dimanche, 21 juillet 2013

Hommage à Jean Guenot

Hommage à Jean Guenot

Marc Laudelout

Il est notre vétéran du célinisme. Né en 1928 (quelques années avant Alméras, Gibault, Hanrez et Godard), Jean Guenot est l’un des derniers célinistes à avoir rencontré le grand fauve. Il n’avait alors qu’une trentaine d’années et, comme le releva Jean-Pierre Dauphin, il fut l’un de ceux qui, au cours de ces entretiens, renouvelèrent le ton de Céline. Lequel n’avait été approché jusqu’alors que par des journalistes aux questions convenues.

Une quinzaine d’années plus tard, il édita lui-même son Louis-Ferdinand Céline damné par l’écriture qui lui vaudra d’être invité par Chancel, Mourousi et Polac. L’année du centenaire de la naissance de l’écrivain, il récidiva avec Céline, écrivain arrivé, ouvrage allègre et iconoclaste. Professeur en Sorbonne, Jean Guenot a oublié d’être ennuyeux. Ses cours sur la création de textes en témoignent ¹.

Au cours de sa longue traversée, Guenot s’est révélé journaliste, essayiste, romancier, auteur de fictions radiophoniques, animateur et unique rédacteur d’une revue d’information technique pour écrivains pratiquants qui en est à sa 27ème année de parution. Infatigable promeneur dans les contre-allées de la littérature, tel que l’a récemment défini un hebdomadaire à fort tirage ².

Linguiste reconnu ³, c’est son attention au langage et à l’oralité qui fit de son premier livre sur Céline une approche originale à une époque où l’écrivain ne suscitait guère d’étude approfondie. Lorsqu’à l’aube des années soixante, Jean Guenot s’y intéresse, Céline est loin d’être considéré comme un classique. Trente ans plus tard, les choses ont bien changé. L’année du centenaire, Guenot établit ce constat : « Louis-Ferdinand Céline est un écrivain aussi incontesté parmi ceux qui ne lisent pas que parmi ceux qui lisent ; parmi les snobs que parmi les collectionneurs ; parmi les chercheurs de plus-values les plus ardents que parmi les demandeurs les plus aigus de leçons en écriture». Nul doute que lui, Guenot, se situe parmi ceux-ci. C’est qu’il est lui-même écrivain. Et c’est en écrivain qu’il campe cette figure révérée.

Un souvenir personnel. Si je ne l’ai rencontré qu’à deux ou trois reprises, comment ne pas évoquer cet après-midi du printemps 1999. Il était l’un des participants de la « Journée Céline » 4. Comme pour mes autres invités, je commençai par lui poser une question. Ce fut la seule car il se livra à une époustouflante improvisation pertinente et spirituelle à la fois. Des applaudissements nourris et prolongés saluèrent son intervention. C’est dire s’il compte parmi les bons souvenirs des réunions céliniennes que j’organisai alors à l’Institut de Gestion, quai de Grenelle.

On l’a longtemps confondu avec Jean Guéhenno. Sans doute la raison pour laquelle il abandonna l’accent aigu de son patronyme. Aujourd’hui l’académicien – qui d’ailleurs ne se prénommait pas Jean mais Marcel ! – n’est plus guère lu. Jean Guenot, lui, l’est toujours par les céliniens. Et s’ils sont amateurs d’écrits intimes, ils n’ignorent pas davantage l’écrivain de talent qu’il est 5.

Marc LAUDELOUT

1. Ce cours en vingt leçons, diffusé sur Radio Sorbonne, est disponible sous la forme de dix cassettes-audio diffusées par l’auteur. Prix : 80 €. Voir le site http://monsite.wanadoo.fr/editions.guenot.

2. Le Canard enchaîné, 5 juin 2013.

3. Clefs pour les langues vivantes, Éditions Seghers, coll. « Clefs », 1964.

4. Difficile de ne pas avoir la nostalgie de cette époque : outre Jean Guenot, mes invités étaient, ce 3 avril 1999, Éliane Bonabel, André Parinaud, Pierre Monnier, Paul Chambrillon, Anne Henry et Henri Thyssens, excusez du peu !

5. Le troisième tome de son autobiographie vient de paraître : Mornes saisons évoque ses souvenirs de l’occupation et fait suite à Sans intention et Ruine de Rome. Il y aura cinq tomes au total. Prix : 40 € chaque volume.

00:05 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : céline, jean guenot, france, littérature, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature française, marc laudelout |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 20 juillet 2013

L’Iran, de la “révolution blanche” à la révolution tout court

L’Iran, de la “révolution blanche” à la révolution tout court

Janvier 1978-janvier 1979. C’est au moment où elle se modernisait que la monarchie des Pahlavi s’est défaite dans la confusion. De là date l’essor de l’islamisme radical.

Janvier 1978-janvier 1979. C’est au moment où elle se modernisait que la monarchie des Pahlavi s’est défaite dans la confusion. De là date l’essor de l’islamisme radical.

Une tasse de thé, un dernier regard, Mohammad Réza Pahlavi quitte son palais presque vide, le 16 janvier 1979. Dans les jardins, il retrouve la chahbanou, puis gagne l’aéroport international de Téhéran. Un petit groupe les attend, mais ni ambassadeur étranger ni ministre. Des militaires supplient le chah de rester. Le général Badreï, chef de l’armée de terre, s’agenouille selon un vieil usage tribal et lui baise les genoux. Le chah enlève ses lunettes, le relève. Il pleure en public. À Chapour Bakhtiar, nommé à la tête du gouvernement deux semaines plus tôt, le 31 décembre 1978, il dit : « Je vous confie l’Iran et vous remets entre les mains de Dieu. »

Le chah pilote lui-même son Boeing 707 jusqu’à la sortie de l’espace aérien iranien. Il craint une attaque surprise. Commence pour le souverain une longue errance. Rongé par un lymphome, repoussé par tous, il trouve asile en Égypte où il mourra le 27 juillet 1980. Il régnait depuis le 16 septembre 1941 et allait avoir 61 ans.

Moins de dix ans plus tôt, il avait célébré à Persépolis les 2 500 ans de l’Empire perse dont il se voulait le continuateur. En même temps, son régime exaltait la modernisation de l’Iran et la “révolution blanche”, ce plan ambitieux de réformes lancé en 1963. La “grande civilisation” à laquelle le chah avait rendu hommage semblait de retour.

Mais à quel prix ! Omniprésence de la Savak (la police politique), pouvoir autocratique, cassure entre la capitale et la province, fracture entre une élite occidentalisée et le peuple, autisme du chah qui ignore l’aspiration de la société à intervenir dans la vie politique, corruption, vénalité, et hausse des prix. À ceux qui évoquent les ravages sociaux et politiques de l’inflation, le chah répond : « Mon gouvernement m’assure du contraire. Vous ne répercutez que des bavardages de salon ! »

La “révolution blanche” a heurté les plus traditionalistes de la société iranienne, les chefs de tribus et une partie du clergé conduite par un mollah nommé Ruhollah Khomeiny. Né en 1902, celui-ci nie toute valeur au référendum qui doit approuver la “révolution blanche”. C’est surtout la proclamation de l’égalité entre homme et femme et la modernisation du système judiciaire qui le font réagir car il estime que ce sont deux atteintes aux préceptes de l’Islam et du Coran. Sans oublier que la réforme agraire est, dit-il, préparée par Israël pour transformer l’Iran en protectorat…

De Qom, ville sainte du chiisme, Khomeiny provoque le chah le 3 mai 1963. Il est arrêté. Suivent trois jours d’émeutes, les 15, 16 et 17 juin, 75 victimes, 400 arrestations et un constat : l’alliance “du rouge et du noir”, une minorité religieuse active et fanatisée avec les réseaux clandestins du Toudeh, le parti communiste iranien. Pour éviter la peine de mort à Khomeiny, des ayatollahs lui accordent le titre de docteur de la loi faisant de lui un ayatollah. Libéré, il récidive en 1964 et s’installe en Irak.

Ces oppositions, le chah les connaît. Elles le préoccupent. Il lance un appel aux intellectuels pour qu’ils en discutent en toute liberté. En avril 1973 se réunit le “Groupe d’études sur les problèmes iraniens”, composé de personnalités indépendantes. En juillet 1974, un rapport est remis au chah qui l’annote, puis le transmet à Amir Abbas Hoveida, son premier ministre. « Sire, lui répond-il, ces intellectuels n’ont rien trouvé de mieux pour gâcher vos vacances. N’y faites pas attention, ce sont des bavardages. » En fait, il s’agit d’un inventaire sans complaisance de l’état du pays complété de mesures correctives avec cet avertissement : si elles ne sont pas prises au plus vite, une crise très grave pourrait éclater. Cinq mois plus tard, le chef de l’état-major général des forces armées remet à son tour un rapport confidentiel et aussi alarmant que celui des intellectuels : l’armée résistera à une agression extérieure mais un grave malaise interne peut mettre en danger la sécurité nationale.

Ces deux avertissements venus du coeur même du régime restent lettre morte. Un nouveau parti officiel créé en 1975, un nouveau premier ministre nommé en août 1977 ne changent rien : les ministres valsent, les fonctionnaires cherchent un second emploi, le bazar de Téhéran gronde. Or dès l’année 1976, le chah sent que la maladie ronge son avenir. « Six à huit ans », lui a dit le professeur français Jean Bernard. C’est un homme fatigué qui affronte la montée de la violence révolutionnaire dans son pays.

D’Irak, Khomeiny redouble ses attaques. Le chah, dit-il, n’est qu’« un agent juif, un serpent américain dont la tête doit être écrasée avec une pierre ». Le 8 janvier 1978, un article paru dans un quotidien du soir de Téhéran fait l’effet d’une bombe. Il s’agit d’une réponse virulente à Khomeiny, qui a été visée au préalable par le ministre de l’Information. Or la polémique mêle vérités et mensonges. Le lendemain, à Qom, des manifestants envahissent la ville sainte : un mort, le premier de la révolution. Le 19 février, quarante jours après ce décès, le grand ayatollah Shariatmadari organise à Tabriz une réunion commémorative. À nouveau, du vandalisme, des morts, des blessés. L’engrenage manifestation-répression est engagé. Et à chaque quarantième jour, à Téhéran, à Tabriz, à Qom, se déroule une manifestation qui tourne à l’émeute. La police appréhende des jeunes gens rentrés récemment des États-Unis et connus pour leur appartenance à des groupes d’extrême gauche, ou des activistes sortis des camps palestiniens, des individus ne parlant que l’arabe. Les forces de l’ordre ne tentent quasi rien contre eux.

Le pouvoir s’affaiblit et s’enlise. Le chah nie la réalité, ignore le raidissement du clergé, continue à raisonner en termes de croissance de PIB. Et puis les Britanniques et les Américains ont leur propre vision de la situation ; ils conseillent de pratiquer une ouverture politique et de libéraliser le régime : le général Nassiri, cible de la presse internationale et qui dirigeait la Savak depuis 1965, est écarté en juin 1978. Loin de soutenir le chah, comme le faisait Richard Nixon, le président Carter envisage son départ et son remplacement. Au nom des droits de l’homme, les diplomates américains poussent aux dissidences les plus radicales. Une ceinture verte islamiste, pensent-ils, est plus apte à arrêter l’expansion du communisme soviétique.

Le 5 août 1978, le chah annonce des élections “libres à 100 %” pour juin 1979, une déclaration considérée comme un signe de faiblesse. Le 11, débute le ramadan. Des manifestations violentes éclatent à Ispahan : pour la première fois, des slogans visent directement le chah. Le 19, se produit un fait divers dramatique : un cinéma brûle, 417 morts. Un incendie criminel. L’auteur ? Des religieux radicaux ? La Savak ? Le soir même, la reine mère donne un dîner de gala. L’effet sur l’opinion est désastreux, alors que les indices orientent l’enquête vers l’entourage de Khomeiny.

Le nouveau premier ministre, Jafar Sharif- Emami, surnommé “Monsieur 5 %” tant il prélève de commissions, déclare sous le coup de l’émotion “la patrie en danger”. Le 7 septembre, 100 000 personnes manifestent à Téhéran avec des ayatollahs : des portraits de Khomeiny apparaissent. La loi martiale est décrétée pour le lendemain 8. Les manifestants prennent de vitesse police et armée. Ils veulent occuper la “maison de la Nation” et y proclamer une “République islamique”. Le service d’ordre tire en l’air, des tireurs embusqués ouvrent le feu sur la foule. C’est le “vendredi noir”, soigneusement « préparé et financé par l’étranger » affirment les auteurs. Au total, 191 victimes. La rupture entre le régime et les partisans de Khomeiny est totale.

Le chah est anéanti. « Jamais, confie-t-il, je ne ferai tirer sur mon peuple ! » Lui qui croyait être tant aimé se sent trahi : « Mais que leur ai-je donc fait ? ». Un seul souci l’habite : éviter la guerre civile, sa hantise. Le “vendredi noir” marque le début de son inexorable chute.

Le désordre et l’anarchie s’installent ; Khomeiny gagne la France, reçoit intellectuels et journalistes (mais pas ceux de Valeurs actuelles à qui les auteurs de l’ouvrage que nous citons en référence rendent hommage) qui raffolent de l’ermite de Neauphle-le-Château ; en Iran, les marches en sa faveur se multiplient et façonnent l’image d’une révolution romantique et démocratique ; les Américains organisent en secret la phase finale de leur plan : neutraliser l’armée iranienne et le haut état-major fidèles au chah. Les jeux sont faits.

« L’Iran des Pahlavi n’était certes pas parfait, mais il était en pleine modernisation, écrira Maurice Druon dans le Figaro du 12 novembre 2004. Fallait-il pousser à le remplacer par un régime arriéré, animé par un fanatisme aveugle ? L’essor de l’islamisme radical date de là. »

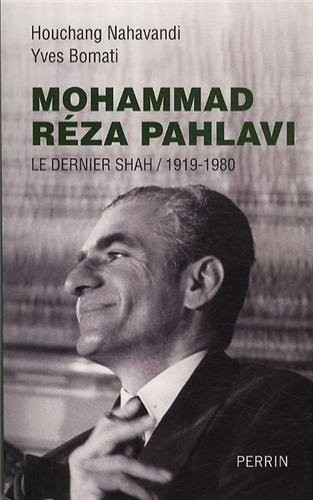

À lire Mohammad Réza Pahlavi. Le Dernier Shah/ 1919-1980, de Houchang Nahavandi et Yves Bomati, Perrin, 622 pages, 27 €.

00:05 Publié dans Histoire, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : histoire, politique internationale, iran, moyen orient, shah, shah d'iran, révolution islamiste, livre, houchang nahavandi |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 19 juillet 2013

Il ritratto di Ungern Khan

Foglie e pietre

Il ritratto di Ungern Khan

Sessantasei (adesso sarebbero novantadue ndr) anni fa, all’alba del 17 settembre 1921, cadeva fucilato a Novonikolajevsk, secondo altri a Verkhne-Udinsk, presso il confine mongolo, il comandante della divisione asiatica di cavalleria, barone Román Fiodórovic von Ungern-Sternberg, ultimo difensore della Mongolia “esterna” indipendente e della Siberia “bianca”. Con la morte del “Barone pazzo” nulla piú si opponeva al dilagare dell’esercito bolscevico di Blücher nell’Estremo Oriente siberiano e la fase guerreggiata della Rivoluzione si concludeva.

L’effimera meteora del Barone e le disperate imprese della sua divisione non ebbero, in fondo, un effetto determinante su quest’ultimo scorcio della Guerra Civile, specialmente dopo il crollo dell’esercito bianco di Kolcak che, battuto il 14 novembre 1919 ad Omsk, aveva praticamente cessato di esistere. Invece, l’importanza del barone Ungern e del suo variopinto esercito, formato da Cosacchi della Trans-baikalia, da Buriati, Mongoli, volontari Tibetani e Guardie Bianche di ogni provenienza, era soprattutto di natura spirituale. Il Barone, religiosamente affiliato ad una corrente tantrica facente capo allo Hutuktu di Ta-Kuré e suo braccio militare durante l’anno in cui fu padrone della Mongolia esterna, aveva sin dal principio, cioè sin dalla conferenza panmongola di Cita del 25 febbraio 1919, dichiarato la sua intenzione di ristabilire la teocrazia lamaista nel cuore dell’Asia, «affinché da lí partisse la vasta liberazione del mondo».

La controrivoluzione era per lui solo un pretesto per evocare sul piano terreno una gerarchia già attuata su quello invisibile. Questa gerarchia doveva proiettarsi su un mandala, un mesocosmo simbolico, il cui centro sarebbe stata la “Grande Mongolia”, comprendente, oltre alle sue due parti geografiche, l’immenso spazio che dal Baikal giunge allo Hsin-Kiang e al Tibet. Ivi, pensava, si sarebbe attuata la rigenerazione del mondo sotto il segno del Sovrano dell’agarttha (“inafferrabile”) Shambala, la “Terra degli Iniziati”, ove Zla-ba Bzan-po e i suoi 24 successivi eredi perpetuavano il segreto insegnamento del Kalacakra, la “Ruota del Tempo”, loro impartito dal Risvegliato 2500 anni fa.

2500 anni è esattamente la metà del ciclo di 5000 che, secondo la tradizione, separa l’apparizione dell’ultimo Buddha terrestre, Gautama Sakyamuni, dall’avvento del successivo Maitreya, figura probabilmente mutuata dallo zoroastriano Mithra Saosyant, “Mithra il Salvatore” (difatti l’iconografia buddhista lo rappresenta tradizionalmente come un principe “seduto al modo barbarico”, cioè assiso all’europea). Lo stesso Hutuktu di Urga, che Ungern, liberandolo dai Cinesi, aveva ristabilito sul trono, terza autorità nella gerarchia lamaista dopo il Dalai Lama di Lhasa e il Panc’en Lama di Tashi-lhumpo, era teologicamente considerato quale proiezione fisica (sprul-sku) di Maitreya, prefigurazione, quindi, del Buddha venturo. Ungern, consapevole nonostante questa vittoria della sua fine imminente, si rendeva conto di trovarsi in un istante “apicale” del divenire della storia, come se fosse nel cavo fra due onde, un attimo prima che rovinino in basso. Pertanto, nel suo breve periodo di governo ad Urga (dal 2 febbraio all’11 luglio 1921) cercò di tramutare questo istante in un “periodo senza tempo” che permettesse allo Hutuktu di compiere la sua opera spirituale, liberandolo dalla pressione esterna dei due poteri che incombevano: la Cina dei “Signori della Guerra” dal Sud, e la valanga bolscevica che muoveva inarrestabile dal Nord, dalla Siberia.

Erano tempi terribili in cui, piú che dal potere delle armi, gli eventi sembravano determinati da forze promananti da una sorta di magia infera. Coloro che furono testimoni degli sconvolgimenti determinati dalla Rivoluzione di Ottobre ricordano la spaventevole automaticità medianica con cui le “forze rivoluzionarie” demolivano le strutture della vita civile cosiddetta “borghese” e le vestigia dell’ordine antico. Le masse si coagulavano in quegli strati della società in cui maggiormente era assente il principio dell’“Io” autocosciente, fra i miseri, i vagabondi, gli allucinati sopravvissuti dai Laghi Masuri e dalle battaglie della Galizia, i fanatici, i tarati e tutti coloro per i quali la ferocia belluina era alimento quotidiano dell’anima. Ai rivoluzionari non si scampava: mossa come da un’ispirazione demoniaca, la “giustizia del popolo” colpiva infallantemente i nemici della Rivoluzione un momento prima che si muovessero. Il Terrore era guidato da una occulta saggezza che nulla aveva a che fare con la brillante intelligenza di coloro (Trockij, Kamenev, Zinoviev ecc.) che lo avevano scatenato e pensavano di dirigerlo: una saggezza che realmente promanava dall’elemento preindividuale della “massa”, come le forze fisico-chimiche che provocano un terremoto o la fuoriuscita della lava da un vulcano.

Ungern chiaramente si rendeva conto di tutto ciò e, dalle sue conversazioni con l’ingegnere Ossendowski, già ministro delle Finanze nel governo di Kolcak, risulta evidente come egli cercasse di evocare misticamente il principio opposto, quello solare, che segnava il suo stendardo, riferendosi ad una cultura, quella tantrico-buddhista, che da due millenni lo coltivava. Soltanto che la sua ascesi personale non poteva diventare il mezzo strategico di vittoria per i suoi cinquemila cosacchi, russi sí, mistici forse, ma fatalmente appartenenti ad un mondo orientato verso un’esperienza dello Spirito volta al mondo sensibile esteriore. Nel suo Uomini, Bestie e Dèi, che è la narrazione della sua fuga dalla Siberia alla Mongolia, Ossendowski ci ha lasciato un’impressionante descrizione degli eventi, ma, molto di piú, dell’allucinata atmosfera che regnava sulla ufficialità che attorniava il Barone e fra le sue truppe, sottomesse da anni a spaventose fatiche e ad una disciplina rigidissima e, per giunta, consapevoli del disastro imminente. La narrazione dell’Ossendowski verrà in seguito aspramente criticata (fra gli altri dallo stesso Sven Hedin) per la parte riguardante i suoi viaggi fra gli Altai e la Zungaria. Resta, però, intatta la sua testimonianza sulla figura e sulle avventure del Barone e, soprattutto, sul senso “magico” del destino che ivi si compiva.

Ungern chiaramente si rendeva conto di tutto ciò e, dalle sue conversazioni con l’ingegnere Ossendowski, già ministro delle Finanze nel governo di Kolcak, risulta evidente come egli cercasse di evocare misticamente il principio opposto, quello solare, che segnava il suo stendardo, riferendosi ad una cultura, quella tantrico-buddhista, che da due millenni lo coltivava. Soltanto che la sua ascesi personale non poteva diventare il mezzo strategico di vittoria per i suoi cinquemila cosacchi, russi sí, mistici forse, ma fatalmente appartenenti ad un mondo orientato verso un’esperienza dello Spirito volta al mondo sensibile esteriore. Nel suo Uomini, Bestie e Dèi, che è la narrazione della sua fuga dalla Siberia alla Mongolia, Ossendowski ci ha lasciato un’impressionante descrizione degli eventi, ma, molto di piú, dell’allucinata atmosfera che regnava sulla ufficialità che attorniava il Barone e fra le sue truppe, sottomesse da anni a spaventose fatiche e ad una disciplina rigidissima e, per giunta, consapevoli del disastro imminente. La narrazione dell’Ossendowski verrà in seguito aspramente criticata (fra gli altri dallo stesso Sven Hedin) per la parte riguardante i suoi viaggi fra gli Altai e la Zungaria. Resta, però, intatta la sua testimonianza sulla figura e sulle avventure del Barone e, soprattutto, sul senso “magico” del destino che ivi si compiva.

Ricordo perfettamente la straordinaria impressione che suscitò nell’Europa distratta e frenetica degli anni Venti, anche fra i lettori piú materialisti e intenti negli affari contingenti, la relazione sul collegamento mistico fra lo Hutuktu, il Bodhisattva incarnato, il Barone Ungern e il Re del Mondo, presenza invisibile ma concretamente percepibile che conferiva un significato trascendente al sacrificio a cui i Cosacchi, il fiore dei popoli russi, andavano incontro. Questo motivo del “Re del Mondo” dette fuoco alle polveri di innumerevoli discussioni, specialmente fra coloro che si accorgevano che non si trattava di una invenzione letteraria. Fra gli altri, lo stesso René Guénon lo sottopose ad una critica serrata nel suo Le Roi du Monde, dimostrandone la fondatezza, in un’epoca in cui la Scienza orientalistica praticamente nulla sapeva del mito di re Chandra-bhadra (tib. Zlâ-ba Bzan-po) depositario di una sentenza segreta comunicatagli dal Buddha, e soprattutto ignorava la saga del suo Regnum spirituale, una specie del Castello del Graal, che storici e geografi si sono in seguito affannati a ricercare in vari luoghi del Tibet e della valle del Tarim in Asia Centrale: regno visibile solo agli Eletti, che però si renderà manifesto a tutti sotto il ventiquattresimo erede di Chandra-bhadra, quando la sapienza del Kalacakra emergerà per illuminare gli uomini circa la coincidenza della loro interiorità purificata e l’Universo degli archetipi.

La leggenda di questo Barone baltico, di stirpe germanico-magiara che, rivestito della tunica gialla del lama sotto il mantello di ufficiale imperiale, e spiegando davanti agli squadroni lo stendardo mongolo, procede “nella direzione sbagliata”, verso Ovest anziché verso Est, ove chiaramente si sarebbe salvato, è tipicamente russa, ricollegandosi al motivo sacrificale della zértvjennost’ (“l’offrirsi come vittima”) per l’istaurazione del Figlio della Benedizione sulla Terra Madre, che in veste poetica era stata enunciata dallo stesso Solovjèv.

Nell’ultimo rapporto ufficiale, tenuto ai princípi di agosto 1921, quando la divisione asiatica di cavalleria si trovava sul fiume Selenga intenta ad interrompere la Transiberiana fra Cita e Kiakhta, egli impartí l’ordine apparentemente assurdo di compiere la conversione verso Ovest, indi verso Sud, avendo come meta gli Altai e la Zungaria. In quella occasione disse esplicitamente al generale Rjesusín che si proponeva di raggiungere, attraverso lo Hsin Kiang cinese, niente di meno che la “fortezza spirituale tibetana”, ove rigenerare se stesso e i laceri resti della sua divisione. Assassinato il suo amico Borís la sera stessa dagli ufficiali in rivolta e morti gli ultimi fedeli, egli mosse solitario verso una direzione che non aveva piú rapporto con la realtà geografica del luogo e militare della situazione, nel postremo tentativo, non di salvare la vita, bensí di ricollegarsi prima di morire con il proprio principio metafisico: il Re del Mondo.

La sua disperata migrazione verso il Sole che tramonta era in realtà un ultimo atto di culto verso la Luce che aveva sorretto le sue imprese. Trascorse la sua ultima notte di libertà nella yurta del calmucco Ja lama. Il Barone si avvide, forse, del significato del nome del suo ospite: Ja, abbreviazione in dialetto khalka del mongolo Jayagha, “fato”, “esistenza”, “destino”, karma. E il “fato” lo consegnerà la mattina seguente alle Guardie Rosse di Shentikín, il fiduciario di Blücher. Era il 21 agosto. Regolarmente processato nel sovjet di Novonikolayevsk, senza che gli venissero toccate le spalline e la croce di San Giorgio, viene accusato di “complotto anti-sovietico per portare al trono Mikhail Romanov, efferatezze ed assassinio di masse di lavoratori russi e cinesi”. Condannato, viene fucilato due giorni piú tardi.

Nello stesso tempo, in un angolo della lontanissima Europa, nella Germania sconquassata del primo dopoguerra, il mito del Re del Mondo giungeva per vie misteriose a gruppi di giovani intellettuali, corroborando con il suo simbolo solare i nuovi meditatori del “Vril” e le assisi della Thule-Gesellschaft.

*da “Un tempo, un destino”, in «Letteratura – Tradizione», II, 9

00:05 Publié dans Eurasisme, Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : ungern von sternberg, ungern-sternberg, eurasie, eurasisme, histoire, révolution russe, russie, russie blanche |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 18 juillet 2013

La CIA et l’empire de la drogue

La CIA et l’empire de la drogue

par Laurent Glauzy

Ex: Ex: http://actionsocialeetpopulaire.hautetfort.com

Si les acteurs du trafic de l’opium semblent avoir changé, la CIA n’en a pas moins accru son emprise… et, depuis la fin de la guerre froide, sa connivence avec l’intégrisme musulman pour lequel le contrôle de l’opium est vital. Le territoire afghan a vu depuis sa libération une augmentation de 59 % de sa production d’opium sur une superficie de 165 000 hectares. En termes de production annuelle, cela représente 6 100 tonnes, soit 92 % de la production mondiale. L’ONU rapporte que dans la province de Helmand, la culture de l’opium a augmenté de 162 % sur une superficie de 70 000 hectares. Ces statistiques sont d’autant plus alarmantes que ce sont seulement 6 des 34 provinces afghanes qui en sont productrices. Les Nations-Unies ont bien entendu proposé une aide au développement économique pour les régions non encore touchées par cette culture. Ce à quoi le président afghan Hamid Karsai a répondu de manière très explicite et franche que l’on devait d’abord réviser les succès du « camp anti-drogue »…

Les Skulls and Bones et les services secrets

L’implication des Etats-Unis dans la production et la consommation de la drogue n’est pas récente. Pour en comprendre les raisons, il faut remonter plus de 150 ans en arrière, car elle fait partie intégrante de l’histoire des Etats-Unis et de celle des sectes supra-maçonniques. Des noms très célèbres apparaissent sur le devant de cette scène très macabre. Ce sont pour la plupart des membres de la société initiatique des Skull and Bones (Les Crânes et les Os) de l’Université de Yale qui se partagent le monopole de la commercialisation de l’opium. L’instigatrice de cet ordre est la famille Russell, érigée en trust. Les Russell en constituent encore l’identité légale.

De quoi s’agit-il ?

En 1823, Samuel Russel fonde la compagnie de navigation Russell & Company qui lui permet de se ravitailler en Turquie en opium et d’en faire la contrebande avec la Chine. En 1830, avec la famille Perkins, il crée un cartel de l’opium à Boston pour sa distribution avec l’Etat voisin du Connecticut. A Canton, leur associé s’appelle Warren Delano jr, le grand-père de Franklin Delano Roosevelt. En 1832, le cousin de Samuel Russell, William Hintington, fonde le premier cercle américain des Skull and Bones qui rassemble des financiers et des politiques du plus haut rang comme Mord Whitney, Taft, Jay, Bundy, Harriman, Bush, Weherhauser, Pinchot, Rockefeller, Goodyear, Sloane, Simpson, Phelps, Pillsbury, Perkins, Kellogg, Vanderbilt, Bush, Lovett. D’autres familles influentes comme les Coolidge, Sturgi, Forbes, Tibie rejoindront cette nébuleuse fermée. Ces noms démontrent qu’au fil des générations la démocratie reste l’affaire de cercles pseudo-élitistes. Le pouvoir ne se partage pas ! A noter aussi que tous ces membres du Skull and Bones ont toujours entretenu des liens très étroits avec les services secrets américains… L’ancien président des Etats-Unis George Bush sr., ancien étudiant à Yale, a par exemple été directeur de la Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) en 1975-76. Ajoutons que pour cet établissement, tout a commencé quand quatre diplomates y ont formé le Culper Ring, qui est le nom d’une des premières missions des services secrets américains montée par George Washington dans le but de recueillir des informations sur les Britanniques pendant la Guerre d’Indépendance.

En 1903, la Divinity School de Yale monte plusieurs écoles et hôpitaux sur tout le territoire chinois. Le très jeune Mao Tse Toung collaborera plus tard à ce projet. La diplomatie actuelle de ces deux pays en est-elle une des conséquences ? Quoi qu’il en soit, le commerce de l’opium se développe. Son sous-produit, l’héroïne, est un nom commercial de l’entreprise pharmaceutique Bayer qu’elle lance en 1898. L’héroïne reste légalement disponible jusqu’à ce que la Société des Nations l’interdise. Paradoxalement, après sa prohibition, sa consommation augmente de manière exponentielle : on crée un besoin et une population dépendante ; des textes définissent ensuite les contours d’une nouvelle législation, fixent de nouvelles interdictions, afin d’accroître la rentabilité d’un produit ou le cas échéant d’une drogue.

L’implication des hauts commandements militaires

Imitant leurs homologues américains, les services secrets français développent en Indochine la culture de l’opium. Maurice Belleux, l’ancien chef du Service de documentation extérieure et de contre-espionnage (SDECE), confirme le fait lors d’un entretien avec le Pr Alfred Mc Coy : « Les renseignements militaires français ont financé toutes les opérations clandestines grâce au contrôle du commerce de la drogue en Indochine. » Ce commerce sert à soutenir la guerre coloniale française de 1946 à 1954. Belleux en révèle le fonctionnement. Nos paras sont contraints de prendre l’opium brut et de le transporter à Saïgon à bord d’avions militaires, où la mafia sino-vietnamienne le réceptionne pour sa distribution. Nous constatons une fois encore que la République n’a aucune honte à souiller la nation. De leur côté, les organisations criminelles corses, sous couvert du gouvernement français, réceptionnent la drogue à Marseille pour la transformer en héroïne avant sa distribution aux Etats-Unis. C’est la French Connection. Les profits sont placés sur des comptes de la Banque centrale. M. Belleux explique que la CIA a récupéré ce marché pour en continuer l’exploitation en s’appuyant au Vietnam sur l’aide des tribus montagnardes.

Cet élément doit être conjugué à l’évidente supériorité de l’armée américaine pendant la guerre du Vietnam. Une seule année aurait suffi pour que les Etats-Unis remportassent ce conflit. Mais cette logique n’est pas celle des Affaires étrangères et des cercles d’influence mondialistes.

En 1996, le colonel Philip Corso, ancien chef de l’Intelligence Service ayant servi dans les troupes commandos d’Extrême-Orient et en Corée, déclare devant le National Security Council que cette « politique de la défaite » entrait dans les plans de la guerre froide. C’est après 1956 que le colonel Corso, assigné au Comité de coordination des opérations du conseil de sécurité nationale de la Maison Blanche, découvre cette politique de la « non-victoire » opérée au profit de la guerre froide et de l’expansion du communisme.

En revanche, la lutte pour le monopole de l’opium s’intensifie. Dans ce trafic, nous trouvons des militaires appartenant au haut commandement de l’armée vietnamienne, comme le général Dang Van Quang, conseiller militaire du président Nguyen Van Thieu pour la sécurité… Quang organise un réseau de stupéfiants par l’intermédiaire des Forces spéciales vietnamiennes opérant au Laos, un autre fief de la CIA.

Le général Vang Pao, chef de tribu des Meo, reçoit l’opium à l’état brut cultivé dans toute la partie nord du Laos et le fait acheminer à Thien Tung à bord d’hélicoptères appartenant à une compagnie de la CIA, Air America. Thien Tung est un énorme complexe construit par les Etats-Unis. Il est appelé le « Paradis des espions ». C’est ici que l’opium du général Pao est raffiné pour devenir de l’héroïne blanche.

La CIA intervient à ce stade de la fabrication pour sa distribution. Et Vang Pao dispose à cet effet d’une ligne aérienne personnelle. Dans le milieu, elle est nommée « Air Opium ».

De l’héroïne dans le cercueil des GI’s !

Les points essentiels du trafic sont établis à proximité des bases aériennes américaines comme celle de Tan Son Nhut. Une partie de la drogue est d’ailleurs destinée à la consommation des militaires américains. Chapeauté par les réseaux de Quang, la plus grande part de la production est expédiée à Marseille d’où elle part à Cuba, via la Floride. Là-bas, le gang des Santos Trafficante contrôle le marché. Ce détour est essentiel ; il faut récupérer les paquets d’héroïne dissimulés à l’intérieur des corps des soldats américains morts que l’on rapatrie. De plus, leur sort indiffère les représentants politiques. Le secrétaire d’Etat Henri Kissinger déclarera aux journalistes Woodward et Berristein du Washington Post que « les militaires sont stupides, ils sont des animaux bornés dont on se sert comme des pions pour les intérêts de la politique extérieure ». Les bénéfices seront investis en Australie, à la Nugan Hand Bank.

Le cas du Cambodge est semblable à celui de ses voisins. Après son invasion par les Etats-Unis en mai 1970, un autre réseau voit le jour. Des régions entières sont destinées à la culture de l’opium. La contrebande est contrôlée par la marine vietnamienne. Elle dispose de bases à Phnom Penh et le long du Mékong. Une semaine avant le début des hostilités, une flotte de cent quarante navires de guerre de la Marine vietnamienne et américaine commandée par le capitaine Nyugen Thaanh Chau pénètre au Cambodge. Après le retrait des troupes américaines, le général Quang, considéré dans son pays comme un grand trafiquant d’opium, séjourne quelque temps sur la base militaire de Fort Chaffee dans l’Arkansas, et s’installe à Montréal. Concernant la Birmanie, elle produit en 1961 quelques mille tonnes d’opium, que contrôle Khun Sa, un autre valet de la CIA. Le gouvernement américain est son unique acquéreur.

L’éradication de la concurrence

Devons-nous croire aux principes d’une politique anti-drogue? En 1991, le Pr Alfred Mc Coy dénonce à la radio un rapport institutionnel volontairement trop proche entre le Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) et la CIA. Avant la création de ce premier organisme, dans les années 1930, est fondé le Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) qui a pour fonction gouvernementale et secrète la vente des narcotiques. Le FBN emploie des agents dans le cadre d’opérations clandestines. Ils seront transférés après 1945 dans le nouvel Office of Strategic Services (OSS), précurseur de la CIA. Ces imbrications rendent impuissant le DEA contre les magouilles de la CIA. Car la drogue qui entre aux Etats-Unis est sous le monopole de la CIA qui en détient tous les circuits de distribution depuis le sud-est asiatique et la Turquie. Quand, en 1973, le président Richard Nixon lance « la guerre à la drogue », il provoque la fermeture du réseau de la contrebande turque qui passait par Marseille. Le résultat en est une augmentation directe de la demande d’héroïne provenant du Triangle d’Or et particulièrement de Birmanie.

Aujourd’hui, nous avons suffisamment de recul pour nous interroger lucidement et remettre en doute le rôle officiel de la CIA et la politique des Etats-Unis dans le monde. Nous observons que le commerce de l’opium et des autres drogues, par des cartels dont les populations blanches et européennes sont la cible, s’opère depuis toujours entre la CIA et des partenaires présentés au grand public comme des « ennemis à abattre » : le communisme et l’islam.

Cet état de fait est d’autant plus grave qu’il intervient après les événements du 11 septembre 2001, le conflit du Kossovo dont l’emblème national sous Tito était un pavot, et l’invasion de l’Irak par l’armée américaine. La CIA et la drogue apparaîtraient donc comme les piliers cachés mais bien réels d’une stratégie mondialiste ayant pour but l’asservissement des peuples.

Enfin, les arguments étudiés prouvent d’une part que le pouvoir n’est pas l’affaire du peuple et d’autre part, que notre actualité et notre avenir ne sont pas le fruit du hasard, mais le résultat de plans mis en œuvre secrètement par des groupes d’influence extrêmement dangereux.

Laurent Glauzy

Extrait de l’Atlas de Géopolitique révisée (Tome I)

Laurent Glauzy est aussi l’auteur de :

Illuminati. « De l’industrie du Rock à Walt Disney : les arcanes du satanisme ».

Karl Lueger, le maire rebelle de la Vienne impériale

Atlas de géopolitique révisée, tome II

Chine, l’empire de la barbarie

Extra-terrestres, les messagers du New-Age

Le mystère de la race des géants

00:05 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : cia, services secrets, services secrets américains, drogues, narco-trafics, politique internationale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 17 juillet 2013

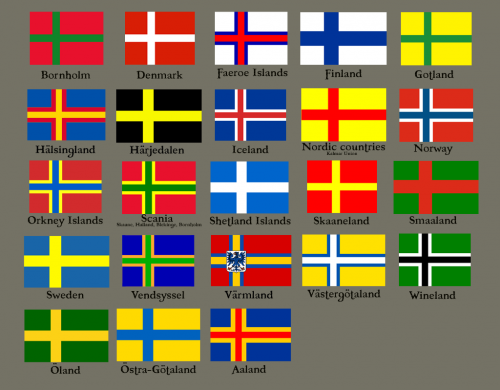

A Brief Introduction to the Nordic Imperium School

A Brief Introduction to the Nordic Imperium School

Vibeke Østergaard

I hesitated writing this principally as a result of time constrains but to a lesser extent because only two other lansmen seem to be on this list and the material will likely seem remote to the Americans and Englishmen on the list. I have received a great number requests to compose such an introduction from members and others that follow this list and I do feel that the school deserves some attention from Eurocentric advocates in general which in the end caused me give the matter cursory attention. I have purposely avoided raising the matter of the esoteric/mystic writings many of the authors because I do not wish to offend the non Heathen majority on this list and I feel that ideological issues can be dealt with adequately without raising the matter. I also chose not to deal with the matter of proponents of the school being active in the Legionary Movement as others have covered the matter far better then I can.

This very brief introduction to the Nordic Imperium School of thought prior to ‘45 is meant to simply provide a bit of background on some of the key figures and concepts. I should state that due to my background I'm biased towards Føroyskt, Danish and Icelandic figures rather then Swedish and Norwegian ones. This is not say they are any less important to the school but that I am more familiar with the former and they do resonate a bit closer to my views which is why I emphasize them. Also, note that because I am covering a great deal of material spanning several nations and decades my treatment will have to be superficial do to both the format of this forum and time pressures which prevent the application of sufficient criticism, care to style and detail beyond a course degree. If anyone wishes clarification on any of the points I touched on just let me know.

I think that the best place to start is with the political writings of Venzel Hammershaimb who is best known as the father of modern Faroese. What became the basis of V.U. Hammershaimb's contribution to what latter became known as the Nordic Imperium stemmed from his Føroyskt Antologi which recounts various local mythology, folklore and songs but is best known as serving as the basis for our current grammar and spelling which was standardized here during the 1890's.

In substantive terms, the proposition advanced by Hammershaimb was that the spiritual essence of a people are best expressed by song and lore which in turn express itself in the folkways of a people. That which makes a people unique are commonalities in ascetics which reflect the environment in which they live and the self perceptions that results from belonging to a common stock lending continuity and hence, shared identity and purpose . This view holds that dilution and alienation in terms both folkish and individual come from two sources: external domination and co-mingling with other kindreds which are seen as detrimental because they end aesthetic commonality and inherited perceptions of folklore upon which domestic concord depends leading to what he called an "anti culture" which is similar to what is now in vogue in the states and the West as a whole.

This basic notion of ethno-cultural compatibility and continuance was presented as an argument against imperialism and the preservation of all of the unique expressions of Scandinavian folkishness entailed some form of transnational cooperation. Unfortunately, the consequences of this notion were never articulated by Hammershaimb. Instead, a more traditional form of nationalism was taken from his writing and speeches were adopted by the patriotic and Romantic poet Nólsoyar-Poul Poulson whose sense of organic folkishness was infused with resentments of colonial injustice. This oppressive history began with the clerical dictatorship of Bishop Erlendur during the early 1100s and grew worse the dispossession of the Alping ( People's Assembly) in 1380. This unfortunate pattern culminated with the savagely cruel reign of the Von Gabel dynasty which lasted from the mid 1600s till the early 1700s and finally the famines of the early 1800's which when combined with massive taxes to support the Danish crown nearly lead to our literal extinction.

In Iceland the politicized lyricism of the Fjölnismenn served to provide a similar substance to a traditional yet vibrant form of nationalism just as our most beloved poet and nationalist Heðin Brú (alias Hans Jacob Jacobsen) expounded an organic and romantic view of blood, soil and folkways defining both Faroese culture and the Nordic essence from which it springs. These expressions of poetic nationalism and Nordic essence were not important so much for their substance as they were for their literary style and the passions they evoked among lansmen. Other equally important sources for nationalist inspiration came from the very well known author . Mikkjal a Ryggi's ( 1901-1987) who authored the 1940 classic of local history "Midhvingas" and William Heinesen (1900-1991) whose most famous work is the folkish collection Soga Friðrik which is of as a great an importance as the Poetic Eddas.

During the 1920s and a 30s a great deal of progress happened in ideological terms thanks to the writing of Jón Ögmundarson who coined the term "Nordic Imperium" writing a book by the same name in 1925. Basically, the substance of his thought revolved around a critique of French and Italian Fascism and Corporatism of the era which was later supplemented with an expansive treatment of earlier themes and a critique of contemporary German National Socialism in his 1932 work arguably mistitled "Aphorisms".

Ögmundarson accepted the well established notion that both capitalism and traditionally conceived versions of socialism and syndicalism were two sides of the same coin so to speak because they both represented materialistic perspectives divorced from the what he called the "Nation Organic" or the traditional folkways and mores which reflected the temperament of a people free from foreign domination and materialistic influence. The concept of the Nation Organic simply means a continuum of values and perceptions derived from a society based upon shared ancestry providing a common sense of identity and purpose. The rationale for preserving such a society is that the sense of individual purpose and security it provides was viewed as best for preserving societal cohesion across generations in a world seen as largely hostile, unstable, despotic and prone to decadence and ultimately savagery.

Both capitalism and traditionally conceived versions of socialism and syndicalism resulted in the imposition of a particular class upon society causing personal and class based alienation resulting in materialist based interest groups becoming estranged from the state and the state from society. The end result of the dominance of materialism over spiritualism was seen in this view as leading to the death of civilization with nations becoming nothing more then sales/production districts in which the basest elements of a devolved society outbreed the vanguard leaving nothing but decadence combined with civil insecurity. Such a debased entity was seen as simply collapsing under internal strain or being over run by a more vigorous and sound alien stock.

As such, Ögmundarson found sympathy with the notion that socialism should be seen not in terms of class war but in terms of the ascension of the Nation Organic over the state. In doing so he shared he sentiments of National-Socialists like Valois, Berres and Sorrel whose expressions of National Revolutionary thought sought to transcend both democracy and the materialism which were viewed as being at the heart the heart of syndicalism, socialism, capitalism and the societal

decay they engender.

His dispute with such theorists stemmed from a rejection of corporatism/national syndicalism conceived in terms of vertical integration which he saw as an illusion to total statism. He considered the former preferable to Bolshevism in that it avoided class domination but undesirable because it did not resign the state to a position of serving what he considered the ultimate purpose of the state's existence: the progression of the Nation Organic. Instead, he saw the value of Sorel's take on socialism in that its intention was the moral regeneration of society as a whole rather then class based advocacy which he combined with his view that folkways represent a common spirit that is a manifest expression of the biologic. As such, this view holds that the degradation of one leads to a decline of the other and a corresponding rise in materialism which by nature is universalistic, destructive in societal terms and dysgenic to the point of eventual liquidation of the folk.

Like all proponents of the school, Ögmundarson was violently opposed to the welfare state which he saw as nothing more then statism used to encourage sloth and dependancy upon a materialistic state that destroys traditional institutions and communal relations. This view holds social democracy as simply an incremental form of Bolshevism resulting in spiritual and ultimately biologic decay.

On an institutional basis, the assertion of society over materialism resulted in a rejection of corporatist arrangements in favour of employee ownership as means for the distribution of productive economic assets. This conception has individual firms being organized on the basis of voluntary guilds like federations for the purpose of securing finance for capitol goods, capacity expansion and basic materials from usury free banks funded by withholdings taken from company sales receipts or publicly funded block grants, in the modern American style of term, in the case of capital intensive industries. Another aspect of these guild like organization were that they were envisioned as being responsible for providing primary and trade based education.

Do to the long history of onerous taxes to support a distant potentate came the notion that taxes were to be set by a "Chamber of Producers" comprised of delegates selected by popular vote within their respective guilds every three years. Also according to this scheme, the electorate was tasked with determining the tax rates and basic budget for the public sector via periodic plebiscites. The actual composition of proposed budgets being open to anyone that could obtain support of 5% of the electorate for their scheme. Rival budgets meeting this criteria are submitted to the plebiscite with three rounds of voting reducing the options to the two most popular options in a manner similar to current French presidential elections. The electorate was viewed as consisting of the head of each tax paying house hold and all unmarried tax payers with gross recipients of welfare, felons, drunks and mentally incompetent/disturbed members of society

expressly forbidden from voting.

Less well defined was the nature of the autocrat, entitled the "Amtmaður", who was entrusted with what is commonly referred to as executive power. The principle political tasks of the Amtmaður is: appointing judges and ministers, enacting the public sector budget, providing for defense and representing the folk state abroad. The legitimacy of the Amtmaður is viewed as being derived solely from his ability to promote and maintain folkish renewal. As such he is tasked with enacting eugenic policies similar to those found else where in Scandinavia at the time, promoting both traditional and high arts as well preventing the influx of non Nordic influence in cultural, economic and political terms.

The selection of the Amtmaður is not covered in adequate detail. Instead, Ögmundarson simply states him to be a populist leader that heads a folkish uprising during a period of immense societal turmoil. The school terms such a struggle for folkish resurgence as "Insurgent Traditionalism" which basically expresses tradition as being under a constant state of siege from the forces of materialism/universalism which ultimately manifest themselves in terms of biologic decay which, if sufficiently advanced, destroys the possibility of folkish renewal and therefor is viewed as being ultimately destructive . The only method for the removal of the Amtmaður was briefly touched upon as the responsibility of an armed citizenry which seems to have been taken from the traditional American notion of a militia.

As to the matter of the Nordic Imperium, such is viewed principally in terms of racial Nordics expressing themselves in terms of the advancement of the Nation Organic throughout Scandinavia via the expression of traditional folkways and mores. Such an expression of Nordic traditionalism is portrayed as an anti-Imperialistic doctrine which calls for the Amtmaður of various nations to form a Nordic League for handling common issues of concern such as trade, ecological matters, responses to cultural threats posed by non Nordic media and such. The league was also to be tasked with the matter of raising an volunteer expeditionary legion along the lines of the war time Legionary Movement to help repulse any efforts by the Bolsheviks to expand in the West as well as supporting the development of indigenous, non imperialistic forms of folkish resurgence throughout Europa via propaganda.

In "Aphorisms" Ögmundarson condemned Mussolini as "promoting primitive state worship over organicism and the needs of the Italian people." He condemned the Faisceau of Valois as "Abandoning the transcendence of democracy, capitalism and Bolshevism in favour of a class free despotism opposed to materialism but offering nothing in it's place." contemporary Futurism was like wise portrayed as "Nothing more then an adolescent rejection of what one is by birth and the obligations entailed as a result in favour of a directionless and violent vitality imbued stylish inconsequentials"

As to Hitler the same text said: ‘ The heart of the current revolution is best expressed by Mr. Hitler's comment that ‘The [Nation-] State in itself, has nothing whatsoever to do with any definite economic concept or a definite economic development. It does not arise from a compact made between contracting parties, within a certain delimited territory, for the purpose of serving economic ends. The State is a community of living beings who have kindred physical and spiritual natures, organized for the purpose of assuring the conservation of their own kind and to help towards fulfilling those ends which Providence has assigned to that particular race or racial branch.' This notion despite having great merit, is unfortunately called into doubt by efforts to deny folkish restoration by creating a state that risks reflecting statist rather then the organic principles of Insurgent Traditionalism as a result of the centrality of the Leadership Principle to his doctrine."

Anders Rüsen was a Danish devotee of Ögmundarson who founded the so called "primal wing" of the school which placed a heavier emphasis upon the rhetorical style of the poets mentioned earlier infused with the mysticism of Von List and a historic view of folkish resurgence and decline was prominent detailed in a two volume 1929 monograph entitled "Permanent Tradition, Permanent Modernism". The former differed from most of his work which was not expressly political and instead focused upon antiquarian research and Heathen mysticism. A theme found in this and other works by Rüsen and his compatriots is that tradition and modernity should not be seen as contending elements in Nordic history but rather that Nordic folkways are always facing extinction do to the harshness of local environments, the vastly superior resource and demographic strength of other European nations and the dysgenic impact upon Nordicdom that resulted from migration and conquest during the Viking era.

The natural weaknesses mentioned above were overcome with native ingenuity of both technological and societal variants which in turn provided a stable, comfortable existence begetting high material expectations and a weakening of traditional social arrangements. These in turn beget materialism and relations based upon one's association with the means of production that ultimately lead to individual and class based alienation and finally societal breakdown.

As societal decay advances traditionalism responds based upon reaction (which is conceived in the classical French sense of the term) or what Rüsen referred to as a theoretically simple construct although complex in terms of application known as "a synthesis of reversal" which is nothing more then the adoption of thematic themes, policies or institutional theory that is a product of some form of universalism used as a means of lending the image of modernity to a traditional ideology as a tactical ploy. If such a ploy is successful and staves off societal collapse the inovation often becomes integrated into, and as result modifies, the broader national tradition.

The modification is seen as a "natural progression" if the if the append theory/ theme/institution is tempered with a Burke like notion of prudence preserving the broader integrity of tradition. Conversely, such appendages can also have long term consciences that fundamentally undermine tradition in ways that are not predictable and as a result, such progressions are fraught with danger. A large portion of the first volume and all of the second installment of "Permanent Tradition, Permanent Modernism" was dedicated to considering Christianity, in a relatively benign light, and parliamentarianism, in a highly negative fashion, from this perspective.

This view holds that imperialism and migration during the Viking era was a terrible mistake because it siphoned off the most vigorous stock of Nordic society to establish kingdoms in alien lands that could not possibly dominate the local populations and were instead biologically absorbed by the native populations. This dysgenic effect left the other great nations of Europa better able to threaten Nordic countries in addition to their shear size, imperial holdings and natural resources leaving Nordic nations continually under threat. As an aside, the primal wing held that imperial adventures undertaken by the great powers of Europa would destroy their economies and encourage the destruction of traditional societal relations leading first to social democracy then Bolshevism and the finally the end of what he termed "Europa Organic". His formative work on this mater was printed in late 1944 by Rüsen and entitled "Nationalism or Imperialism." Which was unfortunately, his last published work. The remainder of his life was spent fighting with a NS resistance group against allied occupation until his death in June of 1945.

It should be noted that despite his military efforts, Rüsen he was not an uncritical supporter of the NSDAP variant of National Socialism. Instead, he held sympathy for the notion of "Permanent National Socialism" which was advanced by fellow mystic Jan Rystrup in his major political text entitled "The Evolution of Folk Essence" published in 1938. When grossly over simplified, this perspective held that any form of National Socialism based upon the "leadership principle" was doomed to be despotic by reflecting the societal interests of the selectorate that brought the leader to power rather then society as a whole. Rystrup maintained that the NSDAP state was not an ideal expression of National Socialism because it's centralized character and militarism necessitated it becoming an expression of the materialistic interests of factions within the state rather then the Nation Organic.

A further weakness of the NSDAP state according to this view was that it's desire for imperialistic conquest outside of ethnic German regions to the East compromised the organic foundations of National Socialism by draining the vitality and natural resources of Germany in endless wars of colonial subjugation which concentrates state power while diminishing the forces of tradition via interaction with foreigner land and mores.

By contrast, Permanent National Socialism provides interest articulation for all elements of traditional society while the state serves primarily as a force of cultural conservatism interfering in societal matters only to prevent the imposition of class based interests and degenerative trends from interfering with domestic harmony. Such a system is ultimately defined in terms of guildism, decentralization, folkish traditionalism and a limited state.

Despite the substantive objections to Hitler's regime both were active in the legionary movement and armed resistance to allied occupation. Both saw the allies as actively promoting miscegenation, materialism, cultural nillism and the destruction of Europa. That they ultimately served the Axis reflected not so much an indorsement but rather faint praise of an alternative which they felt would wither more quickly in the event of victory then would the allied forces of Bolshevism and capital.

Eyðun við Dennstad took a somewhat different approach by emphasizing the notion that common folk cultures should serve as the basis for regional cooperation throughout Europa by encouraging the creation of a pan European alliance against both the materialism of bourgeois parliamentarianism which he saw as doomed to fall to Bolshevism and the technocratic/ statist tendencies characteristic of French and Iberian corporatism and fascism of the pre war period. As such, he promoted the notion of national boarders based upon folkish commonality and supported the unification of German speaking peoples, the unification of Flanders with Holland (ie. Dietsland) and the creation of Baltic and Slavic Imperiums with alliances based upon the Nordic model to serve as bulwark against bolshevism. These notions were advanced in a series of essays collected into two volumes entitled: "The Folk Nations and Spirituality of Insurgent Traditionalism I & II".

He also rejected the anti Christian rhetoric common to some of his compatriots within the school by saying that Christianity had become part of the Nordic tradition and character regardless of it's alien origin and should be accepted as a unifying element within society rather then encouraging a return to the religious wars of the past. His pragmatic view of Christianity was, to my mind, unsuccessfully grafted onto the folkish perspectives of Manfred Wittich, Franz Diederich and Kurt Heilbutz.

In terms of contributions to policy and institutional thought he advocated the notion that adherence to a single state or economic structure was incorrect and that a centralized, corporative structure was best suited for the promotion of heavy industry along the lines promoted by Valois and Charles Spinasse while maintaining the basic institutional structure of Ögmundarson in other areas. He also was passionate in defense of agrarian policy heavily tilted towards small farmers as stated by the likes of Gilbert and the American Distributists of the 1920s .

He supported agrarian policies principally because he viewed it as a way of preventing the concentration of wealth which he believed encouraged social unrest while promoting economic self sufficiency and folkish culture. He also was a strong proponent of Listian trade policies and the formation of a Nordic Customs Union base upon the old German model.

00:05 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : histoire, scandinavie, pays scandinaves, europe, affaires européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 16 juillet 2013

Stotternder Magus

Vor 225 Jahren gestorben: Königsberger Philosoph J. G. Hamann

Königsberg war im 18. Jahrhundert deutsche Hauptstadt der Philosophie. Nicht nur Kant lebte und wirkte hier, sondern auch sein Antipode Johann Georg Hamann. Während der Aufklärer Kant die reine Vernunft lehrte, verurteilte Hamann diese Lehre als gewalttätig und despotisch und predigte stattdessen die Reinheit des Herzens.

Königsberg war im 18. Jahrhundert deutsche Hauptstadt der Philosophie. Nicht nur Kant lebte und wirkte hier, sondern auch sein Antipode Johann Georg Hamann. Während der Aufklärer Kant die reine Vernunft lehrte, verurteilte Hamann diese Lehre als gewalttätig und despotisch und predigte stattdessen die Reinheit des Herzens.

Gab es da etwa Anzeichen von Revierkämpfen? Wohl kaum. Königsberg war groß genug, um beide Denker zu verkraften, und Hamann ein zu kleines Licht, um Kant Konkurrenz zu bieten. Im Gegenteil, Kant verhalf dem mittelosen Kollegen 1767 zu einer Stelle im preußischen Staatsdienst bei der Königsberger Provinzal-Akzise und Zolldirektion. Was wie eine Strafversetzung erscheint, war für Hamann ein Glück, denn weil der am 27. August 1730 als Sohn eines Königsberger Baders und Wundarztes Geborene die Universität ohne jeden Abschluss verließ, hatte er nie – wie Kant – einen Anspruch auf einen Lehrstuhl. Im Gegensatz zu Kant war er Hobbyphilosoph, der aber dennoch von seinen Zeitgenossen wahrgenommen wurde. Goethe, der während seiner Studienzeit in Straßburg von Herder auf Hamann aufmerksam gemacht wurde, bekannte, dass ihm dessen geistige Gegenwart „immer nahe gewesen“ sei.

Für diese Anerkennung musste Hamann hart kämpfen. Nach seinem – vergeblichen – Studium der Theologie und Jurisprudenz schlug er sich als Hauslehrer im baltischen Raum durch, machte danach einige journalistische Versuche, ehe er auf Geheiß einer befreundeten Kaufmannsfamilie mit einem handelspolitischen Auftrag nach London reiste. Hier hatte der Lutheraner sein religiöses Erweckungserlebnis, indem er intensiv die Bibel studierte. Es war ein „Schlüssel zu meinem Herzen“, schrieb er.

Zurück in Königsberg blieb Hamann ein „Liebhaber der langen Weile“, von der er im Zollamt offenbar ausgiebig Gebrauch machte. Während der Dienststunden bewältigte er ein Lektürepensum, das ihn zu einem der letzten universal belesenen Polyhistoren reifen ließ. Seine Reflexionen über das Gelesene legte er in Gelegenheitsschriften und Briefen nieder, deren dunkler Redesinn oft schwer nachvollziehbar ist. Im Zentrum seines Denkens steht dabei das Verhältnis von Vernunft und Sprache. Da die menschliche Sprache mit Makeln behaftet sei, könne man mit ihrer Hilfe niemals zur höchsten Vernunft kommen. Das sokratische Nichtwissen blieb Hamanns letztes Wort.

Wer sich hier als Sprachphilosoph betätigte, hatte selbst einen Sprechfehler: Hamann stotterte sein Leben lang. So glaubte er einzig an das göttliche Wort, den Logos der Natur, in dem sich Gott offenbare. Den Stürmern und Drängern um Goethe kamen solche Gedanken gerade recht, wollten sie doch den Genie-Begriff der Aufklärer vom Sockel stoßen. Da sich Hamann bei seiner bibelfesten Argumentation wie die drei Magi aus dem Morgenland auf der Suche nach Christus begab, verlieh ihm der Darmstädter Geheimrat von Moser den ironischen Titel „Magus im Norden“.

Tatsächlich war Hamann nicht nur Wegweiser für den Sturm und Drang, sondern später auch für Philosophen wie Schelling und Kierkegaard oder Autoren wie Ernst Jünger. Einer seiner Bewunderer war auch der westfälische Landedelmann Franz Kaspar von Buchholtz, der Hamann, seine uneheliche Frau – eine Magd – und seine vier Kindern mit 4000 Reichstalern aus dem Fron beim Zollamt erlöste und ihn 1787 ins katholische Münster lotste. Nur ein Jahr später starb Hamann dort am 21. Juni 1788 – nur kurz vor einer geplanten Rückreise nach Königsberg.

Harald Tews

00:05 Publié dans Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : j. g. hamann, histoire, philosophie, 18ème siècle, allemagne |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 15 juillet 2013

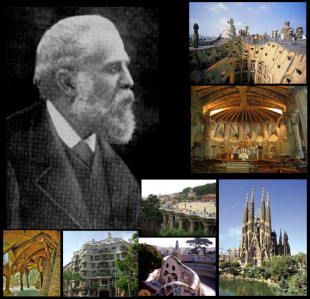

Antoni Gaudì, l’architetto di Dio

L’anniversario. Antoni Gaudì, l’architetto di Dio: un genio mistico, colto e rivoluzionario

Quando lo tirarono fuori da sotto il tram numero 30, i soccorritori pensarono fosse un barbone, magari in preda ai fumi dell’alcol. Malandato, con la giacca troppo larga, le tasche sfondate con dentro qualche noce e un po’ d’uva passa, i pantaloni lisi, le gambe fasciate per proteggerle dal freddo, magro, quasi diafano. Venne ricoverato in un ospedale per indigenti e solo il giorno successivo fu riconosciuto dal cappellano della Sagrada Familia. Ma era ormai troppo tardi. Era il 10 giugno del 1926 e Antoni Gaudì, l’architetto di Dio, morì senza riprendere conoscenza. Aveva 74 anni ed era nato a Reus, sulla costa a sud di Barcellona, il 25 giugno del 1852.

La strana morte del genio catalano, profeta del “modernismo” europeo, non fu altro che l’emblematica parabola di un personaggio straordinario, che malgrado ricchezza e celebrità visse una vita irregolare, fuori dal coro, interamente dedicata alla sua professione. Una professione che Gaudì interpretò sempre come strumento per creare una connessione fra uomo e Dio: «Chi cerca le leggi della natura per conformare ad esse opere nuove, collabora con il Creatore», era solito affermare.

In effetti ogni opera di Gaudì – dal Parc Güell alle famose case (Botines, Batllò, Milà), fino all’opera più celebre, ambiziosa e monumentale, la cattedrale neo-gotica della Sagrada Familia – è pregna di simboli e riferimenti culturali di carattere mistico. Un misticismo cristiano e cattolico, come ha sempre assicurato lo stesso architetto catalano e come conferma il processo di beatificazione di Gaudì avviato dal Vaticano nel 2000. Ma al tempo stesso frutto di secoli di tradizioni alchemiche ed esoteriche tramandate da società segrete e logge massoniche. Lo scrittore Josep Maria Carandell analizza nel suo libro El parque Güell, utopía de Gaudí, una grande quantità di dettagli di chiara radice massonica; mentre un altro suo biografo, Eduardo Cruz, assicura che fu rosacrociano e altri insinuano persino che ebbe tendenze panteiste ed atee.

Letture, voci, interpretazioni. Suffragate dall’indubbio simbolismo ermetico e alchemico presente in molte opere dell’architetto catalano: dalla X al fornello dell’alchimista, dall’albero della vita al labirinto, fino a svariati animali che assumono da secoli una simbologia iniziatica, come il pellicano, il serpente, il drago. Quel che è certo, però, è che il prossimo alcuni anni fa la Sagrada Familia – ormai costruita la 60 per cento – è stata consacrata niente meno che da Benedetto XVI, un Papa molto attento agli aspetti teologici del suo pontificato.

Del resto l’opera di Gaudì è per sua stessa ammissione ispirata alla natura: «Ciò che è in natura è funzionale, e ciò che è funzionale è bello. Vedete quell’albero? Lui è il mio maestro», diceva Gaudi a chi gli domandava da dove traeva le sue forme. Parole poco adatte a un architetto cripto-massone… «La Sagrada Familia o la Cripta della Colonia Güell, dove ogni elemento decorativo ha un profondo simbolismo religioso – ha scritto Michele Palamara – sono esempi di una fede fortissima radicata nel centro rurale dove Gaudì ha vissuto da bambino, e dove la professione del cristianesimo era l’anello di congiunzione fra l’individuo e la collettività».

Non bisogna dimenticare, inoltre, che molti dei presunti simboli alchemici e massonici fanno più riferimento alla tradizione classica che non a probabili messaggi per “iniziati”. Come nota Angela Patrono, se all’ingresso del Parc Güell troviamo un dragone a sorvegliare l’entrata dei padiglioni, si tratta di una citazione del mito del giardino delle Esperidi, dove Ercole – sconfitto il drago alato – può accedere per cogliere le mele d’oro. Eusebi Güell, committente dell’opera e principale mecenate di Gaudí, era infatti un appassionato di mitologia greca e intendeva fare del parco una nuova Delfi: un luogo incontaminato, ispirato alla città greca sede del tempio di Apollo, dio della poesia. E a chi sottolinea la presenza di arcani simbolismi persino nel progetto della Sagrada Familia, risponde lo stesso Antoni Gaudì, che ha sempre spiegato la presenza delle 18 torri come una rappresentazione dei 12 apostoli, dei 4 evangelisti, della Madonna e, la più alta di tutte, di Gesù. Le torri degli evangelisti sono sormontate da simboli della tradizione: un uomo, un toro, un aquila e un leone.

Che Gaudì, anche dopo la morte, venisse percepito come un importante esponente della cultura cattolica lo conferma pure un episodio avvenuto nel ’36, durante la guerra civile spagnola, quando un gruppo di militanti anarchici incendiò il suo studio, bruciando i preziosi progetti originali della cattedrale, e tentò persino di appiccare il fuoco al cantiere della Sagrada Familia. E questo benché l’architetto non fosse un simbolo dell’odiato potere centralista di Madrid, bensì un noto – anche se tiepido – simpatizzante della causa catalanista: nel ’24 venne persino fermato dalla polizia mentre si recava ad una messa celebrata in memoria degli eroi catalani morti nel 1714 in difesa della città.

Antoni Gaudì era figlio di calderai e proprio alle sue origini artigiane tributò sempre la sua capacità di dare forma ai progetti teorici. Si diplomò nel 1878 alla Scuola Superiore di Architettura di Barcellona, ma già prima riuscì a lavorare con i migliori architetti del tempo, anche per potersi pagare gli studi. La sua grande fortuna fu di incontrare un ricco industriale, rimasto estasiato da una vetrina per un negozio di guanti disegnata dal maestro in gioventù. Si trattava di Eusebi Güell, il quale, diventando il suo mecenate, gli diede massima fiducia e massima disponibilità economica. Tra la fine dell’Ottocento e i primi anni del Novecento, Gaudì realizza le sue opere più celebri, destinate a passare alla storia, riprendendo le linee dell’architettura araba, gotica e barocca e mischiandole con tratti innovativi e fantasiosi, elementi curvi, mosaici e ciminiere. La famosa Casa Milà, conosciuta come “la Pedrera”, sembra ricavata dalla roccia; in realtà la struttura è in acciaio ed è ricoperta da grandi blocchi di pietra lavorati. A partire dal 1910, però, rinunciò ad ogni altro incarico per dedicarsi esclusivamente all’edificazione della Sagrada Familia. Una chiesa che sapeva benissimo di non poter finire, data l’imponenza dell’opera e la scarsità di risorse economiche a sua disposizione. «Il mio cliente non ha fretta», ironizzava alludendo a Dio.

Nel 1915 Gaudí arrivò a chiedere l’elemosina tra i ricchi borghesi di Barcellona per continuare l’opera: stendendo la mano tra le strade e le case della città che lui stesso aveva contribuito ad abbellire, chiedeva “un centesimo per amor di Dio”. Fiorirono gli aneddoti e le leggende su un uomo che aveva rinunciato al denaro e alla fama per un’impresa che molti giudicavano improba. Ma per lui non era così: «Nella Sagrada Familia tutto è frutto della provvidenza, inclusa la mia partecipazione come architetto». Al suo funerale parteciparono migliaia di barcellonesi, dall’aristocrazia al popolino: gli studenti di Architettura portarono il feretro di Antoni Gaudì a spalle fino al cantiere della Sagrada Familia, dove venne interrato nella cripta che lui stesso aveva progettato e costruito.

00:05 Publié dans Architecture/Urbanisme | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook