Churchill, Hitler, and “the Unnecessary War”

How Britain Lost Its Empire and the West Lost the World

Patrick J. Buchanan

New York: Crown Publishers, 2008

Many reviewers of the respectable class become unhinged upon seeing the words “unnecessary war” in the title of a book dealing with World War II—in their minds, the “Good War” to destroy the ultimate evil of Hitler’s Nazism.[1] And, of course, Buchanan was already in deep kimchi on this issue since he had expressed a similar criticism of American entry into World War II in his A Republic, Not an Empire.[2]

With this mindset, most establishment reviewers simply proceed to write a diatribe against Buchanan for failing to recognize the allegedly obvious need to destroy Hitler, bringing up the Holocaust, anti-Semitism, and other rhetorical devices that effectively silence rational debate in America’s less-than-free intellectual milieu. However, Buchanan’s book is far more than a discussion of the merits of fighting World War II. For Buchanan is dealing with the overarching issue of the decline of the West—a topic he previously dealt with at length in his The Death of the West.[3] In his view, the “physical wounds” of World Wars I and II are significant factors in this decline. Buchanan writes: “The questions this book answers are huge but simple. Were these two world wars the mortal wounds we inflicted upon ourselves necessary wars? Or were they wars of choice? And if they were wars of choice, who plunged us into these hideous and suicidal world wars that advanced the death of our civilization? Who are the statesman responsible for the death of the West?” (p. xi). Early in his Introduction, Buchanan essentially answers that question: “Historians will look back on 1914–1918 and 1939–1945 as two phases of the Great Civil War of the West, when the once Christian nations of Europe fell upon one another with such savage abandon they brought down all their empires, brought an end to centuries of Western rule, and advanced the death of their civilization” (p. xvii).

Buchanan sees Britain as the key nation involved in this process of Western suicide. And its own fall from power was emblematic of the decline of the broader Western civilization. At the turn of the twentieth century, Britain stood out as the most powerful nation of the West, which in turn dominated the entire world. “Of all the empires of modernity,” Buchanan writes, “the British was the greatest—indeed, the greatest since Rome—encompassing a fourth of the Earth’s surface and people” (p. xiii). But Britain was fundamentally responsible for turning two localized European wars into the World Wars that shattered Western civilization.

Contrary to the carping of his critics, Buchanan does not fabricate his historical facts and opinions but rather relies on reputable historians for his information, which is heavily footnoted. In fact, most of his points should not be controversial to people who are familiar with the history of the period, as shocking as it may be to members of the quarter-educated punditocracy.

Buchanan points out that at the onset of the European war in August 1914, most of the British Parliament and Cabinet were opposed to entering the conflict. Only Foreign Minister Edward Grey and Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, held that it was necessary to back France militarily in order to prevent Germany from becoming the dominant power on the Continent. In 1906, however, Grey had secretly promised France support in the event of a war with Germany, which, Buchanan implies, might have served to encourage French belligerency in 1914. However, it was only the German invasion of neutral Belgium—the “rape” of “little Belgium” as pro-war propagandists bellowed—that galvanized a majority in the Cabinet and in Parliament for war.

Buchanan maintains that a victorious Germany, even with the expanded war aims put forth after the onset of the war, would not have posed a serious threat to Britain. And certainly it would have been better than the battered Europe that emerged from World War I. Describing the possible alternate outcome, Buchanan writes:

Germany, as the most powerful nation in Europe, aligned with a free Poland that owed its existence to Germany, would have been the western bulwark against any Russian drive into Europe. There would have been no Hitler and no Stalin. Other evils would have arisen, but how could the first half of the twentieth century have produced more evil than it did? (p. 62)

As it was, the four year world war led to the death of millions, with millions more seriously wounded. The utter destruction and sense of hopelessness caused by the war led to the rise of Communism. And the peace ending the war punished Germany and other members of the Central powers, setting the stage for future conflict. The Allies “scourged Germany and disposed her of territory, industry, people, colonies, money, and honor by forcing her to sign the ‘War Guilt Lie’” (p. 97). Buchanan acknowledges that it was not literally the “Carthaginian peace” that its critics charged. Germany “was still alive, more united, more populous and potentially powerful than France, and her people were now possessed of a burning sense of betrayal” (p. 97). But by making the new democratic German government accept the peace treaty, the Allies had destroyed the image of democratic government in Germany among the German people. In essence, the peace left “Europe divided between satiated powers, and revisionist powers determined to retrieve the lands and peoples that had been taken from them” (p. 95). It was “not only an unjust but an unsustainable peace. Wedged between a brooding Bolshevik Russia and a humiliated Germany were six new nations: Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Czechoslovakia. The last two held five million Germans captive. Against each of the six, Russia or Germany held a grievance. Yet none could defend its independence against a resurrected Germany or a revived Russia. Should Russia and Germany unite, no force on Earth could save the six” (p. 98). It should be noted that Buchanan’s negative depiction of the World War I peace is quite conventional, and was held by most liberal thinkers of the time.[4]

Buchanan likewise provides a very conventional interpretation of British foreign policy during the interwar period, which oscillated between idealism and Realpolitik and ultimately had the effect of weakening Britain’s position in the world. Buchanan points out that Britain needed the support of Japan, Italy, and the United States to counter a revived Germany, but its diplomacy undercut such an alliance. To begin with, Britain terminated its alliance with Japan to placate the United States as part of the Washington Naval Conference of 1922. Buchanan contends that the Japanese alliance had not only provided Britain with a powerful ally but served to restrain Japanese expansionism.

Britain needed Mussolini’s Italy to check German revanchism in Europe, a task which “Il Duce” was very willing to undertake. However, Britain drove Mussolini into the arms of Hitler by supporting the League of Nations’ sanctions against Italy after it attacked Ethiopia in 1935. “By assuming the moral high ground to condemn a land grab in Africa, not unlike those Britain had been conducting for centuries, Britain lost Italy,” Buchanan observes. “Her diplomacy had created yet another enemy. And this one sat astride the Mediterranean sea lanes critical in the defense of Britain’s Far Eastern empire against that other alienated ally, Japan” ( p. 155).

America, disillusioned by the war’s outcome, returned to its traditional non-interventionism in the 1920s, so it was not available to back British interests. Consequently, Britain would only have France to counter Hitler’s expansionism in the second half of the 1930s.

Buchanan provides a straightforward account of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s and Foreign Minister Halifax’s appeasement policy. The goal was to rectify the wrongs of Versailles so as to prevent the outbreak of war. “They believed,” Buchanan points out, “that addressing Germany’s valid grievances and escorting her back into Europe as a Great Power with equality of rights was the path to the peace they wished to build” (p. 201). Buchanan asserts that such a policy probably would have worked with democratic Weimar Germany, but not with Hitler’s regime, because of its insatiable demands and brutality.

Munich was the high point of appeasement and is conventionally considered one of the great disasters of British foreign policy. Buchanan explains Chamberlain’s reasoning for the policy, which was quite understandable. First, morality seemed to be on Germany’s side since the predominantly German population of the Sudetenland wanted to join Germany. Moreover, maintaining the current boundaries of Czechoslovakia was not a key British interest worth the cost of British lives. Finally, Britain did not have the wherewithal to intervene militarily in such a distant, land-locked country.

Churchill, who represented the minority of Britons who sought war as an alternative, believed that support from Stalinist Russia would serve to counter Hitler. Of course, as Buchanan points out, the morality of such an alliance was highly dubious because Stalin had caused the deaths of millions of people during the 1930s, while Hitler’s victims still numbered in the hundreds or low thousands before the start of the war in 1939. Moreover, Communist Russia would have to traverse Rumania and Poland to defend Czechoslovakia, and the governments of these two countries were adamantly opposed to allowing Soviet armies passage, correctly realizing that those troops would likely remain in their lands and bring about their Sovietization. It should also be added that it was questionable whether the Soviet Union really intended to make war on the side of the Western democracies, because Stalin hoped that a great war among the capitalist states, analogous to World War I, would bring about their exhaustion and facilitate the triumph of Communist revolution, aided by the intervention of the Soviet Red Army.[5]

Buchanan concludes that Chamberlain was right not to fight over the Sudetenland but “was wrong in believing that by surrendering it to Hitler he had bought anything but time,” which he should have used to rearm Britain in preparation for an inevitable war (p. 235). Instead, Chamberlain believed that Hitler could be trusted and that peace would prevail.

While Buchanan faults Chamberlain for not properly preparing for war after the Munich Agreement, he does not believe that Munich per se brought on the debacle of war. What did bring about World War II, according to Buchanan, was the British guarantee to defend Poland in March 1939. This guarantee made Poland more resistant to compromise with Germany, and made any British decision for war hinge on the decisions made by Poland. Moreover, as Buchanan points out, “Britain had no vital interest in Eastern Europe to justify a war to the death with Germany and no ability to wage war there” (p. 263).

Buchanan, while citing several explanations for the Polish guarantee, seems to give special credence to the view that Chamberlain was more of a realist than a bewildered naïf. Buchanan holds that a clear analysis of Chamberlain’s words and intent shows that in the guarantee the Prime Minister had not bound Britain to fight for the territorial integrity of Poland but only for its independence as a nation. “The British war guarantee,” Buchanan contends, “had not been crafted to give Britain a pretext for war, but to give Chamberlain leverage to persuade the Poles to give Danzig back” (p. 270). Chamberlain seemed to be “signaling his willingness for a second Munich, where Poland would cede Danzig and provide a road-and-rail route across the Corridor, but in return for Hitler’s guarantee of Poland’s independence” (p. 270). Hitler, however, did not grasp this “diplomatic subtlety” and believed that a German effort to take any Polish territory would mean war. The Poles did not understand Chamberlain’s intent either, and assumed that Britain would back their intransigence and thus refused to discuss any territorial changes with Germany. Buchanan, however, seems to reverse this interpretation of Chamberlain’s motivation when discussing his guarantees to other European countries in 1939, writing that “Chamberlain had lost touch with reality” (p. 278).

In the end, Britain and France went to war with Germany over Poland without the means to defend her. Poland’s fate was finally sealed when Hitler made his deal with Stalin in August 1939, which, in a secret protocol, offered the Soviet dictator the extensive territory that he sought in Eastern Europe.

Some reviewers have claimed that Buchanan excuses Hitler of blame for the war, but this is far from the truth. Buchanan actually states that Hitler bore “full moral responsibility” for the war on Poland in 1939 (p. 292), in contradistinction to the wider world war, though even here the charge of “full responsibility” would seem to be belied by much of the information in the book. For Buchanan points out that the Germans not only had justified grievances regarding the Versailles territorial settlement, but that, despite Hitler’s bold demands, the German-Polish war might not have happened without Britain’s meddling in 1939. Buchanan’s analysis certainly does not absolve Hitler of moral responsibility for the Second World War (much less palliate his crimes against humanity), but it does show that there is plenty of blame to go around.

Buchanan writes that “had there been no war guarantee, Poland . . . might have done a deal over Danzig and been spared six million dead” (p. 293). It is quite possible that after any territorial deal with Poland, Hitler would have consequently made much greater demands against her. Perhaps he would have acted no differently toward Poland and the Polish Jews than he actually did—but the outcome could not have been worse for the Polish Jews, almost all of whom were exterminated during the World War II. And Polish gentiles suffered far more than the inhabitants of other countries that resisted Hitler less strenuously. In short, a war purportedly to defend Poland was an utter disaster for the inhabitants of Poland. It is hardly outrageous to question whether this was the best possible outcome and to attempt to envision a better alternative.

Buchanan shows how World War II was hardly a “Good War.” The Allies committed extreme atrocities such as the deliberate mass bombing of civilians and genocidal population expulsions. The result was the enslavement of half of Europe by Soviet Communism. “To Churchill,” Buchanan writes, “the independence and freedom of one hundred million Christian peoples of Eastern Europe were not worth a war with Russia in 1945. Why, then, had they been worth a war with Germany in 1939?” (p. 373).

Buchanan holds that had Britain not gone to war against Germany, a war between Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany would have been inevitable, and that such a conflict would have exhausted both dictatorships, making it nigh impossible for either of them to conquer Western Europe. Although this scenario would not have been a certainty, a military stalemate between the two totalitarian behemoths would seem to be the most realistic assessment based on the actual outcome of World War II. Certainly, the Soviet Union relied on Western support to defeat the Nazi armies; and Germany was unable to knock out the Soviet Union during the lengthy period before American military began to play a significant role in Europe.

Buchanan contrasts the lengthy wars fought by Britain, which gravely weakened it, and the relative avoidance of war by the United States, which enabled it to become the world’s greatest superpower. In Buchanan’s view, the United States “won the Cold War—by avoiding the blunders Britain made that plunged her into two world wars” (p. 419). In the post-Cold War era, however, the United States has ignored this crucial lesson, instead becoming involved in unnecessary, enervating wars. “America is overextended as the British Empire of 1939,” Buchanan opines. “We have commitments to fight on behalf of scores of nations that have nothing to do with our vital interests, commitments we could not honor were several to be called in at once” (p. 423). Buchanan maintains that in continuing along this road the United States will come to the same ruinous end as Britain.

Buchanan’s British analogy, unfortunately, can be seen as giving too much to the position of the current neo-conservative war party. Although I think Buchanan’s non-interventionist position on the World Wars is correct, it should be acknowledged that Britain faced difficult choices. Allowing Germany to become the dominant power on the Continent would have been harmful to British interests—though the two World Wars made things even worse. In contrast, today it is hard to see any serious negative consequences resulting from the United States’ pursuit of a peaceful policy in the Middle East. No Middle East country or terrorist group possesses (or possessed) military power in any way comparable to that of Germany under the Second or Third Reichs, and, at least, Iran and Iraq do (did) not have any real interest in turning off the oil spigot to the West since selling oil is the lifeblood of their economies.

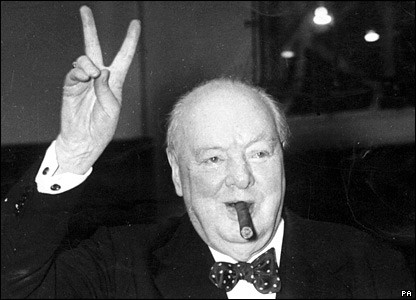

Another important aspect of the book is Buchanan’s attack on the cult of Winston Churchill, who has served as a role model for America’s recent bellicose foreign policy, with President George W. Bush even placing a bust of Churchill in the Oval Office. Buchanan maintains that Churchill, with his lust for war, was the individual most responsible for the two devastating World Wars.

In contrast to the current Churchill hagiography, Buchanan portrays the “British Bulldog” as a poor military strategist who was ruthlessly indifferent to the loss of human life, advocating policies that could easily be labeled war crimes. Churchill proposed both the incompetent effort to breech the Dardanelles in 1915, ending with the disastrous Gallipolli invasion, and the bungled Norwegian campaign of April 1940. Ironically, the failures of the Norwegian venture caused the downfall of the Chamberlain government and brought Churchill to power on May 10, 1940.

Churchill supported the naval blockade of Germany in World War I, which in addition to stopping war materiel prevented food shipments, causing an estimated 750,000 civilian deaths. Churchill admitted that the purpose of the blockade was to “starve the whole population—men, women, and children, old and young, wounded and sound—into submission” (p. 391). He successfully proposed the use of poisonous gas against Iraqi rebels in the interwar period and likewise sought the use of poison gas against German civilians in World War II, though the plan was not implemented due to opposition from the British military. Churchill was, however, successful in initiating the policy of intentionally bombing civilians, which caused the deaths of hundreds of thousands. Equally, if not more, inhumane, Churchill’s support for the forcible “repatriation” of Soviet POWs to the Soviet Union and the “ethnic cleansing” of Germans from Eastern and Central Europe involved the deaths of millions of people. And, of course, Churchill was willing to turn over Eastern Europe’s millions to slavery and death under Stalinist rule.

Overall, the Buchanan thesis makes considerable sense—though in some cases it assumes a foresight that would not be possible. For example, the pursuit of containment by the United States in the Cold War period, which Buchanan praises, was a policy largely rejected by the contemporary American Right, of which Buchanan was a member. The American Right held that the policy of containment was a defensive policy that could not achieve victory but instead likely lead to defeat—a position best expressed by James Burnham. And, at least up until Reagan’s presidency, the power of the Soviet Union greatly increased, both in terms of its nuclear arsenal and its global stretch, relative to that of the United States. While Buchanan touts Reagan’s avoidance of war, what most distinguished Reagan from his presidential predecessors and the foreign policy establishment was his willingness to take a harder stance toward the Soviets—a difference that terrified liberals of the time. Reagan’s hard-line stance consisted of a massive arms build-up, and, more importantly, an offensive military strategy (violating the policy of containment), which had the United States supporting a revolt against the Soviet-controlled government in Afghanistan. (The policy was begun under President Carter but significantly expanded under Reagan.) Perhaps, if the United States had launched such a policy in the early years of the Cold War, the Soviet Empire would have unraveled much earlier and not been such a threat to the United States. The Soviet Union was obviously the first country that could destroy the United States, and it achieved this lethal potential during the policy of containment. To this reviewer, it does not seem inevitable that everything would have ultimately turned out for the best.

While Buchanan makes a good case that the two World Wars were deleterious to the West, it would seem that they were only one factor, and probably not the primary one, in bringing about the downfall of Western power—a decline that was observed by astute observers such as Oswald Spengler prior to 1914.[6] (Buchanan himself is not oblivious to these other factors but gives a prominent place to the wars.) Moreover, it is questionable if Britain would have retained its empire any longer than it did, even without the wars, given the spread of nationalism to the non-Western world and the latter’s greater rates of population increase compared to Europe. Also, the growing belief in the West of universal equality obviously militated against European rule over foreign peoples.

In sum, Buchanan’s work provides an excellent account of British diplomacy and European events during the crucial period of the two world wars, which have shaped the world in which we now live. It covers a host of issues and events that are relatively unknown to those who pose as today’s educated class, and does so in a very readable fashion. While this reviewer regards Buchanan’s theses as fundamentally sound, the work provides a fount of information even to those who would dispute its point of view.

Forthcoming in TOQ vol. 9, no. 1 (Spring 2009).

<!--[if !supportFootnotes]-->[1] The phrase “The Unnecessary War” is not placed in quotes on the paper jacket or on the hardback cover but is in quotes inside the book, including on the title page. This tends to make the meaning of the phrase unclear. (I owe this insight to Dr. Robert Hickson who has produced a review of this book, along with others, for Culture Wars, though I present a somewhat different take on the subject.) Buchanan quotes Churchill’s use of the phrase in his memoirs (p. xviii). Churchill wrote: “One day President Roosevelt told me that he was asking publicly for suggestions about what the war should be called. I said at once, ‘The Unnecessary War.’ There never was a war more easy to stop than that which has just wrecked what was left of the world from the previous struggle.” But Churchill meant that the war could have been avoided if the Western democracies had taken a harder line, while Buchanan supports, in the main, a softer approach for the periods leading up to both wars.

[2] Patrick J. Buchanan, A Republic, Not an Empire: Reclaiming America’s Destiny (Washington, D.C.: Regnery, 1999). See also Stephen J. Sniegoski, “Buchanan’s book and the Empire’s answer: Fahrenheit 451!” The Last Ditch, October 13, 1999, http://www.thornwalker.com/ditch/snieg7.htm.

[3] Patrick J. Buchanan, The Death of the West: How Dying Populations and Immigrant Invasions Imperil Our Country and Civilization (New York: Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press, 2002).

[4] One early critic was the well-known British economist, John Maynard Keynes, The Economic Consequences of the Peace (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Howe, 1920).

[5] Viktor Suvorov, Icebreaker: Who Started the Second World War? (New York: Viking Press, 1990); Viktor Suvorov, The Chief Culprit: Stalin’s Grand Design to Start World War II (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2008); R. C. Raack, Stalin’s Drive to the West, 1938–1945: The Origins of the Cold War (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995); R. C. Raack, “Stalin’s Role in the Coming of World War II,” World Affairs, vol. 158, no. 4 (Spring 1996), http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/raack.htm; James E. McSherry, Stalin, Hitler, and Europe: The Origins of World War II, 1933–1939 (Cleveland: World Pub. Co, 1968).

[6] Spengler had developed his thesis of the Decline of the West (Der Untergang des Abendlandes) before the onset of World War I, though the first volume was not published until 1918.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Veale introduces J. M. Spaight and his book “

Veale introduces J. M. Spaight and his book “