dimanche, 21 février 2021

Kondylis sur le conservatisme avec des notes sur la révolution conservatrice

Kondylis sur le conservatisme avec des notes sur la révolution conservatrice

Par Fergus Cullen

Ex : https://ferguscullen.blogspot.com

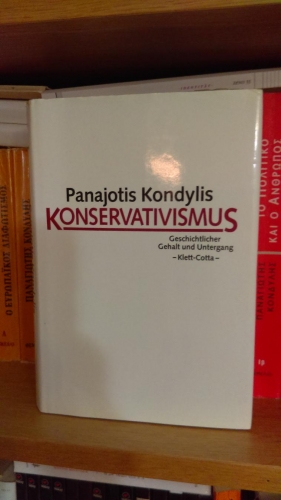

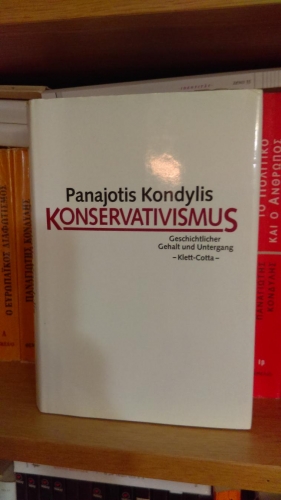

Notes sur Panagiotis Kondylis, "Le conservatisme comme phénomène historique".

C'est à ma connaissance le seul extrait substantiel du Konservativismus de Kondylis (paru à Stuttgart en 1986) disponible en anglais. La traduction est réalisée par "C.F." à partir de "Ὁ συντηρητισμὸς ὡς ἱστορικὸ φαινόμενο," Λεβιάθαν, 15 (1994), pp. 51-67, et reste inédite, mais consultable en ligne au format PDF. Les références des pages ci-dessous se rapportent à ce PDF. J'ai modifié très légèrement la traduction à certains endroits.

Kondylis vise à comprendre le conservatisme non pas comme une "constante historique" ou "anthropologique", mais comme un "phénomène historique concret" lié à un temps et à un lieu et donc coïncidant avec eux (pp. 1-2). Mais même ces études historicistes adoptent souvent une vision trop étroite, selon laquelle le conservatisme est une réaction contre, et donc un "dérivé" de la Révolution, ou, au mieux, contre le rationalisme des Lumières (pp. 2-3).

Kondylis conteste la conception, souvent conservatrice, du conservatisme comme expression de la "prédisposition naturelle [...] psycho-anthropologique" de l'"homme conservateur" à être "pacifique et conciliant" (pp. 5-6). Au contraire, le conservatisme et l'"activisme" sont parfaitement compatibles, comme le montre le droit féodal de résistance et de "tyrannicide", le soulèvement et la rébellion des aristocrates contre le trône" (pp. 7-8). Ce point contredit l'affirmation de Klemperer et d'autres selon laquelle l'activisme des révolutionnaires conservateurs est fondamentalement non conservateur.

"[L]a préservation et la culture de la tradition" en tant que "légitimation" des privilèges des nobles est l'expression de la volonté de ces nobles de se préserver et du "sentiment de supériorité" qu’ils éprouvaient. Kondylis postule une telle volonté universelle, au lieu d'une disposition conservatrice en guerre avec un "désir de renversement" révolutionnaire (du moins en ce qui concerne l'histoire des idées : pp. 8-9).

Kondylis conteste également la conception de soi ("image idéalisée") du conservateur comme traditionnaliste sans critique et sceptique à l’égard des "constructions intellectuelles", en se basant sur "l'impression erronée que la société prérévolutionnaire ne connaissait pas les idées et les idéologies, à la fois comme constructions intellectuelles systématiques et comme armes" (pp. 9-10). Les systèmes "théologiques" médiévaux sont les égaux des idéologies modernes en matière de "raffinement argumentatif", de "multilatéralisme systématique" et de "prétention à la "validité" universelle (ou "catholique")" (p. 10). Le conservatisme consiste à "reformuler" l'"idéologie légitimante de la societas civilis" en une "réponse" aux Lumières et à la Révolution (p. 10-1).

La modernité, pour Kondylis, se réalise en partie par une "activité idéologique vivante", non pas comme résultat de la "constitution anthropologique" de certaines personnes (disposition intellectuelle), mais comme expression de leur volonté fondamentale d'auto-préservation, qui, étant donné leur "manque de pouvoir social important devait être contrebalancé par leur prééminence sur le front intellectuel" ; et ainsi les conservateurs ont répondu en nature (polémique, théorie, etc.). Les partisans de la modernité ("ennemis de la domination sociale de l'aristocratie héréditaire") ont fait le premier pas crucial dans le discours politique au sens moderne, et ont ainsi été "beaucoup plus intensément réflexifs", tout comme le conservatisme est généralement censé l'être (pp. 11-2).

Cette "importance de la théorie parmi les armes de l'ennemi" est également à l'origine de la "répugnance purement polémique" du conservatisme pour l'intellectualité (p. 12). Non seulement l'anti-intellectualisme déclaré du conservatisme doit être considéré comme suspect, mais dans certains cas intrigants, il doit être compris comme une sorte de démonstration d'une compréhension théorique du rôle de la théorie (de l'intellectualité) dans le "Progrès" ("Déclin"). Comme le dit Kondylis, "seule la théorie permet de décrire idéalement une société "saine" et "organique", qui n'est pas créée par des théories abstraites et n'en a pas besoin" (p. 13).

Cette "hésitation et indécision" du conservatisme concernant l'intellectualité, la "raison", etc. (c'est-à-dire cette apparente tension performative - si ce n'est pas une contradiction -, ambiguë), reflète la tension dans l'intense ratiocination de la théologie médiévale pour montrer les limites de la raison humaine, ou du sentimentalisme des Lumières ou de la Lebensphilosophie moderne pour placer l'instinct au-dessus de l'intellect (p. 13). Cette "indécision" (un mot révélateur, si l'on se souvient des contributions de Kondylis au décisionnisme) et le manque de systématisation et la variété prolifique de la pensée conservatrice qui l'accompagnent sont "naturels" pour "toutes les grandes idéologies politiques - et pas seulement politiques" (p. 13-4 ; voir la deuxième partie ici).

"[C]ommonplace of conservative self-understanding and self-presentation have crept [...] into the scientific discussion," such as "the coquettish enmity of conservatives towards theory." (« Le sens commun propre à l’auto-définition et à l’auto-représentation conservatrices s’est insinué (…) dans la débat scientifique, ainsi que l’hostilité, toute de coquetterie, des conservateurs à l’endroit de la théorie » (p. 13-4 ; voir la deuxième partie ici). La priorité du "concret" sur l'"abstrait" est elle-même, ou repose sur, une abstraction (p. 15).

Kondylis dichotomise les politiques "conservatrices" et "révolutionnaires" (p. 17).

L'adaptation prudente et sagace aux circonstances et aux conditions, dont les conservateurs sont si fiers, se fait en règle générale sous la pression de l'ennemi" ; l'ennemi "pousse les conservateurs à adopter une attitude défensive ou bon enfant et facile à vivre" ; "les conservateurs découvrent leur sympathie pour le "vrai" progrès et [...] parlent du développement organique dynamique [...] de la société et de l'histoire" (p. 18). Les conservateurs sont obligés de faire certaines concessions à la modernité. Pour anticiper un peu mes propres arguments : le conservatisme révolutionnaire est une concession, mais, en gros, à la forme et non au contenu de la modernité. C'est-à-dire que le révolutionnaire conservateur accepte, doit accepter, l'industrialisation, la dissolution de la "société organique", l'instrumentalisation de l'homme, le discours laïque comme espace du discours politique (même religieux), la "médiatisation", la communication de masse, etc. et souhaite les mettre au service des principes "conservateurs", "de droite" : c'est-à-dire des abstractions des expressions concrètes qui ont donné naissance au conservatisme.

Parfois, les principes conservateurs sont, ou semblent être, exprimés concrètement sans effort conservateur, ou à la suite de l'effort de "l'ennemi" qui, "en luttant pour la consolidation de sa propre domination, se soucie ou est concerné par le respect du droit, de la hiérarchie et de la propriété (légalement ou en réalité sauvegardée et protégée) - bien sûr, avec des signes différents et avec des contenus différents" (p. 20). Un "conservatisme" libéral ou démocratique, bourgeois ou prolétarien, peut se former sur cette base, opposé, semble-t-il en règle générale, à la révolution conservatrice (la bifurcation de la R.C. et du "simple conservatisme").

Tant les conservateurs que les révolutionnaires postulent des lois "naturelles" ou une condition "naturelle" de l'homme ; mais tous deux s'efforcent de répondre, dans le cas conservateur, au développement apparemment naturel de conditions contre-nature (Révolution, "Progrès", "Déclin"), ou, dans le cas révolutionnaire, à la primauté apparente de conditions contre-nature (inégalité, exploitation, etc. : p. 21). Nous pourrions ajouter que le révolutionnaire s'efforce également de répondre à la question de savoir comment, comme le suggère le paragraphe précédent, ses propres efforts semblent non seulement conduire à de telles conditions, mais aussi instancier, exprimer concrètement, les principes de son ennemi, le conservateur. Nous abordons ici la théodicée.

Sur le modèle de Kondylis, le conservatisme est l'expression idéologique des privilèges de la noblesse et de "la résistance de la societas civilis contre sa propre décomposition" : contre la montée de la bourgeoisie, du rationalisme des Lumières, de la démocratisation, etc., se terminant apparemment par "la mise à l'écart de la primauté de l'agriculture par la primauté de l'industrie" ; ensuite "on ne peut parler de conservatisme que métaphoriquement ou avec une intention polémique-apolitique" (pp. 22-3). Schéma : conservatisme - libéralisme - socialisme, dans lequel chacun surmonte le terme précédent pour aboutir à une postmodernité douteuse dans laquelle "chaque [concept] passe ou se confond avec un autre, et aucun d'eux n'est précis", indiquant "que la fin de cette époque historique, dont ils ont partiellement ou totalement tiré le contenu de la vie sociopolitique et intellectuelle, est en partie de plus en plus proche, et en partie déjà arrivée" (p. 23).

La raison pour laquelle on peut affirmer qu'il existe un courant conservateur-révolutionnaire au sein de cette postmodernité confuse dans ses catégories, et donc pas encore tout à fait ‘’navigable’’, est que quelque chose, une nouvelle (proto-) catégorie, émerge effectivement de et en tandem avec les premières secousses prémonitoires de la postmodernité (industrialisation et démocratie de masse : la fin du XIXe et le début du XXe siècle, avec la Grande Guerre comme premier d'une série de ‘’bassins versants’’). A savoir, une radicalisation et une abstraction consciente ou subconsciente des principes conservateurs, au service desquels sont mis certains aspects de la modernité tardive (voir ci-dessus).

12:15 Publié dans Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, philosophie politique, panajotis kondylis, théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques, conservatisme, conservatisme révolutionnaire, révolution conservatrice |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 25 novembre 2020

Kondylis on Conservatism with Notes on Conservative Revolution

Kondylis on Conservatism with Notes on Conservative Revolution

Fergus Cullen

Ex: https://ferguscullen.blogspot.com

Notes on Panagiotis Kondylis, “Conservatism as a Historical Phenomenon.” This is to my knowledge the only substantial excerpt from Kondylis’ Konservativismus (Stuttgart, 1986) available in English. The translation is by “C.F.” from “Ὁ συντηρητισμὸς ὡς ἱστορικὸ φαινόμενο,” Λεβιάθαν, 15 (1994), pp. 51–67, and remains unpublished, but discoverable in PDF format online. Page references below are to that PDF. I have altered the translation very slightly in some places.

Kondylis aims to understand conservatism not as a “historical” or “anthropological constant,” but as a “concrete historical phenomenon” bound to, and thus coterminous with, a time and a place (pp. 1–2). But even such historicist scholarship often takes too narrow a view, according to which conservatism is a reaction against, and thus “derivative” of, the Revolution, or, at best, against Enlightenment rationalism (pp. 2–3).

Kondylis disputes the conception, often a conservative self-conception, of conservatism as an expression of the “natural […] psychological-anthropological predisposition” of “conservative man” to be “peace-loving and conciliatory” (pp. 5–6). On the contrary, conservatism and “activism” are perfectly compatible, as the “feudal right of resistance and ‘tyrannicide,’ the uprising and rebellion of aristocrats against the throne” shows (pp. 7–8). This is a point against the claim by Klemperer and others that the activism of Conservative Revolutionists is fundamentally unconservative.

“[L]ove and cultivation of tradition” as a “legitimation” of noble privileges is an expression of those nobles’ will to self-preservation and “sense of superiority.” Kondylis posits such a universal will, in place of a conservative disposition at war with a revolutionary “urge to overthrow” (at least as concerns the history of ideas: pp. 8–9).

Kondylis also disputes the self-conception (“idealised image”) of the conservative as uncritically traditionalist and sceptical of “intellectual constructions,” based upon “the erroneous impression that pre-revolutionary societas civilis did not know of ideas and ideologies, both as systematic intellectual constructions and as weapons” (pp. 9–10). Mediaeval “theological” systems are the equals of modern ideologies in “argumentative refinement,” “systematic multilateralism” and “pretension to universal” (or “catholic”) “validity” (p. 10). Conservatism consists in the “reformulation” of the “legitimising ideology of societas civilis” into an “answer” to the Enlightenment and Revolution (pp. 10–1).

Modernity, for Kondylis, comes about, in part through “lively ideological activity,” not as a result of the “anthropological constitution” of certain persons (intellectual disposition), but as an expression of their basic will to self-preservation, which, given their “lack of weighty social power had to be counterbalanced by their pre-eminence on the intellectual front”; and so conservatives responded in kind (polemic, theory, etc.). The partisans of modernity (“foes of the social dominance of the hereditary aristocracy”) made the first crucial step into political discourse in the modern sense, and were thus “much more intensively reflexive,” just as conservatism is generally purported to be (pp. 11–2).

This, “the importance of theory among the foe’s weaponry,” is also the origin of conservatism’s “purely polemical abhorrence” for intellectuality (p. 12). Not only should conservatism’s professed anti-intellectualism be taken as suspect; but in certain intriguing cases, it should be understood as a sort of demonstration of a theoretical understanding of theory’s (intellectuality’s) role in “Progress” (“Decline”). As Kondylis says: “only theoretically could the idealised description of a ‘healthy’ and ‘organic’ society be made which is not created by abstract theories, nor does it need them” (p. 13).

This “vacillation and indecisiveness” of conservatism re. intellectuality, “Reason,” etc. (i.e. this apparent performative—if not contradiction then—tension, ambiguity), mirrors the tension in the intense ratiocination by Mediaeval theology to show the limits of man’s reason, or by Enlightenment sentimentalism or modern Lebensphilosophie to set instinct above intellect (p. 13). This “indecisiveness” (a telling word, when one recalls Kondylis’ contributions to décisionnisme) and the accompanying unsystematicity and proliferous variety of conservative thought is “natural” to “all the great political—and not only political—ideologies” (pp. 13–4; see part 2 here).

“[C]ommonplaces of conservative self-understanding and self-presentation have crept […] into the scientific discussion,” such as “the coquettish enmity of conservatives towards theory.” The prioritization of the “concrete” over the “abstract” is itself, or relies upon, an abstraction (p. 15).

“[C]ommonplaces of conservative self-understanding and self-presentation have crept […] into the scientific discussion,” such as “the coquettish enmity of conservatives towards theory.” The prioritization of the “concrete” over the “abstract” is itself, or relies upon, an abstraction (p. 15).

Kondylis dichotomizes “conservative” and “revolutionary” politics (p. 17).

“Prudent and sagacious adaptation to circumstances and conditions, of which conservatives are so proud, is carried out as a rule under the foe’s pressure”; the foe “pushes conservatives to adopt a defensive or good-natured and easy-going stance”; “conservatives discover their sympathy for ‘true’ progress, and […] talk of the dynamic organic development […] of society and of history” (p. 18). Conservatives are compelled to make certain concessions to modernity. To anticipate my own arguments a bit: revolutionary conservatism is a concession, but, loosely speaking, to the form and not the content of modernity. That is, the conservative revolutionary accepts, must accept, industrialisation, the dissolution of “organic society,” the instrumentalisation of man, secular discourse as the space of (even religious) political discourse, “mediatisation,” mass communication, etc., and wishes to put these at the service of “conservative,” “rightist” principles: that is, abstractions from the concrete expressions that gave birth to conservatism.

Sometimes conservative principles are, or seem to be, expressed concretely without conservative effort, or as a result of “the foe’s” effort, who, “by struggling for the consolidation of his own domination, cares for, or is concerned with, compliance with law, with hierarchy and with property (legally or in actual reality safeguarded and protected)—of course, with different signs and with different content” (p. 20). A liberal or democratic, bourgeois or proletarian “conservatism” can form on this basis, opposed, it would seem as a general rule, by conservative revolution (the bifurcation of C.R. and “mere conservatism”).

Both conservatives and revolutionaries posit “natural” laws or a “natural” condition of man; but both struggle to answer, in the conservative case, the apparently natural development of unnatural conditions (Revolution, “Progress,” “Decline”), or, in the revolutionary case, the apparent primordiality of unnatural conditions (inequality, exploitation, etc.: p. 21). We might add that the revolutionary also struggles to answer how, as suggested in the previous paragraph, his own efforts seem to not only lead to such conditions but instantiate, express concretely, his enemy’s, the conservative’s, principles. Here we approach theodicy.

On Kondylis’ model, conservatism is the ideological expression of noble privilege and of “the resistance of societas civilis against its own decomposition”: against the rise of the bourgeoisie, Enlightenment rationalism, democratisation, etc., apparently ending with “the sidelining of the primacy of agriculture by the primacy of industry”; thereafter “there can be talk of conservatism only metaphorically or with polemical-apologetic intent” (pp. 22–3). Schema: conservatism — liberalism — socialism, in which each overcomes the prior term to culminate in a questionable postmodernity in which “every [concept] passes over into, or merges with, another, and none of them are precise,” indicating “that the end of that historical epoch, from whose social-political and intellectual life they partially or wholly drew their content, is, in part, near and approaching, and has, in part, already come” (p. 23).

The reason to posit a conservative-revolutionary current within this categorially confused, and thus not yet quite navigable, postmodernity is that something, a new (proto-) category, does emerge out of and in tandem with the first warning tremors postmodernity (industrialisation and mass democracy: the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, with the Great War as the first in a series of watersheds). To wit, a conscious or subconscious radicalisation and abstraction of conservative principles, at whose service certain aspects of late modernity are put (see above).

00:47 Publié dans Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : panajotis kondylis, conservatisme, révolution conservatrice, allemagne, philosophie, philosophie politique, politologie, sciences politiques, théorie politique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 07 février 2020

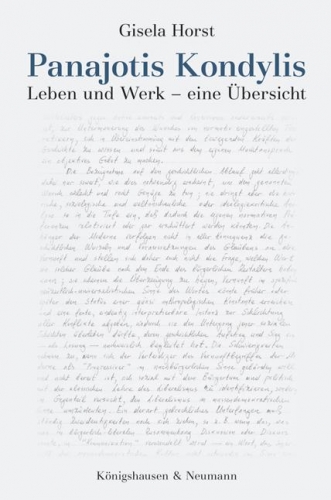

Gisela Horst Panajotis KondylisLeben und Werk – eine Übersicht

Gisela Horst

Panajotis KondylisLeben und Werk – eine Übersicht

564 Seiten | Broschur | Format 15,5 × 23,5 cm

Epistemata Philosophie, Bd. 605

€ 58,00 | ISBN 978-3-8260-6817-1

Dieses Buch enthält erstmals umfangreiche biografische Daten des Philoso-phen und Ideengeschichtlers Panajotis Kondylis (1943–1998) und einen in-haltlichen Überblick über sein umfangreiches Werk. – Kondylis promovierte in Heidelberg und verfasste bedeutende geistesgeschichtliche Standardwerke zum Konservativismus, zur europäischen Aufklärung, zur Dialektik, zur Mas-sendemokratie und zur Metaphysikkritik, und er bezog als Autor Stellung zum politisch-sozialen Zeitgeschehen. Sein Beitrag zur Philosophie besteht in anthropologischen Grundeinsichten, die in Macht und Entscheidung und Sozialontologie entwickelt werden. Er lieferte zwei Beiträge zum histori-schen Lexikon Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe und war Träger von Ehrungen und Preisen, u.a. erhielt er den Wissenschaftspreis der Humboldtstiftung, war Fellow des Berliner Wissenschaftskollegs und Träger der Goethemedaille.Die AutorinGisela Horst (geb. 1946) kennt Kondylis aus persönlichen Gesprächen; nach Ende ihrer beruflichen Tätigkeit als Naturwissenschaftlerin studierte sie Lite-ratur- und Geschichtswissenschaft an der Fernuniversität in Hagen und ver-fasste dort eine Dissertation zu Leben und Werk von P. Kondylis bei Prof. Dr; Peter Brandt

Dieses Buch enthält erstmals umfangreiche biografische Daten des Philoso-phen und Ideengeschichtlers Panajotis Kondylis (1943–1998) und einen in-haltlichen Überblick über sein umfangreiches Werk. – Kondylis promovierte in Heidelberg und verfasste bedeutende geistesgeschichtliche Standardwerke zum Konservativismus, zur europäischen Aufklärung, zur Dialektik, zur Mas-sendemokratie und zur Metaphysikkritik, und er bezog als Autor Stellung zum politisch-sozialen Zeitgeschehen. Sein Beitrag zur Philosophie besteht in anthropologischen Grundeinsichten, die in Macht und Entscheidung und Sozialontologie entwickelt werden. Er lieferte zwei Beiträge zum histori-schen Lexikon Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe und war Träger von Ehrungen und Preisen, u.a. erhielt er den Wissenschaftspreis der Humboldtstiftung, war Fellow des Berliner Wissenschaftskollegs und Träger der Goethemedaille.Die AutorinGisela Horst (geb. 1946) kennt Kondylis aus persönlichen Gesprächen; nach Ende ihrer beruflichen Tätigkeit als Naturwissenschaftlerin studierte sie Lite-ratur- und Geschichtswissenschaft an der Fernuniversität in Hagen und ver-fasste dort eine Dissertation zu Leben und Werk von P. Kondylis bei Prof. Dr; Peter Brandt

00:53 Publié dans Livre, Livre, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : panajotis kondylis, livre, hommage, philosophie, philosophie politique, théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 21 juin 2019

Panajotis Kondylis: Ein skeptischer Aufklärer

Panajotis Kondylis: Ein skeptischer Aufklärer

00:05 Publié dans Philosophie, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : panajotis kondylis, philosophie, philosophie politique, sciences politiques, politologie, théorie politique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Kennzeichnend für das Werk des verstorbenen griechischen Gelehrten, der in Heidelberg ein großes Stück seiner Lebenszeit verbrachte und der meist auf Deutsch seine begrifflichen Entwürfe ausführte, war sein auf Machtansprüche bezogener interpretativer Ausgangspunkt. Im Gegensatz zu anderen dem Moralisieren zugeneigten Ideen- und Sozialhistorikern hat Kondylis nie für das „Gute“ gekämpft. Zwar von der Aufklärung geprägt, hat Herausgeber Falk Horst recht, wenn er von einem Aufklärer ohne Mission spricht.

Kondylis zergliedert aufeinanderfolgende Weltanschauungen ausgehend vom Mittelalter, aber er packte seine Aufgabe möglichst wertfrei an. Er bezeichnete diese Herangehensweise als „deskriptiven Dezisionismus“, den er von wertbezogenen Auffassungen menschlicher Entscheidungen und Ansprüche abhebt. Und er benennt die Wissenschaftlichkeit, die er in seinen zur Reife gelangten Büchern verfolgt, als „Sozialontologie“.

In erster Linie ein Sozialwesen

Kondylis geht von der Grundannahme aus, dass das menschliche Wesen nicht von einer bestimmten Sozialbeziehung loszutrennen sei. Von seinem Standpunkt her ist der Mensch in erster Linie Sozialwesen, dessen Verhältnis zu Mitmenschen und zur Außenwelt durch seine Stelle in einer vorgegebenen Rangordnung zu berücksichtigen sei.

Zuallererst kümmert man sich um die Selbsterhaltung, die die Mitwirkung anderer voraussetzt und dann darum, seine Nische gegen Kontrahenten zu verteidigen. In seinem schmalen Band Macht und Entscheidung. Die Herausbildung der Weltbilder und die Wertfrage (1984) nimmt Kondylis die kämpferische und machtstrebende Seite von zwischenmenschlichen Wechselwirkungen in den Blick.

Moralismus oder Nihilismus

Grundlegend für seine seitenreichen Bücher über die Aufklärung, den klassischen Konservatismus und das Zeitalter der planetarischen Politik ist seine Inanspruchnahme einer machtorientierten Auslegungsperspektive. Auch bei gelehrten Auseinandersetzungen und streng herausgebildeten theoretischen Arbeiten lässt sich so eine alle Anliegen prägende Kampfgesinnung feststellen. Der Wissenschaftler stellt seine These derjenigen seines Kontrahenten entgegen.

Die Aufklärungsdenker legten es darauf an, Natur und Sinnlichkeit gegen eine mittelalterliche Denkart geltend zu machen. Doch die ehemaligen Beteiligten gingen getrennte Wege, als die Frage aufkam, ob der Kampf gegen die verworfene Metaphysik in einer normativen Sittlichkeit oder in einem alles zerlegenden Nihilismus münden sollte. In zwei gegensätzliche Denkgruppen zerteilten sich die Aufklärer, die Verfechter einer Vernunftsmoralität wie Kant und Voltaire und nihilistische Materialisten wie Holbach und La Mettrie.

Die bürgerliche Gesellschaft, die die Kulturwelt der Aufklärung hochhielt, mußte einen Zweifrontenkrieg gegen den Konservatismus führen, der die Ideale einer vormodernen Sozialordnung wieder zur Geltung bringen wollte, und gegen die Massendemokratie, die für die Gleichheit und Austauschbarkeit der Menge eintritt. Ohne diese dialektische, kämpferische Stoßrichtung zu betrachten, meint Kondylis, sind aufeinanderfolgende Herrscherklassen und führende Ideologien kaum zu begreifen. Nur im Hinblick auf ein Gegenüber entwickelt sich der Einzelne gemeinschaftlich, seinsartig und begrifflich heraus.

Die Sozialontologie und Sozialanthropologie von Kondylis wird normalerweise als eine einfallsreiche Verschmelzung der Gedanken Marxens und Carl Schmitts interpretiert. Verblüffend mag es sein, dass Kondylis Marx, aber bei weitem weniger Schmitt, als Vordenker anerkannte. Ebenso großzügig gestand er Reinhart Koselleck, mit dem er einen langjährigen Briefwechsel unterhielt, und seinem Doktorvater aus Heidelberg, Werner Conze, eine Einwirkungsrolle bei seiner Ideenwelt zu. Zusätzlich erwähnt er Spinoza, dessen-theologisch-politischer Traktat seinen Machtbegriff mitgestaltete.

Warum aber ging Kondylis mit Schmitt, dessen Freund-Feind-Denken er teilt, fast stiefmütterlich um? Mag sein, dass Kondylis die Originalität seiner Begriffe unterstreichen wollte. Ebenso relevant, wie Horsts Sammelband klarmacht, wurde Kondylis zu seiner Jugendzeit radikalisiert, als er gegen die Regierung der Obristen in seinem griechischen Stammland aufgemuckt hatte.

Auf diese Jugendjahre ist die marxistische Prägung zurückzuführen, auch wenn der ausgereifte Denker kaum als Marxist oder als links orientiert einzustufen war. Die Fokussierung auf Geschichtsabläufe und sozial bedingte Leitkulturen weisen auf marxistisch angehauchte Schwerpunkte zurück. Klar ist aber, daß Kondylis wie Koselleck und andere führende deutsche Ideenhistoriker aus der zweiten Hälfte des letzten Jahrhunderts von Schmitt beeinflusst wurden.

Daß Kondylis mit einem einspurigen oder übermäßig vereinfachenden Weltbild hantierte, ist eine geläufige Kritik an seiner anthropologischen und politischen Perspektive, die sich um die Selbsterhaltung und das Machtstreben des sozial angesiedelten Einzelnen dreht. Aber das setzt voraus, daß der Sozialforscher Kondylis ein Gesamtbild des politischen, gemeinschaftlichen und ideentheoretischen Handelns liefern wollte. Stattdessen kann sein Gedankengut herangezogen werden, um das menschliche Verhalten zu beleuchten und Erkenntnis über die menschliche Motivation in einzelnen Situationen abzugeben.

Kein Optimist

Bei all seiner Anhänglichkeit an die Aufklärung und die dazugehörigen Einsichten hat Kondylis keinesfalls das optimistische Zukunftsbild vertreten, das den Rationalismus des achtzehnten Jahrhunderts prägte. Er zählte zur Gesellschaft, die Zeev Sternhell und Isaiah Berlin als „les Contre-lumières” charakterisierten und die angeblich nichts Gutes im Schilde führten. Diese Grübler setzen die kritische Verfahrensweise der Aufklärung ein, um ihre Endvision zu hinterfragen und sogar zu entwerten.

Anders gesagt: Kondylis verstand seinen Lehrauftrag anders als die von ihm bespöttelten Moralisten. Außer dem Entscheidungstreffen sozial verorteter und motivierter Einzelner und Gruppen, die im Spannungsfeld mit anderen ähnlich bestimmten Wesen handeln, kann uns Kondylis kein Welt- oder Zukunftsbild anbieten. Zu seiner Ehre mahnt er vor den Schönfärbern, die unsere Freiheit wie unsere Nüchternheit abschaffen wollen.

Aus dem Kreis der BN-Autoren hat sich insbesondere Felix Menzel mit Kondylis beschäftigt und ein Zitat aus Macht und Entscheidung seiner Alternativen Politik vorangestellt.