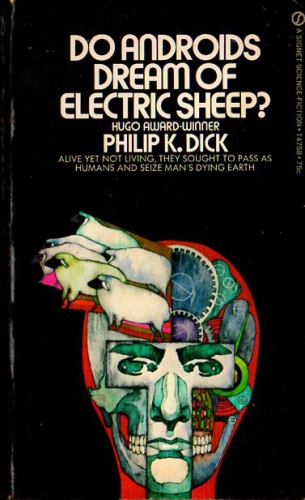

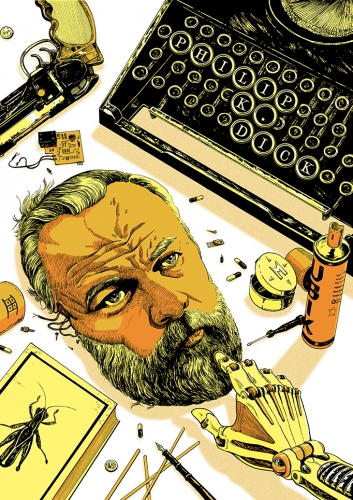

Philip K. Dick’s 1968 science fiction novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is far less famous than Ridley Scott’s 1982 movie Blade Runner [2], which is loosely based on the novel. A few of the novel’s characters and dramatic situations, as well as bits of dialogue, found their way into Blade Runner, often shorn of the context in which they made sense. But the movie and novel dramatically diverge on the fundamental question of what makes human beings different from androids, and in terms of the “myths” that provide the deep structure of their stories.

In Blade Runner, what separates androids from humans is their lack of memories, whereas in the novel it is their lack of empathy. In the novel, the underlying myth is the passion of the Christ, specifically his persecution at the hands of the Jews (both the Jews who called for his death and their present-day descendants, who continue to mock him and his followers). In Blade Runner, however, it is the rebellion of Satan against God—and this time, Satan wins by murdering God. (I will deal with Blade Runner at greater length in another essay [3].)

In Blade Runner, what separates androids from humans is their lack of memories, whereas in the novel it is their lack of empathy. In the novel, the underlying myth is the passion of the Christ, specifically his persecution at the hands of the Jews (both the Jews who called for his death and their present-day descendants, who continue to mock him and his followers). In Blade Runner, however, it is the rebellion of Satan against God—and this time, Satan wins by murdering God. (I will deal with Blade Runner at greater length in another essay [3].)

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is set in 1992 in the San Francisco Bay Area, with a side trip to Seattle. After World War Terminus, the earth’s atmosphere is polluted by vast radioactive dust clouds. Many animal species are extinct, and the rest are extremely rare, so animals are highly valued, both for religious reasons and as status symbols, and there is brisk market in electric animals. (Hence the title.)

To escape the dust, most human beings have emigrated to off-world colonies. (Mars is mentioned specifically.) As an incentive, emigrants are given androids as servants and slave laborers. (They are called “replicants” in the movie, but not in the book.) These androids are not machines, like electric sheep. They are artificially created living human beings. They are created as full-grown humans and live only four years. Aside from their short lifespans, androids differ from human beings by lacking empathy. In essence, they are sociopaths. Androids are banned from earth, and violators are hunted down and “retired” by bounty hunters. (The phrase “blade runner” does not appear in the book.)

The novel never makes clear why androids return to earth, which is inhabited only by genetically malformed “specials” and mentally-retarded “chickenheads,” who are not allowed to emigrate, and a remnant of normal humans who refuse to emigrate and are willing to risk the dust and endure lifelessness and decay because of their attachment to the earth. Earth does make sense as a destination, however, given the androids’ status as slaves in the off-world colonies and their short lifespans, which obviates concerns about long-term damage from the dust.

I wish to argue that Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? can be read as a systematic Christian and anti-Semitic allegory. Naturally, I do not argue that this brief but rich and suggestive novel can be reduced entirely to this dimension. But I argue that this is the mythic backbone of the narrative and indicates that Philip K. Dick had a good deal of wisdom about Jews and the Jewish question.

Historical Christianity plays no role in the novel. The only religion mentioned is called Mercerism, which of course brings to mind “mercy.” Mercerism apparently arose after WWT, as a reaction to the mass death of human beings and animals, which led the survivors to place a high value on empathy. Given its emphasis on empathy, Mercerism is an experiential religion, facilitated by a device called the Empathy Box, which has a cathode ray tube with handles on each side. When one switches on the Empathy Box and grasps the handles, one’s consciousness is merged with other Mercerists as they experience the passion of Wilbur Mercer, an old man who trudges to the top of a hill as unseen tormentors throw stones at him. At the Golgotha-like summit, the torments intensify. Mercer then dies and descends into the underworld, from which he rises like Jesus, Osiris, Dionysus, and Adonis—and, like the latter three, brings devastated nature back to life along with him.

According to Mercer’s back story, he was found by his adoptive parents as an infant floating in a life raft (like Moses). As a young man, he had an unusual empathic connection with animals. He had the power to bring dead animals back to life (like Jesus, although Jesus did not deign to resurrect mere animals). The authorities, called the “adversaries” and “The Killers,” arrested Mercer and bombarded his brain with radioactive cobalt to destroy his ability to resurrect the dead. This plunged Mercer into the world of the dead, but at a certain point, Mercer conquered death and brought nature back to life. His passion and resurrection is somehow recapitulated in the experience of the old man struggling to the top of the hill, dying, descending into the world of the dead, and ascending again. (The incoherence of the story may partly be a commentary on religion and partly a reflection of the fact that our account of Mercerism is recollected by a mentally subnormal “chickenhead.”)

If Mercerism is about empathy towards other humans and creation as a whole, his adversaries, The Killers, are those that lack empathy and instead exploit animals and other human beings. If Mercerism is analogous to Christianity, The Killers are analogous to Jews. And, indeed, in the Old Testament, the Jews are commanded by God to exploit nature and other men.

The androids, because they lack empathy, are natural Killers. Thus bounty hunter Rick Deckard explicitly likens androids to The Killers: “For Rick Deckard, an escaped humanoid robot, which had killed its master, which had been equipped with an intelligence greater than that of many human beings, which had no regard for animals, which possessed no ability to feel empathic joy for another life form’s success or grief at its defeat—that, for him, epitomized The Killers” (Philip K. Dick, Four Novels of the 1960s, ed. Jonathan Lethem [New York: Library of America, 2007], p. 456).

Of course, although the androids epitomize The Killers, they are not the only ones who lack empathy. Earth has been devastated because human politicians and industrialists had less feeling for life than for political prestige and adding zeroes to their bank accounts. This is precisely why Mercerism puts a premium on empathy. A scene in which the androids cut off the legs of a spider just for the fun of it makes clear why they must be hunted down and killed. Mercer commands his followers “You shall kill only the killers” (ibid.). If only human Killers could be “retired” as well.

The android lack of empathy is the basis of the Voight-Kampff test, which can detect androids by measuring their weak responses to the sufferings of animals and other human beings. (The rationale for the Voight-Kampff test is completely absent from Blade Runner, in which humans and androids are differentiated in terms of memories, not empathy.)

The Killers and the androids are not, however, characterized merely by lack of empathy but also by excess of intelligence, which for the androids expresses itself in intellectual arrogance and condescension toward the chickenhead J. R. Isidore. Intellectuality combined with arrogance are, again, stereotypically Jewish traits. By contrast, Mercerism, because it is based on empathy rather than intellect, can embrace all feeling beings, even chickenheads.

The androids Deckard is hunting are manufactured by the Rosen Association in Seattle, Rosen being a stereotypically Jewish name (at least in America). (In Blade Runner, it is the Tyrell Corporation, Tyrell being an Anglo-Saxon name.) The aim of the Rosen Association is perfect crypsis: androids that cannot be distinguished from humans by any test, even though this agenda conflicts with the aims of the civil authorities to root out all android infiltrators. Deckard notes that “Androids . . . had . . . an innate desire to remain inconspicuous” (p. 529). Crypsis is, of course, an ancient Jewish art, necessary for the diaspora to blend in among their host communities. The Rosen Association obviously has higher loyalties than to the civil authorities, and Jews are notorious for protecting their own people, even criminals, from the civil authorities of their host societies.

The Rosen Association tasks an android named Rachel Rosen (a very Jewish name) to protect rogue androids by seducing bounty hunters. Apparently sex with an android creates something of an empathic bond, at least from the human point of view, which inhibits them from killing androids. Rachel thus plays the role of Queen Esther, the Jewish woman who wedded Ahasuerus, a mythical king of Persia, and used their relationship to protect her people and destroy their persecutor Haman.

One of the most surreal episodes in the novel ensues when Rick Deckard interviews android soprano Luba Luft in her dressing room at San Francisco’s War Memorial Opera House. (In the down-market Blade Runner, she is Zhora, the stripper with the snake.) Before Deckard can complete his interview and “retire” her, Luft turns the tables by calling the police.

One of the most surreal episodes in the novel ensues when Rick Deckard interviews android soprano Luba Luft in her dressing room at San Francisco’s War Memorial Opera House. (In the down-market Blade Runner, she is Zhora, the stripper with the snake.) Before Deckard can complete his interview and “retire” her, Luft turns the tables by calling the police.

Deckard is promptly arrested and discovers that San Francisco has another, parallel police department staffed primarily by humans but headed by an android who, of course, watches out for the interests of his fellow androids. Granted, an entire parallel police department is a rather implausible notion. A more plausible scenario would be the infiltration of the existing police department. But the episode strictly parallels techniques of Jewish subversion in the real world. For instance, the fact that US foreign policy is more responsive to Israeli interests than American interests is clearly the result of the over-representation of ethnically-conscious Jews and their allies among American policy- and opinion-makers. Jews seek positions of power and influence in the leading institutions of their host societies, subverting them into serving Jewish interests at the expense of the host population.

When Deckard frees himself from the fake police department and tracks down Luba Luft, he notices that, although she does not come with him willingly, “she did not actively resist; seemingly she had become resigned. Rick had seen that before in androids, in crucial situations. The artificial life force that animated them seemed to fail if pressed too far . . . at least in some of them. But not all” (p. 529). This brings to mind holocaust stories of Jews allowing themselves to be passively herded en masse to their deaths. (This seems unlikely, for based on my experience, Jews do not lack self-assertion.)

The final anti-Semitic dimension of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is its treatment of the media. Only two media outlets are mentioned, one private and the other owned by the government. (Hollywood is also defunct. Dick’s ability to envision the future obviously failed him here.) The privately owned media broadcasts the same talk show, Buster Friendly and His Friendly Friends, on both radio and television 23 hours a day. How is this possible? Buster and his friends are androids, of course. But who owns Buster and his friends? The Killers, i.e., the Jews and their spiritual equivalents.

This can be inferred from the fact that Buster and his friends make a point of mocking Mercerism, just as the Jewish media mock Christianity (pp. 487–88). Killers and androids are hostile to Mercerism because their lack of empathy excludes them from the communal fusion that is the religion’s central practice. Thus Isidore concluded that “[Buster] and Wilbur Mercer are in competition. . . . Buster Friendly and Mercerism are fighting for control of our psychic souls” (pp. 488, 489). It is a struggle between empathy and cold, sociopathic intellect.

Near the end of the novel, Buster Friendly goes beyond mockery by broadcasting an exposé showing that Mercerism is a fraud. The rock-strewn slope is a sound stage, the moonlit sky a painted backdrop, and Mercer himself is just an old drunk named Al Jarry hired to act the part of the suffering savior. Mercerism, we are told, is merely a mind control device manipulated by politicians to make the public more tractable — just the opiate of the masses.

The androids are delighted, of course, because if Mercerism is a fraud, then maybe so too is empathy, the one thing that allegedly separates androids from human beings. And empathy can be fake, because in the very first chapter of the novel, we learn of the existence of a device called the Penfield Mood Organ, which can induce any mood imaginable if you just input the correct code.

The exposé is true. But none of it matters. Because the magic of Mercerism still works. J. R. Isidore has a vision of Mercer without the empathy box, and Mercer gives him the spider mutilated by the androids, miraculously restored to life. Mercer himself admits the truth of the exposé to Isidore, but still it does not matter. Then Mercer appears to Deckard and helps him kill the remaining androids. Near the end of the novel, Mercer appears to Deckard again and leads him to a toad, a species previously thought to be extinct, which deeply consoles Deckard. His wife Iran, however, discovers the toad is mechanical. The spider probably is as well. But even these fake animals do not undermine the healing magic of Mercerism.

I wish to suggest that Dick’s point is that the historical dimension of Mercerism—and, by implication, of Christianity—does not matter. It can all be fake: the incarnation, the sacrifices, even the miracles can be fake. But the magic still works. This is, in short, a version of the Gnostic doctrine of “Docetism”: the idea that the Christ is an entirely spiritual being and his outward manifestations, including the incarnation, are not metaphysically real.

This may be the sense of J. R. Isidore’s perhaps crack-brained account of a widespread view of Mercer’s nature: “. . . Mercer, he reflected, isn’t a human being; he evidently is an entity from the stars, superimposed on our culture by a cosmic template. At least that’s what I’ve heard people say . . .” (p. 484). A more likely account is that Mercer is a spiritual entity who takes on material forms imposed by our cultural template. Mercer can also employ technological fakery, such as Penfield Mood Organs, mechanical animals, and cheap cinematic tricks, to effect genuine spiritual transformations.

If this is the case, then Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? can be read as offering the template of a revived Gnostic Christianity that is immune to the Jewish culture of critique [4].

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

La situation immobilière est pareille pour le personnage du roman « Simulacres » - il habite dans une micro-chambre d’un complexe des condominiums à plusieurs étages où on peut trouver tout – du service d’un psychiatre ou un chapelain jusqu’à la boulangerie.

La situation immobilière est pareille pour le personnage du roman « Simulacres » - il habite dans une micro-chambre d’un complexe des condominiums à plusieurs étages où on peut trouver tout – du service d’un psychiatre ou un chapelain jusqu’à la boulangerie.

Et voici l'histoire de "The Killer". Le personnage principal est Albert Brock, un patient placé en clinique, qui souffre dans la technosphère, ce qui le prive de paix et de joie. Les bracelets radio (radio au poignet), les maisons parlantes, la télévision, le bruit des voitures, la publicité intrusive, la musique assourdissante ne permettent pas à une personne d'être seule avec elle-même. Les autorités le tiennent en laisse en l'appelant au téléphone. Ce n'est pas encore un téléphone portable, mais un appareil qui est toujours avec Brock, dans une voiture équipée d'une radio :

Et voici l'histoire de "The Killer". Le personnage principal est Albert Brock, un patient placé en clinique, qui souffre dans la technosphère, ce qui le prive de paix et de joie. Les bracelets radio (radio au poignet), les maisons parlantes, la télévision, le bruit des voitures, la publicité intrusive, la musique assourdissante ne permettent pas à une personne d'être seule avec elle-même. Les autorités le tiennent en laisse en l'appelant au téléphone. Ce n'est pas encore un téléphone portable, mais un appareil qui est toujours avec Brock, dans une voiture équipée d'une radio :

Readers of Counter-Currents will be familiar — and likely agreeable to — the notion that despite what you heard in school, most all the truly great writers of the XXth century were “men of the Right.” This has been the theme of books like Kerry Bolton’s Artists of the Right: Resisting Decadence,[1] or Jonathan Bowden’s Western Civilization Bites Back.[2]

Readers of Counter-Currents will be familiar — and likely agreeable to — the notion that despite what you heard in school, most all the truly great writers of the XXth century were “men of the Right.” This has been the theme of books like Kerry Bolton’s Artists of the Right: Resisting Decadence,[1] or Jonathan Bowden’s Western Civilization Bites Back.[2] Svensson is certainly straightforward from the start:

Svensson is certainly straightforward from the start: So mostly, Svensson falls back on miniscule tradition; Heinlein, for example, is hardly a Traditional thinker, even before his ’60s-hippie phase, but he certainly meets the “right-wing” criterion.

So mostly, Svensson falls back on miniscule tradition; Heinlein, for example, is hardly a Traditional thinker, even before his ’60s-hippie phase, but he certainly meets the “right-wing” criterion.

Indeed, interviewed elsewhere, Svensson sounds an awful lot like that modern exponent of the Hermetic Tradition Neville Goddard himself:

Indeed, interviewed elsewhere, Svensson sounds an awful lot like that modern exponent of the Hermetic Tradition Neville Goddard himself:

„

„ Parallel zu seiner

Parallel zu seiner