The starting point of Spinoza’s philosophy is that man is ultimately responsible for his own fate. He rejected the belief of Maimonides (1135-1204) that God was a rational being, arguing instead that if God were truly omnipotent, then God would have the power to be exactly what he wanted to be (rational, arational, or otherwise). And if God could recreate himself, then so could man, which meant Spinoza also rejected the concept of evil because “the evil passions are evil only with a view to human utility . . . ” In other words, the things men considered to be wicked or immoral were merely problems that could be managed and eventually overcome. Spinoza’s ardent belief in progress and the potential of men to correct the evils of human behavior would ultimately lay the groundwork for the modern liberal state, but he could only do this, as Strauss demonstrates, by showing “the way toward a new religion or religiousness which was to inspire a wholly new kind of society, a new kind of Church.” To accomplish this task, Spinoza wrote his Theologico-Politcal Treatise in which he used a bait-and-switch technique of attacking Judaism… in order to lead his Christian readers into a general critique of all religions.

The Jewish philosopher Hermann Cohen (1842–1918) strongly opposed the work of Spinoza and charged him with conceiving of the state entirely in terms of power politics, divorced from religion and morality, thus rendering the state above religion. Cohen also indicted Spinoza for denying that the God of Israel was the God of all mankind and for reducing Jewish religion to a doctrine of the Jewish state. The former was blasphemy and the latter served to diminish the Torah to human origin, both of which rendered Spinoza blind to biblical prophecy and hence to the core of Judaism. Cohen also believed Spinoza’s critique of the Jewish religion to be ripe with contradictions. For instance, it made little sense to single out the Mosaic Law as the suppressing force of philosophy when it was unclear that Jesus Christ himself championed the freedom of philosophy. But what may have incensed Cohen the most about Spinoza’s Treatise was the claim that Mosaic Law was particularistic and tribal and served no other end than the earthly or political felicity of the Jewish nation. In this regards, the moral implications of Spinoza’s religious transgressions were far less damning than his disloyalty to the Jewish people. Cohen believed Spinoza deserved excommunication because he gave comfort and aid to the enemies of the Jews by first idealizing Christianity and then indulging in every Christian prejudice against Judaism.

The vitriol with which Cohen condemned Spinoza was impressive and should be all too familiar to members of the alternative Right. He regarded the defector’s behavior as “unnatural” and a “humanly incomprehensible act of treason.” To act this way, Spinoza must have been a disturbed man “possessed by an evil demon.” Cohen’s criticism is reminiscent of the frequent diatribes against “racists” as vile and mentally deformed creatures in need of sensitivity training if not medication.

Leo Strauss’s interpretation of Spinoza’s behavior discounted the self-hating Jew explanation and suggested that Cohen had not paid “sufficient attention to the harsh necessity to which Spinoza bowed by writing in the manner in which he wrote.” Heresy and blasphemy of Christianity were offenses punishable by death, which deterred most philosophers from directly challenging the Church. Jews in particular felt this intimidation because they were haunted by the experience of the Spanish Inquisition.

But Strauss did not believe the deterrent factor alone explained Spinoza’s decision to single out Judaism. Instead, Spinoza seemed to be employing a carefully thought-out strategy to reach a wider audience with a message that could be absorbed, internalized, and expanded upon . . . that would lead his audience towards a greater truth. Put bluntly, Spinoza’s purpose was to show mankind the way towards a liberal society and his strategy was one of subterfuge.

Spinoza was writing for a devoted Christian audience and thus had to modify his message accordingly. This meant playing off their anti-Semitic prejudices and urging them to free “spiritual Christianity from all carnal Jewish relics,” like the resurrection of the body. By making the Old Testament the scapegoat for everything he found objectionable in Christianity, Spinoza presented his general argument against religious particularism in a form that was palatable to Christians. To be clear, his disparagement of Judaism and the Mosaic Law was not insincere. Spinoza was striving to create a new universal religion for both Jews and Christians, and he also believed Jews had more to overcome to get there, since, as Strauss relates, “Moses’ religion is a political law” and “to adhere to his religion as he proclaimed it is incompatible with being the citizen of any other state.” Cohen’s misunderstanding was to think that Spinoza wanted the eradication of religious devotion to end with Judaism. In other words, he failed to follow Spinoza’s thought that freedom of philosophy required a liberal state that was neither Christian nor Jewish. The Jews may have had to be liberated from Judaism—but the Christians also had to be liberated from Christianity.

In the Introduction to Persecution and the Art of Writing, Strauss gives an excellent accounting of this argumentation style as it was advocated by the Islamic philosopher Farabi. Farabi (c. 872—950) said that when Socrates was confronted with the decision to conform to what he held to be false opinions and the wrong ways of life of his fellow citizens, he stubbornly chose nonconformity—and was punished with death. Farabi believed this may have been the suitable choice in dealing with the elite, but it was ill-advised to attempt this approach with the vulgar. Dealings with the common man required a strategy styled on Plato, that is, gradually replacing accepted opinions with the truth, or an approximation of the truth—changing minds by provisionally accepting conventional wisdom. More specifically, and as it applies to the Spinoza example, Farabi believed that “conformity with the opinions of the religious community in which one is brought up is a necessary qualification for the future philosopher.”

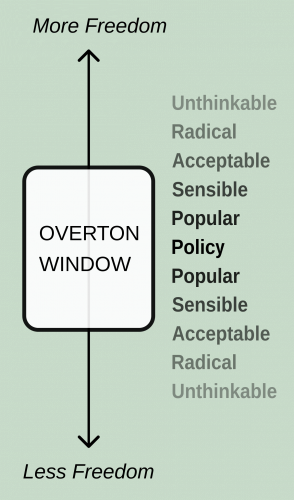

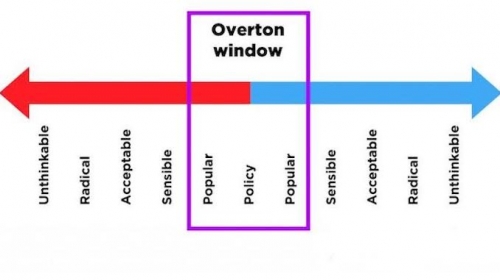

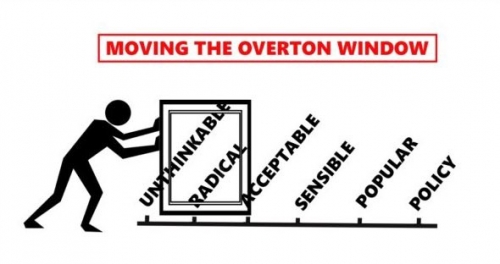

The strategy outlined above should not be understood simply in terms of avoiding persecution, because what is really at issue here may be the best method of philosophy. If you want to reach the most people with your message in a way that you can actually change their minds about something, the new truth you are presenting cannot flagrantly contradict their sacrosanct beliefs. In other words, when challenging orthodoxy in any form, it is always prudent to signal left before turning right. Appearing loyal and loving to what is already loved—and then transforming it from within—is far more effective than challenging it head-on. This is philosophy at the highest level, where the means of delivery are as important as the message being delivered.

It should be of particular interest to the alternative Right that signaling one way and turning the other was the strategy used by the egalitarians when they convinced the Western World to embrace racial equality. Had the Boas Cult simply declared the racial beliefs of Western Man to be immoral and completely unfounded, their arguments would have fallen on deaf ears. What they did instead was moderate their position with the claim that all perceived inequalities among the races were caused by variances in culture. This concession earned Boas and his followers the trust of their target audience because it soothed Western Man’s pride, conformed to his prejudices, and did not encumber him with charges of racial injustice. Cultural inequality actually placed the burden of responsibility on minorities who needed to get their act together by adopting Western Man’s superior way of life. Boas and his followers probably never really believed this, but they had to make a tactical settlement in order to be heard, which is to say, they had to appear loyal to Western Civilization before they could get any traction challenging its long-held assumption of racial inequality. What followed next is well known to most readers of AlternativeRight.com…

What the alternative Right can learn from Spinoza—and Boas—is a strategy of subterfuge. If we desire to reach audiences beyond the readers of this website, then we must understand, as Spinoza and Boas did, that the gradual replacement of accepted opinions has to be accompanied by a provisional acceptance of the conventional wisdom of our time. In other words, we must be willing to signal left before turning right. Only then will we be able to reach wider audiences in a way that might provoke them to question the unquestionable.

It is probably asking a lot of alternative Right writers to appear loyal to, let alone adoring of, the gods of multiculturalism, diversity, and egalitarianism, but employing such a strategy when writing for politically correct audiences would be far more effective than directly challenging orthodoxy. One such tactic might be to support some of the ideals of egalitarianism and then show how they are contradicted by others. For example, if the intention of multiculturalism is to preserve the unique cultural identity of various racial elements in this country, then we could argue that what is really happening is the destruction of diversity by the merging and watering down of cultures into unrecognizable forms. As “true” proponents of diversity, we would be taking the moral high ground in claiming that minority cultures are under siege by “universalism” and “McDonald-ization” and that their preservation can only be achieved through the separation of cultures, not blending them together into a homogenous blob. This form of attack would be far more palatable to mainstream audiences than directly confronting multiculturalism with charges of reverse racism. We could make the corollary claim that multiculturalism itself is ethnocentric in its origins—i.e. it was invented by White people—and oppressive to minority groups that did not develop a similar ideological standpoint on their own.

Unfortunately, emphasizing the inherent conflict between multiculturalism and diversity may not always work, since actual global diversity is being preserved by non-Western countries that do not tolerate immigration or cultural diffusion. The only culture that is actually being destroyed by multiculturalism is Western culture, a consequence unlikely to concern most readers of the mainstream press who believe America, the “proposition nation” united by creed, has been spared the backwards ideology of racial identity. Nevertheless, an argument that multiculturalism is oppressive to minorities could have more traction.

Multiculturalism is often claimed to be a philosophy of universalism, but the intolerance its followers have for non-believers is a clear indication of its particularism. Internalizing this conceptual paradox has been unproblematic for most all PC types (truly, accepting irreconcilable ideas seems to go hand-in-hand with orthodoxy.) Forcing nonbelievers to convert to multiculturalism is also comfortably sanctioned because the principal subjects of this oppression are Whites. If, however, we can reframe the discussion in such a way that multiculturalism appears to be an ideology forced on minorities to their own detriment, then the reaction from the politically correct would be far different.

The key to bringing down egalitarianism from the inside could therefore be the vilification of multiculturalism as a ruling-class conspiracy. Similar to Spinoza who played off the anti-Semite prejudices of Christians, so should we play off the prejudices and neurotic suspicions the politically correct have for Whites. This might be done effectively with class-struggle arguments that link multiculturalism with cheap labor and the exploitation of the Third World by evil White capitalists. An even more powerful argument could be made that multiculturalism prevents non-White peoples from achieving their own unique destiny and subordinates them to a decadent White ideology. (This argument also carries the benefit of actually being true.) It is more than likely that similar arguments have already been made by vigilantly obsessed members of the Left who are constantly on guard for “White privilege” in society. We should cite these liberal experts, expand upon their arguments, and contribute as much as we can to the reinterpretation of multiculturalism as a racist ideology.

In other words, to awaken the politically correct from their indoctrinated slumber, we should convincingly accuse them of being guilty of that which they proclaim to be the greatest of sins.

Collapsing the pillar of multiculturalism might not be enough to bring down egalitarianism, but this should be the first step in a protracted campaign of attrition and political subterfuge. For our revolution to be successful, we must be guided by the self-acknowledgement of the weakness of our current position. Tactical settlements have to be made and finding ways to challenge the orthodoxy by signaling left before turning right should become a necessary part of our long-term strategy.

There may come a point, if we are not already there, when egalitarianism becomes so deeply ingrained in our society that it cannot be defeated through outright confrontation. The best way to challenge orthodoxy of this kind will be through its metamorphosis or reshaping. Such a strategy should not be used at places like Alternative Right, a place where we can be honest about our strategies and goals, but we must begin to think beyond our limited reach here and start sending soldiers back into the ranks of the politically correct to bring down the orthodoxy from within.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg