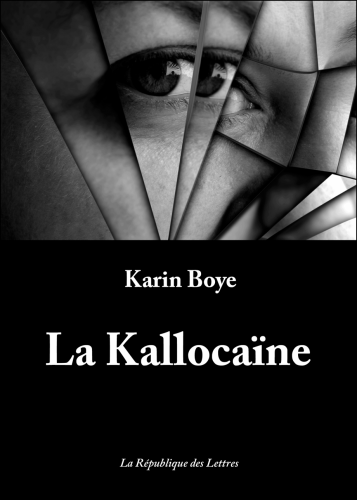

La Kallocaïne (1940) : un roman prophétise l'État mondial

par Benjamin Kaiser

Source: https://sezession.de/69354/kallocain-1940-ein-roman-prophezeit-den-weltstaat

Des conditions sociales poussées à l'extrême, telles que l'actuelle "bigarrure et diversité", peuvent-elles vraiment être conservées durablement ?

C'était et c'est toujours une question centrale que l'écrivaine suédoise Karin Boye a abordée dans son classique de science-fiction La Kallocaïne, publié en 1940, un texte précurseur important du 1984 de George Orwell.

Le personnage principal du roman est le chimiste Kall, un père de famille bien établi, citoyen loyal de l'État mondial totalitaire et chercheur dans la ville chimique n°4. En tant que lecteur, nous écoutons avec étonnement son monologue intérieur, qu'il censure constamment devant nous et devant lui-même, afin de ne pas sortir du corset étroit de ce qui est autorisé par la pensée.

Après de longues années de recherche, Kall (qui signifie "froid" ou "insensible" en suédois) met au point la kallocaïne, une drogue de la vérité qui oblige toute personne à qui elle est injectée à révéler sans réserve toutes ses pensées, ses sentiments et même toute sa vie intérieure. Avide de reconnaissance, il est impatient de mettre son invention en pratique et de la mettre au service de l'État mondial, de sorte que les hautes fonctions de l'État ne puissent être attribuées qu'après un entretien sous l'influence de la drogue. L'objectif est d'éviter que des personnes manquant de loyauté n'accèdent à des postes élevés:

"'J'espère que cela profitera à l'État', ai-je dit, 'une drogue qui aide chaque personne à révéler ses secrets, tout ce qu'elle a jusqu'ici gardé pour elle en silence par honte ou par peur'".

Quant à savoir si l'invention d'une telle drogue pourrait avoir des conséquences négatives dans un état de surveillance, c'est une question que Kall ne se permet de poser à aucun moment. Il devient donc méfiant lorsque son supérieur, Rissen, ose suggérer les conséquences possibles d'une telle invention avec une remarque pointue:

"Vous semblez avoir une conscience inhabituellement bonne", dit sèchement Rissen, "ou bien faites-vous semblant ?".

Les rares conversations de Kall avec sa femme Linda nous montrent qu'elle aussi est nettement plus clairvoyante que lui et que, même si elle se tait la plupart du temps pour des raisons politiques, elle est consciente que derrière le masque de bon citoyen du monde, il n'y a pas que l'adhésion à l'idéologie officielle.

Le "matériel humain" pour la première série d'essais de la drogue de la vérité, la kallocaïne, provient du "Service des victimes volontaires", un groupe au sein de la ville chimique n°4, auquel les citoyens se joignent généralement à l'adolescence après avoir regardé des films de propagande et qui se mettent dès lors à disposition comme cobayes pour des expériences scientifiques. Ils ne vivent pas très longtemps, car les expériences médicales menées sur eux leur causent de graves problèmes de santé. Néanmoins, leur apparence extérieure est idéologiquement entièrement dévouée à l'État mondial.

Le premier sujet sur lequel la nouvelle drogue, la kallocaïne, est testée est le numéro 35. Il se présente au laboratoire avec un bras en écharpe et n'a plus l'air très en forme. Kall se plaint à Rissen qu'il aimerait avoir du matériel plus frais, mais celui-ci lui explique qu'il n'y a plus personne : il y a eu tellement d'expériences avec des gaz toxiques ces derniers temps.

Sous l'influence de la kallocaïne, le numéro 35 déclare qu'il ne s'est jamais senti aussi bien, que la drogue le libère enfin de toutes les contraintes intérieures, mais tout le reste ressort: la peur, le désespoir et le fait qu'il ne puisse pas trouver de femme en tant que membre du "Service des victimes volontaires". Presque étonné, Rissen note que Kall est sérieusement horrifié par les révélations du numéro 35 et doit intervenir pour que Kall ne signale pas à la police l'insubordination politique que le numéro 35 exprime sous l'influence de la drogue de la vérité.

Alors que les interviews suivantes se déroulent de manière très similaire et que Rissen continue à empêcher Kall de les signaler, un sujet finit par faire une déclaration lourde de conséquences. Kall s'impose alors et fait appel à la police.

Des informations incompréhensibles ont filtré, l'un des sujets a admis que des groupes de personnes mystérieuses se réunissent et ne font que se taire lors de leurs rencontres. Ni Kall ni la police ne parviennent à trouver une explication : des personnes qui s'assoient simplement ensemble sans se dire un seul mot :

"Une autre personne, également une femme, a finalement pu nous donner quelques noms. Nous avons donc pensé que nous pourrions lui mettre une pression particulière en lui demandant quelle organisation se cachait derrière tout cela. Sa réponse était tout aussi déroutante que celle des autres".

"Nous ne cherchons pas à être organisés", a-t-elle déclaré. Ce qui est organique n'a pas besoin d'être organisé. Vous construisez de l'extérieur, nous sommes construits de l'intérieur. Vous avez construit avec vous-mêmes, comme si vous étiez des pierres, et vous vous désagrégez de l'extérieur, vers l'intérieur. Nous sommes construits de l'intérieur, comme des arbres, et entre nous poussent des ponts qui ne sont pas faits de matière morte et de contrainte morte. C'est de nous que sort le vivant. A travers vous, c'est l'inanimé qui pénètre".

A la fin, c'est l'épouse du protagoniste Kall qui se rend compte que l'Etat total et l'utopie sociale qu'il maintient ne sont invincibles qu'en apparence, mais qu'ils sont menacés d'effondrement à tout moment à l'intérieur, car la masse des gens rejette consciemment ou inconsciemment l'Etat total.

Pour Boye, les conditions sociales créées artificiellement et poussées à l'extrême - qui ne peuvent être maintenues qu'au moyen de la violence et de la manipulation étatiques - sont donc une cause essentielle de l'émergence de systèmes totalitaires. Plus un état social est extrême, plus il s'est éloigné du droit naturel, plus l'effort que l'État doit fournir pour conserver cet état "d'utopie sociale" est important.

L'utopie actuelle "bigarrée et diversifiée" de la République fédérale se voit elle aussi de plus en plus exposée à ce dilemme, malgré ou justement à cause de son "ordre fondamental libéral et démocratique" bruyamment propagé par les médias. Après des décennies de travail préparatoire, le pendule a penché vers l'extrême-marxisme culturel ; maintenant, la société, dans son inertie naturelle, voudrait revenir dans l'autre sens - et voilà que le brouhaha des ivrognes devient un cas pour la protection de l'Etat.

Pour préserver une utopie sociale, il faut donc aussi diriger les pensées et les sentiments. C'est pourquoi, dans les premières pages du roman, Kall vante son invention à la gouvernante de la famille, qui l'espionne en même temps officiellement pour le compte de l'État mondial :

"Les pensées et les sentiments donnent naissance aux mots et aux actes. Comment les pensées et les sentiments pourraient-ils donc être l'affaire privée de l'individu ? ... A qui appartiennent donc les pensées et les sentiments, si ce n'est à l'Etat" ?".

George Orwell a également décrit ce phénomène de manière similaire en mai 1941 dans son émission "Littérature et totalitarisme" ; à savoir que

les États totalitaires visent toujours à contrôler par tous les moyens les pensées et les sentiments de leurs habitants au moins autant que leurs actions.

Aujourd'hui encore, lorsqu'on tente d'arrêter le mouvement de balancier, on constate que l'État veut de plus en plus savoir si le citoyen est loyal envers l'utopie à préserver, non seulement en ce qui concerne l'attitude extérieure, mais aussi et surtout en ce qui concerne l'état d'esprit. L'effacement des différences entre les paroles et les actes par des constructions linguistiques telles que le "discours de haine" est symptomatique de ce phénomène, ce qui a créé devant les tribunaux allemands la situation absurde où la fausse opinion est devenue une "violence" linguistique et est de plus en plus souvent punie plus sévèrement que l'acte de violence réel.

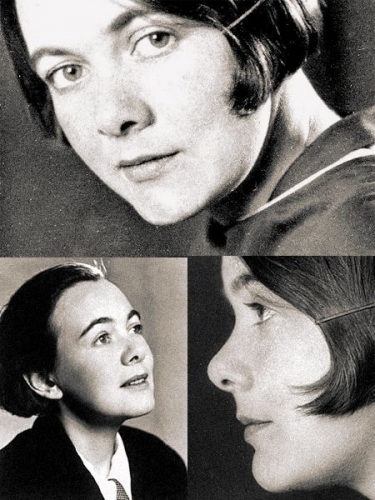

Le fait que Boye, l'une des premières lesbiennes avouées du 20ème siècle, jouisse d'un statut culte dans les "études de genre" ne devrait d'ailleurs pas décourager la lecture de son roman oppressant et génial. Au contraire. Kallocain a été écrit après avoir visité l'Union soviétique et l'Allemagne nazie. Ces deux expériences ont été décisives pour Kallocain.

Alors que Boye a visité l'Union soviétique en tant que jeune socialiste et en est repartie profondément désillusionnée, les spectacles de masse du national-socialisme en Allemagne ont dû la fasciner d'une autre manière, elle qui vivait avec une juive allemande. Sa biographe Margit Abenius décrit la visite d'un rassemblement avec un discours de Goering au Palais des sports:

"Scharp a regardé Karin se tenir là, le bras tendu, complètement fascinée, et faire le salut hitlérien".

Plus tard, elle a écrit à propos de cette expérience que les émotions politiques éruptives avaient "déclenché des crises nerveuses chez les jeunes". Et à l'instar de la croissance de l'intérieur décrite dans le roman, Boye a plus tard nié avoir "écrit" Kallocain, affirmant que le roman avait plutôt été écrit à travers elle, qu'elle s'était vécue comme une "receveuse" en l'écrivant.

Kallocain s'inscrit, selon la littérature officielle, dans la lignée des grands "romans de science-fiction post-chrétiens" (Erika Gottlieb), des dystopies dans lesquelles la question chrétienne du salut éternel ou de la damnation est devenue une question séculière. Commençant par le roman Nous d'Evgueni Zamiatine, traduit pour la première fois dans des langues occidentales en 1924, qui traduisait en dystopie l'utopie du communisme réel de l'Union soviétique, suivi par Le Meilleur des mondes d'Aldous Huxley (1932) et 1984 de George Orwell (1949), le roman de Boye va au-delà de tout cela.

Considérée comme l'un des plus grands écrivains suédois (un cratère de Vénus porte son nom), Boye est passée du bouddhisme au christianisme alors qu'elle était encore étudiante. Elle en a cependant souffert toute sa vie en raison de son homosexualité, ce qui l'a conduite à des conflits intérieurs qu'elle a exprimés dans de nombreux poèmes. Prisonnière de ce conflit qu'elle jugeait insoluble, elle écrivit à son amie Agnes Fellenius :

"Je croyais voir le monde sous un jour nouveau - sous le signe de la croix, de la souffrance par procuration. La croix de Dieu s'étend à travers tous les âges et tous les espaces. Et qu'est-ce que la sainte communion sinon une initiation à la croix, la nouvelle union avec Dieu: on s'initie soi-même pour ensuite prendre sur soi, à cause de Lui, une partie de Sa souffrance éternelle - pour combattre le combat de Dieu dans le monde : cela s'accompagne d'une grande douleur".

Et non, Kallocain ne connaît pas de message ouvertement chrétien et pourtant, il y a plus en sous-cutané lorsque l'individu est placé devant le choix de se conformer et de sacrifier toute spécificité à l'utopie sociale ou de prendre le chemin de la dissidence et d'y laisser sa vie: il s'agit également d'une initiation. En effet, puisque dans un État qui veille lui-même au respect de la pensée correcte, le monde intérieur n'est plus un lieu d'évasion, il ne reste à l'homme que le silence spirituel. Et cela rappelle le mystique médiéval Heinrich von Seuse, que seule la sérénité dans le silence peut donner naissance à une nouvelle vision du monde qui brise toutes les entraves.

Et c'est ainsi que les citoyens de l'État mondial interrogés sous l'influence de la drogue parlent du fait que l'expérience du silence leur redonne une initiation qui leur fait voir les choses autrement et les "éveille" à un état de connaissance spirituelle qui, du point de vue de l'État, est irréversible :

"'Tu as parlé d'initiation', répondit Rissen à la femme, sans me prêter attention. 'Comment les gens sont-ils initiés ?".

"Je ne sais pas. Cela se produit simplement. Tout d'un coup, et puis c'est toi. Les autres le remarquent, ceux qui sont aussi initiés".

"Donc n'importe qui peut venir et dire qu'il est initié ? Il doit y avoir un rituel, une cérémonie - il n'y a pas d'initiation à un quelconque secret?".

"Non, rien de tout cela. C'est quelque chose que vous remarquez de vous-même, vous comprenez ? Pensez-y comme suit : soit vous l'êtes, soit vous ne l'êtes pas - et certaines personnes ne font jamais cette expérience".

Mais comment le remarque-t-on ?

'Eh bien, on le remarque en tout - à la vue d'un couteau, et quand on dort, et quand cela vous vient à l'esprit avec une sainte clarté - et beaucoup d'autres choses -'"

* * *

Karin Boye : La Kallocaïne - à commander ici: https://www.babelio.com/livres/Boye-Kallocaine/804983

Résumé :

Dans une société où la surveillance de tous, sous l’œil vigilant de la police, est l’affaire de chacun, le chimiste Leo Kall met au point un sérum de vérité qui offre à l’État Mondial l’outil de contrôle total qui lui manquait.

En privant l’individu de son dernier jardin secret, la kallocaïne permet de débusquer les rêves de liberté que continuent d’entretenir de rares citoyens. Elle permettra également à son inventeur de surmonter, au prix d’un viol psychique, une crise personnelle qui lui fera remettre en cause nombre de ses certitudes. Et si la mystérieuse cité fondée sur la confiance à laquelle aspirent les derniers résistants n’était pas qu’un rêve ?

On considère La Kallocaïne, publié en 1940 en Suède, comme l’une des quatre principales dystopies du XXe siècle avec Nous autres (Zamiatine, 1920), Le Meilleur des mondes (Huxley, 1932), et 1984 (Orwell, 1949).

Nouvelle traduction intégrale. Traduction du suédois par Leo Dhayer.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg