Graham Harman

Graham Harman

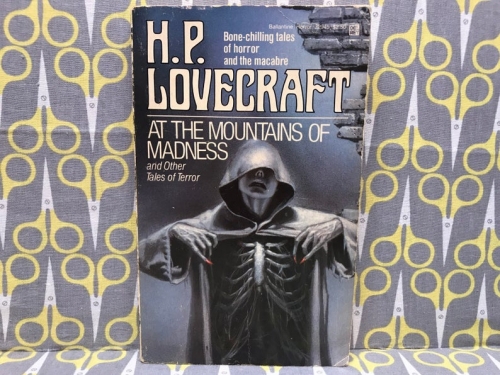

Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy [2]

Winchester, UK: Zero Books, 2012

A winter storm in NYC is less the Currier and Ives experience of upstate and more like several days of cold slush, more suggestive—and we’ll see that suggestiveness will be a very key term—of Dostoyevsky than Dickens.

On a purely personal level, such weather conditions I privately associate[1] with my time—as in “doing time”—at the small Canadian college (fictionalized by fellow inmate Joyce Carol Oates as “Hilberry College”[2]) where a succession of more or less self-pitying exiles from the mainstream—from Wyndham Lewis and Marshall McLuhan to the aforementioned Oates—suffered the academic purgatory of trying to teach, or even interest, the least-achieving students in Canada in such matters as Neoplatonism and archetypal psychology.[3]

One trudged to ancient, wooden classrooms and consumed endless packs of powerful Canadian cigarettes, washed down with endless cups of rancid vending machine coffee. No Starbucks for us, and no whining about second-hand smoke. We were real he-men back then! There was one student, a co-ed of course, who did complain, and the solution imposed was to exile her—exile within exile!—to a chair in the hallway, like a Spanish nun allowed to listen in from behind a grill.

Speaking of Spain, one of the damned souls making his rounds was a little, goateed Marrano from New York, via Toronto’s Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, no less, who was now attempting to explain Husserl and Heidegger, to “unpack” with his tiny hands what he once called, with an incredulous shake of the head, “that incredible language of his,” to his sullen and ungrateful students.[4]

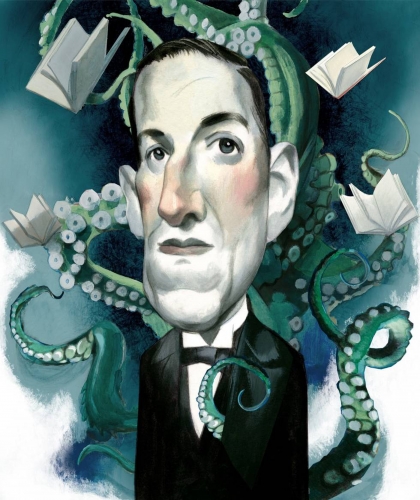

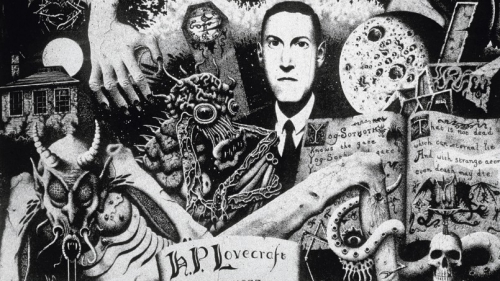

I thought of this academic Homunculus, who played Naphta to another’s Schleppfuss[5] in my intellectual upbringing, when this book made its appearance in my e-mail box one recent, snowing—or slushy—weekend. For Harman wants to explain Husserl and Heidegger as well, or rather, his own take on them, which I gather he and a bunch of colleagues have expanded into their own field of Object Oriented Ontology (OOO) or Speculative Realism. And to do so, he has appropriated the work of H. P. Lovecraft, suggesting that Lovecraft play the same role of philosophical exemplar in his philosophy, as Hölderlin does in Heidegger’s [3].

“That incredible language of his” indeed!

Part One tries to explain this Object Oriented business, but only after he tries to justify or excuse dealing with someone still often regarded as a glorified pulp hack on the same level with the great Hölderlin. He tries to short-circuit the attacks of highbrow critics, still exemplified by Edmund Wilson’s, by denouncing their rhetorical strategy of paraphrase.

Paraphrase? What’s wrong with that? Perfectly innocent, what? Well, no. Drawing on Slavoj Žižek’s notion of the “stupidity of content”—the equal plausibility of any proverb, say, and its opposite—Harman insists that nothing can be paraphrased into something else—reality is not itself a sentence, and so it is “is too real to be translated without remainder into sentences” (p. 16, my italics). Language can only allude to reality.

What remains left over, resistant to paraphrase, is the background or context that gave the statement its meaning.[6] Paraphrase, far from harmless or obvious, is packed with metaphysical baggage—such as the assumption that reality itself is just like a sentence—that enables the skilled dialectician to reduce anything to nonsensical drivel.

Harman gives many, mostly hilarious, examples of “great” literature reduced to mere “pulp” through getting the Wilson treatment. (Perhaps too many—the book does tend to bog down from time to time as Harman indulges in his real talent for giving a half dozen or so increasing “stupid” paraphrases of passages of “great” literature.)[7]

Genre or “pulp” writing is itself the epitome of taking the background for granted and just fiddling with the content, and deserves Edmund Wilson’s famous condemnation of both its horror and mystery genres. But Lovecraft, contra Wilson, is quite conscious, and bitingly critical, of the background conditions of pulp—both in his famous essays on horror and, unmentioned by Harman, his voluminous correspondence and ghost-writing—and thus ideally equipped to manipulate it for higher, or at least more interesting, purposes.

The pulp writer takes the context for granted (the genre “conventions”) and concentrates on content—sending someone to a new planet, putting a woman in charge of a space ship, etc.[8] If Lovecraft did this, or only this, he would indeed be worthy of Wilson’s periphrastic contempt. But Lovecraft is interested in doing something else: “No other writer is so perplexed by the gap between objects and the power of language to describe them, or between objects and the qualities they possess” (p.3, my italics).

Since philosophy is the science of the background, Lovecraft himself is to this extent himself a philosopher, and useful to Harman as more than just a source of fancy illustrations: “Lovecraft, when viewed as a writer of gaps between objects and their qualities, is of great relevance for my model of object oriented ontology” (p. 4).

Back, then to Harman’s philosophy or his “ontography” as he calls it. I call it Kantianism, but I’m a simple man. The world presents us with objects, both real (Harman is no idealist) and sensuous (objects of thought, say), which bear various properties, both real (weight, for example) and sensuous (color, for example). Thus, we have real and sensuous objects, as well as the real and sensuous qualities that belong to them . . . usually.

All philosophers, Harman suggests, have been concerned with one or another of the gaps that occur when the ordinary relations between these four items fail. Some philosophers promote or delight in some gap or other, while others work to deny or explain it away. Plato introduced a gap between ordinary objects and their more real essences, while Hume delighted in denying such a gap and reducing them to agglomerations of sensual qualities.

Harman, in explicitly Kantian fashion this time, derives four possible failures (Kant would call them antinomies). Gaps can occur between a real object and its sensuous qualities, a real object and its real qualities, a sensuous object and its sensuous qualities, and a sensuous object and its real qualities. Or, for simplicity, RO/SQ, RO/RQ, SQ/SO, and SO/RQ.

Take SQ/SO. This gap, where the object’s sensuous qualities, though listed, Cubist-like, ad nauseam, fail, contra Hume, to suggest any kind of objective unity, even of a phenomenal kind—the object is withdrawn from us, as Heidegger would say. It occurs in a passage such as the description of the Antarctic city of the Elder Race:

The effect was that of a Cyclopean city of no architecture known to man or to human imagination, with vast aggregations of night-black masonry embodying monstrous perversions of geometrical laws. There were truncated cones, sometimes terraced or fluted, surmounted by tall cylindrical shafts here and there bulbously enlarged and often capped with tiers of thinnish scalloped disks; and strange beetling, table-like constructions suggesting piles of multitudinous rectangular slabs or circular plates or five-pointed stars with each one overlapping the one beneath. There were composite cones and pyramids either alone or surmounting cylinders or cubes or flatter truncated cones and pyramids, and occasional needle-like spires in curious clusters of five. All of these febrile structures seemed knit together by tubular bridges crossing from one to the other at various dizzy heights, and the implied scale of the whole was terrifying and oppressive in its sheer gigantism. (At the Mountains of Madness, my italics)

SQ/RO? This Kantian split between an object’s sensuous properties and what its essence is implied to be, occurs in the classic description of the idol of Cthulhu:

If I say that my somewhat extravagant imagination yielded simultaneous pictures of an octopus, a dragon, and a human caricature, I shall not be unfaithful to the spirit of the thing. A pulpy, tentacled head surmounted a grotesque and scaly body with rudimentary wings; but it was the general outline of the whole which made it most shockingly frightful. (“The Call of Cthulhu,” my italics)

SO/RQ? Harman admits it’s rare in Lovecraft, (and elsewhere, though he finds hints of it in Leibniz) but he finds a few examples where scientific investigation reveals new, unheard of properties in some eldritch or trans-Plutonian object.

In every quarter, however, interest was intense; for the utter alienage of the thing was a tremendous challenge to scientific curiosity. One of the small radiating arms was broken off and subjected to chemical analysis. Professor Ellery found platinum, iron and tellurium in the strange alloy; but mixed with these were at least three other apparent elements of high atomic weight which chemistry was absolutely powerless to classify. Not only did they fail to correspond with any known element, but they did not even fit the vacant places reserved for probable elements in the periodic system. (“Dreams in the Witch House”)

And RO/RQ? You don’t want to know, as Lovecraft’s protagonists usually discover too late. It’s the inconceivable object whose surface properties only hint at yet further levels of inconceivable monstrosity within. Usually, Lovecraft relies on just slapping a weird name on something and hinting at the rest, as in:

[O]utside the ordered universe [is] that amorphous blight of nethermost confusion which blasphemes and bubbles at the center of all infinity—the boundless daemon sultan Azathoth, whose name no lips dare speak aloud, and who gnaws hungrily in inconceivable, unlighted chambers beyond time and space amidst the muffled, maddening beating of vile drums and the thin monotonous whine of accursed flutes. (Dream Quest of Unknown Kaddath)

You can see, in each case, how the horrific effect, and the usability for Harman’s ontography, would entirely disappear if given a Wilsonian “paraphrase”: It was a squid with wings! The object, when analyzed, revealed new, hitherto unknown elements!

Confused yet? Bored? Don’t worry. The whole point of Harman’s book, to which he devotes the vast portion of the text, is analyzing passages from Lovecraft that provide vivid illustrations of one or more of these gaps. In this way Harman’s ontography acquires its Hölderlin, and Lovecraft is rescued from pulp purgatory.

While there is considerable interest in Heidegger on alt-Right sites such as this one,[9] I’m sure there is considerably more general interest in Lovecraft. But Harman’s whole book is clearly and engagingly written, avoiding both oracular obscurity and overly-chummy vulgarity; since Harman is admirably clear even when discussing himself or Husserl, no one should feel unqualified to take on this unique—Lovecraftian?—conglomeration of philosophy and literary criticism.

The central Part Two is almost 200 pages of close readings of exactly 100 passages from Lovecraft. As such, it exhibits a good deal of diminishing returns through repetition, and the reader may be forgiven for skipping around, perhaps to their own favorite parts. And there’s certainly no point in offering my own paraphrases!

Nevertheless, over and above the discussion of individual passages as illustrations of Speculative Realism, Harman has a number of interesting insights into Lovecraft’s work generally. It’s also here that Harman starts to reveal some of his assumptions, or biases, or shall we say, context.

“Racism”

Harman, who, word on the blogs seems to be, is a run-of-the-mill liberal rather than a po-mo freak like his fellow “European philosophers,”[10] tips his hand early by referring dismissively to criticism of Lovecraft as pulp being “merely a social judgment, no different in kind from not wanting one’s daughter to marry the chimney sweep” (“Preliminary Note”). And we know how silly that would be! So needless to say, Lovecraft’s forthright, unmitigated, non-evolutionary (as in Obama’s “My position on gay marriage has evolved”) views on race need to be disinfected if Harman is to be comfortable marrying his philosophy to Lovecraft’s writing.

His solution is clever, but too clever. Discussing the passage from “Call of Cthulhu” where the narrator—foolishly as it happens—dismisses a warning as coming from “an excitable Spaniard” Harman suggests that the racism of Lovecraft’s protagonists[11] adds an interesting layer of—of course!—irony to them. As so often, we the reader are “smarter” than the smug protagonist, who will soon be taken down a few pegs.

But this really won’t do. Lovecraft’s protagonists are not stupid or uninformed, but rather too well-informed, hence prone to self-satisfaction that leads them where more credulous laymen might balk. “They’s ghosts in there, Mister Benny!”

Unfortunately for Harman, Lovecraft was above all else a Scientist, or simply a well-educated man, and the Science of his day was firmly on the side of what today would be called Human Biodiversity or HBD.[12] Harman may, like most “liberals” find that distasteful, something not to be mentioned, like Victorians and sex—a kind of “liberal creationism” as it’s been called—but that’s his problem.

It would be more interesting to adopt a truly Lovecraftian theme and take his view, or settled belief, that Science, or too much Science, was bad for us; just as Copernicus etc. had dethroned man for the privileged center of the God’s universe, the “truth” about Cthulhu and the other Elder Gods—first, there very existence, then the implication that they are the reality behind everyday religions—has a deflationary, perhaps madness inducing, effect.

Consider this famous quotation from the opening of “The Call of Cthulhu” as quoted by Harman himself in Part Two:

The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but someday the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

Thus Harman could argue that HBD may be true but bad for us to know—something very like the actual position of such liberal Comstocks as Richard Lewontin.

Consider, to switch genres, Dr. No. Quarrel [4], the ignorant, superstitious but loyal native retainer, is afraid to land on Crab Key, due to the presence of a dragon. Bond and his American buddy Leiter mock his fear. (Leiter: “Hey Quarrel, if you see a dragon, you get in first and breathe on him. With all that rum in you, he’ll die happy.”) But of course the dragon—which turns out to be a flame-throwing armored tractor—incinerates Quarrel whilst Bond and the equally superstitious but much more toothsome Honey Ryder are taken prisoner. While in this genre we know that Bond is the heroic knight who will ultimately slay the dragon, for now he does seem to be what Dr. No calls him, “just another stupid policeman” who would have done well to listen to the native—not unlike any number of Lovecraft’s educated protagonists.[13]

This smug assumption that knowledge leaves us safe, and indeed safer, is what Lovecraft is satirizing when the narrator of “Call of Cthulhu” dismisses the warnings of the “excitable Spaniard,” not, as Harman would have it, lampooning “racism” on some meta-level.[14]

Also, Michel Houllebeq, an author Harman otherwise praises, has emphasized that Lovecraft is anything but self-assured, either as a White man, or for the White race itself.[15] If “racism” is able to play the self-debunking role Harman wants it to, this is only because of Lovecraft’s self-doubts, based on his horrific experiences in the already multi-culti New York City of the 1920s, that the White race would be able to survive the onslaught of the inferior but strong and numerous under-men. As Houellebecq says, Lovecraft learned to take “racism back to its essential and most profound core: fear.”

“Fascistic Socialism”

On a related point, Harman puts this phrase, from Lovecraft’s last major work, The Shadow out of Time (which he generally dislikes, for reasons we’ll dispute later), in italics with a question mark, and leaves it at that, as if just throwing his hands up and saying “well, I just don’t know!” Alas, this is one of Lovecraft’s most interesting ideas. Like several American men of letters, such as Ralph Adams Cram, Lovecraft concluded that Roosevelt’s New Deal was an American version of Fascism, but, unlike the Chamber of Commerce types who made the same identification, he approved of it for precisely that reason! [16]

More generally, “fascistic socialism” was essentially what Spengler and others of the Conservative Revolution movement in German advocated; for example [5]:

Hans Freyer studied the problem of the failure of radical Leftist socialist movements to overcome bourgeois society in the West, most notably in his Revolution von Rechts (“Revolution from the Right”). He observed that because of compromises on the part of capitalist governments, which introduced welfare policies to appease the workers, many revolutionary socialists had come to merely accommodate the system; that is, they no longer aimed to overcome it by revolution because it provided more or less satisfactory welfare policies. Furthermore, these same policies were basically defusing revolutionary charges among the workers. Freyer concluded that capitalist bourgeois society could only be overcome by a revolution from the Right, by Right-wing socialists whose guiding purpose would not be class warfare but the restoration of collective meaning in a strong Völkisch (“Folkish” or “ethnic”) state.

But then, Harman would have to discuss, or even acknowledge, ideas that give liberals nose-bleeds.

Weird Porn

Harman makes the important distinction that Lovecraft is a writer of gaps, who chooses to apply his talents of literary allusion to the content of horror; but gaps do not exclusively involve horror, and we can imagine writers applying the same skills to other genres, such as detective stories, mysteries, and westerns.[17] In fact,

A literary “weird porn” might be conceivable, in which the naked bodies of the characters would display bizarre anomalies subverting all human descriptive capacity, but without being so strange that the erotic dimension would collapse into a grotesque sort of eros-killing horror. (p. 4)

Harman just throws this out, but if it seem implausible, I would offer Michael Manning’s graphic novels as example of weird porn: geishas, hermaphrodites, lizards and horses—or rather, vaguely humanoid species that suggest snakes and horses, rather like Harman’s discussion of Max Black’s puzzle over the gap produced by the proposition “Men are wolves”—create a kind of steam punk/pre-Raphaelist sexual utopia.[18]

Prolixity

Speaking of Lovecraftian allusiveness not being anchored to horror or any particular genre or content, brings us to my chief interest, and chief disagreement, with Harman’s discussion of Lovecraft’s literary technique.

I knew we would have a problem when right from the start Harman adduces The Shadow out of Time as one of Lovecraft’s worst, since this is actually one of my favorites, and the one that first convinced me of his ability to create cosmic horror through the invocation of hideous eons of cosmic vistas. Harman first notes, in dealing with the preceding novella, At the Mountains of Madness, that while the first half would rank as Lovecraft’s greatest work if he had only stopped there, the second half is a huge letdown: Lovecraft seems to descend to the level of pulp content, as he has his scientists go on a long, tedious journey through the long abandoned subterranean home of the Elder Race, reading endless hieroglyphs and giving all kinds of tedious details of their “everyday” life.[19]

For Harman, “Lovecraft’s decline as a stylist becomes almost alarming here” (p. 225) and will continue—with a brief return to form with “Dreams in the Witch House,” where Harman makes the interesting observation that Lovecraft seems to be weaving in every kind of Lovecraftian technique and content into one grand synthesis— until it ruins the second half as well of Shadow.

In a series of articles here on Counter Currents—soon to be reprinted as part of my next book, The Eldritch Evola . . . & Others—I suggested that not only should Lovecraft’s infamous verbosity no more be a barrier to elite appreciation than the equally deplored but critically lauded “Late Style” of Henry James, but also, and more interestingly, that conversely, we could see James developing that same style as part of an attempt to produce the same effect as Lovecraft’s, which fans call “cosmicism [6]” but which I would rather call cosmic horror (akin to the “sublime” of Burke or Kant).[20] Or perhaps: Weird Realism.

While Harman has greatly contributed to a certain micro-analysis of Lovecraft’s style, he seems, like the critics of the Late James, to miss the big picture. Although useful for rescuing Lovecraft from pulp oblivion, he still limits Lovecraft’s significance to either mere literature, or illustrations of Harman’s ontography. I suggest this still diminishes Lovecraft’s achievement.

The work of Lovecraft, like James, has the not inconsiderable extra value, over and above any “literary” pleasure, of stilling the mind by its very longeurs, leaving us open and available to the arising of some other, deeper level of consciousness when the gaps arise.[21]

But this is not on the table here, because Harman, like all good empiricists (and we are all empiricists today, are we not?) rejects, or misconstrues, the very idea of our having access to a super-sensible grasp of reality that would leap beyond, or between, the gaps; what in the East, and the West until the rise of secularism, would be called intellectual intuition.[22]

Reality itself is weird because reality itself is incommensurable with any attempt to represent or measure it. Lovecraft is aware of this difficulty to an exemplary degree, and through his assistance we may be able to learn about how to say something without saying it—or in philosophical terms, how to love wisdom without having it. When it comes to grasping reality, illusion and innuendo are the best we can do. (p. 51, my italics)

As usual in the modern West, we are to shoulder on as best we can, in an empty, meaningless world, comforted only by patting ourselves on the back for being too grown up, too “smart,” to believe we can not only pursue wisdom, but reach it. As René Guénon put it, it is one of the peculiarities of the modern Westerner to substitute a theory of knowledge for the acquisition of knowledge.[23]

Notes

1. On such “private associations” see Hesse, The Glass Bead Game, (New York: Holt, 1969), pp. 70–71.

2. Whose biographer, Greg Johnson, is not to be confused with our own Greg Johnson here at Counter Currents—I think. For the fictionalized Hilberry see The Hungry Ghosts: Seven Allusive Comedies (Boston: Black Sparrow Press, 1974). Allusive—there’s that idea again!

3. Did they succeed? Judge for yourself: Thomas Moore: Care of the Soul: Guide for Cultivating Depth and Sacredness in Everyday Life (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1992).

4. Eventually he would sink so low as to teach “everyday reasoning” to freshman lunkheads.

5. See Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain and Doktor Faustus, respectively.

6. The hero of this vindication of Rhetoric over Dialectic turns out to be . . . McLuhan! The medium is the message—don’t be hypnotized by the content, take a look at the all-important effects of the context. I’ve suggested before that my own work be seen, like McLuhan’s, less as dogmatic theses to be defended or refuted (dogmatism is for Harman the great sin of worshipping mere content) but rather as a series of probes for revealing new contexts for old ideas. See my Counter-Currents Interview in The Homo and the Negro as well as my earlier “You Mean My Whole Fallacy Is Wrong!” here [7]. Once more, we find that education at a Catholic college in the Canadian boondocks is the best preparation for grasping post-modernism, no doubt because it reproduces the background of Brentano and Heidegger. It was Canadian before it was cool!

7. The Wilson treatment is on display whenever some Judeo-con or Evangelical quotes passages from some alien religious work—usually the Koran these days—to show how stupid or bloodthirsty the natives are, while ignoring similar or identical passages in his own Holy Book. So-called “scholars” play the same game, questioning the authenticity of some newly discovered Gnostic work like the Gospel of Judas for containing, “absurdities” and “silliness” while finding nothing odd about the reanimated corpses—reminiscent of Lovecraft’s genuinely pulp hackwork Herbert West, Reaminator—of the “orthodox” writings. Indeed, some have suggested that Lovecraft’s Necronomicon is itself a parody of The Bible, its supposed Arab authorship a mere screen. This typically Semitic strategy of deliberately ignoring the allusive context of your opponent’s words while retaining your own was diagnosed by the Aryan Christ, in such well-known fulminations against the Pharisees as Matthew 23:24 : “You strain at a gnat, and swallow a camel” or Matthew 7:3: “And why beholdest thou the mote that is in thy brother’s eye, but considerest not the beam that is in thine own eye?”

8. Bad sci/fi hits rock bottom in the content-oriented department with the ubiquitous employment of the “space” prefix: space-food, space-pirates, space-justice, etc., frequently mocked on MST3K. David Bowie’s space-rock ode “Moonage Daydream” contains the cringe-worthy “Press your space face close to mine” but this is arguably a deliberate parody, while the rest of the song brilliantly exploits the Lovecraftian allusive/contextual mode of horror, moving from its straight-faced opening—“I’m an alligator”—through a series of Cthulhuian composites—“Squawking like a pink monkey bird”—ultimately veering into Harman’s weird porn mode—“I’m a momma-poppa coming for you.” Deviant sex and cut-up lyrics—another context-shredding technique—clearly points to the influence of William Burroughs, who created subversive texts based on various genres of boys’ books ranging from sci/fi (Nova Express) to detective (Cities of Red Night: “The name is Clyde Williamson Snide. I am a private asshole.”) to his alt-Western masterpiece The Western Lands trilogy.

9. Harman does a better job explaining Husserl and Heidegger than my little Marrano, but then he has had another three decades to work on it. He does, however, focus mainly on Heidegger’s tool analysis, and his own, somewhat broader formulation. For a wider focused, more objective, if you will, presentation of Heidegger, see Collin Cleary’s series of articles on this site, starting here [8].

10. Needless to say, he never notices that his liberalism is rooted in the ultimate dogma-affirming, context-ignoring movement, Luther’s “sola scriptura.” His liberalism is such as to allow him to tell a pretty amusing one-liner about Richard Rorty, but only by attributing it to “a colleague.” On the one hand, he cringes for Heidegger for daring to refer to a “Senegal Negro” (p. 59) but dismisses Emmanuel Faye’s “Heidegger is a Nazi” screed as a “work of propaganda” (p. 259). See Michael O’Meara’s review of Faye here [9].

11. “Not even Poe [another embarrassing “racist”, well what do you know?] has such indistinguishable protagonists” (p. 10).

12. Indeed, “racism” is one of those principles Baron Evola evoked in his Autodefesa [10], as being “those that before the French Revolution every well-born person considered sane and normal.”

13. Kingsley Amis has cogently argued that the key to Bond’s appeal is that he’s just like us, only a little better trained, able to read up on poker or chemin de fer, has excellent shooting instructors, etc. But if we had the chance . . . See Amis, Kingsley The James Bond Dossier (London: Jonathan Cape, 1965).

14. It might be interesting to apply Harman’s OOO to a film like Carpenter’s They Live. In my review of Lethem’s book on the movie [11], reprinted in The Homo and the Negro, I mentioned liking another point, also from Slavoj Žižek: contrary to the smug assumptions of the Left, knowledge is not necessarily something people want, or which is pleasant—hence the protagonist has to literally beat his friend into putting on the reality-revealing sunglasses. Here we have both Lovecraft’s gaps and notion that knowledge is more likely something you’ll regret: Lovecraft and Žižek, together again!

15. Michel Houellebecq [12], H. P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life [13] (London: Gollancz, 2008). See more generally, and from the same period, Lothrop Stoddard, The Revolt Against Civilization: The Menace of the Under Man, ed. Alex Kurtagic, introduction by Kevin MacDonald (Shamley Green: The Palingenesis Project, 2011).

16. See my “Ralph Adams Cram: Wild Boy of American Architecture” here [14].

17. Again, just as Burroughs applied his cut-up technique to various pulp genres.

18. See my discussion of Manning in “The Hermetic Environment and Hermetic Incest: The True Androgyne and the ‘Ambiguous Wisdom of the Female’” here [15].

19. Everyday life of pre-Cambrian radiata with wings, of course.

20. My suggestion was based on some remarks of John Auchard in Penguin’s new edition of the Portable Henry James, that James’s work could be seen as part of the attempt to substitute art for religion, by using the endless accumulation of detail—James’s “prolixity” as Lovecraft himself chides him for—to “saturate” everyday experience with meaning.

21. Colin Wilson’s second Lovecraftian novel, The Philosopher’s Stone (Los Angeles: Tarcher, 1971)—originally published in 1969, republished in a mass market edition in 1971 at the request of, and with a Foreword by, Joyce Carol Oates, bringing us back to Hilberry—introduced me to the idea of length, and even boredom, as spiritual disciplines. One of the main characters “seemed to enjoy very long works for their own sake. I think he simply enjoyed the intellectual discipline of concentrating for hours at a time. If a work was long, it automatically recommended itself to him. So we have spent whole evenings listening to the complete Contest Between Harmony and Invention of Vivaldi, the complete Well Tempered Clavier, whole operas of Wagner, the last five quartets of Beethoven, symphonies of Bruckner and Mahler, the first fourteen Haydn symphonies. . . . He even had a strange preference for a sprawling, meandering symphony by Furtwängler [presumably the Second], simply because it ran on for two hours or so.” The book is available online here [16].

22. With the inconsistency typical of a Modern trying to conduct thought after cutting off the roots of thought, Harman advises us that “It takes a careful historical judge to weigh which [contextual] aspects of a given thing are assimilated by it, and which can be excluded” (p. 245). What makes a “careful” judge is, of course, intuition. Cf. my remarks on Spengler’s “physiognomic tact” and Guénon’s intellectual intuition in “The Lesson of the Monster; or, The Great, Good Thing on the Doorstep,” to appear in my forthcoming book The Eldritch Evola but also available here [17].

23. How one can transcend the limits of secular science and philosophy, without abandoning empirical experience as the Christian does with his blind “faith,” is the teaching found in Evola’s Introduction to Magic, especially the essay “The Nature of Initiatic Knowledge.” “Having long been trapped in a kind of magic circle, modern man knows nothing of such horizons. . . . Those who are called “scientists” today [as well as, even more so, “philosophers”] have hatched a real conspiracy; they have made science their monopoly, and absolutely do not want anyone to know more than they do, or in a different manner than they do.” The whole text is available online here [18].

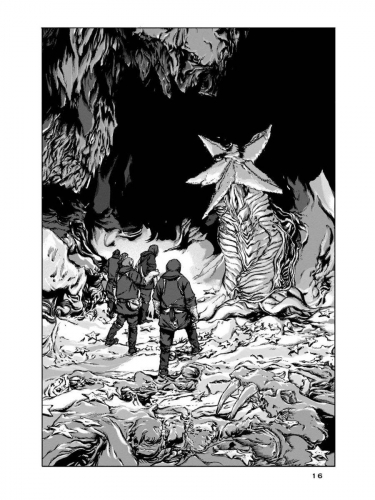

A group led by Lake sets off to investigate the source of the prints and discovers the remains of fourteen mysterious amphibious specimens with star-shaped heads, wings, and triangular feet. They are highly evolved creatures, with five-lobed brains, yet the stratum in which they were found indicates that they are about forty million years old. Shortly thereafter, Lake and his team (with the exception of one man) are slaughtered. When Dyer and the others arrive at the scene, they find six of the specimens buried in large “snow graves” and learn that the remaining specimens have vanished, along with several other items. Additionally, the planes and mechanical devices at the camp were tampered with. Dyer concludes that the missing man simply went mad, wreaked havoc upon the camp, and then ran away.

A group led by Lake sets off to investigate the source of the prints and discovers the remains of fourteen mysterious amphibious specimens with star-shaped heads, wings, and triangular feet. They are highly evolved creatures, with five-lobed brains, yet the stratum in which they were found indicates that they are about forty million years old. Shortly thereafter, Lake and his team (with the exception of one man) are slaughtered. When Dyer and the others arrive at the scene, they find six of the specimens buried in large “snow graves” and learn that the remaining specimens have vanished, along with several other items. Additionally, the planes and mechanical devices at the camp were tampered with. Dyer concludes that the missing man simply went mad, wreaked havoc upon the camp, and then ran away.

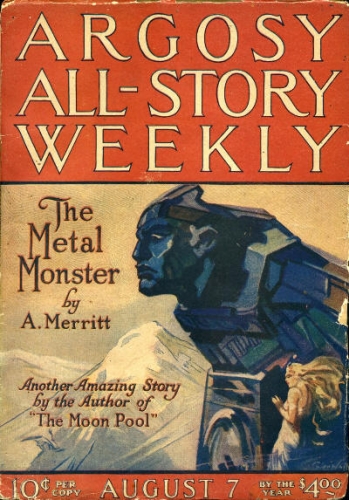

L'interlocuteur n'est pas un homme de chair et de sang, mais un personnage de papier: John Kenton, le protagoniste de la Nef d'Ishtar, dont la nouvelle édition vient d'arriver dans les librairies d'Italie grâce aux efforts d'Il Palindromo. En réalité, il s'agit de bien plus qu'une réédition: à l'ère des réimpressions anastatiques et des rééditions sans mise à jour, il est gratifiant de voir qu'il existe des maisons d'édition qui pensent différemment. Giuseppe Aguanno, directeur de la série qui a accueilli le livre, "I tre sedili deserti" (également palindrome, essayez de lire le nom à l'envers...), ne s'est pas limité à exhumer le roman, sorti il y a exactement quarante ans dans le légendaire "Futuro" de Fanucci, édité par Gianfranco de Turris et Sebastiano Fusco, mais a en fait lancé un autre livre : nouvelle traduction (basée sur son édition en série, dans les colonnes de Argosy All-Story Weekly), nouvelles notes sur le texte, appareil critique inédit, glossaire mythologique, profil biographique de l'auteur, ainsi que les magnifiques illustrations de Virgil Finlay qui ont accompagné sa première parution. Bref, on ne pouvait pas demander mieux ; pour une fois, une petite maison d'édition a adopté un soin éditorial qui aurait beaucoup à apprendre même à des réalités éditoriales beaucoup plus "établies".

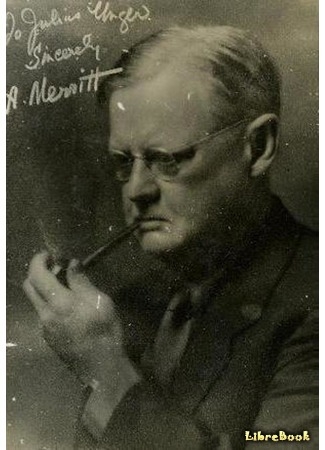

L'interlocuteur n'est pas un homme de chair et de sang, mais un personnage de papier: John Kenton, le protagoniste de la Nef d'Ishtar, dont la nouvelle édition vient d'arriver dans les librairies d'Italie grâce aux efforts d'Il Palindromo. En réalité, il s'agit de bien plus qu'une réédition: à l'ère des réimpressions anastatiques et des rééditions sans mise à jour, il est gratifiant de voir qu'il existe des maisons d'édition qui pensent différemment. Giuseppe Aguanno, directeur de la série qui a accueilli le livre, "I tre sedili deserti" (également palindrome, essayez de lire le nom à l'envers...), ne s'est pas limité à exhumer le roman, sorti il y a exactement quarante ans dans le légendaire "Futuro" de Fanucci, édité par Gianfranco de Turris et Sebastiano Fusco, mais a en fait lancé un autre livre : nouvelle traduction (basée sur son édition en série, dans les colonnes de Argosy All-Story Weekly), nouvelles notes sur le texte, appareil critique inédit, glossaire mythologique, profil biographique de l'auteur, ainsi que les magnifiques illustrations de Virgil Finlay qui ont accompagné sa première parution. Bref, on ne pouvait pas demander mieux ; pour une fois, une petite maison d'édition a adopté un soin éditorial qui aurait beaucoup à apprendre même à des réalités éditoriales beaucoup plus "établies". Les mots cités sont ceux du protagoniste du roman, mais pourraient également faire référence à son auteur, Abraham Merritt (photo, ci-contre). Journaliste et écrivain, botaniste et spécialiste des substances hallucinogènes, ses multiples vies l'ont mené de l'archéologie à la mythologie, de l'histoire comparée des religions au folklore. Cet aventurier et archéologue du merveilleux ne s'est pas contenté d'étudier des livres, s'il est vrai, par exemple, qu'il a visité la cité maya de Tulum, au Mexique, qu'il a cherché des trésors dans le Yucatan (qu'il a trouvés plus tard...) et qu'il est devenu membre d'une tribu indienne, après une initiation régulière.

Les mots cités sont ceux du protagoniste du roman, mais pourraient également faire référence à son auteur, Abraham Merritt (photo, ci-contre). Journaliste et écrivain, botaniste et spécialiste des substances hallucinogènes, ses multiples vies l'ont mené de l'archéologie à la mythologie, de l'histoire comparée des religions au folklore. Cet aventurier et archéologue du merveilleux ne s'est pas contenté d'étudier des livres, s'il est vrai, par exemple, qu'il a visité la cité maya de Tulum, au Mexique, qu'il a cherché des trésors dans le Yucatan (qu'il a trouvés plus tard...) et qu'il est devenu membre d'une tribu indienne, après une initiation régulière.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

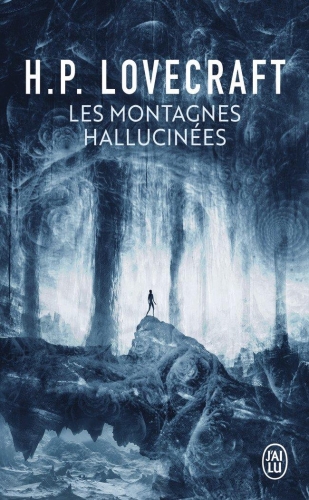

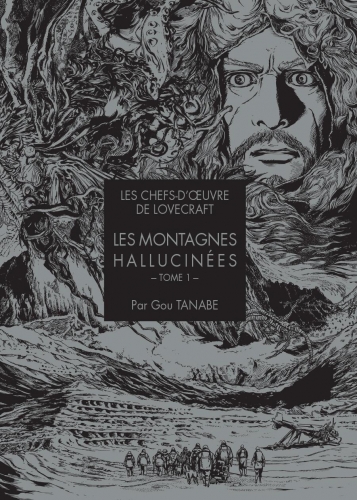

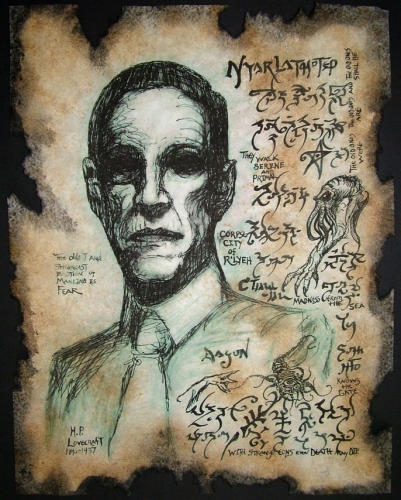

Mais avant cela, il faut tout d’abord revenir sur quelques caractéristiques majeurs, ainsi que quelques grands thèmes présents,pour ne pas dire constitutifs, de l’œuvre de Lovecraft. Évidemment il y a tout d’abord ces entités primordiales monstrueuses, ces abominations répondant aux noms de Yog-Sothoth, Nyarlathotep ou bien encore Cthulhu. A l’instar de nombreux éléments qui façonnent l’univers de l’auteur, son panthéon noir est sujet à l’intertextualité : le lecteur retrouvera ces monstruosités dans divers nouvelles indépendantes des unes des autres. Ces horreurs sont également citées dans des livres, le plus souvent des vieux grimoires comme le Necronomicon, les Manuscrits Pnakotiques, l’Unaussprechlichen Kulten,etc, eux-aussi présents dans la plupart des écrits de Lovecraft (et il en est de même pour certains lieux, bien réels ou imaginaires). L’intertextualité constitue une véritable toile de fond qui contribue à la création de l’univers « lovecraftien ».

Mais avant cela, il faut tout d’abord revenir sur quelques caractéristiques majeurs, ainsi que quelques grands thèmes présents,pour ne pas dire constitutifs, de l’œuvre de Lovecraft. Évidemment il y a tout d’abord ces entités primordiales monstrueuses, ces abominations répondant aux noms de Yog-Sothoth, Nyarlathotep ou bien encore Cthulhu. A l’instar de nombreux éléments qui façonnent l’univers de l’auteur, son panthéon noir est sujet à l’intertextualité : le lecteur retrouvera ces monstruosités dans divers nouvelles indépendantes des unes des autres. Ces horreurs sont également citées dans des livres, le plus souvent des vieux grimoires comme le Necronomicon, les Manuscrits Pnakotiques, l’Unaussprechlichen Kulten,etc, eux-aussi présents dans la plupart des écrits de Lovecraft (et il en est de même pour certains lieux, bien réels ou imaginaires). L’intertextualité constitue une véritable toile de fond qui contribue à la création de l’univers « lovecraftien ». Cette dialectique s’accompagne ainsi d’une atmosphère anti-moderne palpable, voir d’un véritable retour à l’archaïque (type de sculptures, d’architectures, de sociétés humaines, etc). Mais, encore une fois, H.P.Lovecraft pouvait également s’intéresser à des « tendances » de son époque, comme l’eugénisme. Certes Lovecraft était raciste et antisémite – les pseudo-journalistes et autres écrivaillons n’oublient jamais de gloser là-dessus bien évidemment – mais c’est surtout la dégénérescence atavique qui est intéressant chez lui. Les nouvelles La peur qui rode et surtout Le cauchemar d’Innsmouth mettent horriblement en avant ces thèmes, voir aussi celui du Destin.

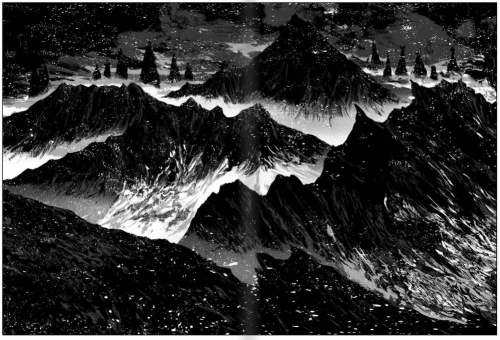

Cette dialectique s’accompagne ainsi d’une atmosphère anti-moderne palpable, voir d’un véritable retour à l’archaïque (type de sculptures, d’architectures, de sociétés humaines, etc). Mais, encore une fois, H.P.Lovecraft pouvait également s’intéresser à des « tendances » de son époque, comme l’eugénisme. Certes Lovecraft était raciste et antisémite – les pseudo-journalistes et autres écrivaillons n’oublient jamais de gloser là-dessus bien évidemment – mais c’est surtout la dégénérescence atavique qui est intéressant chez lui. Les nouvelles La peur qui rode et surtout Le cauchemar d’Innsmouth mettent horriblement en avant ces thèmes, voir aussi celui du Destin. En 1930, une expédition en Antarctique est organisée par l’Université Miskatonic. Celle-ci est composée de nombreux scientifiques et d’étudiants : biologistes, géologues, et physiciens. Ayant établi leur QG sur le mont Erebus, les premières découvertes ne tardent pas à voir le jour. Enthousiasmé, le Professeur Lake décide de poursuivre les recherches au nord-ouest. C’est en arrivant sur place qu’ils vont découvrir une chaîne de montagnes plus haute encore que l’Himalaya. Une fois leur camp installé, l’équipe met à jour une grotte abritant des restes de créatures inconnues, mi-animales, mi-végétales, que le Pr. Lake baptisera « les Anciens », en référence à la description de créatures semblables dans le Necronomicon. Une violente tempête s’abat sur la région et le contact entre les deux équipes est coupée. Le Professeur Dyer décide d’aller aider ses confrères partis au nord-ouest. Sur place, ils ne trouveront que les cadavres horriblement mutilés de l’équipe et des chiens de traîneau. Seul manque à l’appel Gedney, l’assistant de Lake, et un chien…

En 1930, une expédition en Antarctique est organisée par l’Université Miskatonic. Celle-ci est composée de nombreux scientifiques et d’étudiants : biologistes, géologues, et physiciens. Ayant établi leur QG sur le mont Erebus, les premières découvertes ne tardent pas à voir le jour. Enthousiasmé, le Professeur Lake décide de poursuivre les recherches au nord-ouest. C’est en arrivant sur place qu’ils vont découvrir une chaîne de montagnes plus haute encore que l’Himalaya. Une fois leur camp installé, l’équipe met à jour une grotte abritant des restes de créatures inconnues, mi-animales, mi-végétales, que le Pr. Lake baptisera « les Anciens », en référence à la description de créatures semblables dans le Necronomicon. Une violente tempête s’abat sur la région et le contact entre les deux équipes est coupée. Le Professeur Dyer décide d’aller aider ses confrères partis au nord-ouest. Sur place, ils ne trouveront que les cadavres horriblement mutilés de l’équipe et des chiens de traîneau. Seul manque à l’appel Gedney, l’assistant de Lake, et un chien…

S. T. Joshi

S. T. Joshi

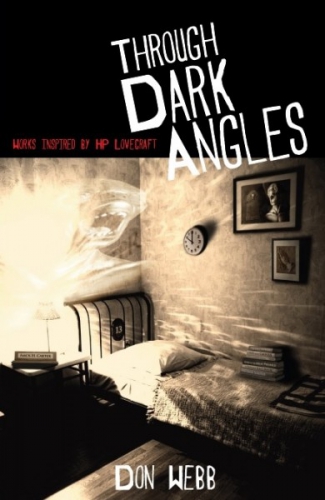

But therein lies their charm. Consider this collection, to continue the pop culture metaphor, a kind of Lovecraft Unplugged.

But therein lies their charm. Consider this collection, to continue the pop culture metaphor, a kind of Lovecraft Unplugged.

Don Webb has been writing short stories, and the occasional novel, since, as a rather indifferent undergraduate at Texas Tech, he took a supposedly easy-A class in “The Science Fiction Short Story” and discovered that unlike his fellow slackers, he’d rather take the write a story option than the term paper. The story itself was equally indifferent, but by then the hook was in, a writer born.

Don Webb has been writing short stories, and the occasional novel, since, as a rather indifferent undergraduate at Texas Tech, he took a supposedly easy-A class in “The Science Fiction Short Story” and discovered that unlike his fellow slackers, he’d rather take the write a story option than the term paper. The story itself was equally indifferent, but by then the hook was in, a writer born.