“Great things are done when Men & Mountains meet / This is not Done by Jostling in the Street,” wrote William Blake.

The modern world suffocates the soul of humankind. Matter longs for the embrace of soul, just as the unborn is ensheathed in the mother’s womb; and the soul desires the caress of matter, just as a newborn is cradled in the mother’s arms. Every moment is the nondual experience of gestation and birth of soul into matter, matter into soul. Modern life severs this connection as carelessly as the assembly line obstetrician prematurely severs the umbilical cord that still carries vital nutrients from mother to child. We are weighed upon scales imbalanced by ceaseless activity and insidious apathy, our hearts faint with anxiety and our bodies dead with the weight of indifference.

How do we reconnect with the primordial source in a decentered and displaced world?

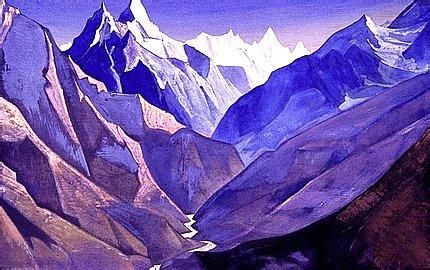

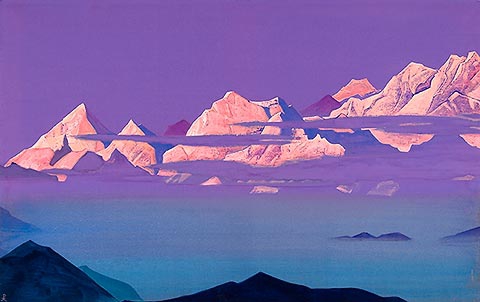

The spiritual quest of the higher person is the path that leads one on a journey to reunite with divine nature, and there are few greater paths to accelerate this reunification than the experience of the mountains. Amongst the peaks one transforms from a rank-and-file soldier of modernity into a Grail Knight—a golden embryo shining in the dark cosmic womb of creation.

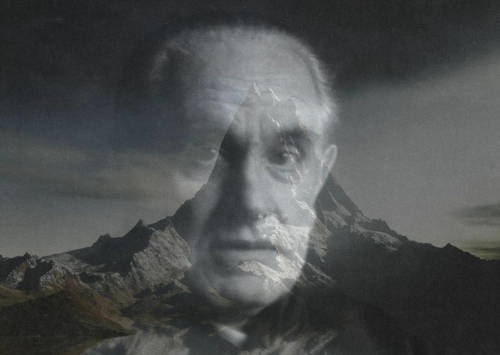

In Meditations on the Peaks, Julius Evola wrote:

In the struggle against mountain heights, action is finally free from all machines, and from everything that detracts from man’s direct and absolute relationship with things. Up close to the sky and to crevasses—among the still and silent greatness of the peaks; in the impetuous raging winds and snowstorms; among the dazzling brightness of glaciers; or among the fierce, hopeless verticality of rock faces—it is possible to reawaken (through what may at first appear to be the mere employment of the body) the symbol of overcoming, a truly spiritual and virile light, and make contact with primordial forces locked within the body’s limbs. In this way the climber’s struggle will be more than physical and the successful climb may come to represent the achievement of something that is no longer merely human. In ancient mythologies the mountain mountain peaks were regarded as the seats of the gods; this is myth, but it is also the allegorical expression of a real belief that may always come alive again sub specie interioritatis.

Meditations on the Peaks (English translation available from Inner Traditions) is a collection of Evola’s writings on the spiritual quest of mountain climbing. While not free of the commodification of the modern sporting life (one only need to look at the resort towns inviting crass hordes of weekend warriors that contaminate the regions for a reminder), the mountains offer potential for the spiritual conquest of self-overcoming. By training the body, purifying the soul and cultivating a reverence for mortality, one may, with iron will and monumental discipline, ascend the peaks in contemplation of their silent, still and divine majesty.

Evola presents mountain climbing as a Yoga of the scholar and the athlete. The modern world has divided the intellectual and athletic pursuits, creating a false dichotomy of “nerds” and “jocks” that predominates the industrialized West. Either the body atrophies for feint intellectual praise and bourgeois academic prestige, or the mind suffers for the pursuit of empty competition and physical achievement. In this dichotomous framing of brains against brawn, both scholar and athlete lose touch with the metaphysical reality that study and training develops. It is among the peaks where this division is erased. Evola wrote:

[A]mong sports, mountain climbing is certainly the one that offers the most accessible opportunity for achieving this union of body and spirit. Truly, the enormity, the silence, and the majesty of the great mountains naturally incline the soul toward that which is greater than human, and thus attract the better people to the point at which the physical aspect of climbing (with all the courage, the self-mastery and the mental lucidity that it requires) and an inner spiritual realization, become the inseparable and complementary parts of one and the same thing.

At the heart of Evola’s study of the peaks is the eleventh century Tibetan Buddhist sage Milarepa. Credited with the revival of metaphysical doctrine within the Mahayana school of Buddhism, Milarepa’s teachings were known in the form of songs describing episodes of his life that remained within the current of oral tradition until modern times.

One day, Milarepa journeyed into the mountains for ascetic retreat. When six months had passed without seeing their teacher, Milarepa’s disciples had assumed that he had fallen victim to a brutal snowstorm, caught without food against the unforgiving elements. In their mourning, his disciples made sacrificial offerings prescribed for the dead. When spring arrived, they went to search for him. During their journey, they were astonished when they saw a snow leopard that transformed into a tiger. As they entered the Cave of the Demons, they heard a singing voice that they immediately recognized as their teacher’s. It was Milarepa who had projected the images of the leopard and the tiger, having sensed his disciples approaching. He told his disciples that although he went a long time without food he did not hunger, for he gained sustenance from the offerings they made for him.

Upon returning home, Milarepa explained how he was able to “endure the elements, the icy temperatures, and raging wind, thus overcoming the invisible forces (the ‘demons’) disguised as snow,” thusly singing:

The snowfall was beyond all measure. Snow covered the Whole mountain and even touched the sky, falling through the bushes and weighing down the trees.

In this great disaster I remained in utter solitude. The snow, the wintry blast, and my thin cotton garment fought against each other on the white mountain. The snow, as it fell on me, turned into drizzle. I conquered the raging winds, subduing them to silent rest.

The cotton cloth I wore was like a burning brand. The struggle was of life and death, as when giants wrestle and sabers clash.

I, the competent yogi, was victorious; my power over the vital heat (tumo) and the two channels was thus shown. By observing the Four Ills caused by meditation and keeping to the inner practice, the cold and warm pranas became the essence. This was why the raging wind grew tame and the storm, subdued, lost its power.

Not even the devas’ army could compete with me. This battle, I, the yogi, won.

These are the harsh conditions one must endure on the merciless path of higher spirituality. Abandoning the world in cosmic isolation, the seeker must withstand the chaotic conditions of an unrestrained cosmos through the power of their own inner flame. It is during times of great peril, whether alone atop a physical mountain or abandoned to the darkest predilections of life, when we must light the fire of our crucible and burn away within. One might be left for dead, but will gain sustenance from the offerings of mourners as the unborn child receives nutrients from the mother. For it is in these most rugged and unforgiving of conditions that we return to the cosmic womb of creation, where all dross and detritus burns away and we emerge purified and renewed.

To this day, Evola remains a controversial figure in metaphysical circles. Mention of his name is enough to incite neo-McCarthyist accusations of fascist tendencies or a mistaken sympathy amongst white national racialists. Owing perhaps to the ever widening gulf between spirit and body, it is near impossible nowadays to balance an admiration for a great scholar’s superlative body of work with a reservation of their difficult political views without finding oneself in the snake pit of guilt by association. As the body is further estranged from the spirit, both will descend into a pit of decadent self-pleasure, and find anathema anything which challenges one to greater heights. Evola’s ideas are dangerous. But, like the mountains, so too is the spiritual quest. As the great mountaineer Reinhold Messner said, “The mountains are not fair or unfair, they are just dangerous.”

Messner is one of the best exemplars of the discipline cultivated on the path of higher spirituality. He is the first individual on record, along with Peter Habeler, to ascend Mount Everest without supplemental oxygen. Messner is also the first climber to ascend all fourteen of the eight-thousanders, mountains located in the Himalayan and Karakoram ranges with peaks exceeding 8,000 meters (26,247 ft) above sea level. These are peaks that are well above the “death zone,” altitudes where the amount of oxygen is insufficient to sustain human life. Messner’s records are not the same as the medals won by competing athletes; they are physically intangible totems, cairns left on the path toward mastery. Eschewing the commodification of the modern world, Messner is the paragon of peak physical, mental and spiritual development.

The mountains remain a testament of spiritual initiation in the modern era. Populations will grow and disappear, cultures will spread and vanish, and civilizations will rise and fall, but the mountains will keep still for centuries. The timeless stability of the mountains is what has attracted spiritual seekers to them since the dawn of human culture. In this still and silent wilderness, where the body of man is at the mercy of both nature and the gods, we find the foundation to build the inner sanctum. When in the mountains, an ascetic like Julius Evola or a libertine like Aleister Crowley both find the sanctuary they seek. At these altitudes, it matters not what your opinions are or who they offend, but how well you have conditioned the body and trained the mind.

“The mountain requires purity and simplicity,” Evola wrote, “It requires asceticism… In this context, the mountainous peaks and the spiritual peaks converge in one simple yet powerful reality.

Meditations on the Peaks is published by Inner Traditions and available from their website or from Amazon.com and other booksellers.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les commentaires sont fermés.