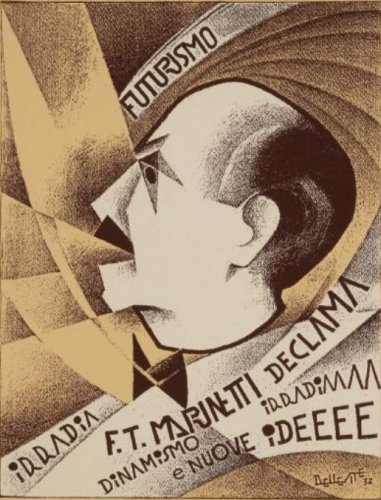

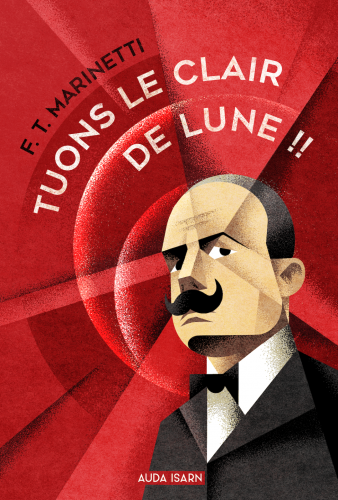

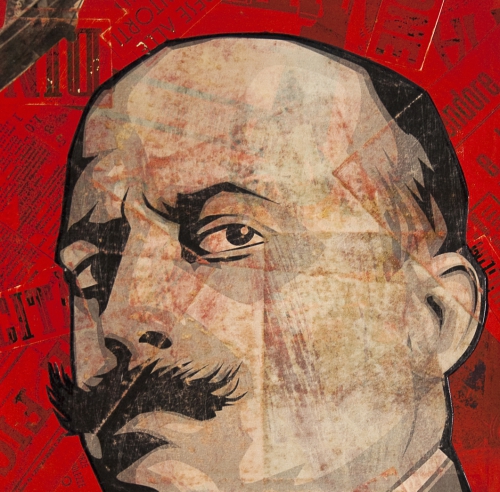

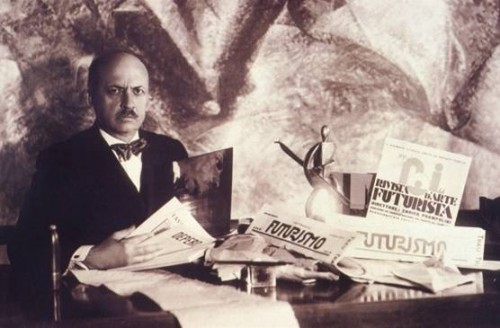

« Une automobile rugissante, qui a l'air de courir sur de la mitraille, est plus belle que la Victoire de Samothrace». Filipo Tommaso Marinetti l'affirme dans un manifeste, publié, le 20 février 1909, dans « Le Figaro».

Pour lancer cette proclamation, qui condamne « l'immobilité pensive» et exalte « le mouvement agressif..., le pas gymnastique, le saut périlleux, la gifle et le coup de poing», le poète italien a choisi Paris. Son pays, estime-t-il, ne convient pas à une telle entreprise.

Choix paradoxal, puisque l'auteur entend bien demeurer essentiellement italien, et donner au « futurisme», dont il expose les principes, un caractère national. Paris est alors la ville accueillante à toutes les créations littéraires et artistiques. Naturalisme, impressionnisme, symbolisme, orphisme, nabisme, fauvisme, cubisme y ont suscité des curiosités inlassables et des débats passionnés.

L'Italie, au contraire, demeure soumise aux disciplines classiques. Dans le Nord, son développement industriel paraît requérir toutes ses énergies.

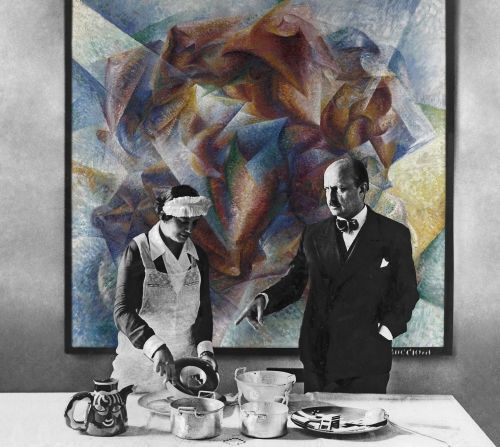

Marinetti n'est qu'un homme de lettres, mais un an (presque jour pour jour) après son manifeste, cinq peintres italiens qui ont adopté ses principes en publient un à leur tour, Ils se nomment Boccioni, Carra, Russolo, Baila, Severini.

En Italie, cette déclaration de principes fait, selon l'un de ses signataires, « l'effet d'une décharge électrique».

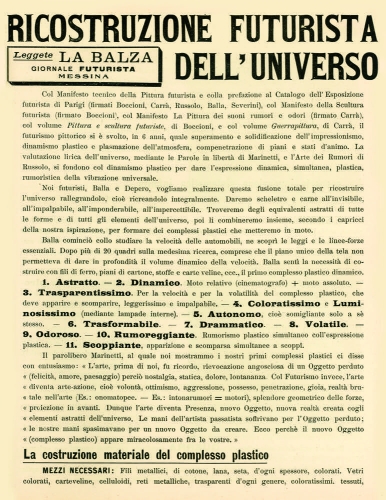

Au mois d'avril suivant, les «cinq» publient un nouveau document : le « Manifeste technique de la peinture futuriste».

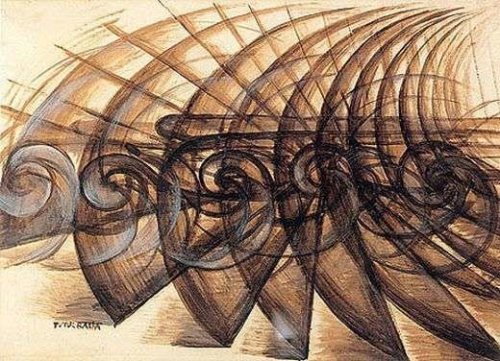

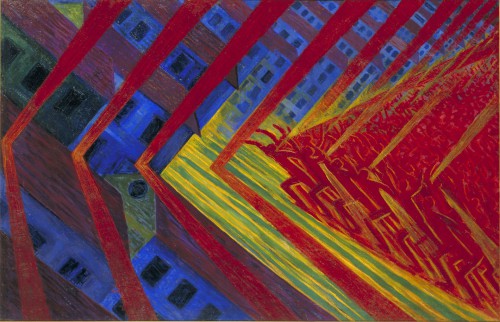

La prééminence du dynamique sur le statique y est affirmée. La nouvelle peinture traduira dans son langage « la vie moderne fragmentaire et rapide».

« II faut mépriser toutes les formes d'imitation». Le mouvement et la lumière doivent anéantir la matérialité des corps. Le nu, encore triomphant dans les salons, est déclaré aussi nauséeux en peinture que l'adultère en littérature. Les futuristes exigent sa suppression totale pour dix ans.

L'absolutisme même des allégations futuristes ne facilite pas, en 1910, l'approbation des théories nouvelles par l'opinion italienne. Aussi est-ce à Paris que, grâce à Gino Severini, qui est venu y résider, la première grande exposition futuriste peut avoir lieu. Elle se tient en février 1912 à la galerie Bernheim-Jeune.

Soixante et un ans après cette manifestation historique, c'est encore Paris qui présente, au Musée d'art moderne, une rétrospective de ce mouvement.

Près de quatre-vingt-dix peintures, sculptures et dessins, et de nombreux documents, permettent de mesurer le chemin parcouru depuis la proclamation de ces audaces. Il apparaît aujourd'hui qu'elles ne se sont pas soustraites à une permanence plastique de bon aloi : les peintres futuristes sont d'abord des peintres ; le « faire » italien s'y distingue. C'est en vain qu'ils s'élèvent contre la culture classique. Ils sont conditionnés par un savoir séculaire, qu'ils enrichissent des recherches picturales de leur temps.

Celles-ci leur fournissent les moyens techniques d'exprimer la lumière et le mouvement. Le divisionnisme de Seurat, en particulier, permet la conversion des formes en vibrations lumineuses et en perceptions animées.

Le futurisme, qui doit tant au cubisme, s'oppose ici à lui. Alors que le cubisme, soucieux de constructivité, tente de rétablir un ordre classique par la recomposition synthétique des formes, le futurisme tend à un éclatement, traduisant des « états d'âme plastiques».

En raison même de la liberté et de la souplesse de l'expression verbale, Marinetti apparaît cependant plus affranchi du formalisme traditionnel que ceux qui le suivront picturalement.

Cet Italien si indéfectiblement attaché à son pays est, en outre, de culture cosmopolite. Né à Alexandrie, en Egypte, en 1876, il a accompli à Paris la majeure partie de ses études. Il s'exprime aussi bien en français qu'en italien. Sa tragédie « Le roi Bombance », publiée en 1905, a même été écrite dans notre langue, et n'a été traduite qu'ultérieurement en italien, sous le titre « Re Baldoria». Son œuvre littéraire est alors désordonnée, baroque, voire saugrenue, mais brillante et riche d'inventions. En fait, ce novateur apparemment brouillon est très informé des diverses tendances qui contestent la culture de son temps. Il n'ignore pas les essais « unanimistes» de Jules Romains, dont « L'âme des hommes» a paru en 1904.

Si l'on ne peut lui refuser la paternité d'un mouvement qu'il a eu le mérite de définir et d'animer chaleureusement, on peut considérer que, curieux de littérature française, il a dû connaître les textes précurseurs de ce qui sera le futurisme.

Or il ne les a jamais évoqués. Et en conséquence, le même silence a été observé par ses biographes, et par les historiens du futurisme.

Compte tenu de l'évolution technique, la précellence de l'automobile de course sur la «Victoire de Samothrace» a pourtant des précédents. Dès 1852 (année de l'établissement du Second Empire) Louis de Cormenin blâmait, dans « Les fleurs de la Science», les «poètes à courte vue» qui estimaient incompatibles le machinisme et le lyrisme. La machine, certes, est encore imparfaite, écrivait-il, mais attendez, « et la locomotive sera aussi belle que le quadrige d'Agamemnon ».

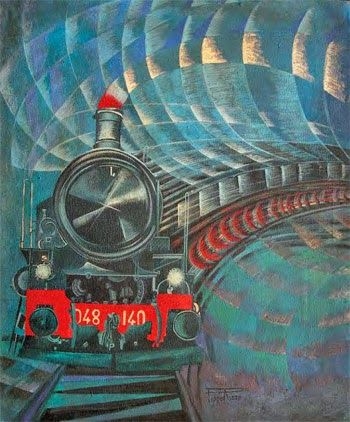

En 1853, la «Revue de Paris» entreprenait une campagne en faveur de l'introduction du monde mécanique dans les lettres et dans les arts. Louis Ulbach, Achille Kaufmann se distinguaient dans cette tentative. Kaufmann décrivait habilement, en peintre pourrait-on dire, les sensations visuelles d'un voyageur en chemin de fer. S'adressant aux hommes de lettres, il leur disait : « Si vous ne sentez pas alors le grandiose et la poésie de l'industrie, vous n'avez pas besoin de chercher ailleurs des inspirations, vous n'en trouverez nulle part».

Deux ans plus tard, Maxime Du Camp faisait paraître ses « Chants modernes», dont la préface constituait, plus d'un demi-siècle avant Marinetti, un véritable manifeste futuriste. Du Camp dénonçait l'attachement à un archaïsme gréco-latin. On s'occupe encore, écrivait-il, de la guerre de Troie et des Panathénées, en un siècle « où l'on a découvert des planètes et des mondes, où l'on a trouvé les applications de la vapeur, l'électricité, le gaz, le chloroforme, l'hélice, la photographie, la galvanoplastie...»

Cormenin, Ulbach, Kaufmann, Du Camp avaient d'ailleurs, en Angleterre, un illustre prédécesseur: William Wordsworth, mort en 1850, à quatre-vingts ans. « Les découvertes du chimiste, du botaniste ou du minéralogiste, avait-il dit, seront, pour l'art du poète, des objets aussi convenables que ceux sur lesquels il s'exerce actuellement».

Même un romancier tel que Jules Verne ne dédaignait pas de recourir au vocabulaire scientifique pour ses descriptions poétiques. Ainsi ce lever de soleil : « Le luminaire du jour, semblable à un disque de métal doré par le procédé Ruolz, monta de l'océan comme s'il sortait d'un immense bain voltaïque».

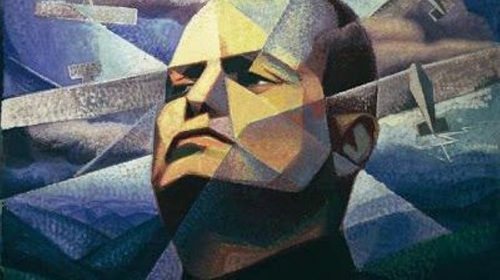

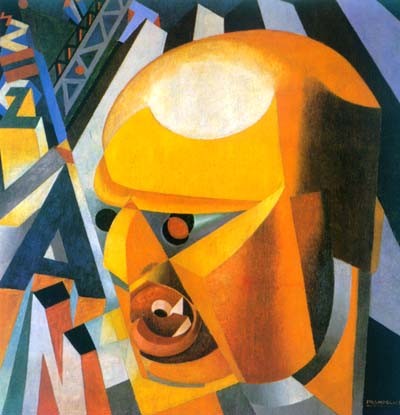

Parmi les artistes disposés à passer de la novation littéraire à la novation plastique, Umberto Boccioni va se révéler l'un des plus résolus. Lorsqu'il fait la connaissance de Marinetti, en 1909, l'année du premier manifeste, il s'est déjà livré à des recherches tendant à soustraire les arts aux disciplines académiques alors en faveur. D'abord séduit par le néo-impressionnisme et le « Modem style», il s'intéresse, dès 1911, au cubisme. Sculpteur autant que peintre, Boccioni publie en 1912 le « Manifeste technique de la sculpture futuriste».

Sa condamnation de l'exploitation du classicisme y est catégorique. Prétendre créer « avec des éléments égyptiens, grecs, ou hérités de Michel-Ange, est aussi absurde, assure-t-il, que de vouloir tirer de l'eau d'une citerne vide au moyen d'un seau défoncé».

Les tableaux actuellement exposés au « Musée national d'art moderne» démontrent l'efficacité de ses recherches quant à l'expression du mouvement. Sans aucune détermination précise des cavaliers et de leurs montures, sa «Charge des lanciers» impose le sentiment vertigineux d'une force convergeant irrésistiblement sur un même point.

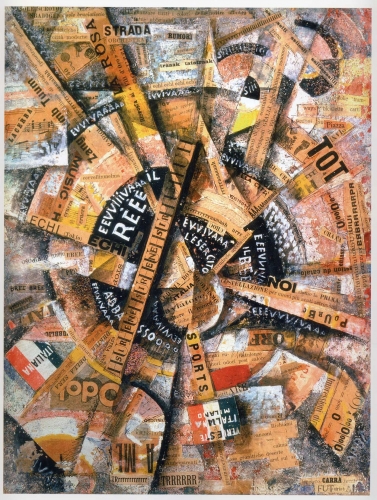

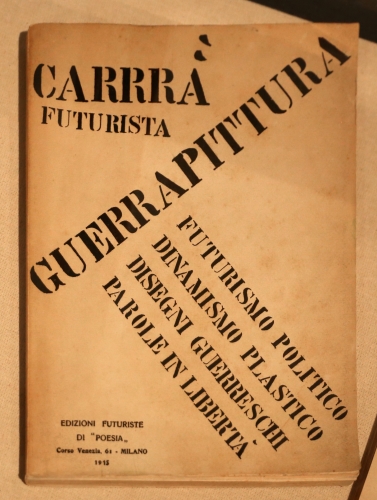

D'un tempérament moins doctrinaire que Boccioni, Carlo Carra prétendra avoir découvert la notion picturale du mouvement en se trouvant mêlé à une manifestation populaire. Sa fréquentation des milieux ouvriers, socialistes et anarchistes, contribuera évidemment à de telles découvertes.

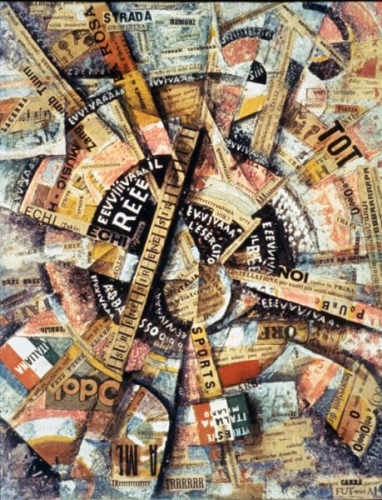

Il s'efforce cependant d'aller au-delà de la traduction du mouvement, et d'exprimer aussi les sons et les odeurs, afin d'obtenir une « peinture totale». Ses conceptions en cette matière sont pour le moins originales. « Nous n'exagérons guère, écrit-il en 1913, lorsque nous affirmons que les odeurs peuvent à elles seules déterminer dans notre esprit des arabesques de formes et de couleurs constituant le thème d'un tableau et justifiant sa raison d'être.»

« Les funérailles de l'anarchiste Galli», «Ce que m'a dit le tram», «Poursuite», présentés à Paris, sont des œuvres qui expliquent les aspirations de l'artiste. Carra y renoncera plus tard, après avoir rencontré Chirico, et pratiquera, au sein du groupe « Novecento », la peinture figurative qu'il avait dénoncée en sa jeunesse.

Luigi Russolo n'est pas seulement peintre, il est aussi, et avant tout sans doute, musicien. Aussi ne peut-on pratiquement pas isoler ses recherches plastiques de ses recherches musicales.

— Nous prenons infiniment plus de plaisir, a-t-il dit, à combiner idéalement des bruits de tramways, d'autos, de voitures et de foules criardes qu'à écouter encore, par exemple, l'« Héroïque» ou la « Pastorale».

La machine musicale (« Intonarumori ») que Russolo construisit, avec le peintre Ugo Piatti, n'apparut cependant pas convaincante. Après la guerre, où il fut blessé, son inventeur vint à Paris, où il se livra, lui aussi, à la peinture figurative.

Doyen des signataires des manifestes de 1910, Giacomo Balla aura été essentiellement peintre. Encore qu'il se soit formé à peu près seul, il fait toujours au début du siècle, figure de maître. Il compte parmi ses élèves Boccioni et Severini.

Ses études de la décomposition de la lumière et du mouvement doivent beaucoup au divisionnisme. Mais il se propose de donner à celui-ci un caractère plus général, et d'en faire, en quelque sorte, l'instrument d'une esthétique nouvelle.

Son « Lampadaire» a pour objet principal de « démontrer que le romantique clair de lune est écrasé par la lumière électrique moderne». Ses « interpénétrations» préfigurent les recherches d'abstraction géométrique.

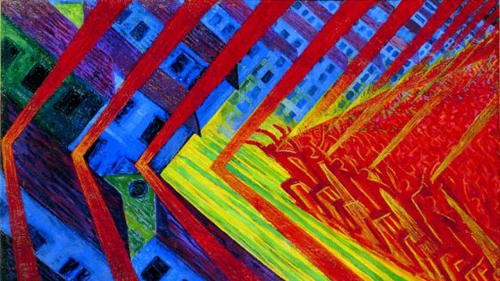

Si Gino Severini est, en France, le plus connu des artistes futuristes italiens, c'est qu'il s'établit très jeune à Paris, où il demeurera pratiquement pendant soixante ans. Compagnon d'Apollinaire, Max Jacob, Modigliani, Picasso, Braque, Delaunay, il épouse en 1913 la fille de Paul Fort.

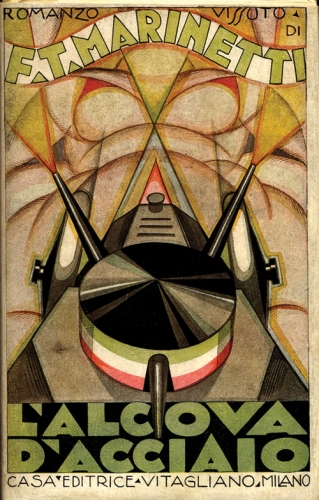

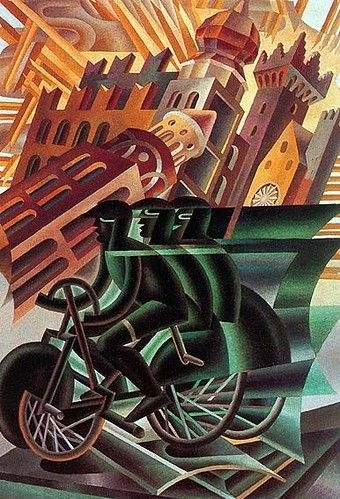

A ses débuts, la peinture de Seurat exerce sur lui une influence décisive. Mais très tôt il est acquis aux principes du futurisme, qui répond à ses goûts modernistes pour la machine et la vitesse, qui, croit-il, doivent permettre à l'homme de dominer la matière. Il va même jusqu'à s'initier au pilotage aéronautique.

Plusieurs de ses œuvres exposées ont été inspirées par la vie parisienne : « L'autobus», « La danse de l'ours au Moulin-Rouge», « Rythme plastique du 14 juillet», « Danseuse au bal Tabarin». L'artiste a lui-même expliqué le sens du tableau «Nord-Sud» qui figure à l'exposition : « l'idée de la vitesse avec laquelle un corps illuminé traverse des tunnels alternativement sombres et éclairés...».

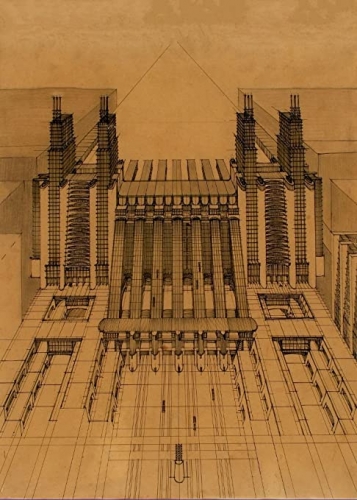

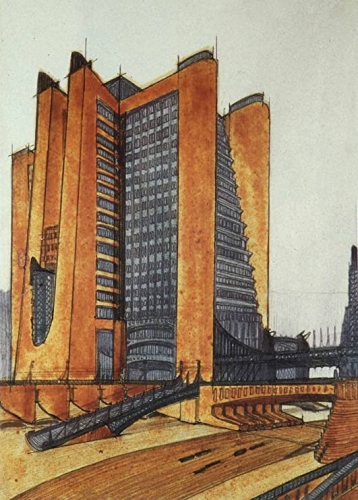

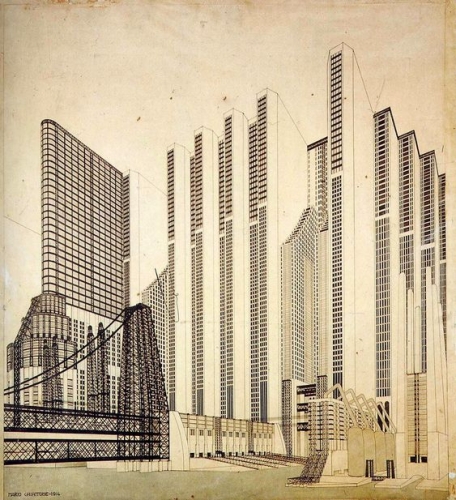

A ces cinq «grands» du futurisme, il faut ajouter Ardengo Soffici, écrivain autant que peintre, et l'architecte Antonio Sant'Elia, qui, soldat, fut tué en 1916, à vingt-sept ans. Un an plus tôt, Soffici avait déjà abandonné le groupe futuriste, en raison de ses dissentiments avec Marinetti.

La guerre, dont Marinetti magnifie les vertus régénératrices, sera donc fatale au futurisme italien proprement dit. Aux épreuves d'un conflit qui provoque des pertes irréparables, s'ajoutent des outrances de pensée et des intempérances de langage peu faites pour contribuer au crédit de cette école.

Ainsi, dans son « Manifeste futuriste de la luxure», publié en janvier 1913, Valentine de Saint-Point se livre à une apologie déréglée de la guerre. « La luxure, professe cette petite-nièce de Lamartine, est pour les conquérants un tribut qui leur est dû. Après une bataille où des hommes sont morts, il est normal que les victorieux, sélectionnés par la guerre, aillent, en pays conquis, jusqu'au viol pour recréer de la vie».

Sans doute Valentine de Saint-Point n'exprime-t-elle là que des considérations personnelles. C'est d'ailleurs une excentrique (vers la fin d'une carrière agitée, s'étant retirée en Egypte, elle se convertit à l'islamisme).

Pour avoir soutenu les futuristes avec un zèle jugé alors intempestif, Apollinaire, quant à lui, perdra en 1914 sa fonction de critique d'art à « l'Intransigeant» : « Vous vous êtes obstiné, lui écrit son directeur, Léon Bailby, à ne défendre qu'une école, la plus avancée, avec une partialité et une exclusivité qui détonnent dans notre journal indépendant... La liberté qu'on vous a laissée n'impliquait pas dans mon esprit le droit pour vous de méconnaître tout ce qui n'est pas futuriste».

Ce grief apparaît aujourd'hui d'autant plus singulier que Guillaume Apollinaire ne peut être tenu pour un champion inconditionnel des futuristes. S'il a été séduit par leur mouvement, il en a distingué les travers : « Ils se préoccupent avant tout du sujet, écrit-il en 1912. Ils veulent peindre des états d'âme. C'est la peinture la plus dangereuse qui se puisse imaginer...»

Sans le déclarer ouvertement, Apollinaire accorde plus de crédit au cubisme, qu'il comprend d'ailleurs assez mal, qu'au futurisme. Cependant, l'universalité de celui-ci le séduit. L'auteur de « L'hérésiarque» propose de soustraire le futurisme à son italianisme originel, et de « réunir sous ce nom tout l'art moderne», en tenant compte, bien entendu, des particularismes constitutifs.

Cette tentative de fondation d'une «Internationale culturelle» n'est pas sans intérêt, mais elle se trouve aussitôt désavouée par le fondateur du futurisme lui-même : Marinetti. Celui-ci considère que le futurisme ne doit pas se départir de son caractère national.

Sentiment incompréhensible à qui oublierait que le futurisme a été lancé pour « délivrer l'Italie de sa gangrène de professeurs, d'archéologues, de cicérones et d'antiquaires... L'Italie a été trop longtemps le grand marché des brocanteurs. Nous voulons la débarrasser des musées innombrables qui la couvrent d'innombrables cimetières».

En 1910, dans son « Discours futuriste aux Vénitiens», Marinetti se réfère au passé glorieux de la cité des Doges pour flétrir l'avilissement de sa population contemporaine :

« Vous fûtes autrefois d'invincibles guerriers et des artistes de génie, des navigateurs audacieux et de subtils industriels... Avez-vous donc oublié que vous êtes avant tout des Italiens ? Sachez que ce mot, dans la langue de l'Histoire, veut dire : constructeurs de l'Avenir...»

Et, après avoir évoqué les « héros de Lépante», Marinetti conclut en exhortant ses compatriotes à préparer « la grande et forte Venise industrielle et militaire qui doit braver l'insolence autrichienne sur la Mer Adriatique, ce grand lac italien».

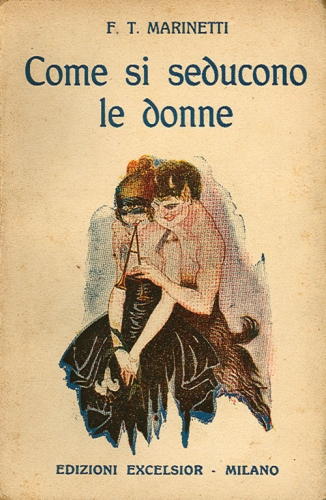

Déclaration belliciste qui rappelle que le futurisme n'est pas seulement un mouvement esthétique. Son caractère politique est attesté dès ses premières déterminations. Au neuvième paragraphe de son manifeste de 1909, Marinetti a proclamé : « Nous voulons glorifier la guerre (seule hygiène du monde), le militarisme, le patriotisme, le geste destructeur des anarchistes, les belles idées qui tuent, et le mépris de la femme»,

L'Italie de 1909 ne convient évidemment pas à l'application d'une telle doctrine. A la tête du gouvernement, Giovanni Giolitti pratique une politique de modération. Libéral et opportuniste, peu soucieux d'idéologie, mais attaché aux principes d'une gestion raisonnable des affaires publiques, il entend « donner satisfaction aux intérêts purement individuels et locaux». Il excelle à s'assurer une « clientèle». Salandra, qui lui succède à la veille de la Première Guerre mondiale, poursuit cette politique incolore.

Dans ce climat lénifiant, les futuristes ne paraissent que plus insolites. Depuis le début de l'année 1913, ils disposent cependant d'une revue, « Lacerba», dirigée par Giovanni Papini et Ardengo Soffici. Ce périodique atteint rapidement un tirage d'une vingtaine de milliers d'exemplaires. En raison même de sa dénonciation du régime «bourgeois», il est bien accueilli dans les milieux ouvriers, auxquels le programme futuriste doit pourtant paraître singulier.

En novembre 1914 paraît un nouveau journal «socialiste», qui dénonce l'attentisme du gouvernement et réclame l'intervention de l'Italie dans la guerre. Cet organe, « II popolo d'Italia», a pour animateur Benito Mussolini. En épigraphe, une citation de Napoléon : « La révolution est une idée qui a trouvé des baïonnettes». Son premier éditorial, signé Mussolini, se termine par ces mots : « Mon cri augural est un mot effrayant et fascinant : Guerre! »

A cinq ans de distance» la proclamation de Marinetti se trouve ainsi répétée, amplifiée par la réalité du conflit qui va bouleverser l'Europe.

Lorsque, en mars 1919, Mussolini crée le « Fascio », il reçoit naturellement l'adhésion de Marinetti.

Loin d'être scandaleux, le passage du futurisme au fascisme procède ainsi de la simple logique.

Aux diatribes des futuristes contre l'art académique, la littérature conventionnelle, l'enseignement traditionaliste, tout ce qui témoigne de la mort par sclérose d'une société, répond le chant allègre du Parti: Giovinezza («Jeunesse ») !

L'exposition du futurisme au « Musée d'art moderne» ne s'étend que sur une période de huit ans, de 1909 à 1916 : du premier manifeste de Marinetti à la mort de Boccioni et de Sant'Elia. L'époque du ralliement et celle qui lui a succédé, non seulement en Italie mais dans le monde, sont ainsi délibérément écartées.

Cependant, Marinetti n'est mort qu'en 1944, Russolo en 1947, Balla en 1958, Carra et Severini en 1966. Le futurisme, qui avait en quelque sorte assimilé les découvertes de l'impressionnisme, du pointillisme, du cubisme, devait féconder à son tour d'autres mouvements.

En Italie même, des artistes comme Prampolini, Martini, Depero, Sironi, Morandi, d'autres encore (et avec eux l'architecte Chiattone) ont maintenu, plus ou moins longtemps, la tendance futuriste.

En 1928, encore, le régime fasciste encourageait la « Première exposition d'architecture futuriste».

En Russie, où les novations culturelles occidentales étaient attentivement observées, Larionov, l'inventeur du « rayonnisme», reconnaissait dès 1913 ce qu'il devait au futurisme, au cubisme et à l'orphisme. Malévitch s'était inspiré très tôt, lui aussi, des principes de la nouvelle école italienne,

Gontcharova devait beaucoup à celle-ci, ainsi que l'atteste sa manière de provoquer le sentiment du mouvement par la décomposition des images.

Les œuvres de Mondrian, de Kandinsky, de jozef Peeters se réfèrent implicitement à « la splendeur géométrique et mécanique», et à la «sensibilité numérique» exaltées par Marinetti.

En Allemagne, l'influence du futurisme est sensible dans les œuvres de Meidner, Dix, Richter, Schad, etc.

Aux États-Unis, sur celles de Davies, Kuhn, Cramer, Kantov, Weber.

En Angleterre, le « vorticisme », fondé par Wyndham Lewis dès 1914, procède directement du futurisme. Ezra Pound, qui lui donna son appellation, l'a reconnu dans un propos dont la résonance va bien au-delà du particularisme vorticiste : « L'écrivain italien qui m'intéresse le plus aujourd'hui, et envers lequel je me sens une large dette de gratitude, est Marinetti. Marinetti et le futurisme ont donné un grand élan à toute la littérature européenne. Le mouvement qu'Eliot, Joyce, moi et d'autres avons lancé à Londres n'aurait pas existé sans le futurisme».

Maurice Cottaz

Sources: Le Spectacle du Monde – Novembre 1973

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

The Futurists were contemptuous of all tradition, of all that is past:

The Futurists were contemptuous of all tradition, of all that is past: