lundi, 27 novembre 2023

Pierre Le Vigan: Les limites de la morale de Kant

Pierre Le Vigan:

Les limites de la morale de Kant

Kant (1724-1804) a proposé aussi bien une théorie de l’esthétique que de la morale, et de la connaissance. A chaque fois, il s’agit de sortir du psychologisme et de dégager les conditions d’un jugement a priori, dit encore transcendantal. La règle qu’essaie d’appliquer Kant a tous ses écrits est celle-ci : ne pas en dire plus que ce que l’on sait. Savoir ce que l’on sait, savoir ce que l’on ne sait pas. C’est ainsi que Kant aborde la philosophie. Une des grandes questions qu’aborde Kant est celle-ci : dans quelle mesure peut-on avoir des connaissances certaines en métaphysique, tout comme en mathématique et en physique ? Les notions métaphysiques ont été pensées a priori dans la philosophie. A priori : c’est-à-dire au-delà de l’expérience. Peut-on continuer à les penser comme cela ? Kant nous dit : il faut distinguer la forme des connaissances et la matière de la connaissance. La forme dépend de nous, la matière nous est déjà donnée. Kant va nous dire : l’esprit intervient dans la connaissance des choses (c’est en ce sens qu’on pourra parler d’idéalisme, sans que cela soit l’esprit qui crée les choses). L’expérience ne suffit pas à déterminer ce que sont les choses a priori, puisque l’expérience est justement postérieure à l’apparition des choses (idée contestable sur le fond mais logique dans la conception de Kant). L’expérience ne concerne que des cas particuliers. Nous observons que le soleil se lève tous les jours. Cela ne suffit pas à nous donner la certitude qu’il se lèvera demain. Une fréquence de répétition statistique ne produit pas une preuve logique.

Seule la raison permet de déterminer une proposition nécessaire (selon laquelle il ne peut en être autrement) et universelle (il en sera ainsi quelles que soient les circonstances) avant l’expérience. La mathématique et la physique, contrairement à la métaphysique, comportent ainsi des jugements synthétiques a priori. De quoi s’agit-il ? Des jugements synthétiques sont des jugements qui apportent quelque chose de plus à l’information incluse dans la proposition. Exemple : « un chat est un félin » n’est pas une proposition synthétique. C’est une proposition analytique. Rien de nouveau n’est dit, car tous les chats sont des félins. Cela est dans la définition même du chat. Par contre, « un chat peut faire des km pour retrouver son maitre » est une proposition synthétique. La raison en est que cela n’est pas dans la définition du chat. C’est une information supplémentaire.

Comment se construit la connaissance ? Les jugements, synthétiques ou analytiques, se font sur la base de notions qui existent a priori dans notre entendement. Ainsi, l’espace et le temps sont des formes a priori de la sensibilité, nous dit Kant. « Tout objet de la sensibilité doit se conformer aux intuitions pures de l’espace et du temps », rappelle Victor Delbos, et c’est l’objet de l’esthétique transcendantale de Kant dans sa Critique de la raison pure. Ces formes n’existent pas dans la matière elle-même (ici, Kant n’est pas matérialiste, alors que, pourtant, il ne nie pas l’existence des objets extérieurs à l’homme. Mais il ne pense pas que l’espace et le temps soient des propriétés mêmes de la matière. Ce sont pour lui des propriétés de la noèse, c’est-à-dire de la saisie des choses, noèmes, par notre entendement). Il y a d’autres formes a priori de l’entendement, ce sont ce que Kant appelle les catégories, qui sont l’objet de l’analytique transcendantale. Il y a ainsi un chemin qui va de la sensibilité à l’entendement, puis à la raison. Cette dernière produit les idées, mais ne peut atteindre la connaissance des choses en soi, que Kant appelle des noumènes. Cette incapacité de la raison à saisir les choses en soi est l’objet de la dialectique transcendantale. Les idées de la raison, Dieu, l’âme, le monde sont ce que l’on peut penser, mais que l’on ne peut connaitre. C’est le domaine de la métaphysique, c’est-à-dire des hypothèses à la fois nécessaires et non démontrables, au-delà de toute possibilité de preuve.

Une architecture de la pensée de Kant se dessine alors. Kant rappelle que la philosophie se divise en logique, physique et éthique. La logique est formelle. Elle relève des règles de la raison. La physique et l’éthique renvoient respectivement aux choses de la nature, et aux choses des hommes. C’est ainsi qu’il doit y avoir une métaphysique de la nature, et une métaphysique des mœurs, qui concerne les hommes. Il s’agit de savoir, dans les deux cas, comment connaitre la règle à suivre, pour que la volonté, que l’on suppose libre, se détermine en fonction de règles a priori. La raison s’applique aussi bien à la connaissance physique qu’à la connaissance des règles morales, et la volonté n’est pas autre chose que la raison pratique. Elle est aussi « pure » (c’est-à-dire préalable à l’expérience) que la raison pure théorique (de theoria, voir le monde, l’examiner).

Une architecture de la pensée de Kant se dessine alors. Kant rappelle que la philosophie se divise en logique, physique et éthique. La logique est formelle. Elle relève des règles de la raison. La physique et l’éthique renvoient respectivement aux choses de la nature, et aux choses des hommes. C’est ainsi qu’il doit y avoir une métaphysique de la nature, et une métaphysique des mœurs, qui concerne les hommes. Il s’agit de savoir, dans les deux cas, comment connaitre la règle à suivre, pour que la volonté, que l’on suppose libre, se détermine en fonction de règles a priori. La raison s’applique aussi bien à la connaissance physique qu’à la connaissance des règles morales, et la volonté n’est pas autre chose que la raison pratique. Elle est aussi « pure » (c’est-à-dire préalable à l’expérience) que la raison pure théorique (de theoria, voir le monde, l’examiner).

Comment peut-on connaitre les éléments de la métaphysique ? Il faut d’abord dire ce que sont ces éléments. Ce sont ce que nous avons appelé les « idées de la raison », toutes les questions sur le monde (son origine), l’âme (éternelle ou pas, créée ou pas), Dieu (existe-il ou pas ?). La métaphysique devrait, pour exister, sortir de l’analytique, c’est-à-dire de la tautologie. Comment en sortir si ce n’est par des jugements synthétiques ? Or, on observe qu’il n’y a pas de jugements synthétiques a priori en métaphysique. On peut dire que Dieu est Dieu, mais on ne peut rien dire de Dieu. On peut dire que l’âme est l’âme ou qu’elle est l’esprit, ce qui est un synonyme, mais on ne peut rien dire de l’âme. Etc. Nous ne savons rien de ces choses car nous ne les avons pas expérimentées. Nous ne pouvons donc avoir en métaphysique de jugement synthétique a posteriori (comme « le feu brûle »), ni a priori comme dans les mathématiques ou la physique. Citons comme exemple de jugement synthétique a priori dans les mathématiques : « 5 + 7 = 12 ». C’est une information qui n’est pas contenue dans l’énoncé « 5 + 7 ». Ce qui est affirmable au-delà de toute expérience, comme en mathématique et en physique (loi de la gravitation par exemple), est donc un jugement a priori. On l’appelle aussi transcendantal. L’a priori est donc ce que l’on sait et qui précède l’expérience, ce qui rend inutile l’expérience pour le savoir, mais qui sera confirmé par l’expérience si elle a lieu. Pour résumer cela, Kant dit : « Des pensées sans matière sont vides ». C’est pourquoi la métaphysique concerne des choses qui ne peuvent être connues. En ce sens, la métaphysique n’existe pas. Les objets de la métaphysique, qui sont sans matière, peuvent être objets de pensées (cogitata), mais non de connaissance.

*

Cela veut dire que nous ne pouvons connaitre que des réalités sensibles. C’est pour cela que nous ne pouvons rien connaitre de la métaphysique. Nous pouvons la penser, nous pouvons y penser, mais non pas la connaitre. Les choses telles que nous les connaissons sont les phénomènes. Si nous étions des chats au lieu d’être des humains, les choses nous apparaitraient différemment. Les phénomènes seraient autres pour nous. Les choses pour soi seraient autres. Mais la science nous dit que les choses seraient les mêmes. Exemple. Un bruit qui apparait faible pour les humains apparait fort pour un chat. Le pour soi est différent. Il en serait de même pour un humain qui aurait une sensibilité excessive de l’oreille. Mais c’est le même bruit. La science nous permet de le graduer. Il est ainsi objectivement le même, mais le phénomène se manifeste pour nous différemment de ce qu’il en est pour les chats. La science nous permet donc de connaitre la chose en soi, ce que Kant appelle le noumène, et qu’il postule non connaissable. C’est pourquoi la distinction que fait Kant entre noumène et phénomène n’est sans doute pas pertinente. Mais il est certain que le phénomène est concret, et que le noumène (l’intensité d’un bruit mesuré scientifiquement par exemple) est abstrait. En tout état de cause, les objets de la métaphysique échappent à toute connaissance, aussi bien phénoménale que nouménale. Nous ne pouvons rien savoir d’un dieu qui serait créateur du monde, d’une âme qui serait immortelle, d’un monde qui serait créé par Dieu, etc. Pourquoi ? Parce qu’aucune connaissance objective n’est possible quant à ces objets. La métaphysique n’est pas une série de phénomènes, connaissables a postériori, et n’est pas non plus un ensemble de noumènes, connaissables a priori, scientifiquement, comme « 2 + 3 font 5 » ou comme « l’eau bout à 100 degrés et gèle à zéro degré ».

La métaphysique étant le domaine des incertitudes, nous ne savons donc pas si nous avons une âme mortelle ou immortelle, si Dieu existe, ni si nous sommes libres. Comment alors établir une morale, une règle de comportement, si nous ne sommes peut-être pas libres, si nous sommes donc soumis à des déterminations ? Les Fondements de la métaphysique des mœurs (1785) partent des connaissances rationnelles de la moralité. On tient pour acquis que ce qui doit être tenu pour bon est une bonne volonté. Ni la recherche du bonheur, ni l’intelligence, ni le courage ne sont des critères de moralité. La bonne volonté est le seul critère. Mais comment la caractériser ? Quand on agit par devoir. Ce qui est moral, ce qui est issu de bonne volonté, ce ne sont pas seulement les actions conformes au devoir, mais celles faites par devoir, et non pas parce que la conformité au devoir nous apporterait quelques avantages. Le commerçant honnête par intérêt n’est donc pas louable. Plus encore : celui qui fait le bien par « tempérament gentil » a moins de mérite que celui qui fait le bien par devoir, et non par inclination de sa sensibilité. La volonté doit accepter d’être en lutte contre nos inclinations naturelles. Il y a donc « séparation radicale entre les mobiles exclusivement issus du devoir et les mobiles issus des inclinations » (Victor Delbos in Kant, Fondements de la métaphysique des mœurs, Delagrave, 1900, rééd. 1986, p. 39).

La métaphysique étant le domaine des incertitudes, nous ne savons donc pas si nous avons une âme mortelle ou immortelle, si Dieu existe, ni si nous sommes libres. Comment alors établir une morale, une règle de comportement, si nous ne sommes peut-être pas libres, si nous sommes donc soumis à des déterminations ? Les Fondements de la métaphysique des mœurs (1785) partent des connaissances rationnelles de la moralité. On tient pour acquis que ce qui doit être tenu pour bon est une bonne volonté. Ni la recherche du bonheur, ni l’intelligence, ni le courage ne sont des critères de moralité. La bonne volonté est le seul critère. Mais comment la caractériser ? Quand on agit par devoir. Ce qui est moral, ce qui est issu de bonne volonté, ce ne sont pas seulement les actions conformes au devoir, mais celles faites par devoir, et non pas parce que la conformité au devoir nous apporterait quelques avantages. Le commerçant honnête par intérêt n’est donc pas louable. Plus encore : celui qui fait le bien par « tempérament gentil » a moins de mérite que celui qui fait le bien par devoir, et non par inclination de sa sensibilité. La volonté doit accepter d’être en lutte contre nos inclinations naturelles. Il y a donc « séparation radicale entre les mobiles exclusivement issus du devoir et les mobiles issus des inclinations » (Victor Delbos in Kant, Fondements de la métaphysique des mœurs, Delagrave, 1900, rééd. 1986, p. 39).

Le devoir étant indépendant de notre intérêt et de nos inclinations, son critère doit être la représentation que nous avons de la loi. C’est évidemment un critère tout à fait discutable, comme le montrera, à la limite, le procès Eichmann. Mais la légalité n’est pas la moralité. Elle n’est pas obligatoirement la loi morale. Celle-ci consiste à faire quelque chose qui peut être universalisé. Ce n’est pas seulement choisir le devoir plutôt que son inclination qui est bien, c’est choisir ce qui peut être universalisé. La raison entre donc dans le devoir, puisque, en me demandant ce qui peut ou non être universalisé, je fais appel à la raison. Le critère de la morale, ou encore de la raison pratique – comment se comporter ? – apparait ainsi assez simple, et plus simple que la raison théorique, celle qui permet la connaissance théorique du réel. La difficulté est que l’observation des actes comme phénomène ne nous dit pas s’ils ont été accomplis par devoir. Une « bonne sœur » a des actes qui paraissent plein de bonne volonté. Mais ne les accomplit-elle pas pour aller au paradis ? Dans ce cas, c’est par inclination et non par devoir. Ce n’est pas de la vraie morale. Voyons tel autre qui agit bien, selon la maxime d’une action universalisable : ne le fait-il pas par amour propre, ou par intérêt comme le pensait La Rochefoucauld ? Pour autre chose que le devoir ? La morale ne relève donc pas des exemples. Tout homme est doté de raison, tout homme a donc une volonté, même si nous avons vu, compte tenu de ce que nous ne pouvons rien dire de l’existence de Dieu, que la part de notre liberté reste quelque chose d’indéterminable. Mais pour Kant, puisque nous avons une volonté en conséquence de la raison, cette volonté est une raison pratique. Le devoir exprime le rapport entre la raison et une volonté. La raison s’impose à la volonté en contrecarrant si besoin la sensibilité. Elle s’impose par la contrainte. La raison est un impératif. Les impératifs sont hypothétiques quand ils existent en fonction d’une certaine finalité, tel l’impératif d’être prudent dans une ascension en montagne, ou l’impératif de prendre tel chemin pour aller à tel endroit. L’impératif est catégorique quand c’est un commandement indépendant d’une fin. C’est alors une loi de l’action. « Car il n’y a que la loi qui entraine avec soi le concept d’une nécessité inconditionnée, véritablement objective, par suite d’une nécessité universellement valable, et les commandements sont des lois auxquelles il faut obéir, c’est-à-dire se conformer même à l’encontre de l’inclination » (Fondements de la métaphysique des mœurs, 1785). La loi est une notion morale avant d’être la loi d’un Etat.

L’impératif catégorique est une proposition synthétique a priori, c’est-à-dire qu’il ne repose pas sur l’expérience et ne dépend pas d’elle. Il est du même ordre, dans la raison pure pratique, que les mathématiques dans la raison pure théorique. L’impératif catégorique se fonde sur ce qui anime la volonté. Voilà, nous dit Kant, ce que doit être le fondement de la volonté : « Agis uniquement d’après la maxime qui fait que tu peux vouloir en même temps qu’elle devienne une loi universelle » (Fondements de la métaphysique des mœurs). De quelle loi universelle s’agit-il ? Des lois universelles de la nature, qui veut le développement de la vie. Des lois de la vie de l’homme : il doit développer ses facultés et ne pas les laisser en jachère. La paresse est ainsi contraire à l’impératif catégorique. Il faut à la fois concevoir ce que nous voulons comme loi universelle, et vouloir que ce soit une loi universelle. La raison est sollicitée, et la volonté s’appuie sur son diagnostic. L’immoralité consiste à s’accorder des exceptions à la loi universelle. Le motif d’une action, la bonne volonté, prime toujours sur le résultat que l’on voudrait atteindre, sur le mobile de l’action. Mais le mobile lui-même est encadré. Ce mobile ne peut être que le bien de l’homme. « L’homme, et en général tout être raisonnable, existe comme fin en soi, et non pas simplement comme moyen dont telle ou telle volonté puisse user à son gré. » C’est le second impératif catégorique. De là la conclusion : « Agis de telle sorte que tu traites l’humanité, aussi bien dans ta personne que dans la personne de tout autre, toujours en même temps comme une fin, et jamais simplement comme un moyen. »

L’impératif catégorique est une proposition synthétique a priori, c’est-à-dire qu’il ne repose pas sur l’expérience et ne dépend pas d’elle. Il est du même ordre, dans la raison pure pratique, que les mathématiques dans la raison pure théorique. L’impératif catégorique se fonde sur ce qui anime la volonté. Voilà, nous dit Kant, ce que doit être le fondement de la volonté : « Agis uniquement d’après la maxime qui fait que tu peux vouloir en même temps qu’elle devienne une loi universelle » (Fondements de la métaphysique des mœurs). De quelle loi universelle s’agit-il ? Des lois universelles de la nature, qui veut le développement de la vie. Des lois de la vie de l’homme : il doit développer ses facultés et ne pas les laisser en jachère. La paresse est ainsi contraire à l’impératif catégorique. Il faut à la fois concevoir ce que nous voulons comme loi universelle, et vouloir que ce soit une loi universelle. La raison est sollicitée, et la volonté s’appuie sur son diagnostic. L’immoralité consiste à s’accorder des exceptions à la loi universelle. Le motif d’une action, la bonne volonté, prime toujours sur le résultat que l’on voudrait atteindre, sur le mobile de l’action. Mais le mobile lui-même est encadré. Ce mobile ne peut être que le bien de l’homme. « L’homme, et en général tout être raisonnable, existe comme fin en soi, et non pas simplement comme moyen dont telle ou telle volonté puisse user à son gré. » C’est le second impératif catégorique. De là la conclusion : « Agis de telle sorte que tu traites l’humanité, aussi bien dans ta personne que dans la personne de tout autre, toujours en même temps comme une fin, et jamais simplement comme un moyen. »

L’homme est à la fois le bénéficiaire et l’auteur de cette législation. C’est le principe de l’autonomie de la volonté. La volonté n’est pas déterminée par Dieu. Elle vient de l’homme. Cette loi morale établit un « règne des fins », qui est un idéal, et est l’équivalent du règne de la grâce par rapport au règne de la nature, ou règne de « ce qui est », chez Leibniz. De même que la volonté est libre, l’homme est libre. Si tu dois faire quelque chose, tu peux le faire. C’est par la raison que nous avons conscience de ce devoir. « En tant qu’il se connait uniquement par le sens intime, l’homme n’a qu’une existence phénoménale ; mais l’homme possède plus que la sensibilité, il possède même plus qu’un entendement, c’est-à-dire plus qu’une faculté qui, tout en étant active, doit se borner à lier selon les règles les représentations sensibles ; il possède une raison dont la pure spontanéité produit des idées qui, en dépassant l’expérience, lui assignent des limites. » (Victor Delbos in Kant, Fondements de la métaphysique des mœurs) Et cette raison conduit à une morale déontologique. L’homme n’est pas seulement un phénomène, une chose pour soi ; par le devoir, il est aussi une chose en soi. Le bien n’est pas seulement ce qui, comme le bonheur, se rapporte à la sensibilité. Le bien est ce qui découle de l’application de la loi morale.

Il ne faut pas partir du bien tel qu’il serait conçu esthétiquement, ou au cas par cas, il faut partir de la volonté bonne, celle qui est issue de l’observation de la loi morale, celle qui peut faire l’objet d’une maxime universelle, nonobstant nos inclinations. Ce n’est jamais l’intuition qui peut définir le bien, mais la loi morale universalisable. « La loi morale humilie inévitablement tout homme quand il compare avec cette loi la tendance sensible de sa nature. » (Critique de la raison pratique). Cette volonté bonne choisissant la loi morale est ainsi un jugement synthétique a priori, s’appliquant au savoir-être-moral, au savoir se comporter, et non à la connaissance théorique de ce qui est. Formidable devoir dissocié de la recherche du bonheur. « Devoir ! nom sublime et grand, toi qui ne renfermes rien en toi d'agréable, rien qui implique insinuation, mais qui réclame la soumission, qui cependant ne menace de rien de ce qui éveille dans l'âme une aversion naturelle et l'épouvante pour mettre en mouvement la volonté, mais pose simplement une loi qui trouve d'elle-même accès dans l'âme et qui cependant gagne elle-même malgré nous la vénération (sinon toujours l'obéissance), devant laquelle se taisent tous les penchants, quoiqu'ils agissent contre elle en secret ; quelle origine est digne de toi, et où trouve-t-on la racine de ta noble tige, qui repousse fièrement toute parenté avec les penchants, racine dont il faut faire dériver, comme de son origine, la condition indispensable de la seule valeur que les hommes peuvent se donner eux-mêmes ? » (Critique de la raison pratique, 1ere partie, I, 3).

Il ne faut pas partir du bien tel qu’il serait conçu esthétiquement, ou au cas par cas, il faut partir de la volonté bonne, celle qui est issue de l’observation de la loi morale, celle qui peut faire l’objet d’une maxime universelle, nonobstant nos inclinations. Ce n’est jamais l’intuition qui peut définir le bien, mais la loi morale universalisable. « La loi morale humilie inévitablement tout homme quand il compare avec cette loi la tendance sensible de sa nature. » (Critique de la raison pratique). Cette volonté bonne choisissant la loi morale est ainsi un jugement synthétique a priori, s’appliquant au savoir-être-moral, au savoir se comporter, et non à la connaissance théorique de ce qui est. Formidable devoir dissocié de la recherche du bonheur. « Devoir ! nom sublime et grand, toi qui ne renfermes rien en toi d'agréable, rien qui implique insinuation, mais qui réclame la soumission, qui cependant ne menace de rien de ce qui éveille dans l'âme une aversion naturelle et l'épouvante pour mettre en mouvement la volonté, mais pose simplement une loi qui trouve d'elle-même accès dans l'âme et qui cependant gagne elle-même malgré nous la vénération (sinon toujours l'obéissance), devant laquelle se taisent tous les penchants, quoiqu'ils agissent contre elle en secret ; quelle origine est digne de toi, et où trouve-t-on la racine de ta noble tige, qui repousse fièrement toute parenté avec les penchants, racine dont il faut faire dériver, comme de son origine, la condition indispensable de la seule valeur que les hommes peuvent se donner eux-mêmes ? » (Critique de la raison pratique, 1ere partie, I, 3).

*

Mais d’où vient ce devoir ? Il vient de ce que l’homme s’élève au-dessus de lui-même. Il vient de ce que l’homme est libre par rapport à la nature. Il vient de ce qu’il a une personnalité. C’est en tant qu’il a une personnalité et est homme de devoir que l’homme doit et peut se respecter lui-même. Si je choisis comme noumène (en soi) d’être homme de devoir – et je peux faire ce choix – je serais comme phénomène (pour soi) homme de devoir. Ici, l’essence précède l’existence. L’une entraine l’autre. Il faut remonter en amont des comportements, au moment du choix initial de ce que l’on est, pour les comprendre. Kant pose la liberté comme a priori, avant l’expérience de celle-ci. La liberté appartient ainsi à l’homme nouménal, et non à l’homme phénoménal, celui de l’expérience (ce qui n’empêche évidemment pas la liberté de s’expérimenter). Chez Kant, répétons-le, l’essence précède l’existence. L’homme est donc pleinement responsable de ses actes. Dieu a créé les choses en soi, et l’homme peut faire le choix de la raison, de la volonté bonne, du devoir. Si l’homme ne fait pas ce choix, Dieu n’est pas responsable des phénomènes. L’être créé est chose en soi, mais, dans le temps, dans la temporalité, il se manifeste comme phénomène. Créé par Dieu, l’homme est donc libre. Le cardinal de Bérulle, au début de XVIIe siècle, dit : « Dieu nous a confié nous-mêmes à nous-mêmes ». Si nous pensons dans les termes des Anciens, le devoir est ce qu’ils appelaient la vertu. Mais le devoir engendre-t-il le bonheur ? Ce serait mêler dans un même registre le devoir, qui relève de la raison, et le bonheur, qui relève des réalités sensibles. Pour que le bonheur soit possible, cela nécessite que se rejoignent ces deux ordres, sensibilité et raison. C’est pourquoi Kant nous dit que le bonheur suppose que la vertu, c’est-à-dire la loi morale, puisse nous perfectionner dans le temps. Pour cela, il postule qu’il faudrait, pour avoir ce temps nécessaire, que notre âme soit immortelle. C’est l’immortalité de l’âme qui permet le progrès, qui s’effectue au niveau de l’espèce humaine, et non à l’échelle du seul individu. Or, qu’est-ce qui permet l’immortalité de l’âme, sinon Dieu ? Dieu veille sur les hommes en tant qu’espèce et non sur moi comme simple particulier. De même, comme le bonheur ne peut dépendre que d’un autre que nous, seul Dieu peut nous l’assurer. La croyance en la possibilité du bonheur nécessite donc de croire en l’existence de Dieu. Car Dieu nous a créé non pas être heureux si nous sommes vertueux, mais pour être dignes d’être heureux si nous sommes vertueux. La vertu est une condition nécessaire, mais pas automatique. Dieu nous a enfin créé libres pour nous permettre de choisir d’être moral.

Kant introduit donc comme condition du bonheur trois croyances (l’immortalité de l’âme, l’existence de Dieu, la réalité de notre liberté) mais qui, contrairement a la raison pure théorique, et à la raison pure pratique, ne reposent sur aucune expérience possible. Croyance en Dieu, croyance en l’immortalité de l’âme, croyance en notre état de liberté : nous sommes dans le domaine de la métaphysique, où rien n’est démontrable. Il nous faut donc faire un pari. Surtout, nous constatons que la raison pratique nous a obligé à aller plus loin que la raison pure théorique, puisque nous avons besoin de postuler la vérité de croyances indémontrables car métaphysiques. Ces croyances sont du domaine de la dialectique transcendantale, qui nous permet d’y croire, sans les démontrer. La raison doit donc admettre ces croyances. C’est justement dans la mesure où nous ne connaissons pas les réalités supra-sensibles (Dieu, l’âme, la liberté) que nous agissons par devoir et non par crainte, et c’est ce qui donne sa valeur au devoir comme supérieur aux données sensibles.

Kant introduit donc comme condition du bonheur trois croyances (l’immortalité de l’âme, l’existence de Dieu, la réalité de notre liberté) mais qui, contrairement a la raison pure théorique, et à la raison pure pratique, ne reposent sur aucune expérience possible. Croyance en Dieu, croyance en l’immortalité de l’âme, croyance en notre état de liberté : nous sommes dans le domaine de la métaphysique, où rien n’est démontrable. Il nous faut donc faire un pari. Surtout, nous constatons que la raison pratique nous a obligé à aller plus loin que la raison pure théorique, puisque nous avons besoin de postuler la vérité de croyances indémontrables car métaphysiques. Ces croyances sont du domaine de la dialectique transcendantale, qui nous permet d’y croire, sans les démontrer. La raison doit donc admettre ces croyances. C’est justement dans la mesure où nous ne connaissons pas les réalités supra-sensibles (Dieu, l’âme, la liberté) que nous agissons par devoir et non par crainte, et c’est ce qui donne sa valeur au devoir comme supérieur aux données sensibles.

*

L’une des objections classiques adressées à l’impératif moral catégorique de Kant est celle qui concerne la vérité. A priori, dire la vérité est une loi universellement souhaitable. Il est logique de vouloir en faire une maxime universelle. Mais si un ami est poursuivi par des malfaisants, et que vous savez où il est caché, par exemple chez vous, devez-vous dire la vérité à ceux-ci ? Au risque qu’il soit assassiné ? Même si vous êtes certain qu’il n’a rien à se reprocher ? C’est l’objection à Kant qu’avance Benjamin Constant en 1797 dans Le droit de mentir. Un devoir, nous dit Benjamin Constant, répond à un droit. « Dire la vérité n’est donc un devoir qu’envers ceux qui ont droit à la vérité. » Droit à la vérité veut dire bien entendu droit à connaitre la vérité. Or, il est bien évident que les poursuivants de votre ami sont supposés de n’avoir aucun droit à la vérité. Ce ne sont pas des hommes de justice. Ce sont des criminels. Dans ce cas, ne pas leur dire que votre ami est réfugié chez vous est un « mensonge généreux ». Mais Kant n’admet pas ce raisonnement. Selon lui, dire la vérité ne relève pas d’une intention de nuire à quelqu’un, même dans le cas évoqué. Si cela nuit objectivement à votre ami, la question ne doit pas être posée comme cela. Si cela nuit, c’est l’effet du hasard. On voit que Kant joue sur les mots, puisque dans l’exemple indiqué, il est certain que cela va nuire à votre ami, que vous allez en somme le « dénoncer » en disant la vérité, à savoir qu’il s’est réfugié chez vous.

Cela heurte Benjamin Constant. La vérité ne permet pas d’accorder des droits à l’un et d’en refuser à l’autre, pense-t-il. Selon Constant, dire la vérité n’est nécessaire que si ceux qui la demandent ont droit à la vérité car leurs intentions sont bonnes. Ils n’ont pas droit à la vérité si leurs intentions sont mauvaises. Mais Kant balaie ces arguments – sans même évoquer un autre argument qui serait que l’amitié donne des droits. « Tous les principes juridiquement pratiques doivent renfermer des vérités rigoureuses, et ceux qu’on appelle ici des principes intermédiaires ne peuvent que déterminer d’une manière plus précise leur application aux cas qui se présentent (…), mais ils ne peuvent jamais y apporter d’exceptions, car elles détruiraient l’universalité à laquelle seule ils doivent leur nom de principes. », soutient Kant (« Doctrine de la vertu » in Métaphysique des mœurs, 1795). Il ne peut donc y avoir d’exceptions à l’impératif catégorique universalisable, ce qui implique que tout le monde soit postulé de bonne foi et de bonne volonté.

Cela heurte Benjamin Constant. La vérité ne permet pas d’accorder des droits à l’un et d’en refuser à l’autre, pense-t-il. Selon Constant, dire la vérité n’est nécessaire que si ceux qui la demandent ont droit à la vérité car leurs intentions sont bonnes. Ils n’ont pas droit à la vérité si leurs intentions sont mauvaises. Mais Kant balaie ces arguments – sans même évoquer un autre argument qui serait que l’amitié donne des droits. « Tous les principes juridiquement pratiques doivent renfermer des vérités rigoureuses, et ceux qu’on appelle ici des principes intermédiaires ne peuvent que déterminer d’une manière plus précise leur application aux cas qui se présentent (…), mais ils ne peuvent jamais y apporter d’exceptions, car elles détruiraient l’universalité à laquelle seule ils doivent leur nom de principes. », soutient Kant (« Doctrine de la vertu » in Métaphysique des mœurs, 1795). Il ne peut donc y avoir d’exceptions à l’impératif catégorique universalisable, ce qui implique que tout le monde soit postulé de bonne foi et de bonne volonté.

Autre exemple qui met la morale de Kant en difficulté. Dans L’Existentialisme est un humanisme, Sartre évoque (page 41 et s. de l’édition Folio-essais Gallimard de 1996) une contradiction que l’impératif catégorique du devoir universalisable ne permet pas non plus de résoudre, pas plus que l’impératif complémentaire consistant à ne pas prendre autrui comme moyen. Un jeune homme, pendant la guerre de 39-45, hésite entre rester auprès de sa mère fragile dont il est le seul soutien, ou bien s’engager dans la Résistance. Rester auprès des siens quand ils ont besoin de vous est un devoir universalisable. Lutter contre une tyrannie et une occupation étrangère est aussi un devoir universalisable. Quelle est la solution kantienne ? Il n’y en a pas. Chacun ne peut suivre que sa propre pente. C’est l’application de la formule « c’était plus fort que moi », qui ne fait que justifier a posteriori un choix. Soit on interprète sa vie personnelle et celle de ses proches comme subordonnée à des impératifs plus généraux (la libération de la patrie), soit, à l’inverse, on interprète l’obligation de soutien à ses proches comme déterminante. Cela renvoie à la façon dont on considère l’Occupation de son pays par l’Allemagne en 1940-44. La considère-t-on comme un mal absolu ? Ou comme un mal relatif, et par ailleurs passager, voire comme un mal moins important qu’une libération qui amènerait une autre tyrannie ? Ou qu’une libération chaotique du pays, entrainant des injustices pires que l’Occupation ? Il n’y a en fait pas de réponse morale à cette question. Tout est défendable, d’autant que le hasard se mêle à cela. Je peux entrer dans la Résistance et délaisser ma mère mais être tellement maladroit que je suis plutôt un fardeau qu’une aide pour la Résistance. Je peux rester avec ma mère pour m’occuper d’elle, mais la décevoir et même la désespérer, car je n’ai pas fait le choix du courage civique et patriotique qu’elle attendait de moi, etc. C’est l’hétérotélie. La discussion rationnelle est sans fin, et n’offre aucune solution. Il y a ainsi des limites au caractère efficace de la morale déontologique de Kant – ce qui ne surprendra guère car le critère de Kant n’est pas l’efficacité. Il faut combiner l’analyse kantienne avec une analyse conséquentialiste, comme le voyait Benjamin Constant. On peut aussi, en sortant totalement des conceptions de Kant, faire intervenir un critère esthétique. Ce qui a le plus d’allure est sans doute d’entrer dans la Résistance, à condition que cela ne soit pas au dernier moment, mais ne se préoccuper nullement du sort de sa mère n’est pas très beau. Pour autant, jouer le garde-malade est-il très valorisant au plan esthétique ? La réponse est bien évidemment négative. Alors, à quelle morale se référer ? ll faut d’abord noter la présence actuelle dans le champ de la morale du relativisme et de l’individualisme absolu. C’est la morale relativiste. Elle consiste à dire « A chacun sa morale ». L’individu se voit comme n’ayant pas de devoirs envers la société. Pas de devoir non plus envers une quelconque transcendance (Dieu ou le sacré), ni envers une lignée familiale ou une communauté. La morale est réduite à ses intérêts ou à ses désirs individuels. C’est en fait le contraire d’une morale. C’est aussi le contraire de la morale d’Aristote. On peut considérer celle-ci comme l’autre grand système à côté de celui de Kant.

La morale d’Aristote est une morale du juste milieu, c’est-à-dire non pas de la moyenne médiocrité des choses, mais de la juste appréciation. Disons même : une morale du juste discernement des situations. Une morale de la circonspection. C’est une morale du style, de l’allure : faire ce qui est noble et digne. Elle inclut certes en partie la morale kantienne : il n’est, par exemple, pas beau de mentir car, si tout le monde mentait, c’est la laideur morale qui serait universalisée. Mais elle inclut aussi le point de vue conséquentialiste. Il est encore moins beau de dire la vérité que de mentir quand dire la vérité est trahir un ami. Et ce point de vie conséquentialiste est plus encore esthétique. Kant avait noté le lien étroit entre le bien et le beau (Observation sur le sentiment du beau et du sublime, 1764). Il rejoignait ici Aristote. Mais pourtant, il élaborait quelques années plus tard une morale bien loin de celle d’Aristote.

La morale d’Aristote est une morale du juste milieu, c’est-à-dire non pas de la moyenne médiocrité des choses, mais de la juste appréciation. Disons même : une morale du juste discernement des situations. Une morale de la circonspection. C’est une morale du style, de l’allure : faire ce qui est noble et digne. Elle inclut certes en partie la morale kantienne : il n’est, par exemple, pas beau de mentir car, si tout le monde mentait, c’est la laideur morale qui serait universalisée. Mais elle inclut aussi le point de vue conséquentialiste. Il est encore moins beau de dire la vérité que de mentir quand dire la vérité est trahir un ami. Et ce point de vie conséquentialiste est plus encore esthétique. Kant avait noté le lien étroit entre le bien et le beau (Observation sur le sentiment du beau et du sublime, 1764). Il rejoignait ici Aristote. Mais pourtant, il élaborait quelques années plus tard une morale bien loin de celle d’Aristote.

La raison et la parole (le logos) sont, nous dit Aristote, le propre de l’homme. Ils nous conduisent à vouloir le bien pour nous-mêmes, c’est-à-dire à vouloir notre bonheur, mais ce nous concerne aussi le bonheur de la cité. Dans le domaine pratique, le bien est soit la fabrication (poiesis), soit l’action elle-même (praxis). Cette dernière est avant tout l’action politique. C’est une action qui ne vise pas la fabrication d’un objet. C’est une pratique qui vise à se gouverner et à gouverner la cité. A bien la gouverner. L’action politique doit se soucier du bien commun et des conditions de la vie bonne. Elle nécessite la prudence (phronésis), et la recherche de la justesse, qui n’est pas la moyenne entre deux extrêmes, mais une ligne de crête entre deux maux, par exemple entre la témérité et la lâcheté. L’homme doit bien faire ce qu’il sait faire, bien jouer de la musique s’il sait jouer de la musique, bien faire du pain s’il est boulanger, etc. « (…) nous supposons que le propre de l’homme est un certain genre de vie, que ce genre de vie est l’activité de l’âme, accompagnée d’actions raisonnables, et que chez l’homme accompli tout se fait selon le Bien et le Beau, chacun de ses actes s’exécutant à la perfection selon la vertu qui lui est propre. A ces conditions, le bien propre à l’homme est l’activité de l’âme, en conformité avec la vertu ; et si les vertus sont nombreuses, selon celle qui est la meilleure et la plus accomplie. » (Ethique à Nicomaque, I, 7, trad. Jean Voilquin, Garnier, 1961). Le bonheur correspond à la vertu la plus haute, qui est la connaissance. Celle-ci est la sagesse même. « (…) le bonheur n’a d’autres limites que celles de la contemplation. Plus notre faculté de contempler se développe, plus se développent nos possibilités de bonheur et cela, non par accident, mais en vertu même de la nature de la contemplation. Celle-ci est précieuse par elle-même, si bien que le bonheur, pourrait-on dire, est une espèce de contemplation. » (Ethique à Nicomaque, X, 7 et 9). Le bonheur ne consiste donc pas dans ce que l’on produit, dans ce que l’on fait (poiesis), mais dans ce que l’on voit (voir et connaitre, c’est la même chose pour les Grecs), le monde et la sagesse, le monde et sa sagesse. Dans cet exercice des activités vertueuses, les plaisirs liés à l’activité, y compris de contemplation, sont toutefois un encouragement bienvenu. Car la persévérance est nécessaire à la vertu. « (…) ce qu’il faut apprendre pour le faire, nous l’apprenons en le faisant : par exemple, c’est en bâtissant qu’on devient architecte ; en jouant de la cithare qu’on devient citharède. De même, c’est à force de pratiquer la justice, la tempérance et le courage que nous devenons justes, tempérants et courageux. » (Ethique à Nicomaque, II, 7). La question n’est donc non pas d’appliquer une règle universelle (Kant), mais de devenir soi-même meilleur, de viser la juste ligne de crête.

PLV

A propos de l’auteur :

Pierre Le Vigan est urbaniste de formation et essayiste.

Derniers ouvrages parus : Avez-vous compris les philosophes ? I à V. Introduction à l’œuvre de 42 philosophes, La Barque d’or, diffusion amazon, 512 pages, 24,99 € (en promotion à 12 € en ce moment), Eparpillé façon puzzle. Macron contre le peuple et les libertés, Perspectives Libres, 2022, diffusion Cercle Aristote, Le grand empêchement (Comment le libéralisme entrave les peuples), Perspectives libres, 2021, Métamorphoses de la ville. De Romulus à Le Corbusier, La Barque d’Or, 2022 (diffusion amazon)

* * *

Pierre Le Vigan est urbaniste et essayiste. L'auteur travaille dans le domaine du logement social. En parallèle, depuis plus de 30 ans, il a écrit dans de nombreuses revues (Perspectives Libres, la Nouvelle Revue d'Histoire, Eléments, Nouvelle Ecole, Krisis, le Spectacle du Monde, la Nouvelle Revue Universelle...), dans des revues électroniques (Philitt, livr’ arbitre, contrelittérature, …), et dans des revues de phénoménologie.

Spécialiste de l'histoire des idées (articles sur Clément Rosset, Friedrich Nietzsche, Martin Heidegger, Françoise Dastur, Alain de Benoist, Rémi Brague, Pierre Manent, Alain Caillé, Serge Latouche, ...), il a publié aussi des textes sur la phénoménologie et la psychologie (voir son ouvrage Le malaise est dans l'homme et Face à l'addiction). Ses écrits ont aussi porté sur Jean Prévost, Jean Giono, George Orwell, Albert Camus, Walter Benjamin, ... Il s'est aussi intéressé au cinéma, à la peinture, la sexualité, la politique, la cosmologie.

Un portrait de l'essayiste est paru dans Le Spectacle du monde, sous la plume de François-Laurent Balssa en janvier 2012 (''Pierre Le Vigan, un urbaniste chez les philosophes"). L'auteur a développé une critique du capitalisme comme réification de l'homme, un refus de l'idéologie productiviste, du culte de la croissance, de l'idéologie du progrès, de la destruction des peuples et des cultures aussi bien par l'uniformisation marchande que par la transplantation des populations. Le revers du mondialisme est selon lui le communautarisme (revue Perspectives libres, 15, 2015) qui est une perversion de l'enracinement.

Un entretien avec l'auteur et un portrait sont parus dans L'Incorrect en octobre 2020 : Pierre Le Vigan : « Les post soixante-huitards sont passés du nihilisme passif au nihilisme actif. ».

Des Carnets politiques, littéraires, philosophiques de l'auteur ont été regroupés dans Le Front du Cachalot (2009), préfacé par Michel Marmin. Le titre qui fait référence à Moby Dick d'Herman Melville. D'autres carnets se trouvent dans La Tyrannie de la transparence, Chronique des temps modernes, Soudain la postmodernité. Pierre Le Vigan a aussi parfois utilisé les pseudonymes de Noël Rivière et de Fabrice Mistral (Krisis, n° Psychologie).

L'auteur s'exprime dans divers médias (TV Libertés, Sputnik, Boulevard Voltaire, Radio courtoisie, Cercle Aristote...).

Urbaniste de formation (DESS de l'Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, DEA de l'EHESS et CEA d'Ecole d'Architecture), il a aussi obtenu une maîtrise d'Administration Economique et Sociale, une licence d'histoire (Université Paris 1), un DESU de psychopathologie (Paris VIII Saint Denis. Mention Trés bien), une licence de philosophie (Institut catholique de Paris. mention Bien).

Pour trouver le site de l'auteur, taper : la barque d'or avec pierre le vigan

http://la-barque-d-or.centerblog.net/

contact éditeur : labarquedor@gmail.com

Ouvrages :

- Inventaire de la modernité, avant liquidation : au-delà de la droite et de la gauche : études sur la société, la ville, la politique (préf. Alain de Benoist), Avatar, « Polémiques », 2007 (ISBN 978095551325) SUDOC 130699098. réédité par La Barque d'Or

- La Patrie, l'Europe et le Monde : éléments pour un début sur l'identité des Européens (dir. avec Jacques Marlaud), Dualpha, 2009 (SUDOC 133242161).

- Le Front du Cachalot : carnets de fureur et de jubilation (préf. Michel Marmin), Dualpha, 2009. ISBN 9782353741366 rééditié par la barque d'or

- La Tyrannie de la transparence : carnets II (préf. Arnaud Guyot-Jeannin), L'Aencre-Dualpha, 2011 ISBN 9782353741366 (SUDOC 157765989). rééditié par la barque d'or

- Le malaise est dans l'homme : psychopathologie et souffrances psychiques de l'homme moderne (préf. Thibault Isabel), Avatar, 2011. ISBN 978-1907847059 rééditié par la barque d'or

- La Banlieue contre la ville : comment la banlieue dévore la ville, La Barque d'Or, 2011, ISBN 978-2-9539387-0-8, notice BnF n°FRBNF42539340.

- Écrire contre la modernité, La Barque d'Or, 2012, ISBN 978-2-9539387-1-5, notice BnF no FRBNF42700054.

- Chronique des temps modernes, La Barque d'Or, 2014, ISBN 978-2-9539387-2-2, notice BnF no FRBNF43756341.

- L'Effacement du politique : philosophie politique et genèse de l'impuissance politique de l'Europe (préf. Éric Maulin), La Barque d'Or, 2014, ISBN 978-2-9539387-3-9, notice BnF no FRBNF43807908.

- Soudain la postmodernité : de la dévastation certaine d'un monde au possible surgissement du neuf (préf. Christian Brosio), La Barque d'Or, 2015, ISBN 978-2-9539387-4-6, notice BnF no FR-BNF44339206.

- Métamorphoses de la ville, de Romulus à Le Corbusier, La Barque d'Or, septembre 2017, ISBN 978-2-9539387-6-0, notice BNF N° FRBNF45464513

- Face à l'addiction, La Barque d'Or, février 2018, ISBN 978-2-9539387-8-4, notice BNF N° FRBNF45460554

- Achever le nihilisme. Figures, manifestations, théories et perspectives, Sigest, février 2019. ISBN 9782376040224.

- Avez-vous compris les philosophes ? Platon, Aristote, Descartes, Kant, Hegel, Nietzsche, Heidegger, postlude Empédocle, La Barque d'Or, avril 2019, ISBN 978-2-9539387-5-3

- Le Grand Empêchement. Comment le libéralisme entrave les peuples, Ed. Perspectives Libres, Novembre 2019. ISBN 9791090742512

- Avez-vous compris les philosophes ? II, Spinoza, Fichte, Schelling, Bergson, Sartre, Foucault, La Barque d'Or, janvier 2020 : ISBN 978-2-491020-00-2.

- Avez-vous compris les philosophes ? III, Epicure, Lucrèce, Berkeley, Hume, Bruno, Lénine, Ortega. Sur Platon. Sur Maffesoli, La Barque d'Or, mai 2020. ISBN 978-2-491020-01-9

- Avez-vous compris les philosophes ? IV Hobbes, Locke, Leibniz, Dilthey, Rosset. La Barque d'or janvier 2021, ISBN 978-2-491020-03-3

- Comprendre les philosophes. Préface de Michel Maffesoli, Dualpha, 2021. ISBN 9782353745418

- Nietzsche et l'Europe suivi de Nietzsche et Heidegger face au nihilisme, Perspectives Libres, 2022. ISBN 979-10-90742-67-3

- Eparpillé façon puzzle (Un peuple en miettes). La politique de Macron contre le peuple et les libertés, Entretien sur le libéralisme, Perspectives Libres, 2022, ISBN 979-10-90742-68-0

- La planète des philosophes. Comprendre les philosophes II. Préface d'Alain de Benoist. Dualpha, janvier 2023. ISBN 978-23-53746-07-1

- Avez-vous compris les philosophes ? V. Thalès de Milet, Anaximandre, Anaximène, Pythagore, Héraclite, Parménide, Anaxagore, Empédocle, Démocrite, Augustin, Scot Erigène, Abélard, Ockham, Malebranche, La Mettrie, Holbach suivi Les limites de la morale de Kant. La Barque d'or, mai 2023. ISBN 978-2491020040

- Avez-vous compris les philosophes ? I à V. Une introduction à l'oeuvre de 42 philosophes ? La Barque d'Or, novembre 2023, ISBN 978-2-491020-05-7

Courriel des éditions ''la barque d'or'': la barquedor@gmail.com

SITE : la-barque-d-or.centerblog.net/

pour trouver le site : "la barque d'or avec pierre le vigan"

Contributions :

- Le Mai 68 de la Nouvelle Droite, Paris, Éditions du Labyrinthe, 1998.

- Arnaud Guyot-Jeannin (éd.), Aux sources de l'erreur libérale, pour sortir de l'étatisme et du libéralisme, L'Âge d'Homme, 1999.

- Arnaud Guyot-Jeannin (éd.), Aux sources de la droite, pour en finir avec les clichés, L'Âge d'Homme, 2000.

- Michel Marmin (éd.), Liber Amicorum Alain de Benoist, Paris, Les Amis d’Alain de Benoist, 2004.

- Face à la crise, une autre Europe, Synthèse nationale, 2012.

- Thibault Isabel (éd.), Liber Amicorum Alain de Benoist II, Paris, Les Amis d’Alain de Benoist, 2013.

- Article "Hegel" dans Pourquoi combattre ? sous la direction de Pierre-Yves Rougeyron, éd. Perspectives Libres, 2019.

Préfaces :

- Patrick Brunot, Arrêt sur lectures, Dualpha, 2010.

- Philippe Randa, Sous haute surveillance politique, Dualpha, 2011.

- Georges Feltin-Tracol, L'esprit européen entre mémoires locales et volonté continentale, Héligoland, 2011.

- Arnaud Guyot-Jeannin, L'avant-garde de la tradition dans la culture, Pierre-Guillaume de Roux, 2016 (notice BnF no FRBNF45174598).

- Nicolas Bonnal, Le choc Macron. Les antisystèmes sont-ils nuls ? 2017 (ISBN-13: 978-1521364413).

- Aristide Leucate, Dictionnaire du désastre français et européen, Dualpha, 2018 (ISBN-13: 978-2353743780).

11:57 Publié dans Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : emmanuel kant, immanuel kant, pierre le vigan, philosophie, morale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 13 mai 2023

Quand Emmanuel Kant dénonce la dette et le colonialisme occidental…

Quand Emmanuel Kant dénonce la dette et le colonialisme occidental…

par Nicolas Bonnal

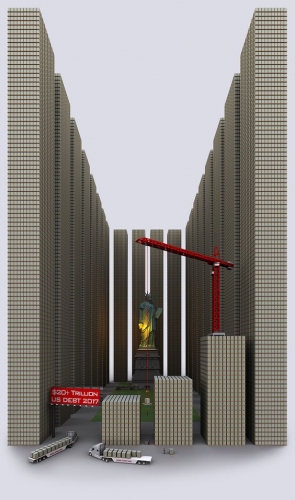

Projet de paix perpétuelle : un texte célèbre et mal lu. Car le plus grand esprit du siècle tord le cou aux Occidentaux : voyons ce qu’il dit de la dette (qui en Occident signifie la richesse de la nation, plaisante Marx dans le Capital, VI) :

« Chercher des ressources au dedans ou au dehors dans l’intérêt de l’économie du pays (pour l’amélioration des routes, la fondation de nouvelles colonies, l’établissement de magasins pour les années stériles, etc.) ne présente rien de suspect. »

Mais la menace arrive avec l’Angleterre, qui bâtit son empire et ses guerres napoléoniennes avec sa dette immonde ; Kant s’inquiète :

« Mais il n’en est pas de même de ce système de crédit, — invention ingénieuse d’une nation commerçante de ce siècle, — où les dettes croissent indéfiniment, sans qu’on soit jamais embarrassé du remboursement actuel (parce que les créanciers ne l’exigent pas tous à la fois) : comme moyen d’action d’un État sur les autres, c’est une puissance pécuniaire dangereuse ; c’est en effet un trésor tout prêt pour la guerre, qui surpasse les trésors de tous les autres États ensemble et ne peut être épuisé que par la chute des taxes, dont il est menacé dans l’avenir (mais qui peut être retardée longtemps encore par la prospérité du commerce et la réaction qu’elle exerce sur l’industrie et le gain). »

Qui dit dette dit en effet guerre, et une guerre éternelle comme celle menée par les pays anglo-saxons :

« Cette facilité de faire la guerre, jointe au penchant qui y pousse les souverains et qui semble inhérent à la nature humaine, est donc un grand obstacle à la paix perpétuelle… »

La paix perpétuelle ne peut se faire que sans l’Occident : on le sait maintenant. Un total écroulement financier et économique de ce tordu pourra seul établir la paix dans le monde. Voilà pour la dette.

Et puis Kant pousse plus loin : il se rend compte des mauvaises manières (on ne dit pas encore coloniales) des Occidentaux. Et cela donne :

« Si maintenant on examine la conduite inhospitalière des États de l’Europe, particulièrement des États commerçants, on est épouvanté de l’injustice qu’ils montrent dans leur visite aux pays et aux peuples étrangers (visite qui est pour eux synonyme de conquête). L'Amérique, les pays habités par les nègres, les îles des épiceries, le Cap, etc., furent, pour ceux qui les découvrirent, des pays qui n'appartenaient à personne, car ils comptaient les habitants pour rien. »

Kant dénonce le désordre et le chaos amené partout par les « civilisateurs occidentaux » :

« Dans les Indes orientales (dans l’Indoustan), sous prétexte de n'établir que des comptoirs de commerce, les Européens introduisirent des troupes étrangères, et par leur moyen opprimèrent les indigènes, allumèrent des guerres entre les différents États de cette vaste contrée, et y répandirent la famine, la rébellion, la perfidie et tout le déluge des maux qui peuvent affliger l’humanité. »

Après des pays plus lointains et plus puissants se méfient – et comme on les comprend :

« La Chine et le Japon, ayant fait l’essai de pareils hôtes, leur refusèrent sagement, sinon l’accès, du moins l'entrée de leur pays ; ils n’accordèrent même cet accès qu’à un seul peuple de l’Europe, aux Hollandais, et encore en leur interdisant, comme à des captifs, toute société avec les indigènes. »

Mais la Chine sera économiquement anéantie au siècle suivant (perdant 90% de sa capacité productive grâce toujours à la civilisatrice Angleterre qui affame l’Inde) et le Japon finira en 1945 comme on sait après avoir mal copié l’Occident et avoir été poussé à faire la guerre à la Russie en 1905.

Et Kant note le caractère dérisoire de ce développement à l’occidentale :

« Le pire (ou, pour juger les choses au point de vue de la morale, le mieux), c'est que l’on ne jouit pas de toutes ces violences, que toutes les sociétés de commerce qui les commettent touchent au moment de leur ruine, que les îles à sucre, ce repaire de l'esclavage le plus cruel et le plus raffiné, ne produisent pas de revenu réel et ne profitent qu’indirectement, ne servant d'ailleurs qu’à des vues peu louables, c’est-à-dire à former des matelots pour les flottes et à entretenir ainsi des guerres en Europe, et cela entre les mains des États qui se piquent le plus de dévotion et qui, en s’abreuvant d’iniquités, veulent passer pour des élus en fait d'orthodoxie. »

On note au passage l’allusion à la tartuferie occidentale. Comme dira Trotski dans un texte célèbre que j’ai recensé :

« L’histoire favorise le capital américain: pour chaque brigandage, elle lui sert un mot d’ordre d’émancipation. »

Eh bien c’est enfin en train de se terminer.

Sources :

https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/M%C3%A9taphysique_des_m%C5...

https://blogs.mediapart.fr/danyves/blog/220117/comment-tr...

11:20 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : immanuel kant, dette, philosophie, colonialisme, occident |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 20 mai 2013

The Enlightenment from a New Right Perspective

The Enlightenment from a New Right Perspective

By Domitius Corbulo

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

“When Kant philosophizes, say on ethical ideas, he maintains the validity of his theses for men of all times and places. He does not say this in so many words, for, for himself and his readers, it is something that goes without saying. In his aesthetics he formulates the principles, not of Phidias’s art, of Rembrandt’s art, but of Art generally. But what he poses as necessary forms of thought are in reality only necessary forms of Western thought.” — Oswald Spengler

“Humanity exists in its greatest perfection in the white race.” — Immanuel Kant

Every one either praises or blames the Enlightenment for the enshrinement of equality and cosmopolitanism as the moral pillars of our times. This is wrong. Enlightenment thinkers were racists who believe that only white Europeans could be fully rational, good citizens, and true cosmopolitans.

Leftists have brought attention to some racist beliefs among Enlightenment thinkers, but they have not successfully shown that racism was an integral part of Enlightenment philosophy, and their intention has been to denigrate the Enlightenment for representing the parochial values of European males. I argue here that they were the first to introduce a scientific conception of human nature structured by racial classifications. This conception culminated in Immanuel Kant’s anthropological justification of the superior/inferior classification of “races of men” and his “critical” argument that only European peoples were capable of becoming rational and free legislators of their own actions. The Enlightenment is a celebration of white reason and morality; therefore, it belongs to the New Right.

In an essay [2] in the New York Times (February 10, 2013), Justin Smith, another leftist with a grand title, Professeur des Universités, Département d’Histoire et Philosophie des Sciences, Université Paris Diderot – Paris VII, contrasted the intellectual “legacy” of Anton Wilhelm Amo, a West African student and former slave who defended a philosophy dissertation at the University of Halle in Saxony in 1734, with the “fundamentally racist” legacy of Enlightenment thinkers. Smith observed that a dedicatory letter was attached to Amo’s dissertation from the rector of the University of Wittenberg, Johannes Kraus, praising the “natural genius” of Africa and its “inestimable contribution to the knowledge of human affairs.” Smith juxtaposed Kraus’s broad-mindedness to the prevailing Enlightenment view “lazily echoed by Hume, Kant, and so many contemporaries” according to which Africans were naturally inferior to whites and beyond the pale of modernity.

Smith questioned “the supposedly universal aspiration to liberty, equality and fraternity” of Enlightenment thought. These values were “only ever conceived” for a European people deemed to be superior and therefore more equal than non-whites. He cited Hume: “I am apt to suspect the Negroes, and in general all other species of men to be naturally inferior to the whites.” He also cited Kant’s dismissal of a report of something intelligent that had once been uttered by an African: “this fellow was quite black from head to toe, a clear proof that what he said was stupid.” Smith asserted that it was counter-Enlightenment thinkers, such as Johann Herder, who would formulate anti-racist views in favor of human diversity. In the rest of his essay, Smith pondered why Westerners today “have chosen to stick with categories inherited from the century of the so-called Enlightenment” even though “since the mid-20th century no mainstream scientist has considered race a biologically significant category; no scientist believes any longer that ‘negroid,’ ‘caucasoid,’ and so on represent real natural kinds.” We should stop using labels that merely capture “something as trivial as skin color” and instead appreciate the legacy of Amo as much as that of any other European in a colorblind manner.

Smith’s article, which brought some 370 comments, a number from Steve Sailer, was challenged a few days later by Kenan Malik, ardent defender of the Enlightenment, in his blog Pandaemonium [3]. Malik’s argument that Enlightenment thinkers “were largely hostile to the idea of racial categorization” represents the general consensus on this question. Malik is an Indian-born English citizen, regular broadcaster at BBC, and noted writer for The Guardian, Financial Times, The Independent, Sunday Times, New Statesman, Prospect, TLS, The Times Higher Education Supplement, and other venues. Once a Marxist, Malik is today a firm defender of the “universalist ideas of the Enlightenment,” freedom of speech, secularism, and scientific rationalism. He is best known for his strong opposition to multiculturalism.

Yet this staunch opponent of multiculturalism is a stauncher advocate of open door policies on immigration [4]. In one of his TV documentaries, tellingly titled Let ‘Em All In (2005), he demanded that Britain’s borders be opened to the world without restrictions. In response to a report published during the post-Olympic euphoria in Britain, “The Melting Pot Generation: How Britain became more relaxed about race [5],” he wrote: “news that those of mixed ethnicity are among the fastest-growing groups in the population is clearly to be welcomed [6].” He added that much work remains to be done “to change social perceptions of race.”

This work includes fighting against any immigration objection even from someone like David Goodhart, director of the left think tank Demos, whose just released book, The British Dream [7], modestly made the observation that immigration is eroding traditional identities and creating an England “increasingly full of mysterious and unfamiliar worlds.” In his review (The Independent [8], April 19, 2013) Malik insisted that not enough was being done to wear down the traditional identities of everyone including the native British. The solution is more immigration coupled with acculturation to the universal values of the Enlightenment. “I am hostile to multiculturalism not because I worry about immigration but because I welcome it.” The citizens of Britain must be asked to give up their ethnic and cultural individuality and make themselves into universal beings with rights equal to every newcomer.

It is essential, then, for Malik to disassociate the Enlightenment with any racist undertones. This may not seem difficult since the Enlightenment has consistently come to be seen — by all political ideologies from Left to Right — as the source of freedom, equality, and rationality against the “unreasonable and unnatural” prejudices of particular cultural groups. Malik acknowledges that in recent years some (he mentions George Mosse, Emmanuel Chuckwude Eze, and David Theo Goldberg) have blamed Enlightenment thinkers for articulating the modern idea of race and projecting a view of Europe as both culturally and racially superior. By and large, however, Malik manages (superficially speaking) to win the day arguing that the racist statements one encounters in some Enlightenment thinkers were marginally related to their overall philosophies.

A number of thinkers within the mainstream of the Enlightenment . . . dabbled with ideas of innate differences between human groups . . . Yet, with one or two exceptions, they did so only diffidently or in passing.

The botanist Carolus Linnaeus exhibited the cultural prejudices of his time when he described Europeans as “serious, very smart, inventive” and Africans as “impassive, lazy, ruled by caprice.” But let’s us not forget, Malik reasons, that Linnaeus’ Systema Naturae “is one of the landmarks of scientific thought,” the first “distinctly modern” classification of plants and animals, and of humans in rational and empirical terms as part of the natural order. The implication is that Linnaeus could not have offered a scientific classification of nature while seriously believing in racial differences. Science and race are incompatible.

Soon the more progressive ideas of Johann Blumenbach came; he complained about the prejudices of Linnaeus’ categories and called for a more objective differentiation between human groups based on skull shape and size. It is true that out of Blumenbach’s five-fold taxonomy (Caucasians, Mongolians, Ethiopians, Americans and Malays) the categories of race later emerged. But Malik insists that “it was in the 19th, not 18th, century that a racial view of the world took hold in Europe.”

Malik mentions Jonathan Israel’s argument that there were two Enlightenments, a mainstream one coming from Kant, Locke, Voltaire and Hume, and a radical one coming from “lesser known figures such as d’Holbach, Diderot, Condorcet and Spinoza.” This latter group pushed the ideas of reason, universality, and democracy “to their logical conclusion,” nurturing a radical egalitarianism extending across class, gender, and race. But, in a rather confusing way and possibly because he could not find any discussions of race in the radical group to back up his argument, Malik relies on the mainstream group. He cites David Hume: “It is universally acknowledged that there is a great uniformity among the acts of men, in all nations and ages, and that human nature remains the same in its principles and operations.” And George-Louis Buffon, the French naturalist: “Every circumstance concurs in proving that mankind is not composed of species essentially different from each other.” While Enlightenment thinkers asked why there was so much cultural variety across the globe, Malik explains, “the answer was rarely that human groups were racially distinct . . . environmental differences and accidents of history had shaped societies in different ways.” Remedying these differences and contingencies was what the Enlightenment was about; as Diderot wrote, “everywhere a people should be educated, free, and virtuous.”

Malik’s essay is pedestrian, somewhat disorganized, but in tune with the established literature, and therefore seen by the public as a compilation of truisms against marginal complaints about racism in the Enlightenment. Almost all the books on the Enlightenment have either ignored this issue or addressed it as a peripheral theme. The emphasis has been, rather, on the Enlightenment’s promotion of universal values for the peoples of the world. Let me offer some examples. Leonard Krieger’s King and Philosopher, 1689–1789 (1970) highlights the way the Enlightenment produced “works in which the universal principles of reason were invoked to order vast reaches of the human experience,” Rousseau’s “anthropological history of the human species,” Hume’s “quest for uniform principles of human nature,” “the various tendencies of the philosophes’ thinking — skepticism, rationalism, humanism, and materialism” (152-207). Peter Gay’s The Enlightenment: An Interpretation (1966) is altogether about how “the men of the Enlightenment united on . . . a program of secularism, humanity, cosmopolitanism, and freedom . . . In 1784, when the Enlightenment had done most of its work, Kant defined it as man’s emergence from his self-imposed tutelage, and offered as its motto: Dare to know” (3). Norman Hampson’s The Enlightenment (1968) spends more time on the proponents of modern classifications of nature, particularly Buffon’s Natural History, but makes no mention of racial classifications or arguments opposing any notion of a common humanity.

Recent books are hardly different. Louis Dupre’s The Enlightenment and the Intellectual Foundations of Modern Culture (2004), traces our current critically progressive attitudes back to the Enlightenment “ideal of human emancipation.” Dupré argues (from a perspective influenced by Jurgen Habermas) that the original project of the Enlightenment is linked to “emancipatory action” today (335). Gertrude Himmelfarb’s The Roads to Modernity: The British, French, and American Enlightenments (2004), offers a neoconservative perspective of the British and the American “Enlightenments” contrasted to the more radical ideas of human perfectibility and the equality of mankind found in the French philosophes. She brings up Jefferson’s hope that in the future whites would “blend together, intermix” and become one people with the Indians (221). She quotes Madison on the “unnatural traffic” of slavery and its possible termination, and also Jefferson’s proposal that the slaves should be freed and sent abroad to colonize other lands as “free and independent people.” She implies that Jefferson thought that sending blacks abroad was the most humane solution given the “deep-rooted prejudices of whites and the memories of blacks of the injuries they had sustained” (224).

Recent books are hardly different. Louis Dupre’s The Enlightenment and the Intellectual Foundations of Modern Culture (2004), traces our current critically progressive attitudes back to the Enlightenment “ideal of human emancipation.” Dupré argues (from a perspective influenced by Jurgen Habermas) that the original project of the Enlightenment is linked to “emancipatory action” today (335). Gertrude Himmelfarb’s The Roads to Modernity: The British, French, and American Enlightenments (2004), offers a neoconservative perspective of the British and the American “Enlightenments” contrasted to the more radical ideas of human perfectibility and the equality of mankind found in the French philosophes. She brings up Jefferson’s hope that in the future whites would “blend together, intermix” and become one people with the Indians (221). She quotes Madison on the “unnatural traffic” of slavery and its possible termination, and also Jefferson’s proposal that the slaves should be freed and sent abroad to colonize other lands as “free and independent people.” She implies that Jefferson thought that sending blacks abroad was the most humane solution given the “deep-rooted prejudices of whites and the memories of blacks of the injuries they had sustained” (224).

Dorinda Outram’s, The Enlightenment (1995) brings up directly the way Enlightenment thinkers responded to their encounters with very different cultures in an age characterized by extraordinary expeditions throughout the globe. She notes there “was no consensus in the Enlightenment on the definition of the races of man,” but, in a rather conjectural manner, maintains that “the idea of a universal human subject . . . could not be reconciled with seeing Negroes as inferior.” Buffon, we are safely informed, “argued that the human race was a unity.” Linnaeus divided humanity into different classificatory groups, but did so as members of the same human race, although he “was unsure whether pigmies qualified for membership of the human race.” Turgot and Condorcet believed that “human beings, by virtue of their common humanity, would all possess reason, and would gradually discard irrational superstitions” (55-8). Outram’s conclusion on this topic is typical: “The Enlightenment was trying to conceive a universal human subject, one possessed of rationality,” accordingly, it cannot be seen as a movement that stood against racial divisions (74). Roy Porter, in his exhaustively documented and opulent narrative, Enlightenment: Britain and the Creation of the Modern World (2000), dedicates less than one page of his 600+ page book to discourses on “racial differentiation.” He mentions Lord Kames as “one of many who wrestled with the evidence of human variety . . . hinting that blacks might be related to orang-utans and similar great apes.” Apart from this quaint passage, there is only this: “debate was heated and unresolved, and there was no single Enlightenment party line” (357).

In my essay, “Enlightenment and Global History [9],” I mentioned a number of other books which view the Enlightenment as a European phenomenon and, for this reason, have been the subject of criticism by current multicultural historians who feel that this movement needs to be seen as global in origins. I defended the Eurocentrism of these books while suggesting that their view of the Enlightenment as an acclamation of universal values (comprehensible and extendable outside the European ethnic homeland) was itself accountable for the idea that its origins must not be restricted to Europe. Multicultural historians have merely carried to their logical conclusion the allegedly universal ideals of the Enlightenment. The standard interpretations of Tzvetan Todorov’s In Defence of the Enlightenment (2009), Stephen Bronner’s Reclaiming the Enlightenment (2004), and Robert Louden’s, The World We Want: How and Why the Ideals of the Enlightenment Still Eludes Us (2007), equally neglect the intense interest Enlightenment thinkers showed in the division of humanity into races. They similarly pretend that, insomuch as these thinkers spoke of “reason,” “humanity,” and “equality,” they were thinking outside or above the European experience and intellectual ancestry.

What about Justin Smith, or, since he has not published in this field, the left liberal authors on this topic? There is not that much; the two best known sources are two anthologies of writings on race, namely, Race and the Enlightenment: A Reader (1997), edited by Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze; and The Idea of Race (2000), edited by Robert Bernasconi and Tommy Lott. Eze’s book gathers into a short book the most provocative writings on race by some Enlightenment thinkers (Hume, Linnaeus, Kant, Buffon, Blumenbach, Jefferson and Cuvier). This anthology, valuable as it is, is intended for effect, to show how offensively racist these thinkers were. Eze does not disprove the commonly accepted idea that Enlightenment thinkers were proponents of a universal ethos (although, as we will see below, Eze does offer elsewhere a rather acute analysis of Kant’s racism). Bernasconi’s The Idea of Race is mostly a collection of nineteenth and 20th century writings, with short excerpts from Francois Bernier, Voltaire, Kant, and Blumenbach. The books that Malik mentions (see above) which connect the Enlightenment to racism are also insufficient: George Mosse’s Toward the Final Solution: A History of European Racism (1985) is just another book about European anti-Semitism, which directs culpability to the Enlightenment for carrying classifications and measurements of racial groups. David Goldberg’s Racist Culture (1993) is a study of the normalization of racialized discourses in the modern West in the 20th century.

There are, as we will see later, other publications which address in varying ways this topic, but, on the whole, the Enlightenment is normally seen as the most critical epoch in “mankind’s march” towards universal brotherhood. The leftist discussion of racist statements relies on the universal principles of the Enlightenment. Its goal is to uncover and challenge any idea among 18th century thinkers standing in the way of a future universal civilization. Leftist critics enjoy “exposing” white European males as racists and thereby re-appropriate the Enlightenment as their own from a cultural Marxist perspective. But what if we were to approach the racism and universalism of the Enlightenment from a New Right perspective that acknowledges straightaway the particular origins of the Enlightenment in a continent founded by Indo-European [10] speakers?

This would involve denying the automatic assumption that the ideas of the philosophes were articulated by mankind and commonly true for every culture. How can the ideas of the Enlightenment be seen as universal, representing the essence of humanity, if they were expressed only by European men? The Enlightenment is a product of Europe alone, and this fact alone contradicts its universality. Enlightenment thinkers are themselves to blame for this dilemma expressing their ideas as if “for men of all times and places.” Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803), writing at the same time as Kant, did question the notion of a cosmopolitan world based on generic human values. He saw in the world the greatest possible variety of historical humans in different regions of the earth, in time and space. He formulated arguments against racial rankings not by questioning their scientific merits as much as their reduction of the diversity of humans to one matrix of measurement and judgment. It was illusory to postulate a universal philosophy for humanity in which the national character of peoples would disappear and each human on earth would “love each other and every one . . . being all equally polite, well-mannered and even-tempered . . . all philanthropic citizens of the world.”[1] Contrary to some interpretations, Herder was not rejecting the Enlightenment but subjecting it to critical evaluation from his own cosmopolitan education in the history and customs of the peoples of the earth. “Herder was among the men of the Enlightenment who were critical in their search for self-understanding; in short, he was part of the self-enlightening Enlightenment.”[2] He proposed a different universalism based on the actual variety and unique historical experiences and trajectories of each people (Volk). Every people had their own particular language, religion, songs, gestures, legends and customs. There was no common humanity but a division of peoples into language and ethnic groups. Each people were capable of achieving education and progress in its own way from its own cultural sources.

From this standpoint, the Enlightenment should be seen as an expression of a specific people, Europeans, made up of various nationalities but nevertheless in habitants of a common civilization who were actually conceiving the possibility of becoming good citizens of Europe at large. In the words of Edward Gibbon, Enlightenment philosophers were enlarging their views beyond their respective native countries “to consider Europe as a great republic, whose various inhabitants have attained almost the same level of politeness and cultivation” (in Gay, 13).

Beyond Herder, we also need to acknowledge that the Enlightenment inaugurated the study of race from a rational, empirical, and secular perspective consistent with its own principles. No one has been willing to admit this because this entire debate has been marred by the irrational, anti-Enlightenment dogma that race is a construct and that the postulation of a common humanity amounts to a view of human nature without racial distinctions. Contrary to Roy Porter, there was a party line, or, to be more precise, a consistently racial approach among Enlightenment thinkers. The same philosophes who announced that human nature was uniform everywhere, and united mankind as a subject capable of enlightenment, argued “in text after text . . . in the works of Hume, Diderot, Montesquieu, Kant, and many lesser lights” that men “are not uniform but are divided up into sexes, races, national characters . . . and many other categories” (Garret 2006). But because we have been approaching Enlightenment racism under the tutelage of our current belief that race is “a social myth” and that any division of mankind into races is based on malevolent “presumptions unsupported by available evidence [11],” we have failed to appreciate that this subject was part and parcel of what the philosophes meant by “enlightenment.” Why it is so difficult to accept the possibility that 18th century talk about “human nature” and the “unity of mankind” was less a political program for a universal civilization than a scientific program for the study of man in a way that was systematic in intent and universal in scope? It is quite legitimate, from a scientific point, to treat humans everywhere as uniformly constituted members of the same species while recognizing their racial and cultural variety across the world. Women were considered to be intrinsically different from men at the same time that they were considered to be human.

Not being an expert on the Enlightenment I found recently a book chapter titled “Human Nature” by Aaron Garrett in a two volume work, The Cambridge History of Eighteenth-Century Philosophy [12] (2006). There is a section in this chapter dealing with “race and natural character”; it is short, 20 pages in a 1400 page work, but it is nevertheless well researched with close to 80 footnotes of mostly primary sources. One learns from these few pages that “in text after text” Enlightenment thinkers proposed a hierarchical view of the races. Mind you, Garrett is stereotypically liberal and thus writes of “the 18th century’s dubious contributions to the discussion of race,” startled by “the virulent denigrations of blacks . . . found in the works of Franklin, Raynal, Voltaire, Forster, and many others.” He also playacts the racial ideas of these works as if they were inconsistent with the scientific method, and makes the very unscientific error of assuming that there was an “apparent contradiction” with the Enlightenment’s notion of a hierarchy of races and its “vigorous attacks on the slave trade in the name of humanity.”