lundi, 25 mars 2013

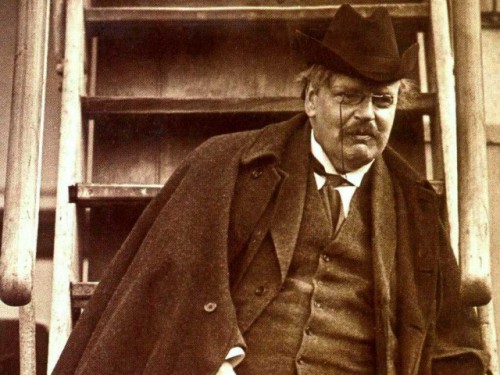

Chesterton the prophet of menacing Americanisation

1920: Chesterton the prophet of menacing Americanisation

Ex: http://english.pravda.ru/

But to-day personal liberties are the first liberties we lose.

In 1920 Chesterton visits America where he gives some lectures. The British (yet Catholic) genius is intimidated by this great country which horrifies and amazes then many European writers. Think of Kafka or Celine who describe a curious mega-machine.

Yet America happens -at least for Chesterton- to be a problem, because this is the country that will become the matrix of globalization (we all agree that being that matrix ruin the ancient Americans as a people). And when the author of father Brown gets to the control area, he is asked some very indiscreet questions such as: are you an anarchist? Then the questionnaire asks him naively if he is "ready to subvert by force the government of United States!" And what would answer our poet? ''I prefer to answer that question at the end of my tour and not the beginning'.

The questionnaire is not over. It asks then if the traveller is a polygamist! This time Chesterton is somewhat upset, like should have been the future travellers when asked if they are Nazis, anti-Semites or of course communists, Islamists or terrorists (what else, carnivores?). And he unleashes this terrible phrase:

Superficially this is rather a queer business. It would be easy enough to suggest that in this America has introduced a quite abnormal spirit of inquisition; an interference with liberty unknown among all the ancient despotisms and aristocracies.

So, let us think of inquisitive America as the land of the modern inquisitors (I think of course of Dostoyevsky). And, as if he had known we were doomed to an endless clash of civilizations between Muslims and Yankees, Chesterton evokes his visit to Jordan and compares with bonhomie Arab administration to the American one:

These ministers of ancient Moslem despotism did not care about whether I was an anarchist; and naturally would not have minded if I had been a polygamist. The Arab chief was probably a polygamist himself.

Of course Chesterton, having quoted the Muslim world, had to speak of prohibition. That American prohibition too is hard to swallow for our drinker of beer (he deals with the subject -and with Islamism too- in the scaring novel the flying inn). And beyond the classical denunciations of hypocrisy and Puritanism, prohibition inspires him the following witty lines:

But to-day personal liberties are the first liberties we lose. It is not a question of drawing the line in the right place, but of beginning at the wrong end. What are the rights of man, if they do not include the normal right to regulate his own health, in relation to the normal risks of diet and daily life?

Chesterton knew he was entering in a no smoking area. The Americanization of the world would mean an exigent agenda of rules and orders to comply in all fields. It is linked to the reign of the lawyers and congressmen, the cult of technique, a past but resilient Puritanism and of course the desire to homogenize all migrants. And he concludes on this matter with his sarcastic and efficient remark:

To say that a man has a right to a vote, but not a right to a voice about the choice of his dinner, is like saying that he has a right to his hat but not a right to his head.

Another subsequent menace is the Anglo-American friendship. Chesterton guesses that the anglo-American condominium means a general police of the planet and a future world order. The end of his strange and genial book is dedicated to the future new world order, whose prophet and agent is the famous sci-fi writer H.G. Welles. The motivation of this world state is mainly... fear, the artificial fear of the machines (think now of gun control).

He tells us that our national dignities and differences must be melted into the huge mould of a World State, or else (and I think these are almost his own words) we shall be destroyed by the instruments and machinery we have ourselves made.

But America has given to Chesterton enough reasons to fear its matrix, its efficiency and its blindness too. This is why America is too the magnet of heretic and modernist H.G. Wells. A country founded by Illuminati and masons has to become the mould and model of all.

Now it is not too much to say that Mr. Wells finds his model in America. The World State is to be the United States of the World... The pattern of the World State is to be found in the New World.

And although he speaks English and is an Anglo-Saxon, Chesterton, who is above all a Christian, a democrat and a humanist who mainly enjoys French and Russian peasants, then plundered by bolshevists, and he understands the American menace: the Americanisation of this planet, Americanisation that nothing will stop. The American menace consists in destroying any resisting nation in order to create the new united states of the world.

The idea of making a new nation literally out of any old nation that comes along. In a word, what is unique is not America but what is called Americanisation. We understand nothing till we understand the amazing ambition to americanise the Kamshatkan and the hairy Ainu.

Let us be more humoristic, but not optimistic. For the new American order will be established on the models of a nursery. This is where the blatant American feminism interferes:

And as there can be no laws or liberties in a nursery, the extension of feminism means that there shall be no more laws or liberties in a state than there are in a nursery. The woman does not really regard men as citizens but as children. She may, if she is a humanitarian, love all mankind; but she does not respect it. Still less does she respect its votes.

Our European commission works like this nursery. And of course our genius thus seizes American paranoia and the perils of modern pseudo-sciences, say for instance the theory of the gender. As if he was predicting infamous patriot act, Chesterton writes:

Now a man must be very blind nowadays not to see that there is a danger of a sort of amateur science or pseudo-science being made the excuse for every trick of tyranny and interference. Anybody who is not an anarchist agrees with having a policeman at the corner of the street; but the danger at present is that of finding the policeman half-way down the chimney or even under the bed.

That's not all. Why this American matrix imposes her strength so easily? Chesterton has already remarked that American political order incites citizens - or pawns- to be repetitive, trivial and equal: I think they too tend too much to this cult of impersonal personality. Thanks to fast-foods and commercial centres, business cult and universities, television and movies' omnipresence, this model has been applied in fifty years everywhere, event in the resilient Muslim countries, making the globalization more a mind-programmed attitude than a free will. But this is where we are.

But friendship, as between our heroes,

can't really be: for we've outgrown

old prejudice; all men are zeros,

the units are ourselves alone.

Eugene Onegin

Chesterton, what I saw in America, the project Gutenberg e-book.

Nicolas Bonnal

00:05 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : américanisation, états-unis, angleterre, g.k. chesterton, littérature, lettres, lettres anglaises, littérature anglaise |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Les commentaires sont fermés.