jeudi, 09 mai 2024

Daria Douguina: Lumières et post-lumières : lumière ou ténèbres ?

Lumières et post-lumières : lumière ou ténèbres ?

Daria Douguina

Source: https://www.geopolitika.ru/el/article/diafotismos-kai-meta-diafotismos-fos-i-skotadi

Le dialogue entre la postmodernité et la philosophie classique est aussi exotique et étrange que la postmodernité elle-même. Au cœur de la philosophie moderniste se trouve une stratégie étrange et complexe: il est nécessaire de démanteler complètement la modernité, en ne négligeant aucune pierre, mais en même temps, il est nécessaire de s'éloigner davantage de la tradition à laquelle la modernité s'est opposée et de poursuivre la cause du progrès.

L'ambition de devenir encore plus progressiste que les penseurs de la Modernité est généralement ce qui retient le plus l'attention. C'est comme si les modernistes ne faisaient que déplacer la Modernité à la place de la Tradition et se substituaient à la véritable avant-garde. C'est l'approche des « exotéristes de gauche » (Mark Fischer, Nick Srnicek, etc.).

Pour eux, les classiques de la philosophie postmoderne, et en premier lieu Gilles Deleuze, ont quelque chose de « lumineux », de « libérateur » et de « révolutionnaire ».

Mais il y a aussi les « accélérationnistes de droite » (Nick Land, Reza Negarestani, etc.), qui comprennent toute l'ambivalence de la modernité et ne détournent pas leur regard de ses aspects les plus sombres - après tout, en écrasant la modernité, les modernistes jettent aussi le tabouret sous leurs propres pieds, quand ils sont accrochés à la potence, puisque le progressisme et la foi en un avenir meilleur n'ont plus de fondement.

Cela affecte également la lecture de Deleuze, dans laquelle les « Accélérationnistes de droite » commencent à discerner des côtés tout à fait sombres. C'est ainsi que naît la figure du « sombre Deleuze », dont le travail ouvertement destructeur de démantèlement des illusions du monde moderne (de la modernité) apparaît dans une perspective plutôt infernale. Bienvenue dans les « Lumières sombres ».

En tout état de cause, les modernistes de gauche comme de droite ne se tournent pas vers la Tradition, mais leur lecture de la Modernité elle-même est polaire. De même, l'attitude des modernes à l'égard des fondateurs de la philosophie de la modernité semble très différente.

J'essaierai d'examiner la relation entre deux figures emblématiques de la philosophie : Leibniz et Deleuze.

L'un a appartenu au début de la modernité, l'autre en a résumé les résultats et a marqué l'épanouissement de la postmodernité. Je ne porterai pas de jugement définitif sur la manière dont Deleuze doit être compris, qu'il s'agisse de l'ombre ou de la lumière. J'essaierai simplement de retracer ce que le système de Deleuze fait de la « monadologie ».

Extrait du livre : Optimisme eschatologique.

09:05 Publié dans Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : daria douguina, gilles deleuze, modernioté, philosophie des lumières, lumières |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 27 octobre 2017

R. Steuckers: Naar een nieuwe gouden eeuw?

Naar een nieuwe gouden eeuw?

Interventie van Robert Steuckers

Colloquium van de Studiegenootschap "Erkenbrand"

Rotterdam, 14 oktober 2017

Als we wensen terug te keren naar een gouden tijdperk, d. w. z. naar een gouden tijdperk dat in overeenstemming met onze echten “roots” is en dat zeker geen product van een soort sociaal engineering is, een gouden tijdperk dus dat wel een terugkeer naar bronnen betekent zonder tegelijkertijd een afkeer van wetenschappelijke of technische vooruitgang te zijn, en niet enkel op militair vlak, dan is deze terugkeer naar een gouden tijdperk een vorm van archeofuturisme waarbij de toekomst van onze volkeren door eeuwige en vaste waarden wordt bepaald. Een terugkeer naar een gouden tijdperk betekent weer leven te geven aan waarden die zeker in de Astijd der geschiedenis aanwezig waren of die nog eerder in een verder verleden de geest van onze voorouders hebben bepaald.

Men kan die waarden “traditie” noemen of niet, ze zijn wel de bakermat van onze beschaving die veel dieper wortelen dan de pseudo-waarden van een flauwe of pervers geworden Verlichting. En als wij de Verlichting beschouwen als een geestelijk voertuig van perversiteit, bedoelen we het huidige progressivisme dat werkt als een instrumentarium dat één enkel doel heeft: de oeroude waarden en de waarden van de Astijd der geschiedenis uit te schakelen. De uitschakeling van deze waarden belet ons een toekomst te hebben, want wie geen waarden meer in zich draagt loopt oriënteringsloos in de wereld rond en verliest zijn politieke “Gestaltungskraft”.

Om Arthur Moeller van den Bruck te parafraseren die dit in de jaren 20 van de vorige eeuw schreef; dat het liberalisme na een paar decennia de volkeren doodt die volgens zijn regels hun leven hebben bepaald. Vandaag, met een hernieuwde woordenschat, ben ik van mening dat ieder ultra-gesimplificeerde ideologie, die beweert de Verlichting als inspiratiebron te hebben, de “Gestaltungskraft” van de volkeren in de kiem smoort. Frankrijk, Engeland, gedeeltelijk de Verenigde Staten en voornamelijk het verwesterse Duitsland zijn vandaag de voorbeelden van zo’n dramatische “involutie”.

De Verenigde Staten en Duitsland mogen wel een uitstekende technische ontwikkeling hebben vertoond of nog altijd vertonen; of, beter gezegd, bezitten deze beide mogendheden vanaf het einde van de 19de eeuw een hoog technisch niveau, er zijn echter talrijke aanwijzingen die wijzen op een volledige verloedering van hun samenlevingen. In Duitsland gebeurt dat door de toepassing van een bewuste strategie, de zogenoemde strategie van de “Vergangenheitsbewältigung”, waardoor het verleden systematisch wordt beschreven en beschouwd als de bron van het absolute kwaad en dat geldt niet uitsluitend voor het nationaal-socialistisch verleden. Dit proces speelt in op de eigen nationale zelfwaardering en induceert een totale aanvaarding van alle mogelijke politieke of sociale praktijken die de samenleving definitief kelderen, waarbij de vluchtelingenpolitiek van mevrouw Merkel het summum betekent, een summum dat de buurlanden uit de Visegrad-Groep niet bereid zijn klakkeloos te accepteren.

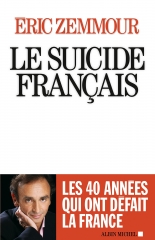

In Frankrijk ziet men een aftakeling van de vroeger heilige sterke staat, die De Gaulle nog wou handhaven. Eric Zemmour heeft onlangs de geschiedenis van de “Franse zelfmoord” (le “Suicide français”) op een voortreffelijke manier geschetst. Daarbij mag nog gezegd worden dat een boek uit de vroege jaren 80 een perfide rol heeft gespeeld in het ontstaan van een eigen Franse “Vergangenheitsbewältigung”: dat boek heeft als titel “L’idéologie française” en werd neergepend door de beroemde Bernard-Henri Lévy. In dat boek worden alle niet-liberale en/of alle niet sociaal-democratische politieke strekkingen als fascistisch bestempeld, inclusief sommige belangrijke aspecten van het archaïstisch Franse communisme, van het gaullisme in het algemeen, en zelfs van het christelijke personalisme van een aarzelende ideoloog zoals Emmanuel Mounier. Juist in het boek van Lévy vinden we alle instrumenten van wat een Nederlander, namelijk de Frankrijk-specialist Luk de Middelaar, heel correct als “politicide” heeft omgeschreven.

In naoorlogs Duitsland werd de Verlichting als de filosofische strekking beschouwd die de Duitsers en de andere Europeanen immuun moest maken tegen het politieke kwaad. Jürgen Habermas zou dus heel snel de theoreticus par excellence worden van deze nieuwe West-Duitse Verlichting die het kwade verleden moest uitwissen.

Maar de gevulgariseerde Habermasiaanse Verlichting, toegepast door ijverige journalisten en feuilletonisten, is maar een “deelverlichting” voor eenieder die de culturele geschiedenis van de 18de eeuw nauwkeurig heeft bestudeerd. De wereld is inderdaad niet zo simpel als de heer Habermas en zijn schare volgelingen het wensen. De “political correctness” werkt dus op basis van een afgeroffelde en geknoeide interpretatie van wat eigenlijk in haar verscheidene aspecten de Verlichting was.

De Verlichting volgens de “Frankfurter Schule” en volgens haar “Musterschüler” Habermas, is misschien wel een min of meer legitieme erflating van de 18de eeuwse Verlichting, maar er zijn ook andere en vruchtbaardere onderdelen van de historische Verlichting. De huidige politiek correcte Verlichting is enkel een slechte combinatie van “blueprints”, om de uitdrukking van de Engelsman Edmund Burke over te nemen, toen hij de bloedige uitspattingen van de Franse revolutie beschreef. Burke is inderdaad geen obscurantist of een aanhanger van een oubollige scholastiek. Hij bekritiseert de Franse revolutie, omdat die een valse interpretatie van de rechten van de mens suggereert. Er zijn dus andere mogelijkheden om de rechten van de mens te interpreteren, eerst en vooral omdat het Ancien Régime geen juridisch woestijn was en omdat de concrete gemeenschappen wel goed geprofileerde rechten hadden.

Later ontstond er in de Keltisch-sprekende randgebieden van het Verenigd Koninkrijk en in het bijzonder in de Ierse Republiek een andere manier om aan de burgers rechten te garanderen zonder de verlichte geest van emancipatie te negeren en ook zonder de Keltische roots van Ierland te loochenen. Na de Tweede Wereldoorlog, hebben Ierse juristen en ministers, volgens het VN-boekje over de mensenrechten en volgens hun eigen Pankeltische ideologie, de Franse Republiek laten veroordelen nadat ze het onterecht veroordelen of vermoorden van Bretoense militanten had verdedigd. En, opgelet, deze Ierse minister McBride was de voorzitter van Amnesty International en werd later Nobelprijs winnaar in 1974. De Republiek, die Lévy beschouwt als een stelsel dat het summum van politieke correctheid zou belichamen, werd destijds veroordeeld wegens schending van de mensenrechten!

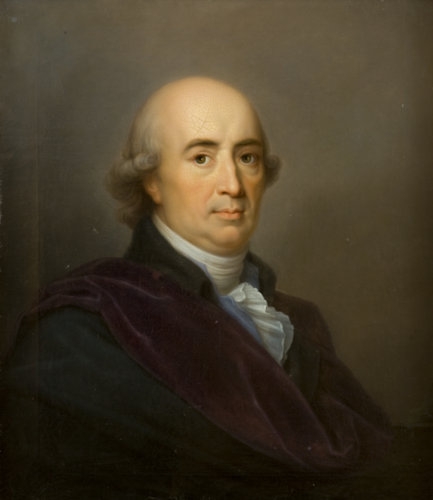

Verder, omdat wij het hier over een gouden tijdperk hebben, bestaat er ook zoiets dat jammer genoeg in vergetelheid is geraakt in continentaal Europa: de Verlichting volgens Johann Gottfried Herder, die gelukkig een soort bescheiden comeback kent in de Altright beweging in de Angelsaksische wereld.

Volgens Herder, als belichaming van de Duitse 18de eeuwse Verlichting, moeten wij twee principes respecteren en als leidende beginsels steeds gebruiken: “Sapere aude” (Durf te weten) en “Gnôthi seauton” (Ken jezelf). Er bestaat geen echte Verlichting, volgens deze Evangelische dominee uit Riga in het huidige Letland, zonder deze beide principes te vereren. Zou een filosofisch-politieke strekking beweren dat ze “verlicht” is zonder dat ze aanneemt dat men over de “Schablonen” of de gemeenplaatsen durft denken, die momenteel heersen en de samenleving tot een gevaarlijke stilstand leiden, dan is zulk een Verlichting geen reële en efficiënte Verlichting, maar een instrument om een dwingelandij op te leggen. Een volk moet dus zichzelf kennen, terug naar de oeroudste bronnen keren om werkelijk weer vrij te worden. Er bestaat geen vrijheid als er geen geheugen meer bestaat. Werken aan het opwaken van het slapende geheugen betekent aldus de allereerste stap naar de herovering van de vrijheid, en uiteindelijk van de capaciteit, vrij en nuttig te handelen op internationaal niveau. Herder vraagt ons dus om terug naar de bronnen van onze eigen cultuur te keren zonder de perverse wil om deze “roots” uit te wissen.

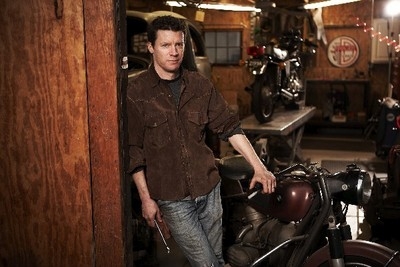

Een gouden tijdperk kan alleen in de Europese samenleving terugkeren als de politieke instellingen van de valse en oppervlakkige Verlichting en van de politieke correctheid door een nieuwe en krachtige Verlichting volgens de denkwegen van Herder wordt vervangen. Heidegger zou juist hetzelfde zeggen, maar wel in andere woorden: voor de filosoof van het Zwarte Woud en het “Schwabenland”, was de Europese beschaving slachtoffer van “het onkruid van de Westerse metafysiek”, welk onkruid opgeruimd moest worden, waarmee “een nieuwe dageraad kon ontstaan”. De woordenschat, die Heidegger gebruikte, is ongelofelijk moeilijk voor de gewone leek. De Amerikaanse docent filosofie Matthew B. Crawford schetst op een korte en bondige manier de bedoeling van Heidegger: voor Crawford van de Virginia University is de “Westerse metafysiek” van de Duitse filosoof eenvoudigweg de pseudo-verlichte janboel van Locke & Co, dus de Engelse of Franse Verlichting, die geen contact met de werkelijkheid meer heeft of beter gezegd geen contact met het concrete wil hebben. Er bestaan dus twee “Verlichtingen”, de organische van Herder en de abstracte van de anderen, die de werkelijkheid en het werkelijke verleden van de volkeren weigeren.

In dit perspectief stelt Crawford vast, dat iedere samenleving, die onder de invloed van de officiële interpretatie van de Verlichting blijft stagneren, gedoemd is af te takelen en uiteindelijk te sterven. Daarom nam hij ooit afscheid van zijn katheder en ging een garage voor Harley-Davidson motorfietsen openen, om heel reëel de geur van olie, benzine en leder te genieten, om naar de muziek van het gereedschap op metaal te kunnen luisteren. Uiteraard hebben wij hier met een voor een docent filosofie zeldzame terugkeer naar het concrete van doen. Op politiek, maar ook op economisch en sociaal vlak betekent het, dat wij de wereldvreemdheid van het huidige systeem in al zijn facetten hardnekkig moeten verwerpen. Daar ligt inderdaad onze hoofdopdracht. Eigenlijk heet dat vechten om het concrete te redden, wat ook uiteindelijk de bedoeling van Heidegger in alle aspecten van zijn reusachtig filosofisch werk was.

Dat betekent niet noodzakelijk een rage om een nieuw totalitair stelsel te promoten, wat misschien voor een tijdje de wens van Heidegger was, maar zeker en vast de wil om de vrijheid van de burgers en volkeren te redden tegen een systeem dat een werkelijke dwangbuis aan het worden is. Naast Heidegger, die in Duitsland was gebleven, is er ook in het wereldje der filosofen zijn vroegere studente en maîtresse Hannah Arendt, die meer bepaalt in haar nieuwe Amerikaanse vaderland voor de vrijheid heeft gepleit tegen de banaliteit van onze Westerse liberale samenlevingen en van het Sovjetcommunisme. En inderdaad, na de val van het communisme in Rusland en Oost-Europa, heeft de Verlichting van Habermas en zijn volgelingen tot een absolute beperking van de burgerlijke vrijheden in West-Europa geleid, heel eenvoudig omdat in de ogen van de machthebbers in bijna alle Europese staten niets meer MAG bestaan, dat vroeger een ruggengraat aan ieder welke samenleving gaf. In naam van een abstracte en wereldvreemde vrijheidsnotie worden de wortels van iedere samenleving afgekapt, waarmee men de verbintenis tussen identiteit en vrijheid negeert.

Er bestond in de 18de eeuw een nog andere Verlichting, een derde Verlichting, namelijk de Verlichting van de “verlichte despoten”, die hun landen hebben gemoderniseerd op alle praktische vlakken, zonder tegelijkertijd de traditionele waarden van hun volkeren te vernietigen. Voor de “verlichte despoten”, zoals Frederik van Pruisen, Maria-Theresa of Jozef II van Oostenrijk, Catharina II van Rusland of Karel III van Spanje, betekende Verlichting de technische modernisering van hun land, het bouwen van straten en kanalen, een moderne stedenbouw, een efficiënt corps van bekwame ingenieurs in hun legers, etc. De allereerste functie van een staat is inderdaad zulke werkzaamheden mogelijk te maken en het leger steeds paraat te houden voor iedere dreiging, volgens het Latijnse motto “Si vis pacem, para bellum”.

Dit brengt ons weer naar onze huidige dagen: iedereen in deze zaal is zich wel bewust dat zelfs ieder onschuldige en ongevaarlijke poging onze identiteit te verdedigen door de wakende honden in het medialandschap als fout kan worden beschouwd, met het welbekende risico naar een bruin hoekje verbannen te worden. Maar onze tijdgenoten zijn zich minder van een ander dodelijk gevaar bewust: de aftakeling van industriebranches overal in Europa, dankzij het verfoeilijke neoliberale principe van delocalisatie, waarbij men moet weten dat het neoliberalisme de gekste gedaanteverwisseling van de heersende Verlichting is. Delocaliseren betekent juist de erfenis van de “verlichte despoten” te verloochenen, ofwel de ideeën van een geniale 19de-eeuwse economist en ingenieur zoals Friedrich List. (wiens principes nu uitsluitend door China worden uitgebaat, wat het succes van Beijing klaar en duidelijk kan uitleggen) De Gaulle, die Clausewitz als jonge gevangene officier in Ingolstadt gedurende de 1ste wereldoorlog volledig had doorgelezen, was een aanhanger van deze twee concrete Pruisische denkers. Hij trachtte in de jaren 60 van de vorige eeuw hun principes in Frankrijk te realiseren. Het is dit “verlicht” werk dat stap voor stap werd vernield, volgens Zemmour, zodra Pompidou aan de macht kwam: het heel recente verkoop van het hoogtechnologisch bedrijf Alstom door Macron aan Amerikaanse, Duitse, Italiaanse consortiums betekent bijna het einde van het proces: Frankrijk ligt nu bloot en kan niet meer beweren dat het nog een grootmacht is. De Gaulle draait zich om in zijn graf, in het afgelegen dorpje Colombey-les-deux-églises.

Dit brengt ons weer naar onze huidige dagen: iedereen in deze zaal is zich wel bewust dat zelfs ieder onschuldige en ongevaarlijke poging onze identiteit te verdedigen door de wakende honden in het medialandschap als fout kan worden beschouwd, met het welbekende risico naar een bruin hoekje verbannen te worden. Maar onze tijdgenoten zijn zich minder van een ander dodelijk gevaar bewust: de aftakeling van industriebranches overal in Europa, dankzij het verfoeilijke neoliberale principe van delocalisatie, waarbij men moet weten dat het neoliberalisme de gekste gedaanteverwisseling van de heersende Verlichting is. Delocaliseren betekent juist de erfenis van de “verlichte despoten” te verloochenen, ofwel de ideeën van een geniale 19de-eeuwse economist en ingenieur zoals Friedrich List. (wiens principes nu uitsluitend door China worden uitgebaat, wat het succes van Beijing klaar en duidelijk kan uitleggen) De Gaulle, die Clausewitz als jonge gevangene officier in Ingolstadt gedurende de 1ste wereldoorlog volledig had doorgelezen, was een aanhanger van deze twee concrete Pruisische denkers. Hij trachtte in de jaren 60 van de vorige eeuw hun principes in Frankrijk te realiseren. Het is dit “verlicht” werk dat stap voor stap werd vernield, volgens Zemmour, zodra Pompidou aan de macht kwam: het heel recente verkoop van het hoogtechnologisch bedrijf Alstom door Macron aan Amerikaanse, Duitse, Italiaanse consortiums betekent bijna het einde van het proces: Frankrijk ligt nu bloot en kan niet meer beweren dat het nog een grootmacht is. De Gaulle draait zich om in zijn graf, in het afgelegen dorpje Colombey-les-deux-églises.

Dus de valse, heersende Verlichting eist bloeddorstig twee slachtoffers: de identiteit als geestelijke erfenis, die totaal uitgewist moet worden en de economisch-industriële structuur van ieder land, zij het van een grootmacht of een kleinere mogendheid, die vernield dient te worden. Deze ideologie is dus werkelijk gevaarlijk op alle vlakken en dient zo gauw mogelijk en definitief opzijgelegd te worden. De zogenaamde “liberal democracies” riskeren vroeg of laat een langzame dood als dat van een kanker- of Alzheimerpatiënt, terwijl de “illiberal democracies” à la Poetin of à la Orban, of op Poolse wijze, of het confuciaans Chinees systeem, stilaan en stilzwijgend de overhand krijgen en harmonieus bloeien op sociaal en economisch vlak. De totale amnesie en de totale ontwapening, die de Lockistische Verlichting van ons eist, verzekert ons van maar één lot: het uitsterven in schande, armoede en verloedering.

Het geneesmiddel is heel duidelijk en laat zich in één toverwoord samenvatten, “archeofuturisme”, door Guillaume Faye ooit uitgedokterd: d. w. z. de troeven te bundelen die bestaan uit de bronnen die Herder eenmaal zong, de organisatie van de staat volgens Clausewitz, de organisatie van de economie en het bouwen van infrastructuren zoals List het preconiseerde.

Crawford, de professor-garagehouder, stelt een nog veel langere lijst van gevaren vast, die voortvloeien uit wat hij het Engelse verlichte “Lockisme” noemt. Deze versie van de Verlichting heeft een wereldvreemde houding tegenover de geschiedenis en de algemene werkelijkheid laten ontstaan, wat Heidegger later, volgens Crawford, de “Westerse metafysiek” zal noemen. In de ogen van de eremiet van Todtnauberg betekent deze metafysiek een afkeer van de werkelijke en organische feiten, van het leven tout court, ten gunste van droge en onvruchtbare abstracties die de wereld en de organisch gegroeide samenlevingen en staten naar een zekere implosie en een zekere dood brengen.

In de zogenaamde “Nieuw Rechtse” kringen nam de kritiek van de Verlichting in een eerste stap de gedaante van een kritiek op de nieuwe ideologie van de “mensenrechten”, die onder President Carter vanaf 1976 ontstond om de betrekkingen met de Sovjetunie te vermoeilijken en de Olympische Spelen in Moskou te kelderen. De nieuwe diplomatie van de mensenrechten, die toen ontstond, werd terecht als breuk met de klassieke diplomatie en de realpolitik van Kissinger beschouwd. Om deze nieuwe ideologie in de internationale betrekkingen te promoten werd er een regelrecht, metapolitiek offensief gevoerd, met alle middelen van de ervaren Amerikaanse soft power. Er werden instrumenten in de heksenkeukens van de geheime diensten ontworpen, die aan ieder nationale context aangepast werden: in Frankrijk en voor de Franstalige omgeving was het instrument de zogenaamde “nouvelle philosophie” met figuren zoals Bernard-Henri Lévy en André Glucksmann. Vanaf het einde van de jaren 70 zijn de grof geknutselde standpunten van voornamelijk Lévy altijd overeengekomen met de geopolitieke doelen van de Verenigde Staten, tot en met de gruwelijke dood van Kolonel Khadafi in Libië en zijn huidige steun aan de Koerden in Irak en Syrië.

Tegenover deze enorme middelen van de soft power, had Nieuw Rechts weinig kans om gehoor te krijgen. En de argumenten van zijn sprekers, alhoewel in het algemeen juist, waren tamelijk zwak op filosofisch vlak, even zwak kan ik nu zeggen als degenen van Lévy zelf. De toestand heeft zich sinds enkele jaren gewijzigd: de geknutselde ideologie van de mensenrechten en van de pseudo-diplomatie op internationaal niveau, die ze begeleiden en die tot een lange reeks rampzalige resultaten hebben geleid, ondergaan nu scherpe kritiek vanuit alle mogelijke ideologische hoeken. Twee Brusselse professoren, trouwens van de linkse Universiteit van Brussel, Justine Lacroix en Jean-Yves Pranchère, hebben het oude dossier van de mensenrechten klaar en duidelijk samengevat. De ideologie van de mensenrechten wordt steeds gebruikt om geërfde instellingen of zelfs rechten te kelderen, zoals Burke het onmiddellijk na de uitroeping ervan bij het begin van de Franse Revolutie kon observeren. Burke was een figuur van het Britse conservatisme. Later werd deze ideologie ook door linkse en liberale krachten bekritiseerd. Jeremy Bentham en Auguste Comte beschouwden ze als een hindernis voor het “algemeen belang”; Marx vond dat ze de kern van de burgerlijke ideologie waren en dus ook een hindernis, maar ditmaal tegen de emancipatie van de brede massa’s. Wij kunnen vandaag de dag deze ideologie evenwel als een instrument van een buiten-Europese mogendheid bekritiseren, maar ook als een instrument van de algemene subversiviteit die zowel geërfde instellingen als traditionele volkse rechten uitwissen wil. Deze ideologie heeft ook geen maatschappelijk nut meer, daar men ermee geen enkel probleem kan oplossen en zich er alleen maar nieuwe onoplosbare toestanden creëren. Dus zijn alle mogelijke kritieken op de mensenrechten nuttig om een breed front te laten ontstaan tegen de politieke correctheid, waarbij de eerste stap altijd de wil moet zijn, de rechten, de samenlevingen en de economie terug in hun organische en historische omgeving te brengen.

Tegenover deze enorme middelen van de soft power, had Nieuw Rechts weinig kans om gehoor te krijgen. En de argumenten van zijn sprekers, alhoewel in het algemeen juist, waren tamelijk zwak op filosofisch vlak, even zwak kan ik nu zeggen als degenen van Lévy zelf. De toestand heeft zich sinds enkele jaren gewijzigd: de geknutselde ideologie van de mensenrechten en van de pseudo-diplomatie op internationaal niveau, die ze begeleiden en die tot een lange reeks rampzalige resultaten hebben geleid, ondergaan nu scherpe kritiek vanuit alle mogelijke ideologische hoeken. Twee Brusselse professoren, trouwens van de linkse Universiteit van Brussel, Justine Lacroix en Jean-Yves Pranchère, hebben het oude dossier van de mensenrechten klaar en duidelijk samengevat. De ideologie van de mensenrechten wordt steeds gebruikt om geërfde instellingen of zelfs rechten te kelderen, zoals Burke het onmiddellijk na de uitroeping ervan bij het begin van de Franse Revolutie kon observeren. Burke was een figuur van het Britse conservatisme. Later werd deze ideologie ook door linkse en liberale krachten bekritiseerd. Jeremy Bentham en Auguste Comte beschouwden ze als een hindernis voor het “algemeen belang”; Marx vond dat ze de kern van de burgerlijke ideologie waren en dus ook een hindernis, maar ditmaal tegen de emancipatie van de brede massa’s. Wij kunnen vandaag de dag deze ideologie evenwel als een instrument van een buiten-Europese mogendheid bekritiseren, maar ook als een instrument van de algemene subversiviteit die zowel geërfde instellingen als traditionele volkse rechten uitwissen wil. Deze ideologie heeft ook geen maatschappelijk nut meer, daar men ermee geen enkel probleem kan oplossen en zich er alleen maar nieuwe onoplosbare toestanden creëren. Dus zijn alle mogelijke kritieken op de mensenrechten nuttig om een breed front te laten ontstaan tegen de politieke correctheid, waarbij de eerste stap altijd de wil moet zijn, de rechten, de samenlevingen en de economie terug in hun organische en historische omgeving te brengen.

Voor Crawford leiden de subversieve Verlichting à la Locke en haar talrijke avataren naar de hedendaagse ziekte, die in het bijzonder kinderen en jongeren treft: het verlies van de “capaciteit, steeds aandachtig te zijn” of wat Duitse pedagogen zoals Christoph Türcke de “Aufmerksamkeitsdefizitkultur” noemen. Onze jonge tijdgenoten zijn dus de laatste slachtoffers van een lang proces, die twee, drie eeuwen geleden, zijn aanvang kende. Maar dit is ook het einde van het subversieve en “involutieve” proces, dat ons naar een “Kali Yuga” heeft geleid. De mythologie vertelt ons dat na de Kali Yuga een nieuwe gouden tijdperk zal beginnen.

Voor Crawford leiden de subversieve Verlichting à la Locke en haar talrijke avataren naar de hedendaagse ziekte, die in het bijzonder kinderen en jongeren treft: het verlies van de “capaciteit, steeds aandachtig te zijn” of wat Duitse pedagogen zoals Christoph Türcke de “Aufmerksamkeitsdefizitkultur” noemen. Onze jonge tijdgenoten zijn dus de laatste slachtoffers van een lang proces, die twee, drie eeuwen geleden, zijn aanvang kende. Maar dit is ook het einde van het subversieve en “involutieve” proces, dat ons naar een “Kali Yuga” heeft geleid. De mythologie vertelt ons dat na de Kali Yuga een nieuwe gouden tijdperk zal beginnen.

In de donkere tijden voor dit nieuwe gouden tijdperk, dus in de tijden die wij nu beleven, is de eerste taak van degenen die zich van deze verloedering bewust zijn, hyperaandachtig te zijn en te blijven. Als de Verlichting à la Locke of de “Westerse metaphysiek” ons de concrete wereld als een verdoemenis beschreef, die niet waardig was de aandacht van de filosoof of de intellectueel aan te trekken, als deze Verlichting de realiteit als een miserabele hoop onwaardige spullen zag, als de ideologie van de mensenrechten de geschiedenis en de realisaties van onze voorouders ook als onwaardig of zelfs als crimineel beschouwde, wil de Verlichting à la Herder juist het tegendeel. De volkse/organische Verlichting van Herder wil juist aandacht besteden aan “roots” en bronnen, aan geschiedenis, literatuur en volkse tradities. De echte politieke en strategische doelen, die de “verlichte despoten” en de aanhangers van Friedrich List in hun respectievelijke staten en samenlevingen ontplooien, eisen van de politieke verantwoordelijken een constante aandacht voor de fysieke werkelijkheden van hun landen, om ze te beheren of om ze zo te “gestalten” dat ze nuttig worden voor de volkeren die erin leven. Terug te keren naar een gouden tijdperk betekent dus afscheid te nemen van alle ideologieën, die de aandachtcapaciteit van de successieve generaties heeft vernietigd, tot de catastrofe die wij nu beleven.

Maar als de wil de aandacht op het concrete terug te vestigen een langdurig proces is, zal er toch noodzakelijk een tijd voor de kairos moeten komen. Kairos is de Griekse god voor de sterke tijd, terwijl Chronos de god is van de meetbare tijd, van de saaie chronologie, van wat Heidegger de “Alltäglichkeit” noemde. De Nederlandse Joke Hermsen heeft drie jaar geleden een boek over de kairos geschreven: de sterke tijd, die hij mythisch belichaamt, is de tijd van de beslissing, van de conservatief-revolutionaire “Entscheidung” (bij Heidegger, Schmitt en Jünger), waar geschiedenis wordt gemaakt. Kairos is de god van “het goede moment”, wanneer kansrijke volkskapiteinen het lot, het “Schicksal”, letterlijk vastpakken. Kairos is een jonge god met een bosje haar op zijn voorhoofd. Dat bosje moet de gelukkige, die het lot zal bedwingen, vastpakken. Een daad die moeilijk is, ook niet door eenvoudige berekening te voorzien is, maar als het gebeurt worden nieuwe tijden geboren en kan een nieuw gouden tijdperk gestart worden. Omdat nieuwe “Anfänge” leiden de taak is van de authentieke mens, volgens Heidegger en Arendt.

Misschien is er hier iemand die vroeg of later het bosje haar van Kairos zal vastpakken. Daarom heb ik dat hier Diets willen maken.

Ik dank jullie voor jullie aandacht.

05:14 Publié dans Nouvelle Droite, Synergies européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : robert steuckers, erkenbrand, nederland, âge d'or, lumières, philosophie des lumières, nieuw rechts, neue rechte, nouvelle droite, synergies européennes, habermas, herder |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 07 juin 2016

Montesquieu van twaalf kanten belicht

Boekrecensie

Door Paul Muys

Ex: http://www.doorbraak.be

Montesquieu van twaalf kanten belicht

Andreas Kinneging, Paul De Hert, Maarten Colette (red.)

Een vaak geciteerde denker waar toch veel misverstanden over bestaan

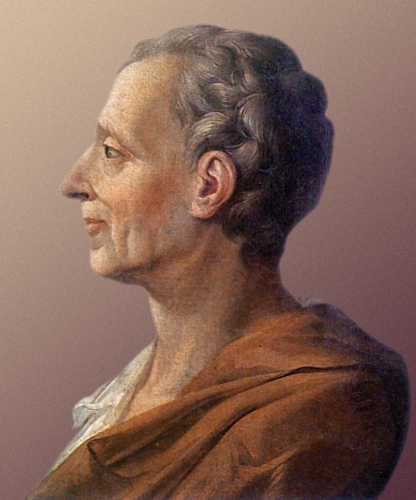

De wakkerste geesten onder u kennen baron de Montesquieu wel een beetje: de scheiding der machten, indertijd op school het obligate fragment uit de Lettres Persanes (Comment peut-on être Persan?) maar daar houdt het meestal bij op. Nu is er dit stevig gedocumenteerde werk waarin deze filosoof, voorloper van de Verlichting en grondlegger van de sociologie, vanuit diverse invalshoeken wordt bekeken.

Het onderwerp scheiding der machten is actueler dan ooit, nu dat kostbare beginsel weer moet worden verdedigd tegen de her en der dreigende sharia. In zijn hoofdwerk, De l’Esprit des Lois (Over de geest van de wetten) staat het bewuste principe centraal, net zoals dat van de checks and balances (zoiets als controles en waarborgen). Veelal getypeerd als een liberaal geeft Montesquieu in De l’Esprit aan dat hij na rijp beraad kiest voor een gematigde regering, gematigd door middel van de scheiding van de wetgevende, uitvoerende en rechterlijke macht. Liefst dan nog een regering waarin de adel een belangrijke rol vervult. Die machtenscheiding en de checks and balances liggen aan de basis van de Amerikaanse constitutie en die van een pak andere democratische landen, zonder die adel dan.

Het onderwerp scheiding der machten is actueler dan ooit, nu dat kostbare beginsel weer moet worden verdedigd tegen de her en der dreigende sharia. In zijn hoofdwerk, De l’Esprit des Lois (Over de geest van de wetten) staat het bewuste principe centraal, net zoals dat van de checks and balances (zoiets als controles en waarborgen). Veelal getypeerd als een liberaal geeft Montesquieu in De l’Esprit aan dat hij na rijp beraad kiest voor een gematigde regering, gematigd door middel van de scheiding van de wetgevende, uitvoerende en rechterlijke macht. Liefst dan nog een regering waarin de adel een belangrijke rol vervult. Die machtenscheiding en de checks and balances liggen aan de basis van de Amerikaanse constitutie en die van een pak andere democratische landen, zonder die adel dan.

Ook al is Montesquieu zelf edelman, dat hij zo’n belangrijke rol toekent aan deze stand kan verbazen. Nog verbazender is het voor de leek dat hij een bewonderaar is van de staatsvorm zoals het middeleeuwse Frankrijk die kende. Dat heeft alles te maken met de evolutie die de monarchie onder de Franse koningen doormaakt: van een gematigd koningschap, getemperd door de tussenmacht van de adel, evolueert zij naar absolutisme en zelfs despotisme. Het is een impliciete kritiek op Lodewijk XIV (L’état, c’est moi).

Macht en tegenmacht. Machtsdeling voorkomt machtsmisbruik. Montesquieu is geen Verlichtingsdenker, hij is niet per se tegen de monarchie, noch tegen de republiek overigens, al vreest hij dat die laatste minder doelmatig zal zijn dan in de Romeinse oudheid. Evenmin heeft hij bezwaar tegen de standen, op voorwaarde dat ook zij gecontroleerd worden door een tegenmacht. Precies omdat het Engeland van na de Glorious Revolution dit in de praktijk brengt, geeft Montesquieu het als voorbeeld. Het tweekamerstelsel (Hoger en Lagerhuis), waarbij elke kamer een sociaal verschillende samenstelling heeft, verhindert dat de adel zich kan bevoordelen. ‘Essentieel is’, zo betoogt co-auteur Lukas van den Berge, ‘dat de dragers van de drie machten geen van alle een primaat opeisen. In plaats daarvan dienen zij zich elk afzonderlijk te voegen naar een onderling evenwicht waaraan zij zich niet kunnen onttrekken zonder de politieke vrijheid om zeep te helpen.’

Vrijheid is voor Montesquieu niet zozeer de mogelijkheid tot politieke participatie of zelfbestuur – wat wij in de 21ste eeuw voetstoots aannemen – ze zit veeleer in de bescherming van de privésfeer. Annelien de Dijn betoogt: ‘Vrijheid is niet de macht van het volk, maar de innerlijke vrede die ontstaat uit het besef dat men veiligheid geniet.’ Dit kan onder vele verschillende regeringsvormen, op voorwaarde dat machtsmisbruik geen kans krijgt. Overheden hebben zich niet te bemoeien met zaken die mensen als persoon treffen, en niet als burger. Wanneer zij de dominante gewoonten en overtuigingen krenken, voelen mensen zich aangetast in hun vrijheid en ervaren dit als tirannie, zo schrijft Montesquieu in zijn commentaar op de mislukte poging van tsaar Peter de Grote om mannen bij wet te verbieden hun baard te laten groeien. Hij beveelt de tsaar andere methoden aan om zijn doel te bereiken. Paul De Hert: ‘Montesquieu pleit niet voor het recht om een baard te dragen. Zijn sociologische methode leert ons niet wat vrijheid zou moeten zijn, wel hoe vrijheid in een gegeven context ervaren wordt, of juist niet.’ Wat zou de observateur Montesquieu trouwens van het dragen van hoofddoeken in scholen en openbare diensten gedacht hebben?

Montesquieu zet zijn lezers vaak op het verkeerde been. Allicht verwijst de kwalificatie ‘enigmatisch’ in de titel hiernaar. Zo lezen we in de bijdrage van Jean-Marc Piret dat Montesquieu best kan leven met cliëntelisme, het uitdelen van postjes, waarbij de uitvoerende macht steun zoekt tegen de wetgevende kamers in. Wie geen voordelen uit die hoek hoeft te verwachten, zal dan weer zijn hoop op één van beide kamers stellen. Risico is daarbij dat teleurstelling mensen kan doen overlopen naar de tegenpartij. Schaamteloos opportunisme ? Volgens Montesquieu, die zich geen illusies maakt over hoe het er in de politiek toegaat, is dit juist een teken van de ‘pluralistische vitaliteit van de maatschappij’.

Montesquieu zet zijn lezers vaak op het verkeerde been. Allicht verwijst de kwalificatie ‘enigmatisch’ in de titel hiernaar. Zo lezen we in de bijdrage van Jean-Marc Piret dat Montesquieu best kan leven met cliëntelisme, het uitdelen van postjes, waarbij de uitvoerende macht steun zoekt tegen de wetgevende kamers in. Wie geen voordelen uit die hoek hoeft te verwachten, zal dan weer zijn hoop op één van beide kamers stellen. Risico is daarbij dat teleurstelling mensen kan doen overlopen naar de tegenpartij. Schaamteloos opportunisme ? Volgens Montesquieu, die zich geen illusies maakt over hoe het er in de politiek toegaat, is dit juist een teken van de ‘pluralistische vitaliteit van de maatschappij’.

Op zijn reizen stelt Montesquieu de achteruitgang vast van de Zeven Provinciën en van de republieken Venetië en Genua. Valt in Italië vooral corruptie op, in het achttiende-eeuwse Holland ziet hij alleen verval en kille zakelijkheid, sinds het land zich moest verweren tegen de invasie van Lodewijk XIV in 1672. De ooit zo bloeiende, creatieve koopmansstaat ziet zich verplicht een ruïneuze oorlog te voeren, die van de Hollanders een kil, berekenend, gesloten volk maakt, niet langer in staat tot grootse, creatieve daden. Het geweld is bovendien de grootste vijand van de eros, de humaniserende liefde zoals die groeide en bloeide ‘in het mediterrane land van wijn en olijven’, in Knidos in de Griekse oudheid (Le Temple de Gnide is een erotisch gedicht van Montesquieu naamloos uitgegeven in Amsterdam). Van de eros gesproken: Montesquieu is volgens een van de auteurs van dit boek, Ringo Ossewaarde, een liberaal ‘in de zin dat hij voor politieke en burgerlijke vrijheid staat, voor constitutionalisme, humanisme, tolerantie, matiging, internationalisme en machtsdeling en hij een afkeer heeft van absolutisme. Al deze aspecten zijn echter voor hem slechts voorwaarden voor een erotisch bestaan, voor humanisering, verfijning en verheffing.’

Als kind van zijn tijd kan Montesquieu bezwaarlijk een Europees federalist zijn, maar hij bepleit de humanisering van de verhouding tussen staten en bevolkingen en hecht daarbij veel belang aan vrijhandel en het machtsevenwicht tussen onderling afhankelijke staten. Dit kan een einde maken aan de permanente confrontatie, en de burger beschermen tegen misbruik van gezag, betoogt Frederik Dhondt in zijn bijdrage.

Zo biedt dit boek menig verrassend inzicht, waarop ik hier niet kan ingaan. Ook kan de lezer nader kennismaken met de fameuze Perzische Brieven, anoniem verschenen roman in briefvorm, een puntige satire op het absolutistische Frankrijk, die ook voor de hedendaagse lezer een eyeopener kan zijn. Montesquieu toont zich hier en elders een helder waarnemer, niet beïnvloed door modedenken, niet geneigd mee te huilen met de goegemeente, kritisch over de katholieke clerus, fel tegen de inquisitie en verwoed tegenstander van de slavernij.

Ten slotte: De l’Esprit kan niet begrepen worden zonder er de klimaattheorie van de auteur bij te betrekken. Het klimaat is voor Montesquieu en veel van zijn tijdgenoten namelijk de belangrijkste van alle invloeden op het leven van de mens. Maar diezelfde mens kan naar de overtuiging van de Franse denker door oordeelkundig handelen de invloed van het klimaat bijsturen, zo troost Patrick Stouthuysen de mogelijk verontruste lezer.

00:05 Publié dans Livre, Livre, Philosophie, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : montesquieu, 18ème siècle, lumières, philosophie des lumières, esprit des lois, livre, philosophie, philosophie politique, théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 20 mai 2013

The Enlightenment from a New Right Perspective

The Enlightenment from a New Right Perspective

By Domitius Corbulo

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

“When Kant philosophizes, say on ethical ideas, he maintains the validity of his theses for men of all times and places. He does not say this in so many words, for, for himself and his readers, it is something that goes without saying. In his aesthetics he formulates the principles, not of Phidias’s art, of Rembrandt’s art, but of Art generally. But what he poses as necessary forms of thought are in reality only necessary forms of Western thought.” — Oswald Spengler

“Humanity exists in its greatest perfection in the white race.” — Immanuel Kant

Every one either praises or blames the Enlightenment for the enshrinement of equality and cosmopolitanism as the moral pillars of our times. This is wrong. Enlightenment thinkers were racists who believe that only white Europeans could be fully rational, good citizens, and true cosmopolitans.

Leftists have brought attention to some racist beliefs among Enlightenment thinkers, but they have not successfully shown that racism was an integral part of Enlightenment philosophy, and their intention has been to denigrate the Enlightenment for representing the parochial values of European males. I argue here that they were the first to introduce a scientific conception of human nature structured by racial classifications. This conception culminated in Immanuel Kant’s anthropological justification of the superior/inferior classification of “races of men” and his “critical” argument that only European peoples were capable of becoming rational and free legislators of their own actions. The Enlightenment is a celebration of white reason and morality; therefore, it belongs to the New Right.

In an essay [2] in the New York Times (February 10, 2013), Justin Smith, another leftist with a grand title, Professeur des Universités, Département d’Histoire et Philosophie des Sciences, Université Paris Diderot – Paris VII, contrasted the intellectual “legacy” of Anton Wilhelm Amo, a West African student and former slave who defended a philosophy dissertation at the University of Halle in Saxony in 1734, with the “fundamentally racist” legacy of Enlightenment thinkers. Smith observed that a dedicatory letter was attached to Amo’s dissertation from the rector of the University of Wittenberg, Johannes Kraus, praising the “natural genius” of Africa and its “inestimable contribution to the knowledge of human affairs.” Smith juxtaposed Kraus’s broad-mindedness to the prevailing Enlightenment view “lazily echoed by Hume, Kant, and so many contemporaries” according to which Africans were naturally inferior to whites and beyond the pale of modernity.

Smith questioned “the supposedly universal aspiration to liberty, equality and fraternity” of Enlightenment thought. These values were “only ever conceived” for a European people deemed to be superior and therefore more equal than non-whites. He cited Hume: “I am apt to suspect the Negroes, and in general all other species of men to be naturally inferior to the whites.” He also cited Kant’s dismissal of a report of something intelligent that had once been uttered by an African: “this fellow was quite black from head to toe, a clear proof that what he said was stupid.” Smith asserted that it was counter-Enlightenment thinkers, such as Johann Herder, who would formulate anti-racist views in favor of human diversity. In the rest of his essay, Smith pondered why Westerners today “have chosen to stick with categories inherited from the century of the so-called Enlightenment” even though “since the mid-20th century no mainstream scientist has considered race a biologically significant category; no scientist believes any longer that ‘negroid,’ ‘caucasoid,’ and so on represent real natural kinds.” We should stop using labels that merely capture “something as trivial as skin color” and instead appreciate the legacy of Amo as much as that of any other European in a colorblind manner.

Smith’s article, which brought some 370 comments, a number from Steve Sailer, was challenged a few days later by Kenan Malik, ardent defender of the Enlightenment, in his blog Pandaemonium [3]. Malik’s argument that Enlightenment thinkers “were largely hostile to the idea of racial categorization” represents the general consensus on this question. Malik is an Indian-born English citizen, regular broadcaster at BBC, and noted writer for The Guardian, Financial Times, The Independent, Sunday Times, New Statesman, Prospect, TLS, The Times Higher Education Supplement, and other venues. Once a Marxist, Malik is today a firm defender of the “universalist ideas of the Enlightenment,” freedom of speech, secularism, and scientific rationalism. He is best known for his strong opposition to multiculturalism.

Yet this staunch opponent of multiculturalism is a stauncher advocate of open door policies on immigration [4]. In one of his TV documentaries, tellingly titled Let ‘Em All In (2005), he demanded that Britain’s borders be opened to the world without restrictions. In response to a report published during the post-Olympic euphoria in Britain, “The Melting Pot Generation: How Britain became more relaxed about race [5],” he wrote: “news that those of mixed ethnicity are among the fastest-growing groups in the population is clearly to be welcomed [6].” He added that much work remains to be done “to change social perceptions of race.”

This work includes fighting against any immigration objection even from someone like David Goodhart, director of the left think tank Demos, whose just released book, The British Dream [7], modestly made the observation that immigration is eroding traditional identities and creating an England “increasingly full of mysterious and unfamiliar worlds.” In his review (The Independent [8], April 19, 2013) Malik insisted that not enough was being done to wear down the traditional identities of everyone including the native British. The solution is more immigration coupled with acculturation to the universal values of the Enlightenment. “I am hostile to multiculturalism not because I worry about immigration but because I welcome it.” The citizens of Britain must be asked to give up their ethnic and cultural individuality and make themselves into universal beings with rights equal to every newcomer.

It is essential, then, for Malik to disassociate the Enlightenment with any racist undertones. This may not seem difficult since the Enlightenment has consistently come to be seen — by all political ideologies from Left to Right — as the source of freedom, equality, and rationality against the “unreasonable and unnatural” prejudices of particular cultural groups. Malik acknowledges that in recent years some (he mentions George Mosse, Emmanuel Chuckwude Eze, and David Theo Goldberg) have blamed Enlightenment thinkers for articulating the modern idea of race and projecting a view of Europe as both culturally and racially superior. By and large, however, Malik manages (superficially speaking) to win the day arguing that the racist statements one encounters in some Enlightenment thinkers were marginally related to their overall philosophies.

A number of thinkers within the mainstream of the Enlightenment . . . dabbled with ideas of innate differences between human groups . . . Yet, with one or two exceptions, they did so only diffidently or in passing.

The botanist Carolus Linnaeus exhibited the cultural prejudices of his time when he described Europeans as “serious, very smart, inventive” and Africans as “impassive, lazy, ruled by caprice.” But let’s us not forget, Malik reasons, that Linnaeus’ Systema Naturae “is one of the landmarks of scientific thought,” the first “distinctly modern” classification of plants and animals, and of humans in rational and empirical terms as part of the natural order. The implication is that Linnaeus could not have offered a scientific classification of nature while seriously believing in racial differences. Science and race are incompatible.

Soon the more progressive ideas of Johann Blumenbach came; he complained about the prejudices of Linnaeus’ categories and called for a more objective differentiation between human groups based on skull shape and size. It is true that out of Blumenbach’s five-fold taxonomy (Caucasians, Mongolians, Ethiopians, Americans and Malays) the categories of race later emerged. But Malik insists that “it was in the 19th, not 18th, century that a racial view of the world took hold in Europe.”

Malik mentions Jonathan Israel’s argument that there were two Enlightenments, a mainstream one coming from Kant, Locke, Voltaire and Hume, and a radical one coming from “lesser known figures such as d’Holbach, Diderot, Condorcet and Spinoza.” This latter group pushed the ideas of reason, universality, and democracy “to their logical conclusion,” nurturing a radical egalitarianism extending across class, gender, and race. But, in a rather confusing way and possibly because he could not find any discussions of race in the radical group to back up his argument, Malik relies on the mainstream group. He cites David Hume: “It is universally acknowledged that there is a great uniformity among the acts of men, in all nations and ages, and that human nature remains the same in its principles and operations.” And George-Louis Buffon, the French naturalist: “Every circumstance concurs in proving that mankind is not composed of species essentially different from each other.” While Enlightenment thinkers asked why there was so much cultural variety across the globe, Malik explains, “the answer was rarely that human groups were racially distinct . . . environmental differences and accidents of history had shaped societies in different ways.” Remedying these differences and contingencies was what the Enlightenment was about; as Diderot wrote, “everywhere a people should be educated, free, and virtuous.”

Malik’s essay is pedestrian, somewhat disorganized, but in tune with the established literature, and therefore seen by the public as a compilation of truisms against marginal complaints about racism in the Enlightenment. Almost all the books on the Enlightenment have either ignored this issue or addressed it as a peripheral theme. The emphasis has been, rather, on the Enlightenment’s promotion of universal values for the peoples of the world. Let me offer some examples. Leonard Krieger’s King and Philosopher, 1689–1789 (1970) highlights the way the Enlightenment produced “works in which the universal principles of reason were invoked to order vast reaches of the human experience,” Rousseau’s “anthropological history of the human species,” Hume’s “quest for uniform principles of human nature,” “the various tendencies of the philosophes’ thinking — skepticism, rationalism, humanism, and materialism” (152-207). Peter Gay’s The Enlightenment: An Interpretation (1966) is altogether about how “the men of the Enlightenment united on . . . a program of secularism, humanity, cosmopolitanism, and freedom . . . In 1784, when the Enlightenment had done most of its work, Kant defined it as man’s emergence from his self-imposed tutelage, and offered as its motto: Dare to know” (3). Norman Hampson’s The Enlightenment (1968) spends more time on the proponents of modern classifications of nature, particularly Buffon’s Natural History, but makes no mention of racial classifications or arguments opposing any notion of a common humanity.

Recent books are hardly different. Louis Dupre’s The Enlightenment and the Intellectual Foundations of Modern Culture (2004), traces our current critically progressive attitudes back to the Enlightenment “ideal of human emancipation.” Dupré argues (from a perspective influenced by Jurgen Habermas) that the original project of the Enlightenment is linked to “emancipatory action” today (335). Gertrude Himmelfarb’s The Roads to Modernity: The British, French, and American Enlightenments (2004), offers a neoconservative perspective of the British and the American “Enlightenments” contrasted to the more radical ideas of human perfectibility and the equality of mankind found in the French philosophes. She brings up Jefferson’s hope that in the future whites would “blend together, intermix” and become one people with the Indians (221). She quotes Madison on the “unnatural traffic” of slavery and its possible termination, and also Jefferson’s proposal that the slaves should be freed and sent abroad to colonize other lands as “free and independent people.” She implies that Jefferson thought that sending blacks abroad was the most humane solution given the “deep-rooted prejudices of whites and the memories of blacks of the injuries they had sustained” (224).

Recent books are hardly different. Louis Dupre’s The Enlightenment and the Intellectual Foundations of Modern Culture (2004), traces our current critically progressive attitudes back to the Enlightenment “ideal of human emancipation.” Dupré argues (from a perspective influenced by Jurgen Habermas) that the original project of the Enlightenment is linked to “emancipatory action” today (335). Gertrude Himmelfarb’s The Roads to Modernity: The British, French, and American Enlightenments (2004), offers a neoconservative perspective of the British and the American “Enlightenments” contrasted to the more radical ideas of human perfectibility and the equality of mankind found in the French philosophes. She brings up Jefferson’s hope that in the future whites would “blend together, intermix” and become one people with the Indians (221). She quotes Madison on the “unnatural traffic” of slavery and its possible termination, and also Jefferson’s proposal that the slaves should be freed and sent abroad to colonize other lands as “free and independent people.” She implies that Jefferson thought that sending blacks abroad was the most humane solution given the “deep-rooted prejudices of whites and the memories of blacks of the injuries they had sustained” (224).

Dorinda Outram’s, The Enlightenment (1995) brings up directly the way Enlightenment thinkers responded to their encounters with very different cultures in an age characterized by extraordinary expeditions throughout the globe. She notes there “was no consensus in the Enlightenment on the definition of the races of man,” but, in a rather conjectural manner, maintains that “the idea of a universal human subject . . . could not be reconciled with seeing Negroes as inferior.” Buffon, we are safely informed, “argued that the human race was a unity.” Linnaeus divided humanity into different classificatory groups, but did so as members of the same human race, although he “was unsure whether pigmies qualified for membership of the human race.” Turgot and Condorcet believed that “human beings, by virtue of their common humanity, would all possess reason, and would gradually discard irrational superstitions” (55-8). Outram’s conclusion on this topic is typical: “The Enlightenment was trying to conceive a universal human subject, one possessed of rationality,” accordingly, it cannot be seen as a movement that stood against racial divisions (74). Roy Porter, in his exhaustively documented and opulent narrative, Enlightenment: Britain and the Creation of the Modern World (2000), dedicates less than one page of his 600+ page book to discourses on “racial differentiation.” He mentions Lord Kames as “one of many who wrestled with the evidence of human variety . . . hinting that blacks might be related to orang-utans and similar great apes.” Apart from this quaint passage, there is only this: “debate was heated and unresolved, and there was no single Enlightenment party line” (357).

In my essay, “Enlightenment and Global History [9],” I mentioned a number of other books which view the Enlightenment as a European phenomenon and, for this reason, have been the subject of criticism by current multicultural historians who feel that this movement needs to be seen as global in origins. I defended the Eurocentrism of these books while suggesting that their view of the Enlightenment as an acclamation of universal values (comprehensible and extendable outside the European ethnic homeland) was itself accountable for the idea that its origins must not be restricted to Europe. Multicultural historians have merely carried to their logical conclusion the allegedly universal ideals of the Enlightenment. The standard interpretations of Tzvetan Todorov’s In Defence of the Enlightenment (2009), Stephen Bronner’s Reclaiming the Enlightenment (2004), and Robert Louden’s, The World We Want: How and Why the Ideals of the Enlightenment Still Eludes Us (2007), equally neglect the intense interest Enlightenment thinkers showed in the division of humanity into races. They similarly pretend that, insomuch as these thinkers spoke of “reason,” “humanity,” and “equality,” they were thinking outside or above the European experience and intellectual ancestry.

What about Justin Smith, or, since he has not published in this field, the left liberal authors on this topic? There is not that much; the two best known sources are two anthologies of writings on race, namely, Race and the Enlightenment: A Reader (1997), edited by Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze; and The Idea of Race (2000), edited by Robert Bernasconi and Tommy Lott. Eze’s book gathers into a short book the most provocative writings on race by some Enlightenment thinkers (Hume, Linnaeus, Kant, Buffon, Blumenbach, Jefferson and Cuvier). This anthology, valuable as it is, is intended for effect, to show how offensively racist these thinkers were. Eze does not disprove the commonly accepted idea that Enlightenment thinkers were proponents of a universal ethos (although, as we will see below, Eze does offer elsewhere a rather acute analysis of Kant’s racism). Bernasconi’s The Idea of Race is mostly a collection of nineteenth and 20th century writings, with short excerpts from Francois Bernier, Voltaire, Kant, and Blumenbach. The books that Malik mentions (see above) which connect the Enlightenment to racism are also insufficient: George Mosse’s Toward the Final Solution: A History of European Racism (1985) is just another book about European anti-Semitism, which directs culpability to the Enlightenment for carrying classifications and measurements of racial groups. David Goldberg’s Racist Culture (1993) is a study of the normalization of racialized discourses in the modern West in the 20th century.

There are, as we will see later, other publications which address in varying ways this topic, but, on the whole, the Enlightenment is normally seen as the most critical epoch in “mankind’s march” towards universal brotherhood. The leftist discussion of racist statements relies on the universal principles of the Enlightenment. Its goal is to uncover and challenge any idea among 18th century thinkers standing in the way of a future universal civilization. Leftist critics enjoy “exposing” white European males as racists and thereby re-appropriate the Enlightenment as their own from a cultural Marxist perspective. But what if we were to approach the racism and universalism of the Enlightenment from a New Right perspective that acknowledges straightaway the particular origins of the Enlightenment in a continent founded by Indo-European [10] speakers?

This would involve denying the automatic assumption that the ideas of the philosophes were articulated by mankind and commonly true for every culture. How can the ideas of the Enlightenment be seen as universal, representing the essence of humanity, if they were expressed only by European men? The Enlightenment is a product of Europe alone, and this fact alone contradicts its universality. Enlightenment thinkers are themselves to blame for this dilemma expressing their ideas as if “for men of all times and places.” Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803), writing at the same time as Kant, did question the notion of a cosmopolitan world based on generic human values. He saw in the world the greatest possible variety of historical humans in different regions of the earth, in time and space. He formulated arguments against racial rankings not by questioning their scientific merits as much as their reduction of the diversity of humans to one matrix of measurement and judgment. It was illusory to postulate a universal philosophy for humanity in which the national character of peoples would disappear and each human on earth would “love each other and every one . . . being all equally polite, well-mannered and even-tempered . . . all philanthropic citizens of the world.”[1] Contrary to some interpretations, Herder was not rejecting the Enlightenment but subjecting it to critical evaluation from his own cosmopolitan education in the history and customs of the peoples of the earth. “Herder was among the men of the Enlightenment who were critical in their search for self-understanding; in short, he was part of the self-enlightening Enlightenment.”[2] He proposed a different universalism based on the actual variety and unique historical experiences and trajectories of each people (Volk). Every people had their own particular language, religion, songs, gestures, legends and customs. There was no common humanity but a division of peoples into language and ethnic groups. Each people were capable of achieving education and progress in its own way from its own cultural sources.

From this standpoint, the Enlightenment should be seen as an expression of a specific people, Europeans, made up of various nationalities but nevertheless in habitants of a common civilization who were actually conceiving the possibility of becoming good citizens of Europe at large. In the words of Edward Gibbon, Enlightenment philosophers were enlarging their views beyond their respective native countries “to consider Europe as a great republic, whose various inhabitants have attained almost the same level of politeness and cultivation” (in Gay, 13).

Beyond Herder, we also need to acknowledge that the Enlightenment inaugurated the study of race from a rational, empirical, and secular perspective consistent with its own principles. No one has been willing to admit this because this entire debate has been marred by the irrational, anti-Enlightenment dogma that race is a construct and that the postulation of a common humanity amounts to a view of human nature without racial distinctions. Contrary to Roy Porter, there was a party line, or, to be more precise, a consistently racial approach among Enlightenment thinkers. The same philosophes who announced that human nature was uniform everywhere, and united mankind as a subject capable of enlightenment, argued “in text after text . . . in the works of Hume, Diderot, Montesquieu, Kant, and many lesser lights” that men “are not uniform but are divided up into sexes, races, national characters . . . and many other categories” (Garret 2006). But because we have been approaching Enlightenment racism under the tutelage of our current belief that race is “a social myth” and that any division of mankind into races is based on malevolent “presumptions unsupported by available evidence [11],” we have failed to appreciate that this subject was part and parcel of what the philosophes meant by “enlightenment.” Why it is so difficult to accept the possibility that 18th century talk about “human nature” and the “unity of mankind” was less a political program for a universal civilization than a scientific program for the study of man in a way that was systematic in intent and universal in scope? It is quite legitimate, from a scientific point, to treat humans everywhere as uniformly constituted members of the same species while recognizing their racial and cultural variety across the world. Women were considered to be intrinsically different from men at the same time that they were considered to be human.

Not being an expert on the Enlightenment I found recently a book chapter titled “Human Nature” by Aaron Garrett in a two volume work, The Cambridge History of Eighteenth-Century Philosophy [12] (2006). There is a section in this chapter dealing with “race and natural character”; it is short, 20 pages in a 1400 page work, but it is nevertheless well researched with close to 80 footnotes of mostly primary sources. One learns from these few pages that “in text after text” Enlightenment thinkers proposed a hierarchical view of the races. Mind you, Garrett is stereotypically liberal and thus writes of “the 18th century’s dubious contributions to the discussion of race,” startled by “the virulent denigrations of blacks . . . found in the works of Franklin, Raynal, Voltaire, Forster, and many others.” He also playacts the racial ideas of these works as if they were inconsistent with the scientific method, and makes the very unscientific error of assuming that there was an “apparent contradiction” with the Enlightenment’s notion of a hierarchy of races and its “vigorous attacks on the slave trade in the name of humanity.”

Just because most Enlightenment thinkers rejected polygenecism and asserted the fundamental (species) equality of humankind, it does not mean that they could not believe consistently in the hierarchical nature of the human races. There were polygenecists like Charles White who argued that blacks formed a race different from whites, and Voltaire who took some pleasure lampooning the vanity of the unity of mankind. But the prevailing view was that all races were members of the same human species, as all humans were capable of creating fertile offspring. Buffon, Cornelius de Pauw, Linnaeus, Blumenbach, Kant and others endorsed this view, and yet they distinctly ranked whites above other races.

Liberals have deliberately employed this view on the species unity of humanity in order to separate, misleadingly, the Enlightenment from any racial connotations. But Linnaeus did rank the races in their behavioral proclivities; and Buffon did argue that all the races descended from an original pair of whites, and that American Indians and Africans were degraded by their respective environmental habitats. De Pauw did say that Africans had been enfeebled in their intelligence and “disfigured” by their environment. Samuel Soemmering did conclude that blacks were intellectually inferior; Peter Camper and John Hunter did rank races in terms of their facial physiognomy. Blumenbach did emphasize the symmetrical balance of Caucasian skull features as the “most perfect.” Nevertheless, in accordance with the evidence collected at the time, all these scholars asserted the fundamental unity of mankind, monogenism, or the idea that all races have a common origin.

Garrett, seemingly unable to accept his own “in text after text” observation, repeats the standard line that Buffon’s and Blumenbach’s view, for example, on “the unity and structural similarity of races” precluded a racial conception. He generally evades racist phrases and arguments from Enlightenment thinkers, such as this one from Blumenbach: “I have allotted the first place to the Caucasian because this stock displays the most beautiful race of men” (Eze, 1997: 79). He makes no mention or almost ignores a number of other racialists [13]: Locke, Georges Cuvier, Johann Winckelmann, Diderot, Maupertuis, and Montesquieu. In the case of Kant, he says it would be “absurd” to take some “isolated remarks” he made about race as if they stood for his whole work. Kant “distinguish between character, temperament, and race in order to avoid biological determinism” for the sake of the “moral potential of the human race as a whole.”

Actually, Kant, the greatest thinker of the Enlightenment, “produced the most profound raciological thought of the 18th century.” These words come from Earl W. Count’s book This is Race, cited by Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze in what is a rather good analysis of Kant’s racism showing that it was not marginal but deeply embedded in his philosophy. Eze’s analysis comes in a chapter, “The Color of Reason: The Idea of ‘Race’ in Kant’s Anthropology [14]” (1997). We learn that Kant elaborated his racial thinking in his Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View [15] (1798); he introduced anthropology as a branch of study to the German universities together with the study of geography, and that through his career Kant offered 72 courses in Anthropology and/or Geography, more than in logic, metaphysics and moral philosophy. Although various scholars have shown interest in Kant’s anthropology, they have neglected its relation to Kant’s “pure philosophy.”

Actually, Kant, the greatest thinker of the Enlightenment, “produced the most profound raciological thought of the 18th century.” These words come from Earl W. Count’s book This is Race, cited by Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze in what is a rather good analysis of Kant’s racism showing that it was not marginal but deeply embedded in his philosophy. Eze’s analysis comes in a chapter, “The Color of Reason: The Idea of ‘Race’ in Kant’s Anthropology [14]” (1997). We learn that Kant elaborated his racial thinking in his Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View [15] (1798); he introduced anthropology as a branch of study to the German universities together with the study of geography, and that through his career Kant offered 72 courses in Anthropology and/or Geography, more than in logic, metaphysics and moral philosophy. Although various scholars have shown interest in Kant’s anthropology, they have neglected its relation to Kant’s “pure philosophy.”

For Kant, anthropology and geography were inseparable; geography was the study of the natural conditions of the earth and of man’s physical attributes and location as part of this earth; whereas anthropology was the study of man’s soul, his psychological and moral character, as exhibited in different places on earth. In his geography Kant addressed racial classifications on the basis of physical traits such as skin color; in his anthropology he studied the internal structures of human psychology and the manner in which these internal attributes conditioned humans as moral and rational beings.

Kant believed that human beings were different from other natural beings in their capacity for consciousness and agency. Humans were naturally capable of experiencing themselves as self-reflecting egos capable of acting morally on the basis of their own self-generated norms (beyond the determinism which conditioned all other beings in the universe). It is part of our internal human nature to think and will as persons with moral agency. This uniquely human attribute is what allows humans to transcend the dictates of nature insofar as they are able to articulate norms as commandments for their own actions freed from unconscious physical contingencies and particular customs. As rational beings, humans are capable of creating a realm of ends, and these ends are a priori principles derived not from the study of geography and anthropology but from the internal structures of the mind, transcendental reason. What Kant means by “critical reason” is the ability of humans through the use of their minds to subject everything (bodily desires, empirical reality, and customs) to the judgments of values generated by the mind, such that the mind (reason) is the author of its own moral actions.

However, it was Kant’s estimation that his geographical and anthropological studies gave his moral philosophy an empirical grounding. This grounding consisted in the acquisition of knowledge about human beings “throughout the world,” to use Kant’s words, “from the point of view of the variety of their natural properties and the differences in that feature of the human which is moral in character.”[3] [16] Kant was the first thinker to sketch out a geographical and psychological (or anthropological) classification of humans. He classified humans naturally and racially into white (European), yellow (Asians), black (Africans) and red (American Indians). He also classified them psychologically and morally in terms of the mores, customs and aesthetic feelings held collectively by each of the races. Non-Europeans held unreflective mores and customs devoid of critical examination “because these people,” in the words of Eze, “lack the capacity for development of ‘character,’ and they lack character presumably because they lack adequate self-consciousness and rational will.” Within Kant’s psychological classification, non-Europeans “appear to be incapable of moral maturity because they lack ‘talent,’ which is a ‘gift’ of nature.” Eze quotes Kant: “the difference in natural gifts between various nations cannot be completely explained by means of causal [external, physical, climatic] causes but rather must lie in the [moral] nature of man.” The differences among races are permanent and transcend environmental factors. “The race of the American cannot be educated. It has no motivating force; for it lacks affect and passion . . . They hardly speak, do not caress each other, care about nothing and are lazy.” “The race of the Negroes . . . is completely the opposite of the Americans; they are full of affect and passion, very lively, talkative and vain. They can be educated but only as servants . . . ” The Hindus “have a strong degree of passivity and all look like philosophers. They thus can be educated to the highest degree but only in the arts and not in the sciences. They can never arise to the level of abstract concepts . . . The Hindus always stay the way they are, they can never advance, although they began their education much earlier.”

Eze then explains that for Kant only “white” Europeans are educable and capable of progress in the arts and sciences. They are the “ideal model of universal humanity.” In other words, only the European exhibits the distinctly human capacity to behave as a rational creature in terms of “what he himself is willing to make himself” through his own ends. He is the only moral character consciously free to choose his own ends over and above the determinism of external nature and of unreflectively held customs. Eze, a Nigerian born academic, obviously criticizes Kant’s racism, citing and analyzing additional passages, including ones in which Kant states that non-Europeans lack “true” aesthetic feelings. He claims that Kant transcendentally hypostasized his concept of race simply on the basis of his belief that skin color by itself stands for the presence or absence of the natural ‘gift’ of talent and moral ‘character’. He says that Kant’s sources of information on non-European customs were travel books and stories he heard in Konigsberg, which was a bustling international seaport. Yet, this does not mean that he was simply “recycling ethnic stereotypes and prejudices.” Kant was, in Eze’s estimation, seriously proposing an anthropological and a geographical knowledge of the world as the empirical presupposition of his critical philosophy.

With the publication of this paper (and others in recent times) it has become ever harder to designate Kant’s thinking on race as marginal. Thomas Hill and Bernard Boxill dedicated a chapter, “Kant and Race [17],” to Eze’s paper in which they not only accepted that Kant expressed racist beliefs, but also that Eze was successful “in showing that Kant saw his racial theory as a serious philosophical project.” But Hill and Boxill counter that Kant’s philosophy should not be seen to be inherently “infected with racism . . . provided it is suitably supplemented with realistic awareness of the facts about racism and purged from association with certain false empirical beliefs.” These two liberals, however, think they have no obligation to provide their readers with one single fact proving that the races are equal. They don’t even mention a source in their favor such as Stephen J. Gould [18]. They take it as a given that no one has seriously challenged the liberal view of race but indeed assume that such a challenge would be racist ipso facto and therefore empirically unacceptable. They then excuse Kant on grounds that the evidence available in his time supported his claims; but that it would be racist today to make his claims for one would be “culpable” of neglecting the evidence that now disproves racial classifications. What evidence [19]?

They then argue that “racist attitudes are incompatible with Kant’s basic principle of respect for humanity in each person,” and in this vein refer to Kant’s denunciation, in his words, of the “wars, famine, insurrection, treachery and the whole litany of evils” which afflicted the peoples of the world who experience the “great injustice of the European powers in their conquests.” But why do liberals always assume that claims about racial differences constitute a call for the conquest and enslavement of non-whites? They forget the 100 million killed in Russia and China, or, conversely, the fact that most Enlightenment racists were opponents of the slave trade. The bottom logic of the Hill-Boxill counterargument is that Kant’s critical philosophy was/is intrinsically incompatible with any racial hierarchies which violate the principles of human freedom and dignity, even if his racism was deeply embedded in his philosophy. But it is not; and may well be the other way around; Kant’s belief in human perfectibility, the complete development of moral agency and rational freedom, may be seen as intrinsically in favor of a hierarchical way of thinking in terms of which race is the standard bearer of the ideal of a free and rational humanity.

It is quite revealing that an expert like Garrett, and the standard interpreters of the Enlightenment generally, including your highness Doctor Habermas, would ignore Kant’s anthropology. A recent essay by Stuart Elden, “Reassessing Kant’s geography [20]” (2009), examines the state of this debate, noting that Kant’s geography and anthropology are still glaringly neglected in most newer works on Kant. One reason for this, Elden believes, “is that philosophers have, by and large, not known what to make of the works.” I would specify that they don’t know what to make of Kant’s racism in light of the widely accepted view that he was a liberal progenitor of human equality and cosmopolitanism. Even Elden does not know what to make of this racism, though he brings attention to some recent efforts to incorporate fully Kant’s anthropology/geography into his overall philosophy, works by Robert Louden, Kant’s Impure Ethics (2000); John Zammito, Kant, Herder, and the Birth of Anthropology (2002), and Holly Wilson, Kant’s Pragmatic Anthropology (2006). Elden pairs off these standard (pro-Enlightenment, pro-Kant) works against the writings of leftist critics who have shown less misgivings designating Kant a racist. All of these works (leftists as well) are tainted by their unenlightened acceptance of human equality and universalism. They cannot come to terms with a Kant who proposed a critical philosophy only for the European race.