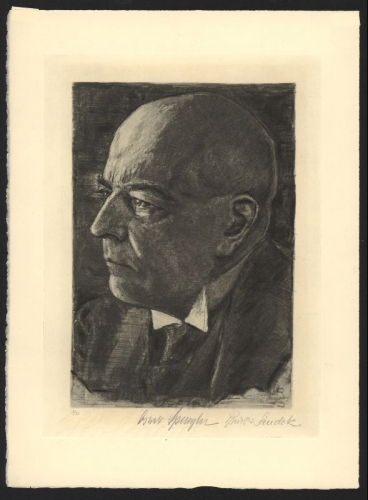

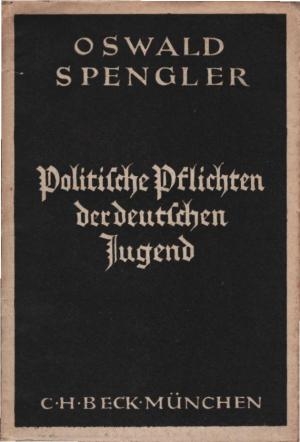

Oswald Spengler is by now well-known as one of the major thinkers of the German Conservative Revolution of the early 20th Century. In fact, he is frequently cited as having been one of the most determining intellectual influences on German Conservatism of the interwar period – along with Arthur Moeller van den Bruck and Ernst Jünger – to the point where his cultural pessimist philosophy is seen to be representative of Revolutionary Conservative views in general (although in reality most Revolutionary Conservatives held more optimistic views).[1]

To begin our discussion, we shall provide a brief overview of the major themes of Oswald Spengler’s philosophy.[2] According to Spengler, every High Culture has its own “soul” (this refers to the essential character of a Culture) and goes through predictable cycles of birth, growth, fulfillment, decline, and demise which resemble that of the life of a plant. To quote Spengler:

A Culture is born in the moment when a great soul awakens out of the proto-spirituality of ever-childish humanity, and detaches itself, a form from the formless, a bounded and mortal thing from the boundless and enduring. It blooms on the soil of an exactly-definable landscape, to which plant-wise it remains bound. It dies when the soul has actualized the full sum of its possibilities in the shape of peoples, languages, dogmas, arts, states, sciences, and reverts into the proto-soul.[3]

There is an important distinction in this theory between Kultur (“Culture”) and Zivilisation (“Civilization”). Kultur refers to the beginning phase of a High Culture which is marked by rural life, religiosity, vitality, will-to-power, and ascendant instincts, while Zivilisation refers to the later phase which is marked by urbanization, irreligion, purely rational intellect, mechanized life, and decadence. Although he acknowledged other High Cultures, Spengler focused particularly on three High Cultures which he distinguished and made comparisons between: the Magian, the Classical (Greco-Roman), and the present Western High Culture. He held the view that the West, which was in its later Zivilisation phase, would soon enter a final imperialistic and “Caesarist” stage – a stage which, according to Spengler, marks the final flash before the end of a High Culture.[4]

Perhaps Spengler’s most important contribution to the Conservative Revolution, however, was his theory of “Prussian Socialism,” which formed the basis of his view that conservatives and socialists should unite. In his work he argued that the Prussian character, which was the German character par excellence, was essentially socialist. For Spengler, true socialism was primarily a matter of ethics rather than economics. This ethical, Prussian socialism meant the development and practice of work ethic, discipline, obedience, a sense of duty to the greater good and the state, self-sacrifice, and the possibility of attaining any rank by talent. Prussian socialism was differentiated from Marxism and liberalism. Marxism was not true socialism because it was materialistic and based on class conflict, which stood in contrast with the Prussian ethics of the state. Also in contrast to Prussian socialism was liberalism and capitalism, which negated the idea of duty, practiced a “piracy principle,” and created the rule of money.[5]

Oswald Spengler’s theories of predictable culture cycles, of the separation between Kultur and Zivilisation, of the Western High Culture as being in a state of decline, and of a non-Marxist form of socialism, have all received a great deal of attention in early 20th Century Germany, and there is no doubt that they had influenced Right-wing thought at the time. However, it is often forgotten just how divergent the views of many Revolutionary Conservatives were from Spengler’s, even if they did study and draw from his theories, just as an overemphasis on Spenglerian theory in the Conservative Revolution has led many scholars to overlook the variety of other important influences on the German Right. Ironically, those who were influenced the most by Spengler – not only the German Revolutionary Conservatives, but also later the Traditionalists and the New Rightists – have mixed appreciation with critique. It is this reality which needs to be emphasized: the majority of Conservative intellectuals who have appreciated Spengler have simultaneously delivered the very significant message that Spengler’s philosophy needs to be viewed critically, and that as a whole it is not acceptable.

The most important critique of Spengler among the Revolutionary Conservative intellectuals was that made by Arthur Moeller van den Bruck.[6] Moeller agreed with certain basic ideas in Spengler’s work, including the division between Kultur and Zivilisation, with the idea of the decline of the Western Culture, and with his concept of socialism, which Moeller had already expressed in an earlier and somewhat different form in Der Preussische Stil (“The Prussian Style,” 1916).[7] However, Moeller resolutely rejected Spengler’s deterministic and fatalistic view of history, as well as the notion of destined culture cycles. Moeller asserted that history was essentially unpredictable and unfixed: “There is always a beginning (…) History is the story of that which is not calculated.”[8] Furthermore, he argued that history should not be seen as a “circle” (in Spengler’s manner) but rather a “spiral,” and a nation in decline could actually reverse its decline if certain psychological changes and events could take place within it.[9]

The most radical contradiction with Spengler made by Moeller van den Bruck was the rejection of Spengler’s cultural morphology, since Moeller believed that Germany could not even be classified as part of the “West,” but rather that it represented a distinct culture in its own right, one which even had more in common in spirit with Russia than with the “West,” and which was destined to rise while France and England fell.[10] However, we must note here that the notion that Germany is non-Western was not unique to Moeller, for Werner Sombart, Edgar Julius Jung, and Othmar Spann have all argued that Germans belonged to a very different cultural type from that of the Western nations, especially from the culture of the Anglo-Saxon world. For these authors, Germany represented a culture which was more oriented towards community, spirituality, and heroism, while the modern “West” was more oriented towards individualism, materialism, and capitalistic ethics. They further argued that any presence of Western characteristics in modern Germany was due to a recent poisoning of German culture by the West which the German people had a duty to overcome through sociocultural revolution.[11]

The most radical contradiction with Spengler made by Moeller van den Bruck was the rejection of Spengler’s cultural morphology, since Moeller believed that Germany could not even be classified as part of the “West,” but rather that it represented a distinct culture in its own right, one which even had more in common in spirit with Russia than with the “West,” and which was destined to rise while France and England fell.[10] However, we must note here that the notion that Germany is non-Western was not unique to Moeller, for Werner Sombart, Edgar Julius Jung, and Othmar Spann have all argued that Germans belonged to a very different cultural type from that of the Western nations, especially from the culture of the Anglo-Saxon world. For these authors, Germany represented a culture which was more oriented towards community, spirituality, and heroism, while the modern “West” was more oriented towards individualism, materialism, and capitalistic ethics. They further argued that any presence of Western characteristics in modern Germany was due to a recent poisoning of German culture by the West which the German people had a duty to overcome through sociocultural revolution.[11]

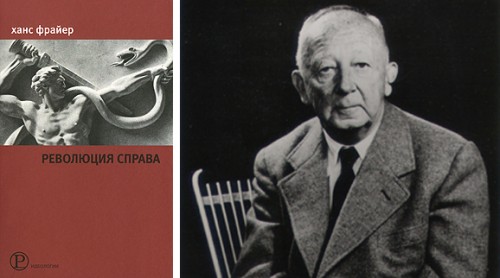

Another key intellectual of the German Conservative Revolution, Hans Freyer, also presented a critical analysis of Spenglerian philosophy.[12] Due to his view that that there is no certain and determined progress in history, Freyer agreed with Spengler’s rejection of the linear view of progress. Freyer’s philosophy of culture also emphasized cultural particularism and the disparity between peoples and cultures, which was why he agreed with Spengler in terms of the basic conception of cultures possessing a vital center and with the idea of each culture marking a particular kind of human being. Being a proponent of a community-oriented state socialism, Freyer found Spengler’s anti-individualist “Prussian socialism” to be agreeable. Throughout his works, Freyer had also discussed many of the same themes as Spengler – including the integrative function of war, hierarchies in society, the challenges of technological developments, cultural form and unity – but in a distinct manner oriented towards social theory.[13]

However, Freyer argued that the idea of historical (cultural) types and that cultures were the product of an essence which grew over time were already expressed in different forms long before Spengler in the works of Karl Lamprecht, Wilhelm Dilthey, and Hegel. It is also noteworthy that Freyer’s own sociology of cultural categories differed from Spengler’s morphology. In his earlier works, Freyer focused primarily on the nature of the cultures of particular peoples (Völker) rather than the broad High Cultures, whereas in his later works he stressed the interrelatedness of all the various European cultures across the millennia. Rejecting Spengler’s notion of cultures as being incommensurable, Freyer’s “history regarded modern Europe as composed of ‘layers’ of culture from the past, and Freyer was at pains to show that major historical cultures had grown by drawing upon the legacy of past cultures.”[14] Finally, rejecting Spengler’s historical determinism, Freyer had “warned his readers not to be ensnared by the powerful organic metaphors of the book [Der Untergang des Abendlandes] … The demands of the present and of the future could not be ‘deduced’ from insights into the patterns of culture … but were ultimately based on ‘the wager of action’ (das Wagnis der Tat).”[15]

However, Freyer argued that the idea of historical (cultural) types and that cultures were the product of an essence which grew over time were already expressed in different forms long before Spengler in the works of Karl Lamprecht, Wilhelm Dilthey, and Hegel. It is also noteworthy that Freyer’s own sociology of cultural categories differed from Spengler’s morphology. In his earlier works, Freyer focused primarily on the nature of the cultures of particular peoples (Völker) rather than the broad High Cultures, whereas in his later works he stressed the interrelatedness of all the various European cultures across the millennia. Rejecting Spengler’s notion of cultures as being incommensurable, Freyer’s “history regarded modern Europe as composed of ‘layers’ of culture from the past, and Freyer was at pains to show that major historical cultures had grown by drawing upon the legacy of past cultures.”[14] Finally, rejecting Spengler’s historical determinism, Freyer had “warned his readers not to be ensnared by the powerful organic metaphors of the book [Der Untergang des Abendlandes] … The demands of the present and of the future could not be ‘deduced’ from insights into the patterns of culture … but were ultimately based on ‘the wager of action’ (das Wagnis der Tat).”[15]

Yet another important Conservative critique of Spengler was made by the Italian Perennial Traditionalist philosopher Julius Evola, who was himself influenced by the Conservative Revolution but developed a very distinct line of thought. In his The Path of Cinnabar, Evola showed appreciation for Spengler’s philosophy, particularly in regards to the criticism of the modern rationalist and mechanized Zivilisation of the “West” and with the complete rejection of the idea of progress.[16] Some scholars, such as H.T. Hansen, stress the influence of Spengler’s thought on Evola’s thought, but it is important to remember that Evola’s cultural views differed significantly from Spengler’s due to Evola’s focus on what he viewed as the shifting role of a metaphysical Perennial Tradition across history as opposed to historically determined cultures.[17]

In his critique, Evola pointed out that one of the major flaws in Spengler’s thought was that he “lacked any understanding of metaphysics and transcendence, which embody the essence of each genuine Kultur.”[18] Spengler could analyze the nature of Zivilisation very well, but his irreligious views caused him to have little understanding of the higher spiritual forces which deeply affected human life and the nature of cultures, without which one cannot clearly grasp the defining characteristic of Kultur. As Robert Steuckers has pointed out, Evola also found Spengler’s analysis of Classical and Eastern cultures to be very flawed, particularly as a result of the “irrationalist” philosophical influences on Spengler: “Evola thinks this vitalism leads Spengler to say ‘things that make one blush’ about Buddhism, Taoism, Stoicism, and Greco-Roman civilization (which, for Spengler, is merely a civilization of ‘corporeity’).”[19] Also problematic for Evola was “Spengler’s valorization of ‘Faustian man,’ a figure born in the Age of Discovery, the Renaissance and humanism; by this temporal determination, Faustian man is carried towards horizontality rather than towards verticality.”[20]

Finally, we must make a note of the more recent reception of Spenglerian philosophy in the European New Right and Identitarianism: Oswald Spengler’s works have been studied and critiqued by nearly all major New Right and Identitarian intellectuals, including especially Alain de Benoist, Dominique Venner, Pierre Krebs, Guillaume Faye, Julien Freund, and Tomislav Sunic. The New Right view of Spenglerian theory is unique, but is also very much reminiscent of Revolutionary Conservative critiques of Moeller van den Bruck and Hans Freyer. Like Spengler and many other thinkers, New Right intellectuals also critique the “ideology of progress,” although it is significant that, unlike Spengler, they do not do this to accept a notion of rigid cycles in history nor to reject the existence of any progress. Rather, the New Right critique aims to repudiate the unbalanced notion of linear and inevitable progress which depreciates all past culture in favor of the present, while still recognizing that some positive progress does exist, which it advocates reconciling with traditional culture to achieve a more balanced cultural order.[21] Furthermore, addressing Spengler’s historical determinism, Alain de Benoist has written that “from Eduard Spranger to Theodor W. Adorno, the principal reproach directed at Spengler evidently refers to his ‘fatalism’ and to his ‘determinism.’ The question is to know up to what point man is prisoner of his own history. Up to what point can one no longer change his course?”[22]

Like their Revolutionary Conservative precursors, New Rightists reject any fatalist and determinist notion of history, and do not believe that any people is doomed to inevitable decline; “Decadence is therefore not an inescapable phenomenon, as Spengler wrongly thought,” wrote Pierre Krebs, echoing the thoughts of other authors.[23] While the New Rightists accept Spengler’s idea of Western decline, they have posed Europe and the West as two antagonistic entities. According to this new cultural philosophy, the genuine European culture is represented by numerous traditions rooted in the most ancient European cultures, and must be posed as incompatible with the modern “West,” which is the cultural emanation of early modern liberalism, egalitarianism, and individualism.

Like their Revolutionary Conservative precursors, New Rightists reject any fatalist and determinist notion of history, and do not believe that any people is doomed to inevitable decline; “Decadence is therefore not an inescapable phenomenon, as Spengler wrongly thought,” wrote Pierre Krebs, echoing the thoughts of other authors.[23] While the New Rightists accept Spengler’s idea of Western decline, they have posed Europe and the West as two antagonistic entities. According to this new cultural philosophy, the genuine European culture is represented by numerous traditions rooted in the most ancient European cultures, and must be posed as incompatible with the modern “West,” which is the cultural emanation of early modern liberalism, egalitarianism, and individualism.

The New Right may agree with Spengler that the “West” is undergoing decline, “but this original pessimism does not overshadow the purpose of the New Right: The West has encountered the ultimate phase of decadence, consequently we must definitively break with the Western civilization and recover the memory of a Europe liberated from the egalitarianisms…”[24] Thus, from the Identitarian perspective, the “West” is identified as a globalist and universalist entity which had harmed the identities of European and non-European peoples alike. In the same way that Revolutionary Conservatives had called for Germans to assert the rights and identity of their people in their time period, New Rightists call for the overcoming of the liberal, cosmopolitan Western Civilization to reassert the more profound cultural and spiritual identity of Europeans, based on the “regeneration of history” and a reference to their multi-form and multi-millennial heritage.

Lucian Tudor

Notes

[1] An example of such an assertion regarding cultural pessimism can be seen in “Part III. Three Major Expressions of Neo-Conservatism” in Klemens von Klemperer, Germany’s New Conservatism: Its History and Dilemma in the Twentieth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968).

[2] To supplement our short summary of Spenglerian philosophy, we would like to note that one the best overviews of Spengler’s philosophy in English is Stephen M. Borthwick, “Historian of the Future: An Introduction to Oswald Spengler’s Life and Works for the Curious Passer-by and the Interested Student,” Institute for Oswald Spengler Studies, 2011, <https://sites.google.com/site/spenglerinstitute/Biography>.

[3] Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West Vol. 1: Form and Actuality (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1926), p. 106.

[4] Ibid.

[5] See “Prussianism and Socialism” in Oswald Spengler, Selected Essays (Chicago: Gateway/Henry Regnery, 1967).

[6] For a good overview of Moeller’s thought, see Lucian Tudor, “Arthur Moeller van den Bruck: The Man & His Thought,” Counter-Currents Publishing, 17 August 2012, <http://www.counter-currents.com/2012/08/arthur-moeller-van-den-bruck-the-man-and-his-thought/>.

[7] See Fritz Stern, The Politics of Cultural Despair (Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1974), pp. 238-239, and Alain de Benoist, “Arthur Moeller van den Bruck,” Elementos: Revista de Metapolítica para una Civilización Europea No. 15 (11 June 2011), p. 30, 40-42. <http://issuu.com/sebastianjlorenz/docs/elementos_n__15>.

[8] Arthur Moeller van den Bruck as quoted in Benoist, “Arthur Moeller van den Bruck,” p. 41.

[9] Ibid., p. 41.

[10] Ibid., pp. 41-43.

[11] See Fritz K. Ringer, The Decline of the German Mandarins: The German Academic Community, 1890–1933 (Hanover: University Press of New England, 1990), pp. 183 ff.; John J. Haag, Othmar Spann and the Politics of “Totality”: Corporatism in Theory and Practice (Ph.D. Thesis, Rice University, 1969), pp. 24-26, 78, 111.; Alexander Jacob’s introduction and “Part I: The Intellectual Foundations of Politics” in Edgar Julius Jung, The Rule of the Inferiour, Vol. 1 (Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellon Press, 1995).

[12] For a brief introduction to Freyer’s philosophy, see Lucian Tudor, “Hans Freyer: The Quest for Collective Meaning,” Counter-Currents Publishing, 22 February 2013, <http://www.counter-currents.com/2013/02/hans-freyer-the-quest-for-collective-meaning/>.

[13] See Jerry Z. Muller, The Other God That Failed: Hans Freyer and the Deradicalization of German Conservatism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987), pp. 78-79, 120-121.

[14] Ibid., p. 335.

[15] Ibid., p. 79.

[16] See Julius Evola, The Path of Cinnabar (London: Integral Tradition Publishing, 2009), pp. 203-204.

[17] See H.T. Hansen, “Julius Evola’s Political Endeavors,” in Julius Evola, Men Among the Ruins: Postwar Reflections of a Radical Traditionalist (Rochester: Inner Traditions, 2002), pp. 15-17.

[18] Evola, Path of Cinnabar, p. 204.

[19] Robert Steuckers, “Evola & Spengler”, Counter-Currents Publishing, 20 September 2010, <http://www.counter-currents.com/2010/09/evola-spengler/> .

[20] Ibid.

[21] In a description that applies as much to the New Right as to the Eurasianists, Alexander Dugin wrote of a vision in which “the formal opposition between tradition and modernity is removed… the realities superseded by the period of Enlightenment obtain a legitimate place – these are religion, ethnos, empire, cult, legend, etc. In the same time, a technological breakthrough, economical development, social fairness, labour liberation, etc. are taken from the Modern” (See Alexander Dugin, “Multipolarism as an Open Project,” Journal of Eurasian Affairs Vol. 1, No. 1 (September 2013), pp. 12-13).

[22] Alain de Benoist, “Oswald Spengler,” Elementos: Revista de Metapolítica para una Civilización Europea No. 10 (15 April 2011), p. 13.<http://issuu.com/sebastianjlorenz/docs/elementos_n__10>.

[23] Pierre Krebs, Fighting for the Essence (London: Arktos, 2012), p. 34.

[24] Sebastian J. Lorenz, “El Decadentismo Occidental, desde la Konservative Revolution a la Nouvelle Droite,”Elementos No. 10, p. 5.

Der Sohn eines sächsischen Postdirektors erhielt seine Gymnasialausbildung am königlichen Elitegymnasium zu Dresden-Neustadt, studierte von 1907 bis 1911 in Leipzig Philosophie, Psychologie, Nationalökonomie und Geschichte, u.a. bei Wilhelm Wundt und Karl Lamprecht, in deren universalhistorischer Tradition er seine ersten Arbeiten zur Geschichtsauffassung der Aufklärung (Diss. 1911) und zur Bewertung der Wirtschaft in der deutschen Philosophie des 19. Jahrhunderts (Habilitation 1921) verfaßte. Nach zusätzlichen Studien in Berlin mit engen Kontakten zu Georg Simmel und Lehrtätigkeit an der Reformschule der Freien Schulgemeinde Wickersdorf kämpfte F. mit dem Militär-St.-Heinrichs-Orden ausgezeichnet im Ersten Weltkrieg. Als Mitglied des von Eugen Diederichs initiierten Serakreises der Jugendbewegungverfaßte F. an die Aufbruchsgeneration gerichtete philosophischen Schriften: Antäus (1918), Prometheus (1923), Pallas Athene (1935). Von 1922 bis 1925 lehrte er als Ordinarius hauptsächlich Kulturphilosophie an der Universität Kiel, erhielt 1925 den ersten deutschen Lehrstuhl für Soziologie ohne Beiordnung eines anderen Faches in Leipzig und widmete sich von nun an der logischen und historisch-philosophischen Grundlegung dieser neuen Disziplin. In Auseinandersetzung mit dem Positivismus seiner Lehrer und mit der Philosophie Hegels sollten typische gesellschaftliche Grundstrukturen herausgearbeitet und ihre historischen Entwicklungsgesetze gefunden werden. Darüber hinaus ist für F. die Soziologie als konkrete historische Erscheinung, erst durch die abendländische Aufklärung möglich geworden, Äußerung einer vorher nie dagewesenen gesellschaftlichen Emanzipation zur wissenschaftlichen Selbstreflexion, drückt deshalb als "Wirklichkeitswissenschaft" in der Erfassung des gegenwärtigen gesellschaftlichen Wandels auch den kollektiven Willen aus, ist also als Wissenschaft zugleich politische Ethik, die die Richtung des gesellschaftlichen Wandels zu bestimmen hat.

Der Sohn eines sächsischen Postdirektors erhielt seine Gymnasialausbildung am königlichen Elitegymnasium zu Dresden-Neustadt, studierte von 1907 bis 1911 in Leipzig Philosophie, Psychologie, Nationalökonomie und Geschichte, u.a. bei Wilhelm Wundt und Karl Lamprecht, in deren universalhistorischer Tradition er seine ersten Arbeiten zur Geschichtsauffassung der Aufklärung (Diss. 1911) und zur Bewertung der Wirtschaft in der deutschen Philosophie des 19. Jahrhunderts (Habilitation 1921) verfaßte. Nach zusätzlichen Studien in Berlin mit engen Kontakten zu Georg Simmel und Lehrtätigkeit an der Reformschule der Freien Schulgemeinde Wickersdorf kämpfte F. mit dem Militär-St.-Heinrichs-Orden ausgezeichnet im Ersten Weltkrieg. Als Mitglied des von Eugen Diederichs initiierten Serakreises der Jugendbewegungverfaßte F. an die Aufbruchsgeneration gerichtete philosophischen Schriften: Antäus (1918), Prometheus (1923), Pallas Athene (1935). Von 1922 bis 1925 lehrte er als Ordinarius hauptsächlich Kulturphilosophie an der Universität Kiel, erhielt 1925 den ersten deutschen Lehrstuhl für Soziologie ohne Beiordnung eines anderen Faches in Leipzig und widmete sich von nun an der logischen und historisch-philosophischen Grundlegung dieser neuen Disziplin. In Auseinandersetzung mit dem Positivismus seiner Lehrer und mit der Philosophie Hegels sollten typische gesellschaftliche Grundstrukturen herausgearbeitet und ihre historischen Entwicklungsgesetze gefunden werden. Darüber hinaus ist für F. die Soziologie als konkrete historische Erscheinung, erst durch die abendländische Aufklärung möglich geworden, Äußerung einer vorher nie dagewesenen gesellschaftlichen Emanzipation zur wissenschaftlichen Selbstreflexion, drückt deshalb als "Wirklichkeitswissenschaft" in der Erfassung des gegenwärtigen gesellschaftlichen Wandels auch den kollektiven Willen aus, ist also als Wissenschaft zugleich politische Ethik, die die Richtung des gesellschaftlichen Wandels zu bestimmen hat. F. war ab 1933 Direktor des Instituts für Kultur- und Universalgeschichte an der Leipziger Universität. Als neu gewählter Präsident der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Soziologie legte er diese 1933 still, um eine politische "Gleichschaltung" zu verhindern. Den damaligen europäischen politischen Umbrüchen brachte F. als Theoretiker des Wandels zunächst offenes Interesse entgegen, fühlte sich der theoretischen Erfassung dieser Entwicklungen verpflichtet und war deshalb nie aktives Mitglied einer politischen Partei oder Bewegung; er wurde später der "konservativen Revolution" der zwanziger Jahre als "jungkonservativer Einzelgänger" (Mohler) zugeordnet. Die vor 1933 noch idealistisch formulierte Konzeption des Staates als höchste Form der Kultur (1925) hat F. im Lauf der bedrohlichen politischen Entwicklung revidiert in seinen Studien über Machiavelli (1936) und Friedrich den Großen (Preußentum und Aufklärung 1944) durch einen realistischen Staatsbegriff, der ausschließlich durch Gemeinwohl, langfristige gesellschaftliche Entwicklungsperspektiven und durch prozessuale Kriterien der Legitimität gerechtfertigt ist: durch den Dienst am Staat, der aber den Menschen keinesfalls total vereinnahmen darf, sowie die Prägekraft des Staates, der dem Kollektiv ein gemeinsames Ziel gibt, aber dennoch die Freiheit und Menschenwürde seiner Bürger bewahrt. Insbesondere gelang F. in der Darstellung der Legitimität als generellem Gesetz jeder Politik eine dialektische Verknüpfung des naturrechtlichen Herrschaftsgedankens mit der klassischen bürgerlich-humanitären Aufklärung: Nur die Herrschaft ist legitim, die dem Sinn ihres Ursprungs entspricht - es muß das erfüllt werden, was das Volk mit der Einsetzung der Herrschaft gewollt hat.

F. war ab 1933 Direktor des Instituts für Kultur- und Universalgeschichte an der Leipziger Universität. Als neu gewählter Präsident der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Soziologie legte er diese 1933 still, um eine politische "Gleichschaltung" zu verhindern. Den damaligen europäischen politischen Umbrüchen brachte F. als Theoretiker des Wandels zunächst offenes Interesse entgegen, fühlte sich der theoretischen Erfassung dieser Entwicklungen verpflichtet und war deshalb nie aktives Mitglied einer politischen Partei oder Bewegung; er wurde später der "konservativen Revolution" der zwanziger Jahre als "jungkonservativer Einzelgänger" (Mohler) zugeordnet. Die vor 1933 noch idealistisch formulierte Konzeption des Staates als höchste Form der Kultur (1925) hat F. im Lauf der bedrohlichen politischen Entwicklung revidiert in seinen Studien über Machiavelli (1936) und Friedrich den Großen (Preußentum und Aufklärung 1944) durch einen realistischen Staatsbegriff, der ausschließlich durch Gemeinwohl, langfristige gesellschaftliche Entwicklungsperspektiven und durch prozessuale Kriterien der Legitimität gerechtfertigt ist: durch den Dienst am Staat, der aber den Menschen keinesfalls total vereinnahmen darf, sowie die Prägekraft des Staates, der dem Kollektiv ein gemeinsames Ziel gibt, aber dennoch die Freiheit und Menschenwürde seiner Bürger bewahrt. Insbesondere gelang F. in der Darstellung der Legitimität als generellem Gesetz jeder Politik eine dialektische Verknüpfung des naturrechtlichen Herrschaftsgedankens mit der klassischen bürgerlich-humanitären Aufklärung: Nur die Herrschaft ist legitim, die dem Sinn ihres Ursprungs entspricht - es muß das erfüllt werden, was das Volk mit der Einsetzung der Herrschaft gewollt hat. Zentraler Gesichtspunkt seiner Nachkriegsschriften war die gegenwärtige Epochenschwelle, der Übergang der modernen Industriegesellschaft zur weltweit ausgreifenden wissenschaftlich-technischen Rationalität, deren "sekundäre Systeme" alle naturhaft gewachsenen Lebensformen erfassen. F. weist nach, wie diese Fortschrittsordnung zum tragenden Kulturfaktor wird in allen Teilentwicklungen: der Technik, Siedlungsformen, Arbeit und Wertungen. Seine frühere integrative Perspektive einer Kultursynthese wird ersetzt durch den Konflikt von eigengesetzlichen, künstlichen Sachwelten einerseits und den "haltenden Mächte" des sozialen Lebens andererseits, die im "Katarakt des Fortschritts" auf wenige, die private Lebenswelt beherrschende Gemeinschaftsformen beschränkt sind. Jedoch bleibt die Synthese von "Leben" und "Form", von Menschlichkeit und technischer Zivilisation für F. weiterhin unerläßlich für den Fortbestand jeder Kultur, im krisenhaften Übergang noch nicht erreicht, aber durchaus denkbar jenseits der Schwelle, wenn sich die neue geschichtliche Epoche der weltumspannenden Industriekultur konsolidieren wird. F.s Theorie der Industriekultur, kurz vor seinem Tode begonnen, ist unvollendet geblieben. Sein strukturhistorisches Konzept der Epochenschwelle hat in der deutschen Nachkriegssoziologie weniger Aufnahme gefunden, während es in der deutschen Geschichtswissenschaft wesentlich zur Überwindung einer evolutionären Entwicklungsgeschichte beigetragen hat und eine sozialwissenschaftlich orientierte Strukturgeschichtsschreibung einleitete, wofür F.s Konzept der Eigendynamik der sekundären Systeme ebenso ausschlaggebend war.

Zentraler Gesichtspunkt seiner Nachkriegsschriften war die gegenwärtige Epochenschwelle, der Übergang der modernen Industriegesellschaft zur weltweit ausgreifenden wissenschaftlich-technischen Rationalität, deren "sekundäre Systeme" alle naturhaft gewachsenen Lebensformen erfassen. F. weist nach, wie diese Fortschrittsordnung zum tragenden Kulturfaktor wird in allen Teilentwicklungen: der Technik, Siedlungsformen, Arbeit und Wertungen. Seine frühere integrative Perspektive einer Kultursynthese wird ersetzt durch den Konflikt von eigengesetzlichen, künstlichen Sachwelten einerseits und den "haltenden Mächte" des sozialen Lebens andererseits, die im "Katarakt des Fortschritts" auf wenige, die private Lebenswelt beherrschende Gemeinschaftsformen beschränkt sind. Jedoch bleibt die Synthese von "Leben" und "Form", von Menschlichkeit und technischer Zivilisation für F. weiterhin unerläßlich für den Fortbestand jeder Kultur, im krisenhaften Übergang noch nicht erreicht, aber durchaus denkbar jenseits der Schwelle, wenn sich die neue geschichtliche Epoche der weltumspannenden Industriekultur konsolidieren wird. F.s Theorie der Industriekultur, kurz vor seinem Tode begonnen, ist unvollendet geblieben. Sein strukturhistorisches Konzept der Epochenschwelle hat in der deutschen Nachkriegssoziologie weniger Aufnahme gefunden, während es in der deutschen Geschichtswissenschaft wesentlich zur Überwindung einer evolutionären Entwicklungsgeschichte beigetragen hat und eine sozialwissenschaftlich orientierte Strukturgeschichtsschreibung einleitete, wofür F.s Konzept der Eigendynamik der sekundären Systeme ebenso ausschlaggebend war.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg