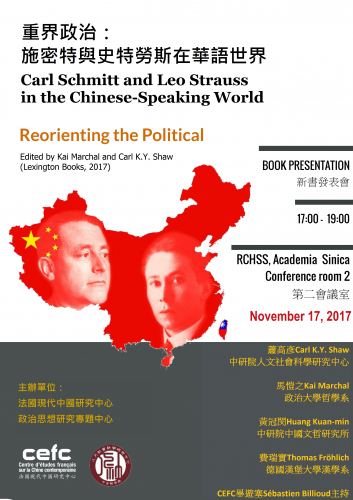

Carl Schmitt and Leo Strauss in the Chinese-Speaking World: Reorienting the Political, Kai Marchal and Carl K.Y. Shaw, eds. Lanham, Lexington Books, 2017.

Carl Schmitt and Leo Strauss are extremely popular in China, especially in Mainland China—this is no longer a secret in the Western academia. As early as 2003, Stanley Rosen had already told the Boston Globe that “A very, very significant circle of Strauss admirers has sprung up, of all places, China.”[1] Then, in 2010, Mark Lilla, after returning from a visit to Chinese universities, published a widely-circulated article in the New Republic, reporting that there was a “strange taste in Western philosophers” among Chinese scholars and college students, i.e. their strange obsession with Leo Strauss and Carl Schmitt.[2] A 2015 article published on “The China Story” website by Flora Sapio further described the reception of Carl Schmitt by China’s New Left intellectuals and showed the author’s concern with the potential danger of Schmitt’s legal and political theory.[3] Schmitt and Strauss have become philosophical and political stars in China is well-known in the Western world. The question that still puzzles people is—Why?

Carl Schmitt and Leo Strauss are extremely popular in China, especially in Mainland China—this is no longer a secret in the Western academia. As early as 2003, Stanley Rosen had already told the Boston Globe that “A very, very significant circle of Strauss admirers has sprung up, of all places, China.”[1] Then, in 2010, Mark Lilla, after returning from a visit to Chinese universities, published a widely-circulated article in the New Republic, reporting that there was a “strange taste in Western philosophers” among Chinese scholars and college students, i.e. their strange obsession with Leo Strauss and Carl Schmitt.[2] A 2015 article published on “The China Story” website by Flora Sapio further described the reception of Carl Schmitt by China’s New Left intellectuals and showed the author’s concern with the potential danger of Schmitt’s legal and political theory.[3] Schmitt and Strauss have become philosophical and political stars in China is well-known in the Western world. The question that still puzzles people is—Why?

It is in line with this growing visibility of China’s “Schmitt-Strauss fever” that Kai Marchal and Carl K.Y. Shaw edited this current volume on Carl Schmitt and Leo Strauss in the Chinese-speaking World, a long-waited contribution to the decoding of and engagement with this enigmatic intellectual phenomenon. The greatest virtue of this volume is, as the two editors say in the Introduction, that “while individual authors may differ in their evaluation of the nature of this reception and its possible implications,” they all agree that this intellectual phenomenon should be treated in a serious way (p. 13). Taken as a whole, this volume is currently the most in-depth discussion in the entire world of the Chinese receptions of Schmitt and Strauss, and should be recommended to anyone who is interested in Chinese intellectual history in the post-Mao era.

Readers who are intrigued by the Schmitt-Strauss fever in the Sinophone world would naturally ask three questions, and they expect that this volume would answer them from different angles. First, why are Schmitt and Strauss so popular in China (the “Why” question)? Second, how do Chinese intellectuals use Schmitt’s and Strauss’s political thought to participate in China’s political debates? And third, how can liberals respond to these Chinese Schmittians and Straussians, if they are using Schmitt’s and Strauss’s “illiberal” thought to express their discontent with the Western modernity? The contributors in this volume aim to do all these jobs, but as I shall demonstrate, several drawbacks of the book might have made it unsuccessful to fulfill readers’ expectations. Specifically, I shall argue, while the volume contains detailed answers to the second question, it does not provide persuasive and sufficient accounts of the “Why” question. In addition, though the volume aims to engage with the Chinese Schmittians and Straussians, the strategies that some contributors use may not be promising in the Chinese context.

As a book dealing with the Chinese reception of Schmitt and Strauss, several chapters are devoted to the analysis of the writings of Chinese Schmittians and Straussians, with a focus on how they use Schmitt’s and Strauss’s ideas to address distinctively Chinese issues. The chapters by Shaw, Marchal and Nadon are especially helpful for readers to know who the Schmittians and Straussians are in China and how they are politically motivated to invoke Schmitt’s and Strauss’s authorities. These close analyses, based on first-hand textual evidence, provide solid bases for the contributors in this volume to engage with the Chinese thinkers, and to show what they are getting right and where they are going wrong.

In terms of the historical accounts of China’s reception of Schmitt and Strauss, contributors have made significant efforts in reconstructing the historical context of China’s post-Mao period and in explaining why certain Schmittian and Straussian ideas have resonance in this particular circumstance. For example, Shaw is very successful in providing “a contextual and immanent analysis which demonstrates the rationale of the receptions, the inner logic of the theoretical reconstructions, and their relevance for contemporary Chinese intellectual debates” (p. 40). Similarly, Charlotte Kroll reconstructs the legal and political issues that Chinese intellectuals cared about when Schmitt was introduced, and connects Schmitt fever with what Jan-Werner Mueller calls “Schmitt’s globalization” in the 1990s. Before unfolding his engagement with and critique of Liu Xiaofeng’s interpretation and application of Strauss’s political thought in the Chinese context, Marchal presents an overview of the intellectual trajectories of China’s leading Straussians and briefly explains why Strauss is attractive to scholars who are concerned with the “nihilism” issue in the post-Maoist China.

However, as the Schmitt-Strauss fever is the most enigmatic, even “strange” intellectual phenomenon in contemporary China, this volume should have devoted more efforts to the investigations into the “Why” question. A reasonable account of this phenomenon must answer 1) why it is in this particular historical moment that Schmitt and Strauss become authoritative for many Chinese intellectuals, and 2) why it is Schmitt and Strauss, not other critics of Western modernity and liberal democracy, that especially attract the attentions of Chinese intellectuals. In the 1980s and 90s, for example, one of the most fashionable things to do among China’s leading intellectuals was to discuss Nietzsche, Heidegger, Sartre, and Foucault. Why these critics of modernity and liberal democracy, either from the Left or the Right, did not trigger a similar wave of anti-liberalism in China is a question that all scholars interested in Chinese political thought should painstakingly think about. Therefore, a contextualized account of the Schmitt-Strauss fever is not complete if there lacks a comprehensive investigation of China’s reception of Western thought in general, and of China’s reception of anti-Enlightenment and illiberal thought in particular. This, I admit, is not an easy task, but is worth doing if we really take the Schmitt-Strauss fever in China seriously.

Another thing that this volume should have done is an excavation of the pre-Schmittian and pre-Straussian writings of intellectuals like Liu Xiaofeng and Gan Yang, to name a few, because these writings may provide some clues for explaining their intellectual transformations. Contributors like Marchal and Nadon have mentioned that Liu and Gan were not Schmittians and Straussians from the very beginning of their academic lives, but what they have not fully elaborated is that these two figures were active liberals before encountering Schmitt and Strauss. In the 1980s and early 90s, Liu was a “cultural Christian” advocating for China’s radical transformation from “traditional culture” to Christianity, but his political position was by and large liberal. Gan asked Confucianism to modernize itself in order to embrace modern values such as individual rights, equality, pluralism, and democracy. Before their encounter with Schmitt and Strauss, they were obsessed by various “illiberal” or “anti-liberal” philosophers in the West, such as Nietzsche, Heidegger and Sartre, but this obsession did not prevent them from appreciating Berlin, Habermas and Rawls. Just one year before Liu Xiaofeng’s open conversion to Strauss’s political thought and his embrace of illiberalism, he was using public reason liberalism to criticize Charles Taylor and his Chinese followers who wanted to use communitarian insights to fight for the Confucian causes.

After his Straussian turn, however, Liu has been increasingly intolerant of liberal political theory, thinking that a return to the “classical mentality” is incompatible with the pursuit of liberal reform in China. A detailed description of Liu’s “liberal years” may make his sudden but whole-hearted conversion to Schmitt and Strauss more enigmatic, but may also provide hints about whether his particular and idiosyncratic conception of liberalism actually paved way for his later conversion to anti-liberalism. For example, a close reading of his early works shows that the pursuit of an “absolute value” is a constant theme in his liberal years, and that his discomfort with value pluralism to some extent foreshadows his embrace of Strauss’s political thought.

The absence of detailed and sound explanations of the Schmitt-Strauss fever may be remedied if the Chinese Schmittians and Straussians in this volume could take this opportunity to explain why they think that China needs Schmitt and Strauss for imagining its political future. Readers may have the expectation to look for direct articulations and defenses of their motivations for invoking the authority of Schmitt and Strauss. The volume contains three articles written by Mainland Chinese and Taiwanese scholars who are sympathetic toward Schmitt and Strauss.

Among them, however, only Chuan-Wei Hu’s is a straightforward defense of Strauss in the Taiwanese context and an articulation of why Strauss matters for Taiwan’s democracy. The other two “Mainland” pieces, surprisingly, refrain from providing any direct answers to the “Why” question, and thus miss the opportunity for Mainland Chinese Schmittians and Straussians to make a case for themselves. Han Liu’s chapter, which argues that the global diffusion of constitutionalism and judicial guardianship is a bad thing, does not provide any positive proposals for China to design an alternative legal system in accordance with Schmittian insights, despite his merely one-paragraph assertion that “China should pay attention to its own political culture, however defined, to ground a firm constitutional authority” (pp. 134-5).

The chapter by Jianhong Chen, a leading Mainland Straussian, provides an excellent reinterpretation of Strauss’s political thought, and he argues, against various Western scholars, that Strauss should not be understood as a conservative thinker merely defending the status quo, because political philosophy as Strauss understands is still a radical “negation” of actual politics, thus preserving a utopian and normative dimension. By claiming that Heinrich Meier’s interpretation of Strauss is a myth (pp. 197-8), Chen hints that Liu Xiaofeng’s reception of Strauss might also be mistaken, because Liu encountered Strauss largely through Meier’s secondary literature. But, again, Chen does not elaborate the possible implications of his understanding of Strauss, such as whether Strauss can be used in a way to challenge the political status quo in China. If readers who are not able to read Chinese want to understand why Schmitt and Strauss are important for China from an indigenous perspective, they can read Wang Tao’s article published in the Claremont Review of Books, in which he provides an explanation and justification of China’s reverence for Strauss.[4]

Lastly, the most significant accomplishment that this volume has achieved is a theoretical engagement with the Chinese Schmittians and Straussians. The contributors believe that this wave of anti-liberalism in China inspired by Schmitt and Strauss should be taken seriously, and this volume is a valuable addition to the intercultural conversation in the burgeoning field of comparative political theory. Chapters written by Shaw, Wenning, Nadon and Marchal are recommended for readers who are looking for evaluations of the Schmitt-Strauss fever. Among these four chapters, Shaw and Marchal are generally critical of the Chinese Straussians, arguing that they either fail to grasp Strauss’s true spirit or distort his key teachings. Wenning has a similar critical attitude toward Chinese Schmittians and claims that these scholars have not recognized the “internal complexity” (p. 82) of Schmitt’s thought. Based on his discussion of Schmitt’s later writings, to which few Schmitt scholars have paid adequate attention, Wenning shows how this underappreciated dimension of Schmitt’s political thought might have the potential to overcome the one-sidedness of the current Chinese reception of Schmitt. In contrast, Nadon provides the most positive evaluation of the Chinese reception of Strauss, and contends that Liu Xiaofeng may ultimately “articulate a new and inspiring vision of what Chinese civilization could be” (p. 12).

A theme that unifies many contributors in this volume is their worry that some leading Chinese intellectuals in this fever, most notably Liu Xiaofeng, have an extremely hostile attitude toward liberalism and liberal democracy. While their discontent with Western cultural hegemony should be sympathized, contributors still feel that liberalism as a universal value should be defended in the Chinese context. As Marchal and Wenning have exemplified, one strategy to criticize Chinese Schmittians and Straussians is to show that they are misinterpreting Strauss and neglecting the internal richness of Schmitt. However, I wonder whether this is a promising strategy for engaging with these anti-liberal scholars.

Take Marchal’s chapter as an example, the underlying logic of his strategy is that if Chinese intellectuals get Strauss correctly, then they should have used Strauss for different purposes, rather than merely justifying China’s particular tradition and extant authoritarian regime. Based on his comparison of Strauss and Liu Xiaofeng, he argues that Liu’s use of Strauss “leads to a number of fundamental distortions” of Strauss’s claims in On Tyranny, that “instead of having discerned Strauss’s esoteric messages, Liu may thus have misunderstood his teacher” (p. 184), and that “Liu Xiaofeng’s project is being played out according to a very different agenda than Strauss’s original project,” which Strauss “likely never anticipated” (p. 181). In a word, “It is quite remarkable that the Chinese Straussian Liu Xiaofeng can relate to Strauss’s critique of liberal democracy without further ado in a non-liberal, non-democratic society (which China undoubtedly still is)” (p. 186).

However, what makes Marchal’s comparison of Strauss and Liu problematic is that he applies a double standard when interpreting Strauss’s and Liu’s works respectively. In terms of Strauss, Marchal is fully aware that his works are notoriously enigmatic, and recognizes that reconstructing a “real Strauss” is extremely difficult, so he carefully chooses what he thinks the “more convincing and theoretically plausible” secondary literature, and based on these, provides a charitable reading of Strauss’s political philosophy, i.e., Strauss as an eternal sceptic and critical friend of liberal democracy. When it comes to Liu, he chooses Liu’s most “Straussian book” to date, Republic and Statecraft, as a target for criticism, because he thinks that Liu misapplies Strauss’s teachings in On Tyranny in this book. However, the problem with his reading of Liu is that he does not attempt to use the same method to decode Strauss’s and Liu’s writings, thus making his understanding of Liu dubious and uncharitable.

As Liu himself claims in the afterword of this book, Republic and Statecraft is an expansion of his reading notes of Xiong Shili’s lengthy letter to Mao Zedong.[5] In this book, there is no place where Liu openly articulates his own positions, and, like Strauss, he hides his own ideas behind his textual analysis of Xiong’s letter. Xiong was a well-known New Confucian philosopher in twentieth century China who claimed that modern values such as equality and democracy could be interpreted from the Confucian canons. When the CCP came to power in 1949, Xiong decided to stay in the Mainland, and wrote a series of letters to Mao to make a plea for the protection of China’s traditional culture by arguing that the revolutionary spirit was compatible with Confucianism. In one letter, Xiong expressed his admiration of Mao by claiming that Mao was a modern reincarnation of the ancient sage-king, and that his authoritarian rule was necessary for China to realize freedom and democracy. Liu finds this letter extremely interesting, and uses a Straussian hermeneutics to interpret Xiong’s thought.

Marchal is aware that Liu is practicing Straussian hermeneutics in this book, but surprisingly, he unreflectively presumes that Liu affirms and praises Xiong’s ideas. Without presenting any quotations from this book, Marchal argues that “[Liu’s] argumentation in Republic and Statecraft strongly suggests that Liu regards Xiong Shili’s attempt to ground Mao’s revolution in the horizon of traditional Chinese culture as meaningful” (p. 188). It is true that Liu does admire Mao in recent years, but this does not necessarily mean that Liu expresses his admiration in a way similar to Xiong’s. His other Straussian writings show his disapproval of the attempt in the twentieth century to develop modern values from within the Confucian tradition, because the Straussian teaching of “transcending the modern horizon” inspires him to praise classical Confucianism, in which, according to him, moral and political hierarchy is the core of the authentic Confucian spirit. As Xiong belongs to the New Confucian school and speaks highly of equality and democracy, it is highly probable that Liu, in his Republic and Statecraft, fundamentally disagrees with Xiong’s ideas. Therefore, while reading Strauss in a charitable way, Marchal to a large degree provides an uncharitable reading of Liu. This double standard fatally discredits his claim that Liu distorts Strauss’s thought, as Liu may easily retort that Marchal is distorting Liu’s thought in the first place.

However, even if Marchal could distribute his charity evenly to Strauss and Liu, the effectiveness of his strategy in combating Chinese anti-liberalism is still doubtful. After all, to what extent is Liu distorting Strauss is a highly contestable issue, as Strauss himself is an extremely enigmatic political thinker. For Marchal, the “real Strauss” he identifies is a Strauss constantly skeptical about Western modernity but never attempts to offer any positive account of a radical alternative, not to mention actively pursues such an alternative in political actions (p. 176). In contrast, Liu distorts Strauss in the sense that he wants to craft a concrete alternative based on the Chinese tradition, and tends to put this project into action.

Were Marchal to do a close analysis of Liu’s interpretations of Strauss, he would quickly find that Liu is almost familiar with Strauss’s entire corpus, and it is extremely difficult to claim that Liu distorts Strauss without going through all his quotations of Strauss’s original texts. In particular, what Marchal does not mention in this chapter is that Liu is especially interested in Strauss’s “theologico-political predicament,” i.e., the tension between the philosopher and the political society. According to Strauss, it is the philosopher’s virtue to constrain its eagerness to challenge the conventions, customs, moral codes, religions, superstitions, laws, and political authorities of the political society, because a replacement of these nomoi with pure reason will lead to the very disintegration of the political society. Therefore, the philosopher should uphold and gently improve the nomoi in his exoteric teachings, while conceal his true philosophical teachings in his esoteric writings.

What Liu takes from Strauss is that a philosopher in the Chinese context should do the same thing, but this leads him to protect the extant values and political authority which Chinese people have inherited from the ancient times, against the encroachment of Enlightenment thought from the modern West. Liu’s construction of the Chinese nomoi might be wrong and politically motivated, as Marchal shows in his chapter, but this does not mean that Liu’s understanding of Strauss per se is also mistaken. After all, Strauss never anticipated that his thought would be applied someday in a non-Western society, so he did not set a rule for approvable applications, despite his criticism of totalitarianism and communism. Therefore, instead of “distorting” Strauss, one might say that Liu is “extending” Strauss in the Chinese context.

Therefore, if Marchal really wants to criticize Chinese Straussianism and defend liberal principles, his call for a correct understanding and application of Strauss in Mainland China may not work well. Even if there is a correct understanding of Strauss, the application of Strauss might be “beyond right and wrong,” and Marchal actually accepts that “[Strauss’s] writings encourage alternative readings in the context of non-Western intellectual traditions” (p. 174). In the “Conclusion” of his chapter, Marchal hopes that “it may be possible that other forms of Chinese Straussianism may preserve a genuinely critical, zetetic force,” a “more balanced understanding of the cultural differences between East and West,” and a less nationalist defense of the authoritarian regime (p. 191).

However, if Marchal really wants to achieve these goals and give liberalism a try in China, one may wonder whether Strauss is the “Mr Right”—Why not drop Strauss and resort to other liberal thinkers in the West for intellectual resources? After all, as primarily a critic of modernity and liberal democracy, Strauss not only upsets liberals in China but also liberals in the Western world. His mystical genre and his unwillingness to engage in public dialogues make him unfit for defending liberalism, let alone defending liberalism in the Chinese context. As the prospect of liberalism in China has been increasingly bleak in recent years, the need for a straightforward defense of basic liberal principles is needed. Building a liberal-friendly team of Straussianism in China as Marchal hopes is not impossible if some scholars can do what American Straussians did after 2001, i.e., defending Strauss while reconciling him with liberal democracy, but people caring about the future of Chinese liberalism may wonder whether Strauss is really an indispensable intellectual authority at all. After all, why should liberals play the game whose rules are one-sidedly settled by their rivals, instead of opening a new field to play?

Finally, at the end of my review, I should point out that even if the volume offers a variety of insights, it should have had some stylistic improvements for readers to have a better reading experience. Key arguments should be presented clearly in the beginning of each chapter, and convoluted expressions should be avoided. Therefore, readers interested in the Chinese reception of Schmitt and Strauss can start from this volume, but they have good reasons to wait for better works on this subject to be done.

Notes

[1] Jeet Heer, “The Philosopher the Late Leo Strauss has Emerged as the Thinker of the Moment in Washington, but His Ideas Remain Mysterious. Was He an Ardent Opponent of Tyranny, or an Apologist for the Abuse of Power?” Boston Globe, May 11, 2003.

[2] Mark Lilla, “Reading Strauss in Beijing,” New Republic, 2010, http://www.newrepublic.com/article/magazine/79747/reading-leo-strauss-in-beijing-china-marx#, accessed March 19, 2014.

[3] Flora Sapio, “Carl Schmitt in China,” The China Story, Oct 7, 2015, https://www.thechinastory.org/2015/10/carl-schmitt-in-china/, accessed March 31, 2018.

[4] Wang Tao, “Leo Strauss in China,” Claremont Review of Books, Spring 2012, accessed March 19, 2014, http://www.claremont.org/publications/crb/id.1955/article_detail.asp.

[5] Liu Xiaofeng, Gonghe yu jinglun 共和与经纶 (Republic and Statecraft), Beijing, Sanlian chubanshe, 2012, 303-4.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Vous insistez beaucoup, pour l’efficacité de l’action métapolitique, sur la compréhension d’un contexte fait de l’emboîtement de trois éléments : l’Occident, le Système et le Régime. En quelques mots, que voulez-vous dire par là ?

Vous insistez beaucoup, pour l’efficacité de l’action métapolitique, sur la compréhension d’un contexte fait de l’emboîtement de trois éléments : l’Occident, le Système et le Régime. En quelques mots, que voulez-vous dire par là ?