Krzysztof Urbanek

Adversus Haereses: Nicolás Gómez Dávila - Against the Religion of Democracy¹

Ex: https://sidneytrads.com

I

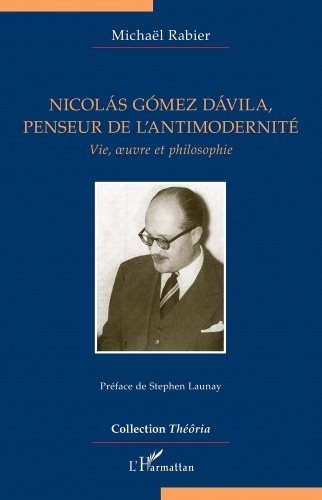

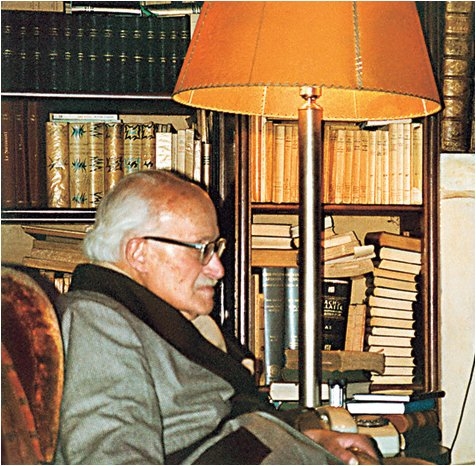

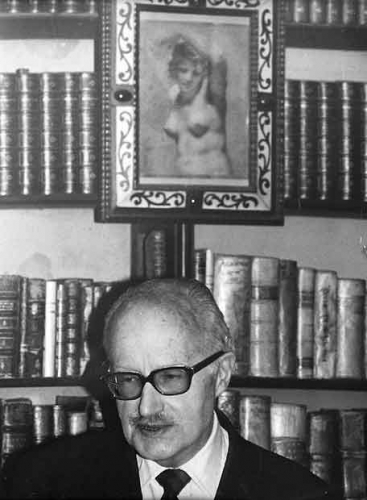

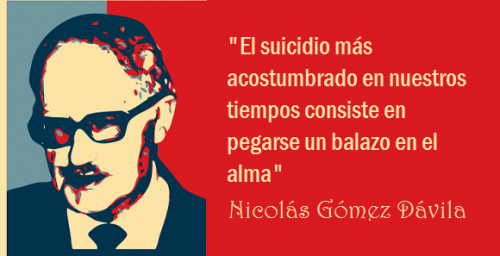

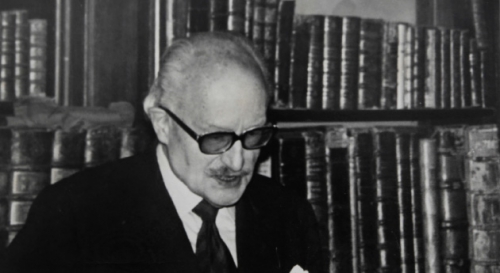

Nicolás Gómez Dávila2 is primarily known for his authorship of the five volume work Scholia to an Implicit Text. Those who study Dávila’s life and work mostly focus on these 10,260 aphorisms3 and question what the “implicit text” actually is. Various arbitrary answers are offered by different academics: Franco Volpi believes it is the ideal act which is beyond the Bogotán’s creative reach, Till Kinzel believes it is the books from his library, Francia Elena Goenaga Olivares believes it is God, and numerous other researchers believe that the “implicit text” is Western culture itself.

However, it is rarely asked whether the Author of the Scholia has not elucidated an answer to this himself. Indeed, it appears that in 1988 – thus during the thinker’s life – Francisco Pizano de Brigard (who was a friend of Dávila’s) noted in a special edition of Revista del Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario4 that the “implicit text” appears on pages 60-100 of the first volume of the Textos I.5 There is no evidence that Dávila ever objected to this. Moreover, in the first volume of the Scholia we encounter the Bogotan’s idiosyncratic note: “the writer’s original thought echoes in his passing commentaries.”6

This point is sufficiently pressing to call for a closer reflection on the abovementioned text in order to capture its essence, because the substance of one of the most ingenious works of twentieth century thought revolves around the ideas contained in Dávila’s Scholia to an Implicit Text.

II

The subject of Nicolás Gómez Dávila’s Text Implicite is democracy. According to the Author, democracy is a new religion; more precisely, an anthropotheistic religion in which Man is presented as God. The Catholic Thinker therefore concludes that the ultimate consequence can only be to treat democracy as if it were a form of Satanism.

The subject of Nicolás Gómez Dávila’s Text Implicite is democracy. According to the Author, democracy is a new religion; more precisely, an anthropotheistic religion in which Man is presented as God. The Catholic Thinker therefore concludes that the ultimate consequence can only be to treat democracy as if it were a form of Satanism.

At the beginning of his thesis, Dávila concerns himself with two main types of democracy: bourgeoisie democracy and people’s democracy. To the Bogotán, the difference between the bourgeoisie and peoples democracies is essentially trivial, give that both strive towards the same goal, namely “the redemption of Man though Man.”

According to the Author of the Scholia, democracy is neither an electoral procedure, nor a social structure, nor an economic order. History illustrates that democracy is accompanied by militant secularism and the criticism of the mere phenomenon of religion. The intent that underpins the secularisation of society emanates from a “Godless zeal” and “secular caution”.7 Students of democracy highlight its religious character: that the sociology of democratic revolutions operates in categories that have been established through religious historicism. Certainly, the religious aspect of democracy is illuminated – I would say rationalised – equally through the bourgeoisie capitalist systems as well as through the peoples’ communistic systems. Gómez admits the primacy of the later8 and adds that while its theories hold that it is the best exemplification of truth, “it could be said that it suffices to reverse [these communistic theories] to not fall into error.”9

Next, Gómez turns his attention to the philosophy of history. He holds that “every philosophy aims to define the relationship between Man and his deeds.”10 He adds, that “the manner in which the relationship between Man and his deeds is defined, determines all universal explanations [i.e. for human conduct]”,11 and “philosophical definition of a particular relationship [i.e. between Man and deed] constitutes a theory of human motivation.”12 The Bogotán considers the plurality of the theories of motivation and their successive or simultaneous application, yet he concludes that “in each motivational theory, to which one may be preferentially disposed, and in each configuration in which he may be found, every deed is coordinated by an earlier religious choice.”13 This original choice – which Man is often oblivious to – defines Man’s attitude towards God and is the ultimate context of the deed. Thus Gómez summarises that “the individual as a historical phenomenon is the product of a religious choice.”14

The Bogotán therefore continues that “as we study any democratic phenomena, only a religious analysis will explain its nature, and thus allow one to ascribe to it appropriate meaning.”15 His definition of democracy appears at this point of reflection: “Democracy is an anthopotheistic religion. Its principle is a choice which has a religious character, a deed in which Man acknowledges Man as a god. Its doctrine is the theology of Man-as-God, its praxis is the realisation of the principle in behaviour, institutions and deeds.”16 Thus Gómez holds that “a godliness that democracy ascribes to the individual […] is a strictly theological definition”17 and therefore “democratic anthropology treats Man’s being in a manner that accords with classical attributes of God.”18

According to the Author of the Scholia, anthopotheism opts for one of two solutions to our present miseries. Either it speaks of a godly past (Orphic cosmogonies or Gnostic sects), or a godly future (democratic religion). Modern democratic religion is a lesson in “painful theogony”,19 and Man is represented as “material for its future condition.”20 Gómez speaks of the ethical lawlessness of anthropotheism, of it sectarianism, and its metaphysical revolt. In the next stage of his reflection, he underlines that “democratic doctrine is an ideological superstructure, patently applied to religious assumptions. The anthropological bias of the democratic doctrine finds its continuation in a militant apologetics.”21 In relation to democratic anthropology, Man is represented by Will, a Will that is free, sovereign and equal. Gómez briefly describes four theses of the democratic ideology’s apologetics:

- Pompous atheism (theology of the immanent God);

- Progressivism (the idea of progress as theodicy: from matter through Man towards the Devine);

- Subjective axiology (value recognised as that which the Will considers its own); and

- Common determinism (“total human freedom demands an enslaved universe”22).

According to Nicolás Gómez Dávila, the sovereign Will reigns in liberal and individualistic democracies, while the authentic Will reigns in collective and despotic democracies. In his characterisation of the democratic religion, the Author of the Scholia holds that “the transformation of a liberal and individualistic democracy, into a collective and despotic democracy, does not molest the democratic intention, nor does it depart from its promised objectives.”23 This is because the law of the democratic Will has the mandate to coerce the obedience of the individual Will, due to the fact that the individual Will “sins against its [i.e. the democratic Will’s] own being.”24 Summarising thus far, the Bogotán writes that “continued faith in the democratic ideal interferes with the immediate objectives of the authoritarian democrat, who enslaves in the name of freedom and awaits the coming of a god from without the depraved masses.”25 Thus in the context of Man’s supposed omnipotence, Gómez recalls democracy’s resulting abuse of technology and the “inexorable industrial exploitation of the planet.”26

According to Nicolás Gómez Dávila, the sovereign Will reigns in liberal and individualistic democracies, while the authentic Will reigns in collective and despotic democracies. In his characterisation of the democratic religion, the Author of the Scholia holds that “the transformation of a liberal and individualistic democracy, into a collective and despotic democracy, does not molest the democratic intention, nor does it depart from its promised objectives.”23 This is because the law of the democratic Will has the mandate to coerce the obedience of the individual Will, due to the fact that the individual Will “sins against its [i.e. the democratic Will’s] own being.”24 Summarising thus far, the Bogotán writes that “continued faith in the democratic ideal interferes with the immediate objectives of the authoritarian democrat, who enslaves in the name of freedom and awaits the coming of a god from without the depraved masses.”25 Thus in the context of Man’s supposed omnipotence, Gómez recalls democracy’s resulting abuse of technology and the “inexorable industrial exploitation of the planet.”26

Next, Gómez come to an historical outline in which he discusses the historical legacy of democratic anthropotheism. He comes to the conclusion that the “modern democratic religion comes into being when Bogomilian and Cathar dualism, and apocalyptic messianism, fuse together.”27 Through a century of evolution, the democratic religion – the “daughter of pride”28 – begets a tremendous number of subsequent ideologies:

All can deceive us: virtue, which dazzles itself, sin, which deforms itself before our eyes. For the whole doctrine to be accepted, all that is required is that one aspect flatter us. When we fall into the enslaving trap, the seemingly chaotic nature of our conduct is then subject to the pressures [i.e. of the ideology] that purports to enforce order.29

Here we see the multiplicity of pathways each of which lead to the same destination: the deification of Man. The Author of the Scholia argues that the watershed moment in the evolution of the democratic religion was the formation of the nation-state, “which believes itself to be the sole judge of its deeds and the ultimate arbiter of its affairs […] which it accepts only those norms which are acknowledged by its own Will, and whose interests is the highest law.”30 According to the Bogotán, “the sovereign nation is the first democratic victory.”31 The only response to this usurpation is to assert the Divine Right of Kings. Such a law will eliminate any absolutizing tendencies: “above the Monarch is the Monarch Most High – shall rain judiciously, anointed by religion, preceded by natural law, guided by the authority of morality.”32

The next stage of the democratic invasion, which justified through the nature of its doctrine, is the mass’s revolutionary demand for freedom. According to Gómez, this way “the masses demand the freedom to be their own tyrant.”33 Equally important is that as soon as the mass’s demands are met, the axiological ties that underpin economic dynamism are destroyed, and the desire for unlimited wealth and prosperity arises. This economic value is subject to the suzerainty of Man, and in Gomez’s opinion, it “is the least absurd symbol of Man’s imaginary sovereignty.”34 The cult of wealth is a typically democratic phenomenon associated with the dominance of the bourgeoisie. Thus the bourgeoisie consciously elects to create and support the existence of a secular state, so as to avoid having to resolve the opposition between his subjective whims against the “interfering axiology”35 of objective or perennial truths:36

[W]hoever tolerates the proposition that the religious perspective interferes with the pursuits of banal materialist or worldly affairs, that ethical righteousness can arrest technological progress, that an aesthetic cause can modify political initiatives and projects, such a person wounds that bourgeoisie sensitivity and betrays the bourgeoisie enterprise.37

In the democratic religion, each individual is granted the superficial authority over his own destiny. Everything is to be subject to the individual’s capricious will. Gómez writes that “economic theft [i.e. when the individual’s right to the fruit of his labour is abrogated, or when the aforesaid axiological ties that underpin economic dynamism are destroyed.] culminates in a pusillanimous individualism, in which ethical indifference is reflected in intellectual anarchy.”38 The Bogotán observes that “reactionary apprehension, which every democratic episode provokes, recreates a theory of human rights and political constitutionalism, so as to contain and restrain the mischievousness of people’s sovereignty.”39 In this context, Gómez recalls the weaknesses of political liberalism. Thus, “[t]he third phase of the democratic conquest is the establishment of the communistic society.”40 Communism, according to the Author, is a conscious project, and

in the communist society, the ambition of the democratic doctrine is revealed. Its goal is not the modest happiness of existing humanity: it’s goal is the recreation of a Man whose sovereignty assumes the omnipotent control over his universe. Communist Man is a deity, who treads on the earthen crust.41

In conclusion, Gómez writes about the resulting ennui and cruelty of Man who attempts unsuccessfully to imitate the omnipotence of God,42 and considers the total reactionary rebellion to be the only sincere response to the anthropotheistic democratic religion.43

Generally speaking, so much on the topic of anthropotheism can be found in the 1959 volume of the Textos. It is worth noting inter alia that in his text Implicite Gómez focuses on futuristic anthropotheism: i.e. the democratic religion itself. Furthermore, while searching for the roots of this democratic religion, he arrives at an anthropotheism fixated on Man’s deified past, or in other words, on Gnosticism. The extent to which there are commentaries concerning Gnosticism in the New Scholia to an Implicit Text,44 these are related to and contingent on the critique of democracy itself in the Scholia to an Implicit Text. It is clearly evident that on reflection, and after a period of omitting to address the issue, Nicolás Gómez Dávila places considerable weight on Gnosticism: this can be found in the overlapping boundaries of religion and philosophy. Moreover, the student can notice that during this period, Gómez departs from a clear distinction marked in his Textos, and all anthropotheism – both past and futuristic – is identified with Gnosticism itself.

In light of the above, it is unsurprising that the Bogotán treats Gnosticism with decisive enmity. The advocates of Gnosticism are apparently considered the greatest enemies of Christianity, and from this perspective he identifies the active threat of its contemporary manifestation: “Christianity should not be defended from the ‘arguments’ of past and present scientism, but against the Gnostic poison.”45 Let us attend to what Gnosticism is historically, and contemplate whether or not Gómez is mistaken when speaking of its toxicity.

III

‘Gnosticism’ is the label for numerous currents of thought which are based on the knowledge of divine secrets, that are exclusively reserved for an elite. Gnosticism calls for salvation through a higher awareness that is obtained by way of an internal enlightenment. Here we see a so-called ‘self-redemption.’ Gnosticism developed in the second and third century after the birth of Christ in the eastern provinces of the Roman Empire. It is a syncretic creature which combines many elements common to Hellenic philosophy as well as Judaism and Christianity. The rise of the main current of Gnosticism (whose creators include Basilides of Alexandria, Valentinus of Phrebonis and Marcion of Sinope) is preceded by a pre-Christian gnosis, for example, the Judaic apocalyptic of Qumran, various exotic doctrines of Iranian and Indo-Iranian origin, specific currents of Orphism, as well as neo-Pythegorianism and Platonism.

The geneology of Gnosticism is not foreign to Gómez: “the birth of gnosis can evidently be traced to the pre-Christian era, yet its poison has evolved in the shadow of Christianity.”46 Thus the Bogotán ceases to associate Platonism – to which he is endeared – with Gnosticism and directs his suspicions towards Stoicism47 – which he despises: “The Greek roots of Gnosticism spätantike are not found in Platonic dualism but in Stoic monism.”48

The geneology of Gnosticism is not foreign to Gómez: “the birth of gnosis can evidently be traced to the pre-Christian era, yet its poison has evolved in the shadow of Christianity.”46 Thus the Bogotán ceases to associate Platonism – to which he is endeared – with Gnosticism and directs his suspicions towards Stoicism47 – which he despises: “The Greek roots of Gnosticism spätantike are not found in Platonic dualism but in Stoic monism.”48

Returning to the general principles of Gnosticism, a closer inspection reveals that it can be characterised by the belief in Man’s god-like nature, and while he is often oblivious to this supposed nature, he nonetheless labours to obtain knowledge thereof. According to Gnosticism, the gnostic who thus labours, as well as the divine essence and the gnosis through which knowledge of it is sought, are all consubstantial.49 In other words, the divine aspect of Man’s personality is “dormant” until the moment that the redemptive gnosis has been attained, until the moment that Man becomes aware of his divine essence. In this context, Gómez observes that “the awareness of the Gnostic’s divine nature can be redemptive only when it is the deed of the subject50 when the subject recognises within himself a redeemed being. | Gnosis is idolatry.”51 Thus the continuation of Gnosticism is the Enlightenment and its rationalist programmes: “Only ignorance imprisons the divine nature of Man. This divine nature remains in a state of Fall [i.e. “dormancy” as per ibid.] until it has attained awareness of its divinity. Aufklärung [i.e. Enlightenment] is the careful exposition of Gnosis.”52 “Rationalism is the official sobriquet of Gnosticism.”53 According to the Author of the Scholia, Enlightenment’s faith in progress is connected to the auto-deification of Man: “‘Progress’ is the name of a process in which salvator-salvandus54 restores its Fallen divinity.”55 I believe that on the same philosophical56 basis, it would be appropriate to elucidate Gómez’s antipathy towards Hegel: “Goethe is a pantheist. Hegel is a Gnostic | Pantheism is a slope, only Gnosticism is a cliff edge”57 and “Nietzsche is barely uncivil – Hegel is blasphemous.”58 Now, we may come to learn what the Bogotán believes to be the difference between pantheism and Gnosticism. He writes that:

Because the substance of the matter which is to be understood directly is more important than its form, we need to differentiate naturalist mysticism and personal mysticism from theistic mysticism: likewise we need to differentiate the experience of a pristine world and the experience of the eternal ‘I’ from the experience of the reality of God.

Theistic mysticism is not susceptible to corruption. While naturalistic mysticism degenerates to pantheism, as the ecstatic awareness identifies the pure act of creation with the splendour of the Creator. Moreover, personal mysticism degenerates into Gnosticism, where one is steeped in self-awareness identifies the eternal soul with the perennial God.

The pantheistic attitude is less sinful than Gnostic attitudes because, in the former, Man’s pride is engulfed in the divine conflagration [i.e. of life]. However, an erroneous interpretation of mystic experience leads to a repetition of the sacrilegious.59

Gnostics believe that primordial Man is enslaved by the Demiurge and his worldly powers, as well as his flesh which is the prison of the divine spirit. Thus, redemption occurs by way of liberation from the mundane world and the corporeal flesh. “The Gnostic deification of the soul occurs when the merger of Neoplatonism and Mazdaism automatically results in the unification of Evil and materialism.”60

In the second century A.D., Gnosticism was customarily concerned with the Fall of the divine entity; Manicheanism, associated with the gnostic dualist religious currents begotten by Mani in the third century A.D., concerned itself with the duality of and struggle between Good and Evil. After contact with Christianity, Gnosticism assumed the religious elements of Judaism and Christianity, e.g. revelation per se, and in particular the revelation of Christ and the revelation contained in the Scriptures. In the womb of Christianity, Gnosticism stimulates numerous heresies (e.g. Valentinius of Phrebonis and his disciples). Manichaeism is presented as a continuation of Gnosticism, and the inheritors of both currents are the Pualines, Bogomils and Cathars. Gómez does not fully agree with this classification and seems to contradict it, as he earlier writes in Textos I:

In the second century A.D., Gnosticism was customarily concerned with the Fall of the divine entity; Manicheanism, associated with the gnostic dualist religious currents begotten by Mani in the third century A.D., concerned itself with the duality of and struggle between Good and Evil. After contact with Christianity, Gnosticism assumed the religious elements of Judaism and Christianity, e.g. revelation per se, and in particular the revelation of Christ and the revelation contained in the Scriptures. In the womb of Christianity, Gnosticism stimulates numerous heresies (e.g. Valentinius of Phrebonis and his disciples). Manichaeism is presented as a continuation of Gnosticism, and the inheritors of both currents are the Pualines, Bogomils and Cathars. Gómez does not fully agree with this classification and seems to contradict it, as he earlier writes in Textos I:

Paulinism is closer to the Marcionite doctrines than the Manichean, therefore, as with Bogomilism and equally as in Catharism, Gnostic elements are likely the result of a contamination resulting from the blending of the two.

Gnosticism crystallises on the conventicles of the ‘free spirit’ and Amalric pantheism.61

In any case, the subject of Gnosticism is the attainment of secret knowledge, and its aim is an Enlightenment which is achieved through the revelation of mystic knowledge, where such revelation thus becomes the objects of secret wisdom. Gnostics derive this wisdom from Christ and his prophets, in opposition to faith (in particular Christian faith). Gnosis evolves in centres of Christian communities, particularly within those in which adherents to foreign beliefs can be encountered (Ephesus, Syria and Alexandria). The secret wisdom of Gnosis stands in opposition to naturalism, occultism and the magic of Christian Revelation. Its goal is the exaltation of Man’s hidden natural powers, the demotion of Christ to the role of but one in many unique historic individuals. In this context, it is worth noting Hebrew Docetism, i.e. the questioning Christ’s apparent humanity. Gómez clarifies: “Docetism takes as its beginning not the disdain to matter, but in the desperate need for the transformation of the Redemptor into a mundane vehicle of revelation. | Christ does not redeem Docetism, he evokes it.”62

Syrian Gnosis (centred in Antioch) derives from Simon Magus of Samaria (described by the Fathers of the Church as ‘the Father of all Heresies’). Simon claims that fire is the primordial principle (God acts through fire – reminiscent of the Burning Bush). This God-Fire is no simple concept. It is constituted by two elements: the male (mind) and feminine (thought). From God come the six roots of the Eons (cosmic powers) as well as a seventh, which is present in all, a power known as ‘Father’. The Father begets the world and the reigning six Eons, and a seventh power, which is the ‘Spirit’. According to Simon Magus, matter is not created, it is eternal and shaped by the Demiurge, who is an Angel sent by the Highest God. While Man is formed by Good as well as Evil powers, and thus is naturally corrupted, he is in need of redemption. Simon holds that the world requires redemption though the male element (himself) and the female element (Helen, a prostitute from Tyre63). Historically, this study leads to a moral laxity and the savagery of custom. In this context, it is worth noting that Gómez suggests that obscenity is a motif in Gnostic history: “The Gnostic is susceptible to liturgical profanity, because the sacrum unilaterally contradicts his divinity. | Sacrilegious obscenity is his favourite act. | One of the Gnostic Evangelia is authored by de Sade.”64

Menander, a student of Simon Magus, announces that the world was created by Angels, and enmity reigns between them and Man. Man learns magic from the primordial Absolute65 so as to conquer the Angels, with the aim of achieving redemption. A disciple of Menander was Basilides of Alexandria (second century A.D.). Basilides transplants Syrian gnosis from Antioch to Alexandria. There it merges with the Hebrew Kabbalah and Egyptian wisdom. In the opinion of this Gnostic, within the essence of all can be found the ‘god who isn’t’, and from him emanate numerable Eons. In this science, all emanates from providence: redemption and Evil. The source of all sin is Man’s impulse. Evil,66 and in particular suffering, are substantiated in Man’s previous life. Thus we encounter the concept of pre-existential spiritualism. The soul is capable of recognising and intuitively conceptualising reality.

Isidore of Alexandria, son and disciple of Basilides, is an advocate for amoralism and the total freedom of being. He believes that since redemption is certain, one can do what one pleases, whatever one desires. Gómez thus connects the lawlessness of the Gnostics with the lawlessness of the Revolutionists: “The Gnostic is a born Revolutionary, where the act of an absolute and unreserved rejection is the perfect method through which one announces one’s divine autonomy.”67 According to the Bogotán, the Revolution reached its peak during modernity: “The French Revolution was the highest watermark of the Gnostic tide”68 and “[n]o subsequent Revolution is the result of a new definition of ‘Man’ | All such subsequent Revolutions constitute a reiterated development of the Gnostic definition in changing circumstances.”69 Carpocrates of Alexandria and his son Epiphanes took Isidor’s conceptualisation of immoralism to an extreme. Moreover, they were characterised by their hatred of the Hebrew God. In their vision, Jesus, the natural son of Joseph and Mary, recalled his earlier incarnation and spread hostility aimed at Hebrew laws and customs. Epiphanes claims, that – in the pursuit of redemption – one must sate all manifestations of sensual pleasure and debauchery. Thus Gómez see the anti-Hebraic nature of Gnosticism: “The Gnostic is inevitably anti-Semitic since he must degrade the Creator to the level of the Demiurge.”70

Another famous Gnostic is Valentine, who studied Platonism and the secret wisdom of Egypt in Alexandria, and who attended Isidore’s lectures. He established two schools: the Eastern (Alexandria) and the Italian (Rome). The Eastern School interprets the Book of Genesis and the Evangelia, and develops the theory of the Eons which emanate in primordial pairs (Jesus is here one of the greatest Eons). There is a fundamental difference between the ‘good god’ (the Most High primordial Absolute71) and the Demiurge of the world. Equally, Man is represented dualistically. Within him co-exist two elements: the first, originating from the Evil Demiurge and his Angels (impulses are the bad spirits); the second originate from the ‘good god’. Redemption is necessary. It is made possible through the revelation of Jesus Christ. The Eastern School speaks of three types of Man:

Another famous Gnostic is Valentine, who studied Platonism and the secret wisdom of Egypt in Alexandria, and who attended Isidore’s lectures. He established two schools: the Eastern (Alexandria) and the Italian (Rome). The Eastern School interprets the Book of Genesis and the Evangelia, and develops the theory of the Eons which emanate in primordial pairs (Jesus is here one of the greatest Eons). There is a fundamental difference between the ‘good god’ (the Most High primordial Absolute71) and the Demiurge of the world. Equally, Man is represented dualistically. Within him co-exist two elements: the first, originating from the Evil Demiurge and his Angels (impulses are the bad spirits); the second originate from the ‘good god’. Redemption is necessary. It is made possible through the revelation of Jesus Christ. The Eastern School speaks of three types of Man:

- Hylic, the seat of the Devil;

- Psychic, who have faith but no knowledge (these are capable of choice, to become either Hylic or Pneumatic); and

- Pneumatic, who have attained perfect knowledge (gnosis) and are certain to achieve redemption (redemption comes from their nature).

According to this teaching, Jesus’s corporeal form is only phenomenal [i.e. momentarily apparent] animated by the pneumatic soul, and comes to redeem the Psychic type. The Italian School speaks about the meandering wisdom which begets knowledge, and the Fire which – at the End Times – comes forth from the Earth and consumes all matter, along with the Hylic type. In due course of these considerations, Gómez again warns against pride and recommends faith and scepticism: “Scepticism and Faith solely inoculate against Gnostic Pride. | He who does not believe in God, may gracefully lose his faith in himself.”72 Gómez equally reveals his attitude to theological-philosophical speculation: “Where the sceptic does not smile, his metaphysics dissolve into Gnostic speculation.”73

Cerdo (the Syrian) was another well-known Gnostic of the ancient world. He underlines the dualism of the spirit and matter. He juxdeposes the ‘good god’ (the Father of Jesus Christ, the God of the Evangelia) and the god of justice and cruelty (the God of the Old Testament). Marcion, the son of the Bishop of Sinope, was a student of Cerdo. Excluded from the Church (144 A.D.) for advocating heretical beliefs, he founded a Gnostic church in Rome which existed up until the first half of the fifth century. In the context of the Marconite heresy, one can notice that Gómez takes a position in respect to the relationship of Gnosticism and Christianity:

Gnosticism and Christianity, starting from the same origins, move in opposite directions.

On the basis of a common definition of the human condition, the Christian draws the conclusion that he has been created, the Gnostic, that he is a creator.74

Furthermore:

Christianity and Gnosticism concern themselves with the same subject matter. The feeling of ‘alienation’ was a common experience.

The state of ‘alienation’ is an historical constant, however it becomes more acute in times of social crisis.

‘Alienation’ is the abstract territory, within which either the romantic-Christian or the democratic-Gnostic answers arise.75

The ultimate answers provided by the Christian and Gnostic are radically at odds. The Bogotán provides an emblematic example: “‘Justice’ is a Gnostic concept. | It is sufficient for the fallen deity to assert its proprietary interest. | We Christians ask for mercy.”76

Marcion writes that the Biblical God, the Demiurge, is Evil and is opposed by the ‘good’ God of the Evangelia. This Gnostic advocates a severe puritanism and ascetics. His Docetist doctrine presents the flesh as the repulsive creation of the Demiurge, and rejects His Resurrection. Here, Christ is not prophesised by the Holy Scripture as the Messiah, and the baptism is reserved solely to the unmarried and eunuchs. Many contemporary Gnostic sects hold that Christ is a purely spiritual entity who liberates the soul, which derives from God but is imprisoned by the Evil Demiurge in the sensual world. Although researches consider that anthropological dualism is common to Gnosis and Neoplatonism, Gómez holds that “Gnosticism can be dualist or monist. | Gnosticism is a theory that concerns itself with the nature of the soul.”77 The dominant current of later Gnosticism held that reality is the deed of a free and radically Evil Power.

A particular expression of this idea is the doctrine of Manicheanism, which arose in the third century through the work of Mani of Ctesiphon. In its infancy, it encountered many religious traditions (in Persia, India and China) and later held that it completed the revelations of Zoroaster, Buddha, Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses and Jesus. It speaks of two gods, two great and vying creative powers. Each deed of the Evil divinity is contradicted by a deed of the Good divinity. The conflict will come to an end when the Good divinity vanquishes his Evil opponent. Thus, Gnosticism – equally as the religion of democracy – is a relevant phenomenon.

IV

The following are representative of contemporary Gnosticism: New Age, National Socialism, Marxism Leninism and the Psychoanalysis of Jung.78 These fanatical and anti-Christian currents are concerned with the liberation of Man by Man. The author of the Scholia writes that “the Gnostic soteriology ferments in the multiplicity of all modern sects.”79 Moreover, he directs our attention to another aspect of contemporary Gnosticism, i.e. to contradict the lessons of Original Sin: “The dogma of Man’s natural goodness is expressed with the assistance of ethical terminology that is central to the experience of the Gnostic. | Man is naturally good because he is naturally divine.”80

Given the history and characteristics of Gnosticism, let us recall what Nicolás Gómez Dávila has to say about democracy in his Scholia to an Implicit Text. Namely, he determines that democracy is not only a political fact, but also a religion. It is a religion in which Man takes the place of God. The thinker describes this as a “metaphysical perversion”81 and highlights its Gnostic and Satanic background. In the opinion of the Author of the Scholia, contemporary Man behaves as if he were sovereign and as if he alone were capable of deciding questions of Good and Evil, Truth and Falsity, Beauty and Ugliness. A consequence of this worldview and attitude is that the modern world is a spectacle of iniquity.

To Gómez Dávila, democracy is an “Empire of lies”82 in which the masses are hypnotised by pro-liberal propaganda, while terror and slavery reign. The main vehicle of despotic governance is the rule of positivist law83 and a bureaucracy which rapidly becomes its own objective. Bureaucracy oppresses, and its excess are naturally repellent.84 The resulting falsity and disgust felt towards democracy among those who are so repelled is particularly apparent during elections, when democrats commit the most egregious frauds to flatter the masses. This leads to a situation where the masses are bribed with the “promise of another’s property”85 as well as selling one’s self “to the wealthy, for cash | to the poor, in installments.”86 Democratic politicians are ultimately simple frauds who “benefit from their robbery.”87 Thus the thinker believes that “among those popularly elected, those worthy of respect are only the imbeciles – the intelligent man, on the other hand, to be elected, must lie.”88 Moreover, “[w]here those popularly elected do not belong to the lowest intellectual, moral and social class, we can be certain that anti-democratic forces interfered with the natural progress of the democratic process.”89 As a consequence, Dávila further adds that “[i]n a democracy, the ‘Man of principle’ is worth barely a little more [i.e. than the democratic Man].”90

Generally, Gómez Dávila considers politics – as a typically democratic activity – as a “necessary Evil” and “a subordinate activity.”91 In the eyes of the Bogotán Recluse, democracy principally demoralises Man. Not just because of the persistent and enduring culture of falsehood, but also due to the inevitable temporariness of all laws, regulations and political arrangements. Thus, only the unscrupulous are capable of reaching the heights of democratic society, which in turn deepens the corruption of the masses.

The immediately obvious reason for this is because the ruling elite of a democracy cannot pass any reform without guaranteeing their electoral support. Meanwhile, a majority of the electors are unable to truly appreciate the issues on which they are to decide, either directly or indirectly. These characteristic contradictions of the democratic process and democratic man precipitate numerous crises: “the more serious the problem, the greater the number of incompetents who democracy calls upon to provide solutions.”92 Moreover, Gómez Dávila notes that in a democracy there are numerous matters which it is not permitted to raise in public: “race, social illness, the climate of the times, all appear to be corrosive substances [to the democratic status quo].”93 For example, equality is incessantly discussed among the demos. However, the author of the Scholia holds that “people are less equal than they say, but more than they think,” and “if people were to be born equal, they would invent inequality to kill the boredom.”94 He adds that “hierarchy is heavenly”95 and the truly equal are only those condemned to hell.

It is therefore unsurprising that Nicolás Gómez Dávila considers the word “democrat” to be a uniquely pejorative epithet: “the uplift that is felt before Greek literature and art obscures [i.e for future generations] the true nature of Greek Man: jealous, traitorous, sportsman, democrat and deviant.”96 The Columbian, whose work shows him to be the friend of genuine diversity and plurality, cannot in any way accept the presence of the democrat [i.e. due to the democrat’s levelling tendency]. Thus, he arrives to the conclusion that the “height of reactionary wisdom would depend on finding a place even for the democrat.”97

If we realise that the Columbian philosopher is above all the implacable enemy of a progress which is typical for the democrat, as well as his idolatrous worship of science and technology, then it becomes clear that his only response to the modern era is total isolation and solitude. Gómez Dávila is aware of the consequences of these beliefs, and is ready to face them. To him, this is the price of independence and integrity.98 He writes: “The struggle against the modern world must be carried out in solitude. | Where there are two, there is treachery.”99

– Krzysztof Urbanek is a scholar of the work of Nicolás Gómez Dávila and has dedicated his career to translating the work of the Colombian reactionary thinker from Spanish into Polish. His latest work is the 1054 page volume Scholia do Tekstu Implicite (Warsaw: Furta Sacra, 2014).

Endnotes:

[This is a translation from a draft of the original Polish unpublished manuscript by Dr. Krzysztof Urbanek of Furta Sacra publishing, dated 14 April 2016. The translator’s editorial comments are contained within parentheses in the body of the text and footnotes that follow.]

- [Throughout this article, Dr. Urbanek will refer to Nicolás Gómez Dávila as the “Author” (of the cited works) or as the “Bogotán” or “Bogotán Recluse” (Dávila being a native of Bogotá, Columbia), the “Thinker”, “Catholic Thinker” or “Philosopher”. These are used interchangeably. N.b., Dávila also referred to himself as “Don Colacho”.]

- Nicolás Gómez Dávila, Escolios a un Texto Implícito (Bogotá: Villegas Editores, 2005).

- Revista del Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario, Vol 81 No. 542 (April June 1988).

- The writer relies on the Spanish language edition of the work: Nicolás Gómez Dávila, Textos (Barcelona: Atalanta, 2010 [Bogotá: Editorial Voluntad, 1959]) pp. 55−84.

- Nicolás Gómez Dávila, Scholia do Tekstu Implicite, Krzysztof Urbanek (trans.) (Warsaw: Furta Sacra, 2014) p. 105. [Dr. Urbanek’s original text, which is his translation from the Spanish, reads “Każdy pisarz komentuje w nieskończoność swój krótki tekst pierwotny”. The Spanish original was not available to the translator. For the most recent publication of Dávila’s work in English, Anglophone readers are directed to the bilingual edition of his selected aphorisms: Nicolás Gómez Dávila, Scholia to an Implicit Text (Bogotá: Villegas Editores, 2013). An online archive of English translations of Dávila’s work is located at the “Don Cloacho’s Aphorisms webpage”, <don-colacho.blogspot.com> (accessed 30 April 2016).]

- Dávila, Textos, op. cit. p. 59.

- [i.e. that communism best exemplifies the religious nature of democratic ideology.]

- Dávila, Textos, op. cit. p. 60.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. p. 61.

- Ibid. p. 62.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. p. 62-63.

- Ibid. p. 63.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. p. 64.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. p. 69.

- Ibid. p. 71.

- Ibid. p. 72.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. p. 73.

- Ibid. p. 74.

- Ibid. p. 75.

- Ibid. p. 76.

- Ibid. p. 77.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. p. 78.

- Ibid. p. 79.

- Ibid. p. 80.

- Ibid. p. 81.

- [This is an interpretive translation of Dr. Urbanek’s phraseology. The original text reads: “Burżuazja zaś świadomie wybiera państwo laickie, aby nie musieć konfrontować „swoich kombinacji” z „wtrętami aksjologicznymi”.” The phrase “swoich kombinacji” is taken to mean the mendacity and craftiness of modern Man’s subjective whims, and the “wtrętami aksjologicznymi” is literally translated as an “interfering axiology”. The distinction being drawn by Dr. Urbanek between the two terms is greater than the mere opposition between the subjective and the objective; what is being described is the inversion of the Divine (or natural) order.]

- Dávila, Textos, op. cit. p. 81.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. p. 82.

- Ibid. p. 83.

- [This is an interpretative translation of Dr. Urbanek’s text. The original words are: “Gómez pisze o znudzeniu i okrucieństwie człowieka, naśladującego wszechmoc Boga.” A literal translation may suggest that the boredom and cruelty of Man is a result of Man’s imitation of God; however, a clearer translation requires the interpolation, into the original text, that the boredom and cruelty is a function of the failed imitation, and furthermore, that any imitation of God is an exercise doomed to failure. Thus, all attempts to deify Man will deaden the individual spirit and dehumanise society. Taken in its context, this is understood to be the intended meaning of Dr. Urbanek’s original text.]

- [Here, the total reactionary rebellion – “totalna reakcyjna rebelia” – is the radical rejection of, and departure from, the deification of Man, or in other words, the return to a transcendent and hierarchical paradigm (social, moral and individual) which is antithetical to the demotic ideologies of the eighteenth through to the twentieth centuries. For more on this, see: “Transcendence and the Aristocratic Principle: ‘Throne and Altar’ as Essential Criteria for Civilisation and National Particularism; Defence Against Demotic Tyranny” in Aristokratia III (2015)]

- There is only one direct critique of Gnosticism in the two considerable volumes of the Scholia to an Implicit Text. See further: Nicolás Gómez Dávila, Scholia, Urbanek (trans.) op. cit. pp. 305-306.

- Ibid. p. 819.

- Ibid. p. 914.

- “Decidedly, Stoicism is the cradle of all error | (Deification of Man, determinism, natural law, egalitarianism, cosmopolitanism, etc. etc.)” (Ibid. p. 402).

- Dávila, Scholia, Urbanek (trans.) op. cit. p. 770.

- [This is an interpretive translation of Prof. Urbanek’s original text, which reads “Gnostycyzm mówi o identyczności poznającego, czyli gnostyka, poznawanego, czyli boskiej substancji, i środka poznania, czyli gnozy.” The word “identyczności” may be literally interpreted as “identicality” however “consubstantial” is used for the sake of grammatical clarity. The translator understands this passage to convey the notion that the relationship between the three concepts – the Gnostic, the divine essence and gnosis itself – is to be interpreted in an almost Trinitarian manner. The text that follows is of an elucidatory nature and its translation does not raise any caveats.]

- [i.e. when the animating intention to seek and achieve awareness comes from within the individual seeking gnostic redemption.]

- Dávila, Scholia, Urbanek (trans.) op. cit. p. 769.

- Ibid. p. 776.

- Ibid. p. 739.

- “Savior-saved” [likewise, Dr. Urbanek’s translation in his original Polish text is “zbawiający-zbawiany.”]

- Dávila, Scholia, Urbanek (trans.) op. cit. p. 774.

- [Dr. Urbanek uses the word “ideowym” which may readily be translated as “ideological”, however, the term “philosophical” is better suited for the English translation in the context of a reactionary critique of modernity.]

- Dávila, Scholia, Urbanek (trans.) op. cit. p. 775.

- Ibid. p. 1051.

- Ibid. p. 735.

- Ibid. p. 817.

- Ibid. p. 819.

- Ibid. p. 818.

- Thus, one may locate the historical basis for an interpretation of the following text of the Scholia: “Modern Man always discovers his soul in a filthy place – such as the paradigmatic brothel in Tyre” (Ibid. p. 775).

- Dávila, Scholia, Urbanek (trans.) op. cit. p. 770.

- [Dr. Urbanek’s original text is “Jednia” or “Oneness.”]

- Meanwhile, it seems that Gómez has failed to notice the Gnostic interest in Evil, when he writes: “The Gnostic does not ask as per Tertullian: Undem alum? but: Unde Ego?” (I am here, I am faultless) [Prof. Urbanek’s Polish translation reads: “Ja tutaj! Ja doskonały!”] (Dávila, Scholia, Urbanek (trans.) op. cit. p. 818).

- Dávila, Scholia, Urbanek (trans.) op. cit. p. 770.

- Ibid. p. 773.

- Ibid. p. 790.

- Ibid. p. 913.

- [Dr. Urbanek’s original words read: “prajednia najwyższa” which can be literally translated as the “primordial oneness that is most high.” Here, the treatment of the original text complies with the earlier translation at n 65 supra, adjusted for grammatical clarity.]

- Dávila, Scholia, Urbanek (trans.) op. cit. p. 776. [Prof. Urbanek’s original words, in the last line, read: “Kto nie wierzy w Boga, może zdobyć się na tyle przyzwoitości, by nie wierzyć w siebie.”]

- Dávila, Scholia, Urbanek (trans.) op. cit. p. 701. [The term “smile” here is understood to indicate a disposition of the spirit which is akin to a gracious and humble scepticism, being self-aware of one’s limitations, a sincere and honest ability to approach that which is doubtful or not readily understood, not allowing one’s self to be carried by a wounded ego, a certain levity of heart which reflects and informs one’s intellect and moral attitude.]

- Dávila, Scholia, Urbanek (trans.) op. cit. p. 769.

- Ibid. p. 773.

- Ibid. p. 774.

- Ibid. p. 819. See Gómez further: “The core of Pelagianism is the Gnostic definition of the soul” (Ibid. p. 818).

- See further: Witold Myszor (ed.) Gnostycyzm Antyczny i Współczesna Neognoza [“The Gnosticism of Antiquity and Contemporary Neognosticism”] (Warsaw: Akademię Teologii Katolickiej, 1996). [This work is unavailable in English translation.]

- Dávila, Scholia, Urbanek (trans.) op. cit. p. 648.

- Ibid. p. 818.

- Ibid. p. 587.

- Ibid. p. 315.

- [Dr. Urbanek’s original words read: “władza sądownicza” which literally translates as the “rule” – in a negative sense, as in the tyranny – of the judicial class or law courts.]

- Dávila, Scholia, Urbanek (trans.) op. cit. p. 480.

- Ibid. p. 126.

- Ibid. p. 621.

- Ibid. p. 985.

- Ibid. p. 974.

- Ibid. p. 978.

- Ibid. p. 893.

- Ibid. p. 409.

- Ibid. p. 39.

- Ibid. p. 638.

- Ibid. p. 516.

- Ibid. p. 564.

- Ibid. p. 1033.

- Ibid. p. 683. [Emphasis added by the translator. This is interpreted as an expression of Dávila’s Catholic charity and sense of inclusivity, that he would express a desire to locate a place even for the sacrilegious element.]

- [Dr. Urbanek’s original word is “bezkompromizowności” which translates literally as the state of no compromise on principal. Here it is translated for the sake of brevity as “integrity.”]

- Dávila, Scholia, Urbanek (trans.) op. cit. p. 482.

Citation Style:

This article is to be cited according to the following convention:

Krzysztof Urbanek, “Adversus Haereses: Nicolás Gómez Dávila Against the Religion of Democracy” Edwin Dyga (translator) SydneyTrads – Weblog of the Sydney Traditionalist Forum (30 April 2016) <sydneytrads.com/2016/04/30/2016-symposium-krzysztof-urbanek> (accessed [date]).

Almost all of Gómez Dávila’s writings are collections of aphorisms called — in Spanish — Escolios. Escolios comes from the Greek scholión, which literally means commentary. This term was used in old manuscripts for commentaries made between the lines by someone other than the original author of the text. These escolios have been compiled into his main works: Escolios a un Texto Implícito I, Escolios a un Texto Implícito II, Nuevos Escolios a un Texto Implícito I, Nuevos Escolios a un Texto Implícito II, and Sucesivos Escolios a un Texto Implícito.

Almost all of Gómez Dávila’s writings are collections of aphorisms called — in Spanish — Escolios. Escolios comes from the Greek scholión, which literally means commentary. This term was used in old manuscripts for commentaries made between the lines by someone other than the original author of the text. These escolios have been compiled into his main works: Escolios a un Texto Implícito I, Escolios a un Texto Implícito II, Nuevos Escolios a un Texto Implícito I, Nuevos Escolios a un Texto Implícito II, and Sucesivos Escolios a un Texto Implícito. Nicolás Gómez Dávila, being a devout Catholic, was also highly critical of modern atheism by affirming that “todo fin diferente de Dios nos deshonra”[12]: “every goal different from God dishonors us” and that we must “Creer en Dios, confiar en Cristo”[13]: “Believe in God, trust in Christ.” This spiritual aspect of life is what provides an adequate interpretation of it: “si no heredamos una tradicion espiritual que la interprete, la experiencia de la vida nada enseña”[14]: “if we do not inherit a spiritual tradition which interprets it, life experience teaches nothing.”

Nicolás Gómez Dávila, being a devout Catholic, was also highly critical of modern atheism by affirming that “todo fin diferente de Dios nos deshonra”[12]: “every goal different from God dishonors us” and that we must “Creer en Dios, confiar en Cristo”[13]: “Believe in God, trust in Christ.” This spiritual aspect of life is what provides an adequate interpretation of it: “si no heredamos una tradicion espiritual que la interprete, la experiencia de la vida nada enseña”[14]: “if we do not inherit a spiritual tradition which interprets it, life experience teaches nothing.”

Pourtant, en lisant Gómez Dávila, on sent une note discordante, quelque chose qui ne va pas tout à fait. Une indifférence ostentatoire à la politique, une retraite olympienne des bas-fonds de l'histoire, voilà ce qui dérange, du moins pour l'écrivain. C'est une attitude légitime, bien sûr, mais qui finit par rendre une pensée trop exsangue et sans vie, trop dérangeante et abstraite. Bien sûr, le Colombien n'est pas comparable, en termes de courage intellectuel, à l'insupportable et inoffensif Cioran, mais il est révélateur que, comme le Roumain ou, par exemple, Guénon, il fasse partie du catalogue Adelphi, une maison d'édition qui, sans préjudice de ses énormes mérites, a toujours regardé la politique et l'histoire avec agacement, sinon avec hauteur, avec snobisme. Un regard au-dessus de la mêlée, un refus souverain du choc, de ce conflit qui est la chair de la politique, que l'on ne peut partager, surtout pour ceux qui se reconnaissent dans l'héritage d'un Machiavel ou d'un Leopardi.

Pourtant, en lisant Gómez Dávila, on sent une note discordante, quelque chose qui ne va pas tout à fait. Une indifférence ostentatoire à la politique, une retraite olympienne des bas-fonds de l'histoire, voilà ce qui dérange, du moins pour l'écrivain. C'est une attitude légitime, bien sûr, mais qui finit par rendre une pensée trop exsangue et sans vie, trop dérangeante et abstraite. Bien sûr, le Colombien n'est pas comparable, en termes de courage intellectuel, à l'insupportable et inoffensif Cioran, mais il est révélateur que, comme le Roumain ou, par exemple, Guénon, il fasse partie du catalogue Adelphi, une maison d'édition qui, sans préjudice de ses énormes mérites, a toujours regardé la politique et l'histoire avec agacement, sinon avec hauteur, avec snobisme. Un regard au-dessus de la mêlée, un refus souverain du choc, de ce conflit qui est la chair de la politique, que l'on ne peut partager, surtout pour ceux qui se reconnaissent dans l'héritage d'un Machiavel ou d'un Leopardi.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

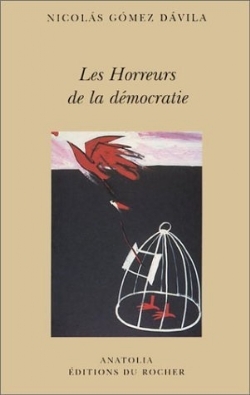

Digg

Digg

Nicolas Gomez Davila est de ces rares auteurs qui tiennent leur lecteur en assez haute estime pour ne lui offrir que le meilleur d’eux-mêmes. Le véritable titre de ces formes brèves, qui ne sont ni des aphorismes, ni des sentences, rassemblées sous le titre Les Horreurs de la Démocratie (choix d’éditeur non dépourvu de roborative provocation) est « Escolios a un texto implicito », Scolies pour un texte implicite. Ces « scolies » ont pour règle de ne laisser apercevoir de la pensée que la fine pointe et pour vertu, la générosité de supposer au lecteur l’intelligence et l’art de déployer, à partir de ces fines pointes, un texte qui est à la fois absent et présent, implicite, c’est à dire donné, sans être pour autant révélé.

Nicolas Gomez Davila est de ces rares auteurs qui tiennent leur lecteur en assez haute estime pour ne lui offrir que le meilleur d’eux-mêmes. Le véritable titre de ces formes brèves, qui ne sont ni des aphorismes, ni des sentences, rassemblées sous le titre Les Horreurs de la Démocratie (choix d’éditeur non dépourvu de roborative provocation) est « Escolios a un texto implicito », Scolies pour un texte implicite. Ces « scolies » ont pour règle de ne laisser apercevoir de la pensée que la fine pointe et pour vertu, la générosité de supposer au lecteur l’intelligence et l’art de déployer, à partir de ces fines pointes, un texte qui est à la fois absent et présent, implicite, c’est à dire donné, sans être pour autant révélé.  Les Scolies de Gomez Davila sont une œuvre de combat. Ce qui est en jeu n’est rien moins que la dignité et la liberté humaines, mais à la différence de tant d’autres qui mâchonnent les mots de « dignité » et de « liberté », Gomez Davila ne pactise point avec les forces qui les galvaudent et les ruinent. Ne nous attardons pas sur les roquets-folliculaires qui furent lancés aux basques de ce livre magnifique : ils n’existent que pour en illustrer la pertinence : « Le démocrate ne considère pas que les gens qui le critiquent se trompent, mais qu’ils blasphèment ». Cette figure du Moderne, que Gomez Davila nomme le « démocrate » (non, précise-t-il en tant que partisan d’un système politique mais comme défenseur d’une « perversion métaphysique ») peut, en effet, être définie ici comme fondamentaliste dans la mesure où elle ne louange le « débat », la « discussion », le « polémos » que sous l’impérative condition que ceux avec qui il est permis de débattre, discuter et polémiquer fussent déjà, de longtemps et notoirement, du même avis qu’elle ; et qu’ils le soient, par surcroît, avec le même vocabulaire, les mêmes rhétoriques, et si possible, avec les mêmes intonations, le même style ou, plus probablement, la même absence de style. Le démocrate fondamentaliste ne « raisonne » ainsi que dans les limites de sa folie procustéenne ; son amour de l’humanité « en général » ne s’accomplit qu’au mépris du particulier ; la liberté d’expression ne lui vaut que strictement réservée à ceux qui n’ont rien à dire ; la « dignité » humaine ne mérite à ses yeux d’être défendue qu’en faveur de ceux qui s’en moquent et s’avilissent à plaisir.

Les Scolies de Gomez Davila sont une œuvre de combat. Ce qui est en jeu n’est rien moins que la dignité et la liberté humaines, mais à la différence de tant d’autres qui mâchonnent les mots de « dignité » et de « liberté », Gomez Davila ne pactise point avec les forces qui les galvaudent et les ruinent. Ne nous attardons pas sur les roquets-folliculaires qui furent lancés aux basques de ce livre magnifique : ils n’existent que pour en illustrer la pertinence : « Le démocrate ne considère pas que les gens qui le critiquent se trompent, mais qu’ils blasphèment ». Cette figure du Moderne, que Gomez Davila nomme le « démocrate » (non, précise-t-il en tant que partisan d’un système politique mais comme défenseur d’une « perversion métaphysique ») peut, en effet, être définie ici comme fondamentaliste dans la mesure où elle ne louange le « débat », la « discussion », le « polémos » que sous l’impérative condition que ceux avec qui il est permis de débattre, discuter et polémiquer fussent déjà, de longtemps et notoirement, du même avis qu’elle ; et qu’ils le soient, par surcroît, avec le même vocabulaire, les mêmes rhétoriques, et si possible, avec les mêmes intonations, le même style ou, plus probablement, la même absence de style. Le démocrate fondamentaliste ne « raisonne » ainsi que dans les limites de sa folie procustéenne ; son amour de l’humanité « en général » ne s’accomplit qu’au mépris du particulier ; la liberté d’expression ne lui vaut que strictement réservée à ceux qui n’ont rien à dire ; la « dignité » humaine ne mérite à ses yeux d’être défendue qu’en faveur de ceux qui s’en moquent et s’avilissent à plaisir.  La composition pointilliste des Scolies, qui mêlent les aperçus éthiques, esthétiques et politiques, interdit que l’on traitât de chaque domaine comme d’une région séparée. Le bien, le beau et le vrai sont indissociables. L’esthète est toujours moraliste et politique. « Le monde moderne est un soulèvement contre Platon ». Il appartient donc au « réactionnaire » tel que le définit Gomez Davila (dont la vocation est d’être « l’asile de toutes les idées frappées d’ostracisme par l’ignominie moderne ») d’œuvrer à la recouvrance du platonisme, non en tant que système philosophique ( à supposer qu’il existât un « système » platonicien hors des aides-mémoires de quelques pédagogues trop pressés d’enseigner ce qu’ils ne savent pas pour lire des Dialogues) mais en tant qu’expérience métaphysique fondamentale de la lecture (lecture du monde non moins que lecture des livres). « Derrière chaque vocable se lève le même vocable avec une majuscule : derrière l’amour, l’Amour, derrière la rencontre la Rencontre. L’univers s’évade de sa prison lorsque dans l’instance individuelle, nous percevons l’essence. »

La composition pointilliste des Scolies, qui mêlent les aperçus éthiques, esthétiques et politiques, interdit que l’on traitât de chaque domaine comme d’une région séparée. Le bien, le beau et le vrai sont indissociables. L’esthète est toujours moraliste et politique. « Le monde moderne est un soulèvement contre Platon ». Il appartient donc au « réactionnaire » tel que le définit Gomez Davila (dont la vocation est d’être « l’asile de toutes les idées frappées d’ostracisme par l’ignominie moderne ») d’œuvrer à la recouvrance du platonisme, non en tant que système philosophique ( à supposer qu’il existât un « système » platonicien hors des aides-mémoires de quelques pédagogues trop pressés d’enseigner ce qu’ils ne savent pas pour lire des Dialogues) mais en tant qu’expérience métaphysique fondamentale de la lecture (lecture du monde non moins que lecture des livres). « Derrière chaque vocable se lève le même vocable avec une majuscule : derrière l’amour, l’Amour, derrière la rencontre la Rencontre. L’univers s’évade de sa prison lorsque dans l’instance individuelle, nous percevons l’essence. » Si pour Gomez Davila la politique est impossible, c’est une raison supplémentaire pour s’y intéresser, mais seul. « La lutte contre le monde moderne doit être conduite dans la solitude. Lorsqu’on est deux, il y a déjà trahison ». On songe ici à la phrase de Montherlant : « Dès que les hommes se rassemblent, ils travaillent pour quelque erreur. » Il n’en demeure pas moins qu’il y eut des temps où l’ordre politique semblait destiné à nous éviter le pire, autant que possible. Le pire, c’est à-dire, le nihilisme, le totalitarisme, la terreur. « La démocratie a la terreur pour moyen et le totalitarisme pour fin ». Toutefois, le « totalitarisme » et la « terreur » ne disent point l’entièreté du pire. Le démocrate ne cesse d’en parler, de s’en prétendre le rempart lorsqu’il s’en trouve être la condition, la prémisse. Le pire est ce que l’homme devient, ce que tous les hommes deviennent, lorsque la contemplation disparaît du monde, lorsque le commerce entre les hommes ne s’ordonne plus qu’à l’économie. « L’absence de vie contemplative fait de la vie active d’une société un grouillement de rats pestilentiels ». Ce par quoi le langage témoigne de la contemplation, et de cette joie profonde, ambrée et lumineuse du Logos-Roi, c’est peu dire que le Moderne ne veut plus en entendre parler. Son monde, il le veut sans faille, compact et massif, c’est-à-dire réduit à lui-même, à sa pure immanence, autrement dit à l’opinion que les plus sots et les plus irréfléchis se font de lui. « Le moderne se refuse à entendre le réactionnaire, non que ses objections lui paraissent irrecevables, mais parce qu’elles ne lui sont pas intelligibles ».

Si pour Gomez Davila la politique est impossible, c’est une raison supplémentaire pour s’y intéresser, mais seul. « La lutte contre le monde moderne doit être conduite dans la solitude. Lorsqu’on est deux, il y a déjà trahison ». On songe ici à la phrase de Montherlant : « Dès que les hommes se rassemblent, ils travaillent pour quelque erreur. » Il n’en demeure pas moins qu’il y eut des temps où l’ordre politique semblait destiné à nous éviter le pire, autant que possible. Le pire, c’est à-dire, le nihilisme, le totalitarisme, la terreur. « La démocratie a la terreur pour moyen et le totalitarisme pour fin ». Toutefois, le « totalitarisme » et la « terreur » ne disent point l’entièreté du pire. Le démocrate ne cesse d’en parler, de s’en prétendre le rempart lorsqu’il s’en trouve être la condition, la prémisse. Le pire est ce que l’homme devient, ce que tous les hommes deviennent, lorsque la contemplation disparaît du monde, lorsque le commerce entre les hommes ne s’ordonne plus qu’à l’économie. « L’absence de vie contemplative fait de la vie active d’une société un grouillement de rats pestilentiels ». Ce par quoi le langage témoigne de la contemplation, et de cette joie profonde, ambrée et lumineuse du Logos-Roi, c’est peu dire que le Moderne ne veut plus en entendre parler. Son monde, il le veut sans faille, compact et massif, c’est-à-dire réduit à lui-même, à sa pure immanence, autrement dit à l’opinion que les plus sots et les plus irréfléchis se font de lui. « Le moderne se refuse à entendre le réactionnaire, non que ses objections lui paraissent irrecevables, mais parce qu’elles ne lui sont pas intelligibles ».

Ces Scolies à un texte implicite, se donnent à lire ainsi, non seulement comme une suite d’aperçus lucides en forme d’exercices de désabusement, dans la lignée des meilleurs d’entre nos Moralistes, tels que Vauvenargues ou Rivarol, mais aussi, comme un Art de la guerre, un traité de combat contre les « lapalicistes ». « Est démocrate, celui qui attend du monde extérieur la définition de ses objectifs ». Contre la passivité des tautologies et contre le règne de la quantité qu’elle instaure, c’est à la seule vie intérieure, à la seule âme imprescriptible du lecteur qu’il appartient, dans cette solitude essentielle qui est la véritable communion, de nuancer d’un imprévisible ensoleillement, autrement dit, d’une espérance implicite mais prête à bondir dans le monde, ces Scolies qu’un inattentif regard ordonnerait au seul pessimisme. D’autant plus inquiétantes, roboratives et salubres, ces Scolies, que ce qu’elles ne disent pas chemine en nous à l’insu des censeurs ! « Seuls conspirent efficacement contre le monde actuel ceux qui propagent en secret l’admiration de la beauté. »

Ces Scolies à un texte implicite, se donnent à lire ainsi, non seulement comme une suite d’aperçus lucides en forme d’exercices de désabusement, dans la lignée des meilleurs d’entre nos Moralistes, tels que Vauvenargues ou Rivarol, mais aussi, comme un Art de la guerre, un traité de combat contre les « lapalicistes ». « Est démocrate, celui qui attend du monde extérieur la définition de ses objectifs ». Contre la passivité des tautologies et contre le règne de la quantité qu’elle instaure, c’est à la seule vie intérieure, à la seule âme imprescriptible du lecteur qu’il appartient, dans cette solitude essentielle qui est la véritable communion, de nuancer d’un imprévisible ensoleillement, autrement dit, d’une espérance implicite mais prête à bondir dans le monde, ces Scolies qu’un inattentif regard ordonnerait au seul pessimisme. D’autant plus inquiétantes, roboratives et salubres, ces Scolies, que ce qu’elles ne disent pas chemine en nous à l’insu des censeurs ! « Seuls conspirent efficacement contre le monde actuel ceux qui propagent en secret l’admiration de la beauté. »

Le monde, disent les Théologiens médiévaux, est « la grammaire de Dieu ». C’est ainsi que nous perdons ou gagnons en même temps Dieu et le monde, de même que nous perdons en même temps (ou gagnons) la compréhension d’Homère et des Evangiles. « Lorsque le bon goût et l’intelligence vont de pair, la prose ne semble pas écrite par l’auteur, mais par elle-même. » Que nous dit le texte implicite sinon notre propre secret qui est le secret du monde ? Tout se joue alors dans la voix, la voix unique, irremplaçable, celle de l’amour divin ( « Nous ne sommes irremplaçables que pour Dieu ») ; la plus irrécusable preuve de l’Un étant que toute chose, tant que demeurent les droits imprescriptibles de l’âme, est unique. Point de feuille dont les nervures fussent exactement semblables à sa voisine. Le grand mythe moderne, au sens de mensonge, tient dans cette lâcheté, cette paresse face à l’interprétation qui sans fin hiérarchise les êtres et les choses du plus épais jusqu’au plus subtil. Le Moderne veut croire à tout prix que le monde est inintelligible pour pouvoir le saccager à sa guise. Le bonheur et le malheur est qu’il en est rien. Tout est écrit, et nous ne faisons qu’ajouter la ponctuation. « Mes phrases concises sont les touches d’une composition pointilliste ». L’implicite ne serait alors que le non-encore ponctué. « Si l’univers est d’une lecture malaisée, ce n’est pas qu’il soit un texte hermétique, mais parce que c’est un texte sans ponctuation. Sans l’intonation adéquate, montante ou descendante, sa syntaxe ontologique est inintelligible. »

Le monde, disent les Théologiens médiévaux, est « la grammaire de Dieu ». C’est ainsi que nous perdons ou gagnons en même temps Dieu et le monde, de même que nous perdons en même temps (ou gagnons) la compréhension d’Homère et des Evangiles. « Lorsque le bon goût et l’intelligence vont de pair, la prose ne semble pas écrite par l’auteur, mais par elle-même. » Que nous dit le texte implicite sinon notre propre secret qui est le secret du monde ? Tout se joue alors dans la voix, la voix unique, irremplaçable, celle de l’amour divin ( « Nous ne sommes irremplaçables que pour Dieu ») ; la plus irrécusable preuve de l’Un étant que toute chose, tant que demeurent les droits imprescriptibles de l’âme, est unique. Point de feuille dont les nervures fussent exactement semblables à sa voisine. Le grand mythe moderne, au sens de mensonge, tient dans cette lâcheté, cette paresse face à l’interprétation qui sans fin hiérarchise les êtres et les choses du plus épais jusqu’au plus subtil. Le Moderne veut croire à tout prix que le monde est inintelligible pour pouvoir le saccager à sa guise. Le bonheur et le malheur est qu’il en est rien. Tout est écrit, et nous ne faisons qu’ajouter la ponctuation. « Mes phrases concises sont les touches d’une composition pointilliste ». L’implicite ne serait alors que le non-encore ponctué. « Si l’univers est d’une lecture malaisée, ce n’est pas qu’il soit un texte hermétique, mais parce que c’est un texte sans ponctuation. Sans l’intonation adéquate, montante ou descendante, sa syntaxe ontologique est inintelligible. » « Je ne suis pas un intellectuel moderne contestataire mais un paysan médiéval indigné ». Si le mot rebelle voulait encore dire quelque chose, l’exégète des Scolies pourrait en faire usage ; tel n’est pas le cas. Demeure à travers ce qui est dit la possibilité offerte de n’être pas soumis au temps, d’imaginer ou de se souvenir d’une cohérence du monde, mystérieuse et sensible à « l’intonation montante ou descendante ». L’implicite des Scolies est une mise-en-demeure à la recouvrance de l’histoire sacrée, c’est-à-dire d’une histoire qui ne se réduit pas à « l’incertitude de l’anecdote » ni à la « futilité des chiffres ». En ce sens, « les ennemis du mythe ne sont pas les amis de la réalité mais de la banalité », le mythe n’étant pas alors le mensonge, mais bien la réverbération du vrai, la beauté suspendue entre l’immanence ingénue de notre race et la transcendance universelle. Tout écrivain digne de ce nom récite une mythologie d’autant plus réelle, au sens platonicien, c’est-à-dire d’autant plus vraie, qu’elle lui est plus personnelle, se proposant à lui presque par inadvertance, comme une fatalité heureuse. « Les penseurs contemporains sont aussi différents les uns des autres que les hôtels internationaux dont la structure uniforme se pare superficiellement de motifs indigènes. Alors qu’en vérité seul est intéressant le particularisme qui s’exprime dans un langage cosmopolite. »

« Je ne suis pas un intellectuel moderne contestataire mais un paysan médiéval indigné ». Si le mot rebelle voulait encore dire quelque chose, l’exégète des Scolies pourrait en faire usage ; tel n’est pas le cas. Demeure à travers ce qui est dit la possibilité offerte de n’être pas soumis au temps, d’imaginer ou de se souvenir d’une cohérence du monde, mystérieuse et sensible à « l’intonation montante ou descendante ». L’implicite des Scolies est une mise-en-demeure à la recouvrance de l’histoire sacrée, c’est-à-dire d’une histoire qui ne se réduit pas à « l’incertitude de l’anecdote » ni à la « futilité des chiffres ». En ce sens, « les ennemis du mythe ne sont pas les amis de la réalité mais de la banalité », le mythe n’étant pas alors le mensonge, mais bien la réverbération du vrai, la beauté suspendue entre l’immanence ingénue de notre race et la transcendance universelle. Tout écrivain digne de ce nom récite une mythologie d’autant plus réelle, au sens platonicien, c’est-à-dire d’autant plus vraie, qu’elle lui est plus personnelle, se proposant à lui presque par inadvertance, comme une fatalité heureuse. « Les penseurs contemporains sont aussi différents les uns des autres que les hôtels internationaux dont la structure uniforme se pare superficiellement de motifs indigènes. Alors qu’en vérité seul est intéressant le particularisme qui s’exprime dans un langage cosmopolite. »

Meanwhile for the liberal, the reason that the radical displays its creation of the human will which aspire for absolute freedom.

Meanwhile for the liberal, the reason that the radical displays its creation of the human will which aspire for absolute freedom.

The subject of Nicolás Gómez Dávila’s Text Implicite is democracy. According to the Author, democracy is a new religion; more precisely, an anthropotheistic religion in which Man is presented as God. The Catholic Thinker therefore concludes that the ultimate consequence can only be to treat democracy as if it were a form of Satanism.

The subject of Nicolás Gómez Dávila’s Text Implicite is democracy. According to the Author, democracy is a new religion; more precisely, an anthropotheistic religion in which Man is presented as God. The Catholic Thinker therefore concludes that the ultimate consequence can only be to treat democracy as if it were a form of Satanism. According to Nicolás Gómez Dávila, the sovereign Will reigns in liberal and individualistic democracies, while the authentic Will reigns in collective and despotic democracies. In his characterisation of the democratic religion, the Author of the Scholia holds that “the transformation of a liberal and individualistic democracy, into a collective and despotic democracy, does not molest the democratic intention, nor does it depart from its promised objectives.”23 This is because the law of the democratic Will has the mandate to coerce the obedience of the individual Will, due to the fact that the individual Will “sins against its [i.e. the democratic Will’s] own being.”24 Summarising thus far, the Bogotán writes that “continued faith in the democratic ideal interferes with the immediate objectives of the authoritarian democrat, who enslaves in the name of freedom and awaits the coming of a god from without the depraved masses.”25 Thus in the context of Man’s supposed omnipotence, Gómez recalls democracy’s resulting abuse of technology and the “inexorable industrial exploitation of the planet.”26

According to Nicolás Gómez Dávila, the sovereign Will reigns in liberal and individualistic democracies, while the authentic Will reigns in collective and despotic democracies. In his characterisation of the democratic religion, the Author of the Scholia holds that “the transformation of a liberal and individualistic democracy, into a collective and despotic democracy, does not molest the democratic intention, nor does it depart from its promised objectives.”23 This is because the law of the democratic Will has the mandate to coerce the obedience of the individual Will, due to the fact that the individual Will “sins against its [i.e. the democratic Will’s] own being.”24 Summarising thus far, the Bogotán writes that “continued faith in the democratic ideal interferes with the immediate objectives of the authoritarian democrat, who enslaves in the name of freedom and awaits the coming of a god from without the depraved masses.”25 Thus in the context of Man’s supposed omnipotence, Gómez recalls democracy’s resulting abuse of technology and the “inexorable industrial exploitation of the planet.”26 The geneology of Gnosticism is not foreign to Gómez: “the birth of gnosis can evidently be traced to the pre-Christian era, yet its poison has evolved in the shadow of Christianity.”46 Thus the Bogotán ceases to associate Platonism – to which he is endeared – with Gnosticism and directs his suspicions towards Stoicism47 – which he despises: “The Greek roots of Gnosticism spätantike are not found in Platonic dualism but in Stoic monism.”48

The geneology of Gnosticism is not foreign to Gómez: “the birth of gnosis can evidently be traced to the pre-Christian era, yet its poison has evolved in the shadow of Christianity.”46 Thus the Bogotán ceases to associate Platonism – to which he is endeared – with Gnosticism and directs his suspicions towards Stoicism47 – which he despises: “The Greek roots of Gnosticism spätantike are not found in Platonic dualism but in Stoic monism.”48 In the second century A.D., Gnosticism was customarily concerned with the Fall of the divine entity; Manicheanism, associated with the gnostic dualist religious currents begotten by Mani in the third century A.D., concerned itself with the duality of and struggle between Good and Evil. After contact with Christianity, Gnosticism assumed the religious elements of Judaism and Christianity, e.g. revelation per se, and in particular the revelation of Christ and the revelation contained in the Scriptures. In the womb of Christianity, Gnosticism stimulates numerous heresies (e.g. Valentinius of Phrebonis and his disciples). Manichaeism is presented as a continuation of Gnosticism, and the inheritors of both currents are the Pualines, Bogomils and Cathars. Gómez does not fully agree with this classification and seems to contradict it, as he earlier writes in Textos I:

In the second century A.D., Gnosticism was customarily concerned with the Fall of the divine entity; Manicheanism, associated with the gnostic dualist religious currents begotten by Mani in the third century A.D., concerned itself with the duality of and struggle between Good and Evil. After contact with Christianity, Gnosticism assumed the religious elements of Judaism and Christianity, e.g. revelation per se, and in particular the revelation of Christ and the revelation contained in the Scriptures. In the womb of Christianity, Gnosticism stimulates numerous heresies (e.g. Valentinius of Phrebonis and his disciples). Manichaeism is presented as a continuation of Gnosticism, and the inheritors of both currents are the Pualines, Bogomils and Cathars. Gómez does not fully agree with this classification and seems to contradict it, as he earlier writes in Textos I: Another famous Gnostic is Valentine, who studied Platonism and the secret wisdom of Egypt in Alexandria, and who attended Isidore’s lectures. He established two schools: the Eastern (Alexandria) and the Italian (Rome). The Eastern School interprets the Book of Genesis and the Evangelia, and develops the theory of the Eons which emanate in primordial pairs (Jesus is here one of the greatest Eons). There is a fundamental difference between the ‘good god’ (the Most High primordial Absolute71) and the Demiurge of the world. Equally, Man is represented dualistically. Within him co-exist two elements: the first, originating from the Evil Demiurge and his Angels (impulses are the bad spirits); the second originate from the ‘good god’. Redemption is necessary. It is made possible through the revelation of Jesus Christ. The Eastern School speaks of three types of Man:

Another famous Gnostic is Valentine, who studied Platonism and the secret wisdom of Egypt in Alexandria, and who attended Isidore’s lectures. He established two schools: the Eastern (Alexandria) and the Italian (Rome). The Eastern School interprets the Book of Genesis and the Evangelia, and develops the theory of the Eons which emanate in primordial pairs (Jesus is here one of the greatest Eons). There is a fundamental difference between the ‘good god’ (the Most High primordial Absolute71) and the Demiurge of the world. Equally, Man is represented dualistically. Within him co-exist two elements: the first, originating from the Evil Demiurge and his Angels (impulses are the bad spirits); the second originate from the ‘good god’. Redemption is necessary. It is made possible through the revelation of Jesus Christ. The Eastern School speaks of three types of Man: