes sires aux méfaits désormais légendaires), l’auteur apprend que « la justice américaine est un marché (p. 92) ». Un détenu de 57 ans qui cumule vingt-six ans de détention lui lance : « Ne fais jamais confiance à ton avocat. La plupart travaillent en sous-main pour le gouvernement. Et surtout, n’avoue jamais rien à ton conseil, autrement, il te forcera à faire un deal, à ses conditions, et si tu ne le fais pas, il balancera tout au procureur (p. 105). » Il se retrouve donc « sous surveillance, pris en étau entre Alstom et le DOJ, et sous contrôle d’un avocat que je n’ai pas choisi (p. 86) ». Dès leur première rencontre, Stan dépêché indirectement par Alstom avec qui il ne peut entrer en contact du fait de l’enquête exige de son client qu’il soit prêt à rembourser tous les frais en cas de condamnation, sinon il ne le défendra pas. Les rencontres suivantes avec « ses » avocats ressemblent plus à des discussions de marchands de tapis qu’à la préparation d’une défense. « Deal. Marché. Négociations ! Depuis que nous avons commencé notre briefing, Stan et Liz, ne me parlent que de négocier, jamais de juger sur des faits et des preuves (p. 90). »

Entraves multiples

Frédéric Pierucci note un trait psychologique révélateur qui réduit à néant l’illusion du Yankee self made man. « Les Américains adorent les process. Dans le cadre de leur travail, ils font rarement preuve d’imagination. En revanche, ils dépensent beaucoup d’énergie et de temps à respecter leurs process (p. 75). » Il profit du temps « offert » par son incarcération provisoire pour étudier le FCPA ainsi que le million et demi de pièces envoyées par les procureurs. En temps normal, cela nécessiterait au moins trois ans d’analyses et plusieurs millions de dollars de frais. Il en reçoit déjà environ trois mille enregistrées sur des CD. S’il peut « les visionner sur un écran et prendre des notes mais [… il n’a] pas le droit d’imprimer le moindre document (p. 141) », il ne peut consulter l’ordinateur qu’une heure par jour ! « Dans cette justice, les droits les plus élémentaires sont bafoués. Les représentants du Department of Justice ont parfaitement conscience que le temps joue pour eux. C’est donc à dessein qu’ils noient les accusés sous des tonnes de papier. Ils poursuivent toujours la même logique, implacable : priver les “ mis en examen ” – sauf les plus riches – des moyens réels de se défendre, pour les contraindre à plaider coupable (p. 142). »

Frédéric Pierucci

S’il a été placé dans un univers inconnu hostile où il est très vite accueilli par trois francophones, un Canadien, un Grec qui a étudié à Marseille, et Jacky, âgé de 75 ans, un ancien de la French Connection, que tous les prisonniers respectent, c’est parce que « pour parvenir à leur fin, les magistrats sont prêts à laisser mijoter leurs gibiers aussi longtemps que nécessaire. À Wyatt, certains prisonniers sont en attente de deal depuis deux, voire cinq ans (p. 114) ». Bien pire, « pour éviter de perdre une procédure, les procureurs américains sont aussi prêts à tous les arrangements. Ils incitent ainsi les inculpés à coopérer en balançant leurs complices. Même en l’absence de toutes preuves matérielles (p. 115) ». Ainsi les statistiques officielles vantent que « le DOJ a un taux de réussite en matière pénale digne de résultats d’élections sous Ceausescu : 98,5 % ! Cela veut dire que 98,5 % des personnes mises en examen par le DOJ sont au bout du compte reconnues coupables ! (p. 114) ».

Quiconque est allé aux États-Unis sait qu’il faut en permanence dépenser un pognon de dingue. Les mécanismes judiciaires n’échappent pas au dieu Dollar. « Dans les affaires financières, cela signifie souvent l’étude de dizaines ou de centaines de milliers de documents. Très rares sont donc les mis en examen qui peuvent (pendant plusieurs mois, voire des années) rémunérer (à hauteur de plusieurs centaines de milliers de dollars) un véritable défenseur, ou faire appel aux services d’un détective privé pour mener une contre-enquête (p. 113). »

L’enfer ultra-libéral

Le quotidien carcéral est lui aussi dominé par l’argent. « Wyatt est une prison privée. Le coût des repas est calculé au centime près. Il ne doit pas dépasser 1 dollar (0,80 euros). Et qui dit prison privée, dit entreprise, et donc bénéfices. Non seulement les détenus sont tenus de ne rien coûter à la collectivité mais ils sont priés de rapporter de l’argent aux sociétés qui gèrent les centres de détention (p. 65). » Pour téléphoner, « il faut d’abord payer ! Chaque détenu doit avoir un compte de cantine créditeur sur lequel est débité le coût, par ailleurs exorbitant, des communications téléphoniques (p. 56) ». Il n’y a pourtant que quatre vieux téléphones dans le réfectoire et les conversations enregistrées pour le FBI et les procureurs n’excèdent pas vingt minutes. Pour les appels vers l’étranger, « les personnes qui ont été autorisées à entrer en contact avec un détenu doivent s’inscrire sur une plateforme internet, à partir d’un compte bancaire ouvert aux États-Unis. Bonjour le cesse-tête pour un ressortissant étranger. En clair, cette procédure prend au bas mot une quinzaine de jours… et n’est pas donnée (p. 63) ». Si regarder la télévision est gratuite, l’écouter se paie !

Avant de se prononcer sur une éventuelle libération conditionnelle, le juge exige une caution élevée et que deux citoyens des États-Unis acceptent d’être conjoints et solidaires, c’est-à-dire qu’ils mettent en gage leurs propres maisons. Deux amis de Frédéric Pierucci, Linda et Michaël, le feront quand même, relevant l’image bien terni de la société étatsunienne. Après quinze mois de détention provisoire, Frédéric Pierucci peut rentrer en France : il a versé au préalable une caution de 200 000 dollars, ne doit pas voyager hors d’Europe et envoie chaque semaine un courriel à un officier de probation outre-Atlantique. L’auteur explique ces conditions draconiennes parce que « la justice américaine a eu, par le passé, toutes les difficultés pour saisir des biens (p. 89) » en France. Pour combien de temps encore ? Libre et en attente de son procès, l’auteur fonde une société de compliance et engage un procès aux prud’hommes contre Alstom à Versailles. Et voilà que le DOJ se mêle « d’une procédure civile opposant un salarié français, sous contrat français régi par le Code du travail français avec une société française et devant un tribunal français (p. 316) » !

Condamné à l’automne 2017, Frédéric Pierucci retourne aux États-Unis pour purger sa peine, incarcéré au Moshannon Valley Correction Center en plein centre de la Pennsylvanie. Les conditions de vie y sont plus rudes. « Le centre pénitentiaire est géré par GEO, un concessionnaire privé qui possède plusieurs établissements du même genre aux États-Unis et à l’étranger. Comme toute entreprise, GEO essaie de maximiser son profit. Le groupe n’hésite donc pas à rogner au maximum sur les services (repas, chauffage, maintenance des locaux, services médicaux), à augmenter le prix des articles que les détenus peuvent acheter à l’économat, ou à allonger au maximum la durée du “ séjour ”, en envoyant, par exemple, des prisonniers au mitard, pour leur faire perdre une partie de leur réduction de peine obtenue pour bonne conduite (pp. 341 – 342) » Les autorités françaises se manifestent enfin. Elles réclament son transfèrement. « L’administration pénitentiaire américaine aura épuisé tous les recours, afin que je sois transféré le plus tard possible (p. 368). » Pour preuve, « trois jours pour effectuer un trajet de moins de 400 kilomètres (p. 370) » ! Les services de l’immigration perdent bien sûr son passeport… Comme quoi, cela arrive encore à l’heure du numérique. L’administration du Moshannon Valley Correction Center n’apprécie pas les interventions de la France auprès du gouvernement fédéral. Souvent corrompus et au QI de limace obèse, les matons commencent à harceler l’auteur en lui privant de ses journaux français et des photographies des siens.

Esclavage légal

En quête de profits élevés, le Moshannon Valley Correction Center ne veut pas libérer le moindre détenu qui doit travailler entre une et cinq heures par jour. Grâce à Frédéric Pierucci, on apprend que l’esclavage se poursuit toujours aux États-Unis. « L’administration pénitentiaire s’appuie en effet sur le célèbre Treizième amendement de la constitution américaine abolissant l’esclavage “ sauf pour les prisonniers condamnés pour crime ”. Légalement, nous sommes donc tous des esclaves ! (p. 349). » Et après, ça ose jouer aux gendarmes du monde…

Enfin revenu définitivement en France, Frédéric Pierucci reste encore quelques jours en prison, mais dans de bien meilleures conditions, preuve supplémentaire que cet innocent n’a été qu’un simple lampiste. Il obtient finalement une liberté conditionnelle à l’automne 2018 de la part d’un juge d’application des peines.

Le Piège américain éclaire d’une lumière crue les dérives du droit anglo-saxon fort peu protecteur que le droit écrit romain et la démarche inquisitoriale. Cependant, « le système judiciaire américain, aussi inique qu’il soit, possède au moins un mérite : il est relativement transparent (p. 291) ». Le secret de l’instruction n’existe pas ! À l’aune du récit de Frédéric Pierucci, on ne peut que s’inquiéter d’un autre innocent, Julien Assange, détenu à Belmarsh, une prison britannique de haute sécurité, torturé psychologiquement, et poursuivi par le DOJ pour une supposée trahison. On comprend mieux aussi les mécanismes diaboliques de la CPI (Cour pénale internationale), des tribunaux spéciaux sur l’ex-Yougoslavie et le Ruanda et des jugements de 1945 – 1946 et de 1946 – 1948. Aveugle par nature, la Thémis anglo-saxonne se révèle toujours plus infecte et complètement débile.

Georges Feltin-Tracol

• Frédéric Pierucci (avec Matthieu Aron), Le piège américain. L’otage de la plus grande entreprise de déstabilisation économique témoigne, postface d’Alain Juillet, JC Lattès, 2019, 396 p., 22 €.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg