mercredi, 24 juillet 2024

La nostalgie américaine face au déclin américain

La nostalgie américaine face au déclin américain

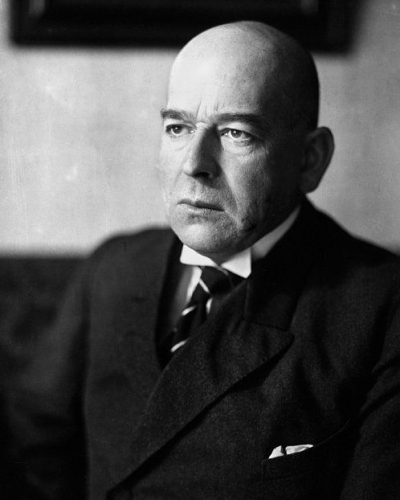

Constantin von Hoffmeister

Source: https://www.eurosiberia.net/p/american-nostalgia-in-decline?publication_id=1305515&post_id=146895779&isFreemail=true&r=jgt70&triedRedirect=true

Dans la mémoire collective des États-Unis, il subsiste une profonde nostalgie : celle de retrouver la gloire rayonnante à l'apogée de sa politique étrangère. C'était l'époque faste, marquée par la chute du mur de Berlin et l'essor triomphal des années 1990, où l'Amérique régnait en maître, en tant qu'hégémon mondial incontesté. C'était l'époque où les États-Unis, dotés d'une puissance inégalée, pouvaient faire plier la volonté du monde sans contrainte. La domination de la nation était inattaquable et son influence s'étendait à tous les coins du globe. La puissance américaine était une force de la nature, la preuve de l'exceptionnalisme du pays et l'incarnation de sa Destinée Manifeste. À cette époque, les États-Unis étaient souvent considérés comme la cité biblique de l'espoir, le parangon de la liberté et le garant de la stabilité mondiale, leur suprématie étant incontestée et leur avenir apparemment illimité.

Pourtant, ces jours heureux se sont évanouis dans les annales de l'histoire. L'Amérique se retrouve aujourd'hui prise au piège d'un monde de plus en plus multipolaire. La Chine, avec son économie en plein essor et ses capacités militaires qui progressent rapidement, est devenue un adversaire redoutable. Cette nouvelle réalité oblige les Américains à se rendre à l'évidence : ils ne peuvent plus imposer leur volonté en toute impunité, sans se soucier du problème pressant de la pénurie. Dans ce nouveau paysage, ils doivent faire des compromis judicieux et concentrer leurs énergies avec précision. Contrairement à la vision myope d'une grande partie de l'establishment américain en matière de politique étrangère, il est impératif que la nation se concentre sur l'Asie de l'Est et se désintéresse de l'Europe, qui doit rester seule et prospérer en tant qu'empire dont les valeurs remontent aux runes nordiques et à Charlemagne.

Le philosophe Oswald Spengler propose une analyse prémonitoire des cycles de civilisation, prévoyant le déclin inéluctable des puissances occidentales. Selon Spengler, les civilisations connaissent des périodes de croissance, d'apogée et d'effondrement, à l'instar des organismes vivants ou de la Joconde (d'après le film Fight Club). Dans ce contexte, la situation difficile dans laquelle se trouve actuellement l'Amérique peut être considérée comme faisant partie d'un schéma historique plus large. La force autrefois dominante, aujourd'hui aux prises avec des pressions internes et externes, reflète la nature cyclique des civilisations que Spengler a si méticuleusement décrite. Les souvenirs des empires passés peuvent être discernés dans les luttes de l'Amérique, ce qui suggère un besoin d'introspection et de réorientation stratégique pour éviter le sort des hégémons précédents.

Les théories de Spengler éclairent davantage les crises démographiques et culturelles qui minent les États-Unis. Selon lui, la baisse du taux de natalité et la lente stagnation de la vitalité culturelle signalent le crépuscule de l'influence d'une civilisation. Le dilemme démographique et le démantèlement des valeurs traditionnelles en Amérique peuvent donc être interprétés comme les signes d'un malaise plus profond, reflétant la vision de Spengler sur le déclin de l'Occident. Le défi consiste à inverser ces tendances par un réveil de la vigueur et une reconstitution démographique, afin d'éviter le déclin que Spengler jugeait presque inévitable.

De plus, l'Amérique est assiégée par une crise migratoire artificielle à l'intérieur de ses propres frontières. On estime qu'une proportion stupéfiante de dix pour cent de sa population est constituée d'étrangers en situation irrégulière, tandis que quinze autres pour cent sont plongés dans diverses formes d'ambiguïté juridique. La tâche herculéenne consistant à assimiler un si grand nombre de personnes dans la société - en veillant à ce qu'elles ne submergent pas les services de santé, les établissements d'enseignement et d'autres infrastructures vitales - est primordiale. Le fléau de la traite des êtres humains, du trafic de drogue et du trafic sexuel, exacerbé par la porosité de la frontière sud avec le Mexique, constitue un grave sujet de préoccupation.

Autrefois bastion d'une démographie saine parmi les nations occidentales, l'Amérique connaît aujourd'hui un sérieux déclin. La société américaine vieillit à un rythme alarmant. Le triste phénomène de l'augmentation des taux de suicide, en particulier chez les jeunes, associé à la diminution de l'espérance de vie, jette une ombre sur l'avenir de la nation. Dans de nombreux comtés du centre du pays, l'espérance de vie a chuté à des niveaux qui rappellent ceux de nombreuses nations du tiers-monde.

En outre, l'Amérique a systématiquement démantelé sa base industrielle en l'espace de trois décennies. Les conséquences de cette désindustrialisation sont multiples et désastreuses. Des communautés entières, autrefois animées par le bourdonnement de la fabrication et de l'industrie, languissent aujourd'hui dans la désolation et la décomposition. La disparition de ces industries a érodé les fondements économiques de la nation et rompu le tissu social qui unit les communautés.

La marche de la mondialisation, tout en enrichissant les coffres de l'élite, a laissé la classe ouvrière en ruines, privée de la dignité et de la raison d'être qu'apporte un travail digne de ce nom. Le fantôme du chômage et du sous-emploi hante le pays, une plaie silencieuse qui ronge l'âme de la nation.

La prolifération de la technologie, tout en annonçant une ère de commodité et de connectivité sans précédent, a également provoqué de profondes perturbations. L'automatisation et l'intelligence artificielle menacent de rendre obsolètes les compétences et le travail d'innombrables Américains, les jetant à la dérive dans une économie qui ne valorise plus leurs contributions.

L'assaut contre les valeurs traditionnelles et l'héritage culturel de la nation en a déconcerté plus d'un. Les piliers autrefois solides de la foi, de la famille et de la communauté ont été dévorés par les forces corrosives de la modernité, laissant un vide qui a été comblé par le nihilisme et le désespoir. Cette décadence culturelle a été exacerbée par la montée de la « woke culture », qui cherche à réécrire le récit de l'histoire américaine. Grâce à l'influence généralisée de plateformes médiatiques telles que Netflix, il existe une tendance omniprésente à falsifier l'histoire, souvent en occultant des événements et des personnages historiques pour les adapter aux programmes idéologiques contemporains. Ce révisionnisme ne déforme pas seulement le passé, il sape également l'héritage commun qui unissait autrefois la nation, aggravant encore le sentiment de dislocation et de désenchantement de ses habitants.

La convergence de ces crises - un flux migratoire écrasant, un déclin démographique brutal, une désindustrialisation implacable et la subversion insidieuse des valeurs culturelles - projette sur l'Amérique l'ombre d'un défi redoutable. Pourtant, c'est grâce à l'indomptable volonté faustienne du mouvement trumpiste qu'une voie vers le renouveau est visible, promettant de redresser la nation. Avec une détermination farouche à s'attaquer à ces questions multiformes, ce mouvement envisage une Amérique qui constitue un pôle majeur dans le concert multipolaire du monde, bien qu'elle soit plus isolationniste. Le chemin vers la résurgence est semé d'embûches, mais la vision d'une Amérique renouvelée, ferme et robuste, la pousse à aller de l'avant.

Renaître par la volonté : une Amérique forte dans un monde multipolaire.

20:47 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, états-unis, déclin américain |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 09 juillet 2022

La fin de la Pax Americana - De la chute d'un empire

La fin de la Pax Americana

De la chute d'un empire

Andreas Mölzer

Source: https://andreasmoelzer.wordpress.com/2022/07/08/das-ende-der-pax-americana/

C'est la tâche et le privilège de l'historien de diviser le déroulement des événements politiques, économiques et sociaux sur cette planète en époques, en périodes. Comme chacun sait, le court et terrible 20ème siècle a duré de 1914, date du début de la Première Guerre mondiale, à 1989, date de l'effondrement de l'empire soviétique. Ensuite, il n'y a pas eu de "fin de l'histoire" avec la victoire continue du système de valeurs occidental et de la démocratie à l'occidentale, mais sans aucun doute l'ère de la domination mondiale de la seule superpuissance restante, les États-Unis d'Amérique.

Cette période a duré trois bonnes décennies, jusqu'à l'éclatement de la guerre actuelle de la Russie contre l'Ukraine, qui est essentiellement un conflit entre le plus grand pays du monde, la Russie, et l'Occident dans son ensemble, représenté par le traité de l'Atlantique Nord. Au cours de cette période, qui a duré près d'un demi-siècle, les États-Unis ont pu imposer leurs intérêts politiques et militaires partout sur la planète et à tout moment - du moins en théorie.

Les tentatives de le faire n'ont pas manqué. Que ce soit avec le mandat des Nations unies ou non, avec des alliés de l'OTAN ou seuls, les États-Unis ont en tout cas mené au cours de cette période un nombre incalculable d'opérations militaires, plus ou moins importantes, qu'ils se sont arrogées dans leur rôle de seule superpuissance restante et de gendarme du monde. Que ce soit en Irak, en Afghanistan, en Somalie, dans les Balkans ou en Amérique latine, les Américains ont toujours agi dans l'intérêt de leur position de puissance mondiale et des besoins de leur économie. Bien entendu, ils ont toujours prétexté le maintien de la paix, des droits de l'homme et de la démocratie. La plupart du temps, ce n'était qu'un prétexte et presque toujours sans succès. En effet, dans la plupart des cas, les Américains ont opéré sans succès au cours des 40 dernières années. L'échec de l'opération militaire en Afghanistan et le retrait sans gloire des troupes américaines il y a un an en sont la dernière preuve.

Jusqu'en 1989, l'adversaire de l'Amérique dans la guerre froide était l'empire soviétique, dirigé par les maîtres russes du Kremlin. Après l'effondrement du socialisme réellement existant et du Pacte de Varsovie, la Fédération de Russie s'est également désintégrée et affaiblie dans les années 1990. De vastes zones de territoires dominés par la Russie, notamment en Europe de l'Est, sont tombées sous domination étrangère. Ce n'est que le déclin de la Russie à l'époque d'Eltsine qui a permis aux États-Unis d'asseoir leur domination mondiale.

Aujourd'hui, sous l'impulsion de Vladimir Poutine, la Russie s'est en quelque sorte redressée ces dernières années. Elle est redevenue un "acteur mondial" et a joué un rôle politique dans les conflits mondiaux, comme au Moyen-Orient. Avec l'éclatement de la guerre en Ukraine, il semble que les États-Unis jouent à nouveau un rôle dominant dans le cadre de l'OTAN et continuent de jouer le rôle de gendarme du monde, mais en réalité, les Européens en particulier sont à nouveau contraints de suivre le leadership politique et militaire des Américains. D'autre part, la Russie de Vladimir Poutine - qu'elle remporte ou non la guerre d'Ukraine - se positionne comme l'adversaire politique mondial des Américains. Alors que jusqu'à présent, on pouvait encore supposer une sorte de coexistence avec la superpuissance américaine, la Russie adopte à nouveau une position claire, frontale. Il existe donc à nouveau une sorte d'ordre mondial bipolaire.

Il semble que le facteur des pays BRICS, c'est-à-dire des pays comme le Brésil, la Russie, l'Inde, la Chine et, à l'avenir, l'Iran et d'autres pays, donne naissance à un ordre mondial multipolaire dans lequel les États-Unis ne sont plus qu'un facteur parmi d'autres. Reste à savoir si cet ordre mondial multipolaire sera également en mesure d'instaurer une stabilité globale, si une sorte d'équilibre des puissances pourra voir le jour. Ce qui est sûr, c'est que la pax americana, l'ordre mondial dominé par les États-Unis, touche à sa fin.

Les États-Unis restent toutefois la puissance économique dominante de la planète. L'industrie américaine, les multinationales dominées par les Américains dominent l'économie mondiale. Le potentiel d'innovation des États-Unis - la Silicon Valley, par exemple - reste le plus important au monde. Bien que le tissu social et le niveau d'éducation de la société américaine soient en déclin rapide, les États-Unis restent à la pointe en matière de nouveaux brevets et de développement technologique. Mais ceux qui connaissent l'état de l'infrastructure américaine savent que le pays reste en partie dans l'état d'un pays en développement.

Et sur le plan culturel, il faut certes reconnaître que les tendances mondiales de la mode, notamment les folies du politiquement correct, prennent leur source aux États-Unis. Mais en dehors de cela, le tissu socioculturel du pays est sur le point de s'effondrer. Cela est naturellement dû en premier lieu à l'immigration massive en provenance d'Amérique latine et à l'augmentation de la population de couleur.

La domination des Blancs protestants anglo-saxons est révolue depuis longtemps et les États-Unis risquent de devenir une entité multiculturelle dominée par la population de couleur et les Latinos. Ainsi, la "tiers-mondisation" des États-Unis se poursuit et le déclin de la première puissance économique mondiale s'accélère d'année en année.

Que les présidents républicains, comme récemment Donald Trump, lancent le slogan "Make America great again" et visent un cours plutôt isolationniste ou que les présidents démocrates tentent de reprendre le rôle de leader des Etats-Unis dans le monde, cela n'a finalement aucune importance. Le fait est que les États-Unis sont un pays qui connaît des problèmes et des conflits croissants, tant sur le plan économique que démographique et culturel. Mais cela rend obsolète la prétention de l'Amérique à rester la superpuissance dominante sur le plan mondial. De même, la prétention des Etats-Unis à ériger leur modèle politique et social en idéal mondial et à l'imposer autant que possible, si nécessaire par des moyens militaires, est également caduque.

Ainsi, l'empire américain n'est pas encore au bord de l'effondrement, mais sa prétention à la puissance est en grande partie caduque. D'une certaine manière, l'empire américain ressemble à son président actuel - il semble être frappé de sénilité. Il reste à voir dans quelle mesure les Européens seront en mesure d'utiliser la faiblesse croissante de l'empire américain pour renforcer leur propre position. Actuellement, ils sont absolument sous la domination du Pentagone et ne jouent qu'un rôle secondaire dans l'OTAN, tant sur le plan militaire que politique. Dans le conflit actuel avec la Russie, les pays de l'UE suivent plus ou moins à la lettre les directives américaines. L'espoir qui existait il y a une vingtaine d'années, à savoir que les Européens pourraient s'émanciper de la domination américaine au sein de l'OTAN et qu'une OTAN européanisée pourrait conduire à une politique de sécurité et de défense européenne propre, n'existe plus depuis longtemps.

Pourtant, il ne fait aucun doute que le déclin de l'empire américain devrait contraindre les Européens à développer leurs propres projets, notamment militaires. Même l'autodéfense de l'UE face à une Russie de plus en plus sûre d'elle et agressive serait difficile à l'heure actuelle sans les États-Unis. Si les Européens veulent jouer un rôle dans un ordre mondial multipolaire, ils devront devenir autonomes sur le plan de la politique de puissance et de la politique militaire, et devront également fournir des efforts de manière indépendante. De ce point de vue, le déclin de l'empire américain est une chance pour les Européens !

18:21 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : pax americana, états-unis, déclin américain, andreas mölzer, europe, affaires européennes, politique internationale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 24 novembre 2020

L'effondrement des Etats-Unis

L'effondrement des Etats-Unis

Concernant la Maison Blanche, le Président apparemment battu, Donald Trump, s'accroche au pouvoir et multiplie les décisions contradictoires. On l'a comparé à une grosse tortue sur le dos. Quant au Président élu, Joe Biden, surnommé Pappy Chaos, il s'agit d'un quasi vieillard, à la limite de la débilité psychique, sans lignes politiques précises, sauf à se vouloir le représentant d'une Amérique industrielle en voie de disparition. En fait les intérêts politiques qui le soutiennent chercheront à contrôler les discours, censurer les informations, mettre la main sur les activités culturelles. Son fils est réputé comme profondément corrompu et pourra grâce à la position de son père accroître encore les profits illicites dont il a toujours vécu.

L'affaire des fraudes électorales à grande échelle ayant accompagné voire provoqué l'élection de Joe Biden, a montré par ailleurs que l'Amérique considérée jusqu'alors comme une démocratie relativement exemplaire, se révèle l'égale des dictatures « modérées » que l'on trouve par dizaines dans le monde et où les élections n'ont que l'apparence de la démocratie électorale dont les Etats européens sont des modèles.

L'affaire des fraudes électorales à grande échelle ayant accompagné voire provoqué l'élection de Joe Biden, a montré par ailleurs que l'Amérique considérée jusqu'alors comme une démocratie relativement exemplaire, se révèle l'égale des dictatures « modérées » que l'on trouve par dizaines dans le monde et où les élections n'ont que l'apparence de la démocratie électorale dont les Etats européens sont des modèles.

Dans le domaine économique, les Etats-Unis accumulent actuellement les échecs. Le PIB stagne voire baisse dans certains domaines. La dette publique prend des proportions généralement qualifiées d'astronomiques et ne sera jamais remboursée, ceci au détriment de ceux qui jusqu'ici considéraient l'Etat américain comme un débiteur exemplaire. Ces difficultés sont aggravées par la crise due au coronavirus contre laquelle les Etats-Unis se montrent incapables de lutter efficacement, contrairement à la Chine, au Japon et à l'Europe. Il en résulte que le dollar en tant que monnaie de change internationale perd sans cesse des positions face au yen japonais et au yuhan chinois, voire face à l'euro.

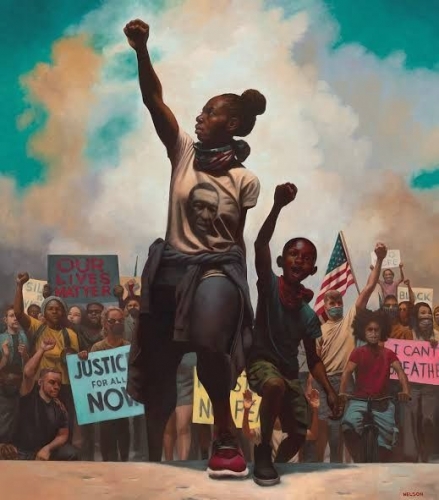

Par ailleurs, l'Amérique jusqu'ici, d'ailleurs à tort, considérée comme un modèle de coexistence pacifique entre les Blancs, les Noirs et les Asiatiques, apparaît désormais comme un théâtre permanent de conflits, de plus en plus armés, provoqués par des structures s'étant arrogé sans débat la responsabilité de défendre les intérêts respectifs des Noirs et des Blancs. Dans plusieurs villes, certaines organisations, notamment les Antifas se réclamant d'un antifascisme sommaire, ont tourné au gangstérisme, pillant les commerces et rendant la vie difficile dans de nombreux quartiers pour les Blancs ayant le seul tort que de n'être pas être Blacks.

On fera valoir, non sans raisons, que l'Amérique restera gouvernée par ce que l'on nomme l'Etat profond ou complexe militaro-industriel. Mais sera-ce un bien ? Les représentants de celui-ci, chefs d'entreprises et haut-gradés, ont pris en main depuis quelques années tous les centres de décision, depuis le Parlement jusqu'à la Maison-Blanche, sans mentionner les grandes administrations fédérales et les principaux médias. Le Département de la Justice, le FBI, la CIA et une vingtaine d'autres agences de renseignement peuvent désormais surveiller hors de tout contrôle parlementaire les citoyens américains et leurs activités.

Sur le plan militaire, l'Etat profond a accumulé les échecs et les reculs, notamment au Moyen Orient face à un Bachar al-Assad président de la Syrie et soutenu par la Russie. Il en est de même en Amérique Latine et en Afrique. Même dans l'Union européenne, notamment en Allemagne et en France, Angela Merkel et Emmanuel Macron ont pris les décisions nécessaires pour construire une défense européenne pouvant désormais se passer du « soutien » de l'US Army.

C'est seulement dans le domaine spatial, militaire ou civil, que les Etats Unis ont jusqu'ici conservé une incontestable « full spatial dominance ». Mais la Chine multiplie actuellement les investissements et les projets destinés à leur disputer cette domination.

21:31 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : états-unis, actualité, déclin américain, politique internationale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 07 novembre 2018

Le monde se dissocie discrètement des États-Unis

Le monde se dissocie discrètement des États-Unis

Traduit par le blog http://versouvaton.blogspot.fr

… et personne n’y prête attention

La confiance aveugle dans le dollar américain est peut-être l’un des facteurs les plus invalidants dont disposent les économistes pour évaluer notre avenir économique. Historiquement parlant, les monnaies fiduciaires sont des animaux dont la durée de vie est très courte, et les monnaies de réserve mondiales sont encore plus sujettes à une mort prématurée. Mais, pour une raison ou une autre, l’idée que le dollar est vulnérable au même sort est jugée ridicule par les médias dominants.

Des années avant que l’on ne soupçonne l’imminence d’une guerre commerciale, de nombreux pays ont établi des accords bilatéraux qui devaient réduire le dollar comme principal mécanisme d’échange. La Chine a été un chef de file dans cet effort, bien qu’elle soit l’un des plus importants acheteurs de titres du Trésor américain et détenteurs de réserves en dollars américains depuis le krach de 2008. Au cours des dernières années, ces accords bilatéraux ont pris de l’ampleur, en commençant par de petits accords, puis en se transformant en accords massifs sur les matières premières. La Chine et la Russie sont un parfait exemple de la tendance à la dé-dollarisation, les deux pays ayant formé une alliance commerciale sur le gaz naturel dès 2014. Cet accord, qui devrait commencer à stimuler les importations en Chine cette année, élimine le besoin de dollars comme mécanisme de réserve pour les achats internationaux.

La Russie et certaines parties de l’Europe, y compris l’Allemagne, se rapprochent également sur le plan commercial. Avec l’entrée de l’Allemagne et de la Russie dans l’accord sur le gazoduc Nordstream 2 malgré les condamnations de l’administration Trump, nous pouvons voir une nette progression des nations s’éloignant des États-Unis et du dollar et allant vers un « panier de devises ».

Le ministre de l’Énergie, Rick Perry, a laissé entendre que des sanctions sont possibles à l’égard du projet Nordstream 2, mais les politiques de guerre commerciale ne font que hâter le mouvement international qui s’écarte des États-Unis comme centre d’influence commerciale. Les sanctions américaines contre le pétrole iranien appuient cet argument, car la Chine, la Russie et une grande partie de l’Europe travaillent ensemble pour contourner les restrictions américaines sur le brut iranien.

La Chine a même mis en place son propre marché de pétro-yuans, et les premières livraisons de pétrole du Moyen-Orient vers la Chine payées par un contrat de pétro-yuans ont eu lieu en août de cette année. Les économistes classiques aiment à souligner la petite part du marché mondial du pétrole que représente le pétro-yuan, mais ils semblent ne pas avoir saisi l’ensemble de la situation. Le problème, c’est qu’il existe maintenant une solution de rechange au pétro-dollar là où il n’en existait pas auparavant. Et c’est là l’essentiel de la question qu’il faut examiner : La tendance vers des alternatives, et toutes les alternatives conduisant à la centralisation par les banques mondiales.

Au-delà de l’abandon du dollar américain en tant que monnaie de réserve mondiale, il y a une nouvelle question autour des systèmes de paiement internationaux alternatifs. SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication) est un réseau mondial de « messages financiers » entre les grandes banques, dont les banques centrales. Les transactions sont enregistrées via le réseau SWIFT, ce qui permet une confirmation rapide des « messages » et des mises à jour de comptes dans le monde entier.

Fondé à l’origine à Bruxelles, SWIFT est depuis des décennies le seul réseau bancaire de ce type disposant d’une capacité mondiale et, jusqu’à récemment, les principaux centres de données étaient situés aux États-Unis et aux Pays-Bas.

Le gouvernement américain a exploité un contrôle économique étendu en utilisant son influence sur SWIFT, notamment en surveillant massivement les transactions financières internationales et en refusant à des pays comme l’Iran l’accès à SWIFT par des sanctions. Par le passé, les États-Unis ont saisi ou gelé des fonds transférés par l’entremise de SWIFT entre des banques à l’extérieur des frontières américaines, y compris des transactions entièrement légales, ce qui indique que les États-Unis exercent un contrôle manifeste sur le système. Le statut de réserve mondiale du dollar, combiné à l’influence des États-Unis sur l’outil le plus important dans les transactions bancaires internationales, a renforcé la domination financière des États-Unis pendant de nombreuses années.

Mais le règne du dollar touche rapidement à sa fin, les banques mondiales comme le FMI cherchant à centraliser l’autorité monétaire dans une structure mondiale unique. La grande illusion perpétrée est que l’« ordre mondial multipolaire » qui est en train de naître est en quelque sorte « anti-globaliste ». Ce n’est tout simplement pas le cas.

Alors, que se passe-t-il réellement ? Le monde se rétrécit à mesure que tout le monde, SAUF les États-Unis, se consolide sur le plan économique. Cela inclut les alternatives à SWIFT.

La Russie vend ses bons du Trésor américain, mais entretient des liens étroits avec le FMI et la BRI, appelant à un système monétaire mondial sous le contrôle du FMI. La Chine fait de même, en resserrant ses liens avec le FMI par le biais de son système de panier de DTS, tout en coupant un par un ses liens avec le dollar. L’Europe se rapproche de la Russie et de la Chine, s’efforçant de défier les sanctions américaines.

Aujourd’hui, tous ces pays construisent de nouveaux réseaux de type SWIFT afin de mettre les États-Unis à l’écart de la boucle. En d’autres termes, les États-Unis sont en train de devenir le méchant de notre soap opera mondial et, du fait de leur orgueil démesuré, ils préparent le terrain pour leur propre destruction. Les États-Unis jouent un rôle de catalyseur en aidant les banques mondiales en faisant peur à leurs ennemis et alliés et en les poussant à une plus grande centralisation. Du moins, c’est le récit que je soupçonne que les futurs historiens reprendront.

Dans le cadre des efforts visant à saper les sanctions américaines contre le pétrole iranien, l’UE a établi un programme pour construire un nouveau système SWIFT en dehors de l’influence américaine. C’est un modèle auquel la Russie, la Chine et l’Iran ont accepté de participer, et la nouvelle a été largement ignorée par le grand public. Le Wall Street Journal a rapporté à contrecœur l’évolution de la situation, mais l’a rejetée comme étant inefficace pour contrecarrer les sanctions américaines. Et cela semble être le consensus parmi les médias – minimiser ou ignorer les implications d’un système SWIFT alternatif.

Les préjugés à l’égard du dollar soulèvent une fois de plus leur vilaine tête, et les dangers de ce genre de déni sont nombreux. Le dollar peut être, et est en train d’être contourné par des accords commerciaux bilatéraux. La domination américaine sur les marchés pétroliers est contournée par d’autres contrats pétroliers. Et maintenant, le contrôle américain des réseaux financiers est contourné par des programmes SWIFT alternatifs. Le seul fil conducteur qui maintient le dollar et, par extension, l’économie américaine ensemble est le fait que ces alternatives ne sont pas encore répandues. Cela va inévitablement changer.

Alors, la question est : quand cela va-t-il changer ?

Je crois que le rythme de la guerre commerciale dictera le rythme de la dé-dollarisation. Plus les tarifs deviendront agressifs entre les États-Unis et la Chine, l’Iran, l’Europe et la Russie, plus vite les systèmes alternatifs déjà existants seront mis en œuvre. À l’heure actuelle, la rapidité du conflit entre les États-Unis et la Chine laisse entrevoir un passage du dollar à un panier de monnaies internationales d’ici la fin 2020, et il faudra environ une autre décennie pour que ce processus se concrétise. En d’autres termes, le système du panier des DTS servira de pont dans le temps vers une nouvelle monnaie de réserve mondiale, un système monétaire mondial unique.Avec les tarifs douaniers actuels qui couvrent au moins la moitié du commerce chinois et l’autre moitié qui est menacée si la Chine riposte de quelque manière que ce soit, je pense que ce n’est qu’une question de mois avant que la Chine n’utilise ses propres dollars et réserves de bons du Trésor comme arme contre les États-Unis. Lorsque cela arrivera, la Chine n’annoncera pas publiquement cette mesure, et les grands médias ne sauteront dessus que beaucoup trop tard.

Ne vous attendez donc pas à ce que l’Europe vienne en aide à l’Amérique si cela se produit. Il me semble évident, d’après le comportement récent de l’UE, qu’elle a l’intention de rester neutre, du moins pendant l’escalade, si ce n’est être totalement du côté de la Chine et de la Russie par nécessité économique.

La préparation de cet événement exige autant d’indépendance financière que possible. Cela signifie des alternatives tangibles au dollar, comme les métaux précieux, et des économies localisées basées sur le troc et le commerce. Une fois que le dollar perdra son statut de réserve mondiale, le transfert de l’inflation des prix aux États-Unis sera immense. Les dollars détenus à l’étranger reviendront en masse dans le pays, car ils ne seront plus nécessaires à l’échange international de biens et de ressources. Ce changement pourrait se produire très rapidement, comme une avalanche.

Encore une fois, ne vous attendez pas à recevoir un avertissement avant que les créanciers étrangers ne vendent des actifs libellés en dollars, et attendez vous à ce que les effets négatifs se fassent sentir dans un délai très court sur Main Street.

Brandon Smith

Note du traducteur

Les analyses de cet auteur fortement anti-centralisation semblent parfois s'arrêter là où commencent les intérêts américains. Il est donc intéressant de connaître la vision d'un Américain pur jus, même anti-système, à l'égard de la fin de l'Empire américain. On pourrait le voir se réjouir de contempler la fin de l'Empire et de ces guerres impliquant le retour de la nation. Il devrait se féliciter de voir le dollar débarrassé de ce rôle de réserve mondiale qui désindustrialise son pays et lui vole sa souveraineté.

Certes les USA, s'ils existent encore en un seul morceau, devront faire défaut sur le dollar de la Fed et passer à une autre monnaie. Une monnaie souveraine ?

00:41 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, états-unis, déclin américain, dollar, économie, finance |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 23 avril 2014

The Ukraine Imbroglio and the Decline of the American Empire

The Ukraine Imbroglio and the Decline of the American Empire

When discussing the Ukraine-Crimea “crisis” it might be hygienic for Americans, including their political class, think-tank pundits, and talking heads, to recall two striking moments in “the dawn’s early light” of the U. S. Empire: in 1903, in the wake of the Spanish-American War, under President Theodore Roosevelt America seized control of the southern part of Guantanamo Bay by way of a Cuban-American Treaty which recognizes Cuba’s ultimate sovereignty over this base; a year after the Bolshevik Revolution, in 1918, President Woodrow Wilson dispatched 5,000 U. S. troops to Arkhangelsk in Northern Russia to participate in the Allied intervention in Russia’s Civil War, which raised the curtain on the First Cold War. Incidentally, in 1903 there was no Fidel Castro in Havana and in 1918 no Joseph Stalin in the Kremlin.

It might also be salutary to note that this standoff on Ukraine-Crimea is taking place in the unending afterglow of the Second Cold War and at a time when the sun is beginning to set on the American Empire as a new international system of multiple great powers emerges.

Of course, empires have ways of not only rising and thriving but of declining and expiring. It is one of Edward Gibbon’s insightful and challenging questions about the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire that is of particular relevance today. Gibbon eventually concluded that while the causes for Rome’s decline and ruin were being successfully probed and explicated, there remained the great puzzle as to why “it had subsisted for so long.” Indeed, the internal and external causes for this persistence are many and complex. But one aspect deserves special attention: the reliance on violence and war to slow down and delay the inevitable. In modern and contemporary times the European empires kept fighting not only among themselves, but also against the “new-caught, sullen peoples, half-devil and half-child,” once these dared to resist and eventually rise up against their imperial-colonial overlords. After 1945 in India and Kenya; in Indochina and Algeria; in Iran and Suez; in Congo. Needless to say, to this day the still-vigorous

U. S. empire and the fallen European empires lock arms in efforts to save what can be saved in the ex-colonial lands throughout the Greater Middle East, Africa, and Asia.

There is no denying that America’s uniquely informal empire, without settler colonies, expanded headlong across the globe during and following World War Two. It did so thanks to having been spared the enormous and horrid loss of life, material devastation, and economic ruin which befell all the other major belligerents, Allied and Axis. To boot, America’s mushrooming “military-industrial complex” overnight fired the Pax Americana’s momentarily unique martial, economic, and soft power.

By now the peculiar American Empire is past its apogee. Its economic, fiscal, social, civic, and cultural sinews are seriously fraying. At the same time the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) and Iran are claiming their place in the concert of world powers in which, for a good while, one and all will play by the rules of a new-model mercantilism in a globalizing soit-disant “free market” capitalist economy.

America’s splendid era of overseas “boots on the ground” and “regime change” is beginning to draw to a close. Even in the hegemonic sphere decreed by the Monroe Doctrine there is a world of difference between yesteryear’s and today’s interventions. In the not so distant good old times the U. S. horned in rather nakedly in Guatemala (1954), Cuba (1962), Dominican Republic (1965), Chile (1973), Nicaragua (1980s), Grenada (1983), Bolivia (1986), Panama (1989), and Haiti (2004), almost invariably without enthroning and empowering more democratic and socially progressive “regimes.” Presently Washington may be said to tread with considerably greater caution as it uses a panoply of crypto NGO-type agencies and agents in Venezuela. It does so because in every domain, except the military, the empire is not only vastly overextended but also because over the last few years left-leaning governments/“regimes” have emerged in five Latin American nations which most likely will become every less economically and diplomatically dependent on and fearful of the U. S.

Though largely subliminal, the greater the sense and fear of imperial decay and decline, the greater the national hubris and arrogance of power which cuts across party lines. To be sure, the tone and vocabulary in which neo-conservatives and right-of-center conservatives keep trumpeting America’s self-styled historically unique exceptionalism, grandeur, and indispensability is shriller than that of left-of-center “liberals” who, in the fray, tend to be afraid of their own shadow. Actually, Winston Churchill’s position and rhetoric is emblematic of conservatives and their fellow travelers in the epoch of the West’s imperial decline which overlapped with the rise and fall of the Soviet Union and Communism. Churchill was a fiery anti-Soviet and anti-Communist of the very first hour and became a discreet admirer of Mussolini and Franco before, in 1942, proclaiming loud and clear: “I have not become the King’s First Minister in order to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire.” By then Churchill had also long since become the chief crier of the ideologically fired “appeasement” mantra which was of one piece with his landmark “Iron Curtain” speech of March 1946. Needless to say, never a word about London and Paris, in the run-up to Munich, having willfully ignored or refused Moscow’s offer to collaborate on the Czech (Sudeten) issue. Nor did Churchill and his aficionados ever concede that the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact (Nazi-Soviet Pact) of August 1939 was sealed a year after the Munich Pact, and that both were equally infamous ideologically informed geopolitical and military chess moves.

To be sure, Stalin was an unspeakably cruel tyrant. But it was Hitler’s Nazi Germany that invaded and laid waste Soviet Russia through the corridor of Central and Eastern Europe, and it was the Red Army, not the armies of the Western allies, which at horrendous cost broke the spinal cord of the Wehrmacht. If the major nations of the European Union today hesitate to impose full-press economic sanctions on Moscow for its defiance on Crimea and Ukraine it is not only because of their likely disproportionate boomerang effect on them. The Western Powers, in particular Germany, have a Continental rather than Transatlantic recollection and narrative of Europe’s Second Thirty Years Crisis and War followed by the American-driven and –financed unrelenting Cold War against the “evil empire”—practically to this day.

During the reign of Nikita Khrushchev and Mikhail Gorbachev NATO, founded in 1949 and essentially led and financed by the U. S., inexorably pushed right up to or against Russia’s borders. This became most barefaced following 1989 to 1991, when Gorbachev freed the “captive nations” and signed on to the reunification of Germany. Between 1999 and 2009 all the liberated Eastern European countries—former Warsaw Pact members—bordering on Russia as well as three former Soviet republics were integrated into NATO, to eventually account for easily one-third of the 28 member nations of this North Atlantic military alliance. Alone Finland opted for a disarmed neutrality within first the Soviet and then post-Soviet Russian sphere. Almost overnight Finland was traduced not only for “appeasing” its neighboring nuclear superpower but also for being a dangerous role model for the rest of Europe and the then so-called Third World. Indeed, during the perpetual Cold War, in most of the “free world” the term and concept “Finlandization” became a cuss word well-nigh on a par with Communism, all the more so because it was embraced by those critics of the Cold War zealots who advocated a “third way” or “non-alignment.” All along, NATO, to wit Washington, intensely eyed both Georgia and Ukraine.

By March 2, 2014, the U. S. Department of State released a “statement on the situation in Ukraine by the North Atlantic Council” in which it declared that “Ukraine is a valued partner for NATO and a founding member of the Partnership for Peace . . . [and that] NATO Allies will continue to support Ukrainian sovereignty, independence, territorial integrity, and the right of the Ukrainian people to determine their own future, without outside interference.” The State Department also stressed that “in addition to its traditional defense of Allied nations, NATO leads the UN-mandated International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan and has ongoing missions in the Balkans and the Mediterranean; it also conducts extensive training exercises and offers security support to partners around the globe, including the European Union in particular but also the United Nations and the African Union.”

Within a matter of days following Putin’s monitory move NATO, notably President Obama, countered in kind: a guided-missile destroyer crossed the Bosphoros into the Black Sea for naval exercises with the Romanian and Bulgarian navies; additional F-15 fighter jets were dispatched to reinforce NATO patrol missions being flown over the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania; and a squadron of F-16 fighter bombers and a fulsome company of “boots on the ground” was hastened to Poland. Of course, theses deployments and reinforcements ostensibly were ordered at the urging of these NATO allies along Russia’s borders, all of whose “regimes” between the wars, and especially during the 1930s, had not exactly been paragons of democracy and because of their Russo-cum-anti-Communist phobia had moved closer to Nazi Germany. And once Hitler’s legions crashed into Russia through the borderlands not insignificant sectors of their political and civil societies were not exactly innocent by-standers or collaborators in Operation Barbarossa and the Judeocide.

To be sure, Secretary of State John Kerry, the Obama administration’s chief finger wagger, merely denounced Putin’s deployment in and around Ukraine-Crimea as an “act of aggression that is completely trumped up in terms of pretext.” For good measure he added, however, that “you just do not invade another country,” and he did so at a time there was nothing illegal about Putin’s move. But Hillary Clinton, Kerry’s predecessor, and most likely repeat candidate for the Democratic nomination for the Presidency, rather than outright demonize Putin as an unreconstructed KGB operative or a mini-Stalin went straight for the kill: “Now if this sounds familiar. . . it is like Hitler did back in the ‘30s.” Presently, as if to defang criticism of her verbal thrust, Clinton averred that “I just want people to have a little historic perspective,” so that they should learn from the Nazis’ tactics in the run-up to World War II.

As for Republican Senator John McCain, defeated by Barack Obama for the Presidency in 2008, he was on the same wavelength, in that he charged that his erstwhile rival’s “feckless” foreign policy practically invited Putin’s aggressive move, with the unspoken implication that President Obama was a latter-day Neville Chamberlain, the avatar of appeasement.

But ultimately it was Republican Senator Lindsey Graham who said out loud what was being whispered in so many corridors of the foreign policy establishment and on so many editorial boards of the mainline media. He advocated “creating a democratic noose around Putin’s Russia.” To this end Graham called for preparing the ground to make Georgia and Moldova members of NATO. Graham also advocated upgrading the military capability of the most “threatened” NATO members along Russia’s borders, along with an expansion of radar and missile defense systems. In short, he would “fly the NATO flag as strongly as I could around Putin”—in keeping with NATO’s policy since 1990. Assuming different roles, while Senator Graham kept up the hawkish drumbeat on the Hill and in the media Senator McCain hastened to Kiev to affirm the “other” America’s resolve, competence, and muscle as over the fecklessness of President Obama and his foreign-policy team. He went to Ukraine’s capital a first time in December, and the second time, in mid-March 2014, as head of a bipartisan delegation of eight like-minded Senators.

1990. Assuming different roles, while Senator Graham kept up the hawkish drumbeat on the Hill and in the media Senator McCain hastened to Kiev to affirm the “other” America’s resolve, competence, and muscle as over the fecklessness of President Obama and his foreign-policy team. He went to Ukraine’s capital a first time in December, and the second time, in mid-March 2014, as head of a bipartisan delegation of eight like-minded Senators.

On Kiev’s Maidan Square, or Independence Square, McCain not only mingled with and addressed the crowd of ardent anti-Russian nationalists, not a few of them neo-fascists, but also consorted with Victoria Nuland, U. S. Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs. Too much has been made of her revealing or unfortunate “fuck the EU” expletive in her tapped phone conversation with the local U. S. Ambassador Geoffrey Ryatt and her distribution of sweets on Maidan Square. What really matters is that Nuland is a consummate insider of Washington’s imperial foreign policy establishment in that she served in the Clinton and Bush administrations before coming on board the Obama administration, having close relations with Hillary Clinton.

Besides, she is married to Robert Kagan, a wizard of geopolitics who though generally viewed as a sworn neo-conservative is every bit as much at home as his spouse among mainline Republicans and Democrats. He was a foreign-policy advisor to John McCain and Mitt Romney during their presidential runs, respectively in 2008 and 2012, before President Obama let on that he embraced some of the main arguments in The World America Made (2012), Kagan’s latest book. In it he spells out ways to preserve the empire by way of controlling with some twelve naval task forces built around unsurpassable nuclear-powered aircraft carriers, its expanding Mare Nostrum in the South China Sea and Indian Ocean.

As a disciple of Alfred Thayer Mahan, quite naturally Kagan earned his spurs and his entrée to the inner circles of the makers and shakers of foreign and military policy by spending years at the Carnegie Endowment and Brookings Institution. That was before, in 1997, he became a co-founder, with William Kristol, of the neo-conservative Project for the New American Century, committed to the promotion of America’s “global leadership” in pursuit of its national security and interests. A few years later, after this think tank expired, Kagan and Kristol began to play a leading role in the Foreign Policy Initiative, its lineal ideological descendant.

But the point is not that Victoria Nuland’s demarche in Maidan Square may have been unduly influenced by her husband’s writings and political engagements. Indeed, on the Ukrainian question, she is more likely to have been attentive to Zbigniew Brzezinski, another highly visible geopolitician who, however, has been swimming exclusively in Democratic waters ever since 1960, when he advised John F. Kennedy during his presidential campaign and then became national security advisor to President Jimmy Carter. Heavily fixed on Eurasia, Brzezinski is more likely to stand on Clausewitz’s rather than Mahan’s shoulders. But both Kagan and Brzezinski are red-blooded imperial Americans. In 1997, in his The Great Chessboard Brzezinski argued that “the struggle for global primacy [would] continue to be played” on the Eurasian “chessboard,” and that as a “new and important space on [this] chessboard . . . Ukraine was a geopolitical pivot because its very existence as an independent country helps to transform Russia.” Indeed, “if Moscow regains control over Ukraine, with its [then] 52 million people and major resources, as well as access to the Black Sea,” Russia would “automatically again regain the wherewithal to become a powerful imperial state, spanning Europe and Asia.” The unwritten script of Brzezinski, one of Obama’s foreign policy advisors: intensify the West’s—America’s—efforts, by means fair and foul, to detach Ukraine from the Russian sphere of influence, including especially the Black Sea Peninsula with its access to the Eastern Mediterranean via the Aegean Sea.

Presently rather than focus on the geopolitical springs and objectives of Russia’s “aggression” against Ukraine-Crimea Brzezinski turned the spotlight on the nefarious intentions and methods of Putin’s move on the Great Chessboard. To permit Putin to have his way in Ukraine-Crimea would be “similar to the two phases of Hitler’s seizure of Sudetenland after Munich in 1938 and the final occupation of Prague and Czechoslovakia in early 1938.” Incontrovertibly “much depends on how clearly the West conveys to the dictator in the Kremlin—a partially comical imitation of Mussolini and a more menacing reminder of Hitler—that NATO cannot be passive if war erupts in Europe.” For should Ukraine be “crushed with the West simply watching the new freedom and security of Romania, Poland, and the three Baltic republics would also be threatened.” Having resuscitated the domino theory, Brzezinski urged the West to “promptly recognize the current government of Ukraine legitimate” and assure it “privately . . . that the Ukrainian army can count on immediate and direct Western aid so as to enhance its defense capabilities.” At the same time “NATO forces . . . should be put on alert [and] high readiness for some immediate airlift to Europe of U. S. airborne units would be politically and militarily meaningful.” And as an afterthought Brzezinski suggested that along with “such efforts to avoid miscalculations that could lead to war” the West should reaffirm its “desire for a peaceful accommodation . . . [and] reassure Russia that it is not seeking to draw Ukraine into NATO or turn it against Russia.” Indeed, mirabile dictu, Brzezinski, like Henry Kissinger, his fellow geopolitician with a cold-war imperial mindset, adumbrated a form of Finlandization of Ukraine—but, needless to say, not of the other eastern border states—without, however, letting on that actually Sergey Lavrov, the Russian Foreign Minister, had recently made some such proposal.

Of course, the likes of Kagan, Brzezinski, and Kissinger keep mum about America’s inimitable hand in the “regime change” in Kiev which resulted in a government in which the ultra-nationalists and neo-fascists, who had been in the front lines on Maidan Square, are well represented.

Since critics of America’s subversive interventions tend to be dismissed as knee-jerk left-liberals wired to exaggerate their dark anti-democratic side it might help to listen to a voice which on this issue can hardly be suspect. Abraham Foxman, national director of the Anti-Defamation League and renowned inquisitor of anti-Semitism, concedes that “there is no doubt that Ukraine, like Croatia, was one of those places where local militias played a key role in the murder of thousands of Jews during World War II.” And anti-Semitism “having by no means disappeared from Ukraine . . . in recent months there have been a number of anti-Semitic incidents and there are at least two parties in Ukraine, Svoboda and Right Sector, that have within them some extreme nationalists and anti-Semites.”

But having said that, Foxman insists that it is “pure demagoguery and an effort to rationalize criminal behavior on the part of Russia to invoke the anti-Semitism ogre into the struggle in Ukraine, . . . for it is fair to say that there was more anti-Semitism manifest in the worldwide Occupy Wall Street movement than we have seen so far in the revolution taking place in Ukraine.” To be sure, Putin “plays the anti-Semitism card” much as he plays that of Moscow rushing to “protect ethnic Russians from alleged extremist Ukrainians.” Even at that, however, “it is, of course, reprehensible to suggest that Putin’s policies in Ukraine are anything akin to Nazi policies during World War II.” But then Foxman hastens to stress that it “is not absurd to evoke Hitler’s lie” about the plight of the Sudeten Germans as comparable to “exactly” what “Putin is saying and doing in Crimea” and therefore needs to be “condemned . . . as forcefully . . . as the world should have condemned the German move into the Sudetenland.”

Abraham Foxman’s tortured stance is consonant with that of American and Israeli hardliners who mean to contain and roll back a resurgent great-power Russia, as much in Syria and Iran as in its “near abroad” in Europe and Asia.

As if listening to Brzezinski and McCain, Washington is building up its forces in the Baltic states, especially Poland, with a view to give additional bite to sanctions. But this old-style intervention will cut little ice unless fully concerted, militarily and economically, with NATO’s weighty members, which seems unlikely. Of course, America has drones and weapons of mass destruction—but so does Russia.

In any case, for unreconstructed imperials, and for AIPAC, the crux of the matter is not Russia’s European “near abroad” but its reemergence in the Greater Middle East, presently in Syria and Iran, and this at a time when, according to Kagan, the Persian Gulf was paling in strategic and economic importance compared to the Asia-Pacific region where China is an awakening sleeping giant that even now is the globe’s second largest economy—over half the size of the U. S. economy—and the unreal third largest holder of America’s public debt—by far the largest foreign holder of U. S. Treasury bonds.

In sum, the unregenerate U. S. empire means to actively contain both Russia and China in the true-and-tried modus operandi, starting along and over Russia’s European “near abroad” and the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait connecting the South China Sea to the East China Sea.

Because of ever growing budgetary constraints Washington has long since complained about its major NATO partners dragging their financial and military feet. This fiscal squeeze will intensify exponentially with the pivoting to the Pacific which demands steeply rising “defense” expenditures unlikely to be shared by a NATO-like Asia-Pacific alliance. Although most likely there will be a cutback in bases in the Atlantic world, Europe, and the Middle East, with the geographic realignment of America’s global basing the money thus saved will be spent many times over on the reinforcement and expansion of an unrivaled fleet of a dozen task forces built around nuclear-powered aircraft carriers. After all, the Pacific and Indian oceans combined being easily more than twice the size of the Atlantic and though, according to Kagan, China is not quite yet an “existential threat” it is “developing one or two aircraft carriers, . . . anti-ship ballistic missiles . . . and submarines.” Even now there are some flashpoints comparable to Crimea, Baltic, Syria, and Iran: the dustup between Japan and China over control of the sea lanes and the air space over the potentially oil-rich South China Sea; and the Sino-Japanese face-off over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea. Whereas it is all but normal for Taiwan, Japan, the Philippines, and South Korea to have tensions, even conflictual relations, with China and North Korea, it is something radically different for the United States to NATOize them in the pursuit of its own imperial interest in the furthest reaches of its now contested Mare Nostrum.

The Pacific-Asian pivot will, of course, further overstretch the empire in a time of spiraling fiscal and budgetary constraints which reflect America’s smoldering systemic economic straits and social crisis, generative of growing political dysfunction and dissension. To be sure, rare and powerless are those in political and academic society who question the GLORIA PRO NATIONE: America the greatest, exceptional, necessary, and do-good nation determined to maintain the world’s strongest and up-to-date military and cyber power.

And therein lies the rub. The U.S.A. accounts for close to 40% of the world’s military expenditures, compared to some 10% by China and 5.5% by Russia. The Aerospace and Defense Industry contributes close to 3% oi GDP and is the single largest positive contributor to the nation’s balance of trade. America’s three largest arms companies—Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Boeing—are the world’s largest, employing some 400,000 hands, and all but corner the world’s market in their “products.” Of late defense contracting firms have grown by leaps and bounds in a nation-empire increasingly loathe to deploy conventional boots on the ground. These corporate contractors provide an ever greater ratio of contract support field personnel, many of them armed, over regular army personnel. Eventually, in Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan and Operation Iraqi Freedom private contract and regular military personnel were practically on a par.

This hasty evocation of the tip of America’s military iceberg is but a reminder of President Dwight Eisenhower’s forewarning, in 1961, of an “immense military establishment” in lockstep with “a large arms industry. . . [acquiring] unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought,” injurious to democracy. At the time Ike could hardly have imagined the gargantuan growth and political weight of this military-industrial complex or the emergence, within it, of a corporate-contract mercenary army.

The formidable oligarchy of arms makers and merchants at the heart of the military-industrial complex fields a vast army of lobbyists in Washington. In recent years the arms lobby, writ large, spent countless millions during successive election cycles, its contributions being all but equally divided between Democrats and Republicans. And this redoubtable octopus-like “third house” is not about to sign on to substantial cuts in military spending, all the less so since it moves in sync with other hefty defense-related lobbies, such as oil, which is not likely to support the down-sizing of America’s navy which, incidentally, is far and away the largest plying, nay patrolling, the world’s oceans—trade routes.

There is, of course, a considerable work force, including white-collar employees, that earns its daily bread in the bloated “defense” sector. It does so in an economy whose industrial/manufacturing sectors are shrinking, considerably because of outsourcing, most of it overseas. This twisted or peculiar federal budget and free-market economy not only spawn unemployment and underemployment but breed growing popular doubt about the material and psychic benefits of empire.

In 1967, when Martin Luther King, Jr., broke his silence on the war in Vietnam, he spoke directly to the interpenetration of domestic and foreign policy in that conflict. He considered this war an imperialist intervention in far-distant Southeast Asia at the expense of the “Great Society” which President Johnson, who escalated this war, proposed to foster at home. After lamenting the terrible sacrifice of life on both sides, King predicated that “a nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.” He even intimated that “there is nothing except a tragic death wish to prevent . . . the richest and most powerful nation in the world . . . from reordering our priorities, so that the pursuit of peace will take precedence over the pursuit of war.”

Almost 50 years later President Obama and his staff, as well as nearly all Democratic and Republican Senators and Representatives, policy wonks and pundits, remain confirmed and unquestioning imperials. Should any of them read Gibbon they would pay no mind to his hunch that “the decline of Rome was the natural and inevitable effect of immoderate greatness” which by blowback corroded the polity, society, and culture that carried it. Of course today, with no barbarians at the gates, there is no need for legions of ground forces so that the bankrupting “defense” budget is for a military of airplanes, ships, missiles, drones, cyber-weapons, and weapons of mass destruction. Si vis pacem para bellum—against whom and for which objectives?

In the midst of the Ukraine “crisis” President Obama flew to The Hague for the third meeting of the Nuclear Security Summit (NSS) chartered in 2010 to prevent nuclear terrorism around the world. The NSS was Obama’s idea and project, spelled out in an official statement issued by the White House Press Secretary on the eve of its founding meeting in April 2010 in Washington. This statement stressed that “over 2,000 tons of plutonium and highly enriched uranium exist in dozens of countries” and that there have been “18 documented cases of theft or loss of highly enriched uranium or plutonium.” But above all :”we know that al-Qaeda, and possibly other terrorist or criminal groups, are seeking nuclear weapons—as well as the materials and expertise needed to make them.” But the U. S., not being “the only country that would suffer from nuclear terrorism” and unable to “prevent it on its own,” the NSS means to “highlight the global threat” and take the urgently necessary preventive measures.

Conceived and established in the aftermath of 9/11, by the latest count the NSS rallies 83 nations bent on collaborating to head off this scourge by reducing the amount of vulnerable nuclear material worldwide and tightening security of all nuclear materials and radioactive sources in their respective countries. At The Hague, with a myriad of journalists covering the event, some 20 heads of state and government and some 5,000 delegates took stock of advances made thus far in this arduous mission and swore to press on. But there was a last minute dissonance. Sergey Lavrov, the Foreign Minister of Russia, and Yi Jinping, the President of China, along with 18 other chief delegates, refused to sign a declaration calling on member nations to admit inspectors of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to check on their measures to rein in the menace of nuclear terrorism.

Inevitably the standoff over Ukraine-Crimea dimmed, even overshadowed, the hoped-for éclat of the Nuclear Security Summit. President Obama’s mind was centered on an ad hoc session of the G 8 in the Dutch capital; a visit to NATO Headquarters in Brussels; an audience with Pope Francis at the Vatican, in Rome; and a hastily improvised meeting with King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia in Riyadh. Except for his visit with the Holy Father, from which he may have hoped to draw a touch of grace and indulgence, in his other meetings the President reasserted and proclaimed that America was and meant to remain what Hubert Védrine, a former French Foreign Minister, called the world’s sole “hyperpower.” The Ukraine-Crimea imbroglio merely gave this profession and affirmation a greater exigency.

It is ironical that the scheduled Nuclear Security Summit was the curtain-raiser for the President’s double-quick imperial round of improvised meetings in the dawn of what Paul Bracken, another embedded and experienced geopolitician, avers to be The Second Nuclear Age (2012), this one in a multipolar rather than bipolar world. Actually Bracken merely masterfully theorized what had long since become the guiding idea and practice throughout the foreign policy-cum-military establishment. Or, as Molière’s Monsieur Jourdain would put it, for many years the members of this establishment had been “speaking prose without even knowing it.”

The negotiated elimination or radical reduction of nuclear weapons is completely off the agenda. It is dismissed as a quixotic ideal in a world of nine nuclear powers: U. S., Russia, United Kingdom, France, China, India, Pakistan, North Korea—and Israel. It was on Obama’s watch that the U. S. and post-Soviet Russia agreed that neither would deploy more than roughly 1,500 warheads, down from many times that number. But now, with Russia’s reemergence as a great power and China’s prodigious forced-draft renascence, in a multipolar world the U. S. seems bent on keeping a considerable nuclear superiority over both. Whereas most likely Washington and Moscow are in the throes of “modernizing” their nuclear arsenals and delivery capabilities, in this sphere China is only beginning to play catch-up.

Standing tall on America’s as yet unsurpassed military and economic might, Obama managed to convince his partners in the G 8, the conspicuous but listless economic forum of the world’s leading economies, to suspend, not to say expel, Russia for Putin’s transgression in Ukraine-Crimea. Most likely, however, they agreed to make this largely symbolic gesture so as to avoid signing on to ever-stiffer sanctions on Moscow. With this American-orchestrated charade the remaining G 7 only further pointed up the prepossession of their exclusive club from which they cavalierly shut out the BRICS.

The decline of the American Empire, like that of all empires, promises to be at once gradual and relative. As for the causes of this decline, they are inextricably internal / domestic and external / foreign. There is no separating the refractory budgetary deficit and its attendant swelling political and social dissension from the irreducible military budget necessary to face down rival empires. Clearly, to borrow Chalmers Johnson’s inspired conceptually informed phrase, the “empire of bases,” with a network of well over 600 bases in probably over 100 countries, rather than fall overnight from omnipotence to impotence risks becoming increasingly erratic and intermittently violent in “defense” of the forever hallowed exceptional “nation.”

As yet there is no significant let-up in the pretension to remain first among would-be equals on the seas, in the air, in cyberspace, and in cyber-surveillance. And the heft of the military muscle for this supererogation is provided by a thriving defense industry in an economy plagued by deep-rooted unemployment and a society racked by a crying income and wealth inequality, growing poverty, creeping socio-cultural anomie, and humongous systemic political corruption. Notwithstanding the ravings of the imperial “Knownothings” these conditions will sap domestic support for an unreconstructed interventionist foreign and military policy. They will also hollow out America’s soft power by corroding the aura of the democratic, salvific, and capitalist City on the Hill.

Whereas the Soviet Union and communism were the polymorphic arch-enemy during the First Nuclear Age terrorism and Islamism bid well to take its place during the Second Nuclear Age. It would appear that the threat and use of nuclear weapons will be even less useful though hardly any less demonic today than yesterday. Sub specie aeternitatis the cry of the terrorist attack on New York’s World Trade Center and Boston’s Marathon was a bagatelle compared to the fury of the nuclear bombardment of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. It is, of course, commendable that so many nations now seek to prevent “nuclear terrorism” by way of the Nuclear Security Summit. However, there being no fail-safe systems of access control this endeavor is bound to be stillborn without a simultaneously resolute drive to radically reduce or liquidate the world’s staggering stock of nuclear weapons and weapons-grade nuclear materials. After all, the greater that stock the greater the opportunity and temptation for a terrorist, criminal, or whistle-blower to pass the Rubicon.

According to informed estimates presently there are well over 20,000 nuclear bombs on this planet, with America and Russia between them home to over 90% of them. No less formidable are the vast global stockpiles of enriched uranium and plutonium.

In September 2009 Obama adjured the U. N. Security Council that “new strategies and new approaches” were needed to face a “proliferation” of an unprecedented “scope and complexity,” in that “just one nuclear weapon exploded in a city—be it New York or Moscow, Tokyo or Beijing, London or Paris—could kill hundreds of thousands of people.” Hereafter it was not uncommon for Washington insiders to avow that they considered a domestic nuclear strike with an unthinkable dirty bomb a greater and more imminent security risk than a prosaic nuclear attack by Russia. All this while the Nuclear Security Summit was treading water and the Pentagon continues to upgrade America’s nuclear arsenal and delivery capabilities—with chemical weapons as a backstop. With the cutback of conventional military capabilities nuclear arms are not about to be mothballed.

Indeed, with this in mind the overreaction to Russia’s move in Ukraine-Crimea is disquieting. From the start the Obama administration unconscionably exaggerated and demonized Moscow’s—Putin’s—objectives and methods while proclaiming Washington’s consummate innocence in the unfolding imbroglio. Almost overnight, even before the overblown charge that Moscow was massing troops along Ukraine’s borders and more generally in Russia’s European “near abroad” NATO—i. e., Washington—began to ostentatiously send advanced military equipment to the Baltic counties and Poland. By April 4, 2014, the foreign ministers of the 28 member nations of NATO met in Brussels with a view to strengthen the military muscle and cooperation not only in the aforementioned countries but also in Moldova, Romania, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. In addition NATO air patrols would be stepped up while anti-missile batteries would be deployed in Poland and Romania. Apparently the emergency NATO summit also considered large-scale joint military exercises and the establishment of NATO military bases close to Russia’s borders which, according to Le Figaro, France’s conservative daily, would be “a demonstration of force which the Allies had themselves foregone during the years following the collapse of the Soviet Union.” Would tactical nuclear weapons and nuclear-capable aircraft—or nuclear-capable drones—be deployed on these bases?

To what end? In preparation of a conventional war of the trenches, Guderian-type armored operations or a total war of Operation Barbarossa variety? Of course, this being post Hiroshima and Nagasaki, there must be a backup or contingency plan for nuclear sword play, with both sides, should reciprocal deterrence fail, confident in their first and second strike capabilities. Not only Washington but Moscow knows that in 1945 the ultimate reason for using the absolute weapon was transparently geopolitical rather than purely military.

With the weight of the unregenerate imperials in the White House, Pentagon, Congress, the “third house,” and the think tanks there is the risk that this U. S.- masterminded NATO “operation freedom in Russia’s European “near abroad” will spin out of control, also because the American Knownothings are bound to have their Russian counterparts.

In this game of chicken on the edge of the nuclear cliff the U. S. cannot claim the moral and legal high ground since it was President Truman and his inner circle of advisors who unleashed the scourge of nuclear warfare, and with time there was neither an official nor a popular gesture of atonement for this wanton and excessive military excess. And this despite General Eisenhower’s eventual plaint that the “unleashing of the atomic infernos on mostly civilian populations was simply this: an act of supreme terrorism (emphasis added) . . . and of barbarity callously calculated by the U. S. planners to demonstrate their country’s demonic power to the rest of the world—and the Soviet Union in particular.” Is there a filiation between this cri de coeur and the forewarning about the toxicity of the “military industrial complex” in President Eisenhower’s farewell address?

This is a time for a national debate and a citizen-initiated referendum on whether or not the U. S. should adopt unilateral nuclear disarmament. It might be a salutary and exemplary exercise in participatory democracy.

Arno J. Mayer is emeritus professor of history at Princeton University. He is the author of The Furies: Violence and Terror in the French and Russian Revolutions and Plowshares Into Swords: From Zionism to Israel (Verso).

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : politique internationale, géopolitique, ukraine, europe, affaires européennes, russie, états-unis, déclin américain |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 22 octobre 2013

Conversations with History: Chalmers Johnson

00:04 Publié dans Actualité, Entretiens, Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : chalmers johnson, histoire, entretien, états-unis, déclin américain, impérialisme, impérialisme américain |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 21 octobre 2013

Chalmers Johnson

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Entretiens | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : chalmers johnson, états-unis, déclin américain |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 01 avril 2013

Les adieux au Greenback

«Les adieux au Greenback»

«Les USA pourraient, déjà dans un futur proche, se voir contraints d’amasser une réserve de yuans»

Ex: http://www.horizons-et-debats.ch/

Est-ce que la structure mondiale de la monnaie se trouve devant une refonte et un changement, comme nous ne l’avons plus vécu depuis de nombreuses décennies? Les spécialistes de monnaies en Europe voient et ressentent que particulièrement en Extrême-Orient «les adieux au Greenback» se font fortement entendre. Le chef du marché des changes d’une grande banque globale a nommé cela, lors d’une discussion, «le danger imminent de burnout». Des contournements de la monnaie de référence mondiale se sont établis notamment dans le commerce asiatique et l’économie pétrolière. Dans le commerce, les USA se retrouvent même derrière la Chine. Et toujours plus d’observateurs aux USA craignent un désastre à la suite de la politique monétaire ultra-libérale de la FED …

Un signe qui ne passe pas inaperçu: les pays émergents du bloc BRICS – soit le Brésil, la Russie, l’Inde, la Chine et l’Afrique du Sud – bricolent plus ou moins ouvertement à leur propre banque de développement. Capital de départ prévu: 50 milliards de dollars (!). Elle est clairement prévue – dans une phase ultérieure – comme concurrent possible au Fonds monétaire international, dans lequel les USA font la loi. La République populaire de Chine, de son côté, accélère davantage et plus ouvertement la propagation du yuan. Celui-ci a accédé rapidement, dans le commerce inter-asiatique, à un statut préférentiel de monnaie de facturation. En même temps, l’Europe est torturée par une douloureuse crise de dettes. Une récession menace de nouveau les USA après la baisse du produit intérieur brut lors du dernier trimestre de 2012. Mais la Chine a accédé, malgré moins de croissance, au rang de la plus grande nation de commerce mondial en 2012. Ainsi a-t-elle subtilisé, rapidement mais douloureusement, la couronne aux USA – que ceux-ci avaient portée depuis la Seconde Guerre mondiale …

Le magazine allemand Manager Magazin parle un langage clair: après des décennies, pendant lesquelles, au moyen de la mondialisation, de contrats stratégiques et de géants de Wall-Street en expansion, comme Coca-Cola, General Electric et IBM, la superpuissance USA a imposé son rythme au reste du monde, le vent tourne maintenant. Et ce tournant est dramatique. Dans le commerce mondial, surgit une nouvelle infrastructure, de plus en plus prête à renoncer à la monnaie de référence mondiale du dollar. «Les nouveaux joueurs de très haut niveau dans la ligue des champions économiques évoluant de façon rapide viennent d’Asie, d’Amérique latine, d’Afrique» …

Le Boston Consulting Group a établi, ces derniers jours, pour la cinquième fois depuis 2006, une liste des 100 plus grands challengers des pays émergents. Parmi les «100 Global Challengers», 30 viennent de Chine, 20 d’Inde. Pas moins de 1000 entreprises, venant des marchés émergents, ont franchi en 2006 le mur du son de 1 milliard de dollars de chiffre d’affaires annuel. L’analyse les nomme les Volkswagen, les Wal-Mart et les Apple de l’avenir! Ils sont maintenant sur le point de faire peur à l’Occident. Et la monnaie de référence mondiale pour les attaques sur le système économique mondial établi ne s’appelle plus automatiquement «dollar», mais de plus en plus souvent «renminbi». Les USA pourraient, déjà dans un futur proche, se voir contraints d’amasser une réserve de yuans, pour continuer à participer pleinement au commerce international …

La nervosité aux USA, face à cette relève de la garde, se transforme par endroits déjà en cynisme. «Nous voyons une guerre monétaire», dit Peter Schiff le PDG d’Euro Pacific Capital. «Ce qui distingue une guerre monétaire d’une autre guerre», ajoute-t-il, «c’est le fait que l’on se tue soi-même, et les USA semblent, dans ce sens-là, être déjà considérés comme le vainqueur désigné.»

Même pour le magnat des médias et milliardaire Steve Forbes, cela devient inquiétant: «La banque centrale américaine produit toujours plus de désastres, comme un drogué», dit-il, et il craint que la politique monétaire actuelle en arrive à ruiner l’économie américaine…

Source: Vertraulicher Schweizer Brief n° 1350 du 21/2/13

(Traduction Horizons et débats)

00:05 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : états-unis, politique internationale, chine, économie, devises, dollars, yuan, affaires asiatiques, asie, déclin américain |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 04 décembre 2011

The End of Americanism

The End of Americanism

Pat Buchanan's Suicide of a Superpower

Alex KURTAGIC

Ex: http://www.alternativeright.com

Pat Buchanan’s Suicide of a Superpower is an apt follow-up to his 2002 volume, The Death of the West. Although the new book focuses on the United States, it restates and updates the narrative of the older book. It is no coincidence, therefore, that the former refers briefly to the latter early on.

Buchanan’s main thesis is this:

When the faith dies, the culture dies, the civilization dies, the people die. That is the progression. And as the faith that gave birth to the West is dying in the West, peoples of European descent from the steppes of Russia to the coast of California have begun to die out, as the Third World treks north to claim the estate. The last decade provided corroborating if not conclusive proof that we are in the Indian summer of our civilization.