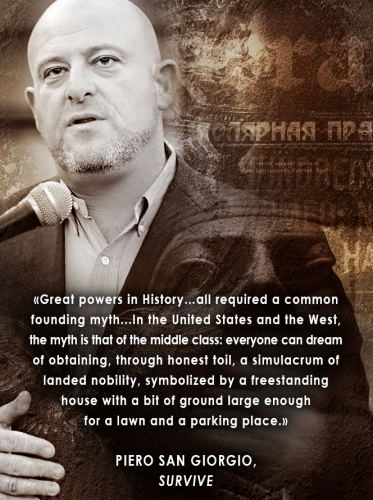

Piero San Giorgio

Survive—The Economic Collapse: A Practical Guide

Radix/Washington Summit Publishers, 2013

For White Nationalists, the possibility of some of kind of civilizational collapse not only seems plausible, but is also an exciting prospect as it poses an opportunity to make things right again. We know that the current system is cemented together with falsehoods. We can see that the money system is fraudulent. We understand that the “Gods of the Copybook Headings” will one day return with “terror and slaughter.” What made Western Civilization great—true leaders with an ability to plan for the long term—have been abandoned in favor of panderers who appeal to the short-sighted demands of a foolish public. We feel that this trajectory toward ever greater folly cannot last. Surely, it must not last! With this knowledge the question arises: What do we do in the meantime? Perhaps, Swiss author, Piero San Giorgio can help us find an answer.

For White Nationalists, the possibility of some of kind of civilizational collapse not only seems plausible, but is also an exciting prospect as it poses an opportunity to make things right again. We know that the current system is cemented together with falsehoods. We can see that the money system is fraudulent. We understand that the “Gods of the Copybook Headings” will one day return with “terror and slaughter.” What made Western Civilization great—true leaders with an ability to plan for the long term—have been abandoned in favor of panderers who appeal to the short-sighted demands of a foolish public. We feel that this trajectory toward ever greater folly cannot last. Surely, it must not last! With this knowledge the question arises: What do we do in the meantime? Perhaps, Swiss author, Piero San Giorgio can help us find an answer.

There is a saying attributed to Louis Pasteur and paraphrased by several survivalists I know, “Chance favors the prepared mind.” The only thing certain in the event of a major collapse is that chaos will ensue. Survival in such a situation is a matter of being in the right place at the right time, but if you have worked out the various possible scenarios in advance and know how you will respond to each, then you may have a slight advantage. In Survive—The Economic Collapse: A Practical Guide, San Giorgio describes a number of collapse scenarios with varying degrees of severity, and then provides a basic overview of the factors that an amateur survivalist should consider in preparation for doomsday.

The first part Survive is entitled “Risks and Impacts” and begins with some eye-opening numbers regarding overpopulation and the rate of human reproduction on planet earth. People often forget that two centuries ago there were only about a billion people living on the planet. It took the human species approximately 200,000 years to number a billion people. Then, in only 200 years that number has increased seven-fold. When considering this reality, it is almost laughable to hear environmentalists claim that there is an urgent need to pass legislation to reduce the use of fossil fuels. If climate change poses the threat that is often claimed, then it just as much due to the population explosion we have witnessed in the last few decades.

You will be hard pressed to find a mainstream environmentalist proposing that we need to pass legislation to reduce birth rates worldwide, particularly among those most likely to be poor stewards of the earth’s resources. It is very common for the same environmentalists obsessed about fossil fuel legislation to insist that every Third World resident who “dreams” hard enough has a human right to settle in the United States, and these immigrants deserve to be given the First World lifestyle to which Americans have become accustomed with all of its consumption and waste. These brainwashed fools fail to understand that what the planet really needs are fewer human rights and more eugenics programs. This view is not endorsed in the book, but anyone who thinks seriously about overpopulation should not dismiss eugenics as a necessary measure.

Of course, exponential population growth leads to problems beyond global climate change and polluted air, water, and soil. San Giorgio predicts the exhaustion of all vital natural resources in the next 40 years. While I cannot state for certain his numbers are accurate, the theory certainly bears consideration. The earth has a finite number of resources that are being consumed at an ever-increasing rate as the standard of living rises around the globe. It makes sense that at some point these resources will run out. If we fail to use them wisely then we, as a species, we will create a terrible and tragic situation for ourselves or our descendants.

In addition to simply using up natural resources, we are in the process of destroying the cultures that allowed humanity to thrive in the first place. San Giorgio writes:

Culture appears in the word “agriculture” for a good reason. This culture, or cultivation of the earth—I would even say, this love of the earth—is made up of knowledge, competence, tricks, secrets, work methods acquired over centuries and transmitted with care—and, indeed love—to the next generation, from father to son, from mother to daughter.

In less than a century, blinded by the ease fossil energy has brought us, we have thrown all that knowledge away. We have transformed farms into automated factories. Agriculture has gone from family and community management to an industrial and global enterprise.

One question that comes to mind is whether the ease and comfort brought to our daily lives by industrial technology are really worth the trade-off. Has the quality of life improved now that more people can spend their free hours watching television and eating processed foods? Perhaps we would be better off reserving the accessibility of complex technologies to only a select few charged with discovering the mysteries of the universe. The vast majority of people might enjoy an honest days’ work outdoors more than a process-oriented job in a grayish-brown cubicle, or telling stories around a fire rather than sitting in their living room marathoning The Walking Dead on Netflix.

Another risk discussed in the first part of the book is the problem posed by the financial system, how money is created and how this could lead to a potential collapse. This is followed by a critique of globalization, which states the rate of change in a global society requires such rapid adaptation that it cannot be done in a healthy way. Humans are being demanded to give up the aspects of our societies that have made life worth living for generation after generation—the rootedness that we have in our identity as a culture and people—and for what? So that we can become cogs in a giant and seemingly meaningless mechanism, and for most people, there is no choice in the matter. Becoming a cog is necessary if we want to meet our basic needs for survival. This is what “Liberalism” has wrought.

The first part ends with a chapter called “Hopes” to help alleviate the nightmares those of us who read before bed may have been having. For San Giorgio, there is hope to be found in the prospect that another way of life is possible, one that requires radical transformation. He writes:

Instead of trying to get a car to run on something other than gasoline, it is time to reflect on a way of life without cars. The social structure is going to have to evolve; we’re going to have to get rid of bad habits and accept limits: we cannot, for example, make commercial airlines fly on electricity, just as we don’t mold titanium turbines with electricity. It is our habits and culture as a whole that must change. Without new values, we will not succeed.

Yet how can such a shift in values take place when it seems that we are in the multifaceted death spiral the author has previously detailed for us? Life has been jarred out of balance and balance must be restored. To put it another way, justice must be made manifest. In human interactions there can be no justice without power. During the last century, the period on which San Giorgio focuses in pointing to where we went wrong, power has been in the hands of the unjust. Power must be reclaimed by those who will do what is right. This cause is at the heart of White Nationalism and the ethnonationalist moral system that the movement advances.

But Piero San Giorgio is not a White Nationalist. He endorses a small scale, almost pre-political-system of preparedness and self-sufficiency, rather than investing in any movement that pursues sweeping political change. In this sense he is banking on “The Collapse” for the shift in values upon which he has rested his hopes. And “The Collapse” is the title the second part of the book.

In Part II the mechanisms of collapse are more closely examined. In short, as the global industrial and economic system becomes more complex it also becomes more fragile. If one part of the system falters this could lead to the breaking point. Different crises are discussed, in which one part breaks. In a section about the Food Crisis, San Giorgio writes, “It takes 1500 liters of gasoline per inhabitant per year to feed a Westerner. To produce a calorie of food, the equivalent of 10 calories of fossil fuel is needed, whether directly (fuel) or indirectly (electricity, etc.)” This equation cannot be sustainable with a finite amount of fuel in the world. Another factor in the food crisis is the depletion of nutrients in the soil caused by factory farming. But factory farming is necessary to feed the population at its current size.

Countries and regions that rely on the importation of food will be the first to suffer as it becomes scarcer due to a convergence of factors exacerbated by short term planning, and this in turn will lead to a breakdown of the global system. A social crisis will emerge due to antipathy between groups competing to survive, and as social cohesion deteriorates we will see the breakdown of the infrastructure that maintains our current standard of living. Sanitation systems and nuclear power plants are examples of infrastructure that require continuous maintenance. If sanitation systems are neglected there will be a rapid rise in disease and a lack of drinking water. If nuclear power plants do not receive regular attention then there is the potential for another Chernobyl wherever they are found.

San Giorgio describes nine scenarios of how society might handle a collapse depending upon the rate of collapse and the extent of catastrophe. He calls the scenario with the slowest rate and smallest extent a techno-utopia. In this instance, technology continues to solve every resource problem, and the world becomes increasingly globalized. Social atomization advances at a steady pace, and the vast majority of people are medicated to cope with meaninglessness of existence. This is the best possible of scenarios for those who are addicted to comfort. Yet, it is also a collapse of many of the aspects of life that humans value. What is not mentioned here is the idea that when technology becomes complex enough, humanity could feasibly be replaced by artificial intelligence.

Another scenario that is predicted in the case of a slow rate of collapse but a great extent of catastrophe is described as eco-fascism, in which ”Deep Green” parties take over the government and enact strict controls to ensure the preservation of eco-systems. It is in this scenario that eugenics programs are given credence, with a permit being required to have children. Additional measures are described to save costs and reduce the population.

Deep Greens showed a willingness to use tactics that a prior generation would have called “ruthless.” In order to limit demand on the welfare system, the mentally handicapped and those with Down syndrome were systematically tracked down and euthanized. Seniors over the age of 60 were barred from the public health system. The euthanasia of the severely ill was made free and immediate, unless specifically forbidden by the family.

San Giorgio’s description of eco-fascists is reminiscent of the Tea Party’s predictions about Obamacare. As can be seen from the excerpt above, the future scenarios are written in the past tense as if they have already happened. They are fun to read, but then so is science fiction.

The final scenario described is the one with fastest collapse and the greatest extent of catastrophe, which is called Ragnarök. This might be caused by some unforeseen or unpreventable situation such as a comet hitting the earth. But even in such a dire case, the reality is that some humans would probably survive. We so are so numerous and so adaptable that the likelihood of our total extinction is small. In my opinion, it is smaller in a Ragnarök scenario than in one of techno-utopia. After discussing these possible futures, we are asked to consider our personal future and decide how important we think it is to be prepared for the worst. When considering the possibilities, we are told we are better off prepared than not, but of course the choice is up to us.

The fourth part of the book is entitled “Survival” and describes how to build what San Giorgio calls a Sustainable Autonomous Base (SAB). This is a secure space for which provisions have been made to ensure access to seven fundamental principles of survival, which are water, food, hygiene and health, energy, knowledge, defense, and the social bond. A chapter is dedicated to each of these principles. A well-planned SAB should be stocked with supplies for short term survival as well as the tools and equipment necessary to eventually live completely off the grid.

The tone of the book becomes more technical, like a manual. The amount of information can be overwhelming, and each chapter provides only a basic overview what kinds of thing one should consider surrounding these principles. For instance, in the food chapter, a list of foods that can be stored long term is provided along with suggestions for how much should be stocked for a year’s supply. Methods of preservation are also described and ways of procuring food once supplies run out, like hunting, fishing, and gardening. But only a few pages are dedicated to these broad concepts. A person serious about building an SAB will need to do a lot more research.

Few have the time or money to master every facet of an SAB. This is why knowledge is included as a principal of survival. Having a comprehensive physical library will be very useful for learning those things that the survivalist did not have time to study before a dire situation arises. The social bond is also important principle for this reason. San Giorgio recommends partnering with others to build an SAB. Preferably these partners should have a wide array of different skills, or can be assigned to become experts in one or several of the principles of survival.

Also falling under the social bond principle are ways of communicating with the outside world, be it locally or with the wider world via some type of radio communication. Protocols need to be developed regarding how outsiders should be treated. In a collapse scenario, there is a far greater risk of being open and neighborly, yet at the same time, being too security conscious could lead to missed opportunities.

The final section of the book is on how to begin preparation, including both mental preparation and the preparation of material needs. For mental preparation, San Giorgio recommends a media detox, such as going for a period of time without consuming any mass media. He also recommends getting rid of television altogether. Other exercises he mentions including going a weekend without electricity and water, going a week without food, or without money. He advises practicing certain social skills, like acting as a pick-up artist, or selling something, or negotiating something. He also describes a detailed 6-day preparation exercise, which incorporates many of the survival principles laid out in the previous section.

Survive—The Economic Collapse: A Practical Guide ends with a comprehensive bibliography and reference section. There is also a series of a useful appendices including one on how to make a 72-hour survival kit, and numerous lists of equipment and supplies needed for the more technical of the seven principles of survival. These final pages make an excellent starting place for anybody thinking about getting into survivalism.

Overall, this book looks and feels as though it is targeting young people. Each chapter opens with quotations from both historical figures, popular contemporary figures, and even some fictional characters, like Morpheus from The Matrix. Each chapter ends with a few fictional vignettes related to the subject of the chapter, which do not add much to the reading experience, but may be entertaining to some. The font of the text changes between the different components of the chapter, and some fonts have a cartoonish feel. It would not have been surprising to encounter a few comic strips, but with the exception of some graphs there are no illustrations in the book.

San Giorgio seems at least somewhat realistic about race, conceding that in a collapse situation racially diverse areas will have worse tension and distrust than homogenous areas. Furthermore, his critique of globalization includes some discussion of the problems created by mass immigration. The discussion of overpopulation also has some racial undertones, but these are not explicitly brought to light. There is no indication that San Giorgio understands the value of racial consciousness in the book, but given his situation and the subject matter, this makes sense. It is probably better for book sales to avoid talking about race.

There is something uniquely white about survivalism. Perhaps this is related to having a lower time preference on average, and seeing that the poor planning of today is creating a society that cannot last. Or perhaps there is a spiritual element related to our desire to achieve a balance with nature. Many readers of this book will find the notion of a Sustainable Autonomous Base appealing even if an economic collapse never occurs. Just the idea of living sustainably and autonomously away from this sick anti-culture that surrounds us will no doubt inspire some to become of survivalists.

One outcome of building an SAB is that it requires us to recreate a culture that is healthy through the mastering of skills and techniques that are quickly disappearing from our everyday lives; the ability to grow our own food and make our own clothing, tools, shelters and energy sources; the ability to protect ourselves. If we partner with others toward these goals we can build trusting and tightly-knit relationships, possibly with other white people who may not agree with us at first. But once that trust has been gained this can be the foundation for a new understanding about racial identity. And of course, we should continue to engage in propaganda tactics to bring about an awakening of racial consciousness among our kin. While the future is unclear, two things are certain: the system must change, and white people must defend themselves.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg