dimanche, 26 janvier 2025

Identité politico-civilisationnelle et période axiale chez l'égyptologue et philosophe allemand Jan Assmann

Identité politico-civilisationnelle et période axiale chez l'égyptologue et philosophe allemand Jan Assmann

NdlR: Soucieux d'approfondir les thèses énoncées par Jan Assmann, nous présentons ici un résumé succinct des deux thèmes majeurs de sa pensée, en attendant de nous immerger plus complètement dans les méandres de celle-ci. Aborder la notion de "période axiale" implique de se rappeler des thèses de Karl Jaspers et de Karen Armstrong. Les réponses ci-dessous sont "neutres" et ne révèlent pas notre approche critique de cette notion qui interpelle directement notre vision de l'histoire, Armin Mohler et Giorgio Locchi nous ayant légué également une interprétation rupturaliste de la notion de "période axiale".

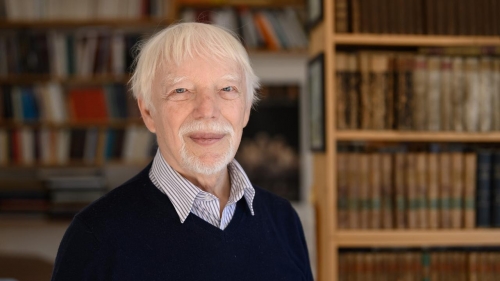

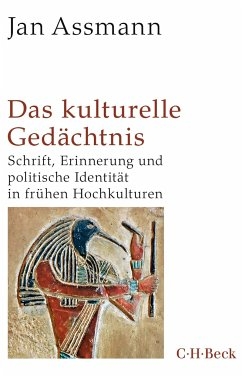

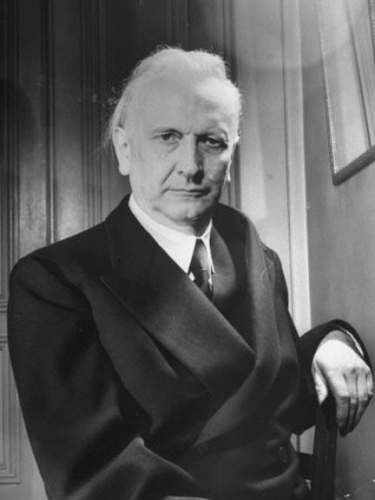

Le philosophe allemand contemporain Jan Assmann a écrit des pages d'une grande profondeur sur "l'écriture, la mémoire et l'identité politique dans les hautes cultures de l'antiquité". De même, il a consacré un ouvrage à la "période axiale" de l'histoire, thème qu'avait inauguré le philosophe protestant Karl Jaspers. Pouvez-vous nous dire en quoi consiste sa vision de l'identité politique des hautes civilisations de jadis et en quoi consiste son approche des "périodes axiales de l'histoire, et, accessoirement, quelle est la différence entre son approche et celle de Karl Jaspers?

1) La vision de Jan Assmann sur l'identité politique des hautes civilisations

Jan Assmann, égyptologue et spécialiste de la mémoire culturelle, explore comment les civilisations antiques ont construit leur identité politique autour de pratiques mémorielles, d'institutions religieuses et de formes spécifiques d'écriture. Sa réflexion repose sur plusieurs idées centrales :

L’écriture et la mémoire culturelle

Assmann distingue la mémoire culturelle de la mémoire communicative.

La mémoire culturelle est le socle d’une identité collective, transmise sur plusieurs générations, souvent à travers des supports écrits, des mythes, des rituels et des monuments.

Les civilisations antiques, comme l'Égypte, ont utilisé l’écriture pour archiver leurs lois, rituels religieux et récits fondateurs, qui servaient à structurer et légitimer leur identité politique et culturelle.

L’écriture permet ainsi de figer le temps et de relier les générations présentes aux mythes fondateurs, en construisant une continuité historique et une légitimité politique.

Identité politique et théologie

Assmann souligne que, dans les hautes cultures, l'identité politique est souvent enracinée dans une conception théologique du pouvoir. Par exemple, en Égypte ancienne, le pharaon n’est pas simplement un dirigeant politique, mais l’intermédiaire entre les dieux et les hommes. Cette fusion du pouvoir divin et politique est un trait clé des premières civilisations complexes.

Il introduit également le concept de "distinction mosaïque", en opposition au polythéisme, pour analyser l’émergence du monothéisme (notamment dans le judaïsme) et son rôle dans la formation d’identités politiques exclusives, fondées sur des frontières entre le "vrai" et le "faux" dieu.

Le rôle des récits fondateurs

Les mythes, lois et rituels ne sont pas de simples traditions, mais des outils politiques puissants pour consolider le pouvoir, maintenir l’ordre social et justifier les institutions.

2) La "période axiale" chez Jan Assmann et Karl Jaspers

Le concept de "période axiale" selon Karl Jaspers

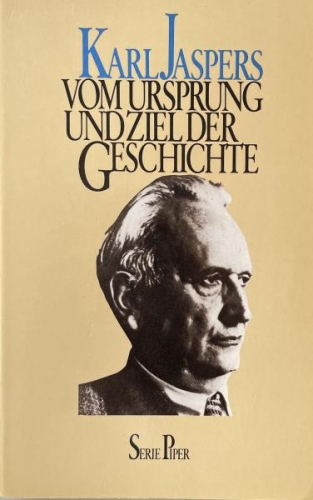

Karl Jaspers, philosophe protestant, a introduit le concept de période axiale dans son ouvrage Vom Ursprung und Ziel der Geschichte (1949). Il identifie une période historique charnière, située entre 800 et 200 avant notre ère, où plusieurs civilisations à travers le monde ont simultanément connu des révolutions spirituelles et intellectuelles majeures.

Cette période voit l'émergence de grandes figures fondatrices comme Confucius, Bouddha, Socrate, les prophètes hébraïques, et des textes fondamentaux tels que les Upanishads ou les dialogues platoniciens.

Pour Jaspers, cette période marque un tournant où l’humanité prend conscience de la transcendance, de l’individu et de l’éthique universelle.

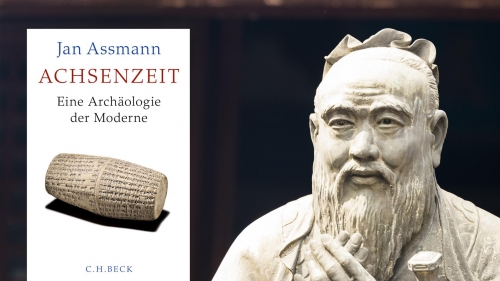

La relecture de la période axiale par Jan Assmann

Jan Assmann reprend le concept, mais il y apporte une approche anthropologique et culturelle :

Il insiste sur le rôle des pratiques mémorielles et des textes écrits dans la transmission des idées de la période axiale. Selon lui, cette période est également marquée par une transition vers des formes d'identités collectives basées sur des textes fondateurs et des traditions mémorisées (ex. la Torah dans le judaïsme ou les Védas dans l’hindouisme).

Contrairement à Jaspers, qui met l’accent sur une évolution presque spirituelle et universelle de l’humanité, Assmann analyse les spécificités culturelles et historiques de chaque civilisation. Il soutient que les changements de la période axiale ne sont pas universels, mais fortement dépendants des contextes sociaux, politiques et religieux locaux.

Différences entre Jaspers et Assmann

Approche universaliste vs particulariste :

Jaspers interprète la période axiale comme une évolution collective et presque simultanée de l’esprit humain vers des valeurs transcendantales.

Assmann, au contraire, insiste sur le rôle des systèmes de transmission culturelle et les diversités de chaque culture.

Centralité des textes et de la mémoire :

Jaspers met en avant les idées philosophiques et spirituelles universelles, tandis qu’Assmann insiste sur le rôle des textes écrits et des institutions mémorielles dans la formation des identités politiques et religieuses.

Émergence du monothéisme :

Assmann explore davantage les implications de la période axiale pour l'émergence du monothéisme, qu’il considère comme une révolution culturelle ayant des conséquences profondes sur les identités collectives.

3) En résumé

Jan Assmann apporte une profondeur anthropologique au concept de Jaspers, en examinant comment les textes, les pratiques mémorielles et les institutions ont contribué à structurer les identités politiques et religieuses des hautes civilisations. Là où Jaspers voit une évolution universelle de l'esprit humain, Assmann met en lumière la diversité des réponses culturelles et historiques, tout en montrant comment elles ont influencé la mémoire collective et l’organisation sociale.

Et quel est le rapport entre ces deux philosophes allemands, qui ont planché sur la notion de "période axiale" et les travaux de Karen Armstrong dans l'anglosphère qui, elle aussi, réanime cette thématique philosophique qui avait été quelque peu oubliée?

Karen Armstrong, dans l’anglosphère, reprend et développe le concept de "période axiale" introduit par Karl Jaspers, en y apportant une perspective qui dialogue indirectement avec les travaux de Jan Assmann et enrichit l'approche en l'adaptant à des préoccupations contemporaines. Voici les liens et divergences entre ces trois penseurs :

1) Karl Jaspers et la conceptualisation initiale

Jaspers introduit l’idée d’une période axiale comme une époque historique entre 800 et 200 avant notre ère où les grandes civilisations du monde (Inde, Chine, Proche-Orient, Grèce) ont connu des transformations spirituelles et intellectuelles fondamentales.

Pour lui, cette époque marque la naissance des grands cadres de pensée universelle, comme la quête de transcendance, la réflexion éthique, et l’idée de l’individu en tant qu’agent moral.

Cette vision universaliste a marqué la réflexion philosophique et reste un socle théorique pour les travaux ultérieurs.

2) Jan Assmann et l’approche anthropologique

Assmann reprend l’idée de Jaspers, mais en s'intéressant aux mécanismes culturels qui ont permis la transmission des idées axiales.

Il met un accent particulier sur la mémoire culturelle et les textes fondateurs comme outils de transmission et de structuration des sociétés. Il explore notamment le rôle du monothéisme, qui émerge dans cette période, et ses implications sur l’identité collective et politique.

Là où Jaspers voyait une évolution presque simultanée et universelle de l’humanité, Assmann insiste sur les variations culturelles et les contextes historiques spécifiques des transformations de cette période.

3) Karen Armstrong et la réhabilitation de la période axiale

Dans son ouvrage The Great Transformation (2006), Karen Armstrong revisite le concept de période axiale avec un objectif clair: démontrer la pertinence contemporaine de cette époque fondatrice pour répondre aux crises éthiques, spirituelles et politiques actuelles.

Elle met en avant une lecture plus théologique et humaniste des figures et courants de cette période (Bouddha, Confucius, Socrate, les prophètes hébreux, etc.), en insistant sur leur quête commune: résoudre la souffrance humaine et instaurer une éthique universelle basée sur la compassion et la justice.

Elle partage avec Jaspers l’idée que ces transformations ont eu lieu simultanément dans des régions éloignées, mais elle souligne également leur intemporalité, en montrant comment elles peuvent inspirer le monde contemporain.

4) Points de convergence entre Armstrong, Jaspers et Assmann

Une humanité en quête de transcendance et d'éthique :

Tous trois voient la période axiale comme une étape cruciale où l’humanité a développé des outils pour penser la condition humaine, la souffrance et le sens de l’existence.

Importance des figures fondatrices :

Jaspers met l’accent sur les grands penseurs, Assmann sur leurs textes et contextes, tandis qu’Armstrong explore leur message moral et spirituel.

Relecture de cette période pour le présent :

Armstrong, comme Assmann, fait un lien explicite entre les enseignements de cette époque et les défis contemporains, qu’il s’agisse de violence religieuse, de crise de sens ou de conflits identitaires.

5) Différences entre Armstrong et les philosophes allemands

Avec Jaspers :

Armstrong dépasse la vision purement philosophique ou métaphysique de Jaspers en mettant l’accent sur les dynamiques sociales et pratiques des religions de la période axiale. Elle insiste notamment sur leur rôle dans la création d’une éthique universelle fondée sur la compassion, une dimension que Jaspers aborde moins directement.

Avec Assmann :

Là où Assmann explore la période axiale à travers le prisme de la mémoire culturelle et des textes, Armstrong adopte une approche plus narrative et accessible, centrée sur les enseignements moraux des grandes figures axiales.

Armstrong insiste davantage sur les éléments de continuité spirituelle entre cette période et les enjeux actuels. Assmann, pour sa part, est plus attentif aux ruptures qu’elle introduit, notamment avec la "distinction mosaïque" et les tensions qu’elle crée dans les conceptions religieuses.

6) Une synthèse des trois approches

Karen Armstrong peut être vue comme un pont entre les travaux de Jaspers et Assmann :

Elle partage avec Jaspers une fascination pour les révolutions spirituelles universelles et leurs implications philosophiques.

Elle s’aligne avec Assmann dans son intérêt pour les contextes historiques et culturels spécifiques, mais sans adopter son analyse érudite des textes ou son insistance sur les institutions mémorielles.

Sa vision, plus pratique et centrée sur l’éthique contemporaine, cherche à rendre la période axiale pertinente pour un large public, en tant qu’inspiration pour résoudre les crises modernes.

Conclusion

Les trois auteurs enrichissent le concept de période axiale de manières complémentaires : Jaspers offre une vision philosophique et universaliste, Assmann une lecture anthropologique et contextuelle, tandis qu’Armstrong donne une interprétation théologique et humaniste, axée sur les enjeux contemporains. Ensemble, leurs approches forment une constellation d’idées qui approfondissent notre compréhension de cette période fondamentale de l’histoire humaine.

21:13 Publié dans Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, jan assmann, karl jaspers, karen armstrong, période axiale de l'histoire |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 29 novembre 2014

Karl Jaspers, the Axial Age, and a Common History for Humanity

Karl Jaspers, the Axial Age, and a Common History for Humanity

|

| The Philosophers of the "Axial Age": Socrates, Confucius, Buddha and Zarathustra |

But this Western-oriented teaching was increasingly rejected by historians who felt that all the peoples of the earth deserved equal attention. A major difficulty confronted this feeling: how can a new history of all humans — "universal" in this respect — be constructed in light of the clear pre-eminence of Europeans in so many fields?

It soon became apparent that the key was to do away with the idea of progress, which had become almost synonymous with the achievements of the West. The political climate was just right, the West was at the center of everything that seemed wrong in the world and in opposition to everything that aspired to be good: the threat of nuclear destruction, the prolonged Vietnam War, the rise of pan-Arabic and pan African identities, the "liberation movements" in Latin America, the Black civil rights riots, the women's movement.

More than anything, the affluent West was at the center of a world capitalist system wherein the rest of the world seemed to be systematically "underdeveloped" at the expense of the very "progression" of the West. Millions of students were being taught that the capitalist West, in the words of Karl Marx, had progressed to become master of the world "dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt".

The idea of Western progress was eventually replaced with the idea of "world history connected". Students would now have to learn that all humans irrespective of cultural and historical differences were alike as homo sapiens, as members of the same planet, and as migratory creatures who had made history in unison. The aim was hardly that Europeans were creatively involved in the creation of Chinese, Mesopotamian, or Mayan civilization; it was that they were morally and economically responsible for the "underdevelopment" of civilizations that were once more developed than the Germanic Barbarians of the Dark Ages — while insisting simultaneously that non-Europeans were the ultimate originators or co-participators of every great epoch in Europe's history.

But before this great fabrication was imposed on unsuspecting white students, a preparatory, though by no means identical, idea had been articulated by a German named Karl Jaspers: the notion that the major civilizations of the Old World experienced, more or less at the same time, a "spiritual process" characterized by a common set of religious, psychological, and philosophical inquiries about what it means to be "specifically human". The argument was that humanity, at this point in history, together, came to pose universal questions about the meaning of life with similar answers.

The Goal of Jasper's Axial Age

Jaspers, a highly respected philosopher, argued in The Origin and Goal of History which was published in 1949 a few years after the end of WWII that Western culture was not uniquely gifted with ideas that bespoke of mankind generally and the course of history universally; other major civilizations, too, had espoused outlooks about humanity together with moral precepts with universal content.

Jaspers, a highly respected philosopher, argued in The Origin and Goal of History which was published in 1949 a few years after the end of WWII that Western culture was not uniquely gifted with ideas that bespoke of mankind generally and the course of history universally; other major civilizations, too, had espoused outlooks about humanity together with moral precepts with universal content. Jaspers believed that this ability was "empirically" made possible by the occurrence of a fundamental "spiritual" change between 800 and 200 BC, which gave "rise to a common frame of historical self-comprehension for all peoples — for the West, for Asia, and for all men on earth, without regard to particular articles of faith". Believing that these spiritual changes occurred simultaneously across the world, Jaspers called it the "Axial Period". It is worth quoting in full Jasper's identification of the main protagonists of this period:

The most extraordinary events are concentrated in this period. Confucius and Lao-tse were living in China, all the schools of Chinese philosophy came into being, including those of Mo-ti, Chuang-tse, Lieh-tsu and a host of others; India produced the Upanishads and Buddha and, like China, ran the whole gamut of philosophical possibilities down to skepticism, to materialism , sophism and nihilism; in Iran Zarathustra taught a challenging view of the world as a struggle between good and evil; in Palestine the prophets made their appearance, from Elijah, by way of Isaiah and Jeremiah to Deutero-Isaiah; Greece witnessed the appearance of Homer, of the Philosophers — Parmenides, Heraclitus and Plato — of the tragedians, Thucydides and Archimedes. Everything implied by these names developed during these few centuries almost simultaneously in China, India, and the West, without any one of these regions knowing of the others (2).

The Greek, Indian and Chinese philosophers were unmythical in their decisive insights, as were the prophets [of the Bible] in their ideas of God (3).

It is not that the philosophical outlooks of these civilizations were identical, but that they exhibited similar breakthroughs in posing universal questions about the "human condition", what is the ultimate source of all things? what is our relation to the universe? what is the Good? what are human beings? Prior cultures were more particularized, tribal, polytheistic, and devoid of self-awareness regarding the universal characteristics of human existence. From the Axial Age onward, "world history receives the only structure and unity that has endured — at least until our own time" (8).

The central aim of Jasper's book was to drive home the notion that the different faiths and races of the world were once running along "parallel lines" of spiritual development, and that we should draw on this "common" spiritual source to avoid the calamity of another World War. The fact that these civilizations had reached a common spiritual point of development, without any direct influences between them, was likely, in his view, the "manifestation of some profound common element, the one primal source of humanity" (12). We humans have much in common despite our differences.

German Guilt requires a Common History

This notion of an Axial Age, with which Jaspers came to be identified, and which has been accepted by many established world historians, historical sociologists and philosophers, is also a claim he felt in a personal way (as a German) in the aftermath of the Second World War. According to Jaspers, after the end of the Axial Age around 200 BC, the major civilizations had ceased to follow "parallel movements close to each other" and instead began to "diverge" and "finally became deeply estranged from one another" (12). The Nazi experience was, in his estimation, an extreme case of divergence.

This notion of an Axial Age, with which Jaspers came to be identified, and which has been accepted by many established world historians, historical sociologists and philosophers, is also a claim he felt in a personal way (as a German) in the aftermath of the Second World War. According to Jaspers, after the end of the Axial Age around 200 BC, the major civilizations had ceased to follow "parallel movements close to each other" and instead began to "diverge" and "finally became deeply estranged from one another" (12). The Nazi experience was, in his estimation, an extreme case of divergence. It should be noted, in this vein, that Jaspers, whose wife was Jewish, was the author of a much discussed book, The Question of German Guilt, in which he extended culpability to Germany as a whole, to every German even those who were not members of the Nazi party. A passage from this book, cited upfront in a BBC documentary, The Nazis — A Warning from History, reads:

That which has happened is a warning. To forget it is guilt. It must be continually remembered. It was possible for this to happen, and it remains possible for it to happen again at any minute. Only in knowledge can it be prevented.

Hannah Arendt

An interesting figure drawn to the idea of a common historical experience, in the early days after WWII, was Hannah Arendt, a student of Jaspers. She obtained a copy of The Origin and Goal of History as she was completing her widely acclaimed book, The Origins of Totalitarianism. It is quite revealing that Elisabeth Young-Bruehl's traces, in a short essay titled Hannah Arendt's Jewish Identity, the roots of Arendt's cosmopolitanism to the role of the Jews of Palestine as one of the Axial Age peoples. Together with Jaspers, Arendt came to share

the project of thinking about what kind of history was needed for facing the events of the war and the Holocaust and for considering how the world might be after the war. They agreed that the needed history should not be national or for a national purpose, but for humankind.

It is Arendt's Jewish identity — not just the identity she asserted in defending herself as a Jew when attacked as one, but more deeply her connection to the Axial Age prophetic tradition — that made her the cosmopolitan she was.

- "enlarge" their minds and include the experience and views of other cultures in their thinking;

- to overcome their Eurocentric prejudices and encompass the entire world in their historical reflections;

- to develop a sense of the "human condition" and learn how to talk about what is "common to all mankind";

- to learn how they are culturally shaped both by their particular conditions and the conditions and experiences shared by all humans on the planet.

The "Special Quality" of the West — Rejected

This call by Arendt would coalesce with similar arguments about the "inventions of nations", the "social construction of races", and the idea that we are all primordially alike as Homo Sapiens. Jaspers, at least in his book The Origin and Goal of History, did not go this far, but in fact retracted, in later chapters, from the general statements he made in the introduction about the Axial Age being a common spiritual experience across the planet, acknowledging the obvious:

it was not a universal occurrence...There were the great peoples of the ancient civilizations, who lived before and even concurrently with the [Axial] breakthrough, but had no part in it (51).

in Asia, on the other hand, a constant situation persists; it modifies its manifestations, it founders in catastrophes and re-establishes itself on the one and only basis as that which is constantly the same (53).

if science and technology were created in the West, we are faced with the question: Why did this happen in the West and not in the other two great cultural zones (61-2)?

Here are more special qualities mentioned by Jaspers about the West: "Tragedy is known only to the West." While other Axial cultures spoke of mankind in general, in the West this universal ambition regarding the place of man in the cosmos and the good life did not "coagulate into a dogmatic fixity" (64). "The West gives the exception room to move." In the West "human nature reaches a height that is certainly not shared by all and to which...hardly anyone ascends." "...the perpetual disquiet of the West, its continual dissatisfaction, its inability to be content with any sort of fulfillment" (64).

This is the language of Spengler's Faustian Soul. Some in the New Right don't like this perpetual restlessness about the West and would prefer to see the West become one more boring traditional culture. But this cannot be, for "in contrast to the uniformity and relative freedom from tension of all Oriental empires":

the West is typified by resoluteness that takes things to extremes, elucidates them down to the last detail, places them before the either-or, and so brings awareness of the underlying principles and sets up battle-fronts in the inmost recesses of the mind. (65)

Yet, there never was an Axial Age: the PreSocratics were dramatically different in their inquiries, and far more universal in their reasoning, than the prophets of the Old Testament, the major schools of Confucianism, Taoism, and Legalism in China, and the Hindu religions of India. As far as I know, no one has explained this seemingly paradoxical combination of extreme Western uniqueness and extreme universalism. I hope to address this topic in a future essay.

00:05 Publié dans Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, allemagne, karl jaspers |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook