samedi, 01 mai 2021

Le Magicien de Davos et le Grand Reset

17:14 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, klaus schwab, grand reset, grande réinitialisation |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Rethinking Chinese School of IR from the Perspective of Strategic Essentialism

Rethinking Chinese School of IR from the Perspective of Strategic Essentialism

As early as 1977 Stanley Hoffmann claimed that International Relations (IR) is an American social science (Hoffmann 1977), and according to Ann Tickner (2013), little has changed since then. Mainstream IR scholars perceive different regions of the world as test cases for their theories rather than as sources of theory in themselves. Thereby, the “non-West” became a domain that IR theorists perceived as backward; a domain which requires instruction in order to reach the “end of history” that Western modernity encapsulates (Fukuyama 1992). The phenomenon of American-centrism is closely related to the experience of the United States as a world hegemonic power after World War II. Although US hegemony has often been challenged by other countries in the world, its hegemonic status has never been replaced. Even if other countries looked like they would surpass the US at certain times (the Soviet Union in the 1970s, and Japan in the 1980s), they actually did not have the global, sustainable and all-round appeal of the American model. Therefore, American hegemony in the contemporary world not only enjoys technological, economic, and political superiority, but is also cultural, ideational and ideological.

However, any great power in history has its rise and fall, and the United States is no exception. The financial crisis in 2008, Brexit, the emergence of populism in Western countries, as well as the rise of non-Western countries, have challenged the current liberal order led by the United States. First of all, the stability of American society itself has been declining in recent years, especially under Trump’s administration. Racial divisions, coupled with other accumulated social and economic problems, have plunged the United States into serious trouble.

The COVID-19 pandemic that began in 2020 has weakened the West as a role model for governance and accelerated the transfer of power and influence from the West to the “rest.” In addition, the voice of developing countries and non-Western regions has become stronger in the past few decades as their wealth and power has increased. The combined nominal GDP of the BRICS countries, for instance, accounts for approximately one-quarter of the world’s total GDP. Some scholars have pointed out that the norms, institutions, and value systems promoted internationally by the West are disintegrating. The world is entering a “post-Western era” (Munich Security Report 2017).

The views and experiences of non-Western subjects have increasingly been recognized as an indispensable part of the discipline, which is a consequence of the decline of the West and the wider dissemination of non-Western cultural and philosophical concepts. Various research agendas and appeals have been put forward around this theme. Among the most representative and influential are two initiatives: “Non-Western/Global IR” and “Post-Western IR.” Advocates of Non-Western/Global relations theory, such as Amitav Acharya and Barry Buzan, not only criticize the Western-centrism of the discipline, but also advocate the establishment of IR research based on the histories and cultures of other regions, and encourage the development of non-Western IR theories (See Acharya and Buzan 2010; 2019). The “World Beyond the West” research series (World Beyond the West), initiated by Ann Tickner, Ole Wæver, David Blaney and others, hope to present the local knowledge production practiced by multiple sites, so as to criticize Western-centrism in the discipline, and to respond to the political and ethical challenges faced by the discipline in the post-Western era. Both initiatives expect to develop diverse IR theories and concepts based on “non-Western” historical experience, thoughts and viewpoints.

The rise of interest in non-Western thought in the field of IR has had a positive significance for the development of Chinese IR theory. Many Chinese scholars believe that a Chinese School of IR should be established. For these advocates, Chinese IR not only needs to develop its own epistemological system to understand international relations from China’s perspective; it can also contribute to discussion of what kind of world order China wants. Qin Yaqing, one of the most representative advocates of the Chinese School, believes that the formation of the Chinese School is not only possible but also inevitable. As he states, the Chinese School has three sources of thought from which it can draw nourishment, namely: (1) the Tianxia concept and the practice of the tributary system, (2) modern communist revolutionary thought and practice, and (3) the experience of reform and opening up. Judging from the efforts of Chinese scholars in recent years, most of their efforts have focused on the use of Chinese history, culture and traditional philosophical ideas (Qin 2006). Among them, Yan Xuetong’s moral realism, Zhao Tingyang’s Tianxia system, and Qin Yaqing’s theory of relationality are most influential.

Yan’s moral realism tries to learn from the concept of “humane authority” in Chinese pre-Qin thought as a source of knowledge and ideas in order to reconceptualize the realist view of power. According to Yan, humane authority is not something that one can strive for; rather, it is acquired by winning the hearts of the people through setting an example of virtue and morality. In this vein, virtues and morality are qualities that can be inherent in the conduct of the state and its leaders, and which can influence others to act in one’s favor. It is the source of “political power”(See Yan, Bell and Sun 2011; Yan 2018). Zhao’s Tianxia system draws from an idealized version of the Tianxiasystem of the Zhou dynasty (c. 1046–256 BC) as the paradigmatic model. He argues that the system was an all-inclusive geographical, psychological, and institutional term. It therefore belongs to all humans equally and is more peace-driven than the Westphalian system which has dominated the world order for centuries (See Zhao 2006; Zhao and Tao 2019). Qin’s theory is centered around the concept of relationality, or guanxi, an idea that is embedded in Confucianism. From a Chinese relational perspective, the international society is not as simple as just comprising of independent entities acting in an egoistically rational way in response to the given structures. Instead, it is a complex web of relations made up of states related to one another in different ways (See Qin 2009; 2016; 2018).

The nascent popularity of the Chinese School has received many criticisms in the IR subject area, the most important of which are the following two criticisms. The first argues that the Chinese School’s references to historical documents and classics are either inaccurate or overly romanticized. It is a kind of anachronism, which also infers an imperious form of Chinese exceptionalism – a form of wishful thinking that “China will be different from any other great power in its behavior or disposition” (Kim 2016). The second criticism is that the knowledge developed by Chinese School is only used to legitimize the rise of China. As Nele Noesselt (2015) notes, the search for a Chinese paradigm of IR mainly aims “to safeguard China’s national interests and to legitimize the one-party system.” The above two criticisms are valid, but not unique to China, and by this standard much other work in IR would also have to be discounted. American IR scholarship also uses source material anachronistically, as critics of realism have observed, and its agenda often reflects US interests and concerns. As E.H. Carr noted in his letter to Hoffman in 1977, “What is this thing called international relations in the “English speaking countries” other than the “study” about how to “run the world from positions of strength”?…[it] was little more than a rationalization for the exercise of power by the dominant nations over the weak” (Carr 2016: xxix).

Yan Xuetong

Of course, making comparisons between American hegemony and its connection to mainstream IR on the one hand, and the rise of China with the Chinese School on the other, does not by itself justify the enterprise of the Chinese School from the critical IR perspective.

It is worth mentioning that on various occasions critics like Callahan (2008) have been cautious about the Chinese School as merely another familiar hegemonic design. To some extent, Chinese School scholars are indeed replicating the mainstream western IR theory and its problems (Chen 2010). Attempts by Yan, Zhao and Qin to reinvigorate traditional Chinese concepts – i.e. humane authority, the Tianxia system, and relationality – actually channel the Chinese Schools of IR into American mainstream IR discourse – i.e. a realist notion of power, a liberal logic of cosmopolitanism, and a constructivist idea of relationality. The Chinese School uses, against the West, concepts and themes that mainstream IR currently uses against the non-Western world. As Shani (2008) points out, true post-Western theories should not only mimic modern Western discourse; they must develop a critical discourse from within non-Western traditions, liberating non-Western regions from Western dominance. However, one might ask: is it possible that imitating Western discourse can constitute a kind of critical resistance? In order to think about this issue, it is worth looking at Bhabha’s concept of “mimicry.”

For Bhabha, “mimicry” is a complex, ambiguous, and contradictory form of representation, and it is constantly producing difference/différance and transcendence. As Bhabha notes (1994: 86), “the discourse of mimicry is constructed around an ambivalence: in order to be effective, mimicry must continually produce its slippage, it excess, its difference.” As a result, imitation by the Chinese School is not simply to duplicate the Western discourse, but to change Western concepts and practices to bring them more into line with Chinese local conditions. “Almost the same, but not quite.” Thus, non-Western scholars including the Chinese School can still make novel and innovative contributions to the literature of IR through hybridization, mimicry and the modification of the initial notions, as Turton and Freire (2016) note. More importantly, this mimicry is a concealed and destructive form of resistance in the anti-colonial strategy. Firstly, imitating the West will create similarities between non-Western theories and Western theories, which in turn confuses the identity of the West. Moreover, the relationship between the “enunciator” and the one who is articulated can potentially be reversed. Whether in support or in opposition, mainstream IR scholarship has been forced to respond to various ideas, concepts and approaches proposed by Chinese School scholars. Thirdly, the Chinese School also verifies that the European experience is a local experience. This is readily exposed when the starting points of mainstream IR – often taken for granted – are used in different contexts.

Nevertheless, there seems to be an issue at the heart of the enterprises of the Chinese School from Bhabha’s colonial resistance perspective. To Bhabha (1994: 37), “hierarchical claims to the inherent originality or ‘purity’ of cultures are untenable, even before we resort to empirical historical instances that demonstrate their hybridity.” Undeniably, the Chinese School has manifested several degrees of essentialism in its account of Chinese history and political thoughts, believing that Chinese culture have a homogenous, nonmalleable, and deep-rooted essence. It has indeed juxtaposed China and the West, essentializing and fixating on the existence of “Chinese culture,” which in nature is hybrid. When Orientalist IR meets Occidentalist IR, hatred and conflict will become possible and perpetuate questionable practices in world politics. In that context, the enterprise of the Chinese School might close down the creative space needed to imagine a different way of engagement. Essentialism is something of a taboo in the critical line of IR scholarship. However, when critical theory’s criticism of essentialism is too extreme, it may threaten the base on which resistance depends. In order to meaningfully challenge the hegemony, we need a site of agency, or a subject. A theoretical difficulty derived from this point of view is the extent to which a degree of essentialism is desirable.

To Spivak, essentialism is the object to be deconstructed, however, deconstruction depends on essentialism. As she stated (1990: 11), “I think it’s absolutely on target to take a stand against the discourse of essentialism…But strategically, we cannot.” On the issue of feminism, Spivak opposes the so-called feminine nature. She believes that it is practically impossible to define “women.” An implication of defining women is the creation of a strict binary opposition, a dualistic view of gender, and as a deconstructionist, she is against positing such dualistic notions. Although she opposes defining an absolute and fixed nature of women, from the standpoint of political struggle, she believes that the historical and concrete nature of women still exists and can be used as a weapon of struggle. In light of Spivak’s thought, it is inevitable to adhere to essentialism to a certain extent when engaging in post-Western theories, although we must be vigilant. In other words, the Chinese School as a “strategy” is not permanent but is specific to the situation of non-Western voices needing to be heard on the global stage, noting that the main challenge in the IR discipline today is to address the legacy of “Western hegemony.”

To conclude, the rise of the Chinese School has stimulated discussions, ignited debates, and sparked inspiration among IR scholars. It has challenged Western hegemony within international relations as well as the study of it. As pointed out at the inception of this article, the field of IR theory has been highly Eurocentric to date and international relations are dominated by the Western hegemony. Hence, there is no need to discard Chinese School perspectives altogether. Rather, we need to use the Chinese School strategically and critically, rather than treating them as purely objective standpoints that produce truths. IR knowledge of all sorts needs to be produced with a reflective spirit.

References:

Acharya, A., & Buzan, B. (2010). Non-Western international relations theory : Perspectives on and beyond Asia. London ; New York: Routledge.

Acharya, Amitav & Buzan, Barry. (2019). The Making of Global International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bhabha, Homi (1994). The location of culture. London [etc.]: Routledge.

Callahan, William A. (2008). Chinese Visions of World Order: Post-Hegemonic or a New Hegemony? International Studies Review, 10(4), 749-761.

Carr, Edward H. (1939/2016). The twenty years’ crisis, 1919-1939 : An introduction to the study of international relations. London: Macmillan.

Chen, Ching-Chang. (2011). The absence of non-western IR theory in Asia reconsidered. International Relations of the Asia-Pacific, 11(1), 1-23.

Fukuyama, F. (1992). The end of history and the last man. New York, NY [etc.]: Free Press [etc.].

Hoffmann, S., An American social science: International relations. Daedalus, 106 (1977), pp. 41-60.

Kim, Hun Joon. (2016). Will IR Theory with Chinese Characteristics be a Powerful Alternative? The Chinese Journal of International Politics, 9(1), 59-79.

Munich Security Report (2017). Post truth, post West, post order? Munich Security Report 2017. https://issat.dcaf.ch/Learn/Resource-Library/Policy-and-R...

Noesselt, Nele. (2015). Revisiting the Debate on Constructing a Theory of International Relations with Chinese Characteristics. The China Quarterly (London), 222(222), 430-448.

Qin, Yaqing. (2006). The possibility and necessity of a Chinese School of international relations theory (in Chinese), World Economics and Politics, 2006:3, pp.7-13.

Qin, Yaqing. (2016) A relational theory of world politics’, International Studies Review, 18:1, pp.33–47.

Qin, Yaqing. (2018). A Relational Theory of World Politics. Cambridge University Press.

Shani, Giorgio. (2008). Toward a Post-Western IR: The “Umma,” “Khalsa Panth,” and Critical International Relations Theory. International Studies Review, 10(4), 722-734.

Tickner, Arlene B. (2013) ‘Core, Periphery and (Neo)imperialist International Relations’, European Journal of International Relations, 19:3, pp. 627-646.

Turton, Helen Louise, & Freire, Lucas G. (2016). Peripheral possibilities: Revealing originality and encouraging dialogue through a reconsideration of ‘marginal’ IR scholarship. Journal of International Relations and Development, 19(4), 534-557.

Spivak, G., & Harasym, S. (1990). The post-colonial critic : Interviews, strategies, dialogues. New York, NY [etc.]: Routledge.

Worlding Beyond the West: https://www.routledge.com/Worlding-Beyond-the-West/book-s....

Yan, Xuetong, Bell, Daniel A, Zhe, Sun, & Ryden, Edmund. (2013). Ancient Chinese thought, modern Chinese power (The Princeton-China Series). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Yan Xuetong. (2019). Leadership and the Rise of Great Powers (Vol. 1, The Princeton-China Series). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Zhao, Tingyang. (2006). Rethinking Empire from a Chinese Concept ‘All-under-Heaven’ (Tian-xia, ). Social Identities, 12(1), 29-41.

Zhao, T., & Tao, L. (2019). Redefining a philosophy for world governance (Palgrave pivot).

14:15 Publié dans Actualité, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : chine, relations internationales, théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques, philosophie politique, asie, affairesasiatiques, géopolitique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Les Émirats et la France contre la Turquie: la guerre au cœur de l'Afrique

Les Émirats et la France contre la Turquie: la guerre au cœur de l'Afrique

Lorenzo Vita

Ex : https://it.insideover.com/

Le schéma est toujours le même: la France et les Émirats d'un côté, la Turquie de l'autre. Des puissances opposées s'affrontent du Moyen-Orient à la Méditerranée orientale en passant par l'Afrique du Nord. Dorénavant, elles vont aussi se défier au Sahel et en Afrique centrale: cette bande de terre africaine de plus en plus au centre des intérêts mondiaux.

Le ministère de la défense à Abu Dhabi a envoyé un message précis. Les EAU ont lancé les premiers vols logistiques pour soutenir les efforts de la France et de l'alliance dirigée par Paris dans la "lutte contre le terrorisme dans la région du Sahel". Selon l'agence de presse officielle émiratie, Wam, le gouvernement des EAU a déclaré qu'il était "désireux de contribuer à assurer la sécurité et la stabilité dans la région". Une expression qui a plusieurs facettes, surtout dans une région où les équilibres non seulement régionaux mais aussi internationaux sont en jeu. Car il est clair que l'intérêt de la France et des Emirats n'est pas seulement celui de stabiliser la zone pour soutenir les nations sahéliennes, mais aussi celui d'éviter que des forces contraires au programme d'Abu Dhabi et de Paris (donc les forces turques) parviennent à prendre le contrôle d'une zone particulièrement importante tant pour les ressources énergétiques que pour le contrôle des flux migratoires. Ainsi que la Libye, véritable théâtre d'un "grand jeu" nord-africain.

Pour les Émirats et pour la France, l'ennemi public numéro un en ce moment est la Turquie. Et la démarche d'Abu Dhabi et de Paris doit être lue principalement dans une optique anti-Ankara, surtout après la mort d'Idriss Deby. La mort du président du Tchad a été un véritable coup de semonce. Comme l'écrit Filippo Ivardi Ganapini pour Il Domani, l'assassinat du leader de N'Djamena, par les rebelles du Fact conduit inévitablement à deux possibilités: la poursuite d'une transition militaire très difficile ou l'entrée dans la capitale des rebelles qui, selon des sources locales, sont soutenus par la Turquie et le Qatar. Un danger également réitéré par l'historien et analyste Roland Lombardi qui a confirmé à Al Monitor que "le Tchad de Deby est le 'mur' qui bloque et empêche la progression de l'islamisme et de l'influence turque en Afrique". La chute de ce "mur" est donc le véritable problème qui a déclenché l'entrée en lice des Émirats, la Sparte du Golfe, une puissance qui participe désormais au défi lancé aux Turcs et aux Qataris partout où il existe une force liée à Doha et à Ankara. Des sources grecques confirment cette thèse, et il y a aussi ceux qui parlent d'un intérêt turc pour quelques avant-postes, petits mais significatifs, au Niger et au Tchad, non seulement pour défier les Français sur le terrain, ce qui constitue également un défi lancé par Ankara à la présence française au Fezzan.

Le contrôle du Tchad, à ce moment-là, devient donc essentiel. La porte d'entrée sud de la Libye, en particulier la Cyrénaïque, est la clé d'un nouveau point de pression dans le jeu qui se joue pour contrôler le pays d'Afrique du Nord. Mais c'est aussi exclure une puissance rivale d'un pays fondamental dans la lutte pour le cœur de l'Afrique et pour les ressources de la zone. C'est un lieu qui intéresse tout le monde, Français, Turcs, Émiratis, Qataris, Russes, Égyptiens et Soudanais. Et dans ce contexte, il y a aussi les puissances européennes, que Paris voudrait impliquer dans les délicates opérations au Sahel pour éviter d'avoir à supporter trop longtemps le poids de la campagne militaire contre les rebelles et les terroristes islamistes marginaux. Il n'est donc pas surprenant que les blocs qui se défient au Tchad et dans tout le Sahel soient toujours les mêmes. En effet, l'élan de la Turquie vers l'Afrique s’oppose aux intérêts français, à l'expansionnisme des Émirats et suscite les craintes de l'Égypte.

00:52 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, géopolitique, politique internationale, tchad, afrique, affaires africaines |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

First Horse Warriors - Botai,Yamnaya

00:44 Publié dans archéologie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : proto-histoire, archéologie, botai, yamnaya, peuples cavaliers, peuples de la steppe |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

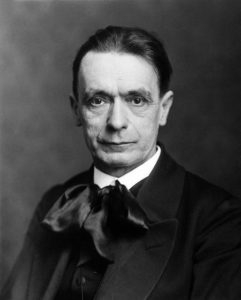

Steiner et Goethe: intuition et expérience dans la science holistique

Steiner et Goethe: intuition et expérience dans la science holistique

Par Giovanni Sessa

Ex : https://www.ereticamente.net/

Goethe était, pour la culture européenne, un véritable aimant. Les intellectuels de premier rang des 19ème et 20ème siècles s'y sont confrontés. Pour n'en citer que quelques-uns: Hegel, Schelling, Nietzsche, George, Löwith. Même le père de l'anthroposophie, Rudolf Steiner, comme le reconnaît James Webb, avait dans le "génie de Weimar" un point de référence essentiel. De plus, un poète, un homme de lettres et un philosophe de sa stature ne pouvait être négligé par les vives curiosités qui animaient les recherches de Steiner. Chargé d'éditer les écrits scientifiques du penseur romantique, Steiner a traité ce domaine particulier mais très important de la recherche de Goethe dans un volume qui a été récemment porté à la connaissance des lecteurs par Iduna editrice (pour les commandes: associazione.iduna@gmail.com , pp. 248, euro 20,00). Il s'agit d'une reconstruction attentive et organique des intérêts naturalistes de Goethe, mais aussi de ses écrits sur le sujet, que l'auteur parcourt et discute avec compétence, animé d'un vif intérêt, motivé qu'il était par la tentative de dépasser les limites matérialistes et accumulatives de la science moderne. Steiner montre que ce champ de recherche était vivant chez Goethe depuis sa jeunesse. A ce moment historique, dans le domaine de la connaissance, une doctrine de simples principes, incarnée par la philosophie de Wolf, et une: "science sans principes [...] chacune était infructueuse pour l'autre" (p. 6). Les investigations de Werther étaient guidées, au contraire, par le concept de vie, à la lumière duquel il comprenait que les manifestations extérieures du monde naturel sont dominées par un principe intérieur et que, dans chaque partie, dans chaque organe d'une entité de la nature, le tout agit. D'où la connotation holistique évidente de l'approche de la physis par Goethe. Cela ne signifie pas que le savant dédaignait l'observation empirique, au contraire! Il la considérait comme centrale, mais pour dévoiler les profondeurs de la vie, elle devait être menée avec les yeux de l'esprit. En 1807, dans l'introduction à la Théorie de la métamorphose, l'Allemand écrit que le regard porté sur la nature montre, à un degré préliminaire, que les formes y sont ondulantes, transitoires. À cet égard, Steiner explique: "Il oppose cette ondulation, en tant qu'élément constant, à l'idée, c'est-à-dire à "un quid tenu ferme dans l'expérience seulement pour un moment" (p. 8).

Goethe était, pour la culture européenne, un véritable aimant. Les intellectuels de premier rang des 19ème et 20ème siècles s'y sont confrontés. Pour n'en citer que quelques-uns: Hegel, Schelling, Nietzsche, George, Löwith. Même le père de l'anthroposophie, Rudolf Steiner, comme le reconnaît James Webb, avait dans le "génie de Weimar" un point de référence essentiel. De plus, un poète, un homme de lettres et un philosophe de sa stature ne pouvait être négligé par les vives curiosités qui animaient les recherches de Steiner. Chargé d'éditer les écrits scientifiques du penseur romantique, Steiner a traité ce domaine particulier mais très important de la recherche de Goethe dans un volume qui a été récemment porté à la connaissance des lecteurs par Iduna editrice (pour les commandes: associazione.iduna@gmail.com , pp. 248, euro 20,00). Il s'agit d'une reconstruction attentive et organique des intérêts naturalistes de Goethe, mais aussi de ses écrits sur le sujet, que l'auteur parcourt et discute avec compétence, animé d'un vif intérêt, motivé qu'il était par la tentative de dépasser les limites matérialistes et accumulatives de la science moderne. Steiner montre que ce champ de recherche était vivant chez Goethe depuis sa jeunesse. A ce moment historique, dans le domaine de la connaissance, une doctrine de simples principes, incarnée par la philosophie de Wolf, et une: "science sans principes [...] chacune était infructueuse pour l'autre" (p. 6). Les investigations de Werther étaient guidées, au contraire, par le concept de vie, à la lumière duquel il comprenait que les manifestations extérieures du monde naturel sont dominées par un principe intérieur et que, dans chaque partie, dans chaque organe d'une entité de la nature, le tout agit. D'où la connotation holistique évidente de l'approche de la physis par Goethe. Cela ne signifie pas que le savant dédaignait l'observation empirique, au contraire! Il la considérait comme centrale, mais pour dévoiler les profondeurs de la vie, elle devait être menée avec les yeux de l'esprit. En 1807, dans l'introduction à la Théorie de la métamorphose, l'Allemand écrit que le regard porté sur la nature montre, à un degré préliminaire, que les formes y sont ondulantes, transitoires. À cet égard, Steiner explique: "Il oppose cette ondulation, en tant qu'élément constant, à l'idée, c'est-à-dire à "un quid tenu ferme dans l'expérience seulement pour un moment" (p. 8).

Les romantiques étaient également parvenus à cette idée de vie cosmique grâce aux travaux d'alchimie, développés avec la collaboration de von Klettenberg et grâce à sa lecture de Paracelse. Il est resté lié pendant une courte période à cette relation mystique avec les forces de la nature: même s'il n'a jamais perdu l'idée de l'univers comme un immense organisme. Il a identifié le mécanicisme d'Holbach comme l'ennemi à battre dans ce domaine d'étude. Il se tourne vers la botanique, poussé par le travail qu'il fait dans le jardin que lui a offert le duc Charles-Auguste. Il passait des journées entières dans la forêt de Thuringe: il y a appris à aimer les mousses et les lichens. Il a lu Linné, dont la méthode de classification devait, selon lui, être complétée par la recherche de ce quid qui reste inchangé dans les nombreuses formes végétales différentes. Il a trouvé la confirmation de la "plante originelle" dans les observations faites au cours de ses voyages, notamment en Italie. Il reconnaît que dans cette "forme fondatrice": "réside la possibilité de variations infinies, de sorte que de l'unité naît la multiplicité" (p. 15).

Avec ce "type", la nature joue, donnant naissance à la multiplicité de la vie. Contrairement à Darwin, qui considérait que la dimension constante de la nature n'existait pas, étant donné la présence vérifiable de la variabilité des aspects extérieurs du monde végétal et animal, Goethe est parti à la recherche de cette dernière, découvrant: 1) le "type", c'est-à-dire la loi qui se manifeste dans les organismes (l'animalité de l'animal); 2) l'action réciproque d'interaction entre l'organisme et la nature inorganique (adaptation et lutte pour l'existence). Darwin ne s'était arrêté que sur ce dernier aspect. En 1790, Goethe expose sa théorie de la métamorphose: "Ce concept est celui d'une expansion et d'une contraction alternées" (p. 21) des entités. Dans la graine, la plante est contractée. Avec les feuilles, sa première expansion se produit. Dans le calice, les forces reviennent se contracter en un point axial, tandis que la corolle témoigne d'une nouvelle expansion. Étamines et pistil sont l'expression de la contraction suivante, fruit de la dernière expansion végétale, qui cache en elle la nouvelle graine. C'est un processus d'entéléchie cyclique. Quant aux différences entre le monde animal et le monde humain, la science de l'époque pensait que seuls les animaux possédaient, entre les deux parties symétriques de la mâchoire supérieure, l'os intermaxillaire. Goethe, en 1784, a montré l'inanité de cette thèse. Cela impliquait que les éléments: "répartis chez les animaux, se réunissent en harmonie dans la figure humaine" (p. 35). Goethe l'avait déjà compris dans ses études de physiognomonie, où la structure osseuse du corps humain renvoyait à la position proéminente de la tête, indiquant, d'un point de vue symbolique, le destin spirituel, et non chosal, de l'être humain. Bref, pour Goethe, dans les organismes: "Toutes les qualités sensibles apparaissent [...] comme les conséquences d'un état qui n'est plus perceptible par les sens" (p. 47). Le savant y parvenait grâce à ce que Spinoza avait défini comme une connaissance d'un troisième type, la scientia intuitiva. En effet, rappelle Steiner, le deus sive natura de Spinoza est le contenu idéal du monde, c'est Dieu qui se donne dans les entités, car quelque chose de la physis est vivifié de l'intérieur, par l'idée. Alors que le concept de l'intellect est une somme d'observation et d'analyse, l'idée est le résultat de l'expérience directe et non médiatisée de la raison. Il s'agit là, selon Steiner, d'un idéalisme empirique. Goethe, en dialogue avec les grands noms de l'idéalisme, reconnaît à la pensée la faculté d'aller au-delà du sensible, la capacité de saisir l'idée comme ‘’forme’’ de la nature: "La perception de l'idée dans la réalité est la véritable communion de l'homme " (p. 84). C'est un processus de ‘’cosmisation’’ de l'humain.

Avec ce "type", la nature joue, donnant naissance à la multiplicité de la vie. Contrairement à Darwin, qui considérait que la dimension constante de la nature n'existait pas, étant donné la présence vérifiable de la variabilité des aspects extérieurs du monde végétal et animal, Goethe est parti à la recherche de cette dernière, découvrant: 1) le "type", c'est-à-dire la loi qui se manifeste dans les organismes (l'animalité de l'animal); 2) l'action réciproque d'interaction entre l'organisme et la nature inorganique (adaptation et lutte pour l'existence). Darwin ne s'était arrêté que sur ce dernier aspect. En 1790, Goethe expose sa théorie de la métamorphose: "Ce concept est celui d'une expansion et d'une contraction alternées" (p. 21) des entités. Dans la graine, la plante est contractée. Avec les feuilles, sa première expansion se produit. Dans le calice, les forces reviennent se contracter en un point axial, tandis que la corolle témoigne d'une nouvelle expansion. Étamines et pistil sont l'expression de la contraction suivante, fruit de la dernière expansion végétale, qui cache en elle la nouvelle graine. C'est un processus d'entéléchie cyclique. Quant aux différences entre le monde animal et le monde humain, la science de l'époque pensait que seuls les animaux possédaient, entre les deux parties symétriques de la mâchoire supérieure, l'os intermaxillaire. Goethe, en 1784, a montré l'inanité de cette thèse. Cela impliquait que les éléments: "répartis chez les animaux, se réunissent en harmonie dans la figure humaine" (p. 35). Goethe l'avait déjà compris dans ses études de physiognomonie, où la structure osseuse du corps humain renvoyait à la position proéminente de la tête, indiquant, d'un point de vue symbolique, le destin spirituel, et non chosal, de l'être humain. Bref, pour Goethe, dans les organismes: "Toutes les qualités sensibles apparaissent [...] comme les conséquences d'un état qui n'est plus perceptible par les sens" (p. 47). Le savant y parvenait grâce à ce que Spinoza avait défini comme une connaissance d'un troisième type, la scientia intuitiva. En effet, rappelle Steiner, le deus sive natura de Spinoza est le contenu idéal du monde, c'est Dieu qui se donne dans les entités, car quelque chose de la physis est vivifié de l'intérieur, par l'idée. Alors que le concept de l'intellect est une somme d'observation et d'analyse, l'idée est le résultat de l'expérience directe et non médiatisée de la raison. Il s'agit là, selon Steiner, d'un idéalisme empirique. Goethe, en dialogue avec les grands noms de l'idéalisme, reconnaît à la pensée la faculté d'aller au-delà du sensible, la capacité de saisir l'idée comme ‘’forme’’ de la nature: "La perception de l'idée dans la réalité est la véritable communion de l'homme " (p. 84). C'est un processus de ‘’cosmisation’’ de l'humain.

Goethe a appliqué cette recherche de l'idée à la multiplicité des perceptions de la couleur. Il a compris que la base de toute couleur est la lumière: les couleurs sont des modifications de la lumière. Ce qui modifiait la lumière en faisant percevoir des couleurs différentes était: "la matière privée de lumière, l'obscurité active [...] Ainsi chaque couleur devenait pour lui la lumière modifiée par l'obscurité" (p. 213). La lumière et les ténèbres sont des idées spirituelles. Goethe, reconnaît Steiner, a indiqué une autre science que la science newtonienne, centrée sur la vision mécaniste. Il s'agit d'une sorte de "physique spéculative" dont, après Schelling et Fechner, peu d'autres ont eu l'intrépidité intellectuelle de renforcer. Face à la dévastation de la nature que le Gestell met en scène, il est peut-être temps de regarder Goethe et sa Naturphilosophie avec plus d'attention.

Giovanni Sessa.

00:18 Publié dans Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, naturphilosophie, goethe, rudolf steiner |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook