This short piece continues series on some “Deeply Momentous Things” — that is, American intervention in the First World War. (See Part One.) As the first installment has shown in a general way, the background of the war among Europe and its extensions (Canada, Australia, etc.) is crucial to understanding how the United States would eventually declare war on the Central Powers. More specifics on this issue will help us understand just what the might of the United States meant to the warring powers.

European leaders on both sides hoped to change the dynamic of the war in January 1917. Certainly, from a technical military standpoint, 1916 represented a highly complicated and progressive experimentation with methods of war that would break up the stalemate. In answer to a question posed in the first installment — who was winning at the end of 1916 — if I had to choose the side that had the upper hand in December 1916, I would probably choose the Central Powers by a nose.

In December 1916, Field Marshal Haig, Commander of the British forces on the Western Front, sent in an extensive report to his government on the just completed Somme Campaign. The Somme battles had advanced the Allied line in some places but had never come close to a breakthrough. And the losses of both British and French units were appalling. Yet Haig declared the Somme campaign a victory in that it had achieved the wearing down of the Germans and the stabilization of the front.

Yet even with Haig’s report in hand, British statesmen and diplomats were not as optimistic. The Field Marshal’s optimism could not hide the fact that the Somme advance had been at best shallow, and that the Germans still held onto nearly as much of France as they had before. And significantly, the Central Powers were killing Entente troops at a faster rate than the Allies were killing the Germans and their Allies. For every two deaths on the side of the Central Powers, three Entente soldiers were dying.

And there were more concrete signs of distress. In East Central Europe, recently acquired Entente partner Romania faced an Austro-Hungarian, German, and Bulgarian force which had besieged and captured the Romanian capital, Bucharest. The great Brusilov Offensive against the German and Austro-Hungarian armies was an enormous success at its beginning, and almost certainly took pressure off the French defenders at Verdun, in France. But the offensive tailed off with counterattacks that were costly and worrisome. And there were in addition, the enormous losses to the Brusilov fighters, upwards of a million dead, wounded, and captured. In Russia, rumblings of demoralization — including the plot which would end in Rasputin’s murder in December 1916 — emerged as hunger and depletion accompanied deep winter. In retrospect, the Brusilov Offensive planted the seeds of Russia’s revolutionary collapse the following year — which would no doubt have tipped the balanced sharply in favor of the Central Powers had the United States not intervened.

Elsewhere, it is true, things were going somewhat better for the Russians and the British in fighting the Ottoman Empire by December 1916 and January 1917, but many British leaders thought they were looking at the real crisis of the war a hundred years ago. Hoping to bring every kind of weapon to bear in the midst of this depressing and murderous year, British leaders departed from their slogan of “business as usual” in a variety of ways. Great Britain had already adopted conscription a year earlier in January 1916, though not quite in time to supply replacements for the inevitable losses in the coming offensive operations on the Somme and elsewhere. On the diplomatic front, it was in 1916 that the British government began a process that would end by promising overlapping parts of the Ottoman Empire both to the future “king of the Arabs” and to Jews across the world as a future homeland. At the same time, British propaganda designed to influence the United States to enter the war heightened dramatically. Charles Masterman’s War Propaganda Bureau in London worked on the “American question” with newspaper subventions in the United States, speaking tours, increased distribution of the famous Bryce Report on German atrocities in Belgium, and in other ways.

One crucial example of non-traditional attempts to break the impasse was the starvation of German civilians resulting from the British Blockade. In place since late 1914, the Blockade kept even neutrals from delivering food and other essentials to Germany. Before the Blockade was lifted in 1919, somewhere between 500,000 and 800,000 German civilians would die from starvation and from the effects of nutritional shortages on other conditions. Adding indirect deaths influenced by nutritional privation adds many more to the total (see the excellent analysis of the Blockade by David A. Janicki, as well as Ralph Raico’s detailed review of the classic book on the subject by C. Paul Vincent).

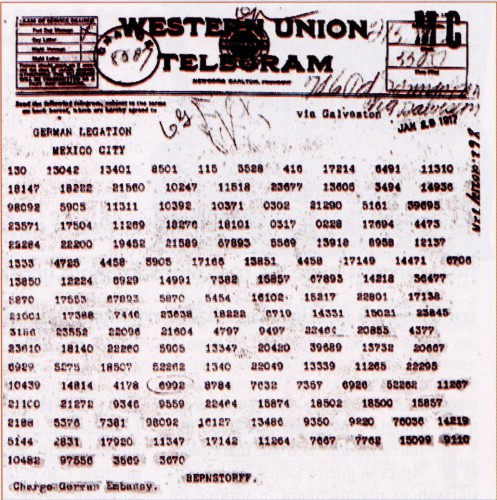

The dynamics of the Blockade intensified among the belligerents the importance of future American decisions. In order to survive the war, Britain had to control the seas. In order to survive the war, Germany had to eat. But at the same time, Germany had to avoid bringing the world’s most powerful economy into the conflict. Unlimited submarine warfare was the most likely way to break the Blockade and eat. But German statesman expressly feared that this step would bring the United States into the war. (See the minutes of a top-level German meeting on the issue of unlimited submarine warfare from August 1916.)

Meanwhile, the one obvious solution to the war — namely, ending it — seemed out of the question. Both sides desired any help they could get, but both sides had turned down offers of mediation, truce, and negotiations, all of these attempts foundering on the acquisitive territorial aims and financial obligations of one belligerent or the other.

One important note: the weather impacted home and battle fronts. The winter of 1916/17 was one of the coldest in memory. The impact on the hungry German home front was immense — this was the terrible “turnip winter,” so-called because turnips were about the only home-grown food available to many. But the soldiers on all sides found the cold almost unbearable as well, misery in the trenches and encampments did not bode well for the future will to fight in any army.

Quite clearly, momentous American decisions were crucial to the future course of the war.

Note: The views expressed on Mises.org are not necessarily those of the Mises Institute.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg