Vor mir liegt ein frisch gedrucktes Büchlein, das mich wieder daran erinnert, was für eine große geistige Freude das „Rechtssein“ machen kann. Fast hätte ich es schon vergessen. Aber irgendeinen guten Grund muß ein Mensch ja haben, warum er sich all den Ärger antut, der damit einhergeht, nicht im linken Schafswolfsrudel mitzuheulen bzw. zu -blöken.

Vor mir liegt ein frisch gedrucktes Büchlein, das mich wieder daran erinnert, was für eine große geistige Freude das „Rechtssein“ machen kann. Fast hätte ich es schon vergessen. Aber irgendeinen guten Grund muß ein Mensch ja haben, warum er sich all den Ärger antut, der damit einhergeht, nicht im linken Schafswolfsrudel mitzuheulen bzw. zu -blöken.

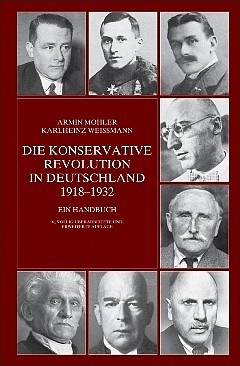

Die Rede ist von dem Kaplaken-Band „Notizen aus dem Interregnum“ [2], der dreizehn Kolumnen versammelt, die Armin Mohler [3] im Laufe des Jahres 1994 für die damals noch junge Junge Freiheit schrieb. Diese war eben auf das wöchentliche Format umgestiegen, und stand am Anfang ihres Siegeszuges als wichtigstes Organ und Sammelbecken der deutschen Rechten und Konservativen. Letzteres sind Begriffe, die Mohler meistens synonym oder alternierend gebrauchte, auch wenn es viele Rechte gibt, die sich nicht als „konservativ“ und viele Konservative, die sich nicht als „rechts“ betrachten. Außerhalb ihrer Milieus interessiert das allerdings bekanntlich keine Sau.

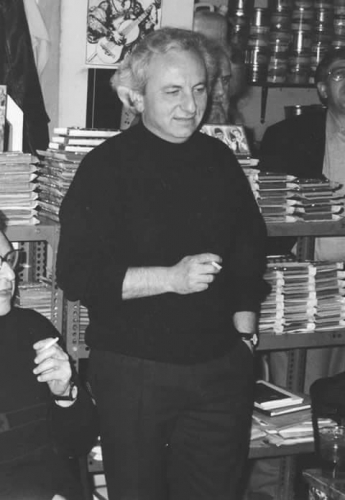

Die „Notizen“ sind, wie Götz Kubitschek im Nachwort formuliert, in einem „didaktisch-drängenden Ton“ verfaßt. Der 74jährige Mohler, einer der bedeutendsten Köpfe des deutschen Nachkriegskonservatismus, wollte mit seinen Kolumnen eine Art Orientierungshilfe, einen „Crash-Kurs“ im „Rechtssein“ bieten. So behandelte er noch einmal die Begriffe und Positionen, die in seinem Werk immer wiederkehren. Seine zentrale Formel war diese:

Bekannt ist der kokette Spruch: Wer nicht einmal links (oder wenigstens liberal) war, der wird kein richtiger Rechter. Der Schreibende hat jedoch Freunde, auf die das nicht zutrifft. Er sagt darum lieber: ein Rechter wird man durch eine Art von »zweiter Geburt«. Man hat sie durchlebt, wenn man sich – der eine früher, der andere später – der Einsicht öffnet, daß kein Mensch je die Wirklichkeit als Ganzes zu verstehen, zu erfassen und zu beherrschen vermag. Diese Einsicht stimmt manchen melancholisch, vielen aber eröffnet sie eine wunderbare Welt. Jedem dieser beiden Typen erspart sie, sein Leben mit Utopien, diesen Verschiebebahnhöfen in die Zukunft zu verplempern.

Das leuchtet wohl jedem unmittelbar ein, der die Erfahrung gemacht hat, daß eine zu eng gefaßte Weltanschauung blind für die Wirklichkeit machen kann, die nach einem Wort von Joachim Fest „immer rechts steht“. Ein Gitter von Abstraktionen verhindert, daß man sie sieht, wie sie ist (insofern man das eben mit seinen – stets beschränkten – Mitteln kann), daß man ihre Komplexität und Widersprüchlichkeit wahrnimmt und akzeptiert. (Damit ist aber nicht die typisch linke Rede von der „Komplexität“ gemeint, die genau auf das Gegenteil abzielt, nämlich eine Wahrnehmungschwäche kaschiert und sich um eine Entscheidung drücken will.)

Der von Mohler hochgeschätzte österreichische Schriftsteller Heimito von Doderer sprach an dieser Stelle gerne griffig von den „All-Gemeinheiten“ und von der „Apperzeptionsverweigerung“, einer nicht selten willentlichen Blockierung der Wahrnehmung, die zunächst zur Verdummung und schließlich gar zum Bösen führe.

Mohler kannte den Begriff der „political correctness“ noch nicht – aber es handelt sich hierbei um genau die Art von Abstraktionengitter, die er sein Leben lang bekämpfte. „Political correctness“ stellt zuerst ein Ideal auf, wie die Realität sein sollte, führt alsdann zu ihrer Leugnung (nach Doderer das „Dumme“), ob aus Angst (Doderer sprach vom „Kaltschweiß der Lebensschwäche“) oder aus Wunschdenken oder aus Opportunismus oder aus ideologischer Verblendung; dann aber zu unerbittlichen Verfolgung (nach Doderer wäre dies dann das „Böse“) all jener, die immer noch sehen und immer noch benennen,was sie eigentlich gar nicht sehen dürfen, etwa, daß der Kaiser nackt ist .

Auch das eng mit der „political correctness“ verbundene Gleichheitsdenken ist so eine Scheuklappe und „All-Gemeinheit“. In Notiz 7 (15. April 1994) diskutiert Mohler den italienischen Politologen Norberto Bobbio, der die Formel aufstellte, daß die Rechte vor allem mit dem beschäftigt sei, was die Menschen unterscheidet, und die Linke, mit dem, was die Menschen einander angleicht. Das geht soweit, daß der Linke die Gleichheit mit Gerechtigkeit gleichsetzt und zum absoluten moralischen Gut erhebt – die Menschen sollen „vernünftigerweise lieber gleicher als ungleich sein“. Der Rechte dagegen bejaht die Ungleichheit, die es ja nur als relativen Begriff gibt. Erst die Ungleichheit gibt dem Leben seine Spannung, Vielfältigkeit und Farbe.

Die Absage an die prinzipielle „Durchschaubarkeit“ und daher „Machbarkeit“ aller Dinge ist kein Aufruf zum Nichthandeln – im Gegenteil. Vielmehr ergibt sich daraus die Notwendigkeit einer Entscheidung, die Aufgabe, dem stetig sich wandelnden Chaos der Welt eine haltbare und dauerhafte Form abzutrotzen, mit dem Material zu bauen, das da ist, statt ständig auf das zu warten, was sein soll.

Das heißt allerdings nicht, daß man sich mit einem bloßen „Gärtnerkonservatismus“ begnügen muß. Vielmehr gilt es, aus dem Menschen das Bestmögliche herauszuholen und ihn an einer gewissen Intensität des Daseins teilhaben zu lassen, das auch immer „Agon“, also Wettstreit und Kampf ist – gegen die Unordnung, die Formlosigkeit, die Erschlaffung, den Verfall, den Tod, aber auch den konkreten Feind, den es immer geben wird.

Dem „Feind“ wird aber auch eine bestimmter Standort und ein prinzipielles Existenzrecht zugebilligt- er ist kein absoluter Feind, zu dem ihn bestimmte ideologische Zuspitzungen machen, insbesondere jene mit egalitärer Stoßrichtung. In der Notiz 9 vom 24. Juni 1994 untersucht Mohler den Begriff der „Mentalität“ . Dabei hat es ihm besonders eine Formulierung aus dem alten Brockhaus aus der Zeit vor dem Einbruch des „68er-Geistes“ angetan. „Mentalität“ bezeichnet

die geistig-seelische Disposition, die durch die Einwirkung von Lebenserfahrungen und Milieueindrücken entsteht, denen die Mitglieder einer sozialen Schicht unterworfen sind.

Das bedeutet nicht nur, daß der Mensch (hier folgt Mohler seinem großen Lehrmeister Arnold Gehlen) „anpassungsfähig“ ist, ein Wesen, das ebenso geformt wird, wie es selbst formend eingreift, „das sich selbst konstruiert, was er zum Überleben braucht“. Das heißt auch, daß jeder Mensch seinen soziologischen Ort, seine eigene Geschichte, seine eigenen guten oder schlechten Gründe und Beweggründe hat. Von hier aus wird auch eine rein moralistische Betrachtung und Verurteilung, eines einzelnen Menschen wie eines ganzen Volkes, unmöglich.

Mohlers Ansatz war verblüffend, besonders für solche Leser, die ein allzu vorgefaßtes Bild vom „Rechten“ mit sich herumtrugen. Dieser ist ja in der freien Wildbahn des Mainstreams eine geradezu geächtete Figur, im Gegensatz zu seinem umhätschelten Pendant, dem Linken, der „für seine guten Absichten belohnt wird“, und der auch dafür sorgt, daß vom Rechten möglichst nur Zerrbilder kursieren. „Rechts“ ist, wen er als solchen definiert, und wie er ihn definiert.

Es geht an dieser Stelle natürlich um den Rechten als Typus. Was die personifizierten Vertreter beider Lager angeht, so gibt es leider genug abschreckende Beispiele. Doderer sah sie als „Herabgekommenheiten“ – nicht etwa der nicht minder verabscheuungswürdigen „Mitte“ – sondern

jener Ebene, darauf der historisch agierende Mensch steht, der immer konservativ und revolutionär in einem ist, und diese Korrelativa als isolierte Möglichkeiten nicht kennt.

Mit einem Schlagwort: „konservative Revolution“. Das war für Mohler nicht nur das Etikett für ein bestimmtes, zeitlich eingegrenztes politisches Phänomen, sondern eine ganz grundsätzliche Idee, die er gerne vieldeutig schillern ließ. Seine Begriffe haben oft etwas bewußt Unscharfes, „Stimmungen“ Evozierendes, Wandelbares – sie müssen der jeweiligen konkreten Situation angepaßt werden.

Ich bin nun selber ein Initiat jener verschworenen Bruderschaft, die durch Mohler ihre entscheidenden politischen Impulse und Erweckungserlebnisse erfahren hat. Mit 25 Jahren verschlang ich in einer Nacht die Essaysammlung „Liberalenbeschimpfung“. Als ich das Buch zuklappte, war mir klar: wenn das nun „rechts“ ist, dann ist es nicht nur völlig legitim „rechts“ zu sein, dann bin ich es auch. Mir war bislang nur vorenthalten worden, daß es ein solches „Rechtssein“ auch gab – und das hatte mit einer Art zu denken ebenso wie mit einer Art zu schreiben und zu sprechen zu tun. Letztlich würde es aber vor allem, das betonte Mohler immer wieder, auch auf eine „Haltung“ und eine Art zu handeln ankommen, wobei er zugab, daß die Schreiber auch selten gleichzeitig „Täter“ sind.

Und hier fand ich nun die Quelle der „Freude“, von der ich oben sprach. Man erkennt, daß die Sprache eine Waffe ebenso wie ein Gefängnis sein kann, und daß ihre Grenzen schier unendlich erweiterbar sind. Dadurch stürzen die Begriffsgötzen und die falschen Autoritäten und die Laufgitter reihenweise ein und der Weg ins Freie wird sichtbar.

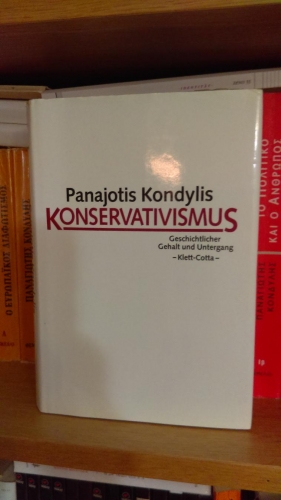

Fortan tat sich mir eine völlig neue und aufregende Welt auf. Zunächst war das nur eine Sache zwischen mir und meinem Bücherschrank. Ich suchte jahrelang keinerlei persönlichen Kontakt zu rechten oder konservativen „Milieus“, zum Teil aus Desinteresse, zum Teil aus weiterhin bestehenden Vorurteilen. Stattdessen ackerte ich sämtliche Hefte des „Criticón“ in der Berliner Staatsbibliothek durch, dem bedeutendsten Organ des konservativen Binnenpluralismus der 70er und 80er Jahre, und stieß dort auf die Namen all der konservativen Fabeltiere: neben Mohler auch Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing, Hans-Dietrich Sander, Günter Rohrmoser, Hellmut Diwald, Hans-Joachim Arndt, Günter Zehm, Wolfgang Venohr, Salcia Landmann, Robert Hepp, Gerd-Klaus Kaltenbrunner, Bernard Willms, Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Günter Maschke oder Alain de Benoist.

Fortan tat sich mir eine völlig neue und aufregende Welt auf. Zunächst war das nur eine Sache zwischen mir und meinem Bücherschrank. Ich suchte jahrelang keinerlei persönlichen Kontakt zu rechten oder konservativen „Milieus“, zum Teil aus Desinteresse, zum Teil aus weiterhin bestehenden Vorurteilen. Stattdessen ackerte ich sämtliche Hefte des „Criticón“ in der Berliner Staatsbibliothek durch, dem bedeutendsten Organ des konservativen Binnenpluralismus der 70er und 80er Jahre, und stieß dort auf die Namen all der konservativen Fabeltiere: neben Mohler auch Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing, Hans-Dietrich Sander, Günter Rohrmoser, Hellmut Diwald, Hans-Joachim Arndt, Günter Zehm, Wolfgang Venohr, Salcia Landmann, Robert Hepp, Gerd-Klaus Kaltenbrunner, Bernard Willms, Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Günter Maschke oder Alain de Benoist.

Und auf die großen Vordenker – Jünger, Blüher und Spengler waren mir schon bekannt, nun aber lernte ich Namen wie Carl Schmitt, Ernst Niekisch, Julius Evola, Edgar Julius Jung, Georges Sorel, Arnold Gehlen oder auch Donoso Cortés, Edmund Burke, Vilfredo Pareto usw. kennen. Ganz zu schweigen von all den schillernden Figuren, den Dichtern und Träumern, darunter eine erkleckliche Anzahl von poètes maudits, die ein verlockender Hauch des Hades umgab: Drieu La Rochelle, Yukio Mishima, Ezra Pound, Gabriele d‘Annunzio, Emile Cioran, Lucien Rebatet, Curzio Malaparte, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Friedrich Hielscher, Alfred Schmid… man konnte wahrlich nicht klagen, daß es drüben am „rechten Ufer“ langweilig war.

Natürlich half auch das Internet enorm weiter, und früher oder später landete jeder mit einschlägigen Interessen bei der Jungen Freiheit, deren Netzarchive ich geradezu plünderte. Bald war ich begeisterter Abonnent, und entdeckte „neue“, aktuelle Stars: Thorsten Hinz, Baal Müller (was für ein Name!), Manuel Ochsenreiter, Claus-Michael Wolfschlag, Angelika Willig. Viele Ausgaben der JF von 2002/3 habe ich heute noch aufgehoben und bewahre sie geradezu liebevoll und nostalgisch auf.

Bei der JF allein blieb es freilich nicht. Um den schwarzen Kontinent zu erobern, las ich zu diesem Zeitpunkt wie ein Scheunendrescher alles, wirklich „alles, was recht(s) ist“, frei nach einem Buchtitel von Karlheinz Weißmann, heute ein selbsterklärtes „lebendes Fossil der Neuen Rechten“, [4] der ebenfalls rasch in mein stetig wachsendes Pantheon aufgenommen wurde.

Besonders fielen mir jene Artikel in der JF und bald auch schon der Sezession auf, die von den Namen Ellen Kositza und Götz Kubitschek gezeichnet waren. Beide waren nur um wenige Jahre älter als ich, hatten markante Gesichter (dergleichen ist für mich bis heute von Bedeutung) und ihre Beiträge erklangen in einem frischen und zupackenden Ton – unverkennbar die Mohler’sche Schule. Vor allem wurde darin nicht fade herumgeschwätzt, es ging darin um etwas: um unser jetziges, wirkliches Leben, um unsere Gegenwart und Zukunft, und ich erkannte, daß all dies auch etwas mit mir und meinem Leben zu tun hatte.

Gewiß war das Netz auch damals schon voll von Antifaseiten, die mal mehr, mal weniger offensichtlich ideologisch zugespitzt auftraten. Zentraler Anlaufpunkt war eine Seite namens „IDGR“- „Informationsdienst gegen Rechtsextremismus“, die freilich auch ganz hilfreich war, wenn man neue „Lesetips“ suchte. Was mich damals besonders empörte, war die Diskrepanz zwischen der hetzerisch-dummen, schablonenartigen, immer-gleichen Sprache dieser Seiten und dem, was die denunzierten Autoren tatsächlich geschrieben und gemeint hatten. Ich konnte nur krasse Desinformation, Verleumdung und Verzerrung erkennen, und das bestärkte mich umso mehr in dem Gefühl, auf der richtigen Spur zu sein.

Das fiel besonders bei Mohler auf. Es gab einerseits den Antifa-Popanz, andererseits den Autor, der mir freier, „liberaler“ und, ja, „toleranter“ und menschlicher erschien, als irgendeine rote Schranze, die ihre Säuberungswütigkeit mit hochtrabenden Ansprüchen schmückte. Besonders nahm mich seine Kunstsinnigkeit ein. Nicht nur vermochte er es, handfest und subtil zugleich über Belletristik, Lyrik und Malerei zu schreiben – er hatte auf jedes Thema, das er behandelte, einen unverwechselbaren Zugriff.

Und es gab ein Gebiet, wo Mohler eine besonders befreiende Wirkung ausübte: nämlich in seinen Betrachtungen zum Komplex der „Vergangenheitsbewältigung“ (ein Begriff, der heute kaum mehr benutzt wird, was der Praxis, die er bezeichnete, allerdings keinerlei Abbruch tut.) Diese Bücher, insbesondere „Der Nasenring“, haben endgültig mein Klischee von einem „Rechten“ zerstört. Ihre Argumentation erschien mir gescheit, realistisch, vernünftig, erwachsen, im besten Sinne humanistisch, auch wenn ich nicht immer d‘accord war.

Ich glaube, daß jeder denkende und fühlende Mensch, der in Deutschland oder Österreich geboren ist, irgendwann einmal mit der Geschichte seines Landes und den daraus folgenden Belastungen ins Klare kommen muß. Es ist wohl kein Zufall, daß Mohler gerade dieses Schlachtfeld wiederholt aufgesucht hat, denn keines ist dichter von „All-Gemeinheiten“, ahistorischen Abstraktionen, falschen Moralisierungen, „schrecklichen Vereinfachungen“, pauschalen Urteilen und so weiter umzäunt als dieses. Wohlfeile und wohlkalkulierte oder zur Gewohnheit eingerastete Instrumentalisierungen gehen hier mit deutschen Identitätsstörungen und unverarbeiteten Traumata einher, der nationale Selbsthaß mit dem „Klageverbot“ (so Hans-Jürgen Syberberg), die politische Erpressung mit der Unfähigkeit, zu trauern.

Mohlers Ausweg aus diesem Dschungel war genial. Er leitete sich aus seiner lebenslangen Begeisterung für die schöne Literatur [5]ab, die ihm als ein unentbehrlicher Weg zur „Welterfassung“ erschien. Er lautete: dort wo, die Zangenbacken der ideologischen Abstraktionen und der moralistischen All-Gemeinheiten zubeißen wollen, dort soll man eine Geschichte erzählen.

Etwa die eines einzigen Menschen, der die Zeit des Dritten Reichs und des Zweitens Weltkriegs erlebt hat. Von Anfang an und nach der Reihe. Und dann die eines anderen, der genau das Gegenteil erlebt, und genau gegenteilig gedacht und gehandelt hat. Und dann eine dritte und eine vierte. Allmählich können wir auch wieder von Moral sprechen und von „Tätern und Opfern“, aber auf einer völlig veränderten Ebene. Diese Geschichten können Lebensberichte und Memoiren ebenso wie durchgestaltete Romane und Erzählungen sein.

Wer all dies wirklich in sich aufgenommen hat, wird zunehmends davor zurückscheuen, den Stab über vorangegangene Generationen zu brechen. Gerade die Deutschen müssen aufhören, über ihre Mütter und Väter, ihre Großmütter und Großväter, zu urteilen – sie sollten stattdessen versuchen, sie verstehen zu lernen. Wir müssen unsere ganze Geschichte annehmen, und wir brauchen uns dazu auch nicht die schlechten Dinge schönzureden.

Schließlich aber, und hier war Mohler sehr scharf, kann ein richtiges Verhältnis zur eigenen Vergangenheit nicht gewonnen werden, wenn die historische Forschung zu stark politisiert wird, wenn Fragestellungen tabuisiert werden, wenn Historiker die Ächtung fürchten müssen (und es traf auch einen Diwald, einen Nolte, nicht nur einen Irving, der indes noch in den frühen Achtzigern mit Vorabdrucken im Spiegel rechnen konnte) und wenn per Gesetz entschieden wird, was historische Wahrheit ist und was nicht. Jeder Wissenschaftler, der hier noch seine Siebensachen beisammen hat [6], wird zugeben müssen, daß eine solche Praxis äußerst problematisch ist, und daß nicht damit geholfen ist, wenn man auf die Exzesse des lunatic fringe verweist.

Nun könnte man natürlich, etwa mit Egon Friedell, sagen, daß es eine rein „objektive“ und „interessenlose“ Geschichtsschreibung nicht gibt und nicht geben kann, daß man Historiographie, die wie die Künste einer Muse unterstellt ist, nicht so betreibt wie Naturwissenschaft – aber gerade dieser Gedanke ist in alle Richtungen hin gültig. Eine Buchveröffentlichung wie Stefan Scheils jüngster Kaplakenband „Polen 1939″ [7] steht von vornherein in einem politischen Raum, da die Vorgeschichte des Weltkriegs im Staatshaushalt der Bundesrepublik kein neutrales, sondern vielmehr ein mit politischer Bedeutung hoch aufgeladenes Feld ist. Dies gilt völlig unabhängig davon, ob sich Scheils Thesen als richtig oder falsch erweisen – sie bleiben so oder so ein Politikum.

Das nun also ist auch das eigentliche Thema von Mohlers Notiz 11 (5. August 1994), die sich in vermintes Gelände vorwagte, und darum von JF-Chefredakteur Dieter Stein von einer redaktionellen Infragestellung und einer Replik von Salcia Landmann [8] eingerahmt wurde. Man kann das alles im Kaplaken-Band nachlesen, darum will ich es an dieser Stelle nicht breittreten. Landmanns Antwort fiel, bei allem Respekt, zum Teil unterirdisch undifferenziert aus und schoß meilenweit und halbmanisch am eigentlichen Thema vorbei. Mohler kannte die sehr alte und sehr eigenwillige Dame noch aus Criticón-Tagen und nahm ihr selbst den Angriff nicht übel.

Anders erging es ihm allerdings mit dem Verhalten Dieter Steins. Dieser hatte im Grunde die „Notiz“ mit großen, roten Distanzierungsrufzeichen versehen, die vielleicht ein Spur zu dick aufgetragen waren. In seinem redaktionellen Beiwort wurde Mohler als eine Art seitenverkehrter, ebenfalls auf die Täter fixierter Habermas hingestellt, der lediglich die Deutschen exkulpieren wolle, wo der andere sie in pauschale Geiselhaft nahm.

Tatsächlich hatte Mohler in seiner „Notiz“aber genau vor diesem Ping-Pong des einseitigen Anschuldigens als auch einseitigen Exkulpierens gewarnt. Freillich hatte Stein das Recht, seine eigene Position zu markieren. Es ging hier aber vor allem um das „Wie“ des Vorgangs. Mohler fühlte sich verraten und in ungerechter Weise bloßgestellt, und schrieb an den noch sehr jungen Chefredakteur:

Was ist das für ein Kapitän, der einen aus der Mannschaft dem Feind zum Fraß vorwirft?

In der aktuellen JF [9] findet sich ein wie immer ausgezeichneter Leitartikel von Thorsten Hinz über die „Macht des Wortes“. Darin zeigt Hinz an konkreten Beispielen, was Gómez Dávila mit zwei Sätzen auf den Punkt gebracht hat.

Wer das Vokabular des Feindes akzeptiert, ergibt sich ohne sein Wissen. Bevor die Urteile in den Sätzen explizit werden, sind sie implizit in den Wörtern.

Auf der Titelseite ist ein mir nicht bekannter Schauspieler namens Hannes Jaenicke zu sehen, der ein Buch mit dem Titel „Die große Volksverarsche“ geschrieben hat, in dem er „mit deutschen Journalisten abrechnet“, Zitat in der Schlagzeile: „Eure Blätter lese ich nicht mehr.“

Im Kulturteil ist skurrilerweiser versehentlich ein Old-School-Antifa-Bericht über den zwischentag [10] abgedruckt worden, der eigentlich in der taz erscheinen sollte. Der Autor, vermutlich ein Praktikant, legt darin den „Rechten“ die Freuden der sozialistischen Selbstkritik ans Herz. Er meint es gewiß nur gut, fragt sich bloß, mit wem. Vielleicht weiß auch die rechte Hand nicht mehr was die linke tut, oder irgendjemand ist mal wieder so listig wie die Tauben und so sanft wie die Schlangen, zu welchem Zweck auch immer.

Mein Artikel sollte aber von ganz anderen Freuden handeln. Aus diesem Grund will ich mit dem diesjährigen Neujahrsgeleitwort von Michael Klonovsky enden:

Lang leben die Völker dieser Erde! Es leben ihre Religionen, ihre Sitten, ihre Sprachen! Es lebe die traditionelle Familie! Es lebe die Ehe! Es leben die Geschlechterrollen! Es lebe die Weiblichkeit und die Männlichkeit! Vive la Mademoiselle! Es lebe die Monarchie! Es leben die Rassen und ihre fundamentalen Unterschiede! Es leben die Klassenschranken! Es lebe die soziale Ungerechtigkeit! Es lebe der Luxus! Es lebe die Eleganz! Es leben die Kathedralen, Kirchen und Tempel! Es lebe das Papsttum! Es lebe die Orthodoxie! Es leben die Atomkraft und die bemannte Raumfahrt! Es lebe der private Waffenbesitz! Es lebe der Aberglaube, der Geschichtsrevisionismus und der Biologismus! Es leben die Vorurteile und die Gemeinplätze! Es leben die Mythen! Es lebe alles Ehrwürdig-Althergebrachte! Es lebe die Meisterschaft in Kunst und Handwerk! Es lebe die Gewohnheit und die Regel! Es lebe der Alkohol, das Rauchen und das Fett im Essen! Es lebe die Aristokratie! Es lebe die Meritokratie! Es lebe die Kallokratie! Es lebe das Versmaß, die Hochkultur und die Distinktion! Es lebe die Bosheit! Es lebe die Ungleichheit!

Ich sage dazu, auch mitten im Jahr, Ja und Amen, und Prost, Cheers, Sláinte, Skøl und Masel tov!

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg Vor mir liegt ein frisch gedrucktes Büchlein, das mich wieder daran erinnert, was für eine große geistige Freude das „Rechtssein“ machen kann. Fast hätte ich es schon vergessen. Aber irgendeinen guten Grund muß ein Mensch ja haben, warum er sich all den Ärger antut, der damit einhergeht, nicht im linken Schafswolfsrudel mitzuheulen bzw. zu -blöken.

Vor mir liegt ein frisch gedrucktes Büchlein, das mich wieder daran erinnert, was für eine große geistige Freude das „Rechtssein“ machen kann. Fast hätte ich es schon vergessen. Aber irgendeinen guten Grund muß ein Mensch ja haben, warum er sich all den Ärger antut, der damit einhergeht, nicht im linken Schafswolfsrudel mitzuheulen bzw. zu -blöken. Fortan tat sich mir eine völlig neue und aufregende Welt auf. Zunächst war das nur eine Sache zwischen mir und meinem Bücherschrank. Ich suchte jahrelang keinerlei persönlichen Kontakt zu rechten oder konservativen „Milieus“, zum Teil aus Desinteresse, zum Teil aus weiterhin bestehenden Vorurteilen. Stattdessen ackerte ich sämtliche Hefte des „Criticón“ in der Berliner Staatsbibliothek durch, dem bedeutendsten Organ des konservativen Binnenpluralismus der 70er und 80er Jahre, und stieß dort auf die Namen all der konservativen Fabeltiere: neben Mohler auch Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing, Hans-Dietrich Sander, Günter Rohrmoser, Hellmut Diwald, Hans-Joachim Arndt, Günter Zehm, Wolfgang Venohr, Salcia Landmann, Robert Hepp, Gerd-Klaus Kaltenbrunner, Bernard Willms, Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Günter Maschke oder Alain de Benoist.

Fortan tat sich mir eine völlig neue und aufregende Welt auf. Zunächst war das nur eine Sache zwischen mir und meinem Bücherschrank. Ich suchte jahrelang keinerlei persönlichen Kontakt zu rechten oder konservativen „Milieus“, zum Teil aus Desinteresse, zum Teil aus weiterhin bestehenden Vorurteilen. Stattdessen ackerte ich sämtliche Hefte des „Criticón“ in der Berliner Staatsbibliothek durch, dem bedeutendsten Organ des konservativen Binnenpluralismus der 70er und 80er Jahre, und stieß dort auf die Namen all der konservativen Fabeltiere: neben Mohler auch Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing, Hans-Dietrich Sander, Günter Rohrmoser, Hellmut Diwald, Hans-Joachim Arndt, Günter Zehm, Wolfgang Venohr, Salcia Landmann, Robert Hepp, Gerd-Klaus Kaltenbrunner, Bernard Willms, Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Günter Maschke oder Alain de Benoist.