The response of much western commentary to the Russia China agreements has been scepticism that they can ever burgeon into an outright partnership because of the supposedly long history of mutual suspicion and hostility between the two countries. The Economist for example refers to the two countries as “frenemies”. To see whether these claims are actually justified I thought it might be useful to give a short if rather summary account of the history of the relationship between the two countries.

Official contacts between China and Russia began with border clashes in the 1680s which however were settled in 1689 by the Treaty of Nerchinsk, which delineated what was then the common border. At this time Beijing had no political or diplomatic links with any other European state save the Vatican, which was informally represented in Beijing by the Jesuit mission.

The Treaty of Nerchinsk was the first formal treaty between China and any European power. The Treaty of Nerchinsk was basically a pragmatic border arrangement. It was eventually succeeded by the Treaty of Kyakhta of 1727, negotiated on the initiative of the Kangxi Emperor and of Peter the Great, who launched the expedition that negotiated it shortly before before his death.

The Treaty of Kyakhta provided for a further delineation of the common border. It also authorised a small but thriving border trade. Most importantly, it also allowed for the establishment of what was in effect a Russian diplomatic presence in Beijing in the form of an ecclesiastical settlement there. Russia thereby became only the second European state after the Vatican to achieve a presence in Beijing. It did so moreover more than a century before any of the other European powers. Russia was of course the only European power at this time to share a common border with China (a situation to which it has now reverted since the return to China of Hong Kong). It is also notable that the Treaty of Kyakhta happened on the initiative of Peter the Great. Peter the Great’s decision to launch the expedition that ultimately led to the Treaty of Kyakhta shows that even this supposedly most “westernising” of tsars had to take into account Russia’s reality as a Eurasian state.

For the rest of the Eighteenth Century and the first half of the Nineteenth Century relations between the Russian and Chinese courts remained friendly though hardly close. St. Petersburg was the only European capital during this period to host occasional visits by the Chinese Emperor’s representatives. During the British Macartney mission to Beijing of 1793 the senior Manchu official tasked with negotiating with Macartney had obtained his diplomatic experience in St. Petersburg. As a result of these contacts at the time of the Anglo French expedition to Beijing in 1860 Ignatiev, the Russian diplomat who acted as mediator between the Anglo French expedition and the Chinese court, could call on the services of skilled professional interpreters and was in possession of accurate maps of Beijing whilst the British and the French had access to neither. Russian diplomatic contacts with the court in Beijing during this period do not seem to have been afflicted with the protocol difficulties that so complicated China’s relations with the other European powers and which contributed to the failure of the Macartney mission. This serves as an indicator of the pragmatism with which these contacts were conducted.

This period of distant but generally friendly relations ended with the crisis of 1857 to 1860 when Russia used the Chinese court’s preoccupation with the Taiping rebellion and China’s difficult relations with the western Europeans culminating in the Anglo French expedition of 1860 to secure the annexation of the Amur region. The Chinese continue to see the third Convention of Beijing of 1860 which secured the Amur territory for Russia as an “unequal treaty”. They have however accepted its consequences and formally recognised the border (which was properly speaking part of Manchu rather than Chinese territory). At the time it must have been resented. However it is probably fair to say that Russia would have been seen in China as a marginally less dangerous aggressor during this period than the western powers Britain and France (especially Britain) if only because China’s relations with these two countries were much more important.

As the Nineteenth Century wore on relations between Russia and China seem to have improved with Russia, undoubtedly for self-interested reasons, playing an important role in the Three Power Intervention that forced Japan to moderate its demands on China following China’s defeat in the Sino Japanese war of 1895. Russian policy of supporting China and the authority of the Chinese court against the Japanese however fell by the wayside when Russia forced the Chinese court in 1897 to grant Russia a lease of the Chinese naval base of Port Arthur. This was much resented in China and damaged Russia’s image there. Russia also became drawn into the suppression of the anti-foreign 1900 Boxer Rising, an event which destabilised the Manchu dynasty and which led to a short lived Russian occupation of Manchuria to suppress the Boxers there. This is not the place to discuss the diplomacy or the reasons for the conflict which followed which is known as the Russo Japanese war of 1904 to 1905. Suffice to say that the ground war was fought entirely on Chinese territory and ended in stalemate (though with the balance starting to shift in favour of the Russians), that I know of no good English account of the war or of the events that preceded it, that the war was precipitated entirely by a straightforward act of Japanese aggression and that the popular view that the war was preceded and/or provoked by Russian economic and political penetration of Korea or plans to annex Manchuria are now known to have no basis in fact.

A radical improvement in Russian Chinese relations took place following the October 1917 revolution caused by the decision of the new Bolshevik government to renounce the extra territorial privileges Russia had obtained in China as a result of the unequal treaties. The USSR became the strongest supporter during this period of Sun Ya-tsen’s Chinese nationalist republican movement and of the Guomindang government in Nanjing that Sun Ya-tsen eventually set up. Sun Ya-tsen for his part was a staunch friend and supporter of the USSR. Though many are aware of the very close relationship between the USSR and China in the 1950s few in my experience know of the equally strong and arguably more genuine friendship between their two governments in the 1920s.

In the two decades that followed the USSR became China’s strongest international supporter in its war against Japanese aggression, a war which has defined modern China and of which the outside world knows lamentably little. During this period the USSR had to balance its support for China’s official Guomindang led government that was supposedly leading the struggle against the Japanese with its support for the Chinese Communist Party (originally the leftwing of the Guomindang movement) with which the Guomindang was often in armed conflict. The USSR also had to balance its support for China with its need to avoid a war in the east with Japan at a time when it was being threatened in the west by Nazi Germany and its allies. The skill with which the government of the USSR performed this difficult feat has gone almost wholly unrecognised.

Following the defeat of Japan in 1945 the USSR’s military support was (as is now known) crucial though obviously not decisive to the Chinese Communist Party’s victory in the civil war against the Guomindang, which led to the establishment in 1949 of the People’s Republic. A decade of extremely close political, military and economic relations followed during which the two countries were formally allies. As is now known this relationship in reality was always strained and eventually broke down in part because of mutual personal antagonism between the countries’ two leaders, Khrushchev and Mao Zedong, but mainly because of Chinese anger at the USSR’s failure to support a war to recover Taiwan and above all because of China’s refusal as the world’s most populous country and oldest civilisation to accept a subordinate position to the USSR in the international Communist movement. The rupture was made formal by Khrushchev’s decision in 1960 to withdraw from China the Soviet advisers and economic assistance that had been sent there. Supporters of sanctions may care to note that on the two occasions Russia has used sanctions (against Yugoslavia in 1948 and against China in 1960) they backfired spectacularly on Russia resulting in consequences for Russia that were entirely bad.

The Sino Soviet rupture of 1960 resulted in a decade and a half of very strained relations. An attempt to restore relations to normal following Khrushchev’s fall in 1964 was wrecked, possibly intentionally, by the Soviet defence minister Marshal Malinovsky who encouraged members of the Chinese leadership to overthrow Mao Zedong through a coup similar to the one that had overthrown Khrushchev. Relations with the USSR during this period also increasingly became hostage to Chinese internal politics with Mao and his supporters during the period of political terror known as the Cultural Revolution routinely accusing their opponents of being Soviet agents. This period of difficult relations eventually culminated in serious border clashes in 1969, an event that panicked the leadership of both countries and which led each of them to explore alignments against each other with the Americans.

This period of very tense relations basically ended in 1976 with the death of Mao Zedong who shortly before his death is supposed to have issued an injunction to the Chinese Communist party instructing it to restore relations with the USSR. Once the post Mao succession disputes were resolved with the victory of Deng Xiaoping a process of outright rapprochement began the start of which was formally signalled in the USSR by Leonid Brezhnev in a speech in Tashkent in 1982 which he made shortly before his death. By 1989 the process of rapprochement was complete allowing Gorbachev to visit Beijing in the spring of that year when however his visit was overshadowed by the Tiananmen disturbances.

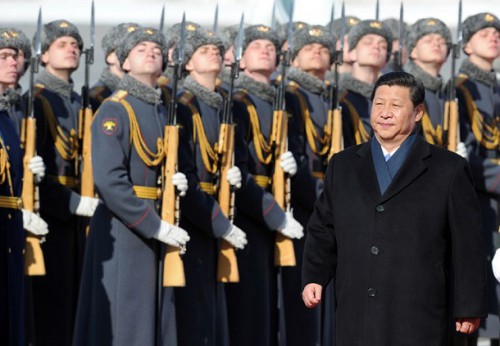

Since then there has been a steady strengthening of relations. Gorbachev refused to involve the USSR in the sanctions the western powers imposed on China following the Tiananmen disturbances. Yeltsin, despite the strong pro-western orientation of his government, remained a firm advocate of good relations with China and worked to build on the breakthrough achieved in the 1980s. In 1997 in a speech in Hong Kong Jiang Zemin already spoke of Russia as China’s key strategic ally. In 1998 the two countries acted for the first time openly in concert on the Security Council to oppose the US bombing of Iraq (“Operation Desert Fox”). Subsequently both countries strongly opposed the US led attacks on Yugoslavia in 1999 and on Iraq in 2003. Since then their cooperation in political, economic and security matters has intensified. Whilst their relations have had their moments of difficulty (eg. over Russian complaints of illicit Chinese copying of weapon systems) and the development of their economic relations has lagged well behind that of their political relations (inevitable given the disastrous state of the Russian economy in the 1990s) it is difficult to see on what basis they can be considered “frenemies”.

The reality is that Russia and China have for obvious reasons of history, culture and above all geography faced through most of their history in different directions: China towards Asia (where it is the supreme east Asian civilisation) and Russia towards Europe. That should not however disguise the fact that their interaction has been very prolonged (since the 1680s), – longer in fact than that of China with any of the major western powers – and generally peaceful and mostly friendly. Periods of outright hostility have been short lived and rare. Despite sharing the world’s longest border all-out war between the two countries has never happened. On the two occasions (in the 1680s and 1960s) when it briefly appeared that it might, both drew back and eventually sought and achieved a compromise. For China Russia’s presence on its northern border has in fact been an unqualified benefit, stabilising and securing the border from which the greatest threats to China’s independence and security have traditionally come.

Western perceptions of the China Russia relationship are in my opinion far too heavily influenced by the very brief period of the Sino Soviet conflict of the 1960s and 1970s. Across the 300 or so years of the history of their mutual interaction the 15 or so years of this conflict represent very much the anomaly not the rule. Given this conflict’s idiosyncratic origins in ideological and status issues that are (to put it mildly) extremely unlikely to recur again, to treat this conflict as representing the norm in China’s and Russia’s relations with each other seems to me frankly farfetched. The past is never a safe guide to the future. However on the basis of the actual history of their relations, to argue that China’s and Russia’s strategic partnership is bound to fail because of their supposed long history of suspicion and conflict towards each other is to argue from prejudice rather than fact.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

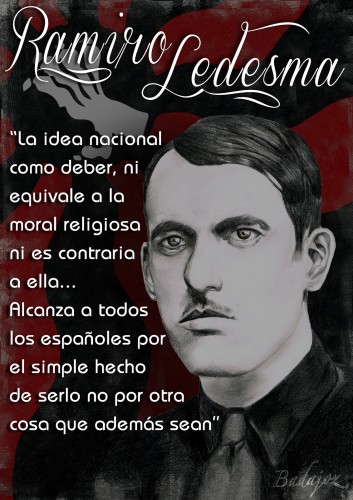

Ledesma fue un doctrinario, pero también un hombre de acción. Era consciente de que meditar sobre las ideas solo es admisible si se tiene el valor de llevarlas a la práctica. Eso implica elegir una estrategia, unas tácticas, unos objetivos políticos, un criterio organizativo y formar una clase política dirigente. Se ha aludido bastante al Ramiro Ledesma doctrinario, pero nada en absoluto al estratega político. Y a partir de 1933 tenía una estrategia muy clara: la formación de un “gran partido fascista español” que agrupara a distintas ramas dispersas hasta entonces y a distintos líderes, necesarios todos ellos para alcanzar la masa crítica suficiente para derrocar a la frustrada república y construir un Estado Nacional Sindicalista. En ese sentido, el camino seguido por Ledesma es la estrategia de construcción del partido sumando distintas fuerzas ya existentes y dispersas hasta ese momento, algunas de las cuales incluso en el mundo anarco-sindicalista. Si Ledesma participó en la experiencia de El Fascio fue precisamente por eso, para favorecer una iniciativa unitaria, y si a última hora lanzó Nuestra Revolución fue para crear un medio “aceptable” para que sectores del anarco-sindicalismo asumieran los mismos ideales por los que estaba trabajando Falange Española.´

Ledesma fue un doctrinario, pero también un hombre de acción. Era consciente de que meditar sobre las ideas solo es admisible si se tiene el valor de llevarlas a la práctica. Eso implica elegir una estrategia, unas tácticas, unos objetivos políticos, un criterio organizativo y formar una clase política dirigente. Se ha aludido bastante al Ramiro Ledesma doctrinario, pero nada en absoluto al estratega político. Y a partir de 1933 tenía una estrategia muy clara: la formación de un “gran partido fascista español” que agrupara a distintas ramas dispersas hasta entonces y a distintos líderes, necesarios todos ellos para alcanzar la masa crítica suficiente para derrocar a la frustrada república y construir un Estado Nacional Sindicalista. En ese sentido, el camino seguido por Ledesma es la estrategia de construcción del partido sumando distintas fuerzas ya existentes y dispersas hasta ese momento, algunas de las cuales incluso en el mundo anarco-sindicalista. Si Ledesma participó en la experiencia de El Fascio fue precisamente por eso, para favorecer una iniciativa unitaria, y si a última hora lanzó Nuestra Revolución fue para crear un medio “aceptable” para que sectores del anarco-sindicalismo asumieran los mismos ideales por los que estaba trabajando Falange Española.´