Eurasism is an ideological and social-political current born within the environment of the first wave of Russian emigration, united by the concept of Russian culture as a non-European phenomenon, presenting–among the varied world cultures–an original combination of western and eastern features; as a consequence, the Russian culture belongs to both East and West, and at the same time cannot be reduced either to the former or to the latter.

The founders of eurasism:

- N. S. Trubetskoy (1890–1938)–philologist and linguist.

- P. N. Savitsky (1895–1965)–geographer, economist.

- G. V. Florovsky (1893–1979)–historian of culture, theologian and patriot.

- G. V. Vernadsky (1877–1973)–historian and geopolitician.

- N. N. Alekseev – jurist and politologist.

- V. N. Ilin – historian of culture, literary scholar and theologian.

Eurasism’s main value consisted in ideas born out of the depth of the tradition of Russian history and statehood. Eurasism looked at the Russian culture not as to a simple component of the European civilization, as to an original civilization, summarizing the experience not only of the West as also–to the same extent–of the East. The Russian people, in this perspective, must not be placed neither among the European nor among the Asian peoples; it belongs to a fully original Eurasian ethnic community. Such originality of the Russian culture and statehood (showing at the same time European and Asian features) also defines the peculiar historical path of Russia, her national-state program, not coinciding with the Western-European tradition.

Foundations

Civilization concept

The Roman-German civilization has worked out its own system of principles and values, and promoted it to the rank of universal system. This Roman-German system has been imposed on the other peoples and cultures by force and ruse. The Western spiritual and material colonization of the rest of mankind is a negative phenomenon. Each people and culture has its own intrinsic right to evolve according to its own logic. Russia is an original civilization. She is called not only to counter the West, fully safeguarding its own road, but also to stand at the vanguard of the other peoples and countries on Earth defending their own freedom as civilizations.

Criticism of the Roman-German civilization

The Western civilization built its own system on the basis of the secularisation of Western Christianity (Catholicism and Protestantism), bringing to the fore such values like individualism, egoism, competition, technical progress, consumption, economic exploitation. The Roman-German civilization founds its right to globality not upon spiritual greatness, as upon rough material force. Even the spirituality and strength of the other peoples are evaluated only on the basis of its own image of the supremacy of rationalism and technical progress.

The space factor

There are no universal patterns of development. The plurality of landscapes on Earth produces a plurality of cultures, each one having its own cycles, internal criteria and logics. Geographical space has a huge (sometimes decisive) influence on peoples’ culture and national history. Every people, as long as it develops within some given geographical environment, elaborates its own national, ethical, juridical, linguistic, ritual, economic and political forms. The “place” where any people or state “development” happens predetermines to a great extent the path and sense of this “development”–up to the point when the two elements became one. It is impossible to separate history from spatial conditions, and the analysis of civilizations must proceed not only along the temporal axis (“before,” “after,” “development” or “non-development,” and so on) as also along the spatial axis (“east,” “west,” “steppe,” “mountains,” and so on). No single state or region has the right to pretend to be the standard for all the rest. Every people has its own pattern of development, its own “times,” its own “rationality,” and deserves to be understood and evaluated according to its own internal criteria.

The climate of Europe, the small extension of its spaces, the influence of its landscapes generated the peculiarity of the European civilization, where the influences of the wood (northern Europe) and of the coast (Mediterraneum) prevail. Different landscapes generated different kinds of civilizations: the boundless steppes generated the nomad empires (from the Scythians to the Turks), the loess lands the Chinese one, the mountain islands the Japanese one, the union of steppe and woods the Russian-Eurasian one. The mark of landscape lives in the whole history of each one of these civilizations, and cannot be either separated form them or suppressed.

State and nation

The first Russian slavophiles in the 19th century (Khomyakov, Aksakov, Kirevsky) insisted upon the uniqueness and originality of the Russian (Slav, Orthodox) civilization. This must be defended, preserved and strengthened against the West, on the one hand, and against liberal modernism (which also proceeds from the West), on the other. The slavophiles proclaimed the value of tradition, the greatness of the ancient times, the love for the Russian past, and warned against the inevitable dangers of progress and about the extraneousness of Russia to many aspects of the Western pattern.

From this school the eurasists inherited the positions of the latest slavophiles and further developed their theses in the sense of a positive evaluation of the Eastern influences.

The Muscovite Empire represents the highest development of the Russian statehood. The national idea achieves a new status; after Moscow’s refusal to recognize the Florentine Unia (arrest and proscription of the metropolitan Isidore) and the rapid decay, the Tsargrad Rus’ inherits the flag of the Orthodox empire.

Political platform

Wealth and prosperity, a strong state and an efficient economy, a powerful army and the development of production must be the instruments for the achievement of high ideals. The sense of the state and of the nation can be conferred only through the existence of a “leading idea.” That political regime, which supposes the establishment of a “leading idea” as a supreme value, was called by the eurasists as “ideocracy”–from the Greek “idea” and “kratos,” power. Russia is always thought of as the Sacred Rus’, as a power [derzhava] fulfilling its own peculiar historical mission. The eurasist world-view must also be the national idea of the forthcoming Russia, its “leading idea.”

The eurasist choice

Russia-Eurasia, being the expression of a steppe and woods empire of continental dimensions, requires her own pattern of leadership. This means, first of all, the ethics of collective responsibility, disinterest, reciprocal help, ascetism, will and tenaciousness. Only such qualities can allow keeping under control the wide and scarcely populated lands of the steppe-woodland Eurasian zone. The ruling class of Eurasia was formed on the basis of collectivism, asceticism, warlike virtue and rigid hierarchy.

Western democracy was formed in the particular conditions of ancient Athens and through the centuries-old history of insular England. Such democracy mirrors the peculiar features of the “local European development.” Such democracy does not represent a universal standard. Imitating the rules of the European “liberal-democracy” is senseless, impossible and dangerous for Russia-Eurasia. The participation of the Russian people to the political rule must be defined by a different term: “demotia,” from the Greek “demos,” people. Such participation does not reject hierarchy and must not be formalized into party-parliamentary structures. “Demotia” supposes a system of land council, district governments or national governments (in the case of peoples of small dimensions). It is developed on the basis of social self-government, of the “peasant” world. An example of “demotia” is the elective nature of church hierarchies on behalf of the parishioners in the Muscovite Rus’.

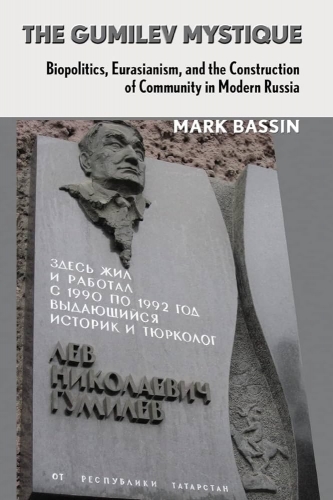

The work of L. N. Gumilev as a development of the eurasist thinking

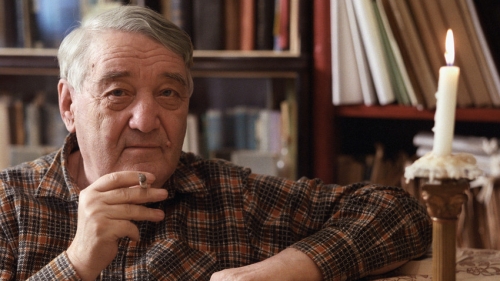

Lev Nikolaevic Gumilev (1912–1992), son of the Russian poet N. Gumilev and of the poetess A. Akhmatova, was an ethnographer, historian and philosopher. He was profoundly influenced by the book of the Kalmuck eurasist E. Khara-Vadan “Gengis-Khan as an army leader” and by the works of Savitsky. In its own works Gumilev developed the fundamental eurasist theses. Towards the end of his life he used to call himself “the last of the eurasists.”

Basic elements of Gumilev’s theory

- The theory of passionarity [passionarnost’] as a development of the eurasist idealism;

- The essence of which, in his own view, lays in the fact that every ethnos, as a natural formation, is subject to the influence of some “energetic drives,” born out of the cosmos and causing the “passionarity effect,” that is an extreme activity and intensity of life. In such conditions the ethnos undergoes a “genetic mutation,” which leads to the birth of the “passionaries”–individuals of a special temper and talent. And those become the creators of new ethnoi, cultures, and states;

- Drawing the scientific attention upon the proto-history of the “nomad empires” of the East and the discovery of the colossal ethnic and cultural heritage of the autochthone ancient Asian peoples, which was wholly passed to the great culture of the ancient epoch, but afterwards fell into oblivion (Huns, Turks, Mongols, and so on);

- The development of a turkophile attitude in the theory of “ethnic complementarity.”

An ethnos is in general any set of individuals, any “collective”: people, population, nation, tribe, family clan, based on a common historical destiny. “Our Great-Russian ancestors–wrote Gumilev–in the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries easily and rather quickly mixed with the Volga, Don and Obi Tatars and with the Buriates, who assimilated the Russian culture. The same Great-Russian easily mixed with the Yakuts, absorbing their identity and gradually coming into friendly contact with Kazakhs and Kalmucks. Through marriage links they pacifically coexisted with the Mongols in Central Asia, as the Mongols themselves and the Turks between the 14th and 16th centuries were fused with the Russians in Central Russia.” Therefore the history of the Muscovite Rus’ cannot be understood without the framework of the ethnic contacts between Russians and Tatars and the history of the Eurasian continent.

An ethnos is in general any set of individuals, any “collective”: people, population, nation, tribe, family clan, based on a common historical destiny. “Our Great-Russian ancestors–wrote Gumilev–in the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries easily and rather quickly mixed with the Volga, Don and Obi Tatars and with the Buriates, who assimilated the Russian culture. The same Great-Russian easily mixed with the Yakuts, absorbing their identity and gradually coming into friendly contact with Kazakhs and Kalmucks. Through marriage links they pacifically coexisted with the Mongols in Central Asia, as the Mongols themselves and the Turks between the 14th and 16th centuries were fused with the Russians in Central Russia.” Therefore the history of the Muscovite Rus’ cannot be understood without the framework of the ethnic contacts between Russians and Tatars and the history of the Eurasian continent.

The advent of neo-eurasism: historical and social context

The crisis of the Soviet paradigm

In the mid-1980s the Soviet society began to lose its connection and ability to adequately reflect upon the external environment and itself. The Soviet models of self-understanding were showing their cracks. The society had lost its sense of orientation. Everybody felt the need for change, yet this was but a confused feeling, as no-one could tell the way the change would come from. In that time a rather unconvincing divide began to form: “forces of progress” and “forces of reaction,” “reformers” and “conservators of the past,” “partisans of reforms” and “enemies of reforms.”

Infatuation for the western models

In that situation the term “reform” became in itself a synonym of “liberal-democracy.” A hasty conclusion was inferred, from the objective fact of the crisis of the Soviet system, about the superiority of the western model and the necessity to copy it. At the theoretical level this was all but self-evident, since the “ideological map” offers a sharply more diversified system of choices than the primitive dualism: socialism vs. capitalism, Warsaw Pact vs. NATO. Yet it was just that primitive logic that prevailed: the “partisans of reform” became the unconditional apologists of the West, whose structure and logic they were ready to assimilate, while the “enemies of reform” proved to be the inertial preservers of the late Soviet system, whose structure and logic they grasped less and less. In such condition of lack of balance, the reformers/pro-westerners had on their side a potential of energy, novelty, expectations of change, creative drive, perspectives, while the “reactionaries” had nothing left but inertness, immobilism, the appeal to the customary and already-known. In just this psychological and aesthetic garb, liberal-democratic policy prevailed in the Russia of the 1990s, although nobody had been allowed to make a clear and conscious choice.

The collapse of the state unity

The result of “reforms” was the collapse of the Soviet state unity and the beginning of the fall of Russia as the heir of the USSR. The destruction of the Soviet system and “rationality” was not accompanied by the creation of a new system and a new rationality in conformity to national and historical conditions. There gradually prevailed a peculiar attitude toward Russia and her national history: the past, present and future of Russia began to be seen from the point of view of the West, to be evaluated as something stranger, transcending, alien (“this country” was the “reformers’” typical expression). That was not the Russian view of the West, as the Western view of Russia. No wonder that in such condition the adoption of the western schemes even in the “reformers’” theory was invoked not in order to create and strengthen the structure of the national state unity, but in order to destroy its remains. The destruction of the state was not a casual outcome of the “reforms”; as a matter of fact, it was among their strategic aims.

The birth of an anti-western (anti-liberal) opposition in the post-Soviet environment

In the course of the “reforms” and their “deepening,” the inadequacy of the simple reaction began to be clear to everyone. In that period (1989–90) began the formation of a “national-patriotic opposition,” in which there was the confluence of part of the “Soviet conservatives” (ready to a minimal level of reflection), groups of “reformers” disappointed with “reforms” or “having become conscious of their anti-state direction,” and groups of representatives of the patriotic movements, which had already formed during the perestroika and tried to shape the sentiment of “state power” [derzhava] in a non-communist (orthodox-monarchic, nationalist, etc.) context. With a severe delay, and despite the complete absence of external strategic, intellectual and material support, the conceptual model of post-Soviet patriotism began to vaguely take shape.

Neo-eurasism

Neo-eurasism arose in this framework as an ideological and political phenomenon, gradually turning into one of the main directions of the post-Soviet Russian patriotic self-consciousness.

Stages of development of the neo-eurasist ideology

1st stage (1985–90)

- Dugin’s seminars and lectures to various groups of the new-born conservative-patriotic movement. Criticism of the Soviet paradigm as lacking the spiritual and national qualitative element.

- In 1989 first publications on the review Sovetskaya literatura [Soviet Literature]. Dugin’s books are issued in Italy (Continente Russia [Continent Russia], 1989) and in Spain (Rusia Misterio de Eurasia [Russia, Mystery of Eurasia], 1990).

- In 1990 issue of René Guénon’s Crisis of the Modern World with comments by Dugin, and of Dugin’s Puti Absoljuta [The Paths of the Absolute], with the exposition of the foundations of the traditionalist philosophy.

In these years eurasism shows “right-wing conservative” features, close to historical traditionalism, with orthodox-monarchic, “ethnic-pochevennik” [i.e., linked to the ideas of soil and land] elements, sharply critical of “Left-wing” ideologies.

2nd stage (1991–93)

- Begins the revision of anti-communism, typical of the first stage of neo-eurasism. Revaluation of the Soviet period in the spirit of “national-bolshevism” and “Left-wing eurasism.”

- Journey to Moscow of the main representatives of the “New Right” (Alain de Benoist, Robert Steuckers, Carlo Terracciano, Marco Battarra, Claudio Mutti and others).

- Eurasism becomes popular among the patriotic opposition and the intellectuals. On the basis of terminological affinity, A. Sakharov already speaks about Eurasia, though only in a strictly geographic–instead of political and geopolitical–sense (and without ever making use of eurasism in itself, like he was before a convinced atlantist); a group of “democrats” tries to start a project of “democratic eurasism” (G. Popov, S. Stankevic, L. Ponomarev).

- O. Lobov, O. Soskovets, S. Baburin also speak about their own eurasism.

- In 1992–93 is issued the first number of Elements: Eurasist Review. Lectures on geopolitics and the foundations of eurasism in high schools and universities. Many translations, articles, seminars.

3rd stage (1994–98): theoretical development of the neo-eurasist orthodoxy

- Issue of Dugin’s main works Misterii Evrazii [Mysteries of Eurasia] (1996), Konspirologija [Conspirology] (1994), Osnovy Geopolitiki [Foundations of geopolitics] (1996), Konservativnaja revoljutsija [The conservative revolution] (1994), Tampliery proletariata [Knight Templars of the Proletariat] (1997). Works of Trubetskoy, Vernadsky, Alekseev and Savitsky are issued by “Agraf” editions (1995–98).

- Creation of the “Arctogaia” web-site (1996) – www.arctogaia.com [2].

- Direct and indirect references to eurasism appear in the programs of the KPFR (Communist Party], LDPR [Liberal-Democratic Party], NDR [New Democratic Russia] (that is left, right, and centre). Growing number of publications on eurasist themes. Issue of many eurasist digests.

- Criticism of eurasism from Russian nationalists, religious fundamentalists and orthodox communists, and also from the liberals.

- Manifestations of an academic “weak” version of eurasism (Prof. A. S. Panarin, V. Ya. Paschenko, F.Girenok and others) – with elements of the illuminist paradigm, denied by the eurasist orthodoxy – then evolving towards more radically anti-western, anti-liberal and anti-gobalist positions.

- Inauguration of a university dedicated to L. Gumilev in Astan [Kazakhstan].

4th stage (1998–2001)

- Gradual de-identification of neo-eurasism vis-à-vis the collateral political-cultural and party manifestations; turning to the autonomous direction (“Arctogaia,” “New University,” “Irruption” [Vtorzhenie]) outside the opposition and the extreme Left and Right-wing movements.

- Apology of staroobrjadchestvo [Old Rite].

- Shift to centrist political positions, supporting Primakov as the new premier. Dugin becomes the adviser to the Duma speaker G. N. Seleznev.

- Issue of the eurasist booklet Nash put’ [Our Path] (1998).

- Issue of Evraziikoe Vtorzhenie [Eurasist Irruption] as a supplement to Zavtra. Growing distance from the opposition and shift closer to the government’s positions.

- Theoretical researches, elaborations, issue of “The Russian Thing” [Russkaja vesch’] (2001), publications in Nezavisimaja Gazeta, Moskovskij Novosti, radio broadcasts about “Finis Mundi” on Radio 101, radio broadcasts on geopolitical subjects and neo-eurasism on Radio “Svobodnaja Rossija” (1998–2000).

5th stage (2001–2002)

- Foundation of the Pan-Russian Political Social Movement EURASIA on “radical centre” positions; declaration of full support to the President of the Russian Federation V. V. Putin (April 21, 2001).

- The leader of the Centre of Spiritual Management of the Russian Muslims, sheik-ul-islam Talgat Tadjuddin, adheres to EURASIA.

- Issue of the periodical Evraziizkoe obozrenie [Eurasist Review].

- Appearance of Jewish neo-eurasism (A. Eskin, A. Shmulevic, V. Bukarsky).

- Creation of the web-site of the Movement EURASIA: www.eurasia.com.ru [3]

- Conference on “Islamic Threat or Threat to Islam?.” Intervention by H. A. Noukhaev, Chechen theorist of “Islamic eurasism” (“Vedeno or Washington?,” Moscow, 2001].

- Issue of books by E. Khara-Davan and Ya. Bromberg (2002).

- Process of transformation of the Movement EURASIA into a party (2002).

Basic philosophical positions of neo-eurasism

At the theoretical level neo-eurasism consists of the revival of the classic principles of the movement in a qualitatively new historical phase, and of the transformation of such principles into the foundations of an ideological and political program and a world-view. The heritage of the classic eurasists was accepted as the fundamental world-view for the ideal (political) struggle in the post-Soviet period, as the spiritual-political platform of “total patriotism.”

At the theoretical level neo-eurasism consists of the revival of the classic principles of the movement in a qualitatively new historical phase, and of the transformation of such principles into the foundations of an ideological and political program and a world-view. The heritage of the classic eurasists was accepted as the fundamental world-view for the ideal (political) struggle in the post-Soviet period, as the spiritual-political platform of “total patriotism.”

The neo-eurasists took over the basic positions of classical eurasism, chose them as a platform, as starting points, as the main theoretical bases and foundations for the future development and practical use. In the theoretical field, neo-eurasists consciously developed the main principles of classical eurasism taking into account the wide philosophical, cultural and political framework of the ideas of the 20th century.

Each one of the main positions of the classical eurasists (see the chapter on the “Foundations of classical eurasism”) revived its own conceptual development.

Civilization concept

Criticism of the western bourgeois society from “Left-wing” (social) positions was superimposed to the criticism of the same society from “Right-wing” (civilizational) positions. The eurasist idea about “rejecting the West” is reinforced by the rich weaponry of the “criticism of the West” by the same representatives of the West who disagree with the logic of its development (at least in the last centuries). The eurasist came only gradually, since the end of the 1980s to the mid-1990s, to this idea of the fusion of the most different (and often politically contradictory) concepts denying the “normative” character of the Western civilization.

The “criticism of the Roman-German civilization” was thoroughly stressed, being based on the prioritary analysis of the Anglo-Saxon world, of the US. According to the spirit of the German Conservative Revolution and of the European “New Right,” the “Western world” was differentiated into an Atlantic component (the US and England) and into a continental European component (properly speaking, a Roman-German component). Continental Europe is seen here as a neutral phenomenon, liable to be integrated–on some given conditions–in the eurasist project.

The spatial factor

Neo-eurasism is moved by the idea of the complete revision of the history of philosophy according to spatial positions. Here we find its trait-d’union in the most varied models of the cyclical vision of history, from Danilevsky to Spengler, from Toynbee to Gumilev.

Such a principle finds its most pregnant expression in traditionalist philosophy, which denies the ideas of evolution and progress and founds this denial upon detailed metaphysical calculations. Hence the traditional theory of “cosmic cycles,” of the “multiple states of Being,” of “sacred geography,” and so on. The basic principles of the theory of cycles are illustrated in detail by the works of Guénon (and his followers G. Georgel, T. Burckhardt, M. Eliade, H. Corbin). A full rehabilitation has been given to the concept of “traditional society,” either knowing no history at all, or realizing it according to the rites and myths of the “eternal return.” The history of Russia is seen not simply as one of the many local developments, but as the vanguard of the spatial system (East) opposed to the “temporal” one (West).

State and nation

Dialectics of national history

It is led up to its final, “dogmatical” formulation, including the historiosophic paradigm of “national-bolshevism” (N. Ustryalov) and its interpretation (M. Agursky). The pattern is as follows:

- The Kiev period as the announcement of the forthcoming national mission (IX-XIII centuries);

- Mongolian-Tatar invasion as a scud against the levelling European trends, the geopolitical and administrative push of the Horde is handed over to the Russians, division of the Russians between western and eastern Russians, differentiation among cultural kinds, formation of the Great-Russians on the basis of the “eastern Russians” under the Horde’s control (13th–15th centuries);

- The Muscovite Empire as the climax of the national-religious mission of Rus’ (Third Rome) (15th–end of the 17th century);

- Roman-German yoke (Romanov), collapse of national unity, separation between a pro-western elite and the national mass (end of the 17th-beginning of the 20th century);

- Soviet period, revenge of the national mass, period of the “Soviet messianism,” re-establishment of the basic parameters of the main muscovite line (20th century);

- Phase of troubles, that must end with a new eurasist push (beginning of the 21st century).

Political platform

Neo-eurasism owns the methodology of Vilfrido Pareto’s school, moves within the logic of the rehabilitation of “organic hierarchy,” gathers some Nietzschean motives, develops the doctrine of the “ontology of power,” of the Christian Orthodox concept of power as “kat’echon.” The idea of “elite” completes the constructions of the European traditionalists, authors of researches about the system of castes in the ancient society and of their ontology and sociology (R. Guénon, J. Evola, G. Dumézil, L. Dumont). Gumilev’s theory of “passionarity” lies at the roots of the concept of “new eurasist elite.”

The thesis of “demotia” is the continuation of the political theories of the “organic democracy” from J.-J. Rousseau to C. Schmitt, J. Freund, A. de Benoist and A. Mueller van der Bruck. Definition of the eurasist concept of “democracy” (“demotia”) as the “participation of the people to its own destiny.”

The thesis of “ideocracy” gives a foundation to the call to the ideas of “conservative revolution” and “third way,” in the light of the experience of Soviet, Israeli and Islamic ideocracies, analyses the reason of their historical failure. The critical reflection upon the qualitative content of the 20th century ideocracy brings to the consequent criticism of the Soviet period (supremacy of quantitative concepts and secular theories, disproportionate weight of the classist conception).

The following elements contribute to the development of the ideas of the classical eurasists:

The philosophy of traditionalism (Guénon, Evola, Burckhardt, Corbin), the idea of the radical decay of the “modern world,” profound teaching of the Tradition. The global concept of “modern world” (negative category) as the antithesis of the “world of Tradition” (positive category) gives the criticism of the Western civilization a basic metaphysic character, defining the eschatological, critical, fatal content of the fundamental (intellectual, technological, political and economic) processes having their origin in the West. The intuitions of the Russian conservatives, from the slavophiles to the classical eurasists, are completed by a fundamental theoretical base. (see A. Dugin, Absoljutnaja Rodina [The Absolute Homeland], Moscow 1999; Konets Sveta [The End of the World], Moscow 1997; Julius Evola et le conservatisme russe, Rome 1997).

The investigation on the origins of sacredness (M. Eliade, C. G. Jung, C. Levi-Strauss), the representations of the archaic consciousness as the paradigmatic complex manifestation laying at the roots of culture. The reduction of the many-sided human thinking, of culture, to ancient psychic layers, where fragments of archaic initiatic rites, myths, originary sacral complexes are concentrated. Interpretation of the content of rational culture through the system of the ancient, pre-rational beliefs (A. Dugin, “The evolution of the paradigmatic foundations of science” [Evoljutsija paradigmal’nyh osnovanij nauki], Moscow 2002).

The search for the symbolic paradigms of the space-time matrix, which lays at the roots of rites, languages and symbols (H. Wirth, paleo-epigraphic investigations). This attempt to give a foundation to the linguistic (Svityc-Illic), epigraphic (runology), mythological, folkloric, ritual and different monuments allows to rebuild an original map of the “sacred concept of the world” common to all the ancient Eurasian peoples, the existence of common roots (see A. Dugin Giperborejskaja Teorija [Hyperborean Theory], Moscow 1993.

A reassessment of the development of geopolitical ideas in the West (Mackinder, Haushofer, Lohhausen, Spykman, Brzeszinski, Thiriart and others). Since Mackinder’s epoch, geopolitical science has sharply evolved. The role of geopolitical constants in 20th century history appeared so clear as to make geopolitics an autonomous discipline. Within the geopolitical framework, the concept itself of “eurasism” and “Eurasia” acquired a new, wider meaning.

From some time onwards, eurasism, in a geopolitical sense, began to indicate the continental configuration of a strategic (existing or potential) bloc, created around Russia or its enlarged base, and as an antagonist (either actively or passively) to the strategic initiatives of the opposed geopolitical pole–“Atlantism,” at the head of which at the mid-20th century the US came to replace England.

The philosophy and the political idea of the Russian classics of eurasism in this situation have been considered as the most consequent and powerful expression (fulfilment) of eurasism in its strategic and geopolitical meaning. Thanks to the development of geopolitical investigations (A. Dugin, Osnovye geopolitiki [Foundations of geopolitics], Moscow 1997) neo-eurasism becomes a methodologically evolved phenomenon. Especially remarkable is the meaning of the Land – Sea pair (according to Carl Schmitt), the projection of this pair upon a plurality of phenomena – from the history of religions to economics.

The search for a global alternative to globalism, as an ultra-modern phenomenon, summarizing everything that is evaluated by eurasism (and neo-eurasism) as negative. Eurasism in a wider meaning becomes the conceptual platform of anti-globalism, or of the alternative globalism. “Eurasism” gathers all contemporary trends denying globalism any objective (let alone positive) content; it offers the anti-globalist intuition a new character of doctrinal generalization.

The assimilation of the social criticism of the “New Left” into a “conservative right-wing interpretation” (reflection upon the heritage of M. Foucault, G. Deleuze, A. Artaud, G. Debord). Assimilation of the critical thinking of the opponents of the bourgeois western system from the positions of anarchism, neo-marxism and so on. This conceptual pole represents a new stage of development of the “Left-wing” (national-bolshevik) tendencies existing also among the first eurasists (Suvchinskij, Karsavin, Efron), and also a method for the mutual understanding with the “left” wing of anti-globalism.

“Third way” economics, “autarchy of the great spaces.” Application of heterodox economic models to the post-Soviet Russian reality. Application of F. List’s theory of the “custom unions.” Actualization of the theories of S. Gesell. F. Schumpeter, F. Leroux, new eurasist reading of Keynes.

Source: Ab Aeterno, no. 3, June 2010.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Lev Nikolayevich Gumilev nació el 1 de octubre de 1912 y falleció el 15 de junio de 1992. Su padre fue el poeta acmeísta Nikolai Stepanovich Gumilev y su madre fue Anna Andreiévna Ajmátova. El padre de Lev, Nikolai Stepanovich, era militar de profesión y, como llevamos dicho, poeta; sus posiciones políticas eran monárquicas. Al regresar a Rusia, tras el triunfo de la revolución, Nikolai Gumilev no disimuló el disgusto que le inspiraba el comunismo con todos sus oportunistas, ahora dueños de la situación en el régimen soviético. Fue capturado por la Cheka y ejecutado por los bolcheviques que lo culparon de estar involucrado en el complot monárquico llamado "la conspiración de Tagantsev", ni siquiera las gestiones de Máximo Gorki -que valoraba al joven poeta- pudieron impedir la sentencia inexorable y en 1921 caía frente a un pelotón de fusilamiento. Anna, la esposa del militar caído en desgracia, pudo salvar la vida, pero ser esposa de un "conspirador" y escribir una poesía intimista le valieron la estigmatización. El hijo del matrimonio, Lev, creció al cuidado de una de sus abuelas y cuando fue mayor conoció en propia carne el gulag. Trece años cumplidos en las minas de níquel de Norilsk y otros campos de concentración, sin que haber servido a la Unión Soviética en la toma de Berlín le hubiera servido para mucho.

Lev Nikolayevich Gumilev nació el 1 de octubre de 1912 y falleció el 15 de junio de 1992. Su padre fue el poeta acmeísta Nikolai Stepanovich Gumilev y su madre fue Anna Andreiévna Ajmátova. El padre de Lev, Nikolai Stepanovich, era militar de profesión y, como llevamos dicho, poeta; sus posiciones políticas eran monárquicas. Al regresar a Rusia, tras el triunfo de la revolución, Nikolai Gumilev no disimuló el disgusto que le inspiraba el comunismo con todos sus oportunistas, ahora dueños de la situación en el régimen soviético. Fue capturado por la Cheka y ejecutado por los bolcheviques que lo culparon de estar involucrado en el complot monárquico llamado "la conspiración de Tagantsev", ni siquiera las gestiones de Máximo Gorki -que valoraba al joven poeta- pudieron impedir la sentencia inexorable y en 1921 caía frente a un pelotón de fusilamiento. Anna, la esposa del militar caído en desgracia, pudo salvar la vida, pero ser esposa de un "conspirador" y escribir una poesía intimista le valieron la estigmatización. El hijo del matrimonio, Lev, creció al cuidado de una de sus abuelas y cuando fue mayor conoció en propia carne el gulag. Trece años cumplidos en las minas de níquel de Norilsk y otros campos de concentración, sin que haber servido a la Unión Soviética en la toma de Berlín le hubiera servido para mucho.

An ethnos is in general any set of individuals, any “collective”: people, population, nation, tribe, family clan, based on a common historical destiny. “Our Great-Russian ancestors–wrote Gumilev–in the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries easily and rather quickly mixed with the Volga, Don and Obi Tatars and with the Buriates, who assimilated the Russian culture. The same Great-Russian easily mixed with the Yakuts, absorbing their identity and gradually coming into friendly contact with Kazakhs and Kalmucks. Through marriage links they pacifically coexisted with the Mongols in Central Asia, as the Mongols themselves and the Turks between the 14th and 16th centuries were fused with the Russians in Central Russia.” Therefore the history of the Muscovite Rus’ cannot be understood without the framework of the ethnic contacts between Russians and Tatars and the history of the Eurasian continent.

An ethnos is in general any set of individuals, any “collective”: people, population, nation, tribe, family clan, based on a common historical destiny. “Our Great-Russian ancestors–wrote Gumilev–in the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries easily and rather quickly mixed with the Volga, Don and Obi Tatars and with the Buriates, who assimilated the Russian culture. The same Great-Russian easily mixed with the Yakuts, absorbing their identity and gradually coming into friendly contact with Kazakhs and Kalmucks. Through marriage links they pacifically coexisted with the Mongols in Central Asia, as the Mongols themselves and the Turks between the 14th and 16th centuries were fused with the Russians in Central Russia.” Therefore the history of the Muscovite Rus’ cannot be understood without the framework of the ethnic contacts between Russians and Tatars and the history of the Eurasian continent. At the theoretical level neo-eurasism consists of the revival of the classic principles of the movement in a qualitatively new historical phase, and of the transformation of such principles into the foundations of an ideological and political program and a world-view. The heritage of the classic eurasists was accepted as the fundamental world-view for the ideal (political) struggle in the post-Soviet period, as the spiritual-political platform of “total patriotism.”

At the theoretical level neo-eurasism consists of the revival of the classic principles of the movement in a qualitatively new historical phase, and of the transformation of such principles into the foundations of an ideological and political program and a world-view. The heritage of the classic eurasists was accepted as the fundamental world-view for the ideal (political) struggle in the post-Soviet period, as the spiritual-political platform of “total patriotism.”