mercredi, 20 janvier 2021

Idéologie des Lumières et progressisme

Idéologie des Lumières et progressisme

Par Alberto Buela

Ex : https://www.posmoderna.com

C'est finalement l'œuvre du philosophe allemand Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) Was ist Aufklärung ? (1784) qui a le mieux défini ce qu'était le Siècle des Lumières lorsqu'il a déclaré : "c'est la libération de l'homme de la minorité qu’il s’est imposé". C'est-à-dire de son incapacité à faire usage de la seule raison sans dépendre d'une autre tutelle, comme l'était la théologie au Moyen-Âge, où l'on disait : philosophia ancilla teologíae = la philosophie est la servante de la théologie.

La devise des Lumières était Sapere aude, « oser savoir », en utilisant sa propre raison.

Mais les Lumières, cherchant à émanciper l'homme de la théologie, des préjugés et des superstitions, finirent par déifier "La Raison" et ses produits : technique et calcul dont les conséquences furent contradictoires, puisque son plus grand travail fut la bombe atomique d'Hiroshima et de Nagasaky.

Après avoir été à un poste de combat à sa mesure, l'homme était à nouveau considéré comme une île rationnelle mais entourée d'une mer d'irrationalités, comme aimait à le dire Ortega. La sagesse pré-moderne est à nouveau prise en compte. Des aspects fondamentaux de l'homme qui avaient été négligés par le Siècle des Lumières et ses adeptes, et qui appartenaient au Moyen Âge diabolisé, ont été lentement repris en compte. L'homme postmoderne se plonge à nouveau dans les eaux des problèmes éternels. Mais, bien sûr, avec une différence abyssale : c'est un homme sans foi, sans espoir, nihiliste. Ainsi naquit la pensée d'un Vattimo, une pensée faible (pensiero debole) qui peut donner des raisons à l'état actuel de l'être humain mais qui ne peut donner de sens aux actions à entreprendre pour sortir du bourbier actuel.

Cependant, une grande partie du monde intellectuel de l'après-guerre, notamment celui qui fut lié au marxisme, au communisme et au socialisme, a continué sur la voie des Lumières, même si l'école de Francfort, quintessence de la pensée juive contemporaine (Weil, Lukacs, Grünberg, Horkheimer, Adorno, Marcuse, Fromm), Habermas et alii) qui a soutenu, en synthèse, que nous avions tort non pas parce que les produits du rationalisme éclairé avaient montré leurs flagrantes contradictions en faisant le mal à des innocents comme cela s'est produit avec les milliers de Japonais nés radioactifs et condamnés d'avance, mais parce que les postulats des Lumières n'avaient pas été pleinement appliqués.

Les vainqueurs de la Seconde Guerre mondiale ont adapté, avec des variantes social-démocratiques ou néo-libérales, les restes de la pensée des Lumières, qui ont traversé les ‘’eaux du Jourdain’’, c’est-à-dire les méandres de l'école de Francfort, laquelle possédait la boussole culturelle de notre époque. Ainsi, son produit le plus réussi est le progressisme actuel.

C'est pour cette raison qu'un de nos très bons collègues déclare : "Peut-être est-il correct de dire que le progressisme est ce qui reste du marxisme après son échec historique en tant qu'option politique, économique et sociale et sa résignation transitoire (ou définitive ?) face au triomphe du capitalisme. Une sorte de retour en arrière, en sautant par-dessus le bolchevisme, vers le réformisme de la social-démocratie" [1]. Le progressisme a adopté comme devise "ne pas être vieux et toujours être à l'avant-garde". Comme nous le voyons, la résonance avec les Lumières est évidente.

Que partage le progressisme, à son tour, avec le néolibéralisme : 1) l'adoption de la démocratie libérale, rebaptisée discursive, consensuelle, inclusive, droits de l'hommiste, etc. 2) l'économie de marché, malgré son discours contre les groupes concentrés, etc. 3) l'homogénéisation culturelle planétaire, au-delà de son discours sur le multiculturalisme. Le progressisme est la voie moderne vers la mondialisation

Le progressisme est ainsi, en fin de compte, parce qu'il croit à l'idée de progrès. En réalité, le progressisme n'est pas une idéologie mais plutôt une croyance, car, comme Ortega y Gasset aimait à le dire, les idées sont simplement proclamées et les croyances nous soutiennent, car dans les croyances "on est". Et les progressistes "croient" que l'homme, le monde et ses problèmes vont dans la direction où ils vont. Ainsi, tout contrevenant à leurs croyances est considéré comme "un ennemi". L'être progressiste qui est un ‘’croyant’’ n'accepte pas d'appréhender le réel danssonâpreté, et le seul enseignement qu'il accepte, parce que son imposition devient incontestable, est la pédagogie de la catastrophe. Il découvre ainsi qu'il y a des milliers de pauvres et de chômeurs lorsqu'une inondation se produit et que les ordinateurs promus ne fonctionnent pas parce que dans les écoles rurales il n'y a pas d'électricité ou pas de réseau.

En bref, le progressisme et les Lumières partagent la conviction que la réalité est ce qu'ils pensent qu'elle est et non pas, que la réalité est la vérité de la chose ou de la matière.

Le grand courant qui contredit le progressisme est le soi-disant réalisme politique (R. Niebuhr, J. Freund, C. Schmitt, R. Aron, H. Morgenthau, G. Miglio, D. Negro Pavón) qui assume avec scepticisme les projets théoriques qui formulent la possibilité d'une paix perpétuelle, d'une organisation parfaite de la société dans le cadre d'un progrès illimité. Et ce réalisme comprend l'histoire comme le résultat d'une tendance naturelle de l'homme à convoiter le pouvoir et la domination des autres.

Le réalisme politique vient remplacer l'homo homini sacra res = l'homme est quelque chose de sacré pour l'homme, qui remonte à Sénèque, par l'homo homini lupus = l'homme est un loup de l'homme de Hobbes, qui a repris cette vue à Plaute.

Le réalisme politique affirme qu'il faut travailler sur la base des matériaux dont on dispose, et la réalité est ce qui en offre le plus, tandis que le progressisme affirme qu'il faut travailler sur ce en quoi on croit, puisque les idées s'imposent finalement à la réalité.

Le réalisme politique privilégie l'existence, tandis que le progressisme privilégie l'essence par rapport à l'existence.

[1]Maresca, Silvio: El retorno del progresismo,(2006) sur internet.

11:30 Publié dans Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, philosophie politique, alberto buela, progressisme, aufklärung, idéologie des lumières |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 18 novembre 2017

Robert Steuckers : Discours de Rotterdam, 14 octobre 2017

Robert Steuckers :

Discours de Rotterdam, 14 octobre 2017

Retrouver un âge d’or ?

Traduction française du script néerlandais

Si nous voulons, comme le titre de ce colloque l’indique, retrouver un âge d’or, ce sera bien entendu un âge d’or en concordance avec nos véritables racines et non pas un âge d’or qui serait le produit quelconque d’une forme ou une autre d’ingénierie sociale ; ce sera donc un âge d’or qui constituera un retour à des sources vives sans être simultanément un rejet du progrès technique et/ou scientifique, surtout pas sur le plan militaire. Ce retour sera donc bel et bien de facture « archéofuturiste » où l’avenir de nos peuples sera déterminé par des valeurs éternelles et impassables qui ne contrecarreront pas l’audace technicienne. Retourner à un âge d’or signifie donc réinsuffler de la vie à des valeurs-socles qui remontent au moins à la « période axiale de l’histoire » (ou « Moment Axial ») ou, même, qui remontent à plus loin dans le temps et ont façonné l’esprit d’ancêtres plus anciens encore.

On pourra appeler l’ensemble de ces valeurs « Tradition » ou non, elles constituent de toutes les façons, le fond propre de notre civilisation. On peut poser comme vrai qu’elles ont des racines plus profondes que les pseudo-valeurs des soi-disant Lumières, trop souvent insipides et devenues perverses au fil des décennies. Et si nous considérons les « Lumières » comme le véhicule intellectuel d’un flot de perversités, nous entendons désigner ainsi, avant tout, le progressisme actuel qui fonctionne comme un instrument et qui n’a plus qu’un seul but : éradiquer les valeurs anciennes, immémoriales, et les valeurs du « Moment Axial ». L’élimination de ces valeurs nous empêche d’avoir un avenir car, tout simplement, les peuples qui n’ont plus de valeurs en eux, en leur intériorité collective, errent et s’agitent totalement désorientés et perdent leurs capacités à façonner le politique (n’ont plus de Gestaltungskraft politique).

Pour paraphraser Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, qui écrivait dans les années 1920, je dirais que le libéralisme tue les peuples au bout de quelques décennies, s’ils suivent les règles que préconise cet ensemble de dispositifs idéologiques. Aujourd’hui, avec un vocabulaire nouveau, je dirais que toute idéologie reposant sur des simplifications exagérées tout en prétendant, de cette façon, avoir les « Lumières » comme source d’inspiration, étouffe la Gestaltungskraft politique des peuples. La France, l’Angleterre, partiellement les Etats-Unis et surtout l’Allemagne occidentalisée, sont aujourd’hui les exemples les plus emblématiques d’une involution de ce type.

Les Etats-Unis et l’Allemagne ont certes connu et connaissent encore un développement technique exceptionnel, ont atteint depuis la fin du 19ème siècle un niveau très élevé de technicité et de puissance technique mais, de nos jours, les indices s’accumulent pour montrer que leurs sociétés respectives vivent un déclin total et très préoccupant. En Allemagne, cette involution va de pair avec l’application systématique d’une stratégie bien précise, celle de la Vergangenheitsbewältigung, sorte de réécriture du passé où celui-ci est toujours décrit et considéré comme la source du mal absolu. Et cela ne vaut pas seulement pour le passé national-socialiste. Ce processus constant d’autodénigrement joue lourdement sur l’estime de soi nationale et induit une acceptation totale de toutes les pratiques politiques et sociales permettant de saborder définitivement la société. La politique d’accueil des réfugiés, qu’a imposée Madame Merkel peut être considérée comme le point culminant de cette pratique perverse de négation de soi. Une pratique que les pays du Groupe de Visegrad ne sont pas prêts d’accepter sans discuter.

En France, on observe un démantèlement graduel de l’Etat fort, jadis vénéré par des générations de Français, depuis Bodin, Louis XIV et Colbert. Un Etat fort que De Gaulle voulait maintenir. Eric Zemmour a esquissé récemment et avec brio une histoire du « suicide français ». Ce suicide a partiellement été induit par un livre du début des années 1980, lequel a joué un rôle particulièrement perfide dans l’émergence d’une Vergangenheitsbewältigung spécifiquement française. Ce livre a pour titre L’idéologie française et est issu de la plume du célèbre Bernard-Henri Lévy. Dans ce livre, tous les courants politiques non libéraux et non sociaux-démocrates sont estampillés « fascistes », y compris certains aspects importants du paléo-communisme français, du gaullisme en général et même du personnalisme chrétien d’un idéologue pusillanime comme Emmanuel Mounier. Dans ce livre de Lévy nous découvrons tous les instruments de ce qu’un politologue néerlandais, spécialiste des questions françaises, Luk de Middelaar, a appelé avec justesse le « politicide ».

Dans l’Allemagne d’après-guerre, les « Lumières » (Aufklärung) ont été posées comme le courant philosophique qui devait immuniser les Allemands et, dans la foulée, tous les autres Européens contre le mal politique en soi. Jürgen Habermas deviendra ainsi le théoricien par excellence de ces nouvelles Lumières ouest-allemandes qui devaient définitivement effacer les legs d’un mauvais passé.

Cependant, la vulgate des Lumières assénées par Habermas et traduites dans la pratique et le quotidien par une nuée de journalistes et de feuilletonistes zélés n’est jamais, finalement, qu’une vision tronquée des Lumières pour qui a réellement étudié l’histoire culturelle du 18ème siècle en Allemagne et en Europe. Le monde du 18ème et, a fortiori, celui que nous avons devant nous aujourd’hui, n’est pas aussi simpliste que le sieur Habermas et ses séides veulent bien l’admettre. Le « politiquement correct » fonctionne donc sur base d’une interprétation bâclée et bricolée de l’histoire des Lumières, lesquelles sont davantage plurielles.

Les Lumières, selon les adeptes de l’Ecole de Francfort et selon les fans de son élève modèle Habermas, sont certes un héritage plus ou moins légitime du 18ème siècle. Les Lumières, dans leur ensemble, ont cependant connu d’autres avatars, bien différents et bien plus féconds. Les Lumières d’aujourd’hui, politiquement correctes, ne sont finalement qu’une mauvaise combinaison de « blueprints » pour reprendre une expression de l’Anglais Edmund Burke lorsqu’il décrivait les dérives sanglantes de la révolution française. Burke n’est pourtant pas un obscurantiste ni l’adepte d’une scolastique vermoulue. Il critique la révolution française parce qu’elle articule une interprétation fausse des droits de l’homme. Il y a donc d’autres manières d’interpréter les droits de l’homme, surtout parce que l’Ancien Régime n’était pas un désert juridique et parce que les communautés concrètes y bénéficiaient de droits bien profilés.

Plus tard, dans les marges celtiques du Royaume-Uni, surtout dans la future République d’Irlande, émerge une interprétation particulière des droits de l’homme qui vise à offrir aux citoyens des droits, bien évidemment, sans nier l’esprit émancipateur des Lumières en général, mais sans pour autant renier les racines celtiques de la culture populaire. Dès lors, il s’agissait aussi de dégager les droits concrets des citoyens de tous les idéologèmes éradicateurs qui avaient vicié les Lumières et leur interprétation officielle dans notre Europe contemporaine. Après la seconde guerre mondiale, des juristes et des ministres irlandais ont fait condamner la République française en suivant tout à la fois les règles de l’ONU concernant les droits de l’homme et leurs propres réflexes panceltiques parce que Paris avait fait assassiner ou condamner des militants bretons. Ceux-ci avaient trouvé chez les Irlandais les avocats internationaux qu’il fallait. Remarquons au passage que le ministre McBride, qui fut l’un de ces avocats, est devenu ultérieurement le Président d’Amnesty International et Prix Nobel en 1974. La République qui, selon Lévy, est un système représentant la « rectitude politique » de la manière la plus emblématique, a donc été condamnée, dans les années 50, pour avoir foulé les droits de l’homme aux pieds !

Les Lumières selon Johann Gottfried Herder

Ensuite, puisque le thème de ce colloque est de baliser le retour éventuel à un nouvel âge d’or, il nous faut impérativement évoquer un fait historique, philosophique et littéraire que l’on a eu tendance à oublier ici en Europe continentale : les Lumières ne sont pas seulement celles que veut imposer Lévy car il y a aussi celles de Johann Gottfried Herder qui opère aujourd’hui un discret mais significatif retour dans les colonnes des meilleurs sites conservateurs ou « altright » dans le monde anglo-saxon.

Selon Herder, l’homme qui incarne les Lumières allemandes du 18ème siècle, nous devons toujours et partout respecter deux principes, en faire nos fils d’Ariane : « Sapere Aude » (« Ose savoir ! ») et « Gnôthi seauton » (« Connais-toi toi-même »). Il ne peut y avoir de Lumières émancipatrices selon ce pasteur évangélique, venu de Riga en Lettonie actuelle, si l’on ne respecte pas ces deux principes. Si un mouvement politique et/ou philosophique, prétendant dériver des Lumières, n’accepte pas que l’on puisse, sans crainte, oser penser au-delà des lieux communs, qui tiennent le pouvoir et mènent les sociétés vers une dangereuse stagnation, alors les « Lumières » qu’il prétend incarner, ne sont pas de vraies et efficaces « Lumières » mais une panoplie d’instruments pour imposer une tyrannie. Un peuple doit donc se connaître, recourir sans cesse aux sources les plus anciennes de sa culture, pour être vraiment libre. Il n’existe pas de liberté s’il n’y a plus de mémoire. Travailler au réveil d’une mémoire endormie signifie dès lors poser le premier jalon vers la reconquête de la liberté et aussi, finalement, de la capacité à agir de manière libre et utile sur la scène internationale. Herder nous demande donc de retrouver les racines les plus anciennes et les plus vives de notre culture sans manifester une volonté perverse de vouloir les éradiquer.

Un âge d’or ne reviendra dans les sociétés européennes que si -et seulement si- les institutions politiques des « Lumières » fausses et superficielles, dont s’inspirent l’idéologie dominante et la « rectitude politique », seront remplacées par d’autres, inspirées cette fois de nouvelles et puissantes Lumières, telles que Herder les a théorisées. Heidegger ne dira pas autre chose même s’il a utilisé un autre langage, plus philosophique, plus ardu. Pour le philosophe de la Forêt Noire et du Pays Souabe, la civilisation européenne était victime de la « chienlit de la métaphysique occidentale », une chienlit qui devait être éliminée pour qu’une aurore nouvelle puisse se lever. Le vocabulaire utilisé par Heidegger est extrêmement compliqué pour le citoyen lambda. Un professeur américain de philosophie, Matthew B. Crawford, esquisse d’une manière brève et concise l’intention de Heidegger, dont il est l’un des disciples : pour ce Crawford, de la « Virginia University », la « métaphysique occidentale » que fustigeait le philosophe allemand est tout simplement le fatras dérivé des pseudo-Lumières telles qu’elles avaient été formulées par Locke et ses disciples, donc le fatras des pseudo-Lumières françaises et anglaises, parce que celles-ci ne veulent plus avoir aucun contact avec les réalités triviales de notre monde quotidien. Mieux : elles refusent toute approche du concret, posé comme indigne de l’attention du philosophe et de l’honnête homme. Il existe donc, à ce niveau-ci de ma démonstration aujourd’hui, deux courants des Lumières : le courant organique de Herder et le courant abstrait des autres, qui nient la réalité telle qu’elle est et nient aussi le passé réel des peuples.

Crawford revient au concret

Dans cette perspective, Crawford constate que toute société qui persiste à stagner dans un appareil idéologique dérivé de cette interprétation dominante et officielle des Lumières du 18ème, se condamne au déclin et se précipite vers une mort certaine. C’est la raison pour laquelle Crawford a décidé d’abandonner sa chaire et d’ouvrir un atelier de réparation de motos Harley Davidson pour pouvoir humer l’odeur bien réelle du cambouis, de l’essence et du cuir, pour pouvoir écouter la musique des outils heurtant le métal de manière rythmée. Nous avons là une bien singulière option pour un professeur de philosophie cherchant à retourner au concret. Soit. Mais son geste est significatif : en effet, il signifie, sur les plans politique, économique et social, que nous devons rejeter résolument l’« étrangéité au monde » du système actuel dans toutes ses facettes. C’est effectivement cela, et rien que cela, qui constitue notre tâche principale. Cela veut dire qu’il faut se battre pour sauver le concret. C’était aussi l’intention de Heidegger dans tous les aspects de son immense œuvre philosophique.

Cela ne signifie pas pour autant qu’il faille s’enthousiasmer pour un nouveau système totalitaire qu’il conviendrait de promouvoir avec une rage militante, ce qui fut peut-être le fait de Heidegger pendant un moment fiévreux, mais finalement très bref de sa trajectoire. Mais cela signifie à coup sûr une volonté ferme et bien établie de sauver et de défendre la liberté de nos concitoyens et de nos peuples contre un système qui est en train de devenir une véritable camisole de force. Outre Heidegger, qui était resté en Allemagne, il y avait dans le petit monde des philosophes reconnus un autre personnage important pour notre propos : son ancienne étudiante et maîtresse Hannah Arendt qui, dans sa nouvelle patrie américaine, n’a cessé de plaidé pour la liberté contre ce qu’elle appelait la banalité destructrice de nos sociétés libérales d’Occident et des sociétés du monde soviétisé. En effet, après la chute du communisme en Russie et en Europe orientale, les « Lumières » selon Habermas et ses disciples ont été imposées partout sans concurrence aucune, ce qui a eu pour conséquence une réduction absolue des libertés citoyennes dans presque tous les Etats d’Europe occidentale, tout simplement parce que, selon cette idéologie de pure fabrication et dépourvue de toute organicité, rien ne PEUT plus exister qui offrait jadis une épine dorsale à toutes nos sociétés. Au nom d’une notion de liberté qui est purement abstraite, étrangère à tout monde historique concret, les racines des sociétés européennes sont niées et détruites, ce qui achève de ruiner l’équation féconde entre liberté et identité.

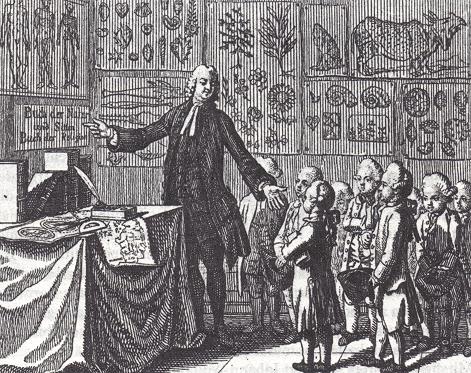

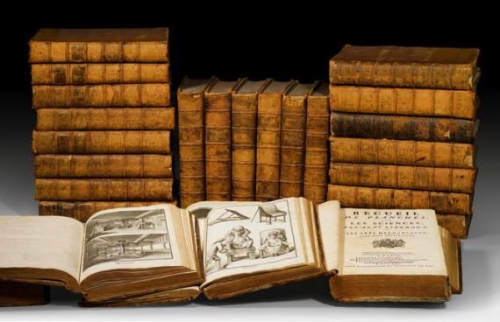

Les Lumières des despotes éclairés

Il me paraît bon de rappeler, ici, qu’il existait au 18ème siècle d’autres Lumières encore, des troisièmes Lumières, en l’occurrence les Lumières des despotes éclairés qui ont modernisé leurs pays ou empires respectifs dans tous les domaines pratiques sans nullement annihiler les valeurs traditionnelles de leurs peuples. Pour les « despotes éclairés » comme Frédéric II de Prusse, Marie-Thérèse ou Joseph II d’Autriche, Catherine II de toutes les Russies ou Charles III d’Espagne, les Lumières sont un dispositif politique, idéologique et culturel permettant la modernisation technique des espaces politiques placés sous leur souveraineté. Il s’agit alors de construire des routes et des canaux, de lancer un urbanisme nouveau, de se doter d’un corps d’ingénieurs compétents au sein de leurs armées, etc. La toute première fonction d’un Etat, dans cette optique, est effectivement de se donner les moyens de procéder à de tels travaux et de maintenir les armées toujours prêtes à mener des opérations en cas d’urgence ou d’Ernstfall, selon l’adage latin, si vis pacem, para bellum.

L’évocation de ces Lumières-là nous ramène à notre époque : tous, dans cette salle, vous êtes bien conscients que la moindre tentative, fût-elle la plus innocente ou la plus inoffensive, de défendre notre identité sera considérée comme un crime par les chiens de garde du monde médiatique, avec, en corollaire, le risque d’être houspillé dans la géhenne des « bruns » ou des « rouges-bruns » ou des « populistes ». Nos contemporains sont toutefois bien moins conscients d’un autre danger mortel : le démantèlement systématique des branches les plus importantes de nos industries, partout en Europe, par le truchement d’un principe particulièrement pervers de l’idéologie néolibérale, celui de la délocalisation. Il faut savoir, en effet, que ce néolibéralisme est l’avatar le plus démentiel des Lumières dominantes, celles qui se placent aujourd’hui dans le sillage de Habermas. Délocaliser, cela signifie justement ruiner l’héritage des despotes éclairés qui ont donné à l’Europe son épine dorsale technique et matérielle. C’est aussi nier et ruiner l’œuvre pragmatique d’un ingénieur et économiste génial du 19ème siècle, Frédéric List (dont les principes de gestion de l’appareil technique, industriel et infrastructurel de tout Etat ne sont plus appliqués que par les Chinois, ce qui explique le formidable succès de Beijing aujourd’hui). De Gaulle, qui avait lu Clausewitz quand il était un jeune officier prisonnier des Allemands à Ingolstadt pendant la première guerre mondiale, était un adepte de ces deux penseurs pragmatiques de Prusse. Il a essayé, dans les années 60 du 20ème siècle, d’appliquer leurs principes de gestion en France. Et c’est justement cette France-là, ou les atouts de cette France-là, que l’on a démantelé petit à petit, selon Zemmour, dès l’accession de Pompidou au pouvoir : la vente, toute récente, de l’entreprise de haute technologie Alstom par Macron à des consortiums américains, allemands ou italiens sanctionne la fin du processus de détricotage industriel de la France. Celle-ci est désormais dépouillée, ne peut plus affirmer qu’elle est véritablement une grande puissance. De Gaulle doit se tourner et se retourner dans sa tombe, dans le petit village de Colombey-les-Deux-Eglises, où il s’était retiré.

Les fausses Lumières qui tiennent aujourd’hui le haut du pavé exigent donc, avec une rage têtue, deux victimes sacrificielles : d’une part, l’identité comme héritage spirituel, qui doit être totalement éradiquée et, d’autre part, la structure économique et industrielle de nos pays, qu’ils soient grandes puissances ou petites entités, qui doit être définitivement détruite. Cette idéologie est donc dangereuse en tous domaines du réel et devrait être effacée de nos horizons le plus vite possible. Et définitivement. Ce que les Américains appellent les « liberal democracies » risquent donc tôt ou tard de périr de la mort lente et peu glorieuse des cancéreux ou des patients atteints de la maladie d’Alzheimer, tandis que les « illiberal democracies » à la Poutine ou à la Orban, ou à la mode polonaise, ou à la façon chinoise et confucéenne finiront par avoir le dessus et par connaître un développement harmonieux sur les plans social et économique. L’amnésie totale et le désarmement total que les Lumières à la Locke exigent de nous, ne nous garantissent qu’un seul sort : celui de crever lentement dans la honte, la pauvreté et la déchéance.

Le remède est donc simple et se résume en un mot magique, « archéofuturisme », naguère inventé par Guillaume Faye. Cela veut dire fédérer les atouts existants, issus des sources mentales de notre humanité européenne, celles que Herder nous demandait d’honorer, issus des idées clausewitziennes quant à l’organisation d’un Etat efficace, issus des principes économiques visant la création d’infrastructures comme le préconisait List.

Crawford, le professeur devenu garagiste, dresse une liste plus exhaustive encore des dangers que recèle les Lumières anglaises de Locke. Cette version des Lumières a induit dans nos mentalités une attitude hostile au réel, hostile aux legs de l’histoire, ce que Heidegger nommera, plus tard, selon Crawford, la « métaphysique occidentale ». Aux yeux de ce philosophe allemand, qui oeuvrait retiré dans son chalet de Todtnauberg, cette métaphysique implique un rejet de toute réalité organique, un rejet de la vie tout court, au profit d’abstractions sèches et infécondes qui conduisent le monde, les sociétés et les Etats, qui ont préalablement cru à un rythme organique et ont graduellement oublié ou refoulé cette saine croyance, à une implosion inéluctable et à une mort assurée.

La question des droits de l’homme

Dans les cercles dits de « nouvelle droite », la critique des « Lumières » dominantes, dans une première étape, a pris la forme d’une critique de la nouvelle idéologie des droits de l’homme, née sous la présidence de Jimmy Carter à partir de 1976 afin de déployer une critique dissolvante du système soviétique, de troubler les relations avec l’URSS, de ruiner les ressorts de la « coexistence pacifique » et de torpiller la bonne organisation des Jeux Olympiques de Moscou. La nouvelle diplomatie des droits de l’homme, qui a émergé suite à ce discours, a été considérée, à juste titre, comme un déni de la diplomatie classique et de la Realpolitik de Kissinger. Pour promouvoir cette nouvelle idéologie dans les relations internationales, une véritable offensive métapolitique a eu lieu avec mobilisation de toutes les ressources du soft power américain, très expérimenté en ce domaine. Dans les officines des services secrets, on a alors forgé des instruments nouveaux, adaptés à chaque contexte national : en France, et pour l’environnement francophone, l’instrument s’est appelé la « nouvelle philosophie », avec des figures de proue comme Bernard-Henri Lévy et André Glucksmann. A partir de la fin des années 70, les idées grossièrement bricolées de Lévy ont toujours correspondu aux objectifs géopolitiques des Etats-Unis, jusqu’à la mort atroce du Colonel Khadafi en Libye, jusqu’au soutien qu’il apporte aujourd’hui aux Kurdes en Syrie et en Irak.

Face à ce formidable appareil relevant du soft power, la « nouvelle droite » avait peu de chance d’être réellement entendue. Et les arguments de ses porte-paroles, bien que justes en règle générale, étaient assez faibles sur le plan philosophique, presque aussi faibles, dirais-je aujourd’hui, que ceux de Lévy lui-même. La situation s’est modifiée depuis quelques années : l’idéologie bricolée des droits de l’homme et de la nouvelle diplomatie (au niveau international), qui en est un corollaire, ont conduit à une longue série de catastrophes belligènes et sanglantes. Elles sont soumises désormais à une critique pointue, au départ de tous les cénacles idéologiques. Deux professeurs de Bruxelles, issus pourtant de l’ULB, très à gauche, Justine Lacroix et Jean-Yves Pranchère, ont eu le mérite de rouvrir et de résumer le vieux dossier des droits de l’homme. L’idéologie des droits de l’homme a toujours été utilisée pour détruire et les institutions héritées du passé et les droits et libertés concrets, comme l’avait d’ailleurs constaté Burke immédiatement après leur proclamation au début de la révolution française. Burke était certes une figure du conservatisme britannique. Mais, plus tard, cette idéologie a également été critiquée par des figures du camp des gauches ou du camp libéral. Jeremy Bentham et Auguste Comte la considéraient comme un obstacle à l’« utilité sociale ». Marx estimait qu’elle était le noyau de l’idéologie bourgeoise et constituait donc un obstacle, cette fois contre l’émancipation des masses. Aujourd’hui, cependant, nous pourrions parfaitement critiquer cette idéologie des droits de l’homme en disant qu’elle est à la fois l’instrument efficace d’une grande puissance extérieure à l’Europe et l’instrument d’une subversion généralisée qui entend détruire aussi bien les institutions héritées du passé que les droits traditionnels des peuples. Pourtant, force est de constater que cette idéologie n’a plus aucune utilité sociale car, en tablant sur elle et sur ses éventuelles ressources, on ne peut plus résoudre aucun problème majeur de nos sociétés ; bien au contraire, en la conservant comme idole intangible, on ne cesse de créer et d’accumuler problèmes anciens et nouveaux. Devant ce constat, toutes les critiques formulées jadis et maintenant à l’encontre des dits « droits de l’homme » s’avèrent utiles pour former un vaste front contre les pesanteurs écrasantes du « politiquement correct ». La première étape, dans la formation de ce front, étant la volonté de remettre le droit (les droits), les sociétés et les économies dans leur cadres naturels, organiques et historiques, de les re-contextualiser.

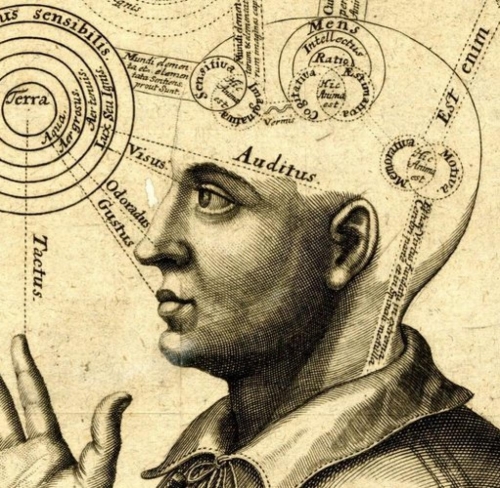

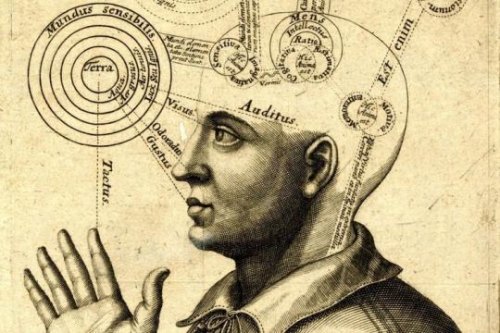

Résultat : un déficit récurrent d’attention

Pour Crawford, les Lumières dominantes et tous leurs avatars, dans ce qu’ils ont d’éminemment subversif, surtout dans la version « lockienne » qu’il critique tout particulièrement, conduisent à toutes les pathologies sociales et politiques que nous observons aujourd’hui, surtout dans le chef des enfants et des adolescents, notamment la perte de « cette antique capacité à être toujours attentifs à tout », ce que certains pédagogues allemands actuels, comme Christian Türcke (photo), appellent l’ « Aufmerksamkeitsdefizitkultur » (la « culture du déficit d’attention »). Nos jeunes contemporains sont donc les dernières victimes d’un long processus qui a connu ses débuts il y a deux ou trois siècles. Mais nous assistons aussi à la fin de ce processus subversif et « involutif » qui nous a menés à un « Kali Youga ». La mythologie indienne nous enseigne bel et bien qu’après ce « Kali Youga », un nouvel âge d’or commencera.

Pour Crawford, les Lumières dominantes et tous leurs avatars, dans ce qu’ils ont d’éminemment subversif, surtout dans la version « lockienne » qu’il critique tout particulièrement, conduisent à toutes les pathologies sociales et politiques que nous observons aujourd’hui, surtout dans le chef des enfants et des adolescents, notamment la perte de « cette antique capacité à être toujours attentifs à tout », ce que certains pédagogues allemands actuels, comme Christian Türcke (photo), appellent l’ « Aufmerksamkeitsdefizitkultur » (la « culture du déficit d’attention »). Nos jeunes contemporains sont donc les dernières victimes d’un long processus qui a connu ses débuts il y a deux ou trois siècles. Mais nous assistons aussi à la fin de ce processus subversif et « involutif » qui nous a menés à un « Kali Youga ». La mythologie indienne nous enseigne bel et bien qu’après ce « Kali Youga », un nouvel âge d’or commencera.

Dans les temps très sombres qui précèderont ce nouvel âge d’or, donc dans les temps que nous vivons maintenant, la première tâche de ceux qui, comme nous, sont conscients de notre déchéance, est de redevenir « hyper-attentifs » et de le rester. Si les Lumières anglo-saxonnes introduites jadis par Locke, si ce que Heidegger appelait la « métaphysique occidentale » nous décrivent le monde concret comme une malédiction qui ne mérite pas l’attention du philosophe ou de l’intellectuel, si cette version-là des Lumières voit la réalité comme un fatras misérable de choses sans valeur aucune, si l’idéologie des « droits de l’homme » considère que l’histoire et les réalisations de nos ancêtres sont dépourvues de valeur ou sont mêmes « criminelles », les Lumières, telles qu’elles ont été envisagées par Herder, bien au contraire, veulent l’inverse diamétral de cette posture. Les Lumières populaires, folcistes et organiques de Herder veulent justement promouvoir une attention constante à l’endroit des racines et des sources, de l’histoire, de la littérature et des traditions de nos peuples. Les véritables objectifs politiques et stratégiques, qu’ont déployé les « despotes éclairés » et les adeptes des théories pratiques de Friedrich List dans leurs Etats respectifs, exigent de tous responsables politiques une attention constante aux réalités physiques des pays qu’ils organisent, afin d’en exploiter les ressources naturelles ou afin de les façonner (« gestalten ») de manière telle qu’elles deviennent utiles aux peuples qui vivent sur leurs territoires. Revenir à un âge d’or signifie donc rejeter résolument toutes les idéologies qui ont détruit les « capacités d’attention » des générations successives jusqu’à la catastrophe anthropologique que nous vivons actuellement.

Kairos

Si la volonté de concentrer à nouveau toutes les attentions sur la concrétude, qui nous entoure et nous englobe, sera un processus de longue durée, sortir de l’impasse et ré-inaugurer un éventuel âge d’or nécessite de saisir le moment kaïrologique, le moment du petit dieu Kairos. De quoi s’agit-il ? Kairos est le dieu grec des temps forts, des moments exceptionnels, tandis que Chronos est le dieu du temps banal, du temps que l’on peut mesurer, de la chronologie pesante et sans relief, de ce que Heidegger nommait la « quotidienneté » (l’Alltäglichkeit). L’écrivain néerlandaise Joke Hermsen a publié un livre capital sur Kairos et le temps kaïrologique, il y a trois ans. Le temps fort, que symbolisme le mythe de Kairos, est, politiquement parlant, le temps de la décision (Entscheidung) chez Heidegger, Jünger et Schmitt, le temps où, subitement, des hommes décidés osent l’histoire. Kairos est donc le dieu du « bon moment », lorsque des figures charismatiques, des éveilleurs de peuple (Mabire) chanceux se saisissent soudainement du destin (Schicksal). Les Grecs de l’antiquité représentaient Kairos comme un dieu jeune, la tête surmontée d’une petite touffe de cheveux au niveau du front. Le dompteur du destin est celui qui parvient à se saisir de cette touffe, tâche difficile que peu réussissent. Se saisir du destin, ou des cheveux de Kairos, n’est pas une tâche que l’on parachève en calculant posément, en planifiant minutieusement, trop lentement, mais quand elle s’accomplit, avec une flamboyante soudaineté, naissent des temps nouveaux, un nouvel âge d’or peut commencer. Car, de fait, amorcer de nouveaux commencements (Anfänge) est bien le destin des hommes authentiques selon Heidegger et Arendt.

Peut-être qu’en cette salle se trouve quelqu’un qui, un jour, saisira les cheveux de Kairos. C’est ce que j’ai voulu expliquer, ici, aujourd’hui.

Je vous remercie pour votre attention.

19:03 Publié dans Nouvelle Droite, Révolution conservatrice, Synergies européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : rotterdam, événement, erkenbrand, pays-bas, robert steuckers, âge d'or, nouvelle droite, synergies européennes, révolution conservatrice, lumières, aufklärung, idéologie des lumières |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 08 février 2016

Door de Verlichting verblind

Door de Verlichting verblind

Kan het liberalisme de islamisering nog stuiten?

Door Marcel Bas

"Een ander uitstekend middel is het zenden van kolonisten naar een of twee

plaatsen; de aldaar gestichte koloniën zijn als het ware de sleutels van de

nieuwe staat. Deze maatregel is noodzakelijk; anders toch moet men in het

nieuw veroverde land veel troepen op de been houden. Het stichten van

nederzettingen kost de vorst niet veel (...)"

– Niccolò Machiavelli, De Vorst, 1532

"Car il n'est pas intellectuellement élégant, intellectuellement chic d'admettre

que le fondement d'une civilisation est ethnique. J'évoquerai plus loin l'utopie de

cette vision communautariste ou intégrationniste de l'Europe, en défendant le

principe de l'unité ethnique et de l'ethnocentrisme contre l'ethnopluralisme. (...)

Le courage idéologique consiste aujourd'hui à défendre l'ethnocentrisme."

– Guillaume Faye, La Colonisation de l'Europe, 2000

"Das Volk hat das Vertrauen der Regierung verscherzt. Wäre es da nicht

doch einfacher, die Regierung löste das Volk auf und wählte ein anderes?"

– Bertolt Brecht, 1953

De aanhoudende groei van het aantal moslims in Noord- en West-Europa leidt tot de vrees dat de islam er een steeds grotere invloed zal verwerven. Onze Westerse, uit de Verlichting voortgekomen verworvenheden – variërend van homorechten tot de vrijheid van meningsuiting – zouden namelijk op gespannen voet staan met de islamitische leefregels. Politici en filosofen trachten die vrees te bezweren door de verlichtingswaarden als universele waarden te presenteren en te pleiten voor nog sterkere omarming ervan. Tegelijkertijd wordt christelijke Oost-Europese landen, die niets van massa-immigratie willen weten, door politici verweten "xenofoob" te zijn, en "nog niet multi-etnisch" te denken. Maar zijn onze verlichtingswaarden wel zo universeel? En in hoeverre zullen die nog in staat zijn ons voor verdere islamisering te behoeden? En kunnen wij juist niet veel leren van de Oost-Europeanen als het aankomt op het behoud van onze Europese beschaving?

De huidige politieke reactie

De massale toestroom van moslims in de afgelopen decennia, en vooral in 2015 en 2016, heeft in Noord- en West-Europa geleid tot de vestiging en groei van een islamitische zuil. Hier en daar doen zich hachelijke situaties voor, waar politici op hebben moeten reageren. Zo zijn er salafistische terreuraanslagen gepleegd, is er becijferd dat moslimmannen in Zweden zich tientallen malen meer aan Zweedse vrouwen vergrijpen dan Zweedse mannen dat doen, en blijkt dat in de Engelse stad Rotherham een moslimbende 1.400 overwegend autochtone meisjes heeft misbruikt, verkracht en vermoord.

Tijdens de beruchte jaarwisseling van 2015–2016 hadden moslimaanranders en -verkrachters het niet alleen in het Duitse Keulen, maar ook elders in Noord- en West-Europa op inheemse vrouwen gemunt. Het bleek dat zulke aberraties eigenlijk al jaren schering en inslag waren tijdens feestelijkheden in Duitsland en Scandinavië, waarbij vrouwen op grote schaal door moslims aangerand en verkracht werden.

" De Duitse en Zweedse overheden en media waren erin geslaagd deze feiten jarenlang onder de pet te houden. Pas nadat de wal het schip gekeerd had, gaven zij schoorvoetend toe dat zij er geen ruchtbaarheid aan wilden geven, uit angst om de daders te zeer als collectief voor te stellen en zo van discriminerend gedrag beticht te worden."

De Duitse en Zweedse overheden en media waren erin geslaagd deze feiten jarenlang onder de pet te houden. Pas nadat de wal het schip gekeerd had, gaven zij schoorvoetend toe dat zij er geen ruchtbaarheid aan wilden geven, uit angst om de daders te zeer als collectief voor te stellen en zo van discriminerend gedrag beticht te worden.

Niet alleen onze vrouwen worden belaagd: ook homo’s en joden worden door moslims uitgejouwd en belasterd. Hiertegenover stellen Noord- en West-Europese bewindslieden, zoals minister-president Mark Rutte (maar ook de meest conservatieve politici), dat er aan onze aan de Verlichting ontsproten waarden en verworvenheden niet getornd wordt. Rutte c.s. hebben meerdere malen verklaard dat die waarden de vrijheid garanderen waarmee vrouwen, homo's en joden zich op straat mogen vertonen. Wie die niet respecteert, hoort hier niet thuis. Eenieder kan zich de Verlichting eigen maken: in reactie op 'Keulen' verklaarde de Amerikaanse filosofe Susan Neiman dan ook hoopvol dat de Verlichting niet is beperkt tot één cultuur, maar dat het een universele beweging is die in Europa gewoon beter is gerealiseerd dan elders.

Voorvallen zoals in Keulen genereren veel media-aandacht. Die kunnen rekenen op kordate reacties van politici en meningsvormers. Er zijn echter kwesties die veel dieper en langduriger op onze cultuur zullen ingrijpen. Neem nu de strijd om groepsbelangen. Reeds nu krijgen wij te maken met islamitische eisen zoals het recht voor vrouwen – ongeacht hun functie – om overal islamitische doeken en versluieringen te dragen. En wat te denken van het verbannen van kerstbomen of andere christelijke symbolen uit openbare instellingen, het inruilen van christelijke feestdagen voor islamitische feestdagen, het recht om moskeeën en islamitische scholen te bouwen, het recht op halalvoedsel, het recht op gezinshereniging na gezinshereniging? Deze belangenstrijd zal de komende decennia in intensiteit toenemen en zal onze landen ingrijpend veranderen. Tenzij ook deze problematiek op een krachtig politiek-filosofisch weerwoord kan rekenen. Doch dat blijft uit.

Verlichting en liberalisme

Rutte c.s. noemen de Verlichting; uit deze filosofische stroming kwam het liberalisme voort. Het liberalisme is de politiek-maatschappelijke invulling van de Verlichting. Vooral na de ineenstorting van het fascisme en het communisme is het neoliberalisme in onze landen heersend. In Nederland en de oudere EU-lidstaten verkondigen bijna alle politieke partijen het liberale verhaal. Als een politicus of het Verdrag van Lissabon (artikel 1) Europese waarden verkondigen, dan worden daarmee de verlichtingswaarden van het neoliberalisme bedoeld.

Vrijheid, Gelijkheid en Broederschap

In de negentiende eeuw verbreidde het verlichte liberalisme zich door West-Europa onder de leuze Vrijheid, Gelijkheid en Broederschap: het gaat uit van de soevereiniteit van het individu en de rede. Het individu heeft de vrijheid te kiezen hoe hij zijn leven leidt: hij kan ervoor kiezen tot wel of geen gemeenschap te behoren, wel of geen religie aan te hangen, zijn identiteit aan zijn volksgenoten of aan het kopen van consumptiewaar te ontlenen, enzovoorts. De ooit onwrikbare drie G's – Gezin, Gemeenschap en Geloof – zijn vervolgens onderhandelbaar en relatief geworden. Collectieven zouden maar tot onderhorigheid en tweespalt leiden, maar eenmaal opgedeeld in individuen zal men ervoor kunnen kiezen zich gebroederlijk en rationeel gedragen, en een betere wereld te creëren.

"De Verlichting herdefinieert en deelt van alles op; het huwelijk en de kleinste natuurlijke gemeenschap, het gezin, incluis."

De Verlichting herdefinieert en deelt van alles op; het huwelijk en de kleinste natuurlijke gemeenschap, het gezin, incluis. Deze instituties zouden niet langer deel uitmaken van Gods orde. Niet langer is het huwelijk voorbehouden aan man en vrouw, of is het gezin het vanzelfsprekende nestje waarin kinderen geboren en opgevoed worden. De regulering en het causaal verband tussen seks en voortplanting zijn dan ook kwesties van eigen, individuele keuzen geworden. Dit is onlangs geculmineerd in het liberale verschijnsel waarbij paren van het gelijke geslacht ook mogen huwen. Zulke paren mogen zelfs kinderen hebben – al heeft de Voorzienigheid eigenlijk bepaald dat dit helemaal niet kan.

Dit heeft ertoe geleid dat de vanzelfsprekende, organische aanvullendheid van man en vrouw betwijfeld wordt. Aangestuwd door LGTB-bewegingen heeft men nu in Zweden in officiële documenten het 'derde geslacht' geïntroduceerd, en zijn in Frankrijk de begrippen vader en moeder heel pragmatisch gewijzigd zijn in ouder 1 en ouder 2. Fysiek gezien zijn personen niet op te delen, maar volgens de Verlichting kan hun identiteit dus wel bijgesteld en geherdefinieerd worden. Er zijn nu, logischerwijze, individuen beschreven die met een boom willen huwen, of die beweren dat ze "in het verkeerde lichaam zitten" en eigenlijk een kat zijn. Vervolgens bekeren steeds meer onzekere Europese vrouwen zich tot de islam, waar ze de in het Westen gemiste geborgenheid en richtlijnen van de drie G's wél aantreffen.

Dit soort existentiële dissociatie maakt deel uit van de voortgaande individualisering van de maatschappij: het stokpaardje van het liberalisme.

Individualisme gaat ook hand in hand met de gedachte dat het ene collectief gelijk is aan het andere. De Nederlandse liberale Grondwet van 1848 was opgesteld om de godsdienststrijd tussen protestanten en katholieken te sussen. In de geest van die Grondwet is de ene religie niet meer waard dan de andere. Het maakt niet uit of de ene religie hier verworteld is en de andere niet. Er is dus bepaald dat er niet alleen vrijheid van religie is, maar ook gelijkheid van religies. Thans mag elke religie in Nederland haar eigen gebedshuizen en onderwijsinstellingen oprichten.

Thans mag elke religie in Nederland haar eigen gebedshuizen en onderwijsinstellingen oprichten.

Christelijke gezindten zijn gelijk aan elkaar, maar sinds de massa-immigratie is de islam dat nu ook aan het hier gegroeide en verwortelde christendom.

Etnische collectieven zijn volgens het liberalisme ook gelijk aan elkaar. De ene etnische groep beschikt immers niet over meer rechten ergens te wonen dan de andere. Anders zouden we discrimineren. Het enige dat boven alle twijfel verheven zou moeten zijn, is de liberale rechtsstaat met zijn vrijheden en parlementaire democratie. Mensen die het daar niet mee eens zijn, zijn niet vrij daarvoor uit te komen. Met name Westerse landen doen er veel aan de verworvenheden van de Verlichting te exporteren naar Centraal- en Oost-Europa, en naar moslimlanden.

Waarden en normen zijn volgens het liberalisme relatief en lokaal, behalve als zij zijn voortgekomen uit de kernwaarden van de Verlichting. Dan zijn zij ononderhandelbaar en universeel.

De nieuwe werkelijkheid

Nu hebben we te maken met aanhoudende massa-immigratie vanuit moslimlanden en een voortdurende aanwas van nieuwe generaties moslims in onze landen. En men vraagt zich af of de verworvenheden van de Verlichting nu onder druk staan. De vraag die ik echter zou willen stellen is: kunnen we met de kernwaarden van de Verlichting in de hand hier nog wel een dam opwerpen tegen de islam?

De volkeren van het Midden-Oosten

Laat ons daarvoor eerst bepalen met wie wij te maken hebben.

"Volkeren in het Midden-Oosten denken van nature collectivistisch en etnocentrisch. "

Volkeren in het Midden-Oosten denken van nature collectivistisch en etnocentrisch. Hun pastorale voorouders groepeerden zich in grote herdersfamilies en op evolutionair beslissende momenten moesten dit soort sibbegemeenschappen (clans) met elkaar concurreren. Zij werden patriarchaal geleid, d.w.z. (familie)leden waren gehoorzaam aan een mannelijke stamhouder, en de groep betrachtte een strijdvaardige houding tot andere groepen. Men bewaakte een duidelijke afbakening van de ingroup tegenover de outgroup.

Uitbreiding van de zo belangrijke, tot loyaliteit nopende onderlinge verwantschap, bijvoorbeeld door endogamie, uithuwelijking, polygynie en het verwekken van veel kinderen, vergrootte de invloed van de groep op de leefomgeving. Binnen de groep was er weinig ruimte voor individualisme en buiten de groep was er weinig ruimte voor altruïsme want collectieven waren niet gelijk aan elkaar. En iets was moreel juist zolang de groep ervan profiteerde.

De volkeren van Noord- en West-Europa

In het geval van zware beproevingen neigen ook wij tot tribalisme. Wij zijn dus wel collectivistisch aangelegd, maar kwalitatief minder dan de volkeren uit het Midden-Oosten. Onze voorouders zouden gedurende de laatste IJstijd een evolutionair belangrijke periode hebben doorgemaakt. Zij waren toen jagers-verzamelaars die zich vanwege het ruige klimaat groepeerden in vaak geïsoleerde, relatief kleine families waarbij de man de taak tot levensmiddelenverschaffer op zich nam. Isolement, kou en schaarste noopten tot monogamie, onderlinge affectie en relatieve gelijkheid tussen de seksen. Het aanhalen en versterken van bredere familiebanden leverden in onze wordingsgeschiedenis geen significante voordelen op, dus het zoeken van een partner gebeurde buiten de eigen verwanten (exogamie). Hierdoor was er ruimte voor meer individualisme en werd de groep nog minder gekenmerkt door sterk patriarchale verhoudingen.

" Dit verloop heeft de Noord- en West-Europese volkeren in zekere zin een goedmoedige, niet-etnocentrische, ontvankelijke doch individualistische inborst gegeven. "

Het contrast tussen ingroup en outgrouphoefde niet groot te zijn. Moraal was en is onder onze volkeren universeel: iets is moreel juist, ongeacht de vraag of het de groep ten goede komt. Vervolgens verleende het christendom ons het geloof in gelijkheid voor God, onder christenen. Dat raakte echter seculier en veralgemeniseerd tot de idee dat alle mensen, waar dan ook, aan elkaar gelijk zijn.

Dit verloop heeft de Noord- en West-Europese volkeren in zekere zin een goedmoedige, niet-etnocentrische, ontvankelijke doch individualistische inborst gegeven. Het maakt aannemelijk dat de Verlichting hier in Noord- en West-Europa zo heeft kunnen aanslaan omdat wij over een primordiale geneigdheid tot openheid en individualisme beschikken.

We denken en hopen dat onze kernwaarden universeel zijn, en we gunnen de nieuwkomer dezelfde zegeningen. Maar die waarden zijn niet universeel. Het op zich heel legitieme en functionele waardenstelsel van de islam is daar een van de vele bewijzen voor.

Liberale uitholling van het volksbegrip

Een liberale overheid waakt over burgers, ongeacht of die wel of geen volk ofummah (de moslimgemeenschap) vormen. In onze samenleving is het etnische begrip volk steeds verder op de achtergrond geraakt en misschien zelfs lastig geworden, aangezien het Nederlands staatsburgerschap door de massa-immigratie steeds minder een zaak van het Nederlandse volk is geworden. Een volk vormt een eenheid op grond van onderlinge verwantschap en een gedeelde geschiedenis. Staatsburgerschap, daarentegen, kan hoofdzakelijk gebaseerd zijn op territorialiteit en nationaliteit: het is het gevolg van rationele en juridische overeenkomsten met de staat waarvoor eenieder kan kiezen die te onderschrijven of na te leven. Staatsburgerschap is dus, in beginsel, een open systeem. Volkswezen, daarentegen, vindt zijn oorsprong in de biologische, niet-rationele, collectivistische sfeer. Daar valt weinig in te kiezen. Het is, als het ware, aangeboren. Onder invloed van de rationele verlichtingskernwaarden is volkswezen dan ook omstreden geraakt.

Begrippen als volk en volkswezen "sluiten mensen uit", zoals dat tegenwoordig heet. Autochtonen die uit zelfbehoud een beroep doen op het collectivistische volksbegrip en die vervolgens, uit een gevoel van verbondenheid, het opnemen voor hun eigen mensen, zouden wel eens van discriminatie – een strafbare schending van artikel 1 van de Nederlandse Grondwet – kunnen worden beticht. Discriminatie is in het liberale Westen een nieuwe zonde. Ondertussen dendert het proces waarin autochtonen toenemend uit hun natuurlijke gemeenschappen losgeweekt raken, onverminderd voort, terwijl allochtonengemeenschappen groeien en zich collectief steeds effectiever organiseren.

In hun pogingen op te komen voor de belangen van de eigen groep in een door Westerlingen overheerste omgeving, organiseren moslims zich ongestoord langs etnisch-religieuze lijnen. Getuige de inmiddels vele onderscheidenlijk Turkse en Marokkaanse moskeeën en belangenorganisaties is de 'in ballingschap' verkerende ummah minder internationalistisch en veel etnocentrischer dan door Mohammed beoogd was. Er is niet veel wat ons op individualisme en vrije keuzen geënte bestel daartegen kan inbrengen. Behalve dan nog meer te hameren op verlichtingswaarden en autochtoon etnocentrisme af te straffen.

" Onze liberale Grondwet kwam tot stand in een autochtoon, christelijk Nederland. Maar nu draagt deze exponent van de Verlichting aan de ene kant bij tot verdere versterking van de islam in ons land, en aan de andere kant tot verzwakking van onze autochtone identiteit. "

Onze liberale Grondwet kwam tot stand in een autochtoon, christelijk Nederland. Maar nu draagt deze exponent van de Verlichting aan de ene kant bij tot verdere versterking van de islam in ons land, en aan de andere kant tot verzwakking van onze autochtone identiteit. Onze overheid is grondwettelijk gezien namelijk genoodzaakt het behoud van de islam te faciliteren door de bouw of oprichting van de moskeeën en islamitische scholen te ondersteunen.

Daarnaast voorziet de Grondwet in representatieve democratie. Ook deze is ooit in het leven geroepen onder de invloed van de Verlichting. Dit was haalbaar binnen die oude, autochtone, christelijke Nederlandse natie. Nederland was al geruime tijd een natiestaat; men deelde dezelfde waarden, christelijke ethiek, geschiedenis en etniciteit. Het electoraat vormde, kortom, een volk. Daarop kon het liberalisme gedijen, terwijl het de oude christelijk-sociale initiatieven en hiërarchieën afbrak. Maar hoe meer islamieten het Nederlands staatsburgerschap kunnen verwerven, hoe minder ons volk zich in zijn natiestaat zal kunnen herkennen. Ook democratie is inmiddels steeds minder een kwestie van het volk geworden. Bij voortduring kan dit proces ontaarden in een strijd om behartiging van tegengestelde, etnische belangen. Hier moeten wij op voorbereid zijn. Autochtonen zijn zich echter nog niet erg bewust van hun eigen etnische belangen. Allochtone minderheden, en inzonderheid moslims, zijn zich dat wel.

Paradoxen

Er voltrekt zich aldus een proces waar etnische minderheden onevenredig veel invloed verwerven in de Nederlandse en Westerse politiek en samenleving. De islamitische gemeenschap is groot, doch de inheemse Nederlanders zijn demografisch nog veruit in de meerderheid. Maar als die meerderheid zich de inschikkelijke rol van een minderheid aanmeet, bijvoorbeeld uit angst om te discrimineren of om haar individualistische kernwaarden te verloochenen, dan kent zij haar eigen collectieve belangen niet.

"Autochtonen zijn zich echter nog niet erg bewust van hun eigen etnische belangen. Allochtonen, en inzonderheid moslims, zijn zich dat wel. "

Tot nu toe schamen wij, niet de moslims, ons voor dit soort 'primitieve' belangen. Haast altruïstisch accepteren wij tijdens verkiezingen etnisch stemgedrag onder moslims, geven we kinderbijslag aan grote moslimgezinnen en willen we aanranders in Keulen niet collectief stigmatiseren.

Migranten uit de Oriënt beschouwen zich echter weldegelijk als een collectief. Juist in onze landen, dus eenmaal buiten de islamitische landen woonachtig, neigen zij als minderheid sterker naar de eigen ummahen/of de eigen etnische groep.

Hun religieus en etnocentrisch collectivisme, versterkt door primordiaal wantrouwen jegens de andere groep, druist juist in tegen de door onze politici gepropageerde liberale kernwaarden en verworvenheden van de Verlichting. De islam en de daaraan verbonden mentaliteit zijn ons dan ook wezensvreemd. De islam weerspiegelt de orde die binnen de sibbegemeenschap heerst: de overheid, het recht, het huwelijk, de verhoudingen tussen man en vrouw, het individu en de sibbegemeenschap zelf zijn er ondergeschikt aan Allah. In het Westen is echter alles, ook onze religie, onder invloed van de Verlichting ondergeschikt geraakt aan de door onszelf ingestelde overheid, die allen als gelijken dient te behandelen, maar die zelf, door het democratisch proces, ook onderhevig is aan verandering en bijstelling van onderaf.

De paradox is nu dat 'onverlichte' waarden en overlevingsstrategieën van minderheden alhier kunnen gedijen dankzij de kernwaarden van de Verlichting. De paradox wordt groter als we zien dat het nut van deze waarden sterk tot voordeel van moslims strekt. Nóg groter is de paradox als we zien dat Noord- en West-Europeanen als reactie op de islamitische nieuwkomers tegenwoordig geneigd zijn die waarden te overdrijven. Een voorbeeld: in antwoord op islamitische homokritiek beschouwen wij het als iets typisch Nederlands om massaal op te komen voor homorechten zoals het zgn. homohuwelijk. Het ontgaat ons echter dat wij daarmee afbreuk doen aan het huwelijk als een door God gegeven verbintenis tussen man en vrouw, en als plek waar de toekomstige generaties van ons volk geboren zullen worden. Dit klimaat van autochtone ontwaarding van het huwelijk en het loskoppelen van seks en voortplanting hebben het aantal autochtone echtscheidingen ernstig doen stijgen en het aantal autochtone geboorten dramatisch doen dalen.

Maar hoezeer wij tegenwoordig ook beginnen te geloven dat de Verlichting ons ten overstaan van de islam een identiteit kan verschaffen, heeft diezelfde Verlichting ons geleerd dat het ene collectief niet beter is dan het andere. Men mag niet aan de fundamenten van de liberale rechtsstaat zagen, maar als wij afgeleerd hebben de ene cultuur als waardevoller in te schatten dan de andere, dan is er niet veel rationeels in te brengen tegen iets als het multiculturalisme of islamitische kritiek op de typisch Westerse Verlichting. Als onze cultuur niet geschikter of beter is om hier leidend te zijn, wie zijn wij dan om de toevloed van alloculturele migranten tegen te gaan? Wij moeten onze medemensen uit het Midden-Oosten en de Maghreb gewoon als individuen verwelkomen, de grenzen openzetten, en hun culturen hier naast de onze laten floreren.

Liberalisme schaft zichzelf af

Zulk cultuurrelativisme is een gevaarlijke gedachtegang. Wat ons onderscheidt van nieuwkomers is onze gemeenschappelijke herkomst, die wij als Europeanen, Nederlanders, delen. Die gemeenschappelijkheid zou ons ertoe in staat kunnen stellen onze eigenheid t.a.v. de islam te bewaren, en de aanvaardbaarheid van de islamitische identiteit hier te lande tegen te gaan. In onze reactie op de islam verdedigen wij nu echter nog edelmoedig de waarden van de Verlichting en het liberalisme als een oplossing.

Pegida, voluit Patriotische Europäer gegen die Islamisierung des Abendlandes, is een van de vele Duitse massabewegingen tegen het cultuurrelativisme

Het probleem met het liberalisme is dat het eindig is. Deze politiek-maatschappelijke invulling van de Verlichting slaagt er vooral in burgerschap en individualisme te propageren onder mensen die zich nog bewust zijn van hun collectieve belangen en wederkerigheid als volk, als christenen, als gezinnen, e.d. Maar na individualisering van de massa zal het liberalisme niet proberen dit oude collectivisme nieuw leven in te blazen.

Eenmaal consequent doorgevoerd, heft het verlichtingsproject van het liberalisme zichzelf op, omdat het alles opdeelt en gelijktrekt. Zichzelf incluis. Immers, de verlichte politieke praktijk kan enkel tot haar recht komen zolang de bevolkingsgroepen er belang bij hebben elkaar vanuit oude collectivistische structuren en identiteiten met wederzijds respect en wederzijdse afhankelijkheid tegemoet te treden. Die structuren en identiteiten zijn echter in wezen pre- of onliberaal, en derhalve problematisch en genomineerd om ontbonden te worden, aangezien zij 's mensen keuzevrijheid beperken.

Uiteindelijk heeft dit tot gevolg dat de collectivistische levenssappen waarmee het liberalisme zichzelf als 'neutraal' alternatief voor partijdig collectivisme heeft kunnen voeden, onder de individualiserende en centraliserende invloed van datzelfde liberalisme opgedroogd zullen raken.

"(...) ook het bij uitstek nominalistische liberalisme als beschavingsverschijnsel zal zelf geen verbanden met de realiteit meer blijken te hebben. "

Besef van de verbanden tussen individu, gezin, familie, gemeenschap, volk, natuur, cultuur, beschaving, gezag, geweten en metafysica zal geërodeerd zijn, en ook het bij uitstek nominalistische liberalisme als beschavingsverschijnsel zal zelf geen verbanden met de realiteit meer blijken te hebben. De geschiedenis van het liberalisme is het verhaal van afbraak van natuurlijke en lokale gemeenschappen, waarvan de vrijgekomen autoriteit en middelen gecentraliseerd en overgeheveld worden naar de staat of naar nog grotere bestuurslichamen zoals de Europese Unie. Individualisme raakt doorgeschoten. Dat houdt in dat de van hun sociaal-culturele netwerken 'bevrijde' individuen steeds afhankelijker van hun overheden raken en dat de staat en de supranationale verbanden (de EU) steeds machtiger worden.

Gesteld tegenover collectivistisch aangelegde, etnocentrische moslimgemeenschappen zal het liberalisme ons dus erg verzwakken. Waarschijnlijk komt er een tijd waarin de optimistische bevrijdingsboodschap van het liberalisme – nog steeds parasiterend op restanten van het geseculariseerde christendom – het individu enkel nog zou kunnen aanzetten tot ongeloof in alles, behalve in het eigen gelijk, in het recht op individueel genot, zolang de Staat maar zijn werk kan doen. Als de liberale agenda is volbracht, is er niets meer voor het individu van waaruit hij de 'vrijheid' tegemoet kan gaan. Het zal vooral de autochtone, door de Verlichting verblinde ik-mens verzwakken, en de allochtone wij-denker binnen zijn collectief versterken. Het is dan ook verstandig dat ook wij ons nu reeds meer collectief organiseren, om goed voorbereid te zijn op komende tijden van chaos. In tijden van crisis hebben we elkaar als collectief weer nodig.

In het licht van de door migratiestromen aangezette omvorming van Noord- en West-Europa heeft de verlichte, Duitse Willkommenskultur tegennatuurlijke trekken gekregen

De processen die we thans in Noord- en West-Europa zich zien voltrekken nopen ons ertoe het nut van de verworvenheden van de Verlichting opnieuw tegen het licht te houden. Nu het Avondland zo ingrijpend en mogelijk blijvend veranderd is, is de Verlichting nauwelijks nog een oplossing te noemen. De Verlichting is een deel van het probleem geworden. Doch zolang de versluierd aanwezige, oude, collectivistische structuren van de oorspronkelijke Europese bevolking nog aanwezig zijn, is er hoop. We moeten terug naar dit wij, en niet naar meer ik. Het gevoel van volkseenheid, de christelijke beschaving en de neiging je gemeenschappelijk te verzetten tegen migratie zijn voorbeelden van dit oude wij. En die treffen we nog volop aan in Oost-Europa. Voor een oplossing van ons probleem zouden wij daar te rade kunnen gaan.

Balkanisering

Noord- en West-Europa ondergaan momenteel een proces van balkanisering – laat ons toch het beestje bij de naam noemen. Ergo, een cursus Europees collectivistisch denken is geboden. Die zou ons kunnen voorbereiden op een toekomst waarin collectivistische identiteit juist voor een demografische meerderheid als de onze een belangrijk, bestendigend machtsmiddel zal blijken te zijn. De tegen massa-moslimimmigratie gekante Oost-Europese EU-lidstaten laten ons tegenwoordig zien met welke levenshouding men volksbehoud vanuit de oude, Avondlandse beschaving zou kunnen bewerkstelligen.

Met name de Balkanvolkeren en -landen hebben zonder Verlichting eeuwen van islamitische aanwezigheid weten te doorstaan. Hongaren, Roemenen, Bulgaren en Serven zijn zich dan ook sterk bewust van hun christelijke en etnische identiteit. Tot ergernis van de verlichte EU zijn zij gekant tegen islamitische immigratie, simpelweg omdat zij het christelijke karakter van hun volkeren willen behouden.

Laat ons ons licht opsteken op de Balkan, bij de Roemenen en de Bulgaren: in september 2015, toen de migranteninvasie iedereen wakkerschudde, zegde Roemenië bij monde van premier Ponta met tegenzin toe om 1.500 migranten op te vangen (net zo veel als het het Nederlandse dorp Hilversum er toen wilde opnemen). Maar het land zwichtte later onder zware druk

Z.H. Patriarch Neofit van Bulgarije

van de EU. In diezelfde maand riep patriarch Neofit namens de Heilige Synode van de Bulgaars-orthodoxe Kerk de eigen regering op geen vluchtelingen meer toe te laten. Hij verklaarde dat het "moreel gezien verkeerd [is] om de Europese grenzen open te stellen voor alle economische migranten en vluchtelingen" en dat migratie vanuit het Midden-Oosten en Noord-Afrika naar Bulgarije vragen oproept over "de stabiliteit en het voortbestaan van de Bulgaarse staat in het algemeen". De kerkelijk leider vervolgde met de stelling dat het bestaande etnisch evenwicht "in ons vaderland Bulgarije, dat ons orthodoxe volk door God beschikt is om er te wonen" ingrijpend kan veranderen als er mensen worden opgenomen die in Europa een beter leven zoeken.

Wij kunnen echter ook ons licht noordelijker opsteken: bij de Polen, Slowaken en Tsjechen. Zij dreven in 2015-2016 de door DuitseWillkommenskultur gebonden EU tot razernij toen zij met Hongarije aangaven liever de grenzen gesloten te houden voor moslims. Het Hongarije van premier Viktor Orbán heeft de migratieroutes vanuit Servië zelfs met een lang grenshek versperd. Orbán denkt dat Europeanen een minderheid in eigen gebied zullen worden als de huidige migrantenstroom aanhoudt. Deze volkeren begrijpen het gevaar van niet alleen islamisering maar van massa-immigratie als geheel; niet enkel omdat zij tot een natiestaat behoren, en niet omdat hun waarden rationeel, inclusivistisch of verlicht zijn, maar omdat zij nog vitale christenen zijn.

Een belerende reactie van Westerse EU-politici hierop is dat de Oost-Europese volkeren "er nog aan moeten wennen multi-etnisch te denken". Die reactie getuigt van Westerse hybris en een beperkte kennis van de Europese geschiedenis. Het waren juist díe volkeren die onder het Habsburgse en het Ottomaanse Rijk moesten samenleven met talrijke etnische minderheden. Alleen al de Roemenen hebben eeuwenlang met Turken, Tataren, Saksen, Zwaben, Ländlers, Hongaren, Szeklers, Serven, Armeniërs, Joden en Zigeuners samengeleefd. Deze situatie duurt tot op heden voort, en men weet zich er etnisch-cultureel geruggensteund.

"Het is dus juist deze langdurige multiculturele toestand die de Oost-Europese volkeren het etnocentrisme heeft verschaft, waar wij lering uit kunnen trekken. "

Het is dus juist deze multiculturele toestand die de Oost-Europese volkeren het etnocentrisme heeft verschaft, waar wij lering uit kunnen trekken. Zij zijn ons voorgegaan in een langdurige staat van multicultuur, zonder de eigen identiteit te verliezen. Het zijn dus wij die nog niet multi-etnisch denken. Maar ook wij kunnen het leren, en wel van deze ervaren volkeren.

Met name de Balkanvolkeren hebben weliswaar Europese ideeën uit de negentiende en begin twintigste eeuw aangegrepen om zich in natiestaten te verenigen. Maar in tegenstelling tot in West-Europa geschiedde deze natievorming relatief onlangs (met de belangrijkste perioden tussen 1848 en 1946). Hun nationalisme was niet, zoals in de 'oude' natiestaten in West-Europa, hoofdzakelijk gebaseerd op de Verlichting (in Frankrijk: Vrijheid, Gelijkheid en Broederschap). Integendeel: Zuidoost-Europees nationalisme was niet rationeel, geseculariseerd, liberaal of burgerlijk. Zuidoost-Europees nationalisme was en is vooral geïnspireerd door de Romantiek (in zekere zin een reactie op de Verlichting) en derhalve gebaseerd op groepsidentiteiten, taal, religie, etniciteit, cultuur en de grond waar die op ontstaan zijn.

Balkanvolkeren voelen zich op allerlei vlakken van het volksleven vertegenwoordigd door hun orthodoxe kerken die zichgedecentraliseerd en langs etnisch-nationale lijnen organiseren, zonder te vervallen in de zonde van het fyletisme: zij zijn Roemeens-orthodox, Bulgaars-orthodox, Servisch-orthodox, Albanees-orthodox, Montenegrijns-orthodox, Grieks-orthodox en Macedonisch-orthodox. Verder is men Reformatus (etnische Hongaren) en buiten de Balkan ben je Pools 'dus' Katholiek, en Russisch 'dus' Russisch-orthodox. Hun nationalisme heeft derhalve een diepe etnisch-culturele en tevens transcedente basis. Zij gebruiken in hun weerwoord op de gevolgen van massa-immigratie niet de term Verlichting, maar wel het wij-woord; 'ons'. Zij beroepen zich op het volk, op de eigenheid, en op de drie G's die zij in het christendom vinden. Orthodoxie biedt richtlijnen; orthodoxe kerken en kloosters hebben op de Balkan door de eeuwen heen bewezen mede een reservoir te zijn voor folkore, nationaal zelfbewustzijn en een stimulans voor etnische trots.

Oost- en Zuidoost-Europeanen weten wat het is om te moeten opkomen voor je etnisch-culturele belangen. Hun geschiedenis zou wel eens ons voorland kunnen zijn. Ons tijdig bewust te zijn van de 'onverlichte', nuttige Oost-Europese groepsstrategieën zal onze volkeren wellicht ten goede kunnen komen.

Volksbehoud

Als er rechten zijn, dan is er wel het recht om over onze eigen toekomst te beschikken. Onze inheemse leefwijze, leefomgeving, cultuur en identiteit dienen in stand te blijven. Dat kunnen we bewerkstelligen door ons te groeperen op een manier die onze oostelijke mede-Europeanen al eeuwen gewoon zijn. Het is nog niet te laat: voor gezin, gemeenschap en geloof hoeven we ons niet tot de islam te richten, maar kunnen we nog terecht bij ons eigen christendom. Bij ons om de hoek, bij wijze van spreken. Volksbehoud is niet iets om ons voor te schamen, integendeel. Ieder ander volk zou zich, eenmaal onder druk gezet, inzetten voor het eigene.

"Onze inheemse leefwijze, leefomgeving, cultuur en identiteit dienen in stand te blijven. "

Ons door de Verlichting en het protestantisme ingegeven gelijkheidsdenken heeft ons uiteraard ook wel goeds gebracht. Andere verworvenheden van de Verlichting als wetenschap, nieuwsgierigheid, wijsbegeerte, vrijheid van meningsuiting en vrijheid van informatie worden terecht geprezen. Ons protestantse arbeidsethos en soberheid hebben onze beschaving tot grootse prestaties gebracht.

Daarentegen heeft het binnen onze oude natiestaten sterk ontwikkelde burgerschapsgevoel ons vertrouwen in de eigen overheden geschonken. Maar aangemoedigd door het verlichte liberalisme laten onze overheden ons nu toenemend in de steek, en beschamen zij ons vertrouwen. Zij dragen ongevraagd de door ons aan hen toegekende regeringsbevoegdheden over aan de Europese Unie. En langzaam maar zeker worden wij als volk vervangen door een nieuwe bevolking met steeds minder gedeelde referentiekaders en cultureel-etnische loyaliteiten. Hoe kunnen wij zonder de eenheid van weleer de komende demografische veranderingen het hoofd bieden? Hoe kunnen wij ons doeltreffend organiseren als we zo geïndividualiseerd zijn geraakt? Wij staan nu voor de keuze: bieden wij die veranderingen met meer of met minder Verlichting het hoofd? Door op liberale wijze de islam meer ruimte te geven, ons als volk te laten ontbinden en onze leefwijze, cultuur en volkswezen te verliezen, of door hen te behouden en te kijken naar de vitale, waakzame, minder verlichte kennis van Oost- en Zuidoost-Europa?

Besluit

De Verlichting verlamt ons op dit ogenblik omdat het ons op de ingezette vervanging van onze volkeren geen ander antwoord verschaft, dan een tegennatuurlijke acceptatie en machtsverlies. Ons liberale bestel redeneert vanuit een oude luxepositie. Het is dus verouderd en boeit ons aan handen en voeten. We moeten af van het idee dat de islam hier dezelfde rechten als het christendom toebedeeld moet krijgen, of dat niet-Europese culturen binnen Nederland gelijk zouden zijn aan inheemse, verwortelde Europese culturen. Dat zijn ze niet. De inzet van elk maatschappelijk debat over de islam moet dan ook zijn dat de islam uit Noordwest-Europa zal moeten verdwijnen en dat moslimimmigratie moet stoppen. Dat moge illiberaal zijn, maar de tekenen des tijds roepen om een krachtdadig signaal: onze inheemse cultuur is weldegelijk te verkiezen boven de uitheemse. De wrijvingen die de multicultuur alhier veroorzaakt bewijzen dat er maar een cultuur leidend en blijvend kan zijn.

" De Verlichting is niet universeel; de aangeboren neiging tot groepsbehoud is dat wel. "

Dezer dagen zien we een vergrote, hernieuwde waardering voor onze eigen folklore, eigen identiteit, geschiedenis en lokale stabiliteit. De massale volkswoede die de afschaffing van de folklorefiguur Zwarte Piet en de vestiging van asielzoekerscentra genereren zijn hoopvolle tekenen. We zien een neiging die weliswaar niet op 'universaliteit' gericht is, maar die wel universeel is, namelijk de reflex tot zelfbehoud onder zelfbewuste gemeenschappen die weten wat ze te verliezen hebben. De Verlichting is niet universeel; die aangeboren neiging tot groepsbehoud – noem het tribalisme of etnocentrisme – is dat wel. Ze biedt ons een sterke, lokale basis die tot voordeel van onze eigen beschaving zal strekken. Wij moeten die tijdig met beide handen aangrijpen, want ze zal met het oog op de voortgaande multiculturalisering ongetwijfeld in intensiteit en belangrijkheid toenemen, en zich een uitingsvorm zoeken.

Het Avondland is ons te zeer 'universeel' en waardenvrij geworden om ons nog lang op de Verlichting en haar politieke exponent, het liberalisme, blind te staren. Immigratie en multiculturalisme zijn geen opties meer, want wij willen nog lang kunnen functioneren op de manier die wij, de meerderheid van dit werelddeel, ons wensen. Nieuwe tijden breken aan. Met of zonder Verlichting.

Geraadpleegde en aanbevolen literatuur

Enkele zaken die ik hierboven heb beschreven zijn ontleend aan boeken, waarvan ik U hieronder graag de titels geef. Zij kunnen ons gedachten aan de hand doen voor het behoud van onze eigen culturele identiteit.

• Elst, Koenraad (1997). De Islam voor Ongelovigen. Wijnegem, België: Deltapers.

• Faye, Guillaume (1998). L'Archéofuturisme. Parijs, Frankrijk: Éditions Æncre. (In 2010 ook in het Engels uitgegeven als Archeofuturism: European Visions of the Post-Catastrophic Age. Verenigd Koninkrijk: Arktos Media Ltd.)

• Faye, Guillaume (2000). La Colonisation de l'Europe: Discours vrai sur l'immigration et l'islam. Parijs, Frankrijk: Éditions Æncre.

• Goudsblom, Johan (1960). Nihilisme en Cultuur. Amsterdam, Nederland: Arbeiderspers.

• Hitchins, Keith (2009). The Identity of Romania. Boekarest, Roemenië: Editura Enciclopedică.

• Hösch, Edgar (2002). Geschichte der Balkanländer: Von der Frühzeit bis zur Gegenwart. München, Bondsrepubliek Duitsland: Verlag C.H. Beck.

• Hupchick, Dennis (2004). The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. New York, Verenigde Staten: Palgrave Macmillan.

• MacDonald, Kevin (2007). Cultural Insurrections: Essays on Western Civilization. Verenigde Staten: Occidental Press.

• Scruton, Roger (2010). Het Nut van Pessimisme en de Gevaren van Valse Hoop. Amsterdam, Nederland: Uitgeverij Nieuw Amsterdam.

• Scruton, Roger (2003). Het Westen en de Islam. Antwerpen, België: Uitgeverij Houtekiet.

• Smith, Anthony (1998). Nationalism and Modernism. Londen, Verenigd Koninkrijk: Routledge.

• Tocqueville, Alexis de (2011). Over de Democratie in Amerika (oorspr. 1840). Rotterdam, Nederland: Lemniscaat Uitgeverij.

10:47 Publié dans Philosophie, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : idéologie des lumières, lumières, aufklärung, verlichting, philosophie, philosophie politique, occident, islam, théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 20 mai 2013

The Enlightenment from a New Right Perspective

The Enlightenment from a New Right Perspective

By Domitius Corbulo

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

“When Kant philosophizes, say on ethical ideas, he maintains the validity of his theses for men of all times and places. He does not say this in so many words, for, for himself and his readers, it is something that goes without saying. In his aesthetics he formulates the principles, not of Phidias’s art, of Rembrandt’s art, but of Art generally. But what he poses as necessary forms of thought are in reality only necessary forms of Western thought.” — Oswald Spengler

“Humanity exists in its greatest perfection in the white race.” — Immanuel Kant

Every one either praises or blames the Enlightenment for the enshrinement of equality and cosmopolitanism as the moral pillars of our times. This is wrong. Enlightenment thinkers were racists who believe that only white Europeans could be fully rational, good citizens, and true cosmopolitans.

Leftists have brought attention to some racist beliefs among Enlightenment thinkers, but they have not successfully shown that racism was an integral part of Enlightenment philosophy, and their intention has been to denigrate the Enlightenment for representing the parochial values of European males. I argue here that they were the first to introduce a scientific conception of human nature structured by racial classifications. This conception culminated in Immanuel Kant’s anthropological justification of the superior/inferior classification of “races of men” and his “critical” argument that only European peoples were capable of becoming rational and free legislators of their own actions. The Enlightenment is a celebration of white reason and morality; therefore, it belongs to the New Right.