Editor’s Note:

One of the aims of the North American New Right is to promote a revival of the Right-wing artistic and literary subculture that gave us such 20th-century giants as D. H. Lawrence, Gabriele D’Annunzio, F. T. Marinetti, Knut Hamsun, W. B. Yeats, Ezra Pound, Wyndham Lewis, Henry Williamson, Roy Campbell, and H. P. Lovecraft (all profiled in Kerry Bolton’s Artists of the Right [2]).

A group that showed some promise in this direction was the Angry Young Men of the 1950s, although the movement fizzled. Or perhaps it just came too soon. With that possibility in mind, I am reprinting Bill Hopkins’ 1957 Angry Young Men manifesto “Ways Without a Precedent” as an aid to reflection on the role of the artist in the current interregnum. For more on Hopkins and the Angry Young Men, see our articles by Jonathan Bowden [3] and Margot Metroland (part 1 [4], part 2 [5]) and our tags for Bill Hopkins [6] and Colin Wilson [7].

The literature of the past ten years has been conspicuous for its total lack of direction, purpose and power. It has opened no new roads of imagination, created no monumental characters, and contributed nothing whatever to the vitality of the written word. The fact that the decade in question has shown the highest ratio of adult literacy in British history makes this inertia an astounding feat. So astounding, indeed, that the great majority of readers have turned their attention to the cinema, television and radio instead. Their reading talent has been commandeered by the more robust newspapers.

The truants can hardly be blamed for seeking livelier entertainment, since most writers have reduced themselves to the rank of ordinary entertainers, and for the most part, have failed to be even this. Writers see the shadow of the mass mortuary too clearly to provide good, knock-about entertainment. The same shadow prevents them from producing more enduring work by making nonsense of posterity.

All writers must accept this shadow across their consciousness as an occupational hazard, and its surmounting divides them cleanly into the camps of optimism or pessimism, allowing no shades of neutrality between. The negative acceptance has the strongest following just now, and for this reason the bulk of serious novels today almost inevitably offer victims as their cast and senseless brutality as their business. These works do not educate us a scrap, nor do they offer any great insights into the tumult of our time. The writers dwell instead on the horror of anything changing—man, mood or scene—and reveal that the precise value of all and everything is that it is here at present. The understanding is that Man is too frail and imperfect for violent change. It is a poor argument for literature, progress and health.

Unless there is a radical change in this outlook literature will continue its drift into negativism.

Many people have their own ideas of what a creative writer’s job should be. The popular conception is that he should provide stories that are an escape from life. The slightest whiff of reality is regarded as an intrusion of the diabolical and an act of treachery. The ideal path amounts to improbable love yarns closing upon chaste kisses. If there is invariably an impoverished odour about these fabrications, the accolades of best-seller returns do not hint at it.

This view is not taken by the more intelligent, who demand a measure of truth with their entertainment. This again is asking for too little. The measure of truth dealt out is generally confined to obscene language in kitchen squalor and the dreary divesting of the heroine’s virginity. Now unalloyed sex is a tedious business when it is repeated too often. But this is not borne out by the positive glut of literary prurience that has come our way over the past few years. As it shows no sign of stopping we must conclude either that the percentage of perverts is much higher than is imagined, or that there is nothing more pornographic than a half-truth. But, whichever it is, the fact remains that when it is only a small measure of truth that is requested, the result merely mirrors appearance. It never delves to the cause behind appearance. It is better to offer no truth at all than make this kind of compromise.

There are only a few who demand all the truth a writer possesses. Over the past twenty years, this demand was sufficient to encourage the development of Hermann Hesse and Thomas Mann, but few others of major creative stature. If the demand were extended to a larger and more perceptive audience it would doubtless encourage the emergence of even greater writers. Certainly it would produce a literature capable of vigorously advancing our present half-hearted ideas of living to an unprecedented level.

There is no likelihood of such an ideal audience coming into existence for the philanthropic purpose of encouraging a vigorous literature. This would be asking for a healthiness that does not exist among most intelligent people today. The same malady that prevents a vital literature from developing and becoming a regenerative force to our society, disposes of the idea of a sick audience transcending its condition and calling for chest expanders. Contemporary literature, whether on the printed page or declaimed from the boards of the theatre, shows its bankruptcy by confining itself to merely reporting on social conditions. It makes no attempt at judging them. Literature that faithfully reflects a mindless society is a mindless literature. If it is to be anything larger, it must systematically contradict the great bulk of prevalent ideas, offer saner alternatives, and take on a more speculative character than it has today. I am optimistic enough to think that immediately the results prove positive and exciting, the more conformist brands of literature will lose most of their following.

But the failure of literature is only a small part of a much wider catastrophe. When I refer to a lack of health among the intelligent, I touch upon what threatens the whole of our civilization with imminent collapse. The truth is that Man, for all his scientific virtuosity, cannot defeat his own exhaustion. To do so means drawing upon unused strengths that once would have been described as religious. Unfortunately, Man has become a rational animal; he rejects any suggestion of religiosity as scrupulously as an honest beggar denounces respectability. I say unfortunately, because it is mental and physical exhaustion that is the principal malady of our civilization. The very people who should be the leaders of our society are the most affected, so the disillusionment, despair and social revolt of our age has been allowed to grow unchecked.

All the problems and struggles that confront the growth of our civilization depend entirely on whether we can get an exhausted man back upon his feet and keep him there. If the answer is a negative one, our past counts for nothing: it has proved insufficient to preserve our future.

The reasons for this exhaustion are all documented and detailed in the archives of the past fifty years. Rationalism, Communism, Socialism, Labourism, Fascism, Nazism, Anarchism; the honest penny-ha’penny thinking that human happiness was an adequate goal, the quest for social equality; two world wars and a couple of dozen local blood-lettings; poison gas, tanks, aircraft, flame-throwers, atomic, hydrogen and cobalt bombs, bacteriological warfare; depressions, inflations, strikes . . . the documents are quite explicit and well known.

Altogether they amount to the exhaustion of a man with asthma having run a marathon race and found there were no trophies or glory at the end of it. That is exactly our own position. With every decade since the turn of the century we have intensified our endeavours while our condition has deteriorated. Now it seems that despite all our efforts, knowledge and hopes, besides the lives jettisoned in their millions, we have achieved nothing. The dry taste of futility lingers in the mouth of all. The energy of any flying spark is in itself enough to arouse popular amazement. The supineness of the intelligent is the tragic paradox of the Atomic Age. Only the insulated specialists, bafflingly capable of drawing the blinds against all other realities, remain enthusiastic about tomorrow.

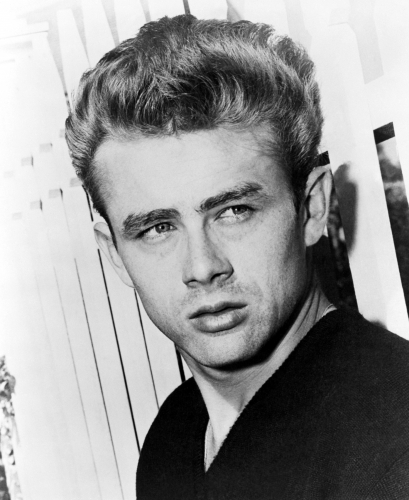

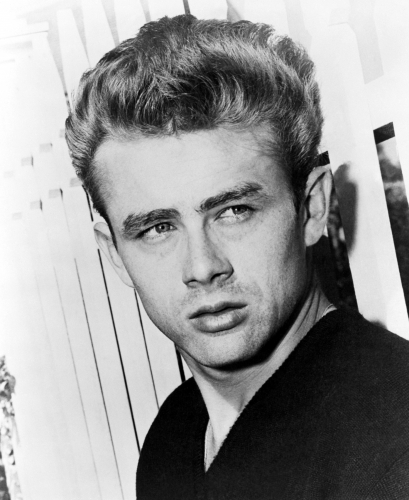

James Dean

The evidence of exhaustion stares out from the columns of the daily newspapers. The references to ‘Angry Young Men’ for ex-ample, record a general astonishment at the vigour of simply being angry. Another instance is the hero-worship of the late James Dean, who posthumously remains as the embodiment of Youth’s violent rebuttal of a society grown pointless. That the rejection is equally pointless does not appear to matter; the sincerity redeems it. There is the idolization of such simple men as Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley, the respective champions of wistful sentimentality and the stark voluptuousness of knowing one thing that’s good, anyway. Which, after all, is one advantage of being a farmer’s boy.

Significantly, the more thoughtful go only a few steps further to admire such writers as Samuel Beckett, Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller. All of these playwrights have distinguished them-selves for creating small men and women whose unlikely poetry is in their bewilderment in an inexplicable and often tyrannical world. The heroism of the Twentieth Century Man, as currently postulated, is: (a) in winning a compassionate pair of lips that will lull him to peace after an endless gauntlet of victimizations (thus mysteriously negating the lot), (b) kicking a bullying foreman (an enemy of the people) in a conclusive place, or (c) just inhabiting a dustbin with all the pretences down and stoically waiting for the end.

This is the landscape a new writer looks upon this year. Every-thing has deteriorated from the point in the mid-1940s we optimistically imagined to be already rock-bottom. What is left is a mockery of attempt, accomplishment and greatness.

It would be too easy to be angry and join the lynching parties. But this is not a writer’s job. Nor is it for a writer to subscribe to the general bankruptcy, despair and apathy around him, whatever popularity might be obtained from it. If there is a task for the writer, it is to stand up higher than anyone else and discover the escape route to progress. His function is to find a way towards greater spiritual and mental health for his civilization in particular and his species in general. This is my own intention, and unless other writers adopt the same attitude our civilization will remain leaderless, lost and exhausted, and the chaos will continue until its eclipse under radio-active clouds.

Literature has been an accelerating factor to this state of affairs over the last decade. Instead of acting as a brake it has been intent upon glorifying the lostness, the smallness and the absolute impotence of Man under adverse conditions. This is the reverse of what its role must be in the future. It must begin to emphasize in every way possible that Man need not be the victim of circumstances unless he is too old, shattered or sick to be anything else. It is the conquest of external conditions that determines the extent of Mankind’s difference from all other forms of life; and, in turn, decides the superiority of its leaders. If this is denied, then we are indeed due for elimination. Perhaps overdue. But contemporary writing will not bring itself to this assertion until it has been wrenched clear of its embrace with a falling society. The dismaying fact is, most writers seem quite satisfied to act out their present hysterical offices to the length of disaster itself. Their conversion is enough to set any salvationist with work to last several lifetimes.

It is customary for young writers to condemn those who have authority and influence. For my own part, I am unable to do this because I find their exhaustion only too understandable. The leaders of our civilization have strained at hopelessly impossible tasks for too long, and instead of creating a new structure for living, they have succeeded only in producing a succession of failures. Today they have reached a standstill, and the prospect of marshalling together one more attempt has become an outrage against all reason and experience.

They are reasonable men and their conclusion is, in the light of what they have done, entirely rational. If reason or rationalism can accept exhaustion, by the same terms ruin and death are equally acceptable. But survival is our inflexible rule of health; and since survival has become a completely irrational instinct, the time has arrived when we should look to the irrational for the means to reject this reasonable but (humanly speaking) unacceptable end of our civilization.

Firm upon this premise, I predict that within the next two or three decades we will see the end of pure rationalism as the foundation of our thinking. If we are to break out of our present encirclement, we must envisage Man from now on as super-rational; that is, possessing an inner compass of certainty beyond all logic and reason, and ultimately far more valid.

The times we are entering require a far more flexible and powerful way of thinking than rationalism ever provided. Three sovereign states have been loosing hydrogen tests in the world’s atmosphere in preparation for deterrent wars. Each new explosion shadow-boxes with genetical mutations in the coming generations. Populations everywhere are multiplying daily to that frightening point in the future when the earth’s food resources will not be sufficient to supply all with one decent meal a day. The fish harvests from the oceans are diminishing. The problems of soil erosion and the reclamation of land swallowed up by water remain unattended. These are only a few of the more obvious questions that call for solutions on a new level. A level of universal planning that can only be encompassed by a supranational body like world government. Meanwhile, science advances every year a trifle further beyond the comprehension of most of the human race.

The path of a civilization in our disorders leads directly to its extermination. And, while we take it, Proustians talk about their sensitivity in dark rooms and stylists continue to manufacture their glittering sentences. This is the marrying of an illness to a deformity; a grotesque mésalliance to make even a lunatic marvel. But it will go on, as I say, until writers turn away and look objectively to another part of the horizon.

I have stated that Man is more than rational, and that if he is not, he is finished. Now I take the argument forward another step and assert that his current exhaustion is the vacuum created by an absence of belief. At the beginning of this credo I declared that only a religious strength could conquer exhaustion, and by religious strength I meant, specifically, belief: exhaustion exists only to a degree commensurate to its wane. A complete dearth of belief mathematically equates to utter exhaustion. It is no coincidence that it has struck the most responsible members of our society; they are the ones who have had the responsibility of scraping the barrel of reason and materialism. The same exhaustion will strike at the leaders of the East just as surely within a span of time roughly corresponding, no doubt, to our own venture into pure rationalism.

Through history, the men and women who have towered over their contemporaries through their achievements and struggles have had extraordinary levels of belief. They have ranged from visionaries, saints and mystics to fanatics and plain, self-professed, men-of-destiny. Whether their beliefs were in an external thing—let us say the Church—or simply in themselves, was a matter of little importance. The result in every case was sufficiently positive to make them memorable. Each of them was primarily separated from those around him by a greater capacity for belief. It took all of them high above the eternally small, grumbling, self-pitying parts that constitute personality. Belief is, and I speak historically, the instrument for projecting oneself beyond one’s innate limitations. Reason, on the other hand, will have us acknowledge them, even when the recognition is disastrous, as now.

The admission of a permanent state of incompleteness has been made by a great many people and much of the damage I have referred to is the direct result of it. But their places have to be filled. It has become imperative that, just as a new way of thinking and a new literature are needed, a new leadership must also be evolved with the aim of combating this exhaustion by the restoration of belief.

When I speak of belief in the present context, I do not mean any belief in particular, of course, but rather belief divorced from all form whatsoever. The form is an arbitrary matter, and its choice in the sense of literature is essentially a matter for the writer’s temperament. Whatever the choice, the reservoir of power within belief offers any writer the certainty of major work.

It is obvious that this concern with belief leads inevitably to the heroic. The two are joined as essentially as flight to birds. The hero is the primary condition of all moral education, and his reality is synonymous with any great idea. He is literally the personification of the dramatic concept. But the heroic poses the possibility of people who can think and act with a magnitude close to the superhuman. The introduction of such characters and events will require a great deal of care and skill, for the ridiculous is only one step away.

The greatest difficulty overhanging this work, however, will be in the motive force itself. There has been a nonsensical confusion between belief and religion that has lasted for centuries. Instead of belief finding its separate identity, it has always been inextricably tied to religion. Churches of every denomination deliberately fostered this misconception from their beginnings, for the belief latent in men responded to hot appeal and willingly testified to the truth of any proffered set of doctrines. The nature of belief appears to be conducive to appeals. Its generosity is evident in this respect when we examine many of the childish and absurd inventions the various religions have offered worshippers at one time or another.

It is quite true that the Church has been the only vehicle for belief on any sizeable scale up to the present, and deserves credit for it, although self-interest provided its own reward. But it is absurd to regard belief on the basis of tradition as the monopoly of any organization. The Church was the first to understand the potentialities of its power and was also the first to direct it to an end; but sole proprietary rights were assumed too rigidly for the Church to pass us now as a public benefactor. Those who tried to break the monopoly were decried as heretics. Where it could, the Church had them burnt. This confiscation of belief and its isolation under the steeple brought about the Reformation and eventually the George Foxes and other champions of the right to independent belief.

Over the past fifty years there has been a general rejection of all churches with the sole exception of the strongest, Catholicism. The rejection parcelled belief with the Church and disposed of both. It was the result of a considerable amount of ignorance and a distinct lack of subtlety. Today, the same excuses do not hold, and if the mistake is repeated, it can never be done with the same blind vehemence of the first rejection.

If this social exhaustion of ours is due to the rejection of belief, how can writers reclaim it? There are three choices open, at least. The first is the establishment of a new religion. The second, to revitalize and reconstruct Christianity. The third, to trace belief to its source and turn it to a new account.

The argument against the first is that a new religion, whatever advantages it would have (supposing for a moment that it should find an ample crop of visionaries, priests, theologians and militant doctrines), would suffer from its lack of tradition more than it would profit by its modernity. Although many people talk somewhat loosely about the need for a new religion, the very impossibility of it as an overnight phenomenon rules it out for today.

However, should this particular miracle come to pass, its contribution to our civilization would be a substantial one while it was sustained by its visionaries. But as soon as the visionaries died, its hierarchy would become rigid as precedents in the history of every church show us without exception. There would be no more room for succeeding visionaries with their tradition-breaking habits in this church than in any other.

A priest is a poor substitute for a visionary. So poor, in fact, that the plenitude of them against the paucity of visionaries has largely dissuaded many who with the right inspiration would be religious. A visionary has the prerogative of freely contradicting himself while still retaining his influence. Less flexible, because he happens to lack a visionary’s imagination and vitality, the priest conscientiously commits to paper everything enunciated by the other in case he should forget the passport of his office. Subsequent generations of priests accept the dogmas laid out for them without demur or question on the same grounds. This is orthodoxy; its strength is in its ossification. The more rigid the observance, the more virtuous the believer . . .

There can be no prospect more terrible for any prophet coming after, and this is when a church really dies. When it is attacked from without, what is sent crashing is cardboard: the Church died after the passing of its first visionaries and the hardening of its arteries to fresh truths.

As this argues against the possibility of a new religion arising, it argues equally against the impossibility of a revitalized Christianity. Any great idea, if it is perpetuated without continual reappraisals, is eventually rendered into ritualistic twaddle and shibboleths that justify the cheapest sneers (although not the spirit) of its detractors. And finally, the sad truth is that the only men courageous enough to approach great ideas and test their truth are men of equal stature to their formulators. No church that I am aware of has produced an apostolic succession of this order, so we must put aside both possibilities as impractical for anyone who hopes to work within his own times.

The last alternative is the one that, under the circumstances, is the most realistic. If we can trace belief to its origins and examine it in terms of plain, unadorned power, we have a potential weapon that will play an immeasurable part in our salvaging. I am convinced that it is an internal power comparable, when fully released, to the external explosions of atomic energy. With a complete understanding of its nature, its functions and its strength at zenith, I believe that we can not only cure Man’s many illnesses, but determine by its use a level of health never before attained. If we can learn the answers to these questions, Man may be transformed within a few years from the hardening corpse he has become into a completely alive being. The change can only be for the better.

One of the most tiring assumptions that has gained universality is that Man is completely plotted, explored and known. Dancing to the cafe orchestra of Darwin and Freud, there has been a tendency over the last fifty years to regard humanity as a fully arrived and established quantity that has little variation and no mystery to the scientist. Nothing could be more untrue. Man is so embryonic that attempting to define him today is preparing a fallacy for tomorrow. He is inchoate, only just beginning. Given unlimited belief and vitality, he is capable of all the impossibilities one cares to catalogue, including the most preposterous. Equally, without belief and vitality, he is simply decaying meat like any other fatally wounded animal. The difference will be largely decided by writers.

This is not a disproportionate claim. Writers have always influenced and led the thinking of their own times, immediately after the heads of State and Church. Sometimes, as with the Voltaires, a long way in front of either of them. The present heads of State are clearly unable to see a way through the difficulties of today, and there is no reason for us to suppose they can do any better with tomorrow. The non-existence of any influential Church leaders in Britain prohibits any criticism of their recalcitrance. The only remaining candidates qualified as leaders are writers.

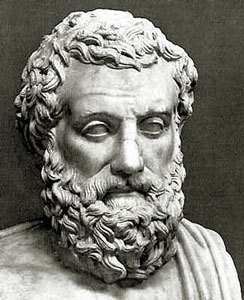

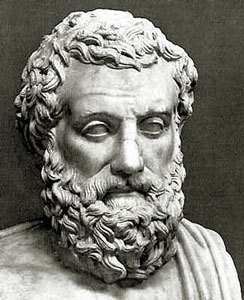

The Greeks, unlike ourselves, expected their literary men to be thinkers and teachers as a matter of course. This expectation was justified by figures of the stature of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides. Dramatists like these preached, taught, entertained and prophesied with such vitality and authority that their judgements were taken away by their audiences and applied to all levels of civic life. That both playwrights and audiences prospered upon this didactic relationship is best shown by the intellectual versatility of the Hellenic world, which has yet to be repeated.

The Greeks, unlike ourselves, expected their literary men to be thinkers and teachers as a matter of course. This expectation was justified by figures of the stature of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides. Dramatists like these preached, taught, entertained and prophesied with such vitality and authority that their judgements were taken away by their audiences and applied to all levels of civic life. That both playwrights and audiences prospered upon this didactic relationship is best shown by the intellectual versatility of the Hellenic world, which has yet to be repeated.

When Bernard Shaw demanded that the theatre should be a church, he also meant that the ideal church should be a serious theatre. So it was in the Greek world. Nobody could afford to miss a sermon of this sort, because there was nothing more intellectually and spiritually exciting to be found from Kephallenia to far Samoso. Each new drama-sermon made the Kingdom of Man a titanic affair that could not be taken casually, and if this is not a religious understanding, there is no such thing!

In addition to this laudable state of sanity, they had none of the blank one-sidedness about them that stamps the orthodox priest, because their real religion was Man, and no other. Because Man is only human when he is in movement, they were able to throw him into catastrophic dilemmas that modern religion would regard as blasphemous. But they threw him only to retrieve him, and by this method they were able to add new understandings of his darker territories and enlarge his consciousness. With the aid of such dramatists the citizens of the Greek city-states developed into creditable human beings. But the high level of the theatre was to fall, and the whole of the Greek world was not long in following it.

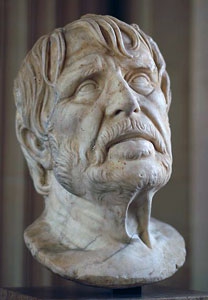

When the Roman Empire rose to take its place, Terence and Seneca, the bright lights of Latin, reflected a frightening deterioration in what was expected of a writer. Julius Caesar found it an easy matter to be both a swashbuckler and a scribe in a world that, culturally, could not even conquer sculpture. But Rome’s poverty was magnificence compared to the bankruptcy prevailing in Britain and everywhere else in the civilized world today.

When the Roman Empire rose to take its place, Terence and Seneca, the bright lights of Latin, reflected a frightening deterioration in what was expected of a writer. Julius Caesar found it an easy matter to be both a swashbuckler and a scribe in a world that, culturally, could not even conquer sculpture. But Rome’s poverty was magnificence compared to the bankruptcy prevailing in Britain and everywhere else in the civilized world today.

However, when I call in history to augment my contentions I am beating upon a broken drum. The role I predict for writers is one entirely without precedent, and it is the better because of it. Aeschylus and his colleagues refined the Greeks, and that was quite enough for their day. But today writers must become the pathfinders to a new kind of civilization. That new civilization remains an impossibility until we extricate our own civilization from the destruction that threatens it.

The problem is that of the individual. What kind of man or woman survives cataclysmic events better than any others? What kind of people are the first to fall? What are the first disciplines necessary for a new, positive way of thinking? These questions, together with ten thousand others, fall into the kind of prophetic writing that will be needed to solve the problems that lie immediately ahead. The duty then of all writers who are concerned with tomorrow is to concentrate on defining human characters at differing stages of ideal health. From this gallery it will be possible for us to aim at men and women dynamically capable of laying the foundations of our new world. We may not be able to describe precisely the men and women we want, but at least we can provide a reasonable indication. We can narrow the perimeter of choice.

I realize that there is as great a difference between facts and speculations in the minds of writers as in the minds of ordinary people. The great difference is that writers are particularly suited to the correlation of apparently hostile facts, often blatant contradictions, and their craft teaches them to deepen and extend thoughts to final understandings that seem almost mystical to the average person. This talent to reach down into the depths of men and find appalling corruption, and far from being ruined by the revelation proceed to conceive supreme peaks of human perfection, is common to both writer and visionary. There is no reason why they should be different in other ways, if the dedication is strong enough.

Until now most writers have concerned themselves with recording the anomalies and cruelties perpetrated by a skinflint world upon a good small man. Modern literature, for lack of a great aim, has become a Valhalla for those who shriek, beat their brows and weep more energetically than anyone else. As a device, hysteria is very useful for a writer, but as an end it becomes patently ludicrous. Any writer who resorts to such tricks without offering a ticket of destination is wasting his own time and the time of his readers, flouting the Zeitgeist in the most imbecilic fashion, and finally (I hope) cutting his own throat.

The truth of today is too plain for clear-thinking people to ignore, however uncomfortable it may be to the inherently lazy. We must grow larger . . . see further and deeper . . . think with more skill, concentration and originality—or become extinct. If we are not capable of meeting these seemingly unattainable requirements, writers such as myself will persist obstinately in trying to have things as we want them even if the words are finally addressed to the abyss rather than human faces. If the crusade is a hopeless one, it will be so only because there is nothing more impregnable than human weakness. This is an important conclusion, and its recognition offers three salient truths.

First, that a writer’s duty is to urge forward his society towards fuller responsibility, however incapable it may appear.

Second, a writer must take upon himself the duties of the visionary, the evangelist, the social leader and the teacher in the absence of other candidates.

Third, that he understands the impossible up-hill nature of a crusade and counters it by infusing in everything he creates a spirit of desperation.

This spirit of desperation is the closest approximation we can get to the religious fervour that brought about a large number of miraculous feats of previous, less reasonable, epochs. In desperation, as with religious exaltation, miracles, revelations and extraordinary personalities can be brought to everyday acceptance. The great advantage of it is that one can develop it to the point of being able to evoke it whenever there is cause for it.

I used the atmosphere of desperation in my first novel, The Divine and the Decay, very much in the way that a wind comes through an open door, throws a room into a sudden disarray, then leaves as abruptly. The wind in this case is a fanatic, and the room with an open door a small island community. As always in such cases, one is left perplexed and filled with a sense of indefinable outrage that has little to do with the disarray that must be restored to order. There is something maniacal about a really desperate man that welds him into a total unity and he becomes an embodiment of a single idea. Almost, dramatically speaking, flesh wrapped around an idea. Working for so long with desperation as my tool, I also learned about the merits of the lull, when the air vibrated with the foreboding of the next entrance. I relearned also a Greek lesson: how to turn presence into absence and absence into presence. But these details are worth mentioning only in relation to the use of desperation in contradistinction to the monotonous normality that most writers regard as the acme of reality.

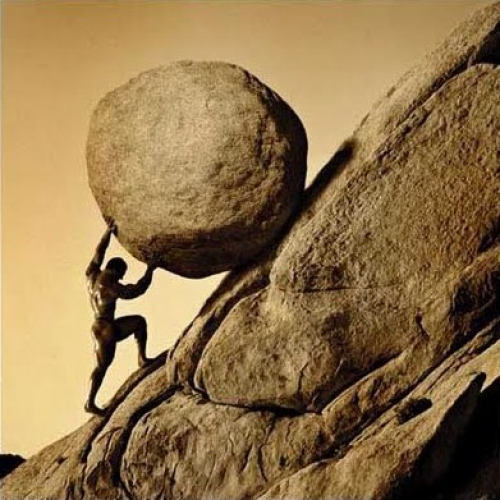

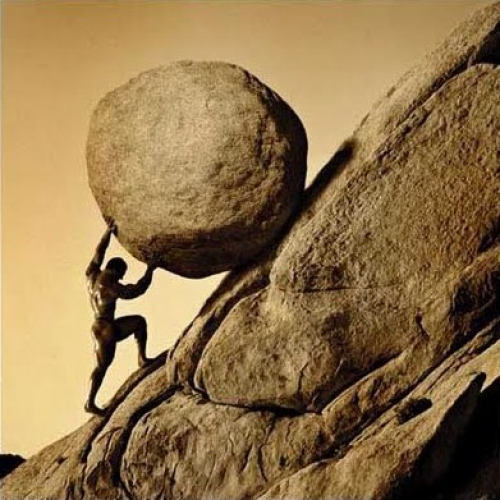

Desperation is the only attitude that can galvanize us from this lethargic non-living of ours. But without a calculated direction desperation is useless. Misadventures in its application can leave us dangerously drained of further effort. This is where the dramatization of aims is expressly the writer’s function. Consider the case of Sisyphus, whom the Gods had forever rolling that gigantic boulder of his up a hill and forever having it roll down again when he neared the top. The punishment was inflicted upon only too human strength. But with enough desperation the penalized king would not have attempted to roll it up after the first couple of attempts. He would have picked it up and flung it over the impossible crest, straight into the faces of his Olympian tormentors. I can think of many contemporary equivalents of the Sisyphean plight that are incessant defeats only because each of the sufferers refuses to rear up and wreck his opposition with the fury of desperation. To me, desperation is our immediate instrument, in the absence of belief, for collapsing this damnable, subhuman recognition of one’s surface limitations. Refuse to acknowledge them and the horizon spreads wide.

This cannot be done without examples, as I have said. The examples themselves can only be set by fanatics advancing be-yond the arena of human experience and knowledge. In a religious sense, the fanatic or writer goes into the wilderness, the first act of any visionary’s apprenticeship. Simultaneously, he becomes a social leader also, for humanity having to travel beyond the point where it now rests will only use paths already trodden.

New paths can only be created by writers with a desperate sense of responsibility. The only others capable of such a task are religious and philosophic minds, but unfortunately orthodoxy has ruined the first, and a desiccation debars the second. In resting the responsibility of human deliverance upon writers I am not calling for miraculous transitions antipathetic to their nature. Fundamentally, the writer has always been a prophet and a diviner in embryo. Centuries of ‘telling a jolly tale’ have simply caused him to let these other parts fall into disuse. I want their return, and I want them cultivated to full growth.

At the moment, the position of the writer in society is a difficult one. The good ones feel, quite rightly, that they should be antagonistic to authority; but the feeling is only a feeling and remains nothing more because few have got around to the point where they must begin wrestling with it. Because of this apprehension which is not turned into positive action, these writers find themselves nullified and abortive. They try to offset this predicament by an over-haughty pride in their isolation. More specifically they emphasize their artistic position to offset shortened powers, and offer a defensive facade of being icy intellectual pinnacles which, in actuality, spells death to their work if this attitude is carried to their desks.

To be exact, a writer is rather a ludicrous figure at work. He must be, to put himself in an arena with berserk bulls to gauge how much damage the horns can do. The gorings constitute literally the blood and tissue of his work; they are part of his empirical research into life. Perhaps research is too dignified a term for the tattered and bloody creature he becomes if he persists until he reaches the level of a good writer.

By such voluntary acts, he becomes an authority on the most fundamental subjects. Pain, for instance. It is not the politician, theologian or doctor who catalogues the depth, the range and the gamut of it, but the writer. He can state from personal knowledge that it has a hundred different pages, all written in different inks. Similarly, he is an expert in regions like agony, happiness, terror, exultation and whirling hope. These are his working neighbour-hoods.

He also knows from personal experiment the fine shades of violence; its velocity, trajectory and impact; its sources, and its quivering conclusions. When an accident is about to happen, let us say an aeroplane is plunging in a death dive, or a child is about to go under the wheels of a motor car, most eyes will be averted until it is over. But this is a luxury a writer simply cannot afford, and he will watch even if the object of study is someone he loves intensely. He has conditioned himself to observe everything that happens within his orbit with a steady and remembering eye. As his craft is produced at first-hand, constantly in positions of physical and mental hardship, for him the step towards vision and leadership is not a large one.

On the face of it, it seems ironical that a writer who goes to such lengths to learn this abnormal craft should use it only for the purpose of entertaining. But most are given little choice to be anything else with the shadow of destruction hanging over them. The few writers who would like to create heroic work are discouraged in advance, for they cannot be sure of even polite credulity on the part of readers. All ambitious contemporary writers are haunted by the thin, peaky face of the rational reader who peruses his literature with the pursed lips of a confirmed sceptic. Anything larger than his own life is anathema to this gentleman. Authors know it well and go in dread of him. This is why only a foolhardy few dare create anything but the slightest, most prosaic structures. The heroic, the bizarre, the moral and religious fabrics, have been torn down in the interests of reality. If the realities were large there would be little ground for complaint, but what is considered to be real by the normal canons of judgement is, of course, as confined as candlelight. It is not surprising that creative thinking today operates upon candle-power.

The situation is so bad that many leading writers have fallen to mocking their own ability to serve ‘fodder to pygmies’. They are proud of the ingeniousness they have developed over the course of time in feeding sly pieces of originality with every hundredth spoonful, done so skilfully it passes almost unnoticed. It is the bare remnants of creative pride. In another age a man could be a master; today he must be a midget, breathing a sigh of relief every time he gets away with his creative crime unpunished. This attitude of contemptuous hostility between writers and readers is another symptom of the need for a rupture between life and literature. The writer cannot create as largely as he wants; the reader is incapable of belief. Unless this stalemate is broken and another game started, the chess pieces will be swept to the floor . . .

Let me take you into the theatre and make an illustration of tragedy. An infinite number of creators have visited this terrain for the purpose of laying their masterpieces. It is as studded with great monuments as a war cemetery. On one you will read Prometheus Bound, next to it, Agamemnon. Close by perhaps Oedipus Rex, and, among the newer additions, Hamlet, Macbeth and Faust. Death . . . broken dreams . . . disillusion . . . There are a thousand threads in the pattern of it, and no doubt there are persons who walk the streets of London, Berlin and New York with threads still unwound and unwritten in their minds. But tragedy, with all the multiplicity of permutations before its in-evitable curtain, has one basic demand. The downfall.

My difficulty is in imagining how an object can fall in any direction other than down. However, most thinking people today appear to find more difficulty in imagining any height superior to themselves. That brings us to the dilemma. If a tragic figure is to fall he obviously cannot fall a few inches and hope to capture our awe or our pity; his fall must be a considerable one. It never is, under the present conditions. As soon as the figure of prospective tragedy begins to climb over the heads of his audience, they insist he climb down again to a height where they can believe in him. The only exception to this is Jack and the Beanstalk. And Jack only gets away with it, I surmise, because his pantomime appears in the Christian season of drunkenness and makes a swift departure before sober judgements are restored.

If a hero cannot rise, he cannot fall; on this point of order such good rationalists as Galileo, Newton and Einstein will bear me out. Such a fall would be unnatural, ungravitational and illogical; in fact, there is no fall. And yet Tragedy must have it.

Very well, what is it that sets the proper height for a tragic descent? Put in this way, it is like discussing a ballerina’s artistry in terms of ballistics! Let us assert, however, that tragedy has always demanded the greatest height conceivable as an essential condition of the downfall. A lot of levels contribute to make up this total height. The height is created by an outraged spiritual understanding, a shattered moral code and the complete social abasement of the protagonist. The downfall is darker than death; and often death is willingly chosen in preference to it, indeed as the very palliative of it when the intensity of anguish produced becomes fully manifest.

But these platforms of consciousness are ridiculously archaic to the modern world. The religious, moral and social heights have become melodramatic and unintelligent, beside the more modern concentration on the significance of a man’s facial twitches under psychoanalysis. For that, we have banged our windows shut on Heaven and locked the cellar door on Hell. We have foreshortened our intelligence accordingly. The result is that Oedipus Rex, Prometheus Bound, Hamlet, Macbeth and Faust would not only be laughed out of our London theatres if they were written today but, in truth, would be impossible to write today unless my thesis for creating fresh belief finds more general acceptance. Until it has, our own contribution to tragedy’s magnificent cemetery is a headstone inscribed: No More Tragedies. By it, we have created a tragedy infinitely more tragic than anything by Aeschylus, Shakespeare or Goethe.

The only indulgence to tragedy on the London stage is accorded to Shakespeare, whose vintage has removed him beyond the critical appraisals of the cognoscenti. The Shakespearian seasons that continue ad nauseam in the Waterloo Road serve as final evidence that the only good writer is a dead one. While the Old Vic flourishes as a salve to the national conscience, the absence of new tragedy is concealed from all but those who love and care for the theatre. The phenomenon of the Old Vic is the story of the Orthodox Church hardening its arteries against fresh truths all over again. Just as the Church is content with past visionaries and anachronistic dogmas, the theatre brandishes dead playwrights as its testament of greatness. In either case the result is bad. The sad and obvious truth about the titans of the past is that Aeschylus did not know the meaning of world over-population; Goethe was in the dark about guided missiles; Shakespeare was a complete idiot on the question of nuclear fission. The only writers competent to deal with these present-day problems are writers who are alive!

I believe that this civilization of ours requires cement to stop its crash until a new civilization is developed. Its great need, ultimately, is for a new religion to give it strength. In the meantime we urgently need a philosophy to span the gaps in our society that grow wider every day. But a philosophy and a religion can be evolved only by a new leadership. The possibility of such leaders depends solely on whether we can produce men capable of thinking without rule or precedent. Apart from writers with phenomenal powers of dedication, I cannot see the likelihood of such men emerging in time to meet the oncoming crises.

For these reasons, I believe that literature must be the cradle of our future religion, philosophy and leadership. In this belief I see the writer filling the paramount role if our civilization is to survive.

Related

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

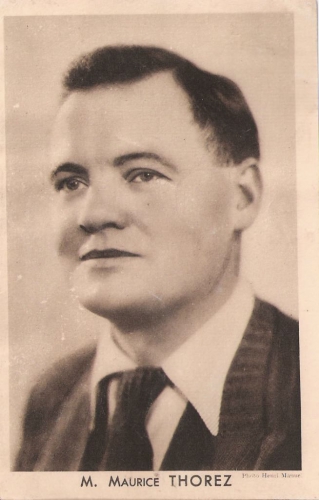

The initial response of the communists was indifferent. PCF leader Maurice Thorez stated that there was “ no difference between bourgeois democracy and fascism. They are two forms of capitalism . . . Between cholera and the plague one does not choose.” On the 7th of February, the PCF rejected a socialist overture to form a united front against what was widely perceived as a Fascist coup attempt.

The initial response of the communists was indifferent. PCF leader Maurice Thorez stated that there was “ no difference between bourgeois democracy and fascism. They are two forms of capitalism . . . Between cholera and the plague one does not choose.” On the 7th of February, the PCF rejected a socialist overture to form a united front against what was widely perceived as a Fascist coup attempt. Worker support for the People’s Front government was further eroded in 1937 following the rise of the fascist Parti Sociale Français (PSF). Following the fatal shootings of six workers by policemen in an anti-fascist demonstration at Clichy on March 16th, which lead to a call for a half-day strike in protest of the killings, Blum threatened to resign if the strike went ahead, and then failing to do so, ordered the police to crackdown on the workers who allegedly instigated the violence at Clichy.

Worker support for the People’s Front government was further eroded in 1937 following the rise of the fascist Parti Sociale Français (PSF). Following the fatal shootings of six workers by policemen in an anti-fascist demonstration at Clichy on March 16th, which lead to a call for a half-day strike in protest of the killings, Blum threatened to resign if the strike went ahead, and then failing to do so, ordered the police to crackdown on the workers who allegedly instigated the violence at Clichy.

Hostile aux États-Unis d’Europe ou à une Europe intergouvernementale, l’auteur préconise un État européen, « fédération de régions (p. 148) ». Notons au passage qu’il méconnaît ou dévalorise le concept traditionnel d’Empire dont il fait un contresens évident. C’est regrettable, car son approche de la Res Publica europensis coïncide largement avec l’idée impériale européenne.

Hostile aux États-Unis d’Europe ou à une Europe intergouvernementale, l’auteur préconise un État européen, « fédération de régions (p. 148) ». Notons au passage qu’il méconnaît ou dévalorise le concept traditionnel d’Empire dont il fait un contresens évident. C’est regrettable, car son approche de la Res Publica europensis coïncide largement avec l’idée impériale européenne.

Celui qui l’a appris à ses dépens, c’est un Néo-Zélandais, gérant de bar en Birmanie (Myanmar, SVP), un certain Phil Blackwood, condamné à deux ans et demi de prison pour avoir portraituré Bouddha avec des écouteurs sur la tête, juste histoire de faire de la publicité pour son bar, « lounge », évidemment. Eh oui, le bouddhisme, ce n’est pas forcément la fête du slip tous les dimanches. Le Phil Blackwood en question a eu beau s’excuser, battre coulpe et montrer patte blanche : pas de remise de peine et case prison direct.

Celui qui l’a appris à ses dépens, c’est un Néo-Zélandais, gérant de bar en Birmanie (Myanmar, SVP), un certain Phil Blackwood, condamné à deux ans et demi de prison pour avoir portraituré Bouddha avec des écouteurs sur la tête, juste histoire de faire de la publicité pour son bar, « lounge », évidemment. Eh oui, le bouddhisme, ce n’est pas forcément la fête du slip tous les dimanches. Le Phil Blackwood en question a eu beau s’excuser, battre coulpe et montrer patte blanche : pas de remise de peine et case prison direct.

The Greeks, unlike ourselves, expected their literary men to be thinkers and teachers as a matter of course. This expectation was justified by figures of the stature of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides. Dramatists like these preached, taught, entertained and prophesied with such vitality and authority that their judgements were taken away by their audiences and applied to all levels of civic life. That both playwrights and audiences prospered upon this didactic relationship is best shown by the intellectual versatility of the Hellenic world, which has yet to be repeated.

The Greeks, unlike ourselves, expected their literary men to be thinkers and teachers as a matter of course. This expectation was justified by figures of the stature of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides. Dramatists like these preached, taught, entertained and prophesied with such vitality and authority that their judgements were taken away by their audiences and applied to all levels of civic life. That both playwrights and audiences prospered upon this didactic relationship is best shown by the intellectual versatility of the Hellenic world, which has yet to be repeated. When the Roman Empire rose to take its place, Terence and Seneca, the bright lights of Latin, reflected a frightening deterioration in what was expected of a writer. Julius Caesar found it an easy matter to be both a swashbuckler and a scribe in a world that, culturally, could not even conquer sculpture. But Rome’s poverty was magnificence compared to the bankruptcy prevailing in Britain and everywhere else in the civilized world today.

When the Roman Empire rose to take its place, Terence and Seneca, the bright lights of Latin, reflected a frightening deterioration in what was expected of a writer. Julius Caesar found it an easy matter to be both a swashbuckler and a scribe in a world that, culturally, could not even conquer sculpture. But Rome’s poverty was magnificence compared to the bankruptcy prevailing in Britain and everywhere else in the civilized world today.