Alexey Khomyakov: le choix de la lumière

Alexander Douguine

Source: https://www.geopolitika.ru/article/aleksey-homyakov-vybor-sveta?fbclid=IwZXh0bgNhZW0CMTAAAR1R0W1UkcKpWk0QBsrLrLU4UMDJ8SD-ZoUEimPDG3Pb2Y5Adgg0C51yeH4_aem_AeGHvfsJribDsIlURfNfHdFQJtc4uIHoVpIl-pnBfVDA8YcSXADq3kYCXuxNra9Yj8JKnjhB2lJIu5q2lx6moctO

La « tâche » formulée par Odoevsky et Venevitinov, et plus largement par le cercle des nemultis russes, de créer une philosophie véritablement russe est devenue une tâche qui s'est étendue sur deux siècles. Les premiers à réagir furent les slavophiles, également issus de ce cercle. Plus tard, les eurasianistes ont développé leurs activités dans la même veine, et après une autre étape - les néo-eurasianistes de la fin du 20ème siècle, et enfin, cette « commande » a été prise comme un impératif dans « Noomakhia » et nos autres travaux axés sur l'exploration de la possibilité d'une philosophie authentiquement russe [1].

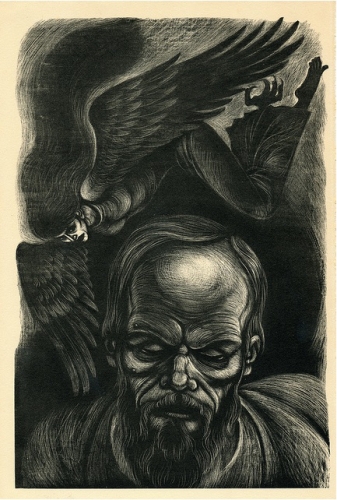

Alexei Stepanovich Khomyakov, ami proche de Vladimir Odoevsky (photo, en haut) et de Venevitinov (photo, en bas), a consacré toute sa vie à une étude comparative à grande échelle des cultures et des civilisations. Cette œuvre - « Sémiramis »[2] - n'a jamais été publiée de son vivant. Ce faisant, Khomyakov cherchait non seulement à donner une volumineuse description de chacune d'entre elles, ce qui semble évidemment impossible, mais à proposer une classification selon laquelle ces civilisations pourraient être logiquement réparties. En fait, il aborde une méthodologie sur base de Logos dominants, qui est, de fait, la base de ma « Noomachia », mais il décrit ces Logos dans d'autres termes et dans d'autres correspondances structurelles.

Khomyakov part de l'idée, courante à son époque, qu'il existe cinq races humaines - blanche, jaune, noire, rouge et "olive", correspondant plus ou moins aux cinq continents. Le pôle des blancs est l'Europe, celui des jaunes l'Asie, celui des noirs l'Afrique, celui des rouges l'Amérique, celui des aborigènes de l'Australie et du reste de l'Océanie. Peu à peu, Khomyakov arrive à la conclusion que les trois races fondamentales ne sont que trois - la blanche, la jaune et la noire - et que les deux autres - la rouge et l'"olive" - sont le produit de leur mélange. Cette division en trois races était également conforme aux vues des anthropologues d'Europe occidentale du 19ème siècle, notamment Lewis Morgan [3] (1818 - 1881), les races correspondant généralement, dans ces théories, à trois types de sociétés: la civilisation blanche, la barbarie jaune et la sauvagerie noire.

Cependant, Khomyakov ne se contente pas d'une telle systématisation et, en accordant une attention particulière à l'histoire des Slaves, qui occupent les terres non seulement de l'Europe mais aussi de l'Asie, il souligne la proximité ethnique et linguistique des peuples iraniens et indiens avec la communauté indo-européenne (indo-germanique). Il s'éloigne ainsi d'une approche raciale au profit d'une approche ethnoculturelle et linguistique. Cela l'amène à identifier les similitudes des langues et de la culture slaves avec les peuples indo-européens d'Asie - et en premier lieu avec la civilisation indienne. Ce n'est pas un hasard si, dans la première partie de Semiramis, il donne une longue liste de mots homonymes en russe et en sanskrit. Certaines convergences étymologiques ont été contestées par la suite, mais la principale conclusion de Khomyakov était tout à fait correcte : les peuples indo-européens d'Asie (Iraniens, Hindous, Afghans, etc.) et d'Europe (Grecs, Latins, Celtes, Germains, etc.) avaient une origine commune et avaient autrefois une langue et une culture communes, et les Slaves faisaient partie intégrante de cette communauté indo-européenne [4].

Khomyakov passe ensuite à l'étape suivante : après avoir reconnu que la division raciale n'est pas la plus importante du point de vue du sens de l'histoire, il propose un nouveau critère qui mérite plus d'attention. Ce n'est pas tant la race qui importe, mais le type de conception religieuse. C'est elle qui est déterminante. La façon dont Khomyakov interprète le type de conception religieuse est tout à fait conforme à l'idée de Logos dans « Noomakhia ». Dans ce cas, Khomyakov distingue deux origines fondamentales (racines) et, dans une certaine mesure, universelles : l'iranienne et la kouchite. Nous pourrions les appeler le « Logos kouchite » et le « Logos iranien ». Chacun d'entre eux est traité dans les volumes respectifs de Noomakhia [5]. Khomyakov déclare :

La comparaison entre la foi et l'illumination, qui dépend uniquement de la foi et consiste en elle (comme tout ce qui est appliqué consiste en la science pure), nous conduit à deux principes fondamentaux : l'iranien, c'est-à-dire le culte spirituel d'un esprit créateur libre ou un monothéisme primitif élevé, et le kouchite, la reconnaissance de la nécessité organique éternelle, produisant en vertu de lois logiques inévitables. Le kouchitisme se divise en deux parties : le shivaïsme, culte de la substance régnante, et le bouddhisme, culte de l'esprit servile qui ne trouve sa liberté que dans l'autodestruction. Ces deux origines, iranienne et kouchite, dans leurs chocs et mélanges incessants, ont produit cette infinie variété de religions qui a marqué le genre humain avant le christianisme, et surtout l'humanité artistique et fabuleuse (anthropomorphisme). Mais, en dépit de tout mélange, la base fondamentale de la foi est exprimée par le caractère général de l'illumination, c'est-à-dire l'éducation verbale, l'écriture des voyelles, l'utilisation de la langue française, l'utilisation de la langue anglaise, la simplicité de la vie communautaire, la prière spirituelle et le mépris du corps, exprimé par le fait de brûler ou de donner le cadavre à manger aux animaux dans l'iranisme, et l'éducation artistique, l'écriture symbolique, la structure conventionnelle de l'État, la prière incantatoire et le respect du corps, exprimé par l'embaumement, ou le fait de manger les morts, ou d'autres rituels similaires, dans le kouchitisme [6].

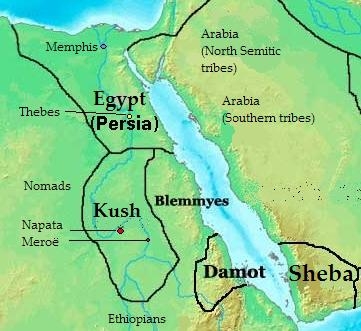

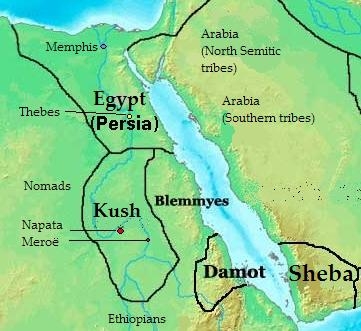

En fait, Khomyakov distingue ici le Logos d'Apollon, qui est le plus proche du Logos iranien, et le Logos de Cybèle, qu'il rapproche de la civilisation égyptienne méridionale de Kush. Ces deux métaphores sont confirmées par la Noomachie. Le Logos iranien représente l'une des formes (dualistes) les plus vivantes et les plus originales du Logos vertical-patriarcal indo-européen d'Apollon [7], tandis que l'horizon kouchite et le territoire adjacent à la Corne de l'Afrique, qui était probablement le foyer ancestral de l'ensemble du cercle culturel afro-asiatique (y compris les Sémites, les Kouchites, les Égyptiens et les Berbères), est en effet proche dans ses racines les plus profondes du Logos de Cybèle [8]. Dans le même temps, il convient de souligner la perspicacité de Khomyakov lorsqu'il distingue les Iraniens (et non les Grecs, les Hindous, les Allemands, les Latins et les Celtes) des peuples indo-européens en tant que porteurs de la culture paradigmatique. Nous arrivons à la conclusion de l'influence colossale et parfois décisive des débuts iraniens sur le judaïsme et l'hellénisme post-babyloniens (et par conséquent sur le christianisme, le byzantisme et l'Europe dans son ensemble), d'une part, et sur les vastes étendues de l'Asie - de l'Asie centrale à l'Inde du Nord, au Tibet et à la Mongolie, d'autre part, et de la profonde sous-estimation de cette influence dans notre étude sur le Logos iranien [9]. Pour Khomyakov, l'Iran est un symbole de la verticale solaire indo-européenne.

Le début kouchite est pour Khomyakov une civilisation de la fatalité, de la nécessité objective, une sorte de matérialisme sacral qui place l'homme à la périphérie de l'ontologie. C'est un trait distinctif de la civilisation de la Grande Mère, un signe clair du Logos de Cybèle. Une fois encore, la conjecture de Khomyakov sur le lien entre cette vision du monde matriarcale et matérialiste à l'origine et Kush s'avère correcte, ce qui est confirmé par nos études sur les civilisations et les cultures des peuples d'Afrique du Nord [10].

D'autre part, nous pouvons reconnaître dans cette reconstruction l'influence du regretté Schelling (tableau, ci-dessus) qui, dans ses conférences sur la « Philosophie de la mythologie » [11], a esquissé une image grandiose de l'histoire du monde comme déploiement de la pensée divine, résolvant le problème métaphysique de la signification absolue - comment le léger et raisonnable A2 initial (dans la terminologie de Schelling) formalisera sa relation avec ce qui le précède logiquement et ontologiquement - le sombre abîme apophatique - B. Nous nous sommes référés à plusieurs reprises à ce modèle de Schelling, en découvrant et parfois en corrigeant ses incohérences lorsqu'il s'agit de le mettre en relation avec certaines civilisations (par exemple, en ce qui concerne son interprétation de la culture babylonienne ou du judaïsme primitif [12]), ainsi qu'en suggérant un développement particulier de ses idées en relation avec les figures et les Gestalten (les formes) que Schelling lui-même n'a pas pris en considération (en premier lieu, la figure de Va'ala [13] ou du Trickster [14]).

Khomyakov suit également Schelling en identifiant le « début-racine » iranien avec le Logos rayonnant, A2, et la culture, où le début B, le poids ontologique de la donation autoréférentielle, prédomine complètement, avec le Logos kouchite. Si nous laissons de côté les détails historiques, ethnologiques, linguistiques et religieux, qui, chez Khomyakov, ne demandent pas moins de correction que chez Schelling, le tableau est le suivant : l'histoire du monde est le développement successif de la lutte entre le Logos iranien et le Logos kouchite, c'est-à-dire A2 et B, ou, dans les termes de ma « Noomachia », le Logos d'Apollon et le Logos de Cybèle. C'est ainsi que se construit la dialectique de l'histoire du monde, qui commence par la domination inconditionnelle du Logos iranien, qui est ensuite remplacée par le triomphe du Logos kouchite. Nous voyons ainsi avec la plus grande clarté dans Sémiramis la première version de la « Noomakhia » russe. C'est ce qu'écrit Khomyakov :

Un regard sur l'ancienne dispersion des familles et l'ancienne dispersion de la race humaine, sur la structure fine, polysémique et spirituellement vivante du langage primitif, sur l'espace infini des déserts traversés par les premiers habitants de la terre, sur l'infinité des mers traversées par les fondateurs des premières colonies océaniques, sur l'identité des religions, des rites et des symboles d'un bout à l'autre de la terre, présente une preuve incontestable de la grande illumination, La déformation ultérieure de tous les principes spirituels, la sauvagerie de l'humanité et la triste signification des âges dits héroïques, où la lutte de forces violentes et anarchiques a englouti toutes les grandes traditions de l'antiquité, toute la vie de la pensée, tous les débuts de la communication et toute l'activité intelligente des peuples. Le germe de ce mal se trouve évidemment dans ce pays auquel la gloire ouvre plusieurs âges historiques, dans le pays des Kouchites, qui, plus tôt que tous les autres, oublièrent tout ce qui était purement humain et remplacèrent cet ancien commencement par un nouveau commencement, conventionnellement logique et matériellement formé" [15].

Cette déclaration, cruciale pour comprendre l'essence de la doctrine slavophile, contient un appel direct au Logos d'Apollon, qui pour Khomyakov est la vérité inconditionnelle, le bien et le but. En se plaçant du côté de l'« Iran », Khomyakov se positionne sans ambiguïté dans l'armée des fils de la Lumière, du côté de la verticalité patriarcale et de la liberté céleste. C'est ici que les Slaves devraient être du côté d'Apollon - en tant que dernière légion du Logos de la lumière, prenant le relais des peuples européens et asiatiques qui ont perdu leur mission sous l'assaut du Logos de Cybèle (le début indigène kouchite). En même temps, les derniers mots de ce fragment ne laissent aucun doute sur la manière dont Khomyakov lui-même et les autres slavophiles (ainsi que les membres du cercle des nemüdrovs) évaluent la civilisation moderne de l'Europe occidentale d'aujourd'hui. Elle est dominée par le Logos de Cybèle, et les principes du « début logique et matériellement éduqué » sont élevés au rang de valeur suprême et d'objectif ultime. D'où l'appel à s'opposer non seulement à l'Occident, mais à l'Occident moderne, qui a fait le même choix que de nombreuses civilisations anciennes, en abandonnant le commencement iranien au profit du commencement kouchite. Le Logos solaire doit désormais être défendu par les Slaves.

Ainsi, l'appel aux civilisations anciennes et la tentative d'identifier certains schémas sémantiques dans l'histoire mondiale conduisent Khomyakov à la justification de l'identité russe et à la formulation de la mission historique des Russes et, plus largement, des Slaves. Dans ce cas, le point de référence de Khomyakov est la pensée germanique - en particulier les romantiques, les philosophes idéalistes qui ont été les premiers à s'approcher du problème du sujet radical [16] - Fichte, Schelling, Hegel. Le problème de l'Europe est que les valeurs bourgeoises libérales-démocratiques - essentiellement kouchitiques, mercantiles, matérialistes - y ont prévalu, représentées de la manière la plus frappante par l'empirisme anglais et le rationalisme français, c'est-à-dire que l'Europe est anglo-française, et non germano-slave. Ainsi, Khomyakov écrit :

La France et l'Angleterre sont malheureusement trop peu au courant du mouvement savant de l'Allemagne : elles ont pris du retard sur le grand guide de l'Europe. (...) Il reste le monde germanique, véritable centre de la pensée moderne. Celui qui a préparé tous les matériaux devrait avoir construit l'édifice.

Les œuvres de Herder, Schelling et Hegel sont les fondations d'un tel édifice de l'histoire mondiale. Plus tard, Oswald Spengler [17] (1880-1936) se fixera le même objectif, mais les Russes devraient également participer à la construction de cette version apollinienne de l'historien du monde. L'œuvre de Khomyakov elle-même est une contribution significative à ce projet ; plus tard, une image encore plus détaillée et élaborée de la multiplicité des types historico-culturels et de leurs missions spéciales sera offerte par le slavophile de la seconde génération Nikolaï Danilevsky (1822 - 1885).

Les slavophiles prirent donc la « commande » de Venevitinov très au sérieux et commencèrent à préparer le terrain pour l'émergence d'une philosophie russe distincte qui, aux yeux des slavophiles eux-mêmes, pouvait et devait être une défense radicale du Logos d'Apollon et une bataille contre le commencement kouchite - matérialiste et strictement immanent.

Cette bataille ne concernait pas seulement les relations entre la Russie et l'Occident, et plus précisément entre la modernité de l'Europe occidentale, mais plutôt le champ de confrontation entre les débuts iraniens et kouchites, c'est-à-dire le Logos d'Apollon et le Logos de Cybèle. Ce champ est devenu l'ensemble de la société russe du 19ème siècle, divisée en deux camps. Khomyakov, dans l'un de ses articles polémiques dirigés contre l'historien occidentaliste S. M. Soloviev (1820-1879), a fait la remarque suivante:

L'esprit expérimental s'est tourné plus strictement qu'auparavant vers toute notre vie et toutes nos lumières, y cherchant des courants hétérogènes et justifiant ou condamnant les phénomènes de la vie et l'expression de la pensée non seulement par rapport à eux-mêmes, mais aussi selon que l'on approuve ou rejette le courant qui s'en dégage. C'est ainsi que sont nées deux tendances auxquelles tous les hommes de lettres appartiennent plus ou moins. L'une de ces directions reconnaît ouvertement au peuple russe le devoir d'un développement original et le droit à une pensée autochtone ; l'autre, dans des expressions plus ou moins claires, défend le devoir de notre attitude d'étudiant constant à l'égard des peuples de l'Europe occidentale, et s'est récemment exprimée ex cathedra, avec une extrême naïveté, en déterminant que l'enseignement n'est ni plus ni moins que l'imitation [18].

Ces deux camps sont les slavophiles et les occidentalistes. Les premiers s'appuient sur l'identité russe, en la fondant sur les structures du Logos indo-européen apollinien, tandis que les seconds insistent pour poursuivre la « seconde traduction » et suivre passivement la logique et le rythme des Modernes de l'Europe occidentale (anglo-française), ce qui équivaut à leur défense du Logos de Cybèle et du commencement kouchite. En même temps, les slavophiles parlent de « développement original » et d'« auto-développement » dans le contexte de la justification d'un sujet russe indépendant. Il s'agit de la construction d'une histoire russe et de l'établissement d'une philosophie russe, qu'Odoevsky appelait également de ses vœux. Dans ce cas, ce n'est pas simplement que les Slavophiles appellent à penser de manière indépendante, et les Occidentaux à imiter la culture étrangère. La civilisation de l'ancienne Russie jusqu'à la fin de l'époque de la Russie moscovite était largement basée sur la traduction, mais la « grande traduction » du byzantinisme, couronnée par la théorie de Moscou comme troisième Rome et le couronnement d'Ivan IV comme tsar, était un engagement avec le Logos d'Apollon, tandis que la « seconde traduction », qui a débuté à l'époque de Pierre et est devenue la principale stratégie de l'occidentalisme russe, a entraîné la chute de la Russie dans l'abîme du matérialisme, de l'individualisme, de l'empirisme et de l'athéisme, c'est-à-dire dans l'abîme de la métaphysique kouchite de la Grande Mère.

Notes:

[1] Дугин А.Г. Мартин Хайдеггер. Возможность русской философии; Он же. Русский Логос - русский Хаос. Социология русского общества;Он же. Абсолютная Родина; Он же. Геополитика России; Он же. Археомодерн; Он же. Русская вещь в 2т. М.: Арктогея-Центр, 2001; Он же. Этносоциология. М.: Академический проект, 2012.

[2] Хомяков А.С. Семирамида.

[3] Морган Л. Г. Древнее общество или исследование линий человеческого прогресса от дикости через варварство к цивилизации. Ленинград: Институт народов Севера ЦИК СССР, 1935.

[4] Дугин А.Г. Ноомахия. Логос Турана. Индоевропейская идеология вертикали; Он же. Ноомахия. Восточная Европа. Славянский Логос: балканская Навь и сарматский стиль.

[5] Дугин А.Г. Ноомахия. Иранский Логос. Световая война и культура ожидания; Он же. Ноомахия. Хамиты. Цивилизации африканского Норда. М.: Академический проект, 2018.

[6] Хомяков А.С. Семирамида. С. 442 – 443.

[7] Дугин А.Г. Ноомахия. Иранский Логос. Световая война и культура ожидания.

[8] Дугин А.Г. Ноомахия. Хамиты. Цивилизации африканского Норда.

[9] Дугин А.Г. Ноомахия. Иранский Логос. Световая война и культура ожидания.

[10] Дугин А.Г. Ноомахия. Хамиты. Цивилизации африканского Норда.

[11] Шеллинг Ф.В. Философия мифологии. В 2-х томах.

[12] Дугин А.Г. Ноомахия. Семиты. Монотеизм Луны и гештальт Ва’ала.

[13] Дугин А.Г. Ноомахия. Семиты. Монотеизм Луны и гештальт Ва’ала.

[14] Дугин А.Г. Ноомахия. Цивилизации Нового Света. Прагматика грез и разложение горизонтов. М.: Академический проект, 2017; Он же. Ноомахия. Восточная Европа. Славянский Логос: балканская Навь и сарматский стиль; Он же. Ноомахия. Царство Земли. Структура русской идентичности.

[15] Хомяков А.С. Семирамида. С. 443.

[16] Дугин А. Г. Радикальный Субъект и его дубль. М.: Евразийское движение. 2009.

[17] Шпенглер О. Закат Западного мира. М: «Альфа-книга», 2014.

[18] Хомяков А.С. Замечания на статью г. Соловьева «Шлецер и антиисторическое направление»/ Хомяков А.С. Сочинения в 2 т. Т. 1. С. 519.

Фрагмент книги Дугин А.Г. Ноомахия. Русский Логос-III. Образы русской мысли. Солнечный царь, блик Софии и Русь Подземная.

À la plainte de Schelling (ci-contre) contre une foi occidentale trop profondément infusée de rationalisme et faisant état de sa difficulté de créer une religion « pour soi-même » qui en soit épargnée, succède son appel à la Russie comme étant « destinée à quelque chose de grand ». Cette main tendue, les slavophiles la saisissent en se présentant comme ceux qui ont trouvé la solution au problème romantique : la Russie orthodoxe.

À la plainte de Schelling (ci-contre) contre une foi occidentale trop profondément infusée de rationalisme et faisant état de sa difficulté de créer une religion « pour soi-même » qui en soit épargnée, succède son appel à la Russie comme étant « destinée à quelque chose de grand ». Cette main tendue, les slavophiles la saisissent en se présentant comme ceux qui ont trouvé la solution au problème romantique : la Russie orthodoxe.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Nikolai Berdyaev in The Russian Idea affirms what Spengler describes:

Nikolai Berdyaev in The Russian Idea affirms what Spengler describes: TARAS BULBA

TARAS BULBA

Reduce God to the attribute of nationality?…On the contrary, I elevate the nation to God…The people is the body of God. Every nation is a nation only so long as it has its own particular God, excluding all other gods on earth without any possible reconciliation, so long as it believes that by its own God it will conquer and drive all other gods off the face of the earth. …The sole ‘God bearing’ nation is the Russian nation… (Dostoyevsky, 1992, Part II: I: 7, 265-266).

Reduce God to the attribute of nationality?…On the contrary, I elevate the nation to God…The people is the body of God. Every nation is a nation only so long as it has its own particular God, excluding all other gods on earth without any possible reconciliation, so long as it believes that by its own God it will conquer and drive all other gods off the face of the earth. …The sole ‘God bearing’ nation is the Russian nation… (Dostoyevsky, 1992, Part II: I: 7, 265-266).