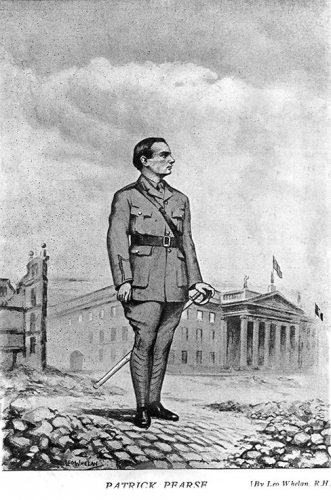

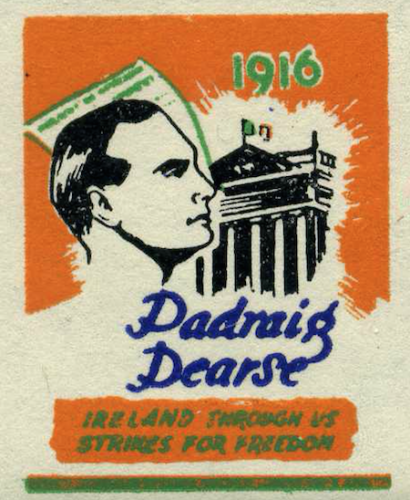

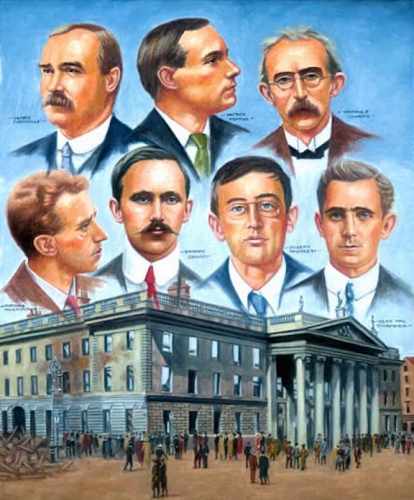

On Easter Monday, April 24, 1916, while all Europe was mobilized for the first of its terrible civil wars, Patrick Pearse, James Connolly, and several hundred “militia men” from the Irish Citizen Army and the Nationalist Volunteers commandeered the General Post Office on Dublin’s O’Connell (then Sackville) Street.

On Easter Monday, April 24, 1916, while all Europe was mobilized for the first of its terrible civil wars, Patrick Pearse, James Connolly, and several hundred “militia men” from the Irish Citizen Army and the Nationalist Volunteers commandeered the General Post Office on Dublin’s O’Connell (then Sackville) Street.

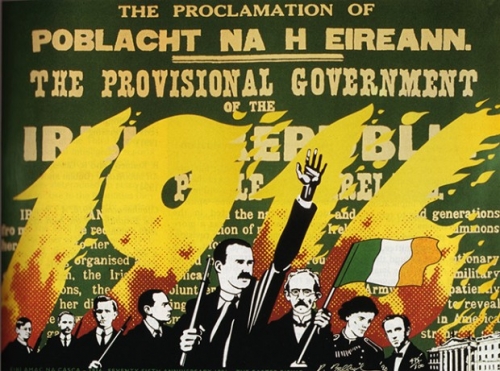

Once a defensive parameter was established around the stately, neo-classical symbol of British rule, the tall, lanky 37-year-old Pearse, titular head of the self-proclaimed “provisional government of the Irish Republic,” appeared on the GPO’s steps to read out to a small crowd of bewildered and skeptical by-standers a proclamation.

“Irishmen and Irishwomen: In the name of God and the dead generations from which she receives her old tradition of nationhood, Ireland, through us, summons her children to her flag and strikes for her freedom.”

This line — the entire proclamation, even — is a work of art.

Some say the Uprising itself was a work of art.

***

As the GPO was being fortified on the 24th, 700 or 800 lightly-armed rebels, most with shotguns and home-made bombs, some with rifles secretly obtained from Germany — (the same “gallant ally in Europe” who allied with the IRA in the next European civil war) — spread out across Dublin, occupying other public buildings and sites associated with the Crown.

The Uprising was not a direct military assault on British authority per se (the rebels lacked the fire power). It was nevertheless an armed assertion of Irish authority — an authority however poorly armed that was nevertheless imbued with a powerful idea — the idea that does not tire or break and that imparts “its mantle of strength upon those in its service” — the idea of destiny (Francis Parker Yockey).

***

The English garrison in Ireland, larger than the garrison that held India, was caught entirely off-guard by the insurrection.

There was good reason for this.

In 1914 the Irish Parliamentary Party had not only pledged to support the British government, as Germany challenged its supremacy on the killing fields of Flanders and Northern France, the party called on its paramilitary wing, the 170,000 strong Irish Volunteers, to enlist in the British army. (The ten to twenty thousand Volunteers who refused to follow the IPP’s lead, those rechristened “the Nationalist Volunteers,” were to be the Uprising’s principal military arm, though their mobilization, for reasons too complicated to explain here, was countermanded at the last moment).

The Irish people, one of the most dispossessed and economically distressful of Europe’s peoples, were enjoying a brief spell of good times, as employment and agriculture flourished in the wake of the British war effort.

Westminster had also promised to implement Home Rule, once the war ended.

Ireland never seemed more securely in English hands.

***

The rebellion was greeted with surprise and rage — by both the British government and the Irish population.

This would change, as the government turned the rebels into martyrs, “snatching political defeat from the jaws of military victory.”

In the view of much of the world, especially among the popular classes of nationalist-minded Irish-America, the forces of the crown were seen as reacting with characteristic English brutality, as their powerful naval guns pounded Britain’s second most important city, destroying the GPO and much of the city’s heart, as well as wounding or killing a thousand civilians

James Connolly, that most Aryan of Marxists, had thought the British forces, beholden to English capital, would never turn their guns on their own commercial property: Little did he know — and little did he realize that his sophisticated understanding of urban warfare would crumble before this fact.

Ground troops, supported by field artillery, then suppressed the lingering rebellion on the streets — though not before Pearse ordered a general surrender, once it was clear civilians were the main victim of Britain’s crushing counter-attack.

***

Like most of the six armed rebellions the Irish had raised in the previous 200 years, there was a good deal of futility and desperation in the Easter Uprising — begun on Monday and extinguished, at least so everyone thought, by the following Saturday.

Pearse, Connolly, and much of the Irish Republican Brotherhood responsible for the insurrection had, in fact, no illusion that they would succeed or even survive the Uprising.

Once rounded up, the fifteen nationalist leaders of the revolt were court martialed and shot.

“Dear, dirty Dublin” came, then, to resemble the war-ravaged towns and cities along the Franco-German front, as the cause of Irish freedom seemed to suffer another damning setback.

Yet five years later, Ireland was a nation once again.

***

Like much of the Uprising’s revolutionary nationalist leadership, Pearse sought a path that led away not just from British rule, but from British modernity — which, like its larger civilizational expression, seemed to suffocate everything heroic and great in life.

Against the empire’s cold mechanical forces, he arrayed the powerful mythic pulse of the ancient Gaels.

As Carl Schmitt might have described it: “Against the mercantilist image of balance there appears another vision, the warlike image of a bloody, definitive, destructive, decisive battle.”

Pearse was not alone in thinking myth superior to matter.

Indeed, his Ireland was Europe in microcosm — the Europe struggling against the forces of the coming anti-Europe.

In Germany, no less than in Ireland, powerful cultural movements based on “peasant” mythology and traditional culture had arisen to repulse the modern world — movements which did much to revive the spirit of Western Civilization (before it was again struck down by the ethnocidal Pax Americana).

In Germany this movement frontally challenged the continental status quo, in Ireland it challenged the British Empire.

Lacking a political alternative, the frustrated national unity of 19th-century “Germany” had looked to increase its cultural cohesion and self-consciousness.

Like its German counterpart, Ireland’s Celtic Twilight was part of a larger European movement — of a romantic and romanticizing nationalism — to revive the ancient Volk culture in its struggle against the anti-national forces of money and modernity.

Though the Famine had delayed the movement’s advent in Ireland, it came.

The cultural phase of Irish nationalism formally began with Parnell’s fall in 1889. Turning away from the personal and political tragedy of their uncrowned king, nationalists started re-thinking their destiny in other than political terms.

If the Germans, in the cultural assertion of their nationalism, had to free themselves from the overwhelming hegemony of French culture, the Irish had to turn away from the English, who considered them barbarians.

In rejected liberal modernity, these barbarians sought to recapture something of the archaic, Aryan spirit still evident in the Táin Bó Cuailnge and in Wagner’s Ring des Nibelingen — the spirit distilled today in Guillaume Faye’s “archeofuturism.”

***

Before Parnell, Irish resistance to English subjugation (with the exception of O’Connell’s movement) had taken the form of numerous, rather badly planned military defeats.

But the Irish had little recourse, especially in law. (Indeed, the only justice for the Irishman in Ireland came from his shillelagh, whenever it took precedent over the judge’s gravel).

Centuries of Irish violence and resistance had convinced the English of Irish lawlessness and of their incapacity for self-rule.

Savage English repression begot savage Irish resistance, which, in turn, begot savage repression and so on: The long, unfortunate, blood-soaked dialectic of Anglo-Irish relations.

The empire’s violence was legitimated in the name of cultural superiority. Throughout British society, which thought itself the height of Western civilization, it was held that Ireland before the Norman Conquest had lacked any form of civilization or High Culture — even the learned David Hume held this view. Indeed, the Irish were seen as yet fully civilized.

In British eyes this “race” was a lesser breed, somewhat like a nonwhite one, like wild Indians, and imperial conflict with it was something like conflict with a savage tribe — it was not the relationship Paris had to her provinces, it was not even what the German Hapsburgs had to their Slavic nations.

The Catholic Irish are famous in 19th-century English periodicals for their simian features.

The lawless Celts (the very word comes from the Greek for “fighter”), so obviously inferior to the civilized “Saxons,” brought upon themselves thus the rent racking, the enclosures, and the garrison state that came with the English occupation (the so-called “Union”).

***

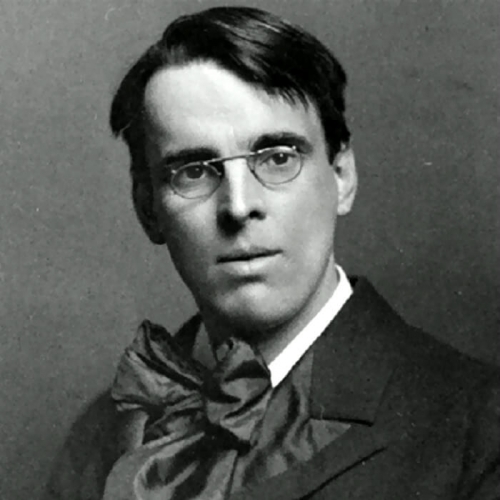

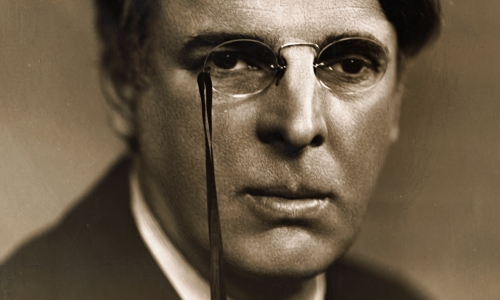

William Butler Yeats, Lady Gregory, John Millington Synge, and other gifted members of the Anglo-Irish Ascendancy had no love for the world’s workshop, longing, as they did, for “the integral community of the old manorial days.”

The Irish Literary Renaissance was launched, following Parnell’s fall, with “The Wanderings of Oisin,” in which Yeats called for “a new literature, a new philosophy, and a new nationalism.”

Irish folklore for Yeats was not simply Irish, but the conservator of “an ancient, sacred worldview overwhelmed by the abstract, highly differentiated,” and generally ignoble forms of modern bourgeois life (forms, as we Americans have learned, that have, among other negative things, imbued money-changing aliens with great power over us).

For Ireland’s cultural nationalists, the past was a realm of meaning — prefiguring a future to rebuke the present. And a great past, which the culturalist nationalists soon enough discovered, beckoned, as William Irwin Thompson surmised, “a future fit for an exalted heritage.”

The romanticized “peasant,” along with the medieval knight and the gentleman cavalier, were celebrated in Yeats’ poetic rebellion against the modern world.

This “nationalization” of the people’s heritage appealed to nationalists disgusted with things English; its moralistic rejection of decadence and empire also appealed to the emerging Irish Catholic lower-middle class; at the highest, most important, level, its mythic vision organically merged with “a culture that renews itself by reference to its mythology.”

By the early 20th century, a new ideology gripped Ireland, Germany, and many European nations, an ideology which defined the nation in racialist, romantic, and anti-modernist terms centered on certain cultural polarities: viz., anti-liberal versus liberal, past v. present, agricultural community v. industrial society, small moral nation v. decadent world empire, myth v. reason, quality v. quantity, Gaelic v. English, German v. French, Ireland v. England, Europeans v. Anglo-Americans, etc.

***

The hard men of the Irish Republican Brotherhood — (the Fenians, the progenitors of the many factions making up today’s IRA, were very unlike the genteel Anglo-Irish artists who made Dublin a cultural capital of the Anglophone world) — but they too were part of the general revolt against liberal civilization — against the devirilizing tenets of positivist thought, against the primacy of monetary values, against the spirit-killing effects of mechanization, massification, and deracination, and, above all, against the empire’s imposition on everything native to Irish identity.

In France, Italy, and Spain rebels opposing liberalism’s realm of “consummate meaninglessness” threw bombs, in Ireland, where the cult of violence was ancient, they made up an army of bomb-throwers — for it was the nation seeking to be born, “ourselves alone,” not the solitary resister, who filled the rebel ranks.

Violence and self-sacrifice, as such, needed no justification in Catholic Ireland (though they seemed totally alien and barbaric to England’s liberal Protestants).

***

Ireland’s brave rebels are best seen against a European backdrop.

At its center was the Sorelian myth of violence, imagining the overthrow of Cromwell’s cursed regime.

This myth of violence was no ideology, but a Nietzschean assertion of will.

Its dreamscape was the apocalyptic catastrophe in which all things became possible.

Its promised violence wasn’t aimless or nihilistic, like that of a Negro hoodlum, but soteriological, seeking the salvation of man’s soul in a world made especially evil by the efficacy of science and reason.

***

Violence here — in the mythic context of Pearse’s imagination and in the social-political world of late 19th-century, early 20th-century Europe — became “a path to a new faith” — a path that ran over the ruins of modernity, as it endeavored to redeem it.

The Irish cosmological view, in Patrick O’Farrell’s study, perceived England as a secular, unethical, money-grubbing power that had “violated” Caithlin Ni Houlihan — the Old Woman of Beare, Roisin Dubb, Shan Van Vocht, Deidre of the Sorrows, Queen Sive, and all the feminine symbols personifying Ireland’s perennial spirit.

In such a cosmology, national liberation was eschatological, millennarian, and, above all, mythic.

For here myth seizes the mind of the faithful as it prepares them to act. Its idea is “apocalyptic, looking toward a future that can come about only through a violent destruction of what already exists.”

Pearse’s myth was of a noble Ireland won by violent, resolute, virile action — nothing less would merit his blood sacrifice.

Fusing the unique synergy of millennarian Catholicism (with its martyrs), ancient pagan myth (with its heroes), and a spirit of redemptive violence (couched in every recess of Irish culture) — his myth has since become the ideological justification for the physical force tradition of Irish republicanism — a tradition which holds that no nation can gain its freedom except through force of arms — that is, by taking it — by forthrightly asserting it in the Heideggerian sense of realizing the truth of its being.

Pearse’s allegiance to armed struggle came with his disgust with parliamentary politics. He thought Parnell’s party “had sat too long at the English table” — that it had come to regard Irish nationality “as a negotiable rather than a spiritual thing.”

All states, he considered, rested on force. If Ireland should be “freed” through Home Rule, that is, under British auspices, it would make the Irish smug and loyal — and British.

With the advent of the Great War of 1914 and the Burgfrieden negotiated between the parliamentary nationalists of the IPP and the British government, the flame of Ireland’s national spirit began to dim.

The violent break with Britain, which Pearse and other revolutionary nationalists sought, was inspired by the conviction that every compromise weakened Ireland’s soul and strength — that the flame had always to burn heroically — that the spirit had to be pure — otherwise the sacramental lustre of the Republican cause would be lost.

***

The tradition of armed resistance of which Pearse became the leading Irish symbol was not unique to Ireland, but part the same European tradition that inspired the Slavic Communist storming of the Winter Palace, the same that guided the anti-liberal, fascist, and national socialist opposition to liberalism’s interwar regimes — the same that appears still on the hard streets of Northern Ireland and in the minds of a small number of exceptional Europeans.

For Pearse, the Uprising was more than a blow struck for Irish freedom, it was “a revolt against the materialistic, rationalistic, and all-too-modern world” of the British Empire.

Pearse was not unlike Charles Péguy, who too conceived of a national myth “to stand against the modernist tide.”

Péguy: “Nothing is as murderous as weakness and cowardice / Nothing is as humane as firmness.”

This was Pearse’s thought, exactly.

***

Such a mythic conviction came, though, at a high cost, for it required a willful self-immolation and the promise of death, however heroic.

***

Pearse’s conviction sprang from Ireland’s long history of resistance and the Aryo-European spirit it reflected, but it also came from the old sagas, from the stories and legends of the ancient Gaels, that celebrated the values and traditions of Ireland’s heroic age.

Prior to the modern age Ireland’s Gaelic vernacular literature was the largest of any European peoples, except that of the Greeks and Romans.

The Irish loved to tell stories, a great many of which their monks wrote down a thousand years ago.

Like other Gaelic-speaking nationalists, Pearse was especially affected by the Ulster Cycle of legends and myths associated with Cù Chulainn — the symbol of Ireland — the symbol of one powerful man standing alone against a terrible, overwhelming force — the Irish Achilles — whose heroic temper was a rebuke to the corruptions and weaknesses of the modern age.

***

In August 1915, a year into the European civil war, and three-quarters of a year before the Easter Uprising, the IRB staged a ceremonial burial for one of its own — in a country where ceremonial burials have often given birth to new forms of life.

In his funeral oration at the grave side of the dead Fenian, O’Donovan Rossa, the Cù Chulainn (who would soon fight his epic battle in the GPO) augured that: “Life springs from death and from the graves of patriot men and women spring nations. . . . They [the English] think that they have pacified Ireland. They think that they have pacified half of us and intimidated the other half. They think that they have provided against everything: but the fools, the fools, the fools! — they have left us our Fenian dead, and while Ireland holds these graves, Ireland unfree shall never be at peace.”

Man, in Pearse’s mythic imagination, doesn’t act on the chance of being successful, but for the sake of doing what needs to be done. The nationalist movement, united in hatred of the English ruling class, was full of such men.

Their doing, their sacrifice — like that of Jesus on the cross or the tragic Cù Chulainn burying his son in the indifferent sea tide — was of utmost importance.

For everything, the rebels knew, would follow from it — the slaughtered sheep brightening the sacramental flame of their spirit.

***

Some historians claim Pearse’s “suicidal” insurrection bequeathed “a sense of moral conviction to revolutionaries all over the world.”

From a military perspective, the Uprising, of course, was a categorical failure. But morally, it became something of a world-changing force — which wasn’t surprising in a country like Ireland, whose mythology had long favored ennobling failures.

As Pearse told the military tribunal that condemned him to death: “We seem to have lost. We have not lost. To refuse to fight would have been to lose. We have kept faith with the past, and handed down a tradition to the future.”

***

In the course of the extraordinary events following The Proclamation (as the rebels kept faith with their past), mind, imagination, and myth fused into a synergetic force of unprecedented brilliance and power — the terrible beauty being born.

***

Patrick Pearse fell before the English guns soon after Easter, but the ennobling image of him standing upright in the burning GPO lives on in the heritage he willed not just to Irishmen but to all white men.

For of the insurgents, at least fifty of them, including Pearse himself, were of mixed Irish-English parentage.

They fought the cruel empire not just for Ireland’s sake, but for the sake of redeeming, in themselves, something of the old Aryo-Gaelic ways.

April 24, 2010

Sources:

Thomas M. Coffey, Agony at Easter: The 1916 Irish Uprising (Baltimore: Penguin, 1971).

Ruth Dudley Edwards, Patrick Pearse: The Triumph of Failure (New York: Taplinger, 1978).

Sean Farrell Moran, Patrick Pearse and the Politics of Redemption (Washington: Catholic University Press of America, 1994).

Joseph O’Brien, Dear, Dirty Dublin: 1899–1916 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982).

Patrick O’Farrell, Ireland’s English Question (New York: Schocken, 1971).

Dáithí Ó hÓgáin, The Lore of Ireland (Cork: Boydell, 2006).

William Irwin Thompson, The Imagination of an Insurrection: Dublin, Easter 1916 (New York: Harper, 1967).

Despite cultural nativism being at its centre, Yeats’s Protestant background was shared by most of the leading figures of the movement. Among these were the Galway based aristocrat and folklorist Lady Gregory, whose Coole Park home formed the nerve centre of the movement, and the Rathfarnham born poet and playwright J.M. Synge, who later found solace in Irish peasant culture on the western seaboard as being a vestige of authentic Irish life amid a society of anglicisation. The poet’s identification with both the people and the very landscape of Ireland over the materialist England arose from his early childhood and formative experiences in Sligo, a period that would define him both as an artist as well as a man.

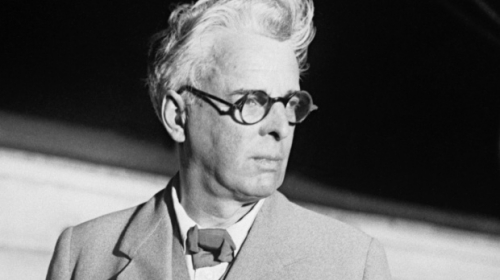

Despite cultural nativism being at its centre, Yeats’s Protestant background was shared by most of the leading figures of the movement. Among these were the Galway based aristocrat and folklorist Lady Gregory, whose Coole Park home formed the nerve centre of the movement, and the Rathfarnham born poet and playwright J.M. Synge, who later found solace in Irish peasant culture on the western seaboard as being a vestige of authentic Irish life amid a society of anglicisation. The poet’s identification with both the people and the very landscape of Ireland over the materialist England arose from his early childhood and formative experiences in Sligo, a period that would define him both as an artist as well as a man. Despite some apprehension about the nature of the Easter Rising, as well as a latent sense of guilt that his work had inspired a good deal of the violence, Yeats took a dignified place within the Irish Seanad. He immediately began to orientate the Free State towards his ideals with efforts made to craft a unique form of symbolism for the new State in the form of currency, the short lived Tailteann Games and provisions made to the arts. Despite his objection to anti-divorce legislation passed by the Free State and his defence of Republican prisoners, the writer Grattan Freyer details how the poet’s primary gripe with the new state was a failure to be sufficiently conservative, to cast off any trappings of liberalism inherited from England, and embrace some sort of aristocratic order (with Yeats no doubt playing a major role). In cabinet, he found minister Kevin O’Higgins (photo) as a potential ally and was so aghast at the young minister’s death at the hands of Republican gunmen that he penned his poem “Blood And The Moon” a defence not only of the ailing world of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy to which he belonged, but also to the poet’s brand of conservative politics.

Despite some apprehension about the nature of the Easter Rising, as well as a latent sense of guilt that his work had inspired a good deal of the violence, Yeats took a dignified place within the Irish Seanad. He immediately began to orientate the Free State towards his ideals with efforts made to craft a unique form of symbolism for the new State in the form of currency, the short lived Tailteann Games and provisions made to the arts. Despite his objection to anti-divorce legislation passed by the Free State and his defence of Republican prisoners, the writer Grattan Freyer details how the poet’s primary gripe with the new state was a failure to be sufficiently conservative, to cast off any trappings of liberalism inherited from England, and embrace some sort of aristocratic order (with Yeats no doubt playing a major role). In cabinet, he found minister Kevin O’Higgins (photo) as a potential ally and was so aghast at the young minister’s death at the hands of Republican gunmen that he penned his poem “Blood And The Moon” a defence not only of the ailing world of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy to which he belonged, but also to the poet’s brand of conservative politics.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

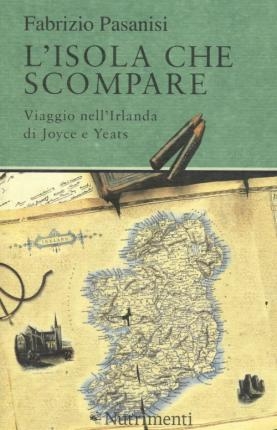

Dans L'isola che scompare (L'île qui disparaît), Fabrizio Pasanisi souligne le lien organique entre l'Irlande et ses chantres. Dans son livre, qui mêle chroniques de voyage et excursions dans l'histoire, Pasanisi exprime un véritable acte d'amour pour la terre des landes vertes, une île "traversée par des histoires, pas moins que l'Italie, des histoires qui viennent de la terre, des histoires qui remplissent l'air", entre une pluie et une autre, des histoires qui naissent de la fantaisie et de la vie - et où d'autre -, et qui restent pour nous, qui allons là-bas, et reconnaissons les lieux, les personnages, dans un visage, entre les rives d'une rivière".

Dans L'isola che scompare (L'île qui disparaît), Fabrizio Pasanisi souligne le lien organique entre l'Irlande et ses chantres. Dans son livre, qui mêle chroniques de voyage et excursions dans l'histoire, Pasanisi exprime un véritable acte d'amour pour la terre des landes vertes, une île "traversée par des histoires, pas moins que l'Italie, des histoires qui viennent de la terre, des histoires qui remplissent l'air", entre une pluie et une autre, des histoires qui naissent de la fantaisie et de la vie - et où d'autre -, et qui restent pour nous, qui allons là-bas, et reconnaissons les lieux, les personnages, dans un visage, entre les rives d'une rivière".

At an early age Yeats became involved in mysticism which would prove controversial his whole life. Kodani explains, “The early poetry of William Butler Yeats was very much bound up with the forces and interests of his early years. Many of these influences — such as that of Maud Gonne, his father, and his own mystic studies — have been elucidated by some careful scholarship.” Yeats’ writing was influenced by his study of mysticism. He joined the Theosophical Society as his immediate family’s tradition was not very religious. Later he “became interested in esoteric philosophy, and in 1890 was initiated into the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn” (Seymour-Smith). He would pursue mystical philosophy the rest of his life to a greater or lesser degree.

At an early age Yeats became involved in mysticism which would prove controversial his whole life. Kodani explains, “The early poetry of William Butler Yeats was very much bound up with the forces and interests of his early years. Many of these influences — such as that of Maud Gonne, his father, and his own mystic studies — have been elucidated by some careful scholarship.” Yeats’ writing was influenced by his study of mysticism. He joined the Theosophical Society as his immediate family’s tradition was not very religious. Later he “became interested in esoteric philosophy, and in 1890 was initiated into the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn” (Seymour-Smith). He would pursue mystical philosophy the rest of his life to a greater or lesser degree.

![william-butler-yeats-by-reemerv[162091].jpg](http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com/media/01/02/2740805010.jpg) The falcon is modern man. The motive force of the falcon’s flight is human desire, pride, spiritedness, and Faustian striving. The spiral structure of the flight is the intelligible measure–the moderation and moralization of human desire and action–imposed by the moral center of our civilization, represented by the falconer, the falcon’s master, our master, which I interpret in Nietzschean terms as the highest values of our culture. The tether that holds us to the center and allows it to impose measure on our flight is the “voice of God,” i.e., the claim of the values of our civilization upon us; the ability of our civilization’s values to move us.

The falcon is modern man. The motive force of the falcon’s flight is human desire, pride, spiritedness, and Faustian striving. The spiral structure of the flight is the intelligible measure–the moderation and moralization of human desire and action–imposed by the moral center of our civilization, represented by the falconer, the falcon’s master, our master, which I interpret in Nietzschean terms as the highest values of our culture. The tether that holds us to the center and allows it to impose measure on our flight is the “voice of God,” i.e., the claim of the values of our civilization upon us; the ability of our civilization’s values to move us.

Cù Chulainn in the GPO:

Cù Chulainn in the GPO: On Easter Monday, April 24, 1916, while all Europe was mobilized for the first of its terrible civil wars, Patrick Pearse, James Connolly, and several hundred “militia men” from the Irish Citizen Army and the Nationalist Volunteers commandeered the General Post Office on Dublin’s O’Connell (then Sackville) Street.

On Easter Monday, April 24, 1916, while all Europe was mobilized for the first of its terrible civil wars, Patrick Pearse, James Connolly, and several hundred “militia men” from the Irish Citizen Army and the Nationalist Volunteers commandeered the General Post Office on Dublin’s O’Connell (then Sackville) Street.

Bruno de Cessole

Ex: http://www.valeursactuelles.com (archives: 2011)