Kerry Bolton

Kerry Bolton

The Banking Swindle: Money Creation and the State [2]

Black House Publishing, 2013

Kerry Bolton’s The Banking Swindle is a great introduction to the economics of the true Right, which aligns itself against the forces of usury. The topic of economics is quite neglected in the discourse of the modern Right, especially in the Anglosphere. Concerns about race, immigration, multiculturalism, or historical revisionism consume far more ink than the question of money, however behind all of these issues lies money power. Indeed Bolton refers to its paramount importance:

No other policy of the Right, in whatever part of the world, is possible without the need to first secure the economic and financial sovereignty of the state, and this can only be achieved when the State or Crown assumes the prerogative over banking and credit creation. The bottom line is that no State- and hence people- are truly free while any decisions that are made can be undermined and wrecked by decisions made in the boardrooms of global corporations, by the fluctuations of the world stock market, and by the power of bankers to turn off the credit supply if a state pursues policies not in the interest of the plutocracy… All other issues, including the Right’s now usually be-all issue of race and immigration, are secondary, and no Rightist government could implement Rightist policies until the sovereignty of credit creation is achieved.

The system of interest finance allows bankers to create money out of nothing and loan it at interest, which must be repaid with real production. As Gottfried Feder and Dietrich Eckart stated in their pamphlet, To All Working People, “Interest has to come from somewhere after all, somewhere these billions and more billions have to be produced by hard labour! Who does this? You do it, nobody but you! That’s right, it is your money, hard earned through care and sorrow, which is as if magnetically drawn into the coffers of these insatiable people . . .” Thus entire nations can be bound by debt and their physical assets seized to pay off the creditors who created their debt. Hence we see nations like Greece enduring austerity regimes, where the services are cut and the nation’s assets sold, to ensure that the bondholders do not lose their money. Over and over again people are told to tighten their belts, cut spending, and do without, in order to keep the financial system afloat. Yet during the Great Depression, alternatives to this system were popular and were advocated by nationalist and anti-liberal movements. Bolton illuminates this forgotten chapter in economic history.

Before addressing the various alternatives to the debt finance system, Bolton briefly discusses its history. He notes that while usury dates back to Mesopotamian times, with Babylon’s loans of seed-corn, the modern system of international finance, based out of the city of London, yet loyal only to profit, emerged with the expansion of commerce Age of Exploration and the weakened position of the anti-usury Catholic Church following the Reformation. The victory of the mercantile forces of Oliver Cromwell over the agricultural, feudal interests of Charles I in the English Civil War paved the way for financial domination. Cromwell maintained good relations with Dutch, Sephardic Jewish, and Huguenot merchants, paving the way for London to become the major financial centre in Europe.

The so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688 sealed this result, with the Catholic King James II deposed and replaced with the Dutch Protestant William III, who had borrowed heavily from Amsterdam’s banks to fight his wars. Under William II the Bank of England was chartered, establishing a private bank with the purpose of lending the throne money at interest. From 1700 to 1815, the national debt of Britain grew from 12 million pounds to 850 million, funded by this bank.

The Rothschild family, originally from Frankfort and branching out to Paris, Naples, Vienna, and London, became involved in the English struggle against Napoleon under Nathan Rothschild, utilizing their international network to gather information. It is necessary to note that Napoleon’s economic system sought to achieve autarky and the Bank of France limited dividends and extended credit at low interest rates to aid manufacturers rather than leave them indebted. A victory for Napoleon would have meant a tremendous loss for the forces of finance. The victory of the British Empire and its global expansion allowed the Rothschild family to extend their influence.

Nathan’s grandson “Natty” Rothschild cultivated links with imperialist Cecil Rhodes. But Rothschild was not a British imperialist for the sake of Britain, indeed he extended loans to the anti-British Boer government in 1892, much to displeasure of Rhodes. Rothschild simply saw the British Empire as the safest means of supporting commerce. As colonial expansion slowed, they adopted an internationalist line, abandoning the antiquated Empire that now served as a barrier to free trade, forging links with New York and Tokyo following the Second World War.

In recent history, it was the events of the Great Depression awakened many to the flaws of the interest finance system. The Federal Reserve, the private bank that controls the United States’ money supply, called in the loans from its 12 regional branches, who in turn financed the various local banks of the country, at the end of this transaction the ordinary debtor was forced to pay or face foreclosure. In the midst of this crisis, farmers were ordered to destroy stockpiles of food that couldn’t be purchased for lack of funds, while people went hungry. Unlike today, the people and their political leaders did not blindly follow the solutions offered by the same people who caused the problem, rather they sought out alternatives to usury. The interrelated concepts of state credit and social credit found widespread popular support.

The idea of state credit pre-dates the concept of social credit, which was codified by Major C. H. Douglas in the 1920s and 1930s. In a state credit system, the state prints its own money and uses it to purchase goods and services or loans it to producers at zero or minimal interest, rather than borrowing money from creditors at interest and having the people of the state work to pay the interest on these outside loans.

One early example of state credit was seen in Quebec in 1685, when the colony failed to receive funding from the crown. The Intendant of the Province, Monsieur de Meulle, faced with the inability to pay his troops, and having no ability to borrow money nor a press to print it, simply collected playing cards, cut them up, and used them as currency in the place of outside funds. This action saved the French crown 13,000 livres. The cards acted as scrip: arbitrary objects such as paper or tokens that serve as legal tender.

Scrip was used on the British Isle of Guernsey in 1820, when the state could neither secure outside loans nor increase taxes to raise the funds need to maintain and improve the local infrastructure. To deal with the situation the state issued 6,000 pounds worth of State Notes, which were used to pay for needed improvements on the island. While the idea of a state printing its own money and using it to pay for goods and services directly is dismissed as “funny money,” the Isle of Guernsey subsequently prospered from the creation of debt free currency. The only difference between this alleged “funny money” and regular money was that it was not created at a usurious interest by a private bank.

In the turbulent years of the Weimar Republic, when hyperinflation effected the value of the Mark, the Wära, issued by the Wära Barter Company, was notable example of economically successful scrip. Following the Great Depression in 1929, the employees of Hebecker in the village of Schwanenkirchen were paid in Wära, which the villagers accepted as valid currency. The resulting success in Schwanenkirchen was described as miraculous in the press and eventually 2000 corporations accepted it until it was banned in 1931. In the Austrian town of Woergl a similar to the Wära was implemented, where the mayor’s Local Relief Commission issued stamps to serve as scrip, which paid for new public works programs, which dropped unemployment. The Woergl stamp scrip was outlawed in 1933.

In the English-speaking countries, the events of the Great Depression fuelled interest in alternatives to the debt finance system, particularly the Social Credit system of Canada’s Major C. H. Douglas. The basic premise of the system is that the amount of money in circulation is never equal to the amount needed to consume the whole of what is produced. This is demonstrated by the “A+B Theorem.” Let A be the amount a producer pays his employees, and let B be the amount a producer spends on outside payments. The minimum amount needed to sustain the producer is the sum, A+B, however only A has purchasing power. Thus B is really a shortfall of purchasing power. To address the shortfall in purchasing power, Douglas proposed a “National Dividend,” paid by the state to the people, issued not as debt to be repaid, but as the birthright of the citizen.

A prominent exponent of this idea was the American poet Ezra Pound, who saw Italian Fascism as a vehicle for Social Credit. In New Zealand the poet Rex Fairburn adopted the ideas of Social Credit as well. Douglas’ tour of New Zealand also inspired Campbell Begg’s New Zealand Legion, which at one timed amassed 20,000 members. In Great Britain, the Green Shirts, an organization descended from the Anglo-Saxon and Medieval inspired Kibbo Kift scouting movement, rallied the unemployed and hungry to the idea of Social Credit. In 1936, Green Shirts founder John Hargrave was appointed an advisor to a Social Credit government in Alberta, Canada. However, the central government foiled attempts at properly implementing the system. W. K. A. J. Chambers-Hunter supported Social Credit ideas in Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists, under the premise that “British credit shall be used for British purposes.” In Canada, a Catholic organization called the Pilgrims of St. Michael, founded in 1935 by Louis Even and still extant, emphasized Social Credit as an alternative to the sinful usury based finance system.

Yet there was another Catholic crusader against usury that influenced the Pilgrims of St. Michael. In America, Canadian-born Father Charles Coughlin, the host of a popular Roman Catholic radio show for children, addressed their parents on broadcast on the issue of money, his well-received attack on usury lead to the creation of the Radio League of the Little Flower. By 1932 he had an audience of up to 45 million listeners. Originally a proponent of the New Deal, Coughlin broke with Roosevelt and created the National Union for Social Justice, which distributed his paper Social Justice. He demanded the abolition of private banking and returning the ability to print and regulate the money supply to Congress, in place of the Federal Reserve. However increasing opposition in the hierarchy of the Catholic Church and changes in radio regulations caused by the outbreak of World War II forced Coughlin to cease broadcasting in 1940 and in 1942 Social Justice was banned from the US mail.

While much of the popular outrage over the injustices of the debt-finance system died with World War II, it resulted in concrete political changes in several countries. Long before the Great Depression, the Australian Labour politician King O’Malley identified the banking system as the root of the common man’s misery stating, “The present banking system was founded on the idea that the many were created for the few to prey on. Debts are contracted for land, labour, products, and other commodities. When interest rises government bonds depreciate, holders sell to secure ready money to benefit by rise in interest. High rates of interest rapidly increase the indebtedness of the people.”

His proposed solution was the creation of a Commonwealth Bank that would serve as a national bank of the issue of currency without resorting to usury. Eventually, after much struggle, the Commonwealth Bank was instituted as a state-owned, but commercial bank, and it failed to issue state credit, however it’s first governor didn’t use private capital to fund the bank and was able to fund Australia’s government without imposing usurious interest upon the nation.

In the First World War, while other nations were paying 6% on their debt, the Commonwealth Bank only charged 1%, sparing Australia the ensuing economic turmoil. Until 1924, the Commonwealth Bank financed the construction of homes, roads, railways, and other forms of infrastructure at minimum charge, resulting in great prosperity. Yet in 1924, private interests took control of the governing directorate, and this came to an end.

Another political success in the Oceania was the New Zealand’s state housing program funded by the state credit from the Reserve Bank. This project reduced unemployment in the depths of the Great Depression. An initial 5 million pounds of state credit were issued, at minimal interest, without the backing of any other private financial institution. While the state housing project is widely lauded, the unorthodox method of its financing is barely commented upon in history books. The Banking Swindle does tremendous service to financial history by recounting the success of what is far too often dismissed as “funny money.”

The pivotal figure in the struggle for state credit in New Zealand was John A. Lee, a socialist influenced by the ideas of Social Credit, who outlined his vision in Money Power for the People. He stated, “that winning complete financial power as the first move toward a new social order,” realizing that state owned interests would be powerless if they depended upon private or foreign financing, which could be manipulated to produce detrimental effects on New Zealand’s people. This lesson has been lost upon many of the self-proclaimed socialist governments of the world, like Greece, whose socialist government borrowed millions from foreign investors only have austerity forced upon it by these usurers.

The principle of freedom from the chains of international finance appealed to the nationalists of the era as well, as noted by the BUF’s endorsement of “British Credit for British purposes.” One of the founding principles of the German Worker’s Party, which later become the National Socialist German Worker’s Party, was to break the bondage of interest. The primary economic mind behind them was Gottfried Feder, a founding member of the German Worker’s Party. Recognizing that interest gave money a power to reproduce itself at a cost to productive labour, Feder advocated the abolishment of income earned without physical or intellectual labour, a concept enshrined as the 11th point of the NSDAP. While the Marxists focused their ire on private property, Feder stated that “you never hear a word about, never a syllable, and there is nothing in the world which is such a curse on humanity! I mean loan capital!” Following the National Socialist assumption of power state credit was used to fund public works projects and the interest rates were limited by law. Hitler himself remarked:

All thoughts of gold reserves and foreign exchange fade before the industry and efficiency of well-planned national productive resources. We can smile today at an age when economists were seriously of the opinion that the value of currency was determined by the reserves of gold and foreign exchange lying in the vaults of the national banks and, above all, was guaranteed by them. Instead of that we have learned to realize that the value of a currency lies in a nation’s power of production, that an increasing volume of production sustains a currency, and could possibly raise its value, whereas a decreasing production must, sooner or later, lead to a compulsory devaluation.

In the realm of international trade, Germany directly bartered their surplus commodities for the commodities of other nations, avoiding the financial system’s commodity exchanges. Through a policy of economic self-sufficiency, above all avoiding the credit market’s snares, German was able to create full employment for its people. Henry C. K. Liu, a modern economist stated, “through an independent monetary policy of sovereign credit and a full-employment public works program, the Third Reich was able to turn a bankrupt Germany, stripped of overseas colonies it could exploit, into the strongest economy in Europe within four years, even before armament spending began . . . While this observation is not an endorsement for Nazi philosophy, the effectiveness of German economic policy in this period, some of which had been started during the last phase of the Weimar Republic, is undeniable.”

Furthermore, Germany’s Axis partners also pursued nationalist alternatives to the global financial system. In 1932 the Bank of Japan was reorganised as a state bank, issuing credit based solely on the needs of Japanese producers. From 1931–1941, Japanese industrial production rose 136% and the national income grew 241%. In Italy the state assumed control over the major banks through the Instituto Mobiliare Italiano in 1931. In 1936 Banking Law made the Bank of Italy the only bank for lending credit to other banks, removed limits on state borrowing, and removed Italy from the gold standard. Moreover it declared that the issuing of credit must serve the public. The Italian Social Republic took the ideas of profit sharing and worker co-management further during its short existence from 1943–1945, actively seeking to involve the common man in the control of industry with a program developed by former Communist Nicola Bombacci.

With the defeat of the Axis and the subsequent Cold War, Rightism, which had previously opposed liberalism in the economic as well as social spheres, became synonymous with Anglo-American free market policies, which played into the hands of debt finance. In regards to the origins of this supposed Capitalist versus Communist clash, Bolton also makes it clear that the Bolshevik revolution was welcomed by American financiers such as Jacob H. Schiff and John B. Young. Schiff himself financed The Friends of Russian Freedom, which spread revolutionary propaganda to Russian prisoners of war during the Russo-Japanese War.

The true reason for the financiers’ enmity against the Tsar was Russia’s refusal to cede sovereignty over its economy. The State Bank of the Russian Empire was under the control of the Ministry of Finance and it extended credit at minimal interest to Russian producers. Russia possessed large reserves of gold itself, so it had no need to borrow from the outside. For the most part the Tsarist economy was autarchic, beyond the grasp of international finance.

Against this false opposition between equally destructive ideologies of capitalism and communism, which have at their root atomized materialism, the real right stands for the superiority of spiritual values over profits. Bolton approvingly quotes Tsarist apologist George Knupffer, “We would feel certain that all of those who put the spirit above things material, duty above greed and love above hate and envy are in the camp of the Organic Right.” A fundamental premise of the economics of the true right must be the subordination of money to a higher cause, cultural good of a people. The people should not work to earn money to maintain their humdrum lives as cogs in the machinery of debt-finance, they should work for their greater glory. Communism and Capitalism are two sides of the same materialistic coin. As Spengler noted:

The concepts of Liberalism and Socialism are set in effective motion only by money. It was the Equites, the big-money party, which made Tiberius Gracchus’ popular movement possible at all; and as soon as that part of the reforms that were advantageous to themselves had been successfully legalized, they withdrew and the movement collapsed.

There is no proletarian, not even a communist, movement that has not operated in the interests of money, in the directions indicated by money, and for the time permitted by money — and that without the idealist amongst its leaders having the slightest suspicion of the fact.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries there were movements that fought both forms of materialism, as Bolton has chronicled in this book and others. While today’s Right devotes much time to issues of race and immigration, it is necessary to understand the economic origins of this increasingly rootless, atomized world we must fight. The Banking Swindle swerves as an excellent history of the movements that sought to break the bondage of interest and as primer on the true economics of the right. In this dark age of austerity, it illuminates a way forward for the nations under the heel of global finance, and one can only hope that it inspires the actions necessary for their liberation from these golden chains.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

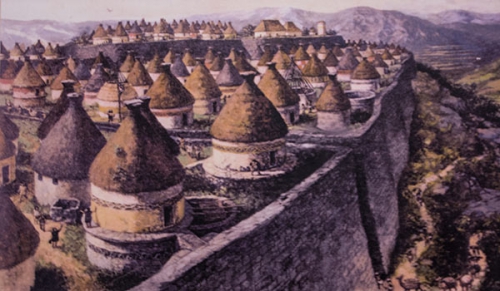

Holy crap! PBS has become America Unearthed. In an episode of the PBS series Secrets of the Dead running on local PBS stations this week and

Holy crap! PBS has become America Unearthed. In an episode of the PBS series Secrets of the Dead running on local PBS stations this week and  Griffhorn believes the Diodorus Siculus proves that the Carthaginians reached the Americas. Diodorus (Library of History 5.19-20) first describes an island, not a continent, “over against Libya”—meaning off the African coast—and states that it contains stately towns and fruitful plains when the Phoenicians discovered it:

Griffhorn believes the Diodorus Siculus proves that the Carthaginians reached the Americas. Diodorus (Library of History 5.19-20) first describes an island, not a continent, “over against Libya”—meaning off the African coast—and states that it contains stately towns and fruitful plains when the Phoenicians discovered it: He, of course, leaves out the information Diodorus—and, crucially, pseudo-Aristotle three centuries earlier, unacknowledged here—gave about the location of this mysterious island, which regular readers will of course remember quite well from when these same texts were used by

He, of course, leaves out the information Diodorus—and, crucially, pseudo-Aristotle three centuries earlier, unacknowledged here—gave about the location of this mysterious island, which regular readers will of course remember quite well from when these same texts were used by