In saner times our great poets, writers, and philosophers expressed the feelings and ideas which came naturally from the race-soul. In these times those feelings and ideas are too “controversial” to be expressed freely, so where they cannot be suppressed outright, they are reinterpreted, obscured, and selectively anthologized by the alien arbiters of our culture. For no poet of our race has this been more true than for William Butler Yeats.

In saner times our great poets, writers, and philosophers expressed the feelings and ideas which came naturally from the race-soul. In these times those feelings and ideas are too “controversial” to be expressed freely, so where they cannot be suppressed outright, they are reinterpreted, obscured, and selectively anthologized by the alien arbiters of our culture. For no poet of our race has this been more true than for William Butler Yeats.

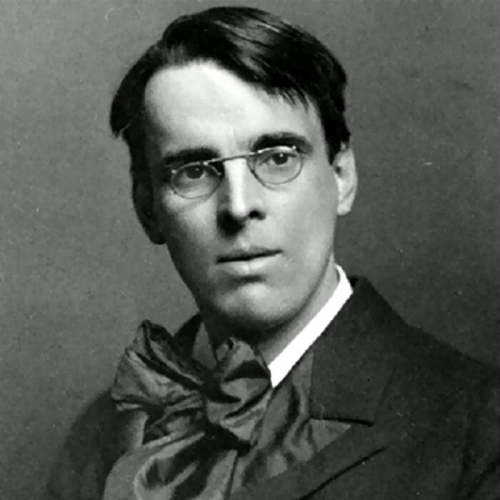

William Butler Yeats was probably the greatest poet of the modern age; T. S. Eliot acknowledged as much. His roots were deep in Ireland, but, withal, he embodied the questing spirit of the whole of Western culture.

It is impossible without writing a volume (or two) to render even a partial appreciation of his many-faceted life and work. He was born into the Irish Protestant tradition, of that line which included Swift, Burke, Grattan, Parnell. He was poet, playwright, guiding spirit of the famed Abbey Theatre, essayist, philosopher, statesman, mystic. But, as he once wrote, “The intellect of man is forced to choose “Perfection of the life, or of the work” ["The Choice"], and it is primarily in his poetry that most people seek an understanding of his genius.

Some of his views confounded the mediocre, left-wing poets and intellectuals who sought him out in his later years. Unable, of course, to ignore him, they attempted to appropriate him as their own, much as Walter Kaufmann, a Jew, attempted to do with Friedrich Nietzsche some years later. Thus, many writings about Yeats totally ignore his more “controversial” ideas, or at best refer to them only obliquely.

For example, Yeats believed in reincarnation, not only in a poet’s way, as a dramatic symbol. but quite literally: the individual human spirit remained a part of the collective race-soul even after the body died, and as long as the race endured the individual spirit might re-emerge later in another body. In an early poem, written when he was about 24, we have:

“Ah, do not mourn,” he said,

‘That we are tired, for other loves await us;

Hate on and love through unrepining hours.

Before us lies eternity; our souls

Are love, and a continual farewell.

– “Ephemera”

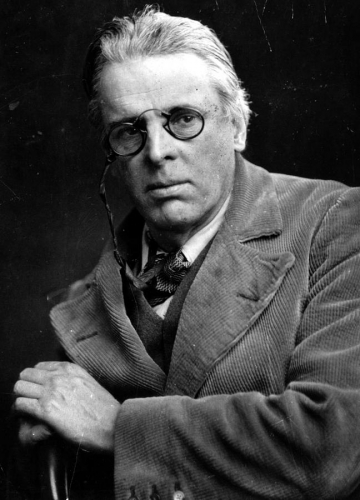

And just a few months before his death in 1939 at age 73, with matured powers of creative expression:

Many times man lives and dies Between his two eternities,

That of race and that of soul,

And ancient Ireland knew it all.

Whether man die in his bed

Or the rifle knock him dead,

A brief parting from those dear

Is the worst man has to fear.

Though grave-diggers’ toil is long,

Sharp their spades, their muscles strong,

They but thrust their buried men

Back in the human mind again.

– “Under Ben Bulben”

Modern liberalism and democracy were anathema to Yeats’s aristocratic spirit. He was a good friend of Ezra Pound. He was associated for a time with the Irish Blueshirts, led by General O’Duffy, and he wrote some marching songs for them. He spoke of “Mussolini’s incomparable Fascisti” (although being the kind of man he was he recoiled somewhat from the demagogic elements of fascist movements).

He read widely and avidly on race, eugenics, Italian Fascism, and German National Socialism. On eugenics, according to his biographer, Yeats “spoke much of the necessity of the unification of the State under a small aristocratic order which would prevent the materially and spiritually uncreative families and individuals from prevailing over the creative.”[1] Eugenics, to Yeats, had both physical and spiritual aspects, It is touched upon in some of the poems. In “Under Ben Bulben” he wrote:

Poet and sculptor, do the work

Nor let the modish painter shirk

What his great forefathers did,

Bring the soul of man to God,

Make him fill the cradles right.

Irish poets, learn your trade,

Sing whatever is well made

Scorn the sort now growing up

All out of shape from toe to top,

Their unremembering hearts and heads

Base-born products of base beds.

A much earlier poem reads:

All things uncomely and broken, all things worn out and old,

The cry of a child by the roadway, the creak of a lumbering cart,

The heavy steps of the ploughman, splashing the wintry mould,

Are wronging your image that blossoms a rose in the deeps of my heart.

The wrong of unshapely things is a wrong too great to be told;

I hunger to build them anew and sit on a green knoll apart,

With the earth and the sky and the water, re-made, like a casket of gold.

For my dreams of your image that blossoms a rose in the deeps of my heart.

– “The Lover Tells of the Rose in His Heart”

Yeats did not write for scholars, but for the people, and schoolchildren throughout the English-speaking world are familiar with at least a few of his works–or, perhaps, just a line or a phrase from them. Many youngsters have recited in school this verse by the young Yeats:

Down by the salley gardens my love and I did meet;

She passed the salley gardens with little snow-white feet.

She bid me take love easy, as the leaves grow on the tree;

But I, being young and foolish, with her would not agree.

– “Down by the Salley Gardens”

Another favorite is ”The Lake Isle of Innisfree.” During his many tours of the United States, every American audience insisted he recite it for them:

I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattle made:

Nine bean-rows will I have there, a hive for the honeybee,

And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

Nearly as familiar is the stark vision of “The Second Coming”:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in the sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches toward Bethlehem to be born?

People with a liberal mind set have often quoted this last poem, but some do so with a certain amount of unease, and rightly. Accepting historical necessity, Yeats is not, as the American Jewish critic Harold Bloom pointed out, necessarily averse to this “rough beast.”[2]

Thus, liberal critics are never completely comfortable in the company of Yeats. In “Under Ben Bulben,” one of Yeats’s last poems and a general summary of his ideas, he writes:

You that Mitchel’s prayer have heard

“Send war in our time, O Lord!”

Know that when all words are said

And a man is fighting mad,

Something drops from eyes long blind,

He completes his partial mind,

For an instant stands at ease,

Laughs aloud, his heart at peace.

Even the wisest man grows tense

With some sort of violence

Before he can accomplish fate,

Know his work or choose his mate.

Bloom charged that Yeats “abused the Romantic tradition” in these lines. But Yeats would have shown Bloom the contempt he deserves; in one of Yeats’s letters we can read: “I am full of life and not too disturbed by the enemies I must make. This is the proposition on which I write: There is now overwhelming evidence that man stands between eternities, that of his family and that of his soul. I apply those beliefs to literature and politics and show the change they must make. . . . My belief must go into what I write, even if I estrange friends; some when they see my meaning set out in plain print will hate me for poems which they have thought meant nothing.”

Earlier Yeats had written of war, politics, and pleasant but self-defeating illusions. In “Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen” he surveyed both the halcyon pre-World War I years and the grim aftermath of war, civil war, and revolution:

We too had many pretty toys when young:

A law indifferent to blame or praise,

To bribe or threat; habits that made old wrong

Melt down, as it were wax in the sun’s rays;

Public opinion ripening for so long

We thought it would outlive all future days.

O what fine thoughts we had because we thought

That the worst rogues and rascals had died out. . . .

Now days are dragon-ridden, the nightmare

Rides upon sleep: a drunken soldiery

Can leave the mother, murdered at her door,

To crawl in her own blood, and go scot-free;

The night can sweat with terror as before

We pieced our thoughts into philosophy,

And planned to bring the world under a rule,

Who are but weasels fighting in a hole.

Yeats himself did not take an active part in the Irish civil war, and he may have felt a certain uneasiness about the physical side of the struggle:

An affable Irregular,

A heavily-built Falstaffian man,

Comes cracking jokes of civil war

As though to die by gunshot were

The finest play under the sun.

– “Meditations in Time of Civil War”

Yeats, it is true, spent much time contemplating and expressing himself on the great problems of the age and of the individual living in this age, but he never strayed far from whimsy. As typical of his poetry as anything he wrote is the neatly lyrical “To Anne Gregory,” addressed to the granddaughter of his friend and fellow playwright Lady Augusta Gregory:

“Never shall a young man,

Thrown into despair

By those great honey-colored

Ramparts at your ear,

Love you for yourself alone

And not your yellow hair:

“But I can get a hair-dye

And set such color there,

Brown, or black, or carrot,

That young men in despair

May love me for myself alone

And not my yellow hair.’

“I heard an old religious man

But yestemight declare

That he had found a text to prove

That only God, my dear,

Could love you for yourself alone

And not your yellow hair.”

I know of no English or American poet writing today who can approach even remotely Yeats’s lyrical power or his poetic shaping of strong and startling ideas. Most of today’s poets are professors of English or fine arts who grind out pedestrian or pretentious drivel, presumably for prestige within the academic community. And it is hardly conceivable that there are any campus publications, literary or otherwise, that would publish all of Yeats’s material were he writing today. What, for instance, would they do with these lines from “John Kinsella’s Lament For Mrs. Mary Moore”?:

Though stiff to strike a bargain,

Like an old Jew man,

Her bargain struck we laughed and talked

And emptied many a can . . . .

Perhaps Yeats was the culmination of that great, surging Romantic wave, now in recession.

Though the great song return no more

There’s keen delight in what we have:

The rattle of pebbles on the shore

Under the receding wave.

– “The Nineteenth Century and After”

Perhaps. And perhaps a revitalized and resurgent West can at least produce poets in the great tradition, who refuse to wallow in mud and make a career of destroying our language.

Sing the peasantry, and then

Hard-riding country gentlemen,

The holiness of monks, and after

Porter-drinkers randy laughter;

Sing the lords and ladies gay

That were beaten into the clay

Through seven heroic centuries;

Cast your mind on other days

That we in coming days may be

Still the indomitable Irishry.

– “Under Ben Bulben”

These lines also proved upsetting to Bloom, and understandably. Yeats here issues a clear tribal call for cultural unity by appealing to racial instinct and historical experience: blood and soil. A Jewish critic, who had never shared in the experience, but rather was steeped in another totally alien, and thus had no real comprehension of the soul-state from which the poet spoke, would, as a matter of course, feel hostile to such verse. Too bad for Bloom and his fellows that Yeats’s reputation is already established; they have now little other to do but to wring their hands and rend their garments in their studies.

William Butler Yeats: rooted in Ireland, a seeker in the Western tradition, a giant of our race and culture; like Nietzsche, a “conqueror of Time”; and, perchance, one of the heralds of the times to come:

O silver trumpets, be you lifted up

And cry to the great race that is to come.

Long-throated swans upon the waves of time,

Sing loudly, for beyond the wall of the world

That race may hear our music and awake.

– “The King’s Threshold”

Notes

[1] Joseph M. Hone, W. B. Yeats, 1865–1939 (1943).

[2] Harold Bloom, Yeats (1972).

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg