jeudi, 24 décembre 2020

Ray Bradbury : Il n'y aura personne pour vivre dans la "maison intelligente"

Ray Bradbury : Il n'y aura personne pour vivre dans la "maison intelligente"

Valentin Katasonov

Ex: https://www.geopolitica.ru

Traduction de Juan Gabriel Caro Rivera

Plus l'environnement matériel de la vie devient "intelligent", plus les hommes perdent leurs qualités humaines

L'humanité est entraînée vers un "brillant avenir numérique". Nous assistons à la numérisation rapide de tous les aspects de la société et de la vie humaine. Les gens s'attachent à une multitude d'appareils électroniques, sans lesquels ils ne peuvent plus exister. Que ce soit un ordinateur avec Internet et les réseaux sociaux, un téléphone portable avec de nombreuses applications et des cartes bancaires en plastique, des "portefeuilles électroniques", des "navigateurs" dans les voitures, etc.

Un autre domaine de numérisation de la vie personnelle des gens est la "maison intelligente". Il s'agit d'un système de dispositifs électroniques et automatiques capables d'effectuer des actions et de résoudre certaines tâches quotidiennes sans intervention humaine. Certains éléments de la "maison intelligente" font depuis longtemps partie de la vie quotidienne, en particulier de ceux qui ont des revenus élevés. Il s'agit, par exemple, de la régulation automatique du système de chauffage ou de climatisation. De l'allumage et de l'extinction automatiques des lumières, du déclenchement automatique de l’alarme en cas d’incendie ou de fuites d'eau. Ces éléments comprennent un système électronique pour protéger la maison (les locaux) contre les intrusions (sécurité), des interphones, des serrures électroniques, des clés électroniques, etc. Ces systèmes sont une partie importante, mais pas la seule, d'une "maison intelligente". C'est la partie appelée la maison intelligente. Le terme "maison intelligente" a été créé en 1984 par l'Association nationale américaine des constructeurs d'habitations. Aujourd'hui, elle a été adoptée par de nombreuses grandes entreprises et constructeurs.

Le deuxième élément de la "maison intelligente" est l'électroménager "intelligent", qui fait référence au monde des "choses intelligentes". Les appareils électroménagers ont commencé à remplir les maisons il y a plus d'un siècle. Cela a remplacé de nombreuses opérations manuelles à la maison : fours électriques (cuisinières), cafetières, lave-vaisselle, réfrigérateurs domestiques, fers à repasser, grille-pain, etc. La plupart d'entre eux sont aujourd'hui des appareils automatiques, "intelligents". De nombreux types d'appareils ménagers peuvent être rendus encore plus "intelligents" à l'aide de microprocesseurs, qui permettent une autorégulation fine des appareils. Par exemple, il existe des aspirateurs qui peuvent nettoyer une pièce par eux-mêmes (sans aide humaine), en se déplaçant indépendamment sur le sol. Et la même cafetière peut vous faire du café si vous le dites avec votre voix. Et vous pouvez même spécifier la concentration de café dont vous avez besoin. Ces appareils sont souvent classés comme "intelligents". Une maison intelligente suppose qu'elle est pleine de choses intelligentes.

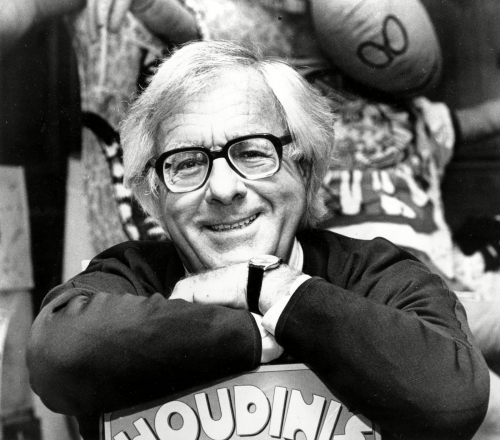

Cependant, ma conversation ne porte pas tant sur la "maison intelligente" que sur l'écrivain américain Ray Bradbury (1). Cette année marque le 100e anniversaire de la naissance de ce classique littéraire de notre époque. Il est décédé récemment, en 2012, à l'âge de 92 ans. Ray Bradbury est généralement connu comme un écrivain qui a travaillé dans le genre de la science-fiction. La dystopie est une littérature portant sur un avenir indésirable. Un écrivain qui crée une dystopie avertit le lecteur d'un avenir indésirable, fait ce qui est en son pouvoir pour empêcher cet avenir de se produire. La dystopie la plus célèbre de Ray Bradbury est Fahrenheit 451 (1953). Peu avant sa mort, l'écrivain a déclaré aux journalistes : "Je n'essaie pas de prédire l'avenir. J'essaie de l'empêcher".

Ray Bradbury a prédit l'émergence d'un monde "intelligent" et a exprimé de sérieux doutes sur le fait qu'une personne dans un environnement "intelligent" se sentirait plus heureuse et plus protégée. Au contraire, c'est tout le contraire. Plus encore. Dans les œuvres de Bradbury, la pensée suivante émerge : plus l'environnement matériel de la vie devient "intelligent", plus les hommes perdent leurs qualités humaines.

Bradbury utilise souvent le terme de "technologie robuste". Je fais référence à ces innovations scientifiques et techniques qui tuent la culture, divisent les gens, les rendent stupides, faibles, insensibles. Bradbury utilise le téléphone comme exemple. Cette invention, selon lui, a permis de relier les gens entre eux, mais à la fin de sa vie, l'écrivain a vu l'émergence du smartphone. Il trouvait une telle innovation assez négative: le smartphone commençait à éloigner les gens. Il a également vivement critiqué les réseaux sociaux, qui remplacent la communication en direct des personnes par des réseaux virtuels.

De nombreux admirateurs de l'œuvre de Bradbury sont surpris par le nombre d'innovations techniques prévues dans ses romans, ses nouvelles et ses histoires. En effet, la naissance de nombre de ces prédictions remonte à 1950. C'est-à-dire qu'ils ont exactement 70 ans. Il s'agit tout d'abord des Chroniques martiennes (recueil d'histoires et d'essais), qui ont rendu cet écrivain de 30 ans mondialement célèbre. Dans les Chroniques martiennes, il convient de souligner le récit visionnaire "Il y aura une pluie douce". Dans la même année 1950, Bradbury publie le terrible récit visionnaire The Veldt. Dans la même ligne se trouve l'histoire The Killer (publiée en 1953, écrite en 1950). Le résultat des Chroniques martiennes et d'une série d'histoires qui a généré le roman Fahrenheit 451, qui évoquait également des "choses intelligentes", dont personne ne rêvait à l'époque aux États-Unis.

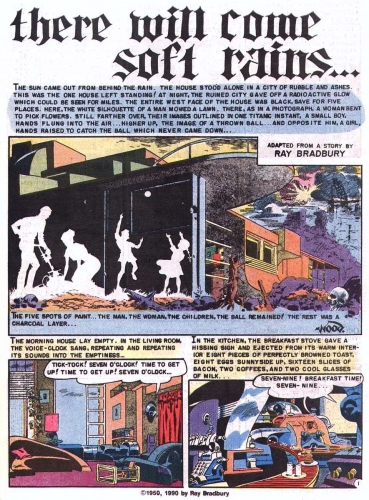

L'histoire There Will Be Gentle Rains est un classique de la dystopie. Certains pensent que c'est un thriller. Les événements décrits dans le récit ne durent qu'une seule journée, du 4 au 5 août 1985. Par la suite, l'auteur a changé la date des événements pour la fixer à 41 ans plus tard (2026). L'accent est mis sur une maison de la ville américaine d'Ellendale, en Californie, appartenant à la famille McClellan. La veille, il y a eu une catastrophe : la ville a été détruite par une attaque nucléaire. Personne n'a survécu, toutes les maisons ont été détruites. Miraculeusement, seule cette maison a survécu. Selon les normes actuelles, une "maison intelligente" classique, mais sans propriétaire, puisque ce propriétaire a été instantanément détruit par une explosion nucléaire (il n'a laissé qu'une empreinte sur un des murs de la maison). Le dernier à mourir a été le chien qui a compris que les propriétaires étaient partis.

Cependant, les machines et les robots de la "maison intelligente" fonctionnent toujours : ils préparent le petit déjeuner, font les lits, nettoient la maison et font la vaisselle. En même temps, comme toujours, ils fredonnent quelque chose, plaisantent, chuchotent tendrement... Tout fonctionne comme la meilleure horloge suisse : "Dans la cuisine, le four soupire d’un ton rauque et de son ventre chaud sortent huit toasts parfaitement faits, quatre œufs sur le plat, seize tranches de bacon, deux tasses de café et deux verres de lait froid. Aujourd'hui à Ellendale, en Californie, le 4 août, deux mille vingt-six", a dit une autre voix depuis le plafond de la cuisine. Il a répété le chiffre trois fois pour mieux s'en souvenir. "Aujourd'hui, c'est l'anniversaire de M. Featherstone, l'anniversaire de mariage de Tilita. La prime d'assurance est due, il est temps de payer l'eau, le gaz et l'électricité. Le robot est un peu confus la nuit. Il est habitué à ce que l'hôtesse lui demande de réciter son poème préféré "Il y aura une douce pluie". Sans attendre la demande habituelle, le robot répète le poème.

L'attaque nucléaire a apparemment causé quelques dommages à l'automatisation de la "maison intelligente" : soudain, un incendie se déclare dans la cuisine, qui engloutit rapidement toute la maison. Les systèmes d'extinction des incendies ne peuvent pas arrêter la propagation du feu. Enfin, l'ordinateur central qui contrôle toute la "maison intelligente" brûle. Les cendres seules restent de la maison. Un seul des murs a miraculeusement survécu avec un appareil audio séparé. Dès le matin, il s'allume et se met à dire en continu : "Nous sommes le 5 août 2026, nous sommes le 5 août 2026...". Le titre de l'histoire est tiré d'un poème de la célèbre poétesse américaine Sara Teasdale (1884-1933). Voici la première et la dernière strophe de ce poème :

Il y aura une douce pluie, il y aura une odeur de terre,

Des sauts rapides et agiles d'une aube à l'autre

Et la nuit, les grenouilles se roulent dans les étangs

Et la floraison des prunes dans les jardins de mousse blanche

Et ni l'oiseau ni le saule ne verseront une larme,

Si la race humaine meurt partout sur la terre.

Le printemps et le printemps trouveront une nouvelle aube

Sans se rendre compte que nous sommes partis.

L'inclusion de ce poème de Ray Bradbury dans votre histoire n'est pas un hasard. L'écrivain a averti il y a 70 ans que les progrès scientifiques et technologiques, pour lesquels toute la communauté "progressiste" prie, pourraient en fait conduire la race humaine à périr sur terre.

Et voici l'histoire de "The Killer". Le personnage principal est Albert Brock, un patient placé en clinique, qui souffre dans la technosphère, ce qui le prive de paix et de joie. Les bracelets radio (radio au poignet), les maisons parlantes, la télévision, le bruit des voitures, la publicité intrusive, la musique assourdissante ne permettent pas à une personne d'être seule avec elle-même. Les autorités le tiennent en laisse en l'appelant au téléphone. Ce n'est pas encore un téléphone portable, mais un appareil qui est toujours avec Brock, dans une voiture équipée d'une radio :

Et voici l'histoire de "The Killer". Le personnage principal est Albert Brock, un patient placé en clinique, qui souffre dans la technosphère, ce qui le prive de paix et de joie. Les bracelets radio (radio au poignet), les maisons parlantes, la télévision, le bruit des voitures, la publicité intrusive, la musique assourdissante ne permettent pas à une personne d'être seule avec elle-même. Les autorités le tiennent en laisse en l'appelant au téléphone. Ce n'est pas encore un téléphone portable, mais un appareil qui est toujours avec Brock, dans une voiture équipée d'une radio :

"C'est aussi pratique pour mes supérieurs : je voyage pour affaires et il y a une radio dans la voiture, et ils peuvent toujours me joindre. Contact ! Dis-le doucement. Contact, bon sang ! Attache tes mains et tes pieds ! Attrape, attrape, écrase, broie avec toutes ces voix de radio. Vous ne pouvez pas sortir de la voiture une minute, vous devez certainement signaler : "Je me suis arrêté à la station-service, je vais aux toilettes." - "C'est bon, Brock, allez-y." "Brock, pourquoi jouez-vous autant ?" - "Je suis désolé, monsieur !"

Le psychiatre essaie de l'aider avec les moyens habituels, mais Albert Brock dirige inopinément l'énergie et la passion dans la technosphère qui empêche une personne de vivre. Il commence à détruire le matériel dont il dispose : téléphone, radio, télévision, etc. Pendant un certain temps, il retrouve la paix et le calme, se sent à nouveau en bonne santé. Mais le médecin qui l'aide tente de ramener le protagoniste à son état initial, estimant que ses actes sont la manifestation d'une exacerbation de la maladie. Malheureusement, il s'agit d'une rébellion solitaire que tout le monde considère comme étant le fait de malades mentaux.

Et voici une autre histoire de Ray Bradbury, The Veldt, publiée pour la première fois en 1950 dans The Saturday Evening Post. Son nom d'origine est Le monde que les enfants ont fait. Les héros de la pièce sont une famille américaine de parents (George et Lydia) et deux enfants nommés Peter et Wendy. Ils vivent dans une maison qui, selon les normes modernes, répond à la définition d'une "maison intelligente". Dans l'histoire, la maison s'appelle "Tout pour le bonheur". Là-bas, les gens n'ont même pas besoin de lever le petit doigt ; tout est fait par des machines, de la cuisson des aliments à la confection des lacets. De plus, les habitants reproduisent des choses agréables (musique, vidéos) avec le soutien émotionnel de machines intelligentes. Les enfants reçoivent cette recharge ludique dans une salle spéciale appelée The Veldt. Ce mot, d’origine afrikaander, signifie la savane (sud-africaine) sauvage, l'Afrique sauvage. Et la technologie de la "maison intelligente" reproduit exactement le paysage de la jungle et de la prairie africaines. Les images qui apparaissent devant les enfants sont indissociables de la réalité. Peter et Wendy aiment vraiment se trouver dans ce monde. En plus de la flore, il existe aussi une faune sous forme de lions sauvages. Les enfants adorent les scènes avec les lions, surtout quand ils mangent les carcasses d'autres animaux. Un passe-temps cher aux enfants dans la pièce Veldt. Mais leur assiduité commence à mettre les parents sur leurs gardes, et ils essaient de limiter le passe-temps favori de leurs enfants dans la pièce Veldt. Le psychologue leur recommande de quitter la "maison intelligente" pendant un certain temps et d’installer toute la famille dans une autre ville. Les enfants demandent à être séparés une nouvelle fois dans la salle Veldt. Les parents sont venus les en enlever, mais les enfants les tuent. En fait, dans la pièce Veldt, le meurtre est devenu la norme (les lions rongent leurs victimes et les mangent). Pour les enfants, Veldt a complètement remplacé le monde réel de leurs parents. Pour rester dans ce monde virtuel, les enfants ont décidé de sacrifier leurs parents qui étaient moins précieux et moins importants.

L'Internet moderne ne nous rappelle-t-il pas le Veldt ? Ray Bradbury a non seulement pu prévoir l'émergence de nouvelles technologies, mais aussi les conséquences désastreuses que ces technologies entraînent. Les romans et les histoires des classiques de la littérature américaine devraient servir d'avertissement à l'humanité plongée dans des jeux dangereux appelés "maison intelligente", "trucs intelligents", "intelligence artificielle" et tout ce qui est appelé "numérisation".

Note :

Source: https://www.fondsk.ru/news/2020/12/02/rej-bredberi-v-umno...

00:41 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : ray bradbury, science fiction, dystopie, littérature, lettres, lettres américaines, littérature américaine |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 11 octobre 2012

L’incubo orwelliano

L’incubo orwelliano. Dalla letteratura distopica al totalitarismo contemporaneo

“Fahrenheit 451” di Bradbury, pubblicato nel 1953, pare debba il suo titolo al grado termico di combustione della carta. Nel futuro descritto dal romanzo la lettura è reato

Roberto Cozzolino

Ex: http://www.rinascita.eu/

Nella letteratura classica dei secoli passati – ed in particolare sul versante filosofico – è stata designata come “utopia” la progettazione, puramente teorica, di una futura società ideale; una società dove sarebbe finalmente verificata l’armoniosa e pacifica convivenza degli individui, resa possibile, secondo i vari Autori, dal buon governo degli amministratori ovvero dal grado di emancipazione raggiunto dalle masse od anche dal progresso tecnologico che avrebbe definitivamente liberato l’uomo dalla schiavitù del lavoro.

L’etimologia del termine associato agli artefici delle opere riconducibili a tale filone letterario, derivante dal greco “ou” e “tópos” – letteralmente “non luogo” –, indica chiaramente per gli stessi l’ovvia consapevolezza di riferirsi a realizzazioni impensabili per la loro epoca; e che potevano semmai indicare una meta ideale verso la quale tendere, o avere valore di critica sferzante della struttura sociale dell’epoca in cui vivevano; da ciò deriva il concetto esteso di utopia come fantastica chimera, qualcosa cioè che risulta estremamente difficile, se non impossibile, realizzare nell’immediato.

Come è noto il termine fu adottato per la prima volta da Tommaso Moro nella sua celebre opera del 1516: “De optimo reipublicae statu deque nova insula Utopia”, in cui si descrive una comunità che risiede, priva di problemi, nell’isola di Utopia, dove vengono applicati metodi di governo d’ispirazione democratica e socialista; in verità il neologismo filologicamente corretto avrebbe dovuto essere “atopia” (senza luogo), con l’uso dell’alfa privativo associato al sostantivo, ma si sostiene da più parti che Moro intendesse consentire un’ambivalenza del termine, riconducibile sia ad “ou” e “tópos” (non luogo) che ad “èu” e “tópos” (luogo buono). Celeberrimo precursore di Moro fu Platone, che nella sua “Politéia” (390 a.C.) propose una forma di governo che tenterà - senza successo - di impostare presso la corte del tiranno Dionigi a Siracusa: una sorta di “comunismo” guidato da filosofi e con una società divisa in classi. Altra famosa opera utopica è “New Atlantis” di Francesco Bacone, del 1626; in essa le innovazioni tecnologiche possedute dagli abitanti dell’isola di Bensalem – fantasioso toponimo derivante dalla conflazione dei nomi di Betlemme e Gerusalemme - costituiscono un enorme supporto alla felicità degli uomini, per i quali la conoscenza diventa strumento di dominio sul mondo.

Citiamo inoltre “La città del Sole” (1602) di Tommaso Campanella – uno stato teocratico retto secondo i principi della religione naturale e basato sulla proprietà comune, riecheggiante l’epopea degli heliopolìtai di Aristonico (131 a. C.) -; “Les aventures de Télémaque, fils d’Ulysse” (1696) di François Fénélon - un viaggio didattico attraverso diversi paesi e forme di governo dell’antichità -; “Voyage en Icarie” (1840) di Étienne Cabet - un sistema di stampo socialistico dove è chiara l’influenza del comunismo egualitario di Babeuf e Buonarroti -; “News from Nowhere” (1890) di William Morris – una delle più anarchiche descrizioni di una società futura -; “Erewhon” (1872) di Samuel Butler – utopia satirica della società vittoriana -; da notare che quest’ultimo titolo é un anagramma di “nowhere”, con chiaro riferimento, come quello dell’opera di Morris, al significato di “utopia”. In questa rapidissima ed incompleta elencazione dei massimi esponenti del pensiero utopico non possiamo tacere i nomi di Owen, Fourier, Saint-Simon, Enfantin e Considérant, ovvero i massimi esponenti del cosiddetto socialismo utopistico (così definito sprezzantemente dai marxisti ortodossi, in contrapposizione al socialismo scientifico), che proposero società ideali sostenute da precise teorie sociopolitiche e che in qualche caso, forti delle loro convinzioni, finirono col rovinarsi economicamente nei tentativi falliti di realizzare i loro sogni. In concomitanza con gli utopici sistemi di società future ebbe ampio sviluppo, sin dal medioevo ma soprattutto nel Rinascimento ed oltre – ed in particolare presso i socialisti utopistici - la progettazione di complessi urbani ideali, dove erano quindi preponderanti su tutti gli altri gli aspetti urbanistici ed architettonici; dal momento che le realizzazioni antropiche sono determinate dalle varie funzioni sociali umane; e queste ultime direttamente dipendenti da orientamenti squisitamente ideologici.

Si noti peraltro che lo stesso socialismo marxista – che rimproverava agli utopisti l’assenza di un rigoroso metodo scientifico nell’analisi della società, il mancato riconoscimento della funzione storica del proletariato ed una eccessiva fiducia nelle possibilità di un riformismo basato sulla solidarietà e la filantropia - può considerarsi una grande utopia; tra l’altro densa di evidenti analogie – oltre ad altrettanto evidenti motivi di conflitto - con molti aspetti delle religioni messianiche del ceppo abramitico, come è stato efficacemente analizzato da diversi autori: ideologia intesa come ortodossia fondamentalista, aspirazioni egualitaristiche, rigida gerarchia, controllo e censura delle “eresie”, presenza di dogmi e di testi sacri, interpretazione dicotomica del mondo e fideistica certezza nella futura affermazione della giustizia universale; al punto da suggerire a Berdjaev che “il comunismo è l’insoddisfazione per il cristianesimo non realizzato”.

Verso la fine del XIX e nel corso del XX secolo prende forma un nuovo genere letterario conosciuto come anti utopia (od anche distopia, pseudoutopia, utopia negativa, cacotopia), che presenta evidenti affinità col genere utopico ma mostra, rispetto a questo, una totale inversione di segno, costituendone quasi un aspetto speculare; se infatti il romanzo utopico prospettava la futura realizzazione di una società migliore, il romanzo distopico prefigura per l’avvenire scenari da incubo, con un’umanità schiavizzata e condannata all’infelicità perpetua sotto il dominio di governi dispotici. In realtà secondo alcuni critici il primo autorevole esempio di antiutopia si ebbe già nel 1726, con la pubblicazione dei “Gulliver’s Travels” di Jonathan Swift, in cui le società immaginate possono essere considerate una grottesca satira dell’ordine sociale esistente. Tra i “moderni” precursori del genere ricordiamo H. G. Wells, che con “The time machine” (1895) ci porta in un lontano futuro per mostrarci un’umanità divisa in due fazioni antagoniste di prede e cacciatori: gli Eloi, esseri fragili e gentili ma parassitari; ed i Morlock, esseri produttivi e mostruosi che vivono nelle viscere della terra, da cui escono per dare la caccia agli Eloi e cibarsene.

“Brave New World”, scritto nel 1932 da Aldous Huxley, descrive un prossimo mondo dove tutto è sacrificabile ad un malinteso mito del progresso in cambio di un apparente benessere, e l’esasperata evoluzione scientifica, gestita da un regime totalitario, ha completamente annullato la libertà individuale. Il bellissimo e troppo poco noto “Noi” di Evgenii Ivanovich Zamjatin, scritto in pieno regime comunista ed a causa del quale l’Autore fu costretto ad espatriare – con le proprie gambe grazie all’intervento di Maxim Gorky -, ci mostra un’antiutopia, scritta in forma di diario, ambientata in un mondo dove i personaggi non hanno un nome, ma al suo posto una sigla numerica e dove tutto è ferreamente regolamentato dall’onnipresente potere. “Fahrenheit 451” di Bradbury, pubblicato nel 1953 come estensione di un racconto apparso nel 1951 (“The Fireman”), pare debba il suo titolo al grado termico di combustione della carta, in quanto nel futuro descritto dal romanzo la lettura è reato e tutti i libri devono essere bruciati, essendo sufficiente, per l’educazione delle masse, il mezzo televisivo controllato dal sistema.

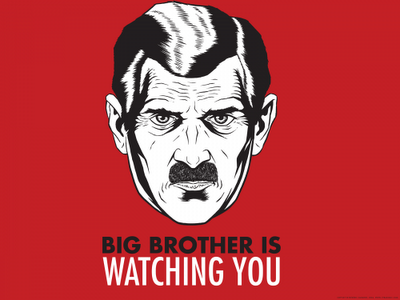

Qualcuno individua chiari elementi distopici anche ne “La leggenda del grande inquisitore” di Dostoevskij, inserita nel suo ultimo lavoro: “I Fratelli Karamazov” (1879) dal sommo romanziere russo. Ma l’opera che realizza l’utopia negativa per eccellenza è, senza dubbio, “Nineteen Eighty-four” di George Orwell, scritto nel 1948 (il titolo è ottenuto scambiando tra loro le ultime due cifre che compongono tale data), dove il Grande Fratello, a capo di una enorme gerarchia costituita dal partito, controlla non solo gli individui ma anche i loro pensieri; l’Autore aveva già dato alle stampe nel 1945 l’altrettanto celebre “Animal Farm”, una feroce satira dello stalinismo scritta sotto forma di favola che, pur essendo già ultimata nel 1943, non risultava politicamente corretto pubblicare prima, dal momento che criticava la forma di governo di una nazione alleata nel recente conflitto mondiale.

In “1984” Winston Smith, il protagonista, membro subalterno del partito che lavora alla modifica di libri ed articoli di giornale pubblicati in passato, in modo che le previsioni fatte dal partito stesso risultino veritiere, non sopporta i condizionamenti della rigida e squallida struttura sociale entro la quale è costretto a vivere e ne infrange molte regole, instaurando tra l’altro un rapporto sentimentale con una compagna, in un mondo in cui è imposta per legge la castità ed il sesso è permesso solo a fini procreativi; nel momento in cui entrambi decidono di collaborare con un’organizzazione clandestina, proprio l’individuo che avrebbe dovuto costituire il contatto col movimento di resistenza si rivela essere invece un agente della psicopolizia che, dopo averli fatti arrestare, li sottopone ad orripilanti tecniche di rieducazione sociopolitica, in modo che si trasformino in individui perfettamente mansueti ed allineati con l’ortodossia del regime.

Il cinema ha tratto massiccia e costante ispirazione dalla letteratura distopica, che per sua natura si presta ottimamente alla trasposizione filmica, spesso contaminandone il genere con altri affini - in particolare quello fantascientifico e quello di fantascienza apocalittica e post-apocalittica. Ci sembra che esistano relativamente poche pellicole che si ispirano dichiaratamente ad una delle opere letterarie citate, rimanendo molto fedeli all’impianto narrativo originario. Ricordiamo tra queste: “Fahrenheit 451” (1966) di François Truffaut, dall’omonimo racconto di Bradbury; “Nel duemila non sorge il sole” (1956) di Michael Anderson ed “Orwell 1984” (1984) di Michael Radford, entrambi ispirati al romanzo di Orwell, come il precedente “1984” (1954), adattamento televisivo di Rudolph Cartier per la BBC; “The Time Machine” (1960) di George Pal, tratto da H. G. Wells e seguito da frequenti remake. Sono invece numerosissime le pellicole liberamente ispirate al “genere” nel suo complesso ma prive di riferimenti puntuali ad una singola opera. Rinunciando ovviamente alla completezza ed all’ordine cronologico ricordiamo alcune tra le più famose: l’intramontabile “Metropolis” (1927), di Fritz Lang; “L’uomo che fuggì dal futuro” (1971), primo lungometraggio di George Lucas; “Alphaville, une étrange aventure de Lemmy Caution” (1965), insolita incursione di Jean-Luc Godard nella fantascienza; il visionario, satirico ed al contempo agghiacciante “Brazil” (1985), di Terry Gilliam, che avrebbe dovuto chiamarsi “1984 ½” per un duplice omaggio ad Orwell e Fellini; “Soylent Green” (1973), di Richard Fleischer, ambientato in un mondo invivibile dove l’eutanasia appare come estrema risorsa; “Zardoz” (1974), di John Boorman, manifesto contro l’utopia progressista; “Rollerball” (1975) di Norman Jewison, con remake (2002) di John Campbell McTiernan, nel quale lo sport violento elargito alle masse diventa strumento di potere; “1997 Escape from New York” (1981) di John Carpenter, dove troviamo l’intera isola di Manhattan trasformata in un enorme ghetto-prigione di massima sicurezza per criminali; del medesimo regista è ”They Live” (1988), dove il potere è detenuto da insospettati alieni; “Terminator” (1984) di James Cameron, primo film di una serie che vede le macchine in guerra con gli uomini; “Twelve Monkeys” (1995), ancora di Gilliam, in cui un viaggiatore del tempo indaga sulle cause di una trascorsa epidemia della razza umana; per finire col totalitarismo virtuale di “Matrix” (1999), spettacolare trilogia dei fratelli Wachowski.

Qualunque siano, ad ogni modo, le differenze tra i vari classici distopici letterari - e tra questi e le loro più o meno fedeli rielaborazioni cinematografiche -, esistono nelle varie visioni di un futuro apocalittico alcuni elementi ricorrenti che riteniamo interessante analizzare; per cercare di capire se i loro Autori fossero solo degli intellettuali disancorati dalla realtà - e pertanto folli “profeti di sciagure” - o, al contrario, individui provvisti di una profonda capacità di analisi ed eccezionalmente lungimiranti quando ammonivano che, se si fosse continuato a percorrere certe strade, si sarebbero realizzati i terribili scenari descritti nei loro romanzi. In effetti uno dei massimi esponenti della letteratura antiutopica, il già citato Aldous Huxley, ventisette anni dopo l’uscita del suo “Brave New World” riesaminava le sue profezie alla luce di avvenimenti recenti col saggio “Brave New World Revisited” (1959), giungendo ad una conclusione inquietante: alcuni elementi dell’utopia negativa che aveva immaginato meno di tre decenni prima erano già entrati a far parte della realtà. E’ stato del resto ampiamente documentato che cambiamenti strutturali anche drastici, che la popolazione rifiuterebbe istintivamente se fossero imposti all’improvviso, vengono invece docilmente accettati se iniettati a piccole dosi nel tessuto sociale ed accompagnati da martellanti campagne massmediatiche. Altra osservazione che merita particolare attenzione è che se quasi tutti – ma non tutti – gli Autori distopici guardavano con preoccupazione, nel momento in cui scrivevano, a varie forme coeve di totalitarismo, oggi invece possiamo individuare proprio nel mondo cosiddetto “libero e democratico” molti degli aspetti più oppressivi da loro denunciati.

Uno di questi è la presenza di una gerarchia, basata prevalentemente sul potere economico, grazie alla quale le divisioni fra classi sociali sono rigide e quasi insormontabili. Si tratta di un’esagerazione? Forse, ma il costante impoverimento della classe media, il degrado della scuola pubblica ed i costi proibitivi dell’istruzione privata, la progressiva scomparsa dello stato sociale e dell’assistenza sanitaria, l’accesso al mondo del lavoro e – di conseguenza - ad una vita dignitosa presentati non come diritto acquisito ma come conquista individuale - uniti al disinvolto uso di clientelismo, raccomandazioni e tangenti da parte della casta che detiene le leve del controllo politico - vanno esattamente in tale direzione; a questo si accompagna la proliferazione di sterminate periferie degradate in tutte le grandi metropoli, a sottolineare - oggi più che nel passato - la separazione anche fisica tra le masse proletarie ed i pochi beneficiari dei vantaggi derivanti dal contatto col potere. Una immediata conseguenza è la scomparsa dei rapporti sociali come concepiti tradizionalmente dall’uomo: le relazioni umane sono dettate esclusivamente dal dogma del vantaggio individuale e del tornaconto personale.

Altro aspetto sicuramente individuabile come comune alla letteratura anti utopistica ed alla nostra società è il reiterato tentativo di soppressione del dissenso, visto come valore negativo in opposizione al conformismo dilagante; al di là dell’apparente pluralismo e libertà di espressione, peraltro sanciti da quasi tutte le costituzioni delle moderne democrazie, risulta chiaro a tutti che, tranne rarissime eccezioni, le coalizioni che si alternano alla guida dei governi, di qualunque colore appaiano, sono sempre espressione dei medesimi gruppi di potere. La propaganda di regime e tutto l’apparato educativo favorisce nella popolazione il culto del proprio sistema di governo, cercando di convincerla che è l’unico - e probabilmente il migliore – possibile. Le voci di reale dissenso presenti vengono o infiltrate dai “servizi” e sapientemente manipolate od emarginate limitando drasticamente, con tutti i mezzi individuabili, il loro raggio d’azione. Il sistema penale inoltre comprende spesso la tortura fisica e psicologica per tutti coloro che sono semplicemente sospettati di attività eversive. Sono consentiti anche gli omicidi mirati, purché, ovviamente, finalizzati al trionfo della “democrazia”.

In molti romanzi distopici la Storia viene continuamente riscritta in modo da risultare in linea con le previsioni ed i desideri del gruppo dominante; in “1984” è previsto un “nemico” che trama costantemente ai danni del governo e contro cui la popolazione è invitata quotidianamente a sfogare tutto il proprio risentimento; nella nostra epoca siamo ormai tristemente abituati a quegli episodi noti come tattica “false flag” od alle madornali ma sempre efficaci “bugie di guerra”, finalizzate ad ottenere il consenso della popolazione per aggredire altri Stati sovrani. Tali manovre sono spesso precedute ed accompagnate dalla minuziosa creazione del nemico da odiare, l’immagine del quale viene assemblata pazientemente, giorno dopo giorno, telegiornale dopo telegiornale, ospitando sui quotidiani e nei talk show di regime l’opinione di “esperti” e le accurate analisi politiche di sedicenti “gruppi dissidenti in esilio”; si arriva a negare – contro ogni evidenza - che il personaggio oggetto della campagna di demonizzazione sia mai stato considerato amico; si presentano come veri filmati realizzati da esperti cineasti dove alcune milizie, agli ordini diretti del novello despota, si abbandonano ad ogni sorta di violenze, tanto più odiose in quanto rivolte ad esseri indifesi quali donne, vecchi, neonati; la decisione di porre fine alla criminale attività del tiranno sarà salutata con entusiasmo crescente da tutta la popolazione. Tutto ciò è naturalmente reso possibile grazie anche alla solerte complicità di una agguerrita e ben remunerata schiera di pennivendoli e gazzettieri governativi, che diffondono come vere le notizie emesse direttamente dalle centrali di disinformazione. Le eventuali e sempre più rare voci contrarie che tentino una efficace controinformazione non hanno, in genere, i mezzi idonei per contrastare in tempo utile le menzogne ufficiali.

Altro interessante – ed eccezionalmente significativo - punto di contatto tra la realtà attuale e la letteratura distopica riguarda il divieto di revisione storica da parte dei singoli ricercatori: tale aspetto, che tra l’altro nega alla Storia il suo carattere scientifico – in quanto questa verrebbe affidata al giudizio di un tribunale piuttosto che alla libera ricerca – denuncia la scellerata volontà del pensiero unico dominante, che introducendo lo psicoreato pretende non solo il dominio sul presente ed il futuro, ma anche sul passato, secondo il motto orwelliano: “Chi controlla il passato controlla il futuro: chi controlla il presente controlla il passato”. Sempre ad Orwell è dovuta l’introduzione del concetto di “bispensiero”, ovvero la capacità di sostenere simultaneamente due opinioni palesemente contraddittorie e di accettarle entrambe come vere – sintetizzata nello slogan del partito: “la libertà è schiavitù, l’ignoranza è forza, la guerra è pace” -; grazie al bispensiero attuale assistiamo oggi a “guerre umanitarie” a seguito delle quali vengono massacrati migliaia di civili ed intere nazioni sono contaminate per molti decenni futuri con sostanze radioattive; ci indottrinano fino alla nausea con tematiche antirazziste ma dobbiamo tollerare come normale l’ingombrante e criminale presenza di una entità che fa del razzismo uno dei suoi elementi fondanti; alcune situazioni negative per la moderna sensibilità – arretratezza della condizione femminile, scarso rispetto delle minoranze, presenza della pena di morte – vengono denunciate ed aspramente contestate se riferibili al “nemico” di turno, tollerate, minimizzate e addirittura ignorate se presenti nel contesto socioculturale di un alleato.

In molti romanzi anti utopisti ed in moltissimi film riferibili a tale genere le agenzie governative paramilitari sono impegnate nella sorveglianza continua dei cittadini. In alcuni casi il controllo può essere sostituito o coadiuvato da potenti e sofisticate reti tecnologiche. Alla fine dell’Ottocento Jeremy Bentham ideò un sistema di carcere, il Panopticon, pensato come una struttura radiale che consentiva ad un unico guardiano – posizionato in una torretta centrale - di vedere, non visto, tutti i detenuti e divenne un modello nella successiva progettazione di molti istituti di pena. Analogamente i cittadini dell’incubo orwelliano sono continuamente spiati dal Grande Fratello, anche nell’intimità delle loro case (per analogia con tale attitudine è stato battezzato in Italia “Grande Fratello” un reality show dove la vita quotidiana dei protagonisti viene costantemente monitorata attraverso telecamere nascoste; risulta che la maggioranza degli adolescenti affezionati a tale demenziale spettacolo di diseducazione di massa ignori i motivi della scelta del titolo). Sembra che in quella che viene ritenuta “la più grande democrazia del mondo” sia imminente la realizzazione del progetto, spacciato come beneficio sanitario, finalizzato a dotare tutti i cittadini di un chip sottocutaneo che produrrà effetti fino ad oggi impensabili in termini di libertà personale. Sicuramente molti saranno indotti ad assecondare senza protestare questo piano criminale, perché efficacemente spaventati e resi insicuri dalla incombente crisi economica, dal terrorismo e dall’incremento della criminalità.

Ancora molto numerose ed indubbiamente interessanti sono le similitudini da individuare tra le apocalittiche visioni degli universi distopici e la moderna società sedicente democratica; lasciamo il piacere di ulteriori scoperte a chi voglia dedicarsi alla lettura di queste coinvolgenti e spesso profetiche opere letterarie, ricordando il monito che Orwell rivolgeva agli intellettuali e che deve essere fatto proprio da tutti gli uomini liberi del mondo: prendere posizione chiara contro ogni tipo di totalitarismo; soprattutto, aggiungiamo noi, quando si celi camaleonticamente sotto improbabili vesti democratiche per perseguire i propri inconfessabili fini.

A tale proposito – sebbene esuli dalle presenti note - è necessario spendere qualche parola sul concetto di stato totalitario, a nostro avviso oggi usato arbitrariamente - se per tale idealtipo si accettano le connotazioni eminentemente negative codificate da Hannah Arendt (“Le origini del totalitarismo”, 1951) -, soprattutto se riferito al periodo dell’Italia fascista, anche se l’aggettivo “totalitario” veniva disinvoltamente usato, naturalmente in una accezione positiva, da Giovanni Gentile e dallo stesso Mussolini, ad indicare che “… per il fascista … nulla … ha valore fuori dallo Stato …”; se è infatti innegabile che durante il ventennio prese forma un regime autoritario è comunque risibile la tesi secondo la quale tutti gli italiani si sarebbero trasformati all’improvviso in pavidi mentecatti ipnotizzati dal gruppo dirigente, peraltro sconfessata dalla nota e storicamente accertata presenza di diverse anime all’interno del movimento; alcune delle quali, autenticamente rivoluzionarie, emersero prepotentemente quando, con la costituzione della Repubblica Sociale Italiana, vennero definitivamente recisi i legami con le forze reazionarie che facevano capo alla Chiesa ed al troppo piccolo re fuggiasco e traditore.

Né ci convincono le smodate lodi dei glorificatori delle democrazie occidentali, dove chi (mal)governa - grazie alle sponsorizzazioni dei potentati economici che finanziano le campagne elettorali - lo fa col consenso di una percentuale infima della popolazione, vista la crescente disaffezione per le urne degli aventi diritto al voto. L’esigenza morale sentita da tutti deve essere quella di vigilare costantemente per denunciare con forza la deriva sociale verso sistemi disumanizzanti e privi di valori condivisibili e tentare di smascherare - e contrastare con ogni mezzo - le progressioni, anche se piccole ed apparentemente innocue, tendenti all’universo schiavizzante dei regimi effettivamente totalitari.

http://www.rinascita.eu/index.php?action=news&id=16899

00:05 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : lettres, lettres anglaises, littérature, littérature anglaise, dystopie, littérature dystopique, george orwell, ray bradbury, anti-utopie, 1984, fahrenheit 451 |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 19 juin 2012

Ray Bradbury. Le mille facce di un genio inafferrabile

Ray Bradbury. Le mille facce di un genio inafferrabile

Parlare di Ray Bradbury significa far correre subito il pensiero ai suoi due capolavori, Cronache marziane (1950) e Fahrenheit 451 (1953), anche se lo scrittore, deceduto ieri a Los Angeles a quasi 92 anni (li avrebbe compiuti il 22 agosto), ha avuto una carriera più che settantennale (avendo esordito a 21 anni nel 1941, su Weird Tales) nel corso della quale ha pubblicato storie di tutti i generi, e non solo quel particolare tipo di fantascienza che a suo tempo si definì «umanistica», comunque tutte caratterizzate dal suo tocco personale, dal suo stile unico, evocativo, dalla singolare aggettivazione che avvolge il lettore senza che se ne accorga.

Con lui scompare uno degli ultimi rappresentanti (è ancora vivo Frederik Pohl, classe 1919) della grande e irripetibile «età d’oro della fantascienza». Pochi lo sapevano, ma negli ultimi anni era bloccato su una sedia a rotelle, però continuava a scrivere con regolarità pur se per interposta persona: ogni mattina per tre ore dettava telefonicamente alla figlia Alexandra, perché non poteva più usare la sua vecchia macchina da scrivere meccanica a causa di un malanno al braccio.

A suo tempo, negli anni Cinquanta-Settanta, ciò che colpì di Bradbury fu la visione malinconica e tragica del destino dell’uomo contemporaneo e futuro preda della massificazione totale, dello sradicamento dell’Io individuale e della sua personalità, succube di una macchinificazione della vita, intendendo con questo non solo i marchingegni meccanici e robotizzati, ma anche la virtualità che in America si stava già imponendo a metà del Novecento, mentre da noi ci si sarebbe accorti di tutto questo soltanto a partire dagli anni Ottanta con il moltiplicarsi dei canali televisivi. Non c’è dunque da meravigliarsi che lo scrittore nei suoi ultimi interventi pubblici se la sia presa con gli aggeggi elettronici che hanno invaso la nostra vita e la condizionano. «Abbiamo troppi telefonini. Troppo internet. Dobbiamo liberarci di quelle macchine», ha detto in un’intervista per il suo novantesimo compleanno al Los Angeles Times. Perché meravigliarsene, come fece a suo tempo qualcuno? È la logica conseguenza delle critiche che alle «macchine», anche se di altro genere, Bradbury ha fatto in tutte le sue opere e specialmente in Fahrenheit 451: anche cellulari, iPad, iPod, lettori elettronici, smartphone lo sono e producono conseguenze. Delle chat e di Facebook ha detto: «Perché tanta fatica per chiacchierare con un cretino col quale non vorremmo avere a che fare se fosse in casa nostra?». La sua crociata contro i deficienti e l’incultura risale ai primordi della sua carriera. Un precursore di certe critiche oggi comuni, insomma.

A suo tempo, negli anni Cinquanta-Settanta, ciò che colpì di Bradbury fu la visione malinconica e tragica del destino dell’uomo contemporaneo e futuro preda della massificazione totale, dello sradicamento dell’Io individuale e della sua personalità, succube di una macchinificazione della vita, intendendo con questo non solo i marchingegni meccanici e robotizzati, ma anche la virtualità che in America si stava già imponendo a metà del Novecento, mentre da noi ci si sarebbe accorti di tutto questo soltanto a partire dagli anni Ottanta con il moltiplicarsi dei canali televisivi. Non c’è dunque da meravigliarsi che lo scrittore nei suoi ultimi interventi pubblici se la sia presa con gli aggeggi elettronici che hanno invaso la nostra vita e la condizionano. «Abbiamo troppi telefonini. Troppo internet. Dobbiamo liberarci di quelle macchine», ha detto in un’intervista per il suo novantesimo compleanno al Los Angeles Times. Perché meravigliarsene, come fece a suo tempo qualcuno? È la logica conseguenza delle critiche che alle «macchine», anche se di altro genere, Bradbury ha fatto in tutte le sue opere e specialmente in Fahrenheit 451: anche cellulari, iPad, iPod, lettori elettronici, smartphone lo sono e producono conseguenze. Delle chat e di Facebook ha detto: «Perché tanta fatica per chiacchierare con un cretino col quale non vorremmo avere a che fare se fosse in casa nostra?». La sua crociata contro i deficienti e l’incultura risale ai primordi della sua carriera. Un precursore di certe critiche oggi comuni, insomma.

Tutto sta in quel capolavoro antiutopico che è appunto Fahrenheit 451. Un libro che è l’esaltazione dell’uomo e della cultura vera dell’uomo, quella trasmessa dai libri e non dalle finzioni virtuali della televisione. Già nel ’51-53 Bradbury immaginava schermi grandi come una parete e la vita falsa che trasmettevano tramite quelle che oggi si chiamano sitcom e vanno avanti per decenni quasi fosse una realtà parallela a quella del telespettatore, o reality show dove la gente comune diventa protagonista attiva (tema, questo, di molti suoi tragici racconti come il famoso La settima vittima). È contro la pandemia televisiva che lo scrittore si scaglia in difesa di un altro tipo di cultura che questa cercava di sommergere e annullare, e non aveva affatto di mira il senatore McCarthy o una specifica dittatura parafascista o paranazista, come volevano dare a intendere certi critici «impegnati» qui in Italia. Fu lo stesso scrittore, con grande delusione di certi suoi fans, a confermarlo: nel 2007, sempre in un’intervista al Los Angeles Times, affermò che il suo famoso romanzo non si doveva interpretare come una critica alla censura o specificatamente al senatore McCarthy, perché era piuttosto una critica alla televisione e al tipo di (in)cultura che essa trasmette. Insomma, Bradbury ce l’aveva e ce l’ha avuta sino all’ultimo, contro la pseudo-informazione, la pseudo-vita, gli pseudo-fatti, quelli che Gillo Dorfles ha battezzato «fattoidi», e che sono ormai la «normalità» delle tv di tutto il mondo, specie in Italia.

In un’altra intervista ha detto: «I libri e le biblioteche sono davvero una parte importante della mia vita, perciò l’idea di scrivere Fahrenheit 451 è stata naturale. Io sono una persona nata per vivere nelle biblioteche». Scoramento profondo, quindi, di tutti i suoi lettori e analizzatori progressisti: nessuna motivazione politica e/o ideologica dietro il famoso romanzo strumentalizzato in tal senso per decenni, anche se, leggendo bene quel che Bradbury scriveva, non era affatto impossibile afferrarlo. Tanto è vero che spesso, negli Stati Uniti, Bradbury si è platealmente irritato quando qualcuno gli voleva spiegare quel che aveva scritto, le sue intenzioni. Come si vede, la tanto apprezzata e semplicistica equivalenza fantascienza/progressista e fantastico/reazionario è una solenne sciocchezza, anche se purtroppo ancora qualcuno ci crede, magari forzando le tesi espresse dagli scrittori nelle loro opere. Bradbury è sempre stato sostenitore di una cultura umanistica e ci ha dato una fantascienza di questo genere con veri e propri capolavori: ma non sta scritto da nessuna parte che ciò sia sinonimo di progressismo ideologico e politico.

* * *

Tratto da Il Giornale del 7 giugno 2012.

00:05 Publié dans Hommages, Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : ray bradbury, littérature, lettres, lettres anglaises, littérature anglaise, science ficiton, littérature dystopique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Ray Bradbury ist tot – Chiffre 451

Götz Kubitschek:

Ray Bradbury ist tot – Chiffre 451

Ex: http://www.sezession.de/

Wer nach den berühmten Dystopien unserer Zeit gefragt wird, nennt George Orwells 1984, Aldois Huxleys Schöne Neue Welt, vielleicht Ernst Jüngers Gläserne Bienen, ganz sicher Das Heerlager der Heiligen von Jean Raspail (wenn er einer von uns ist!) und vor allem den Roman Fahrenheit 451 von Ray Bradbury. „451″ ist eine meiner Lieblingschiffren, und die Hauptfigur aus Bradburys Roman – der Feuerwehrmann Montag – ist Angehöriger der Division Antaios.

Bradbury – geboren 1920 – ist am 5. Juni verstorben. Fahrenheit 451 ist sein bekanntester Roman. In ihm werden Bücher nicht mehr gelesen, sondern verbrannt, wenn der Staat sie findet: Ihre Lektüre mache unglücklich, lenke vom Hier und Heute ab, bringe die Menschen gegeneinander auf. Vor allem berge jedes Stück Literatur etwas Unberechenbares, Freigegebenes, etwas, das plötzlich und an ganz unerwarteter Stelle zu einer Fanfare werden könne. In den Worten Bradburys: „Ein Buch im Haus nebenan ist wie ein scharfgeladenes Gewehr.“

Montag indes greift heimlich nach dem, was ihm gefährlich werden könnte. Er rettet ein paar Dutzend Bücher vor den Flammen, versteckt sie in seinem Haus und vor seiner an Konsum und Seifenopern verlorengegangenen Frau. Heimlich liest er, zweifelt, befreit sich und wird denunziert (von seiner eigenen, an den Konsum und die Indoktrination verlorengegangenen Frau); er kann fliehen und stößt in einem Waldstück auf ein Refugium der Bildung, auf eine sanfte, innerliche Widerstandsinsel, eine Traditionskompanie, eine Hundertschaft von Waldgängern: Leser wandeln auf und ab und lernen ein Werk auswendig, das ihnen besonders am Herzen liegt, um es ein Leben lang zu bewahren, selbst dann noch, wenn das letzte Exemplar verbrannt wäre.

Ich korrespondiere derzeit mit einem bald Achtzigjährigen, der insgesamt sieben Jahre im Gefängnis verbrachte und in dieser Zeit nichts für seinen Geist vorfand als das, was er darin schon mit sich trug. In Dunkelhaft war er allein mit den memorierten Gedichten, Dramenstücken, Prosafetzen, und er war dankbar für jede Zeile, die er in sich fand. Er kannte Fahrenheit 451 noch nicht und las begierig wie ein Student (wie er mir schrieb). Und er schrieb, daß er in Montags Waldstück keinen Prosatext verkörpern würde, wenn er dort wäre, sondern fünfhundert Gedichte – den Ewige Brunnen sozusagen.

Und Sie?

Ellen Kositza:

Nicht jeder kann Bradbury auswendig können

Ich will direkt an Kubitscheks Bradbury-Text anknüpfen: Sein leicht verbrämter Aufruf, das Memorieren poetischer Texte einzuüben, kommt aus berufenem Munde. Kubitschek kann mehr Gedichte aufzusagen, als ich je gelesen habe, gar auf russisch, ohne daß er die Sprache beherrschte. Ein seltener Fleiß, ich werde mir keine Sorgen machen, wenn er mal ins Gefängnis muß.

Ich will direkt an Kubitscheks Bradbury-Text anknüpfen: Sein leicht verbrämter Aufruf, das Memorieren poetischer Texte einzuüben, kommt aus berufenem Munde. Kubitschek kann mehr Gedichte aufzusagen, als ich je gelesen habe, gar auf russisch, ohne daß er die Sprache beherrschte. Ein seltener Fleiß, ich werde mir keine Sorgen machen, wenn er mal ins Gefängnis muß.

In der zeitgenössischen Pädagogik ist vor lauter Selberdenkenmüssen das Auswendiglernen ja stark in den Hintertreffen geraten. Unsere Kinder tun sich nicht besonders schwer damit, es wird ihnen aber kaum – und stets nur minimal – abverlangt. Nun kam es hier im Hause kam öfters vor, daß die müden Kinder inmitten des Abendgebets gähnen mußten; ein bekanntes Phänomen, das dem Nachlassen der Konzentration und weniger mangelnder Frömmigkeit anzulasten ist. Nun lernen wir seit einigen Monaten das Vaterunser in verschiedenen Sprachen, mühsam Zeile für Zeile zwar (so daß für jede Sprache mehrere Wochen benötigt werden), aber die abendliche Leistung zeigt Wirkung; kein Gähnen mehr.

Jetzt gibt es vermehrt Leute, die sich ihre Lieblingszeilen nicht so gut merken können. Es hat nicht jeder den Kopf dafür. Es gilt nicht mehr für gänzlich unzivilisiert, sich ein nettes Lebensmotto mit Farbe unter die Haut ritzen zu lassen. Dann kann man es stets nachlesen oder sich wenigstens vorlesen lassen. Bekanntermaßen hat sich Roman, der deutsche Kandidat des Europäisches Liederwettbewerb, ein gewichtiges Lebensmotto (samt Mikro!) auf die Brust stechen lassen: Never fearful, always hopeful. Eine hübsche, gleichsam allgemeingültige Ermunterung!

Internationale Sangesgrößen haben es ihm vorgemacht. Rihanna trägt die Weisheit never a failure, always a lesson auf der Haut, Katy Perry schürft noch tiefer und ließ sich (Sanskrit!!) Anungaccati Pravaha!, zu deutsch „Go with the flow!“ stechen, und der intellektuell unangefochtene Star des Pophimmels, Lady Gaga, uferte gar aus und verewigte ihren „Lieblingslyriker Rilke“ mit folgen Worten auf einem Körperteil:

“Prüfen Sie, ob er in der tiefsten Stelle Ihres Herzens seine Wurzeln ausstreckt, gestehen Sie sich ein, ob Sie sterben müßten, wenn es Ihnen versagt würde zu schreiben. Dieses vor allem: Fragen Sie sich in der stillsten Stunde Ihrer Nacht: Muss ich schreiben?“

Aber auch (noch) wenig prominente Zeitgenossen mögen es philosophisch-lyrisch. Jessica, Studentin und Trägerin der Playboy-Preises „Cybergirl des Monats“ läßt auf ihrer glatten Haut in wunderschön geschwungener Schrift das Cicero zugewiesene Motto Dum spiro spero blitzen, und jüngst kamen mir hier im wirklich ländlichen Landkreis zwei weitere tätowierte Kalligraphien unter´s Auge: Einmal in fetter Fraktur an strammer Männerwade unterhalb eines kahlrasierten Schädels Carpe Diem, andermal , als Schultertext: Mann muß Chaos in sich tragen, um einen tanzenden Stern zu gebären. Nietzsche hatte , glaub ich, „man“ geschrieben, aber er schrieb wohl mehr so für Männer, und der Spruchträger war tatsächlich männlichen Geschlechts, also hatte ja alles seine Richtigkeit.

Nun mag mancher Tätowierungen an sich für ein Zeichen von Asozialität halten. Wir mögen es mit Güte betrachten: Schlägt sich darin nicht eine Sehnsucht nach Dauer, nach Absolutheit, nach Schwur und Eid nieder? Nicht jeder hat Geld, Zeit, Fähigkeit und Phantasie, ein Haus zu bauen, einen Baum zu pflanzen, ein Kind zu zeugen. Wenn er schon die eigene Haut zu Markte tragen muß, dann wenigstens symbolisch aufgeladen! Nun fragt sich manche/r schlicht: womit bloß? Stellvertretend möchte ich “ Adrijanaa“ zitieren, die auf einem Forum namens gofeminin händeringend fragt:

Hallo zusammen!

Ich liebe Tattoos und möchte endlich selbst eins haben. Habe mich für ein Zitat auf dem Schulterblatt entschieden (so ähnlichw ie bei Megan Fox). Das Problem: Mir föllt keins ein. Es ist schon irgednwie blöd im Internet nach zu fragen, aber ich bin momentan einfach sowas von einfallslos. Ich lege in diesem Fall auch nicht viel Wert darauf, ob jemand diesen Spruch schon auf eienr Körperstelle besitzt oder nicht. Ein englischer Zitat wäre am besten. Es können Weisheiten, Zitate aus Songlyrics oder Filmen sein. Falls ihr ein paar Ideen habt, wäre ich sehr froh darüber, was von euch zu hören!LG, Adi

Die Adi wurde dann von einigen „Mitusern“ nachdrücklich gefragt, ob sie denn nicht selbst auf ein paar fesche Zitate käme, die ihr aus der „Seele“ sprächen. Aber:

Ich überleg ja schon die ganze Zeit. . . Hab einige gute Lieder, die ich ganz gerne mag, aber die Texte sind manchmal zu primitiv für ein Tattoo. . . Es ist nicht so einfach

Dabei ist es eben doch ganz einfach! Es gibt bereits einige Netzseiten mit hübschen Sprüchen, die unter die Haut gehen könnten. In einem entsprechenden Ratgeberforum für tätowierbare Sprüche habe ich den hier gefunden:

Wer singt und lacht, braucht Therapie.

Alfred Adler

Das ist tiefsinnig, und mit etwas Mühe könnte man es sogar auswendig lernen – für den Fall, daß man das Zitat im Nacken oder auf dem Po unterbringen will.

00:05 Publié dans Hommages, Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : ray bradbury, hommages, littérature, littérature anglaise, lettres, lettres anglaises, dystopie, littérature dystopique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 07 juin 2012

Ray Bradbury, R.I.P.

Ray Bradbury, R.I.P.

By John Morgan

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Ray Bradbury, the writer best known for his novels The Martian Chronicles and Fahrenheit 451, as well as a hundreds of short stories, passed away on Tuesday, June 5 at the age of 91. With him we have lost not only one of America’s greatest writers, but also one of our last genuine writers.

However, I don’t use either of these words – genuine or writer – lightly. I say writer, because I most emphatically do believe that Bradbury, while certainly not one of the most “deep” or sophisticated writers of the past century, certainly came closer to capturing the Angst of our age better than just about anyone else.

I very deliberately did not call him a “science fiction writer,” either, since, as he himself once pointed out, the only one of his major works that could be accurately defined as science fiction is Fahrenheit 451, while the bulk of his work could be more accurately be described as fantasy or horror fiction, with some mainstream works, such as Dandelion Wine, included as well.

As for “genuine,” I used that word for several reasons. One is that Bradbury was part of a vanishing set of writers who learned how to write before America became a post-literate, “information” society that looked to television and, later, the Internet rather than books for entertainment and social commentary. Another is that Bradbury, by his own account, became a writer because of an innate need to write – both because he felt he had a calling for it, and because he quite literally depended on his writing for his livelihood.

I remember reading him recount how, back in 1949 when he was staying at the YMCA in New York and desperately attempting to find a publisher for his short stories about Mars, an editor at Doubleday advised him to turn the book into a novel instead, as novels tend to be more marketable than collections of stories. Bradbury then stayed up all night at the Y, adding a superstructure to his Mars stories modeled on Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, and thus The Martian Chronicles was born.

That used to be the crucible in which great writers were born. Writers were made of equal parts inspiration and determination, prepared to risk everything in the hope, often bordering on insanity, that someone else would actually like what they were doing. These days in America, if someone decides he wants to be a writer, he usually ends up taking creative writing courses at a college or university, and then, if he’s really driven, he’ll continue on to graduate school and get a Master of Fine Arts degree, attending endless “workshops” where teachers of less-than-dazzling talent of their own try to teach him how to write in a style that will appeal to the editors of the prestigious literary magazines – magazines that only a few thousand people nationwide actually read, but which count for everything in the world of academic literary writing.

If he perseveres and actually manages to publish a few things, and is a bit lucky, he can then find a cozy tenure-track position at some school, teaching writing to other writing students, and giving him the leisure time to write books that will only ever be of interest to other MFA students and professors of writing, since the incestuous world of academic writing is the only world he’s ever lived in. With a few exceptions, that is the state of the field of literary writing in America today. The only living American writers I can think of off the top of my head who I would term “genuine” writers of the same caliber as Bradbury would be Cormac McCarthy, Don DeLillo, and Tito Perdue. They are a vanishing breed.

One might ask why Bradbury should matter to readers of Counter-Currents. One reason is that Bradbury was one of the few people still engaged in a process that is fast becoming a rarity – namely, the actual production of “Western culture,” rather than mere lamentation at its absence. He was very much a writer in the Western, and more specifically American, literary tradition. There is very little overt political content to his work, however, and apart from his public objections to Michael Moore stealing the name of his 2004 film, Fahrenheit 9/11, from his book without permission (a complaint which Bradbury insisted was not politically motivated), as far as I knew, he had never done anything political at all.

In looking over the coverage of Bradbury’s death in the online media, however, I came across a tribute in the National Review entitled “Ray Bradbury, a Great Conservative,” which describes how he was initially a staunch Democrat but started to become disillusioned with liberalism during Lyndon Johnson’s administration, and became more and more of a conservative after that. The article quoted Bradbury as saying in 2010, “I think our country is in need of a revolution. There is too much government today. We’ve got to remember the government should be by the people, of the people, and for the people.” That’s good to know, but I still view Bradbury as essentially an apolitical man.

For me personally, the most relevant thing in Bradbury’s work is his anti-modern spirit. This is why it’s ridiculous to try to classify him as a science fiction writer. Bradbury made his bones as a writer in the 1940s and ’50s, at a time when the vast majority of science fiction was about one-dimensional characters serving as chess pieces in a game of depicting futuristic technology or some fantastic alien world. This is the tradition into which today’s “hard” science fiction falls – stories which are more about being scientifically and technologically plausible than interesting as literature.

Bradbury was never a part of this school. If a rocket appears in a Bradbury story, it’s just a rocket – he assumes you know what one is, and leaves all the technical details to your imagination. This isn’t just laziness on his part – in truth, Bradbury saw advancing technology as a threatening thing, and in his own life he was actually a technophobe who never learned to drive and who apparently refused to fly for much of his life. In the final years of his life, to his credit, he also resisted allowing his works to be turned into e-books, claiming that American life had become too mechanized – although apparently, he changed his mind about this, since Fahrenheit 451 was released as a Kindle in 2010 (ironically enough).

The most important aspect of a Bradbury tale is the depth of feeling and passion felt by the characters, and the uncompromising demand they make to remain human in the face of technology and other popular trends of modernization. Bradbury’s best stories are about solitary men who sense that their souls are being threatened by forces driven by the massive engines of progress, and who then embark on an insane battle which they know they cannot win, but which they also know is preferable to continuing to live as one of the mindless herd.

The quintessential character of this type in Bradbury’s corpus is Guy Montag in 1953’s Fahrenheit 451. In this future America (as I recall he never states exactly when it takes place), all books have been banned for decades, television has taken on the character of what is now termed “virtual reality” and dominates most citizens’ lives, presidents are elected on the basis of their looks rather than their policies, actual communication between individuals never rises above the banal, suicide and drug addiction are rife, and personalities never develop beyond childish immaturity.

Montag is a firefighter, but now that all buildings are fireproof, their only job is to show up whenever books are discovered so that they can be promptly burned. Montag grows curious, however, and eventually starts to read some of the books, and discovers the world that has been denied to him. Once exposed to it, he can’t go back to the mindless world he knew before. He ends up conspiring to destroy the firemen, leaves his television-addicted wife, kills the Fire Chief, goes on the run, and ends up joining a small, underground sect of derelict literati in the countryside who have each committed a book to memory, so that they can preserve some of them without fear of arrest. The book ends as America is destroyed in a long-anticipated nuclear war, and Montag and his fellows begin to walk back toward the ruins of the cities, determined to use their knowledge to rebuild a genuine civilization once again.

This is incredibly radical stuff. These are Evola’s “men among the ruins,” doing their part to save something of a genuine tradition even when all seems lost, in the hope that, eventually, a new world will arise. It’s amazing that Fahrenheit 451 is often required reading in public school courses, when you think about it, even though the popular wisdom is that the book is about the “dangers of censorship” – which is rather like saying that Moby Dick is a story about a man who is chasing a whale. The world Bradbury depicts says much more about the dark side of modern life, and is much more horrifying than mere “censorship.” He is a poet for the man who stands by tradition while being at war with the modern world all around. One of my favorite passages of the book has Montag attempting to read the Book of Matthew on a commuter train, while an obnoxious commercial for toothpaste blares in the background, making it impossible to think. Such moments remain strikingly relevant and symbolic.

I’ve always been struck that George Orwell’s Nineteen-Eighty-Four is held up as the classic dystopian novel. While Nineteen-Eighty-Four has considerable merit in its own right, it is also quite obvious by comparing the two that Bradbury had a much greater understanding of the real dangers lurking in Western civilization in the mid-20th century, and of how they would end up playing out in our time. Orwell’s dystopia is about a crushing, all-powerful government that rules with an iron fist, something that seems quite dated today.

Bradbury’s dystopia really isn’t all that different from the America we now inhabit, where the soft touch of commercialization and materialism is used to enforce state power instead. It’s true that books haven’t actually been banned, although they have been rendered irrelevant.

Another classic Bradbury tale of a man rebelling against the spirit of his times is “Usher II,” which was included in The Martian Chronicles and is in part an homage to Edgar Allan Poe, Bradbury’s literary mentor. In this story, we learn that America has imposed moral laws on its citizens, and as a result, nothing deemed disturbing is permitted. A man named William Stendahl, frustrated with the lack of freedom on Earth, goes to the fledgling colony on Mars, where he builds a massive, automated haunted house based on Poe’s stories. Hearing of it, government officials named “Moral Climate Monitors” are dispatched to investigate its decency.

When they arrive, they immediately decide to have the house torn down, but Stendahl convinces them to go through the house once before passing judgment on it. He also reveals that he has had android doubles of all the officials made. As they walk through the house, the officials see the android versions of themselves being killed, one by one, in particularly gruesome fashion, as Stendahl condemns them for their efforts to sanitize the human experience. Finally, when he gets the Chief Inspector alone, Stendahl reveals that it is the real officials who have been getting killed, while the android doubles were looking on. Stendahl traps the Chief Inspector behind a wall in imitation of “The Cask of Amontillado,” and then whisks away by helicopter as the house collapses into the surrounding swamp.

Although perhaps the simplest version of his “man among the ruins” character is the one in his story “The Pedestrian” (1953), which is about life in 2053, when television has become so predominant that no one leaves their homes at night. Leonard Mead takes a walk through his city, enjoying the solitude he finds and wishing to differentiate himself from those who are forever huddled in front of their screens. Crime, we are told, has disappeared, since television keeps everyone constantly amused. He is finally stopped by a police car on his walk, and when he can’t offer any explanation for why he is walking, he is arrested and told that he will be taken to a psychiatric ward. The crowning dénouement comes when Mead is forced into the car and realizes that there are no police officers, and that it is completely automated.

From these examples, it should be clear that Bradbury nursed a hatred for the modern world that bordered on the violent, as evinced by the extreme reactions many of his characters have to it. The modern world for Bradbury, as it is for the traditionalists, is a place of soulless materialism, sterility, and stupidity divorced from anything authentic, as well as from the past.

My personal favorite since childhood among Bradbury’s rebellious characters, however, is Spender, in “And the Moon Be Still as Bright,” from The Martian Chronicles. In this story, following the disappearance of several earlier expeditions to Mars from Earth, a large and heavily-armed group of astronauts lands on Mars, only to discover that all of the Martians have recently died as a result of being exposed to chickenpox by the previous expeditions from Earth, and against which their immune systems had no defense.

Spender is enchanted by the remnants of the Martian civilization, but his colleagues are mostly contemptuous of it, breaking things and spending their time getting drunk. Spender disappears for several weeks, exploring the Martian ruins on his own, and then returns, lulling his colleagues into a false sense of security and then gunning down six of them. He flees into the hills, where he is pursued by the commander of the expedition, Captain Wilder, and a large force of armed men.

Wilder approaches Spender one last time before he attacks him, to try to talk him into surrendering. The conversation they have has always been among my favorite passages, and I think it’s worth quoting in full:

The captain considered his cigarette. “Why did you do it?”

Spender quietly laid his pistol at his feet. “Because I’ve seen that what these Martians had was just as good as anything we’ll ever hope to have. They stopped where we should have stopped a hundred years ago. I’ve walked in their cities and I know these people and I’d be glad to call them my ancestors.”

“They have a beautiful city there.” The captain nodded at one of several places.

“It’s not that alone. Yes, their cities are good. They knew how to blend art into their living. It’s always been a thing apart for Americans. Art was something you kept in the crazy son’s room upstairs. Art was something you took in Sunday doses, mixed with religion, perhaps. Well, these Martians have art and religion and everything.”

“You think they knew what it was all about, do you?”

“For my money.”

“And for that reason you started shooting people.”

“When I was a kid my folks took me to visit Mexico City. I’ll always remember the way my father acted – loud and big. And my mother didn’t like the people because they were dark and didn’t wash enough. And my sister wouldn’t talk to most of them. I was the only one really liked it. And I can see my mother and father coming to Mars and acting the same way here.

“Anything that’s strange is no good to the average American. If it doesn’t have Chicago plumbing, it’s nonsense. The thought of that! Oh God, the thought of that! And then – the war. You heard the congressional speeches before we left. If things work out they hope to establish three atomic research and atom bomb depots on Mars. That means Mars is finished; all this wonderful stuff gone. How would you feel if a Martian vomited stale liquor on the White House floor?”

The captain said nothing but listened.

Spender continued: “And then the other power interests coming up. The mineral men and the travel men. Do you remember what happened to Mexico when Cortez and his very fine good friends arrived from Spain? A whole civilization destroyed by greedy, righteous bigots. History will never forgive Cortez.”

“You haven’t acted ethically yourself today,” observed the captain.

“What could I do? Argue with you? It’s simply me against the whole crooked grinding greedy setup on Earth. They’ll be flopping their filthy atoms bombs up here, fighting for bases to have wars. Isn’t it enough they’ve ruined one planet, without ruining another; do they have to foul someone else’s manger? The simple-minded windbags. When I got up here I felt I was not only free of their so-called culture, I felt I was free of their ethics and their customs. I’m out of their frame of reference, I thought. All I have to do is kill you all off and live my own life.”

…

The captain nodded. “Tell me about your civilization here,” he said, waving his hand at the mountain towns.

“They knew how to live with nature and get along with nature. They didn’t try too hard to be all men and no animal. That’s the mistake we made when Darwin showed up. We embraced him and Huxley and Freud, all smiles. And then we discovered that Darwin and our religions didn’t mix. Or at least we didn’t think they did, We were fools. We tried to budge Darwin and Huxley and Freud. They wouldn’t move very well. So, like idiots, we tried knocking down religion.

“We succeeded pretty well. We lost our faith and went around wondering what life was for. If art was no more than a frustrated outflinging of desire, if religion was no more than self-delusion, what good was life? Faith had always given us answers to all things. But it all went down the drain with Freud and Darwin. We were and still are a lost people.”

“And these Martians are a found people?” inquired the captain.

“Yes. They knew how to combine science and religion so the two worked side by side, neither denying the other, each enriching the other.”

“That sounds ideal.”

…

Spender led him over into a little Martian village built all of cool perfect marble. There were great friezes of beautiful animals, white-limbed cat things and yellow-limbed sun symbols, and statues of bull-like creatures and statues of men and women and huge fine-featured dogs.

“There’s your answer, Captain.”

“I don’t see.”

“The Martians discovered the secret of life among animals. The animal does not question life. It lives. Its very reason for living is life; it enjoys and relishes life. You see – the statuary, the animal symbols, again and again.”

“It looks pagan.”

“On the contrary, those are God symbols, symbols of life. Man had become too much man and not enough animal on Mars too. And the men of Mars realized that in order to survive they would have to forgo asking that one question any longer: Why live? Life was its own answer. Life was the propagation of more life and the living of as good a life is possible. The Martians realized that they asked the question ‘Why live at all?’ at the height of some period of war and despair, when there was no answer. But once the civilization calmed, quieted, and wars ceased, the question became senseless in a new way. Life was now good and needed no arguments.”

“It sounds as if the Martians were quite naïve.”

“Only when it paid to be naïve. They quit trying too hard to destroy everything, to humble everything. They blended religion and art and science because, at base, science is no more than an investigation of a miracle we can never explain, and art is an interpretation of that miracle. They never let science crush the aesthetic and the beautiful. It’s all simply a matter of degree. An Earth Man thinks: ‘In that picture, color does not exist, really. A scientist can prove that color is only the way the cells are placed in a certain material to reflect light. Therefore, color is not really an actual part of things I happen to see.’ A Martian, far cleverer, would say: “This is a fine picture. It came from the hand and the mind of a man inspired. Its idea and its color are from life. This thing is good.’”

There was a pause. Sitting in the afternoon sun, the captain looked curiously around at the little silent cool town.

“I’d like to live here,” he said.

“You may if you want.”

“You ask me that?”

“Will any of those men under you ever really understand all this? They’re professional cynics, and it’s too late for them. Why do you want to go back with them? So you can keep up with the Joneses? To buy a gyro just like Smith has? To listen to music with your pocketbook instead of your glands? There’s a little patio down here with a reel of Martian music in it at least fifty thousand years old. It still plays. Music you’ll never hear in your life. You could hear it. There are books. I’ve gotten on well in reading them already. You could sit and read.”

“It all sounds quite wonderful, Spender.”

“But you won’t stay?”

“No. Thanks, anyway.”

“And you certainly won’t let me stay without trouble. I’ll have to kill you all.”

“You’re optimistic.”

“I have something to fight for and live for; that makes me a better killer. I’ve got what amounts to a religion, now. It’s learning how to breathe all over again. And how to lie in the sun getting a tan, letting the sun work into you. And how to hear music and how to read a book. What does your civilization offer?”

This is the crux of the traditionalist argument in a nutshell. I would add, however, that while it can be beneficial for a Western traditionalist to look to the other traditional civilizations of old for instruction and inspiration, the past of our own civilization is just as alien to modern man as a Martian civilization would be. The real battle is not that of the “West” versus the intrusion of outside elements, because even the “West” of today is not really Western anymore. The battle of our time is, at essence, really about the traditional versus the modern. Everything else is just a manifestation of this basic struggle. And this is a war that is happening everywhere. And it begs the question: what, exactly, are we fighting for? For the traditionalist, at least, the fight must, and can only be for our souls.

Spender adopted the Breivik approach in his war for the traditional, sparking violence that had no chance of success (in the story, he is killed). We can understand the motives and frustrations that lead to such actions, but ultimately, they don’t get us anywhere. The more correct approach, however, is Montag’s – of going underground, and trying to preserve our traditions, until the moment arises when more is possible. As Evola put it, one must become one of “those who have kept watch during the long night [so that they] might greet those who will arrive with the new dawn.” I doubt whether Bradbury had ever heard of the traditionalists, but he was certainly one of them in spirit, if not in doctrine.