La littérature d’horreur dit-elle quelque chose du monde ? Un auteur qui ne s’intéresse ni à l’argent ni au sexe peut-il avoir un message radical sur ce qui lie l’économie à la reproduction ? En somme, Le Cauchemar d’Innsmouth de Howard Phillips Lovecraft a-t-il pour sujet la crise de 29 ?

Le Cauchemar d’Innsmouth est l’une des nouvelles les plus connues de Lovecraft. Elle figure parmi les titres réputés « canoniques » du « Mythe de Cthulhu » pour user d’un vocable qui appartient sans doute, désormais, à un état passé de la critique. En tout cas, nul, parmi les amateurs de Lovecraft, ne nie que ce texte soit l’un des plus importants d’une œuvre qui a marqué l’histoire de la littérature d’horreur. De même, la fécondité des images évoquées par ce récit est évidente aujourd’hui, que ce soit dans les romans, les bandes dessinées, les films.

Le schéma narratif est tout simple : un jeune homme est obligé de passer la nuit dans un village côtier de Nouvelle-Angleterre. L’activité halieutique, si prospère auparavant, semble désormais marginale. Les quais sont abandonnés, les maisons dans un état de décrépitude avancée, la population semble dégénérée. Après avoir rencontré un vieil homme qui lui dévoile les secrets d’Innsmouth, le narrateur réussit, non sans mal, à s’enfuir d’une ville dont la population lui est désormais hostile.

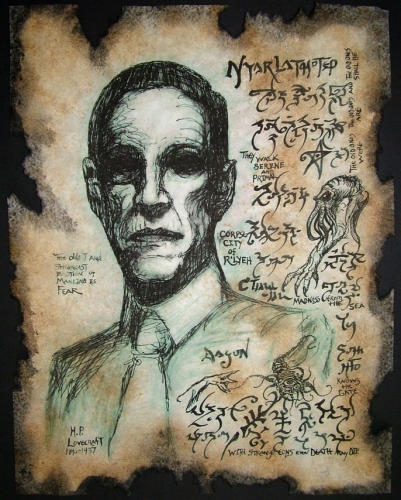

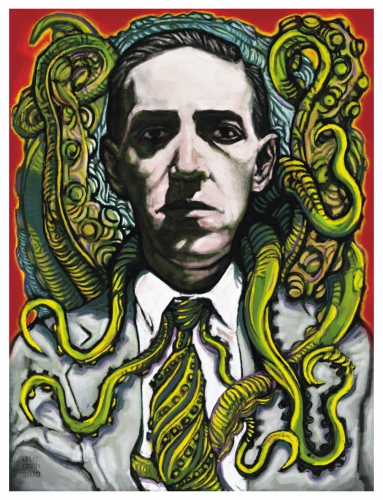

Ce récit a inspiré bien des réflexions et des analyses. La moins incontestable repose sur la plus choquante des révélations faites par Zadok Allen : Innsmouth a été le lieu de l’accouplement infâme de ses habitants avec des créatures venues des profondeurs des océans. Depuis, ces hybrides, déterminés par leur hérédité et leurs intérêts, conspirent à l’éradication de l’humanité. La logique de l’horreur dans ce récit tient donc au métissage. Or, comme la critique l’a justement fait remarquer, l’auteur lui-même, dans sa vision du monde et ses opinions politiques, était tout sauf indifférent à cette question. C’est parce que Lovecraft rejetait le métissage dans la vie réelle qu’il en a fait un objet d’horreur dans la fiction, voilà toute la thèse.

Lovecraft et l’argent

Il n’est nullement dans notre intention, ici, de nous écarter de cette interprétation dominante que nous croyons avoir par ailleurs renforcée, en faisant le parallèle avec les événements de Malaga Island que Lovecraft ne pouvait ignorer. Le métissage était pour Lovecraft un objet d’horreur sociale et littéraire. Il reste cependant à interroger les mécanismes qui rendent le métissage inéluctable et malheureux ; à révéler les ruses de l’abâtardissement et à démontrer en quoi le métissage est non seulement un ressort de l’horreur lovecraftienne mais ce qui en fait la spécificité et qui lui donne sa dimension cosmique.

En effet, s’arrêter à l’argument classique qui résume et explique tout par le racisme nous semble très insatisfaisant. Le racisme est une idée et les idées ne sont jamais premières dans l’ordre de la causalité. Le racisme est la conceptualisation, parfois pathologique, de la prise de conscience de la fragilité des liens biologiques et culturels qui lient l’homme à ses ancêtres, rien de plus. Rien de plus, mais rien de moins et la question de l’hérédité et de l’héritage, en somme, celle de Lovecraft comme héritier doit être posée.

Il est commun de noter que Lovecraft n’avait d’intérêt ni pour l’argent, ni pour le sexe. Or, son œuvre, de par la question de la filiation, partout présente, met le sexe en avant. Non pas le sexe comme idée théorisant le plaisir — sous les formes jumelles de l’amour ou de la perversion — mais le sexe comme réalité biologique dont le plaisir n’est qu’une ruse, c’est-à-dire le mécanisme de transmission des caractères héréditaires. Qu’en est-il, alors, de l’argent ? N’est-il pas, lui aussi, chose qui s’hérite ?

Le mépris notoire de Lovecraft pour tout ce qui est vénal ne fait pas de lui un homme qui méprise l’argent. C’est un luxe que la gêne lui refuse. Cet homme incapable (délibérément incapable) d’exiger ce qui lui est dû, n’est en rien un inconscient. L’éthique n’est pas chez lui l’alibi de la faiblesse. Ce gentleman généreux et magnanime sait vivre chichement, voilà tout. Il sait épargner aux autres ses propres fragilités, fussent-elles innocentes. Tout au long de sa vie, il s’est montré économe. Il mangeait peu et mal ; il n’achetait pas tous les livres qu’il désirait ; il ne voyageait que quand il le pouvait et toujours par les moyens les plus modestes.

Robert Olmstead, le héros du Cauchemar d’Innsmouth, parcourt la Nouvelle-Angleterre en « amateur d’antiquité et de généalogie » en « choisissant toujours le trajet le plus économique ». Le personnage et son auteur ont en commun de voyager pour les mêmes raisons et avec les mêmes contraintes. C’est l’obligation de ne pas trop dépenser qui amène le protagoniste de ce théâtre de l’horreur à prendre le misérable bus d’Innsmouth et c’est sa curiosité pour les antiquités et la généalogie qui le pousse à quitter son « île de placide ignorance. » En effet, les personnages de Lovecraft, comme Lovecraft lui-même, ne sont animés ni par la libido sentiendi (le sexe), ni par la libido dominandi (le pouvoir que seul donne l’argent dans les sociétés modernes), mais par la libido sciendi, (la volonté de savoir). Robert Olmstead ne déroge pas à la règle : il veut tout savoir sur le monde et il finira par tout savoir de lui-même, y compris le pire.

Le cauchemar de 1929

Cependant, l’argent et, plus largement, la question économique ne sont pas un simple ressort de l’intrigue. Ils en sont le cœur. Le tableau qui est fait d’Innsmouth est tout de contraste. Aux couleurs chatoyantes de l’opulence passée s’opposent celles, délavées, de la décrépitude présente. « Il reste plus de maisons vides que de gens », mais ce sont les belles et dignes maisons de l’aristocratie commerçante qui sont, aujourd’hui, délabrées. De même, les vastes entrepôts de briques rouges le long des quais sont à l’abandon. Quant à l’église et à la salle de réunion maçonnique, on y rend un autre culte désormais. Lovecraft, lecteur de Spengler, décrit là une parfaite pseudomorphose : les structures minérales sont toujours là, mais ceux qui les peuplent et, de ce fait, leur nature elle-même, sont radicalement altérés.

Jadis le commerce, la pêche et les conserveries de poisson avaient enrichi Innsmouth. Aujourd’hui, sans que rien ne le justifie, la ville n’est plus que l’ombre d’elle-même. L’angoisse première naît de cette ruine inexplicable. Cependant, l’affinerie Marsh, elle, semble encore en activité. N’est-ce point paradoxal alors qu’il n’y a plus ni commerce ni navires au long cours pour ramener des métaux précieux ? En tout cas, ce noyau d’activité au sein d’une ville rongée et ruinée ne paraît en rien freiner le déclin général. À croire que les bénéfices, s’il y en a, ne profitent à personne…

Quand Lovecraft écrit Le Cauchemar d’Innsmouth, l’Amérique est au début de la Grande Dépression. Pour beaucoup d’Américains, le Krach de 1929 a été une surprise totale et les événements qui ont suivi sont apparus comme dépourvus de toute logique. Les rares esprits assez lucides pour en comprendre la rationalité y ont vu la conséquence nécessaire de l’excès de crédit. Il y a eu un pacte trompeur entre l’espoir et le prêt. L’espoir a déçu, le prêt s’est réduit à la dette et les hommes ne furent plus rien qu’esclaves de la dette. Voilà ce que disaient certains contemporains. Mais, n’est-ce point de cela qu’il s’agit dans la nouvelle de Lovecraft ?

Que dit le vieux Zadok Allen à Robert Olmstead ? Que les plus riches et les plus aventureux des voyageurs et des commerçants d’Innsmouth ont conclu, dans les îles des mers du Sud, un marché avec une race amphibie très ancienne. La situation économique n’était pas bonne au lendemain de la guerre de 1812. Que demandaient-ils, au fond, ces hommes aux visages de poisson, en échange de leur or ? Qu’on expédie quelques Canaques à la mer pour qu’ils les offrent à leurs dieux ? La belle affaire ! Ce n’est pas cher payé ! Et pour le reliquat, il serait toujours temps de voir.

Per usura n’ont les hommes de lignées pures

Mais les créatures venues de la mer avaient bien plus à vendre que leur or. Elles voulaient autre chose et étaient prêtes à donner bien plus en contrepartie. Que vos fils et nos filles s’accouplent et leur progéniture sera immortelle, dirent-elles ! Passant leurs réticences premières, non sans déchirement, non sans violence, les habitants d’Innsmouth l’acceptèrent. C’est une façon trop tentante de régler ses dettes que de les reporter sur la génération suivante et puis doit-elle se plaindre ? Elle ne sera plus humaine, certes, elle sera, par ses épousailles, éternellement liée à Dagon et à jamais tributaire de forces par nature hostiles à l’Homme puisqu’en concurrence avec lui dans le struggle for life cosmique, mais elle sera, aussi, à tout jamais libérée de la finitude humaine.

Alors, « les gens ont commencé a pus rien faire », à quoi bon ? L’or venait de la mer et achetait les complaisances ; le poisson abondait et permettait de nourrir des hommes désormais à demi-poisson ; le temps n’était plus à craindre ; l’attente n’aboutissait plus à la mort ; la vie n’était qu’un lent glissement vers le fond des océans et vers une autre façon de vivre, de rire, de tuer. Tout au plus fallait-il prêter l’oreille à la musique des abysses dans l’impatience du retour de Celui qui n’est pas mort. Car, le païen Lovecraft fait d’Innsmouth le lieu d’une attente messianique, celle d’un grand nettoyage, suivi du remplacement de la race humaine par une autre à la fois plus ancienne et plus radicalement tournée vers ce futur qui verra le retour des Grands Anciens.

Cependant, le lecteur sait depuis le début que cette échéance eschatologique sera reculée. Le narrateur échappe à la ville et dénonce ce qui s’y passe à un gouvernement qui n’hésite pas à renoncer un instant à être un État de droit en recourant à l’état d’exception.

Ce que Lovecraft décrit dans sa nouvelle, il le voit sous ses yeux. L’Italie et l’Allemagne en Europe, les États-Unis du New Deal sous ses yeux lui montrent que la crise de 1929 et, au-delà du symptôme, que la modernité ne sont pas inéluctables. Comme chez beaucoup de conservateurs, l’espérance dans l’État (dans sa violence) se substitue au pessimisme politique. Le socialisme comme organisation de l’économie apparaît, aux yeux de ces hommes, comme un moyen de préservation de l’ordre ancien — non dans sa lettre, mais dans son esprit.

Le cauchemar d’Innsmouth est celui de la dette et de son corollaire, l’abâtardissement. Seul le réveil de l’État peut nous en sauver (provisoirement), y est-il suggéré. Comment ? Par l’état d’exception, par la déportation, par l’extermination. Le massacre final n’est rien d’autre que la vision fantasmagorique d’un New Deal musclé, d’un fascisme à l’américaine. L’horreur romanesque ou politique n’a d’autre issue, pour Lovecraft, que dans cette ultime violence retardatrice et seulement retardatrice. Car le gentleman de Providence sait aussi cette profonde vérité : tout passe.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

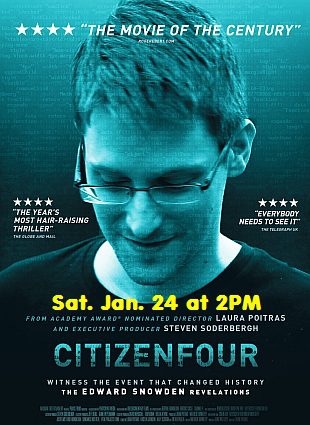

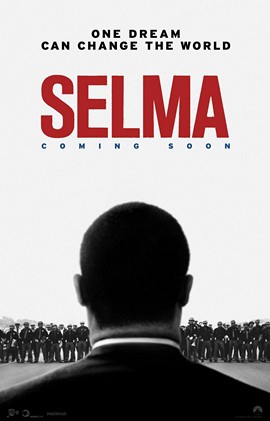

Selma will be mentioned in the history books but will not get the attention it really deserves for the relevance it should have for a new generation of youth. There will be no mention in the history books regarding the importance of Edward Snowden because his story not only instructs a larger public but indicts the myth of American democracy. Yet, American Sniper resembles a familiar narrative of false heroism and state violence for which thousands of pages will be written as part of history texts that will provide the pedagogical context for imposing on young people a mode of hyper-masculinity built on the false notion that violence is a sacred value and that war is an honorable ideal and the ultimate test of what it means to be a man. The stories a society tells about itself are a measure of how it values itself, the ideals of democracy, and its future.

Selma will be mentioned in the history books but will not get the attention it really deserves for the relevance it should have for a new generation of youth. There will be no mention in the history books regarding the importance of Edward Snowden because his story not only instructs a larger public but indicts the myth of American democracy. Yet, American Sniper resembles a familiar narrative of false heroism and state violence for which thousands of pages will be written as part of history texts that will provide the pedagogical context for imposing on young people a mode of hyper-masculinity built on the false notion that violence is a sacred value and that war is an honorable ideal and the ultimate test of what it means to be a man. The stories a society tells about itself are a measure of how it values itself, the ideals of democracy, and its future.

“La battaglia rientra nelle grandi passioni. [...] E’ un canto antico e tremendo, che risale all’alba dell’uomo: nessuno avrebbe mai pensato che fosse ancora così vivo in noi”. In questo scritto di guerra non manca nulla: il sangue, l’orrore, la trincea, l’eros, il coraggio, il fuoco, la paura… Questo per dare un’idea di ciò che aspetta il lettore che abbia il coraggio e la maturità di affrontare quest’opera rovente, che di certo non poteva non piacere ad un giovane nazional-socialista dei tempi. Perché Jünger è stato considerato, e forse è considerato ancora, un nazista. E’ vero che Hitler disse “Jünger non si tocca!” e lo protesse per ben due volte dalle grinfie di Göring che voleva la sua testa. Ma furono il rispetto per il soldato e lo scrittore di guerra che, con tutta probabilità, spinsero il Führer a perdonare a Jünger il suo comportamento. Ci si riferisce al suo antinazismo allegorico, aleggiante nel romanzo Sulle scogliere di marmo, e alla sua parte nella congiura capitanata da Stauffenberg che sfumò nel fallito attentato a Hitler, ben narrato nel film di Bryan Singer Operazione Valchiria. Scrisse un romanzo antinazista e partecipò all’attentato a Hitler, che mirava ad ucciderlo. Anche se in lui l’idea dell’uccisione del tiranno era indicice di mentalità rozza. Queste due cose stanno ben a sottolineare il fantomatico nazismo di cui fu accusato. Ma agli occhi stanchi e superficiali dei molti faciloni, è apparso così per molto tempo. È vero invece che i nazisti trassero, a piene mani, buona parte della loro cultura da alcuni scritti del grande soldato tedesco. Solo in seguito al premio Goethe, ottenuto nell’82, venne riabilitato ufficialmente come scrittore.

“La battaglia rientra nelle grandi passioni. [...] E’ un canto antico e tremendo, che risale all’alba dell’uomo: nessuno avrebbe mai pensato che fosse ancora così vivo in noi”. In questo scritto di guerra non manca nulla: il sangue, l’orrore, la trincea, l’eros, il coraggio, il fuoco, la paura… Questo per dare un’idea di ciò che aspetta il lettore che abbia il coraggio e la maturità di affrontare quest’opera rovente, che di certo non poteva non piacere ad un giovane nazional-socialista dei tempi. Perché Jünger è stato considerato, e forse è considerato ancora, un nazista. E’ vero che Hitler disse “Jünger non si tocca!” e lo protesse per ben due volte dalle grinfie di Göring che voleva la sua testa. Ma furono il rispetto per il soldato e lo scrittore di guerra che, con tutta probabilità, spinsero il Führer a perdonare a Jünger il suo comportamento. Ci si riferisce al suo antinazismo allegorico, aleggiante nel romanzo Sulle scogliere di marmo, e alla sua parte nella congiura capitanata da Stauffenberg che sfumò nel fallito attentato a Hitler, ben narrato nel film di Bryan Singer Operazione Valchiria. Scrisse un romanzo antinazista e partecipò all’attentato a Hitler, che mirava ad ucciderlo. Anche se in lui l’idea dell’uccisione del tiranno era indicice di mentalità rozza. Queste due cose stanno ben a sottolineare il fantomatico nazismo di cui fu accusato. Ma agli occhi stanchi e superficiali dei molti faciloni, è apparso così per molto tempo. È vero invece che i nazisti trassero, a piene mani, buona parte della loro cultura da alcuni scritti del grande soldato tedesco. Solo in seguito al premio Goethe, ottenuto nell’82, venne riabilitato ufficialmente come scrittore.

Recall how Obama had declined up to the last minute to order Mubarak to step down, and how Vice President Joe Biden had pointedly declined to describe Mubarak as a dictator. Only when millions rallied against the regime did Obama shift gears, praise the youth of Egypt for their inspiring mass movement, and withdraw support for the dictatorship. After that Obama pontificated that Ali Saleh in Yemen (a key ally of the U.S. since 2001) had to step down in deference to protesters. Saleh complied, turning power to another U.S. lackey (who has since resigned). Obama also declared that Assad in Syria had “lost legitimacy,” commanded him to step down, and began funding the “moderate” armed opposition in Syria. (The latter have at this point mostly disappeared or joined al-Qaeda and its spin-offs. Some have turned coat and created the “Loyalists’ Army” backing Assad versus the Islamist crazies.)

Recall how Obama had declined up to the last minute to order Mubarak to step down, and how Vice President Joe Biden had pointedly declined to describe Mubarak as a dictator. Only when millions rallied against the regime did Obama shift gears, praise the youth of Egypt for their inspiring mass movement, and withdraw support for the dictatorship. After that Obama pontificated that Ali Saleh in Yemen (a key ally of the U.S. since 2001) had to step down in deference to protesters. Saleh complied, turning power to another U.S. lackey (who has since resigned). Obama also declared that Assad in Syria had “lost legitimacy,” commanded him to step down, and began funding the “moderate” armed opposition in Syria. (The latter have at this point mostly disappeared or joined al-Qaeda and its spin-offs. Some have turned coat and created the “Loyalists’ Army” backing Assad versus the Islamist crazies.) *As New York senator Clinton endorsed the murderous ongoing sanctions against Iraq, imposed by the UN in 1990 and continued until 2003. Initially applied to force Iraqi forces out of Kuwait, the sanctions were sustained at U.S. insistence (and over the protests of other Security Council members) up to and even beyond the U.S. invasion in 2003. Bill Clinton demanded their continuance, insisting that Saddam Hussein’s (non-existent) secret WMD programs justified them. In 1996, three years into the Clinton presidency, Albright was asked whether the death of half a million Iraq children as a result of the sanctions was justified, and famously replied in a television interview, “We think it was worth it.” Surely Hillary agreed with her friend and predecessor as the first woman secretary of state. She also endorsed the 1998 “Operation Desert Fox” (based on lies, most notably the charge that Iraq had expelled UN inspectors) designed to further destroy Iraq’s military infrastructure and make future attacks even easier.

*As New York senator Clinton endorsed the murderous ongoing sanctions against Iraq, imposed by the UN in 1990 and continued until 2003. Initially applied to force Iraqi forces out of Kuwait, the sanctions were sustained at U.S. insistence (and over the protests of other Security Council members) up to and even beyond the U.S. invasion in 2003. Bill Clinton demanded their continuance, insisting that Saddam Hussein’s (non-existent) secret WMD programs justified them. In 1996, three years into the Clinton presidency, Albright was asked whether the death of half a million Iraq children as a result of the sanctions was justified, and famously replied in a television interview, “We think it was worth it.” Surely Hillary agreed with her friend and predecessor as the first woman secretary of state. She also endorsed the 1998 “Operation Desert Fox” (based on lies, most notably the charge that Iraq had expelled UN inspectors) designed to further destroy Iraq’s military infrastructure and make future attacks even easier. What can those who revere her point to in this record that in any way betters the planet or this country? Clinton’s record of her tenure in the State Department is entitled Hard Choices, but it has never been hard for Hillary to choose brute force in the service of U.S. imperialism and its controlling 1%.

What can those who revere her point to in this record that in any way betters the planet or this country? Clinton’s record of her tenure in the State Department is entitled Hard Choices, but it has never been hard for Hillary to choose brute force in the service of U.S. imperialism and its controlling 1%.